Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease of the central nervous system that is an important cause of neurologic disability.Reference Kister, Chamot, Salter, Cutter, Bacon and Herbert1 MS disease modifying therapies (DMTs) lower relapse rates and may slow disability progression for patients with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS).Reference Tramacere, Del Giovane, Salanti, D’Amico and Filippini2 MS DMTs can be associated with significant risks, including liver injury,Reference Yoshida, Rasmussen and Steinbrecher3 lymphocytopenia,Reference Rosenkranz, Novas and Terborg4 progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy,Reference Carruthers and Berger5 or secondary autoimmunity.Reference Cossburn, Pace and Jones6

Effective laboratory monitoring systems are essential for optimal patient care and strategies for maximizing safety can vary regionally, although the literature in this area is sparse. We undertook a survey of Canadian MS clinicians in order to characterize physicians who prescribe MS DMTs (by province, size of MS patient population, and duration of practice), to determine what infrastructure and personnel they use in laboratory monitoring for each Health Canada-approved DMT. Our goal was to find opportunities to enhance patient safety.

Methods

Study Participants

A University of British Columbia research ethics-approved web-based (Qualtrics) survey was sent to the Canadian Network of MS Clinics (CNMSC) listserv in April 2018. The CNMSC is a national network of academic and community-based healthcare professionals dedicated to MS clinical care, research, and training, currently with 65 active neurologists (www.cnmsc.ca).

Survey Design

By completing the survey, the participants consented to have their data included for analysis. The survey included a total of 26 questions, including practitioner demographics and prescribing habits, infrastructure for current laboratory monitoring processes, practitioner’s level of concern with laboratory monitoring systems, and thoughts on automated laboratory monitoring systems. Since the burden of laboratory result monitoring in MS is highest with alemtuzumab, several questions were focused specifically on alemtuzumab risk mitigation. A copy of the survey is available in the supplementary material.

Results

Respondents

A total of 42 healthcare professionals from 8 different provinces responded to the survey (Table 1). Due to the limited number of responses from Saskatchewan and Manitoba, as well as Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, provinces were grouped together as Prairie Provinces and the Maritimes, respectively, for the remainder of the analysis. In order to gauge the overall response rate, 32/65 neurologists (49%) active in the CNMSC responded.

Table 1: Survey responses from all CNMSC members and only neurologists by province

DMT Prescribers

Experience level varied between DMT prescribers, with 11/34 (32%) practicing for less than 5 years and 14/34 (41%) practicing for over 15 years. The number of MS patients in the care of DMT prescribers also varied, with 8/34 (24%) of respondents following less than 500 patients, but 14/34 (41%) following more than 1000. While 25/34 (74%) DMT prescribers use an electronic medical record (EMR) in their clinics, 15/34 (44%) respondents received laboratory results either “all” or “mostly” on paper. Prescribers spend anywhere from “less than an hour” (7/34, 20%) to more than 3 hours each week reviewing laboratory results (3/34, 9%), with most respondents indicating either 1–2 hours or 2–3 hours (15/32 (47%) and 7/32 (22%), respectively).

Laboratory monitoring infrastructure was found to impact treatment recommendations, as 13/34 (38%) of DMT prescribers indicated that existing infrastructure for alemtuzumab monitoring impacted their comfort level for recommending the treatment. Of those 13, respondents offered comments such as “I fear there would be a significant delay before I am notified of a critical result,” “not comfortable with early detection of renal impairment,” and “receiving 3 months of labs at a time.”

When asked whether an automated laboratory monitoring surveillance for alemtuzumab would impact comfort with prescribing the medicine, 23/34 (68%) responded either “probably” or “maybe,” and 9(26%) respondents responding “no” and 2(6%) responding “not sure.”

Laboratory Monitoring Practices

Current laboratory monitoring practices are imperfect and 64% of respondents were aware of instances where their laboratory monitoring processes had failed. A variety of errors were reported including errors on laboratory requisitions, patient non-compliance, and errors in receiving data from laboratories (i.e., wrong provider sent data).

