Introduction

While many rapid eye movement (REM) sleep parasomnias have been described, a vast majority comprise the REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), which is largely an illness seen among elderly males. Reference Avidan and Kaplish1 The clinical significance of RBD is now well established, not only for its medicolegal implications due to the violent nature of the abnormal movements during sleep but also mainly for the progression in more than 80% of patients with RBD to a neurodegenerative disorder, mostly synucleinopathies. Reference Schenck, Boeve and Mahowald2 Over the past decades, a number of case reports have also described many conditions, which can have RBD as a manifestation of underlying neurological illness, for example, narcolepsy, brainstem lesions, encephalitis, autism, and others. Reference De Barros-Ferreira, Chodkiewicz, Lairy and Salzarulo3–Reference Thirumalai, Shubin and Robinson8 Among these, many patients are younger than the usual age of presentation of the commoner idiopathic RBD which may precede or is co-existent with neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, or multiple system atrophy.

The entity of REM sleep without atonia (RWA) has assumed much clinical importance since it is the essential polysomnographic (PSG) manifestation of RBD. The long-term clinical significance of isolated RWA remains a subject of investigation. Reference McCarter, Louis and Boeve9

The current study aims at evaluating clinical and PSG characteristics of young patients diagnosed to have RBD and to compare their REM sleep features with age-matched healthy controls and with patients suffering from autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and epilepsy.

Methods

This is a retrospective chart review-based study, including young subjects from the Neurology services sleep disorders facility at our center, an apex quaternary-care academic center, over a 2-year study period between 2012 and 2014.

Study Subjects

Consecutive young subjects, who were less than 25 years of age and who underwent video-PSG at our center, formed the study population. These were classified into the following groups:

(i) patients diagnosed with RBD, having been evaluated through the sleep disorders facility for abnormal behaviors during sleep,

(ii) patients with autism spectrum disorder,

(iii) patients with ADHD,

(iv) patients with epilepsy, and

(v) healthy age-matched control subjects

all of whom were in the same age group and underwent video-PSG during the same study period.

Patients with an established video-PSG diagnosis of non-rapid eye movement (NREM) parasomnia and unconscious or otherwise medically serious patients were excluded. Those with no REM period recorded during the PSG night were also excluded.

The “normal controls” were from a group enrolled in another ongoing study on children and adolescents with autism. All of them had been screened for sleep complaints and were asymptomatic for the same.

Video-PSG Procedure

As a routine for all the PSGs, overnight polysomnography (PSG) study had been performed by trained sleep technologists, according to the latest version of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) scoring manual, for all subjects. Reference Berry, Budhiraja and Gottlieb10 The monitored parameters included left and right electrooculogram, extended electroencephalogram (EEG), mental and submental electromyogram (EMG), left and right anterior tibialis EMG, single electrocardiogram waveform, snoring, continuous airflow via thermistor, nasal pressure transducer, chest and abdominal effort, oxygen saturation, and body position, which was also confirmed through video monitoring.

For the patients in group (i), additional EMG channels with electrodes having been placed on the left extensor digitorum and the right deltoid muscles were also recorded. A 16 channel EEG was also obtained as part of the detailed protocol for evaluation of patients with suspected parasomnias.

For patients in group (iv) also, 16 channel EEG had been obtained in addition to the PSG hook-up described above.

Video-PSG Interpretation

Definitions of all PSG parameters as well as specific diagnosis, for example, Obstructive sleep apnea and periodic limb movement disorder, were based on AASM guidelines. Reference Berry, Budhiraja and Gottlieb10

Clinical details of behaviors recorded during REM sleep (and other stages) had been noted and shown to carers, to ascertain habitual nature of the same, in case of patients who had presented to the clinic for abnormal behaviors during sleep.

