INTRODUCTION

Cytotoxic brain edema, a predominant event following traumatic brain injury and cerebral infarct, is one of the major mortality factors. It is caused by a sustained intracellular accumulation of water in the brain.Reference Unterberg, Stover, Kress and Kiening 1 Glutamate, one of the principal neurotransmitters, has been shown to be associated with cytotoxic brain edema. Under normal physiological conditions, glutamate is released into nerve terminal synapses at millimolar concentrations and facilitates excitatory synaptic transmission. However, under ischemic conditions, extracellular glutamate levels increase by more than 150-fold within 30 minutes of the ischemic insult. This extraordinarily high level of glutamate triggers a massive influx of ions and water into cells, resulting in their extensive swelling.Reference Kahle, Simard, Staley, Nahed, Jones and Sun 2

Activation of pre-synaptic and post-synaptic glutamate receptors (GluRs) after substantial glutamate release has been implicated in cytotoxic edema formation following ischemia. An ischemic injury, for example, under conditions of oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD), causes a major energy failure and leads to a massive release of glutamate, which results in an excessive activation of GluRs. The activation of both ionotropic and metabotropic GluRs (iGluR and mGluR, respectively) stimulates an ion influx through isoform 1 of Na+-K+-Cl− cotransporters (NKCC1).Reference Su, Kintner and Sun 3 , Reference Khanna, Kahle, Walcott, Gerzanich and Simard 4 Activation of iGluRs, in particular that of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors (NMDARs), causes a marked water influx via water channel proteins. This is accompanied by an excessive cation influx (mainly Na+, K+, and Ca2+) followed by anions (mainly Cl−), all contributing to the ensuing cytotoxic edema formation.Reference Liang, Bhatta, Gerzanich and Simard 5

We have been studying the effects of low-intensity ultrasound (LIUS), a special type of noninvasive mechanical stimulation, to explore its latent therapeutic potentials in several disease models. In previous studies, we have demonstrated the cytoprotective, anti-inflammatory, and anti-oxidative effects of LIUS stimulation in various cell types and disease models including brain edema,Reference Karmacharya, Kim and Kim 6 Parkinson’s disease,Reference Karmacharya, Hada, Park and Choi 7 eye disease,Reference Kim, Kim, Choi, Park and Choi 8 , Reference Karmacharya, Hada, Park and Choi 9 arthritis,Reference Chung, Barua, Choi, Min, Han and Baik 10 and others.Reference Choi, Kim, Karmacharya, Min and Park 11 In particular, we have shown that LIUS stimulation inhibits brain edema formation in rat brains by altering the localization of the water channel protein aquaporin-4 (AQP4) in astrocytic foot processes.Reference Karmacharya, Kim and Kim 6 However, the mechanism of the OGD-induced edema in our model and the upstream mechanism of the LIUS action leading to the modulation of AQP4 functions remain largely unsolved.

In this study, we investigated further into the mechanisms of LIUS-induced inhibition of edema formation in an in vitro model of ischemia in acutely prepared rat hippocampal slices. It would be relevant here to note that hippocampal slice culture model has long been used as a well-known and well-established model for the study of various brain diseases,Reference Cho, Wood and Bowlby 12 , Reference Holopainen 13 including ischemic brain edema,Reference Dong, Schurr, Reid, Shields and West 14 owing to its important clinical and pre-clinical therapeutic applications. As the activation of NMDARs has been implicated in cytotoxic edema by activating AQP4 functions via phosphorylation,Reference Xiao 15 we thought primarily that NMDARs, whose activation precedes that of AQP4 and NKCC1 in signal hierarchy of the cytotoxic edema formation, could be the upstream targets of LIUS. Furthermore, because NMDAR subunits have been reported to be highly sensitive to mechanical stimulation,Reference Singh, Doshi and Spaethling 16 we assumed that LIUS could modulate NMDAR functions directly. In this study, we first establish that exposure of rat hippocampal slices to either ischemic conditions or the iGluR agonist NMDA induces edema. In addition, we explore the action of ultrasound stimulation on the NMDA-induced edema formation and discuss a possible mechanism by which ultrasound treatment resolves the edema. We demonstrate that ultrasound stimulation changes the levels of tyrosine-phosphorylated NR2A subunit of NMDARs, which might help prevent edema progression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animals used in this study were treated in accordance with the ethical procedures outlined by the INHA University-Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Chemicals and Antibodies

