Introduction

Calcifying pseudoneoplasm of the neuraxis (CAPNON) was initially reported as a brain calcification by Miller in 1922 and later described as a type of osseous metaplasia by Rhodes and Davis in 1978.Reference Rhodes and Davis1,Reference Miller2 It is hypothesized to be a reactive proliferative process possibly associated with inflammation and/or injury, but its etiology and pathogenesis remain poorly understood.Reference Aiken, Akgun, Tihan, Barbaro and Glastonbury3 CAPNON can occur at any locations of the central nervous system, including the brain and spine, both intra-axial and extra-axial, with only a number of cases reported at the skull base.Reference Aiken, Akgun, Tihan, Barbaro and Glastonbury3–Reference Garcia Duque, Medina Lopez, Ortiz de Mendivil and Diamantopoulos Fernandez6 In these cases, they are commonly mistaken as calcified meningiomas prior to surgical intervention.Reference Aiken, Akgun, Tihan, Barbaro and Glastonbury3,Reference Alshareef, Vargas, Welsh and Kalhorn4,Reference Garen, Powers, King and Perot7–Reference Shrier, Melville and Millet10 Here, we report two CAPNON lesions located at the skull base, and review skull base CAPNONs reported in the literature, with comparisons of CAPNONs and calcified meningiomas.

Case Report

Case 1

History and Examination

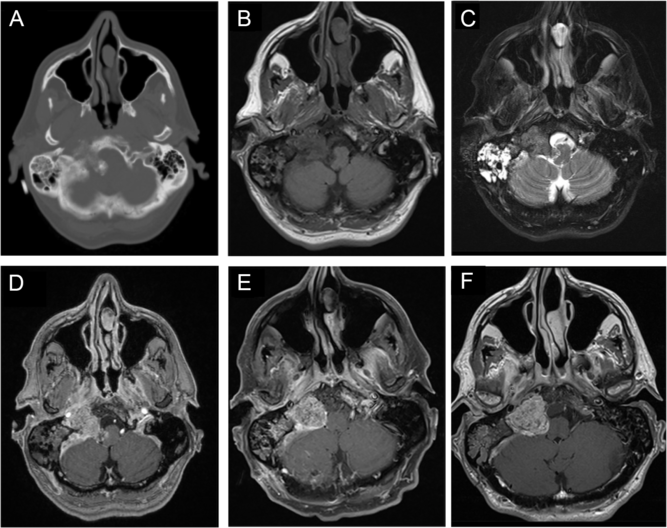

A previously healthy 57-year-old man with a past medical history significant for well-controlled asthma presented with 2 months of hoarseness, dysphagia, and gait imbalance. On physical exam, he had right-sided cranial nerves (CNs) IX, X, XI, XII palsies, as well as gait ataxia. Computed tomography (CT) of the head revealed a heavily calcified lesion within the right cerebellopontine angle (CPA), which seemed to originate from petrous temporal bone and condylar part of occipital bone with secondary involvement of right jugular foramen and hypoglossal canal, causing medulla compression (Figure 1A and B). On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), this lesion was hypointense on T1-weighted images (T1WI; Figure 1B), isointense on T2-weighted images (T2WI; Figure 1C), and avidly enhancing with gadolinium (Figure 1C), without significant vasogenic edema. This was initially thought to be a meningioma, despite the absence of a dural tail. The portion centered in the right jugular foramen measured 3.5 × 2.1 × 2.0 cm (Figure 1B–D). Interestingly, CT and MRI also revealed diffuse right mastoid effusion; however, the patient had no subjective symptoms corresponding to this finding (Figure 1A–C).

Figure 1: Imaging of a right cerebellopontine angle (CPA) calcifying pseudoneoplasm of the neuraxis (CAPNON). Preoperative computed tomography (CT) of the head revealed a heavily calcified lesion within the right CPA involving right jugular foramen and hypoglossal canal, with medullary compression (A); on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), this lesion was hypointense on T1-weighted images (B), isointense on T2-weighted images (C), and avidly enhancing with contrast (D), not associated with significant vasogenic edema. Postoperative MRI demonstrated a CAPNON residual in the jugular foramen, along with improved mass effect on the medulla (E). A 15-month follow-up MRI revealed slight progression in the size of right jugular foramen CAPNON (F).