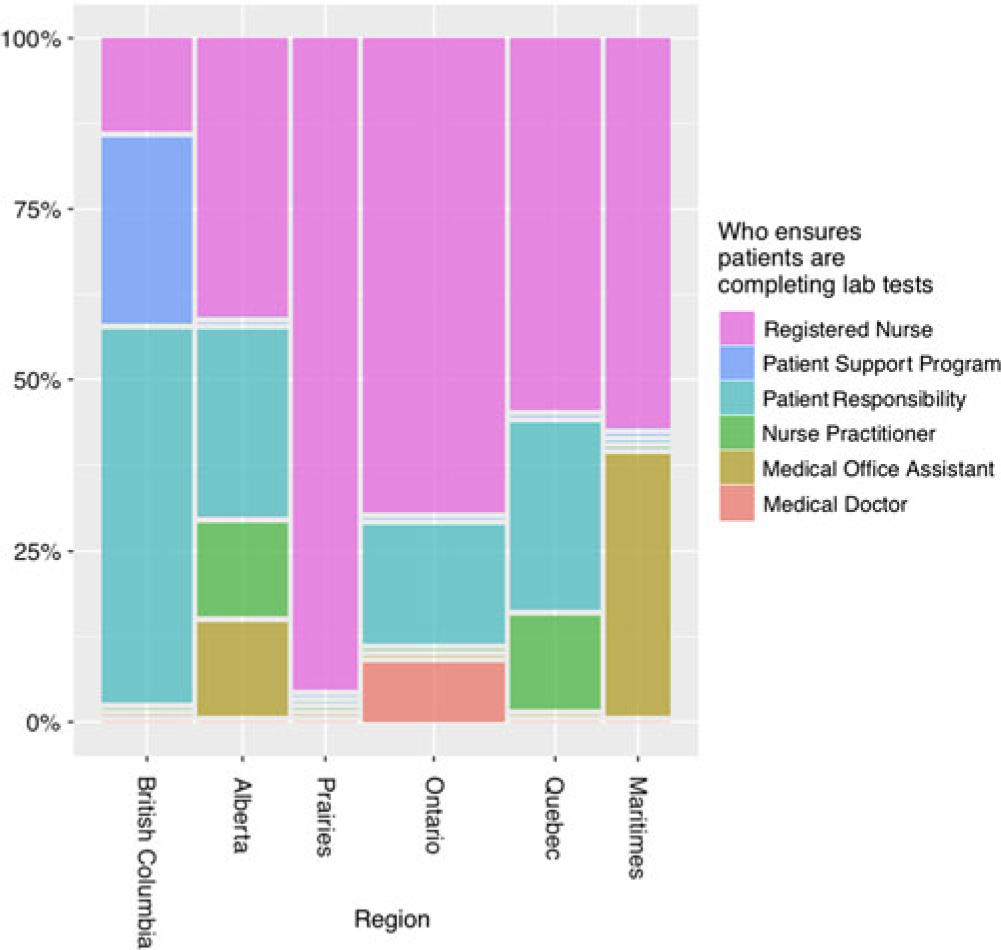

Figure 1 indicates that there is regional variation in the type of health care practitioner primarily responsible for ensuring patient monitoring compliance. Although all regions report using registered nurses (RN) in the laboratory monitoring process, the Prairie provinces and Ontario report more nursing involvement than British Columbia.

Figure 1: Responses to “who primarily ensures patients are completing lab work” by percentage in each region. There is regional variation in the health care practitioner primarily responsible for ensuring blood work completion.

Similarly, when asked about MS patients on DMTs where risk mitigation is not part of the patient support program, there was regional variability in the prominence of nursing-led laboratory monitoring compliance programs (Figure 2). In British Columbia and Ontario, respondents indicated more reliance on patient reporting and acknowledged that they did not know whether patients were completing laboratory monitoring.