N-Methyl-d-aspartic acid was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). The selective group I mGluR agonist (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Abingdon, UK). The rabbit polyclonal anti-NMDAR2A (phospho Y1325) antibody was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). The mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody and the horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rat or anti-mouse secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). For intraperitoneal anesthesia, tiletamine–zolazepam was purchased from Virbac Laboratories (Carros, France) and xylazine from Bayer (Gyeonggi-do, Korea).

Preparation of Hippocampal Slices and Induction of Edema In Vitro

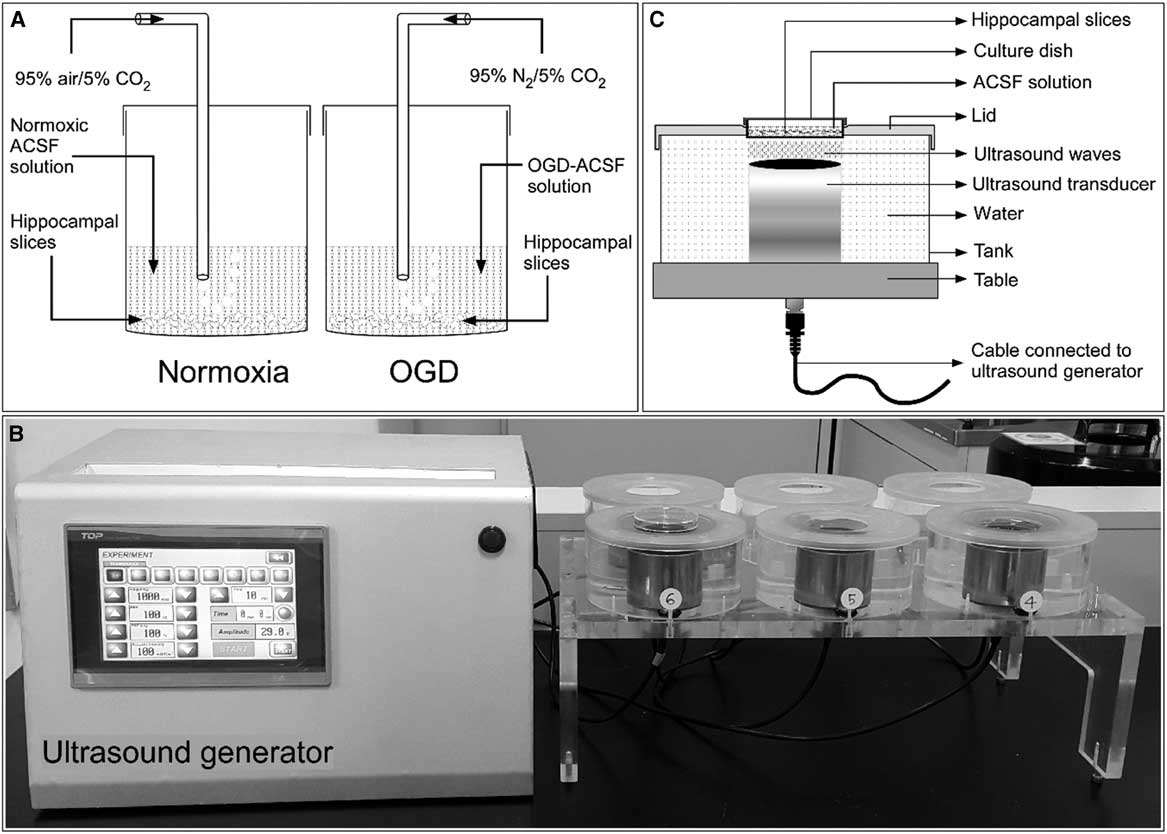

Hippocampal slices were prepared as described in our previous publication.Reference Karmacharya, Kim and Kim 6 Briefly, male Sprague–Dawley rats (body weight=280-300 g) were anesthetized with 50 mg/kg tiletamine–zolazepam and 10 mg/kg xylazine intraperitoneally. The anesthetized rats were decapitated, and the cranium was opened. The brain was rapidly removed and immediately immersed in iced normoxic artificial CSF (ACSF) solution composed of 124 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 10 mM glucose, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MgCl2, exhibiting an osmolarity of 305-315 mOsmol. To achieve normoxia, the ACSF was equilibrated with 95% O2/5% CO2. The brain was cut longitudinally to separate the two hemispheres, and the hippocampi were scooped out from both hemispheres. The hippocampi were immediately added into iced ACSF solution. Each hippocampus was mounted on the stage of a tissue chopper (McIlwain Tissue Chopper; Mickle Laboratory Engineering, Surrey, UK), and slices of 400-μm thickness were prepared from both hippocampi. After cutting, all slices were separated and maintained in ACSF solution for 2 hours at room temperature (20-25°C) before further experimentation (Figure 1A).

Figure 1 General experimental setup. (A) Schematic showing incubation of rat hippocampal slices in normoxic and oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) conditions. (B) A self-manufactured ultrasound generator connected to the ultrasound exposure system. (C) Schematic diagram with proportional dimensions representing the geometry and positioning of the ultrasound exposure system. ACSF=artificial CSF.

Ischemic edema was induced in these acutely prepared hippocampal slices by incubating them for 1 hour in an oxygen- and glucose-deprived ACSF solution. This OGD solution consisted of 124 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 10 mM mannitol, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 2 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MgCl2 with an osmolarity of 305-315 mOsmol and was equilibrated with 95% N2/5% CO2.