Operation

We performed a right-sided far-lateral approach for debulking of this lesion with electrophysiological monitoring of somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP), motor evoked potential (MEP), and electromyography of the lower CNs. Multiple areas of confluent calcification were seen within the right CPA. The rootlets of CN XI and XII were identified and preserved. However, we could not identify CN IX and X. Given that the lesion was firm and calcified and that CN XI/XII were adherent to the lesion and CN IX/X were not clearly identified, only the portion of the lesion compressing the medulla was removed to avoid worsening cranial neuropathies. Of note, no reduction in SSEP or MEP occurred during the operation. A postoperative MRI demonstrated a 3.1 × 2.3 × 2.0 cm residual in the jugular foramen, along with improved mass effect on the medulla (Figure 1F).

Pathological Findings

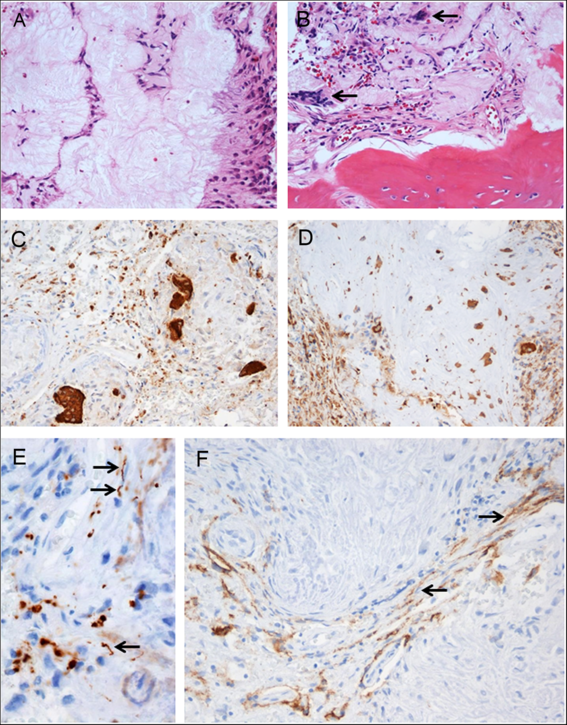

Pathological examination of the resected tissue revealed a fibro-osseous lesion with cores of amorphous to fibrillary materials, peripheral palisading of spindle to epithelioid cells, multifocal calcifications and ossifications, as well as occasional multinucleated giant cells (Figure 2A and B), which was diagnostic of CAPNON. Immunohistochemistry showed focally scattered CD68-positive macrophages including multinucleated giant cells (Figure 2C) and vimentin positivity in most spindle to epithelioid cells (Figure 2D). Neurofilament protein (NFP) immunostaining demonstrated focally positive axons at the periphery of this lesion, suggestive of CN involvement and correlating with the clinical findings of cranial neuropathies (Figure 2E). The lesion exhibited limited epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) positivity in cells or membranes at the periphery of amorphous core (Figure 2F).

Figure 2: Photomicrographs of the right cerebellopontine angle calcifying pseudoneoplasm of the neuraxis. The lesion contained cores of granular amorphous to fibrillary materials with peripheral palisading spindle to epithelioid cells (A), calcification/ossification, and occasional multinucleated giant cells (B, arrows). Immunohistochemistry revealed focally scattered CD68-positive macrophages including multinucleated giant cells (C), vimentin+ in most spindle to epithelioid cells (D), peripherally located NFP+ axons (E, arrows pointing longitudinally sectioned axons; transversely sectioned axons shown as positive dots), and limited EMA+ cells or membranes at the periphery of amorphous core (F, arrows pointing the membranes). Original magnification, ×200 (A–D, F), and ×400 (E).

Postoperative Course

Postoperatively, the patient showed significant improvement in his ataxia, but his cranial neuropathies persisted. At 15-months postoperatively, there was radiographic progression of the disease, with the residual lesion measuring 3.2 × 2.5 × 2.1 cm around the right jugular foramen (Figure 1G). However, the patient remained independent and well clinically.

Case 2

This case was previously reported by Kocovski et al.Reference Kocovski, Parasu, Provias and Popovic11 in our institution – here it is revisited with detailed history, perioperative information, additional pathological examination, and long-term follow-up.