Specific REM Sleep Analysis

For the purpose of this study, REM epochs of all subjects included were re-scored by two independent scorers (BS and AG). The following parameters were analyzed and tabulated, for each group:

a. total number of REM epochs during PSG night

b. REM percentage of total sleep time

c. Total number of REM epochs with excessive transient muscle activity (ETMA) or sustained muscle activity (SMA)*

d. Percentage of REM epochs with ETMA or SMA

e. Number (%) and percentage of epochs with ≥50% of 10-second mini-epochs with ETMA and/or SMA

f. Number (%) and percentage of epochs with ≥20% of 10-second mini-epochs with ETMA and/or SMA

g. Number (%) subjects in each group with ≥5% of REM epochs showing ETMA and/or SMA in ≥20% of the epoch

* SMA (tonic activity) in REM sleep: An epoch of REM sleep with at least 50% of the duration of the epoch having a chin EMG amplitude greater than the minimum amplitude demonstrated in NREM sleep.

ETMA (phasic activity) in REM sleep: In a 30-second epoch of REM sleep divided into 10 sequential 3-second mini-epochs, at least 5 (50%) of the mini-epochs contain bursts of transient muscle activity. In RBD, ETMA bursts are 0.1–5.0 seconds in duration and at least four times as high in amplitude as the background EMG activity.

Based on AASM manual version 2.3. Reference Berry, Budhiraja and Gottlieb10

Diagnosis of RBD

The diagnosis of RBD was made strictly in accordance with the criteria described in the International Classification for Sleep disorders, version 3, Reference Thorpy11 while RWA (also a requirement for the diagnosis of RBD) was diagnosed in accordance with the AASM guidelines manual version 2.3. Reference Berry, Budhiraja and Gottlieb10

Parameters (f.) and (g.) mentioned under the previous sub-heading were computed for further quantification of the PSG abnormalities observed during REM sleep of included subjects, especially those not fulfilling AASM criteria for RWA.

Results

During the study period, a total of 102 subjects in the specified age group were identified, who had undergone technically adequate polysomnography for at least one night. Among these, 32 had autism spectrum disorder, 10 of whose PSG studies recorded no REM epochs. Hence 22 from this group were included. PSG studies of 18 normal children were available, out of which 4 had no REM sleep recorded. Apart from these, there were 10 PSG studies of children with ADHD and 30 of those with epilepsy, which were analyzed. The rest were those of 12 patients who had presented to the clinic with episodic abnormal behavior during sleep and whose PSG did not identify findings supporting the diagnosis of NREM parasomnia or seizures. Hence, PSG studies of a total of 88 subjects were available for detailed REM sleep analysis.

This was a male-dominant population, with all 12 suspected RBD patients, 16/22 with autism, all 10 ADHD, 19/30 epilepsy patients, and 12/14 normal controls being male. Gender matching was not possible since this is a retrospective study, and it was important to include all consecutive patients in each group. Age range in various groups has been mentioned in Table 1.

Table 1: Age/Sex distribution and REM sleep analysis of young subjects included in various clinical categories

ADHD = attention deficit hyperactive disorder; REM = rapid eye movement; RWA = REM sleep without atonia.

Sustained muscle activity (tonic activity) in REM sleep: An epoch of REM sleep with at least 50% of the duration of the epoch having a chin EMG amplitude greater than the minimum amplitude demonstrated in NREM sleep.

Excessive transient muscle activity (phasic activity) in REM sleep: In a 30-second epoch of REM sleep divided into 10 sequential 3-second mini-epochs, at least 5 (50%) of the mini-epochs contain bursts of transient muscle activity. In RBD, excessive transient muscle activity bursts are 0.1–5.0 seconds in duration and at least four times as high in amplitude as the background EMG activity.

* RWA defined based on AASM scoring manual (2007)Reference Berry, Budhiraja and Gottlieb10 version 2.3 guidelines.

Apart from the 12 patients who had presented with possible parasomnias, no other subjects included had history of abnormal behavior during sleep.

Limited details of imaging obtained for patients in included groups were available at the time of analysis:

Autism – Imaging was done among 19 out of 22 patients, 17 reported normal, 1 showed Ischemic changes in bilateral parietooccipital regions, and 1 had right frontal lobe dysplasia.

ADHD – MRI conducted whenever required clinically, but not as a part of study.

Epilepsy – All patients underwent either MRI or CT scans; nearly half of these were abnormal with focal brain lesions

RBD – Eleven patients underwent MRI/CT Scan. One MRI was reported abnormal – possible diffuse hypoxic ischemic changes over widespread regions bilaterally.

