Introduction

Hockey is a popular sport played by First Nations (includes status and non-status Indians) youth in Ontario. Reports have shown that at least one in ten youth (6-18 years) will suffer a concussion while playing ice hockey in Canada.Reference Benson, Hamilton, Meeuwisse, McCrory and Dvorak 1 Young athletes are more susceptible to concussion due to larger head to body size ratio, weaker neck muscles and increased vulnerability of the developing brain.Reference Sim, Terryberry-Spohr and Wilson 2 Differences in the physical size of young hockey players can also contribute to the risk of concussion.Reference Cusimano, Taback, McFaull, Hodgins, Bekele and Elfeki 3 Even minor concussions in hockey are serious injuries for youth.Reference Laurer, Bareyre and Lee 4 They have the potential to lead to a second impact syndrome which can result in severe neurological deficits and even death.Reference McCrory, Davis and Makdissi 5 Youth take longer to recover from a concussion compared to adults. Furthermore, an estimated 21%-73% of young patients who experience a concussion may develop post-concussive syndrome.Reference Babcock, Byczkowski, Wade, Ho, Mookerjee and Bazarian 6 - Reference Ellis, Ritchie and McDonald 8 Post-concussive syndrome is defined as at least one symptom for at least 4 weeks and can result in a heterogeneous population of youth with chronic disability requiring costly and multidisciplinary intervention.Reference Ellis, Ritchie and McDonald 8 - Reference Tator 12 Post-concussive syndrome can impact a youth’s education, future employability and ability to integrate within their community.Reference Williams, Rapport, Millis and Hanks 13 It can contribute to depression, substance abuse and suicide.Reference Bryant, O’donnell, Creamer, McFarlane, Clark and Silove 14 , Reference Lukow, Godwin, Marwitz, Mills, Hsu and Kreutzer 15 Aspects of hockey culture can place an overemphasis on winning games. The lack of understanding and misperceptions about health risks associated with concussion have all been identified as reasons that concussions go unrecognized, unreported and unmanaged in youth hockey.Reference Cusimano, Topolovec-Vranic, Zhang, Mullen, Wong and Ilie 16

Unintentional injuries among Indigenous (First Nations, Inuit and Metis) youth occur at rates three to four times the national Canadian average.Reference Banerji 17 Striking health inequities result from many factors, such as reduced access to medical and rehabilitation services, lack of sport safety equipmentReference Zeiler and Zeiler 18 and lack of safety education.Reference Ross, Dion, Cantinotti, Collin-Vézina and Paquette 19 Only two articlesReference Blackmer and Marshall 20 , Reference Dudley, Feyz, Maleki and Marcoux 21 were identified in a recent literature review of studies on traumatic brain injury in North American Indigenous populations.Reference Zeiler and Zeiler 18 These early calls to action for Indigenous brain injury prevention have been unrequited. There is growing public health concern over the vulnerability of the developing brain to injury,Reference Ellis, Ritchie and McDonald 8 the long-term consequencesReference Hiploylee, Dufort and Davis 11 , Reference Manley, Gardner and Schneider 22 and high costsReference Hunt, Zanetti and Kirkham 23 of sport-related concussion injuries.Reference Ellis, Ritchie and McDonald 8 , Reference McCrory, Meeuwisse and Dvorak 24

Concussions may occur subtly during hockey and are often difficult for even trained coaches to identify.Reference McCrory, Meeuwisse and Aubry 25 At present, there is no single validated tool to diagnose a concussion or to determine when a player should return to play.Reference McCrory, Meeuwisse and Aubry 25 Subjective symptom reporting is essential to identify and limit neurological trauma.Reference Marar, McIlvain, Fields and Comstock 26 Young athletes have been shown to underreport between 50%-75% of concussions.Reference Register-Mihalik, Guskiewicz, McLeod, Linnan, Mueller and Marshall 27 Evidence has demonstrated that improved knowledge of concussion among youth can lead to improved concussion symptom reporting.Reference Register-Mihalik, Guskiewicz, McLeod, Linnan, Mueller and Marshall 27 Parents also play an important role in the identification of concussion symptoms in youth and in managing their at home recovery.Reference Lin, Salzman and Bachman 28 , Reference Stevens, Penprase, Kepros and Dunneback 29 In cases where medical professionals are not available to manage concussion, coaches are often left in the position of managing both the concussed athlete and the game.Reference Guilmette, Malia and McQuiggan 30 Therefore, ensuring coaches have sound knowledge of concussion is also important. The objective of this study was to investigate knowledge, attitudes and sources of information about concussion among young recreational hockey players, parents and coaches participating in a 3-day provincial First Nations hockey tournament in Ontario.