History and Examination

A 70-year-old man was referred to neurosurgery clinic with 4 years of progressive headache, gait difficulty with falls, confusion, and mood changes. His past medical history was significant for medication-controlled seizures secondary to remote encephalitis caused by West Niles virus, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea. His physical examination revealed no focal neurological deficits except a short stride length in his gait. He scored 23/30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment.Reference Nasreddine, Phillips and Bédirian12

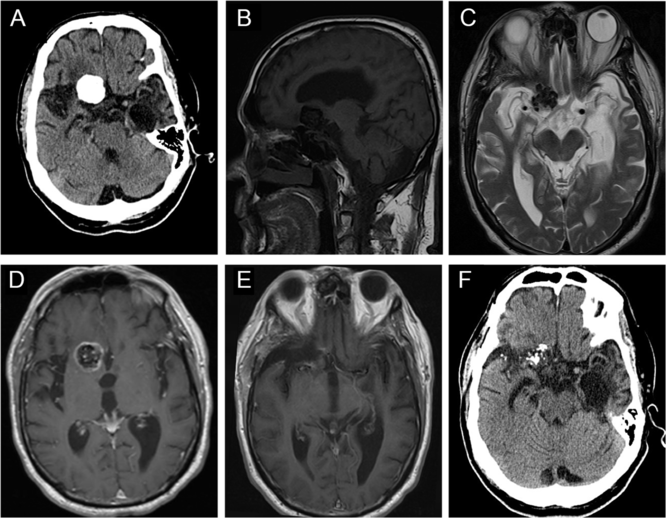

CT of the head revealed a well-circumscribed heavily calcified mass, measuring 2.4 × 2.6 × 1.8 cm, centered within the right basal frontal lobe, with moderate perilesional vasogenic edema (Figure 3A). On MRI, this mass was hypointense on both T1WI and T2WI, with patchy central T2 hyperintensity, and peripheral enhancement (Figure 3B–D), with no evidence of a dural tail. The lesion was in close proximity to the right internal carotid artery (ICA), proximal middle cerebral artery (MCA), and anterior cerebral artery (ACA) (Figure 3D). It was also mildly displacing the prechiasmic segment of the right optic nerve (Figure 3C). There was encephalomalacia within the anterior left temporal lobe with associated ex vacuo dilatation of the temporal horn, which may be a consequence of his previous encephalitis (Figure 3A and C).

Figure 3: Imaging of a right basal frontal calcifying pseudoneoplasm of the neuraxis. (A) Preoperative axial computed tomography (CT) revealed a 2.4 × 2.6 × 1.8 cm well-circumscribed, lobulated, densely calcified lesion centered within the anterior skull base, with some perilesional vasogenic edema. (B) This lesion was hypointense on sagittal T1WI. (C) Axial T2WI demonstrated that the lesion was hypointense with patchy central hyperintensity, and causing some displacement of right optic nerve. (D) The mass demonstrated peripheral contrast enhancement and was in close proximity to the right anterior cerebral artery. (E) Postoperative magnetic resonance imaging showed near-total resection of the lesion. (F) Follow-up CT scan showed no progression of the residual disease after 7 years.

Operation

Given his progressive cognitive decline, surgical resection was recommended. The patient underwent a frontotemporal craniotomy, and the lesion was visualized upon frontal and temporal lobe retraction after sylvian fissure splitting. It was firm, heavily calcified, and could not be mobilized. The lesion was removed in a piecemeal fashion, with the help of the Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator (Integra, bone tip). Rhoton dissectors were used to dissect the right ICA, proximal MCA and ACA, as well as the right optic nerve off the lesion. We left a small amount of residual on the right optic nerve due to difficulty dissecting the lesion off the nerve.

Pathological Findings

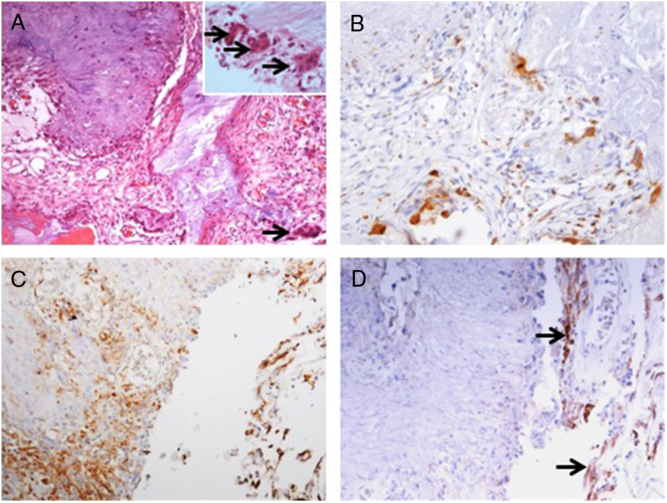

Pathology examination confirmed the lesion to be a CAPNON, with cores of granular amorphous materials and peripheral palisading spindle to epithelioid cells, calcification/ossification, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4A). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated focally scattered CD68-positive macrophages (Figure 4B), focally positive vimentin in spindle to epithelioid cells (Figure 4C), and limited EMA positivity only in the cells or membranes at the periphery of amorphous core (Figure 4D).

