Introduction

Functional movement disorders (FMDs) pose significant diagnostic and management challenges for the neurologist.Reference Morgante, Edwards and Espay1 These disorders (FMDs) are well characterized in adults, but childhood-onset FMDs have not been extensively studied.Reference Ferrara and Jankovic2 FMDs are also more common in adults and uncommon or rare in children.Reference Kamble, Prashantha and Jha3,Reference Stone, Wojcik and Durrance4 FMDs account for about 1.5% of all the patients attending neurology clinics and 17% of all functional neurological disorders.Reference Factor, Podskalny and Molho5 In the movement disorders clinic, the estimated prevalence is about 2%–10%.Reference Edwards and Bhatia6 About 10% of them are found to have associated organic disorder.Reference Hallett7 However, the exact prevalence is difficult to estimate due to the case definition, referral bias, difficulty in differentiating from the organic disorders, and low index of suspicion by the treating physician.

These disorders do not have any structural or biochemical abnormality, but are believed to be due to underlying psychological or psychiatric illness.Reference Czarnecki and Hallett8,Reference Gupta and Lang9 They are thus a part of functional neurological disorders. In recent years, there are controversies regarding the terminologies “psychogenic” or “functional” for these disorders.Reference Dallocchio, Marangi and Tinazzi10 The diagnostic criteria were initially laid by Fahn and WilliamsReference Fahn and Williams11 in patients with psychogenic dystonia that was later modified to include other FMDs.Reference Gupta and Lang9,Reference Fahn and Williams11

Given the paucity of literature on these disorders in children, the study of these disorders in children becomes essential as it affects the mental and social well-being of the child. In addition, it is associated with school absenteeism, poor scholastic performance, lack of self-confidence, and parental anxiety. Hence, we aimed to study the socioeconomic and cultural factors, underlying psychopathology and the phenomenology of FMDs in children.

Methods

The present study was a retrospective chart review of 39 children (aged ≤ 18 years) who attended our neurology OPD and the movement disorders clinic between January 2011 and May 2020. Among them, the clinical profile of 22 children has been published earlier.Reference Kamble, Prashantha and Jha3 The study was approved by the institute’s ethics committee. The diagnosis of FMD was based on the criteria described by Fahn and Williams and Gupta and Lang.Reference Gupta and Lang9,Reference Fahn and Williams11 All these children were examined by the senior movement disorder specialist (PKP and RY) with clinical opinion from the child psychiatrist (SS). All the relevant demographic data including the ethnicity, socioeconomic and cultural background were documented. Detailed history, examination findings, electrophysiological, and other investigations were also noted. The clinical videos were also reviewed. Most of these children had undergone electrophysiological evaluations such as surface electromyogram (EMG), long-loop reflexes, jerk-locked back averaging, and Bereitschaftspotential (BP) depending on the underlying phenomenology. The psychiatric notes were also reviewed and discussed with the child psychiatrist (SS). The treatment details and the outcome were also recorded.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using the R software. All the variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, percentage, and range.

Results

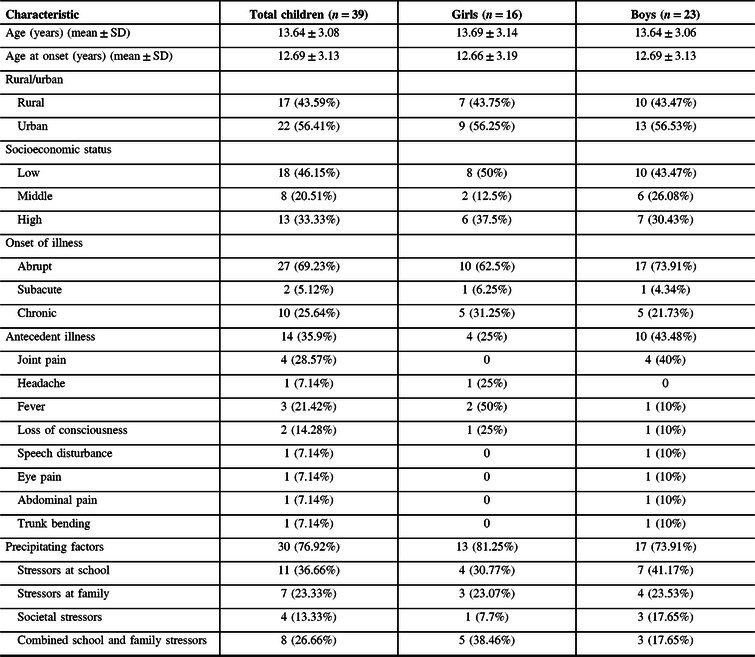

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics (Table 1)