Figure 2: Percentage of detection methods for patient non-adherence to laboratory monitoring process by region. Regions such as the Prairie provinces indicate using more nursing-led programs to monitor adherence while respondents from British Columbia and Ontario rely more on patient reports.

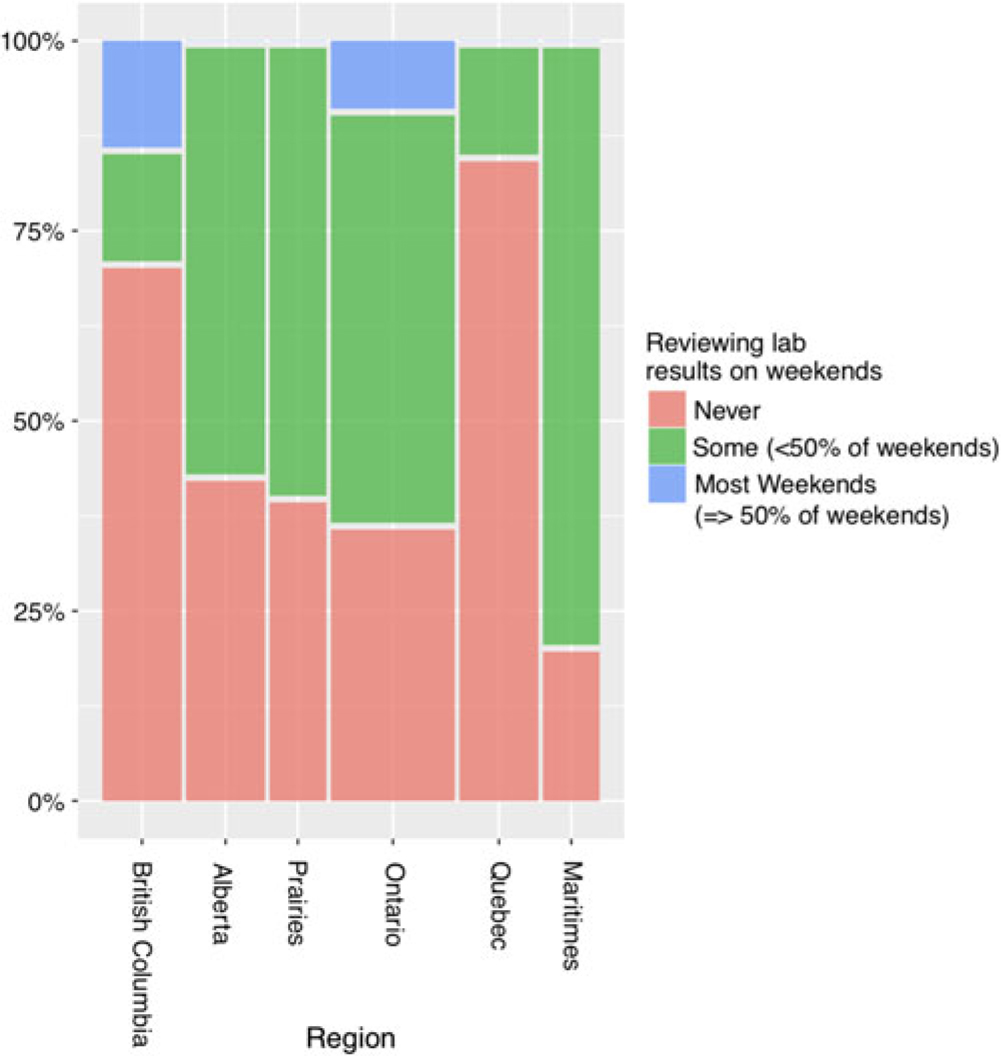

Respondents across Canada indicated a gap in laboratory monitoring surveillance over the weekends, with only a minority of respondents regularly reviewing laboratory results on more than 50% of weekends (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Percentage for how often lab results are reviewed on weekends by region. There is a gap in laboratory results surveillance, as many respondents report never reviewing results on weekends.