Figure 4: Photomicrographs of the right basal frontal calcifying pseudoneoplasm of the neuraxis. The skull base lesion consisted of cores of granular amorphous materials with peripheral palisading spindle to epithelioid cells, calcification/ossification, and multinucleated giant cells (A, arrows including three in an inset with higher magnification). Immunohistochemistry revealed focally scattered CD68+ macrophages (B), vimentin+ focally in spindle to epithelioid cells (C), and limited EMA+ cells or membranes at periphery of the lesion (D, same area as C; arrows pointing the membranes). Original magnification, ×200 (A–D).

Postoperative Course

Postoperative imaging confirmed a near-total resection of this right basal frontal CAPNON (Figure 3E). On postoperative examination, the patient’s headache improved, and he did not sustain any new focal neurological deficits. However, he continued to have progressive global neurological decline including gait difficulty and cognitive decline and required a nursing home placement 6 months after the surgical intervention. It is possible that he had an undiagnosed neurodegenerative condition. He remained stable without focal neurological deficits or radiographic evidence of disease progression 7 years later (Figure 3F) when he underwent a head CT due to a ground-level fall.

Literature Review

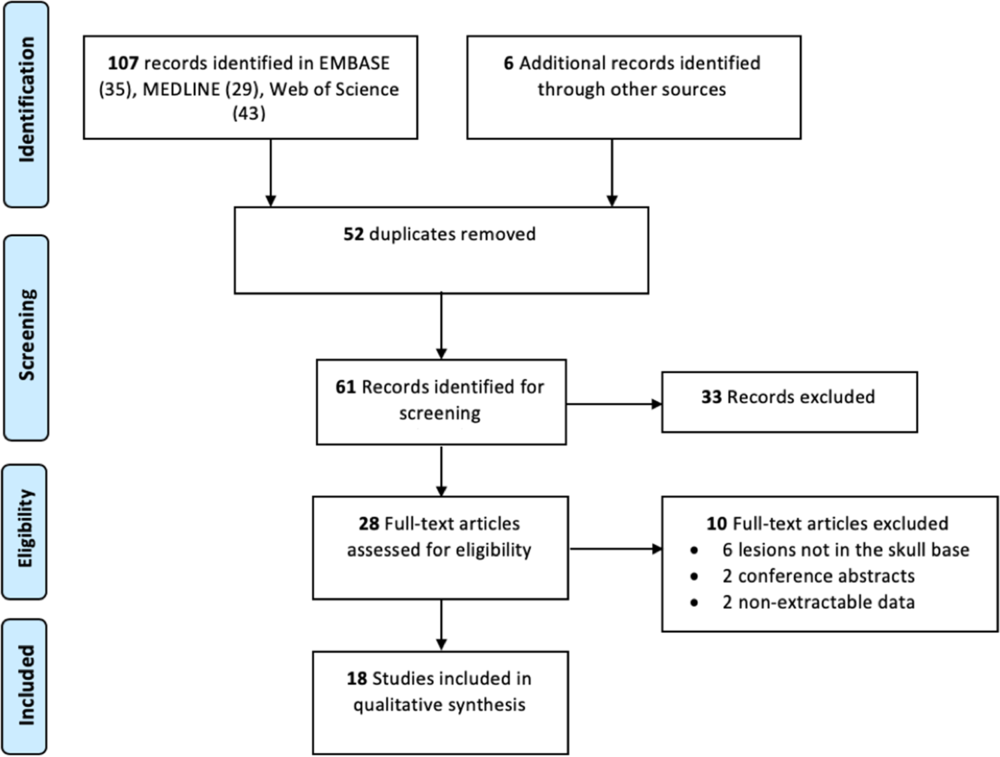

A systematic review of the literature was conducted on skull base CAPNONs. MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) were searched from the inception of the database until June 2019. This systematic review is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Search terms included keyword such as “CAPNON” and combinations of the following words: “calcified,” “pseudo-neoplasm,” “pseudoneoplasm,” “pseudo-tumor,” “pseudotumor,” “neuro-axis,” and “neuraxis.” Screening of searched titles, abstracts, and full texts was done independently by two reviewers, and any discrepancies that occurred during the title and abstract screening stages were resolved by automatic inclusion to ensure that all relevant publications were not missed.