Methods

Ethics, Study Design and Study Population

This study was conducted in collaboration with First Nations partners which included Serpent River First Nations, Union of Ontario Indians and the Little Native Hockey League (LNHL). Ethical approval was received from the Chief and Band Council of the Serpent River First Nations, the LNHL organization and the St. Michael’s Hospital Institutional Review Ethics Board. The research study was conducted within the First Nations principles of ownership, controlled access and possession. 31

Data collection was by the administration of a cross-sectional survey during the annual provincial hockey tournament. Participants were invited to sit at a table to complete the paper and pencil survey. All study participants had the opportunity to enter a draw for an i-PAD by submitting ballots separate from the questionnaire.

Approximately 80 First Nations youth hockey teams from across Ontario competed in the three day tournament with parents, relatives and community members in attendance. Study recruitment posters were placed on the hockey tournament web site in advance. A total of 391 participants completed the study questionnaire. Three participant groups were selected for comparisons, players (n=75), coaches (n=68) and parents (n=248). Players were aged 6-18 years and competing in the tournament. Coaches included team managers, hockey officials and referees. The parent category included family members and other community members aged 19 years and older. If a parent was also a coach they were classified as “coach”, as coaches usually receive first aid training.

Survey Tool

The survey instrument published by Mrazik et al.Reference Mrazik, Perra, Brooks and Naidu 32 was selected with modifications undertaken. The number of questions from the published survey was reduced in order to provide a brief tool suitable for players, parents and coaches to complete within a 10-minute time frame. The study team decided that this time frame would be suitable to the study setting of a busy arena during a hockey tournament. The tool had four sections all with a multiple choice format. The first section consisted of five knowledge questions. Three of the five questions addressed recognition of concussion, return to play and frequency of concussion in young recreational hockey players (questions 2,7,9).Reference Mrazik, Perra, Brooks and Naidu 32 The study team added two new questions regarding length of symptoms and return to school (see Appendix). The second section of the tool addressed symptom recognition. It consisted of a list of ten symptoms (eight concussion symptoms and two distractors (question 12).Reference Mrazik, Perra, Brooks and Naidu 32 The third section of the survey had three attitude questions regarding seriousness, likelihood of and worry about a concussion in hockey (questions 8, 10, 11).Reference Mrazik, Perra, Brooks and Naidu 32 Minor wording changes of the study instrument included changing, “If you were to play hockey how likely is a concussion” to “If you/your child/a child you know were to play hockey how likely is it that you/your child/a child you know could get a concussion”. The fourth section of the survey consisted of one question whereby participants selected their sources of concussion information from a list of eight possible sources. Data on demographics (gender and closest city to their residence) and history of concussion(s)(see appendix) were also collected.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was total knowledge index, scored out of 15 points. It was derived from the sum of correct responses to the knowledge questions (5) added to the symptom scores (total of ten points; eight for correct symptoms and two points for the correct identification of distractors). In addition, a mean total knowledge score (MTKS) (used in Table 4) was also calculated and consisted of the sum of correct knowledge and correct symptoms only (excluding the distractors) resulting in a total possible score of 13. A higher score indicated greater understanding of the risk and significance of concussion.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequency, proportions, means and standard deviations) were performed (see Table 1). χ 2 tests were used for between group comparisons of individual items in the survey. Analysis of variance with post hoc analysis was used to compare general knowledge score, symptom knowledge score and total knowledge index by group. Percentages of players, parents and coaches using various sources of information about concussion were compared using a Z test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.

Table 1 Characteristics of participants by study group

Results

Study Participants

Study participants resided in Ontario with almost half from northern regions, one-third from the central Toronto region and fewer from the southwest region of Ontario. Females represented 80% of parents, 61% of players and 47% of coaches. Results showed a statistically significant differences in gender between players and parents (χ 2=16.786, p=0.001) and between coaches and parents (χ 2=27.595, p=0.001). Differences between players and coaches by gender was not significant (χ 2=1.217, p=0.270).