Concerns with Laboratory Monitoring for Health Canada-Approved Drugs

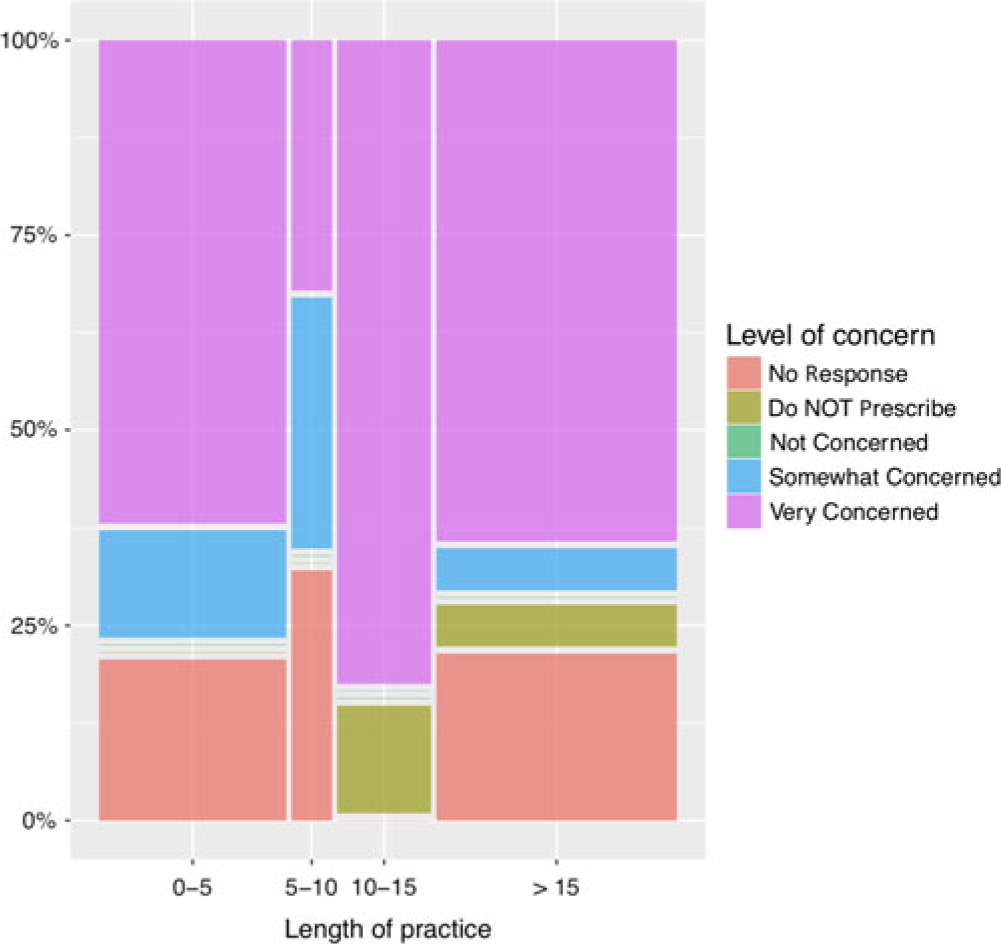

Respondents were asked to rate their level of concern with laboratory monitoring for each Health Canada-approved MS therapy (options included: not concerned, somewhat concerned, very concerned, or do not prescribe). Ninety-seven percentage of respondents reported being “not concerned” about glatiramer acetate monitoring. For alemtuzumab laboratory monitoring, 82% of respondents selected that they are “very concerned” and 12% “somewhat concerned.” Years in practice and volume of MS patients followed did not seem to alter reported perception of risks associated with medications such as alemtuzumab (Figure 4), ocrelizumab, or natalizumab.

Figure 4: Percentage for level of concern for alemtuzumab monitoring by length of practice in years. Perception of risk is similar among providers with different length of practice.