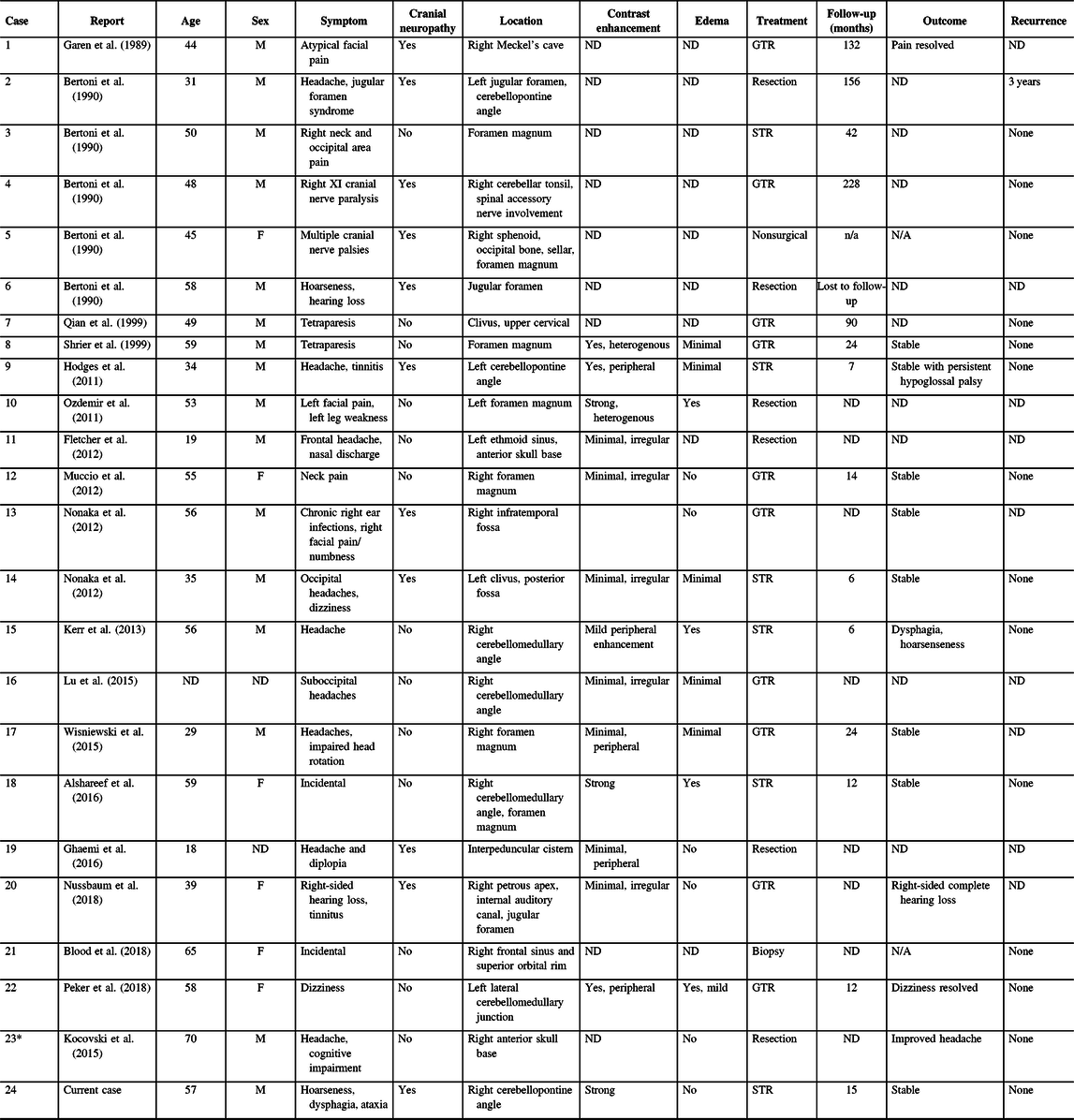

Our literature search identified 113 potentially relevant records. After abstract and full-text screening, 18 records were identified including 23 unique cases of skull base CAPNONs (Figure 5, Table 1).Reference Alshareef, Vargas, Welsh and Kalhorn4,Reference Garen, Powers, King and Perot7–Reference Kocovski, Parasu, Provias and Popovic11,Reference Bertoni, Unni, Dahlin, Beabout and Onofrio13–Reference Wisniewski, Janczar, Tybor, Papierz and Jaskolski24 All 24 patients (including our previously unpublished case) were symptomatic, with 11 (45.8%) patients presenting with cranial neuropathies (Table 1).Reference Garen, Powers, King and Perot7–Reference Nonaka, Aliabadi, Friedman, Odere and Fukushima9,Reference Bertoni, Unni, Dahlin, Beabout and Onofrio13,Reference Hodges, Karikari and Nimjee16,Reference Nussbaum, Hilton and Defillo20 One patient (Case 5) was managed conservatively,Reference Bertoni, Unni, Dahlin, Beabout and Onofrio13 and one patient (Case 22) underwent a biopsy of the lesion,Reference Blood, Rodriguez, Nolan, Ramanathan and Desai14 while the rest underwent resection of the lesion. Analysis of patients with documented extents of resection revealed that 10 patients underwent gross total resection and 6 underwent subtotal resection of CAPNONs. Among all 24 patients, only 2 patients (Cases 1 and 23) had complete resolution of the symptoms postoperatively,Reference Garen, Powers, King and Perot7,Reference Peker, Aydin and Baskaya22 while most patients remained stable.

Figure 5: Preferred Reporting Items in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram outlining the search strategy results from initial search to included studies.

Table 1: Skull base CAPNONs reported in the literature

CAPNON = calcifying pseudoneoplasm of neuraxis; F = female; GTR = gross total resection; M = male; STR = subtotal resection; ND = not documented.

* Case 23 was previously published in our center and reanalyzed in the present study.