Ultrasound Stimulation

Hippocampal slices were stimulated with LIUS, as described in our previous publication.Reference Karmacharya, Kim and Kim 6 Briefly, a self-manufactured ultrasound generator that produces ultrasonic waves of 1 MHz frequency was set to continuous mode. The intensity and the treatment time can be controlled in this apparatus (Figure 1B). The hippocampal slices in their cell culture dishes were placed on ultrasound transducers and stimulated by ultrasound with acoustic intensities of 30, 50, or 100 mW/cm2 for 20 minutes before further drug or OGD treatment (Figure 1C). All experiments included a control group consisting of hippocampal slices incubated in normoxic ACSF solution without any chemical treatment or ultrasound stimulation.

Water Content Analysis

The edema formation in hippocampal slices was evaluated by determining the water content in percent for each slice. The method used has been published previously.Reference Karmacharya, Kim and Kim 6 Briefly, immediately following incubation, hippocampal slices were weighed on a microbalance on pre-weighed aluminum foils, and the weights measured were considered as the “wet weight.” After a 24-hour period of desiccation at 80°C, the slices were weighed again and recorded as the “dry weight.” The water content was calculated using the following formula:

Western Blotting Analysis

The hippocampal slices were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer with the composition of 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 100 μM Na3VO4, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 50 μg/mL phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The concentrations of protein were determined using Bradford assays. In all, 30 μg of proteins per sample were fractionated on polyacrylamide gels, and the resulting bands were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-NMDAR2A (phospho Y1325) antibody (1:1000) or mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (1:3000) overnight at 4°C. After thorough washing, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1000). The signals were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Data in this study are provided as mean value±standard error of mean. Statistical analysis of experimental data was performed using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis. Statistical significance was assigned as *, #, §, or ‡ for p<0.05; **, ##, §§, or ‡‡ for p<0.01; and ***, ###, §§§, or ‡‡‡ for p<0.001.