Thirty-nine children (16 girls and 23 boys) were evaluated during the 9-year period (2011–2020). The mean age at onset was 12.69 ± 3.13 years with a median duration of illness being 150 days (range 2 days– 6 years). About 56.4% of children were from urban regions. Majority (66.7%) of the children belonged to low-to-middle socioeconomic strata (low – 46.15%; middle – 20.51%). The onset of the illness was acute in 69.23% and chronic presentation in 25.64%. Antecedent illness was observed in 14 children with joint pains being the most common (28.57%). Other antecedent illnesses that were noted included fever (21.42%), loss of consciousness (14.28%), headache (7.14%), speech disturbance (7.14%), eye pain (7.14%), and abdominal pain (7.14%). Thirty children were found to have a precipitating factor in the form of stressors at school (36.66%), combined school and family stressors (26.66%), family stressors (23.33%), and societal pressures (13.33%).

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics of the children

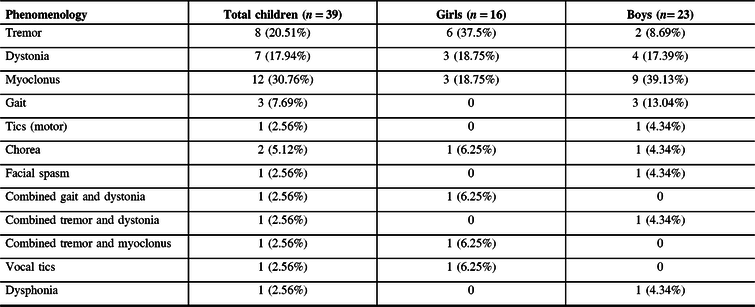

FMD Phenomenology (Table 2)

Table 2: Phenomenology of the movement disorders observed in children

Myoclonus was the most common phenomenology observed in these patients (30.76%), followed by tremor (20.51%), dystonia (17.94%), and gait abnormality (7.69%). Chorea (5.12%) and tics (2.56%) were uncommon. Tremor (37.5%) and dystonia (18.75%) were more common in girls, whereas myoclonus was more common in boys (30.76%). Gait abnormality was seen exclusively in boys (13.04%). Multiple FMD phenomenologies were seen in two girls and one boy. One girl presented with functional vocal tics and one boy with functional dysphonia.