Among 11 patients with cranial neuropathies, the outcomes of cranial neuropathies were documented in 6 patients.Reference Garen, Powers, King and Perot7,Reference Nonaka, Aliabadi, Friedman, Odere and Fukushima9,Reference Hodges, Karikari and Nimjee16,Reference Nussbaum, Hilton and Defillo20 Two patients had a sacrifice of the CN function with surgical approaches (Cases 1 and 21),Reference Garen, Powers, King and Perot7,Reference Nussbaum, Hilton and Defillo20 while the remaining four patients (Cases 9, 13, 14, and 24) remained stable with persistent cranial neuropathies.Reference Nonaka, Aliabadi, Friedman, Odere and Fukushima9,Reference Hodges, Karikari and Nimjee16 Another patient (Case 15) had new CN X palsy postoperatively, which was responsive to medical management.Reference Kerr, Borys, Bobinski and Shahlaie17 Jugular foramen CAPNONs were reported in three other cases, of which two cases were not followed clinically (Cases 6 and 21).Reference Bertoni, Unni, Dahlin, Beabout and Onofrio13,Reference Nussbaum, Hilton and Defillo20 The third patient (Case 2) initially underwent an intralesional excision and had disease progression at 3 years requiring repeat surgical intervention.Reference Bertoni, Unni, Dahlin, Beabout and Onofrio13 Notably, this was the only reported case of CAPNON recurrence in the series of 24 patients.

Discussion

Since the first characterization of CAPNON as an osseo-fibrous lesion in 1978, over 100 cases of CAPNON have been reported. The average age at presentation is 47 years and a slight male predilection is seen.Reference Barber, Low, Johns, Rich, MacDonald and Jones5 With regard to spinal CAPNONs, they are typically located in the epidural space (81.48%).Reference Garcia Duque, Medina Lopez, Ortiz de Mendivil and Diamantopoulos Fernandez6 In contrast, intracranial CAPNONs are more commonly found intra-axially.Reference Alshareef, Vargas, Welsh and Kalhorn4–Reference Garcia Duque, Medina Lopez, Ortiz de Mendivil and Diamantopoulos Fernandez6 In this study, we reviewed a total of 24 cases located at the skull base and discovered a high incidence (45.8%) of cranial neuropathies associated with skull base CAPNONs. In our case report of a right CPA CAPNON, we present novel pathological findings of the CN involvement with NFP-positive entrapped nerve fibers/axons identified at the periphery of the lesion, correlating with clinical cranial neuropathy.