RESULTS

Ischemic Edema in Rat Hippocampal Slices Involves Activation of N-Methyl-d-Aspartic Acid Receptors

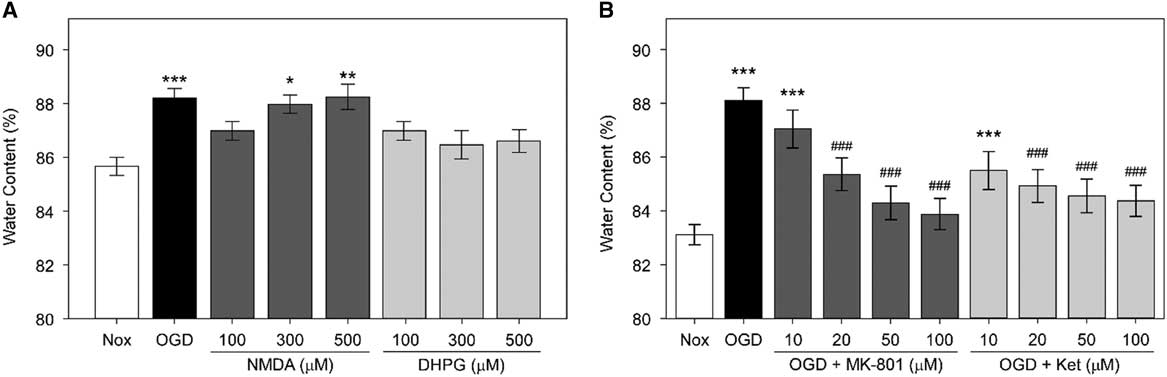

First, we examined whether NMDARs are involved in the OGD-induced edema formation in hippocampal slices (Figure 2A). The average water content of rat hippocampal slices incubated in OGD-ACSF solution was 88.05±0.46% compared with 83.06±0.38% in the non-treated normoxic group (Nox; p<0.001). We found that two NMDAR antagonists, MK-801 and ketamine,Reference de Bartolomeis, Sarappa and Buonaguro 17 inhibited the OGD-induced edema at 10, 20, 50, and 100 μM in a concentration-dependent manner (p<0.001 for 20, 50, and 100 μM of each inhibitor). The average water content of rat hippocampal slices incubated under OGD conditions and treated with 50 or 100 μM MK-801 were 84.30±0.44% and 83.89±0.41%, respectively, whereas those treated with 50 or 100 μM ketamine were 84.61±0.44% and 84.37±0.31%, respectively. These values are significantly lower than those of the OGD group and comparable to the values in the untreated normoxic group.

Figure 2 Role of N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor (NMDARs) in oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD)-induced edema in rat hippocampal slices. (A) Average water content of rat hippocampal slices exposed to OGD, NMDA, or (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG). Rat hippocampal slices were incubated in OGD-artificial CSF (ACSF) solution or were treated with NMDA or DHPG at 100, 300, or 500 μM in normoxic ACSF for an hour. Rat hippocampal slices incubated in normoxic ACSF for an hour without any treatment (Nox) are included. Statistical significance levels compared with Nox are indicated by * (n=10, each). (B) Average water content of rat hippocampal slices treated with OGD and NMDAR antagonists. Rat hippocampal slices were incubated for an hour in OGD-ACSF solution in the presence or absence of the NMDAR antagonists MK-801 or ketamine (Ket) at a concentration of 10, 20, 50, or 100 μM. Rat hippocampal slices incubated in normoxic ACSF solution for an hour without any treatment (Nox) are included as control. Statistical significance for experimental groups is presented as * or # in comparison to Nox or OGD, respectively (n=10, each).

Next, we examined whether NMDA (an iGluR agonist) and DHPG (a selective mGluR agonist) induce edema by themselves. We observed that only treatment with NMDA, but not with DHPG, led to significant edema in brain slices (Figure 2B). The water content of NMDA-treated slices increased in a concentration-dependent manner. Notably, the average water contents of slices incubated in the presence of 300 or 500 μM NMDA were 87.99±0.24% and 88.22±0.4%, respectively. Therefore, these values were comparable to those of the OGD group (88.23±0.36%) and significantly higher than those of the untreated Nox group (85.55±0.26%). However, there was only a slight and statistically insignificant increase in the water content of slices incubated with similar concentrations of DHPG. The average water contents in slices incubated in the presence of 100, 300, and 500 μM DHPG were 87.27±0.44%, 86.41±0.46%, and 86.6±0.37%, respectively.