Among coaches 49% reported previous concussion(s), in contrast to 23% of the players and 26% of the parents. For those with previous concussions, three or more was reported by 24% of the coaches, 7% of players and 6% parents of parents. There was a significant difference in previous concussions between players and coaches (χ 2=9.199, p=0.002) and coaches and parents (χ 2=9.705, p=0.002). Findings between players and parents for previous concussion(s) was not statistically significant (χ 2=0.456, p=0.499).

Knowledge

Frequencies and percentages of correct knowledge questions, knowledge and symptoms scores, and total knowledge index are summarized in Table 2. Study participants demonstrated a good understanding of two of the five knowledge items, with recognition of concussion and return to school, receiving the greatest number of correct responses. The length of the duration of concussion symptoms was underestimated, with players having the fewest number of correct responses (players 9.3%, parents 22.6%, coaches 30.9%). Prevalence of concussion in hockey was also misunderstood. Players again had the fewest number of correct responses (players 14.7%, parents 26.6% and coaches 30.9%). The question referring to when a hockey player should return to play had few correct responses (players 18.7%, parents 19.4% and coaches 23.5%). The mean knowledge scores were as follows; for players 1.9/5, parents 2.2/5 and coaches 2.5/5. Differences in knowledge scores amongst the three groups were statistically significant (F (2,388)=6.173, p=0.002). Mean concussion symptom knowledge scores were also low (players 4/10, coaches 5.3/10, parents 5.5/10). Differences in mean symptom knowledge scores between players and coaches as well as between players and parents were statistically significant (F (2,388)=10.167, p=0.001). Differences in symptom scores between coaches and parents were not significant. Finally, the total knowledge index by group was as follows: players 5.9/15, parents 7.5/15 and coaches 7.8/15. Differences in total knowledge index between players and coaches and between players and parents were statistically significant (F (2,388)=12.643, p=0.000).

Table 2 Hockey scores, symptom scores and total knowledge index by study group

*p<0.05; **p<0.001.

History of Concussion

Table 3 reports concussion history by study group, mean knowledge scores, symptom sub-scores and total knowledge index. In all categories, mean sub-scores were higher among participants with a history of concussion, with the exception of knowledge scores for parents.

Table 3 Hockey, symptom and total knowledge index by previous concussion and group

TBI=traumatic brain injury

Attitudes

Table 4 displays the MTKSs for each response to the attitude questions. A significant statistical difference across study groups on all attitude questions emerged. When asked how serious they perceived a concussion, among players with the highest MTKS (7.0/13), 46.7% selected the “more serious”. Parents with the highest MTKS (7.8/13), 57.7% also selected “more serious”. Whereas, coaches with the highest MTKS (8/13) a total of 32.8% reported “as serious”. Regarding likelihood of concussion, players with the highest MTKS (6.8/13), 25 % claimed “likely”. Among parents with the highest MTKS (7.8/13), 40.9% selected “likely”. However, coaches with the highest MTKS (8.2/13), at total of 49.3% selected “somewhat likely”. Finally, when asked how worried are you or your child about getting a concussion this year, players with the highest MTKS (6.5/13), 8% were “very worried”. Coaches with the highest MTKS (8.5/13), 35.3% worried “a little bit”. Among parents with the highest MTKS (7.8/13) a total of 43.5% also worried “a little bit”.

Table 4 Attitudes of participant groups with responses by mean total knowledge scores

*p<0.05 (maximum total knowledge score=13).