The etiology of CAPNON remains unclear, but a reactive process is favored for its pathogenesis. Our first case was a right-sided CPA CAPNON which occurred in a patient with right-sided mastoid effusion. Our second case was a right basal frontal CAPNON in a patient who had remote encephalitis caused by West Nile Virus, with the CAPNON adjacent to the areas of encephalomalacia caused by the previous neurological insult. Both of these cases of CAPNONs occurred in the close vicinity to a separate, and possibly preceding infectious/inflammatory process, further supporting the notion that CAPNON is a reactive proliferative process associated with inflammation and/or injury.Reference Aiken, Akgun, Tihan, Barbaro and Glastonbury3 In reviewing other published cases of skull base CAPNONs, we found that past medical history was not available in the majority. However, Nonaka et al. published a case of a right-sided infratemporal CAPNON in which their patient presented with chronic right-sided ear infections (Table 1).Reference Nonaka, Aliabadi, Friedman, Odere and Fukushima9 While it cannot be concluded that the ear infections preceded the CAPNON, its close vicinity suggests they may be related.

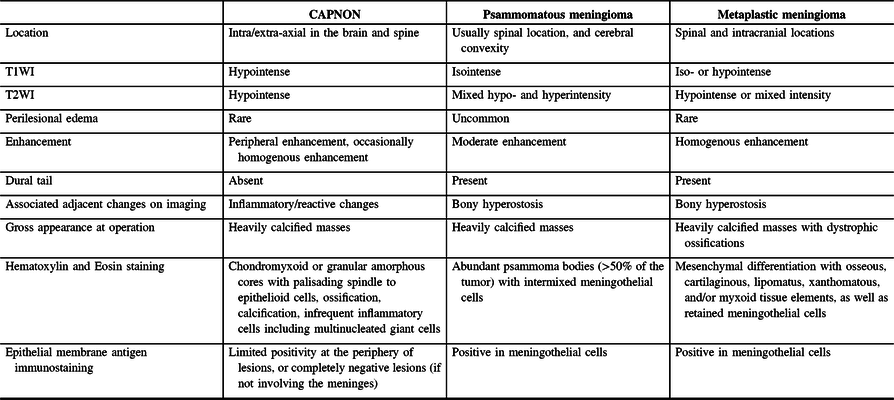

Radiographic differential diagnoses of skull base CAPNONs should include calcified meningioma subtypes, chordoma, chondrosarcoma, schwannoma, granulomatous lesions, and other inflammatory lesions.Reference Bertoni, Unni, Dahlin, Beabout and Onofrio13 The meningioma subtypes, in particular psammomatous and metaplastic meningiomas, should be the top differential diagnoses for a calcified lesion located at the skull base. CAPNONs are often mistaken as calcified meningiomas until a pathological diagnosis is made after surgical intervention.Reference Aiken, Akgun, Tihan, Barbaro and Glastonbury3,Reference Alshareef, Vargas, Welsh and Kalhorn4,Reference Garen, Powers, King and Perot7–Reference Shrier, Melville and Millet10 However, there are some subtle differences in the imaging characteristics between CAPNONs and calcified meningiomas (Table 2). First, the lack of a dural tail on CAPNONs can help distinguish them from calcified meningiomas. Second, CAPNONs are usually hypointense on T1WI and T2WI and perilesional edema is rare.Reference Aiken, Akgun, Tihan, Barbaro and Glastonbury3,Reference Barber, Low, Johns, Rich, MacDonald and Jones5 Additionally, the majority of cases of CAPNON demonstrate a peripheral enhancement pattern in contrast to psammomatous and metaplastic meningiomas.Reference Barber, Low, Johns, Rich, MacDonald and Jones5 Of note, our right CPA CAPNON is vividly enhancing with contrast, similar to a previous case reported by Alshareef and colleagues.Reference Alshareef, Vargas, Welsh and Kalhorn4 In contrast, psammomatous meningiomas are often isointense on T1WI and have mixed hypo- and hyperintensity on T2WI, with moderate homogeneous enhancement with contrast. Similar to CAPNONs, perilesional edema is uncommon. Additionally, psammomatous meningiomas have a predilection for the spine and cerebral convexity.Reference Liu, Lu and Peng25 Metaplastic meningiomas tend to be iso- or hypointense on T1WI, hypointense or of mixed intensity on T2WI, with homogenous enhancement and rare perilesional edema.Reference Caffo, Caruso, Barresi and Tomasello26,Reference Tang, Sun and Chen27