Discussion

This descriptive nationwide survey of MS clinicians yields several important observations. Prescribers have identified limitations in the current laboratory monitoring process, which may limit their use of higher efficacy medications that are associated with higher risk. While we had anticipated that clinicians with more exposure to MS patients would express lower levels of concern with DMTs requiring more monitoring, our respondents reported similar levels of concern with most MS DMT laboratory monitoring programs despite differences in duration of practice and patient volume.

Respondents indicated widespread implementation of EMRs, yet it is still common for DMT prescribers to receive laboratory results on paper, as opposed to codified imports into the EMR. This represents a barrier to leveraging codified laboratory data and medication data that would enable clinicians to search for patients in high-risk situations in their care. For example, at UBC Hospital, it is possible to search the EMR for patients whose usual medication list includes dimethyl fumarate and whose laboratory data indicate lymphocytopenia. Admittedly, since patient non-compliance was by far the most reported contributor to ineffective laboratory monitoring, EMR functionality as described above will not be a standalone solution for optimizing the laboratory monitoring process. In order to optimize patient compliance, the literature suggests that patient education of the risks associated with treatment, regular email reminders, and patient support programs may be beneficial.Reference Berger, Elovaara and Fredrikson7

DMT prescribers most commonly indicated taking 1–2 hours weekly to review laboratory results and it was rare for clinicians to review laboratory results on weekends, which may impact the timeliness of clinical intervention. In terms of clinical support for prescribers, we observed regional differences in the level of nursing involvement in laboratory compliance programs.

While there is regional variation in laboratory monitoring processes, we are not aware of established best practice in Canada, except when risk mitigation programs are available (as for alemtuzumab and natalizumab). The primary responsibility for lab monitoring rests with patients and physicians, but additional resources such as RN funding and risk mitigation programs help reduce the opportunity for errors. This study’s methodology does not allow comparisons of laboratory monitoring process efficacy. This study might offer insights that lead to development of “best practices” and development opportunities for MS neurologists practicing in Canada.

There are limitations to this survey including small sample size when comparing across more than one outcome, reporting bias, and structured nature of survey questions. For these reasons, statistical analyses were not undertaken. Future studies could benefit from a larger sample size and more open-ended, qualitative interview methods for more detailed information on the perception of laboratory monitoring systems.

Conclusions

In this descriptive survey of Canadian MS clinicians, we observed variability in laboratory monitoring infrastructure and personnel involved. Effective use of EMRs in patient safety might require elimination of paper laboratory results and facilitate use of internal safety queries. It is uncommon practice for clinicians to review laboratory results on weekends. There appears to be regional variability in nursing involvement in laboratory monitoring. Respondents’ perception of risk in laboratory monitoring was not associated with patient volume or duration of practice. The data suggest that there may be opportunities to optimize and standardize laboratory monitoring practices for MS DMT’s in Canada.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to CNMSC members for their participation. We also thank Tara Martin for developing the web-based Qualtrics survey.

Disclosures

KB has received compensation for consultation and a travel grant from Sanofi Genzyme. AT reports grants and personal fees from Biogen, grants and personal fees from Sanofi Genzyme, grants from Novartis, grants from Chugai, grants and personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Teva. RC reports personal fees from Biogen, personal fees from EMD Serono, personal fees from Sanofi Genzyme, grants and personal fees from Novartis, grants from MedImmune, grants and personal fees from Roche, grants and personal fees from Teva, and grants from Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, outside the submitted work. AA, AS, JH, and CT have nothing to disclose.

Statement of authorship

AA: data interpretation and manuscript preparation. AS: data interpretation and manuscript preparation. JH: survey design and interpretation. CT: statistical analysis of survey results. KB: project concept, survey design, data interpretation, manuscript preparation. AT: survey design, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation. RC: project concept, survey design, data interpretation, and manuscript preparation.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2019.19.