Sources of Information About Concussion

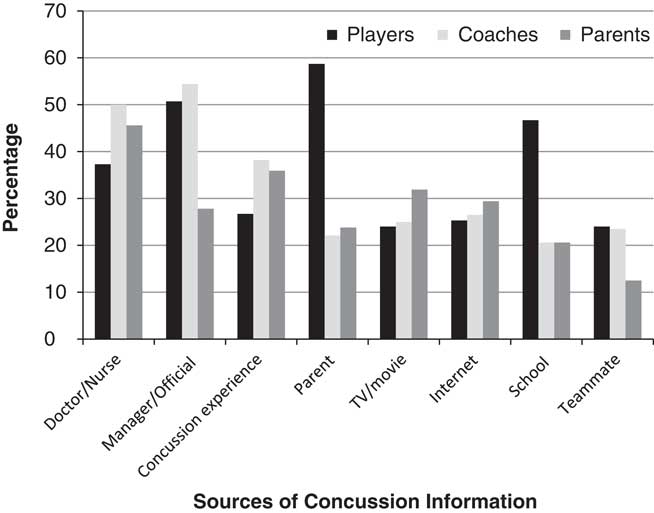

Players, coaches and parents identified multiple sources of information about concussion as illustrated in Figure 1. The greatest proportion of players identified parents/guardian (58.7%), while most coaches identified coaches/managers/officials (54.4%). The majority of parents identified doctor/nurse (45.6%). Players and coaches were significantly more likely than parents to report they had gained information from coach/manager/officials (χ 2=23.856, p=0.000). Players were significantly more likely than coaches and parents to gain information from parents (χ 2=35.817, p=0.000). Players were significantly more likely than coaches or parents to gain information from school/teachers/work (χ 2=21.688, p=0.000). Players and coaches were significantly more likely than parents to acquire information from a teammate/friend (χ 2=8.326, p=0.016).

Figure 1 Sources of concussion information by players, coaches and parents.

Discussion

A convenience sample of First Nations people attending a 3-day youth hockey tournament completed a short survey about concussion. The proportion of correct responses were compared across three study groups, players (n=75), parents (n=248) and coaches (n=68). The study is believed to be one of the first to investigate First Nations knowledge, attitudes and sources of information about concussion in collaboration with Indigenous peoples from Ontario.

Knowledge and Attitudes

Mean knowledge index scores by study group were coaches 7.9/15 (52.6 %), parents 7.5/15 (50%) and players 5.9/15 (39.3%). For players and coaches with a history of a concussion, knowledge scores were higher. This was also true for parents however, knowledge scores improved minimally for those with a history of concussion. Other research examining parental knowledge of concussion supports our findings of knowledge deficits even among parents who had experienced their own concussion.Reference Lin, Salzman and Bachman 28 , Reference Stevens, Penprase, Kepros and Dunneback 29 Players with the lowest knowledge scores demonstrated the most concerning attitudes, feeling concussion was “unlikely” and being “not at all worried” about a concussion while playing hockey. As the tournament took place at the end of the hockey season perhaps concussion knowledge that might have been provided earlier in the season was waning. However, other studies investigating non-Indigenous youth athletes reported low knowledge levels regarding symptoms and dangers of concussion even when pre-season education had occurred.Reference Mrazik, Perra, Brooks and Naidu 32 , Reference Anderson, Gittelman, Mann, Cyriac and Pomerantz 33 Our findings support other Canadian reports from non-Indigenous populations, where youth reported misunderstandings of symptom duration and safety.Reference Cusimano, Topolovec-Vranic, Zhang, Mullen, Wong and Ilie 16 , Reference McCrory, Meeuwisse and Dvorak 24 , Reference Cusimano, Nastis and Zuccaro 34 These are important findings as misunderstandings and lack of knowledge can lead to dangerous health outcomes for youth playing hockey. Misconceptions about concussion by parents and coaches may lead to poor information being passed down to youth. Studies have shown younger players compared to older players demonstrated less perception of vulnerability while playing hockey.Reference Mrazik, Perra, Brooks and Naidu 32 These findings further highlight the urgency of concussion education for First Nations players, coaches and parents. The influences and teachings of parents, family and elders are of upmost importance to learning for Indigenous youth and these community members will have to be consulted in the planning of any interventions.Reference Ross, Dion, Cantinotti, Collin-Vézina and Paquette 19