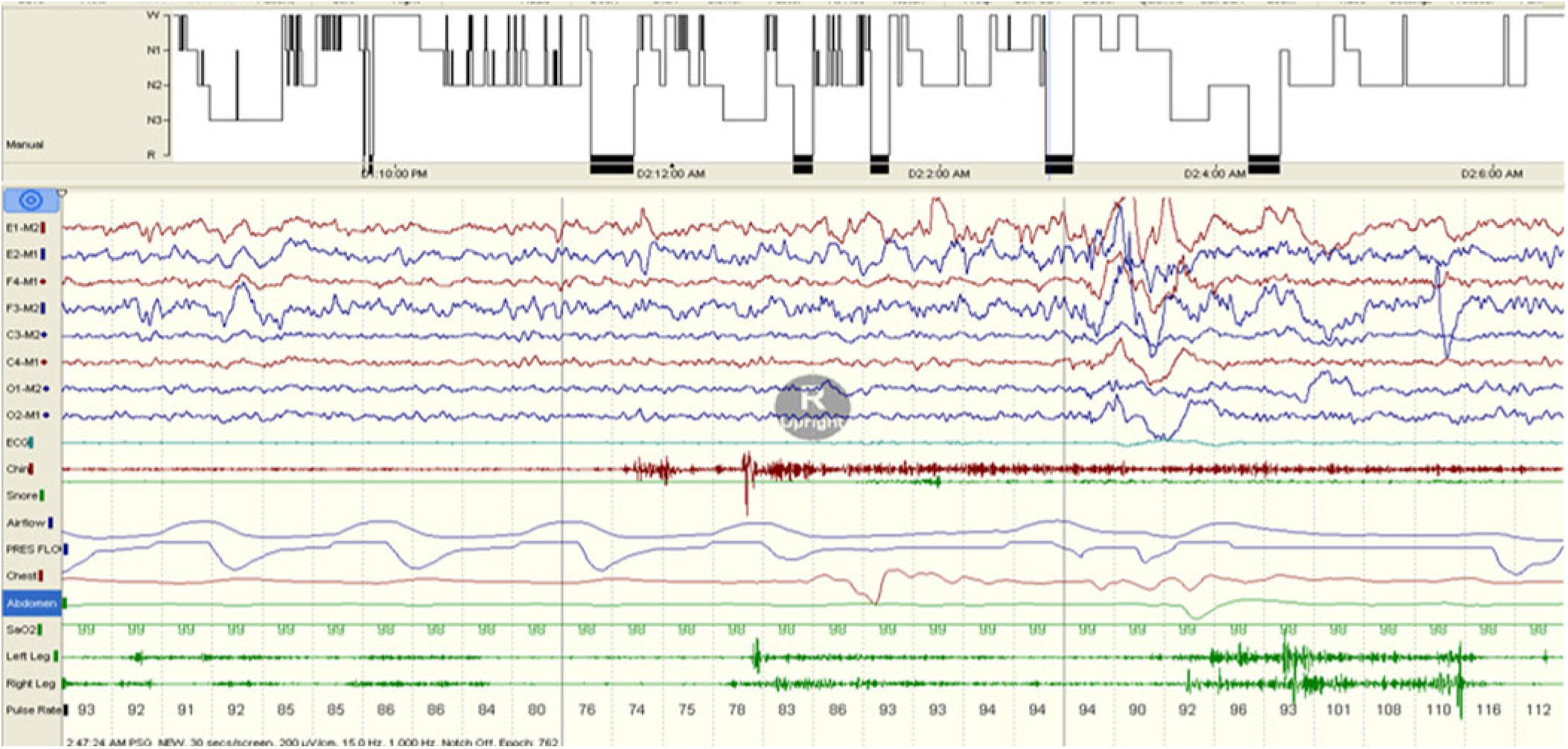

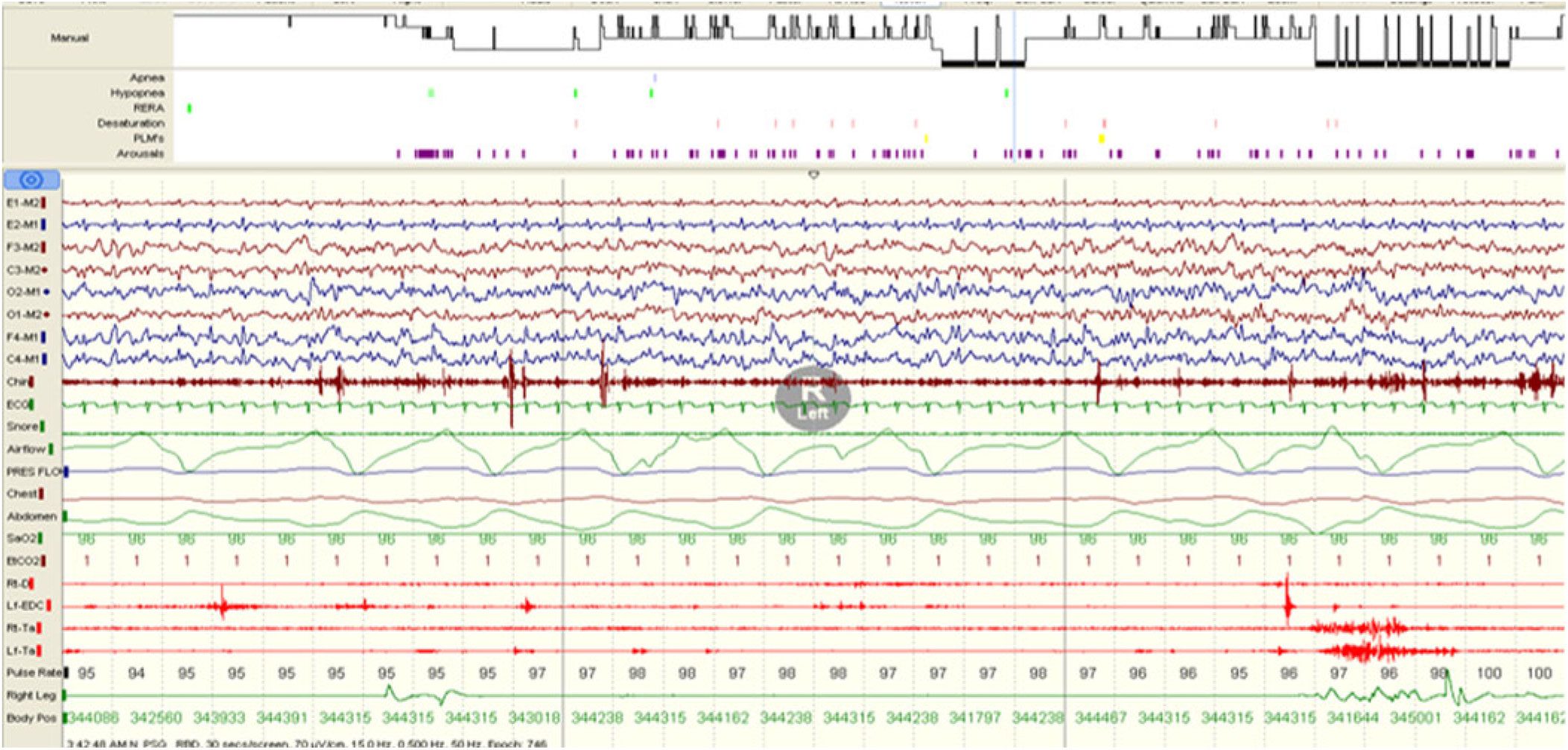

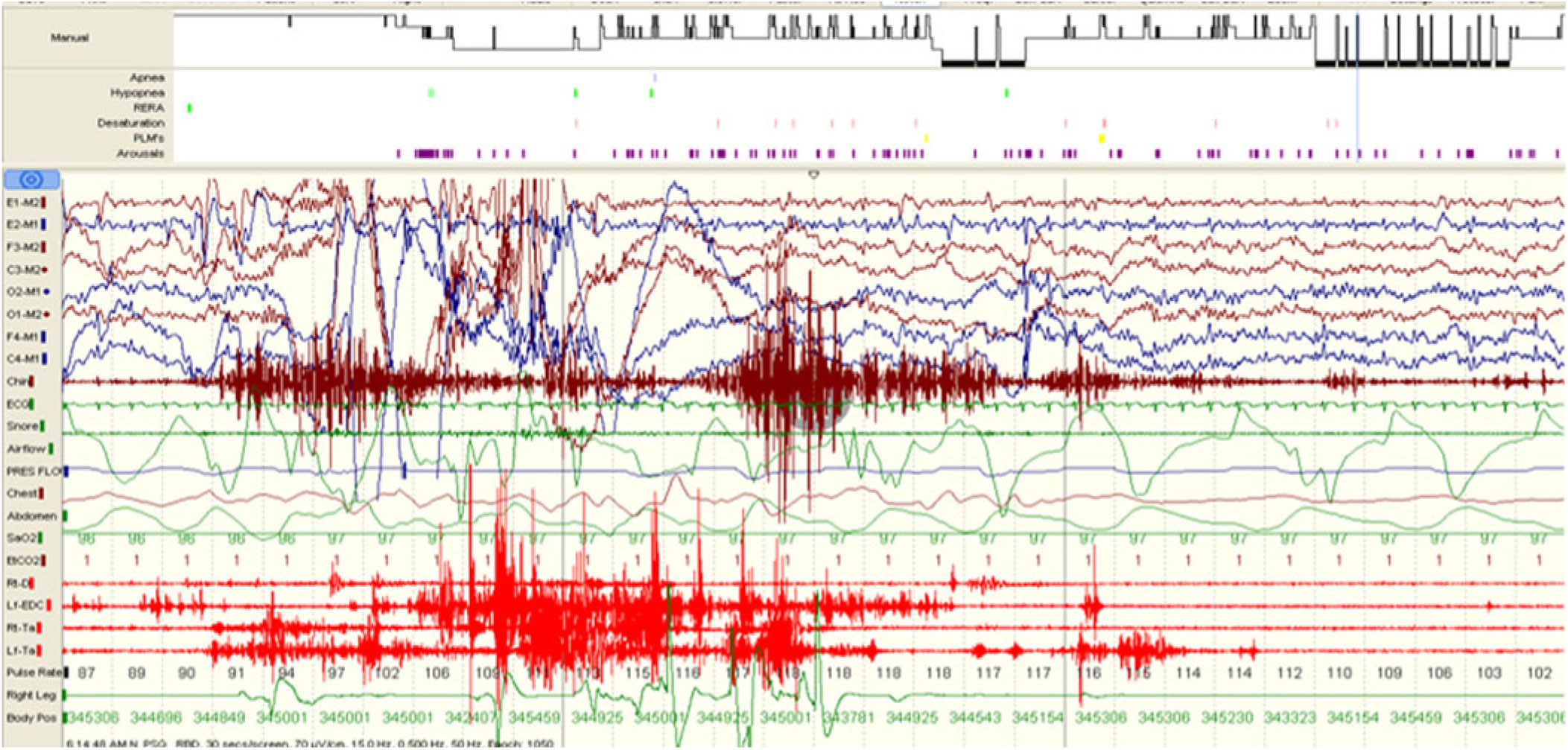

The average number of REM epochs (85.47 ± 70.12) and REM percentage (7.54 ± 5.4) was lowest in the group of patients with autism and highest in clinic patients who had presented with suspected RBD (183 ± 79.23). Expectedly, the latter was also the group with maximum number and percentage of REM epochs with ETMA and/or SMA. ETMA and/or SMA during REM epochs was found in all clinic patients diagnosed with RBD, in 16/22 (72%) autistic patients, 6/10 (60%) ADHD patients compared to only 6/30 (20%) patients with epilepsy, and none of the normal subjects (Table 2) (Figures 1–3).

Table 2: REM characteristics of subjects manifesting RWA

ADHD = attention deficit hyperactive disorder; REM = rapid eye movement; RWA = REM sleep without atonia; ETMA = excessive transient muscle activity; SMA = sustained muscle activity; EMA = excessive muscle activity.

Figure 1: Sustained muscle activity (SMA).

Figure 2: Excessive transient muscle activity (ETMA).