Course and Outcome

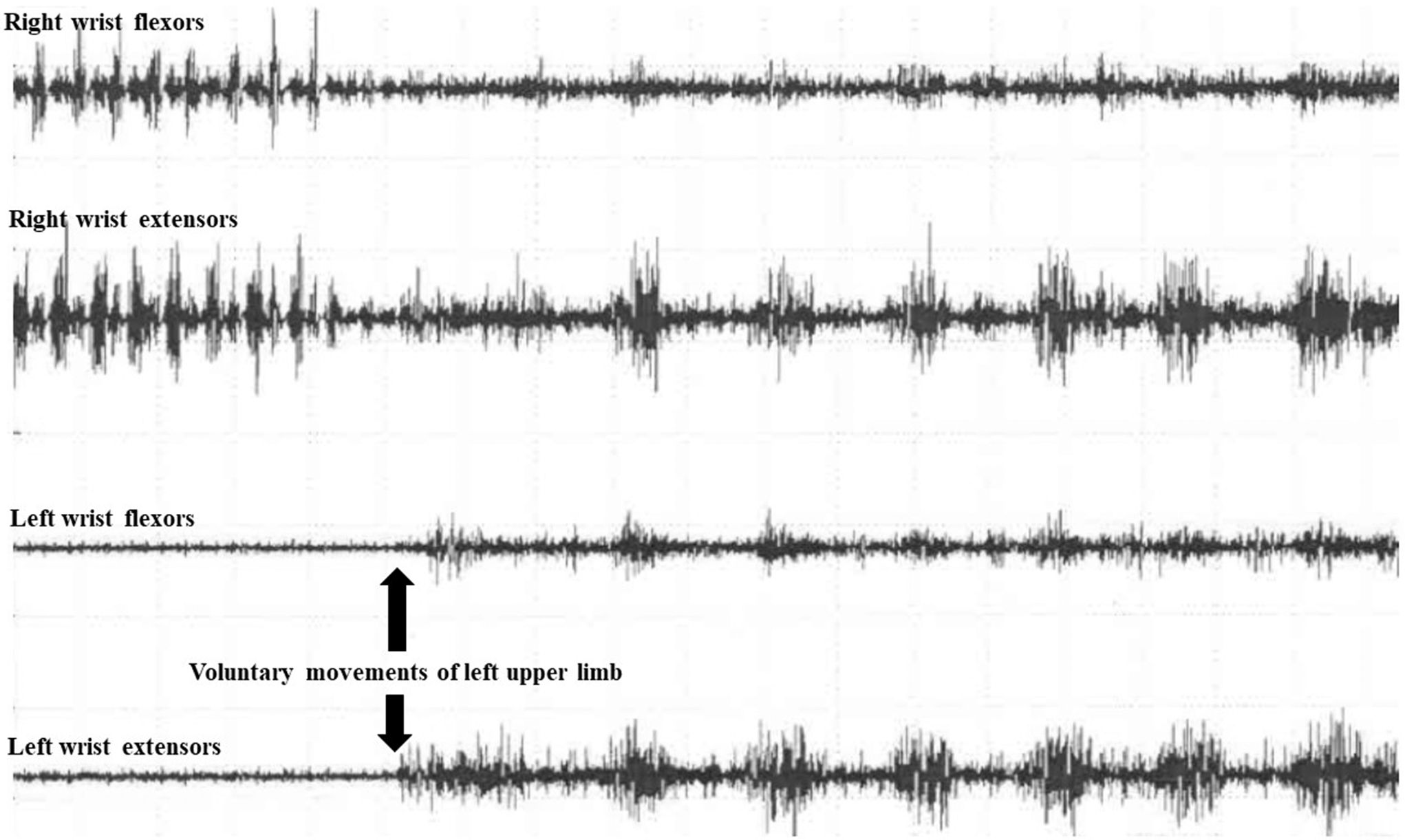

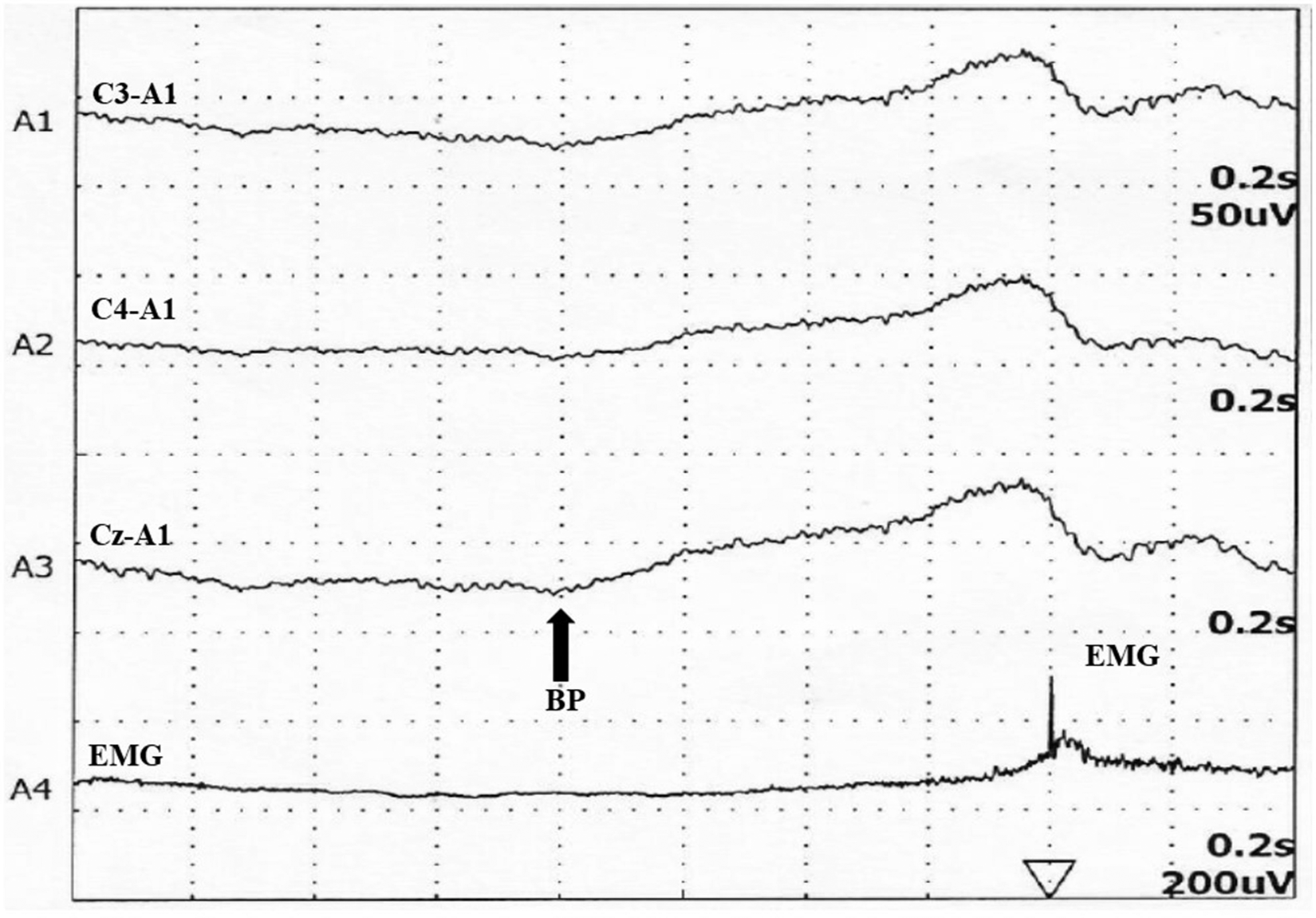

Electrophysiological testing was performed in 17 children (43.58%) and FMD was confirmed in all of them. In patients with functional tremors, surface EMG showed variability, distractibility (Figure 1), and entrainability (Figure 2). BP was demonstrated in some patients with myoclonus (Figure 3). Placebo response was observed in 30.6% of children. Nineteen children (48.71%) required hospital admission. Twenty-two (56.41%) showed complete resolution of the symptoms and in 11.1%, there was a partial improvement. All 39 children in our study were referred to child psychiatry specialists for detailed evaluation and majority (n = 37, 94.9%) of them were diagnosed with a dissociative movement disorder. Associated psychiatric comorbidity was observed in 12.8% in the form of obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, generalized anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, and psychosis.

Figure 1: Distractibility in a patient with functional tremor. During the mental task, there is abrupt cessation of tremor in the right upper limb.

Figure 2: Entrainability in a patient with functional tremor. During voluntary movements of the left upper limb, there is abrupt cessation and change in the tremor frequency and amplitude in the right upper limb.

Figure 3: Bereitschaftspotential (BP) in a child with functional myoclonus. BP is seen about 800 msec before the electromyogram (EMG) activity.

Discussion

FMDs are heterogeneous disturbances of motor function that are not explained by organic conditions and may occur in association with underlying psychiatric disease.Reference Schwingenschuh, Pont-Sunyer and Surtees12 FMD poses a great challenge for clinicians in diagnosis and management.

In our study, 39 children with documented and clinically established FMD were evaluated. The most common type of FMD observed was myoclonus, tremor, and dystonia. The exact prevalence or frequency of pediatric FMD varies between 2% and 3% of children attending the movement disorders clinic.Reference Ferrara and Jankovic2,Reference Schwingenschuh, Pont-Sunyer and Surtees12,Reference Fernández-Alvarez13 In a study involving 2280 children with neurological disorders, psychogenic etiology was observed in 6.4%.Reference Thomas14