Ultrasound Stimulation Reduces N-Methyl-d-Aspartic Acid-Induced Edema

Next, we assessed the effects of direct ultrasound stimulation on NMDA-treated rat hippocampal slices. We found that ultrasound stimulation, particularly at an intensity of 100 mW/cm2, inhibited edema significantly in slices exposed to either OGD or 500 μM NMDA (Figure 3A). Average water contents of LIUS-stimulated versus nonstimulated groups were 85.91±0.5% versus 88.51±0.3% for OGD (p<0.001), 85.72±0.32% versus 88.95±0.35% for NMDA (p<0.001), and 86.22±0.44% versus 87.74±0.54% for DHPG. All ultrasound-stimulated groups exhibited water contents that were comparable to those of the normoxic group (86.23±0.48%).

Figure 3 Effects of ultrasound stimulation (US) on N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA)- or (S)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG)-induced edema in rat hippocampal slices. (A) Average water content of rat hippocampal slices treated with NMDA or DHPG with or without US. Rat hippocampal slices were incubated for an hour in oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD)-artificial CSF (ACSF) solution or were treated with 500 μM NMDA or DHPG in normoxic ACSF with or without US at 100 mW/cm2 for 20 minutes before incubation. Rat hippocampal slices incubated in normoxic ACSF solution for an hour without any treatment (Nox) are included as the control group. Statistical significance levels between experimental groups are indicated by * compared with Nox, by # compared with OGD, or by § compared with NMDA (n=10, each). (B) Average water content of rat hippocampal slices stimulated with ultrasound at various acoustic intensities. Rat hippocampal slices were incubated for an hour in OGD-ACSF solution, or treated with 500 μM NMDA in normoxic ACSF with or without US at 30, 50, or 100 mW/cm2 for 20 minutes before incubation. Rat hippocampal slices incubated in normoxic ACSF solution for an hour without any treatment (Nox) are included. Statistical significance levels are shown as * or # in comparison with Nox or NMDA, respectively (n=10, each).

Furthermore, we found that the inhibitory effects of ultrasound stimulation against NMDA-induced edema were intensity-dependent (Figure 3B), with the ultrasound intensity of 100 mW/cm2 being the most potent stimulus. The average water content of slices in the NMDA-treated group without ultrasound stimulation was 88.47±0.23%, whereas the mean values in LIUS-stimulated groups were 87.45±0.17%, 86.42±0.22% (p<0.01), and 84.74±0.39% (p<0.001) for 30, 50, and 100 mW/cm2, respectively. Particularly, the water content of the 100 mW/cm2 ultrasound group was comparable to that of the untreated normoxic group (84.78±0.36%).

Ultrasound Stimulation Decreases Oxygen and Glucose Deprivation- or N-Methyl-d-Aspartic Acid-Induced Phosphorylation of N-Methyl-d-Aspartic Acid Receptors

It has been shown previously in in vitro models of ischemia that an increased phosphorylation of NMDARs is involved in OGD-induced edema.Reference Pavlov and Mielke 18 , Reference Takagi 19 In accordance with these studies, we found that both OGD (Figure 4A) and NMDA treatments (Figure 4B) increased the amount of phosphorylated NR2A subunits of the NMDAR in rat hippocampal homogenates. The levels of phosphorylated NR2A subunits in the OGD- or NMDA-treated group were more than threefold (p<0.001) the level in the normoxic group. Interestingly, the OGD- or NMDA-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of NMDAR subunits was decreased by ultrasound stimulation in an intensity-dependent manner. In particular, the 50 and 100 mW/cm2 ultrasound groups showed nearly a 30% and 50% (p<0.001) decrease, respectively, in the levels of phosphorylated NMDAR compared with that in the OGD group without ultrasound treatment. Similarly, ultrasound stimulation at 50 and 100 mW/cm2 decreased the phosphorylated NMDAR by nearly 50% (p<0.001) after NMDA treatment.