Figure 3: Sustained muscle activity (SMA) and excessive transient muscle activity (ETMA).

On analysis of video on the video-PSG, eight patients among autistic and three among ADHD subjects were observed to have non-specific body movements during REM sleep ranging from sudden jerky movements of limbs or head, rolling of legs, repetitive but not stereotyped movements of upper limbs with occasional crying. One patient in the epilepsy sub-group had non-specific upper limb movements without any concomitant ictal EEG correlates. Details of clinical presentation of patients in the suspected RBD group are listed; details of associated conditions and medication history along with the video-PSG findings for this group are described in Table 3.

Table 3: Clinical presentation, additional clinical details, and video-PSG findings of young patients undergoing video-PSG evaluation for suspected RBD and with a final diagnosis of RBD (N = 12)

AHI = apnea hypopnea index, EDS = excessive daytime sleepiness, GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disorder, NDD = neurodevelopmental disorder, OCD = obsessive compulsive disorder, RLS = restless legs syndrome, RMD = rhythmic movement disorder, TTH = tension type headache.

All patients diagnosed with RBD were treated with 0.125–0.25 mg of nightly Clonazepam and at a mean follow-up of 6 ± 5.66 months; they were all free from symptoms of the nocturnal events. Apart from oral Clonazepam, one patient who was on multiple narcotic drugs underwent successful de-addiction over a period of 4 months, two patients who were receiving selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medications tapered the same off, while the two patients who were diagnosed to have narcolepsy continued to remain on the tricyclic anti-depressant (TCA) medication which had been prescribed to them.

Medications used in different groups studied were as follows:

ADHD: Atomoxetine, Methylphenidate, and Sodium valproate

Autism: Risperidone, Olanzapine, Atomoxetine, Sodium valproate, Carbamazepine, and Levetiracetam

Epilepsy: Oxcarbazepine, Carbamazepine, Levetiracetam, Sodium valproate, Lacosamide, and Clobazam.

Patients in all groups, who did not demonstrate RWA, were also on the same group of medications. It is noteworthy that, apart from SSRI/TCA use in four patients detailed above, no other medications used by patients in different groups are known to affect muscle tone in REM sleep, except for potential for some anti-psychotic medications used for patients with autism.

Discussion

This is the largest study reporting REM sleep characteristics of young subjects with RBD, as well as those with other neurological disorders. While quantitative analysis of the REM periods of the young patients suffering from RBD is presented, the main observations made are of a large proportion of PSG studies of patients diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders and those with ADHD also show loss of normal REM-associated atonia during nearly 10% of the REM epochs recorded. This compares with no similar findings among normal age-matched subjects and a small percentage of patients with epilepsy.

RBD among children, adolescents, and young adults has been reported only in small case series and is evidently an uncommon clinical problem. Lloyd et al. reported a series of 15 patients younger than 18 years of age, with RBD, 2 of which had only RWA. The associated co-morbidities and response to treatment were similar to our observations, in the group of RBD patients reported. Reference Lloyd, Tippmann-Peikert, Slocumb and Kotagal12 Another series of 22 patients younger than 40 years age also reported similar clinical and PSG findings. Reference Song and Joo13 Apart from these a number of case reports have been published and co-morbidities ranging from brainstem tumors to juvenile Parkinson’s disease have been observed with young RBD (Table 4). The interesting and novel part of our study is the observation of RWA and motor behaviors recorded during REM sleep of children with autism, ADHD, and some children with epilepsy, which may not necessarily give the appearance of dream enactment as often and as clearly as in adults. Reference Nevsimalova, Prihodova, Kemlink, Lin and Mignot6,Reference Sheldon and Jacobsen14–Reference Turner and Allen18,Reference Ross, Ball and Dinges20 History of episodic abnormal behaviors during sleep was not reported for any subjects apart from the group which presented with suspected parasomnia. This can be attributable to the often non-specific and non-stereotyped characteristics of behaviors and abnormal movements observed on video among patients included. Many abnormal behaviors are commonly observed among patients with autism spectrum disorders, and it is possible that caregivers would be unable to differentiate between behaviors observed during wakefulness versus those in sleep. Hancock et al. studied RWA quantification in children with RBD and a control group without RBD and found significantly greater amounts of RWA among the former. Reference Hancock, St Louis and McCarter19