Table 2: Comparisons of CAPNON, psammomatous meningioma, and metaplastic meningioma

Pathologically, CAPNONs are distinctly different from grossly calcified, psammomatous meningiomas and metaplastic meningiomas. CAPNON is typically composed of the following components: (1) chondromyxoid cores containing amorphous to fibrillary materials; (2) peripheral palisading of spindle to epithelioid cells; (3) calcifications and ossifications; and (4) foreign-body reaction with multinucleated giant cells.Reference Qian, Rubio and Powers23 Despite high variations in these morphological components, the chondromyxoid cores with calcification seem to be a principal constituent of CAPNON. On the other hand, psammomatous meningiomas consist of abundant psammoma bodies (more than half of the tumor) with intermixed meningothelial cells.Reference Liu, Lu and Peng25 Metaplastic meningiomas are characterized by mesenchymal differentiation including osseous, cartilaginous, lipomatus, xanthomatous, and/or myxoid tissue elements, with retained meningothelial cells in nonmetaplastic areas.Reference Caffo, Caruso, Barresi and Tomasello26,Reference Tang, Sun and Chen27 EMA immunostaining, a routinely used marker for meningiomas, is positive largely in the retained meningothelial cells in metaplastic and psammomatous meningiomas. In contrast, CAPNONs have limited EMA positivity that is often linear in distribution and typically seen at the periphery of the amorphous cores or the tissue edge of CAPNONs,Reference Aiken, Akgun, Tihan, Barbaro and Glastonbury3 which may be reflective of the meningeal involvement in the stroma rather than the constituent of CAPNONs. In the 24 reviewed cases of skull base CAPNONs, EMA immunostaining was positive with or without specified distribution in 6 cases (including our 2 cases),Reference Blood, Rodriguez, Nolan, Ramanathan and Desai14,Reference Fletcher, Greenlee, Chang, Smoker, Kirby and O’Brien15,Reference Kerr, Borys, Bobinski and Shahlaie17,Reference Wisniewski, Janczar, Tybor, Papierz and Jaskolski24 but negative in 2 cases,Reference Hodges, Karikari and Nimjee16,Reference Nussbaum, Hilton and Defillo20 and not mentioned in the remaining 16 cases. We speculate that EMA is usually negative in CAPNONs without the meningeal involvement or focally positive in CAPNONs with the meningeal involvement, and its positivity is limited to the meningothelial cells entrapped in CAPNON lesions. Therefore, EMA is a useful pathological marker to differentiate CAPNONs from calcified psammomatous or metaplastic meningiomas (Table 2).

The morbidity associated with CAPNONs arises primarily from mass effect. Intracranial CAPNONs can cause seizures, headaches, vision loss, weakness, pain, and developmental delay.Reference Kerr, Borys, Bobinski and Shahlaie17 Additionally, our systematic review of the literature found that CAPNONs at the skull base are associated with a high incidence of cranial neuropathies (45.8%). This may be partially explained by mass effect exerted on CNs by the lesion around the narrow neural foramina. It could also be related to the inflammatory nature of CAPNON. As illustrated in our right CPA CAPNON case, nerve axons have been at the periphery of the lesion, which may reflect inflammatory “invasion” of the nerves and explain the high incidence of cranial neuropathies.

The previously reported cases have described a 4- to 17-year monitoring period before progression warranting neurosurgical intervention.Reference Barber, Low, Johns, Rich, MacDonald and Jones5 Due to the indolent nature of CAPNONs, very few patients with recurrences have been documented in the literature. In the 24 reviewed cases, only one case of a jugular foramen CAPNON recurred at 3 years requiring repeat operation.Reference Bertoni, Unni, Dahlin, Beabout and Onofrio13

Conclusion

CAPNONs located at the skull base can mimic calcified meningiomas and is associated with a high incidence of cranial neuropathy. When considering surgical intervention, surgeons should be aware that gross total resection and CN detachment from CAPNON may be difficult, due to anatomical location of the lesion, associated technical challenge, and possible inflammatory involvement of CNs.

Statement of Authorship

KY, JQL, and KR designed the study. KR, BHW, MNB, and JQL provided patient data and analysis. KY and YE extracted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.