In our study, FMD was more common in boys, which is similar to the previous two studies from India.Reference Kamble, Prashantha and Jha3,Reference Pandey and Koul15 However, some previous studies have shown the higher prevalence in girls.Reference Ferrara and Jankovic2,Reference Schwingenschuh, Pont-Sunyer and Surtees12,Reference Ahmed, Martinez and Yee16,Reference Canavese, Ciano and Zibordi17 In another study from our institute, about 48% of patients with the then-existing diagnostic category of hysteria were girls.Reference Srinath, Bharat and Girimaji18 The reason for predominance of FMD in boys is not clear, but it may be due to sociocultural practices prevailing in the Indian community wherein medical attention is sought more often and earlier for the boys than girls. Indian society is mainly patriarchal.Reference Prusty and Kumar19 There is a preference for a son in most of the Indian families and there is discrimination against girls especially in providing education and medical care.Reference Arnold, Choe and Roy20

In our study, majority of the children belonged to low-to-middle socioeconomic strata. In India, patients from low-to-middle socioeconomic populations more often visit government hospitals, like ours. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no published literature from India on the prevalence of pediatric FMD based on socioeconomic status.

Abrupt onset of symptoms is one indicator toward FMD, which was seen in 69.2% of our cohort. In a study of 54 children, approximately 90% of children presented with an abrupt onset.Reference Ferrara and Jankovic2 Many other studies have also reported a preponderance of abrupt onset of illness.Reference Canavese, Ciano and Zibordi17 In addition, antecedent illness is commonly seen in these patients. In our study, nearly a third of the children had an antecedent illness which is similar to the other studies.Reference Kamble, Prashantha and Jha3,Reference Canavese, Ciano and Zibordi17

History of precipitating factors needs to be enquired in patients suspected of FMD. Most of the studies have reported precipitating factors ranging from 47.9% to 83.7% in adults.Reference Ertan, Uluduz and Ozekmekçi21,Reference Kim, Pakiam and Lang22 The various precipitating factors identified in these studies include physical injury, psychological insult, flu-like illness, death of a relative, poverty, family, or social stress.Reference Ertan, Uluduz and Ozekmekçi21–Reference Thomas, Vuong and Jankovic23

In a study involving 38 children, significant stressors were identified in 27 that included academic difficulties in school, punitive parent, parental discord, financial difficulties, increasing workload, and sibling rivalry.Reference Srinath, Bharat and Girimaji18 Traumatic experience (physical or psychological) and emotional factors in the childhood have a significant impact on the pathogenesis of FMD.

Myoclonus followed by tremor and dystonia were the common phenomenologies observed in our study. However, tremorReference Ferrara and Jankovic2,Reference Canavese, Ciano and Zibordi17,Reference Srinath, Bharat and Girimaji18 and dystoniaReference Schwingenschuh, Pont-Sunyer and Surtees12,Reference Faust and Soman24 have been the most common FMD in other studies.

Detailed psychiatry evaluation is necessary for diagnosis and treatment of FMD. The various psychiatric comorbidities that have been associated with FMD include obsessive-compulsive disorders, depression, and anxiety.Reference Voon, Brezing and Gallea25

Clinically, it is challenging to diagnose FMD. However, some cues that may be useful for diagnosis can be categorized as historical (abrupt onset, static course, psychiatric comorbidity, precipitating factors, presence of multiple somatizations, pending litigation, etc.), clinical (incongruence, inconsistency, distractibility, variability, entrainability, fluctuating course, suggestibility/modulation, episodic occurrence with complete or incomplete remissions, spontaneous remissions, and additional movement disorders), and treatment related (response to psychotherapy, placebo).Reference Kim, Pakiam and Lang22 Electrophysiological methods such as surface EMG recording for tremors and BP in myoclonus may be helpful in determining the functional basis for the movement disorders.Reference Kamble, Prashantha and Jha3

Recent neuroimaging studies have implicated abnormal emotional processing, sense of agency, and top-down regulation from frontal areas as important pathophysiological components in FMD.Reference Voon, Brezing and Gallea25 Abnormal regional brain activations and functional connectivity have been demonstrated using functional MRI and positron emission tomography (PET).Reference Stone, Zeman and Simonotto26 Abnormal connectivity is found in right caudate, amygdala, prefrontal, and sensorimotor regions in patients with FMD with over 68% sensitivity and specificity.Reference Wegrzyk, Kebets and Richiardi27 In addition to the abnormal activation of supplementary motor area (SMA), patients with functional tremors and dystonia have abnormal activation in the right middle temporal gyrus or right temporoparietal junction.Reference Espay, Maloney and Vannest28 The cingulate cortex has been implicated in self-awareness, self-monitoring, and active motor inhibition.Reference Aybek, Nicholson and O’Daly29 In patients with functional tremors and dystonia, there is abnormal activation of the cingulate cortex.Reference Hedera30 In future, these advanced imaging techniques may be useful in the diagnosis of FMD. Currently, these studies have been done only in adults. There are no such studies in pediatric FMD.