Figure 4 Effect of ultrasound stimulation (US) on tyrosine phosphorylation of the NR2A subunit of N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor (NMDARs). Rat hippocampal slices were incubated for an hour in oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD)-artificial CSF (ACSF) solution (A) or in normoxic ACSF containing 500 μM NMDA (B) with or without US at 30, 50, or 100 mW/cm2 for 20 minutes before incubation. Rat hippocampal slices incubated in normoxic ACSF solution for an hour without any treatment (Nox) are included. The hippocampal slices were minced and homogenized in RIPA buffer. Total proteins were extracted from the homogenate, and 30 μg of each extract was used for Western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Statistical significance levels between experimental groups are shown as * or as # compared with Nox or OGD (A)/NMDA (B), respectively. n=3 for each experiment.

DISCUSSION

Brain edema, a major causal factor for morbidity and mortality in a wide variety of nervous system disorders, is a pathological condition characterized by a net increase in brain water content, brain tissue volume, and intracranial pressure. This results in brain herniation, irreversible brain damage, and eventually death.Reference Papadopoulos, Saadoun, Binder, Manley, Krishna and Verkman 20 We have previously demonstrated that LIUS stimulation significantly reduces OGD- and glutamate-induced edema formation in the rat brain by reducing the expression and altering the localization of AQP4 water channels in astrocytic foot processes.Reference Karmacharya, Kim and Kim 6 Excessive release of glutamate has been implicated in the pathophysiology of cytotoxic brain edema.Reference Stokum, Gerzanich and Simard 21 A massive release of glutamate activates NMDARs, a member of the iGluR family, which initiates a significant increase in intracellular Na+ and Cl− ion concentrations.Reference Liang, Bhatta, Gerzanich and Simard 5 Activation of NMDARs has been attributed to tyrosine phosphorylation of its subunits. In particular, transient ischemia increases tyrosine phosphorylation of the NR2A and NR2B subunits of the NMDAR in the rat hippocampus.Reference Takagi, Sasakawa, Besshoh, Miyake-Takagi and Takeo 22 , Reference Takagi, Shinno, Teves, Bissoon, Wallace and Gurd 23 In this study, we further explore the mechanisms of OGD-induced edema. We show, in addition to previously published results, that OGD-induced edema is mediated by activation of NMDARs and that this mechanism involves increased phosphorylation of the NR2A subunits of NMDARs. We demonstrate that, under normoxic conditions, hippocampal slices incubated with 300 or 500 μM NMDA exhibit a significantly higher water content than those without any treatment. However, the mGluR agonist DHPG induces only a slight and statistically nonsignificant increase in the water content. Furthermore, treatment with the NMDAR inhibitors MK-801 or ketamine reduced the OGD-induced edema in a concentration-dependent manner, albeit the inhibitory action of ketamine was less prominent than that of MK-801. It is of relevance here to note that MK-801 exhibits a greater potency on GluN2A and GluN2B subunits of NMDARs, whereas ketamine binds with higher affinity to the GluN2C subunit.Reference Sleigh, Harvey, Voss and Denny 24 In addition, it has been reported earlier that OGD upregulates NMDAR subunits, which was inhibited by MK-801.Reference Neuhaus, Burek and Djuzenova 25 On the basis of these findings, we reasoned that NMDARs, rather than the mGluRs, might play a substantial role in the ischemia-induced cytotoxic edema in hippocampal slices in vitro. This is consistent with previous findings showing that an excessive activation of NMDARs caused by OGD-induced extracellular glutamate release is one of the key factors in cytotoxic edema formation.Reference Xiao 15 In addition, it has been reported that a high expression level of NMDARs is associated with the severity of an ischemic injury, supporting a major role of NMDARs in the development of brain edema.Reference Choi and Rothman 26