Table 4: Review of published Case reports and series of RBD and RWA in young

We categorized RWA features in greater detail than required per the AASM guidelines for RWA among adults. Apart from the requirement by AASM guidelines for greater than 50% of 10 three-second mini-epochs for labeling any particular epoch to show ETMA or SMA, various cut-off percentages for individual muscles and muscle combinations showing RWA have been identified, for the diagnosis of RBD, in previous studies. These authors found that for clinical purposes, a cut-off of 18.2% of “any,” that is, tonic or phasic or both EMG activity in the mentalis muscle was sufficient for diagnosis of RBD. Reference Frauscher, Iranzo and Gaig21 We have reported our analysis by both, this less stringent cut-off as well as that of 50%, for the epochs showing increased muscle tone during REM sleep. Some other authors reporting EMG quantification among patients with RBD have also aimed at identifying cut-off values to label abnormal muscle tone during REM sleep indicative of a diagnosis of RBD. Reference Consens, Chervin and Koeppe22 Postuma et al. suggest that the amount of RWA appears to predict the development of PD, showing that idiopathic RBD patients who developed PD had baseline abnormal tonic chin muscle activity of 73% compared to 41% of those who remained disease free. They also reported high RWA rates (54%) among those suffering from Lewy body dementia. Reference Postuma, Gagnon, Rompré and Montplaisir23 Nevertheless, it is important to note that such quantification and cut-off rates for RWA, as well as values correlative with clinical RBD are currently unavailable, for younger patients presenting with RBD or those whose PSG shows only RWA. Our study is important in gathering information required to establish clinical significance of the unusual PSG findings among various young populations studied by us.

The finding of prominent RWA among young patients with various disorders studied by us, notably autism as well as ADHD, has not been reported before. The clinical and, especially, the prognostic implications should be of considerable interest and should encourage future research in this area. An observation of prognostic concern from recent studies is the higher prevalence of Parkinson’s disease than normal age-matched population, among adults with autism. Reference Starkstein, Gellar, Parlier, Payne and Piven24,Reference Croen, Zerbo and Qian25 In addition, mutations in the Parkinson’s disease-associated, G-Protein-coupled receptor 37 (GPR37) gene, which is associated with the dopamine transporter, have been identified in some patients with the autism spectrum disorder and proposed to be related to the deleterious effects of the autism spectrum disorders. Reference Fujita-Jimbo, Yu and Li26 Such genetic associations among Parkinsonism with ADHD and autism have also been a matter of intensive exploration and may be of relevance to patients with autism and ADHD with RWA/RBD. Reference Jarick, Volckmar and Pütter27–Reference Yin, Chen and Li29

While this is the first large study on RWA and RBD in children, adolescents, and young adults, its limitations are the small numbers in each group and non-availability of adequate follow-up data for most of these.

Conclusion

We observed that a large percentage of young patients with autism and ADHD and some with epilepsy demonstrate loss of REM-associated atonia and some RBD-like behaviors on polysomnography similar to young patients presenting with RBD. The clinical significance of this finding thus forms an interesting subject of future research.

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful for the help in data entry and secretarial assistance provided by Jyoti Katoch, Tukaram Iyer and for the data acquisition carried out by sleep technologists Bharat Singh, Nikhil Kumar, and Rahul Rawat. We also acknowledge and deeply appreciate the help received from Dr. Carlos H. Schenck, with his valuable comments and suggestions toward improvement of this manuscript.

Statement of Authorship

GS - conceptualization, manuscript writing. AG - polysomnography analysis and interpretation, data analysis, manuscript writing. KC - data collection for epilepsy patients. AR - clinical data collection for patients with autism spectrum disorder and normal controls, analysis of data for these groups. AAJ - clinical data collection and analysis for patients with ADHD. MM - study planning and supervision of ADHD data management. SG - supervision of autism data collection. MK - supervision of autism data analysis and interpretation. MA - data collation, manuscript editing. SP - data collation.

Disclosure

None of the authors have any financial support or conflicts of interest to disclose.