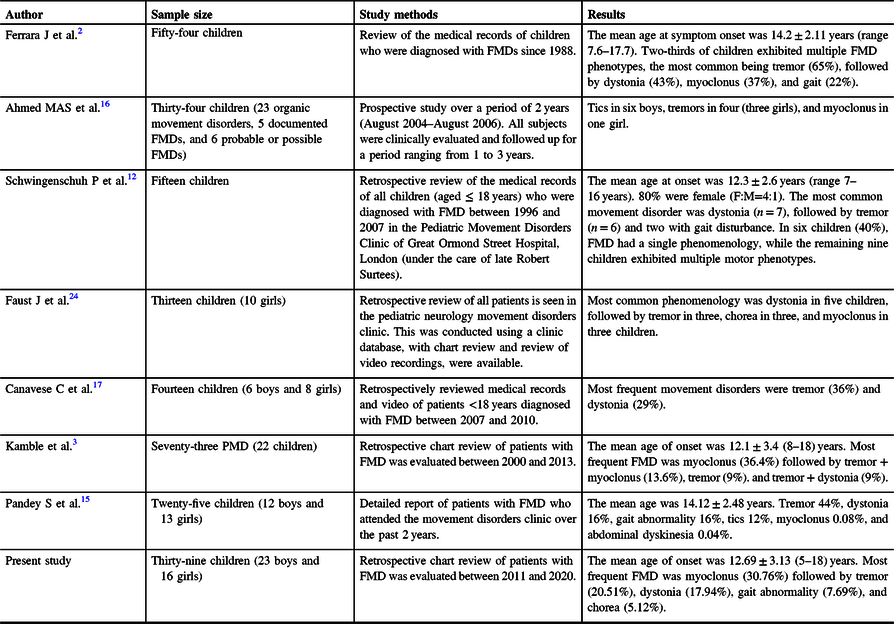

In our study, 56.4% of children had complete resolution of symptoms, and in 11.1%, there was a partial improvement and 13.9% showed no improvement at all, which may be due to non-acceptance of functional nature of the disease by parents/patients. There was no child with a worsening of symptoms. Studies have reported response rates ranging from 5% to 57%.Reference Thomas, Vuong and Jankovic23,Reference Hedera30–Reference Munhoz, Zavala and Becker33 Similar good outcome has been observed in previous studies from India.Reference Pandey and Koul15 In another study, the outcome was not described due to lack of follow-up which is a problem with patients with FMD.Reference Ferrara and Jankovic2 In a study by Schwingenschuh et al., 47% improved completely, 33% improved substantially, and 20% remained chronically and severely disabled.Reference Schwingenschuh, Pont-Sunyer and Surtees12 A summary of the previous and present studies is shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Spectrum of PMD phenomenology in other studies

Conclusions

In our study, we observed that FMD was more common in boys and myoclonus as the most common phenomenology. This is in sharp contrast to previous studies. This may be due to gender bias as well as social stigma in our country. The symptoms of FMD have a great impact on the mental health, social, and academic functioning of children. It is important to identify precipitating factors and associated psychiatric comorbidity in these children as prompt alleviation of these factors by engaging parents and the child psychiatrist will yield better outcomes. Electrophysiology and placebo effect may serve as useful supplementary tools for diagnosing FMD.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have any financial disclosure to make or have any conflict of interest.

Statement of Authorship

KR: Data collection, manuscript writing, study design, and data review.

NK: Data collection, manuscript writing, study design, and data review.

RY: Manuscript review.

AB: Data collection, statistical analysis.

VVH: Manuscript review.

MN: Manuscript review.

SS: Study design, supervision, data review, and manuscript review.

PKP: Conception of the study, study design, supervision, data review, and manuscript review.