We have previously reported that ultrasound stimulation for 20 minutes with an acoustic intensity of 100 mW/cm2 inhibits OGD- and glutamate-induced edema.Reference Karmacharya, Kim and Kim 6 As we and othersReference Rungta Ravi, Choi Hyun and Tyson John 27 confirmed that OGD-induced edema involves the activation of NMDARs, we next determined whether ultrasound stimulation inhibits the development of NMDA-induced edema in rat hippocampal slices. Notably, NMDARs are mechanosensitive and exhibit a unique shift in actions following mechanical stimulation.Reference Singh, Doshi and Spaethling 16 It has been shown that mechanical stimulation can act as a distinct regulator of NMDAR functions. For instance, rapid neuronal stretching has been shown to induce a loss of the voltage-dependent Mg2+ block in NMDARs.Reference Zhang, Rzigalinski, Ellis and Satin 28 In the light of these reports, we hypothesized that LIUS, a type of mechanical stimulation, might exert effects on the NMDA-induced edema formation. Interestingly, we observed that ultrasound stimulation inhibits NMDA-induced edema in an intensity-dependent manner. The water content of hippocampal slices after ultrasound stimulation with an intensity of 100 mW/cm2 was significantly lower than that in the NMDA-treated group without ultrasound treatment and was comparable to that of the untreated normoxic group.

Studies on the mechanisms of ischemia-induced edema implicate enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation of NMDAR subunits.Reference Pavlov and Mielke 18 We too observed that both OGD and NMDA treatments increase the levels of tyrosine-phosphorylated NR2A subunits. Interestingly, we found that LIUS stimulation decreases tyrosine phosphorylation of the NR2A subunit in an intensity-dependent manner in both OGD and NMDA treatments. Thus, our data show that NMDARs are sensitive toward LIUS stimulation and that this stimulation can modulate the phosphorylation state of NMDARs. We think that LIUS stimulation might decrease the tyrosine phosphorylation and inhibit the overactivation of NMDARs, thereby reducing the subsequent ion influx into hippocampal cells. We propose NMDARs as the potential target of the observed ultrasound effects on the basis of previous reports that demonstrate that NMDAR subunits are mechanosensitive Reference Singh, Doshi and Spaethling 16 , Reference Ma, Huang, Chen and Lee 29 and that mechanical stress activates NMDARs.Reference Maneshi, Maki and Gnanasambandam 30 We think that ultrasound waves as a type of mechanical stimulation might decrease tyrosine phosphorylation of NMDARs and thus affect and modulate NMDAR functions. The LIUS-induced decrease of NMDAR functions might result in an inhibition of the ischemia-induced edema. However, it should be mentioned that further experimental evidence is needed to elucidate the mechanism by which ultrasound stimulation decreases tyrosine phosphorylation of NMDARs. Toward downstream pathways, it has been shown previously that NMDARs mediate protein phosphorylation and can stimulate neuronal gene expression via intracellular signaling such as the Ras–mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) or the transcription factor cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein pathways.Reference Sala, Rudolph-Correia and Sheng 31 Similarly, protein phosphorylation can regulate the function of AQP4 water channels.Reference Han, Wax and Patil 32 Hence, it is possible that an LIUS-induced decrease in NMDAR activation might affect subsequent protein phosphorylation and eventually reduce AQP4 activity as well, which further helps to reduce water influx into cells and thereby inhibits the formation of brain edema.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrate that OGD-induced edema in hippocampal slices is mediated by activation of NMDARs and that LIUS stimulation reduces the OGD- or NMDA-induced edema formation. In addition, LIUS stimulation prevents the OGD-induced increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of NR2A subunits of the NMDAR. Considering these data, we conclude that the inhibition of OGD-induced edema formation by LIUS stimulation possibly involves an inactivation of NMDARs and their downstream signaling pathways. N-Methyl-d-aspartic acid receptors as mechanosensitive channels could be a potential target of LIUS effects, but further investigations are required to elucidate the exact mechanism of LIUS action.

Acknowledgment

The study was supported by an Inha University research grant (grant number 55821).

Statement of Authorship

This manuscript contains original data. All authors have made substantial contributions to this study. BH contributed to the conception and design of the study, performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript. MBK performed experiments, interpreted data, and revised the manuscript. SRP and BHC made substantial contributions to the conception of the manuscript, helped to interpret the data, and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the article.