Studies among non-indigenous populations have identified approaches to prevention and education that may offer insights for Indigenous communities. For example, the use of protective equipment in hockey including helmets, mouthguards and neckguardsReference Benson, Hamilton, Meeuwisse, McCrory and Dvorak 1 , Reference Cusimano, Nastis and Zuccaro 34 is not always available for Indigenous youth. Programs to provide proper hockey equipment to Indigenous youth are immediately needed. Pre-season physical activity and training including conditioning of the neck muscles may also be helpful to prevent a concussion.Reference Emery, Black and Kolstad 9 , Reference Tator 12 Education provided to players, parents and coaches can be augmented through web-based education and videos such as Parachute 36 and the CATT program from British Columbia. 35 Others advocate for “concussion road shows”,Reference Tator 12 which would be well suited for the large LNHL hockey tournament. Bringing concussion education through invited speakers such as nurses, physicians, media and hockey personalities to a wide tournament audience could benefit attendees. Pre-season hockey team meetings and locker room posters urging players to report concussion are other supportive educational strategies.Reference Tator 12 Improving coach approachability and communication of coaches with youth could also be helpful.Reference Kroshus, Garnett, Hawrilenko, Baugh and Calzo 39 Fair play rules and enforcement to reduce and eliminate body checking can also be promoted.Reference Cusimano, Nastis and Zuccaro 34 Fair play rules can also reward teams for not committing fouls in hockey.Reference Cusimano, Nastis and Zuccaro 34 Finally, sport-specific and hockey player position-specific strategies may also play an important role in concussion awareness and prevention.Reference Emery, Black and Kolstad 9 However, it is worth noting that many of these strategies require further evaluation to validate their preventative effectiveness.

Call for Cultural Safety in Concussion Knowledge Translation for Indigenous Populations

Cultural factors can also play an important role in the uptake and maintenance of injury prevention strategies.Reference Emery, Black and Kolstad 9 , Reference Banerji 17 , Reference Ross, Dion, Cantinotti, Collin-Vézina and Paquette 19 A growing body of evidence has described the importance of education programs for reducing injury rates in youth hockey.Reference Cusimano, Nastis and Zuccaro 34 Study participants reported receiving information about concussion from a wide variety of sources. Our findings suggest that both sports-based and school-based programs could effectively reach a wide Indigenous audience. However, the educational training that the individuals presenting these programs may have received is not well known. Only recently in Canada have programs targeted to parents and coaches been more clearly defined in their content and been readily available. 35 , 36

Other educational programs continue to be developed and implemented with no record or requirements for safety content.Reference Eagles, Bradbury-Squires, Powell, Murphy, Campbell and Maroun 37 In our study half of all participants reported receiving concussion information from a nurse or doctor. Even among health care professionals standardized knowledge translation for concussion has not been established.Reference Ellis, Ritchie and McDonald 8 , Reference Burke, Chundamala and Tator 38 The Canadian federal government in collaboration with the Public Health Agency of Canada, Parachute Canada and the National Sport Organizations have recently released the Canadian Guideline for Concussion in Sport that include pre-season education for all stakeholders. This could be a valuable resource that may need to be adapted for First Nations populations.

Many Indigenous youth have not benefitted to the same degree as other Canadian youth from safety campaigns such as car seats, seat belts, swimming lessons and first aid training.Reference Kroshus, Garnett, Hawrilenko, Baugh and Calzo 39 , Reference Harrop, Brant, Ghalo and Macarthur 40 The lack of culturally appropriate and targeted prevention programs for Indigenous youth is a barrier to knowledge and to the ability to reduce injury rates through education.Reference Banerji 17 Concussion education strategies should be adapted to the local context.Reference Emery, Black and Kolstad 9 Community is known to be extremely important and connected to health and wellness in the Indigenous population.Reference King, Smith and Gracey 41 Concussion awareness interventions should be culturally guided and focused on collaboration with community organizations.Reference Zeiler and Zeiler 18 Collaboration with elders and respected community members such as coaches can help. A cultural safety approach to education and prevention is needed to fit the target groups of players, parents and coaches within the Indigenous world views and social, economic and political context in determining actionable strategies to support the reduction of injuries.Reference Giles, Hognestad and Brooks 42 , 43 Culturally safe health strategies for Indigenous youth can help them to share their perspective on pain.Reference Latimer, Finley and Rudderham 44

Study Limitations

This study had several limitations. Study participants were a convenience sample not a random group. Individuals self-selected into the survey group and their decisions to complete may have been influenced by their concussion awareness. As no definition of a concussion was provided, participants may not have met standard definitions for having previously sustained a concussion. Despite asking subjects to be truthful in their responses, the excitement of the hockey tournament and presence of peers and parents may have influenced responses toward those that were socially desirable. Concussion history relied on self-reports and may not represent what might have happened in “real-life situations”.Reference Anderson, Gittelman, Mann, Cyriac and Pomerantz 33 In addition responses may have also been susceptible to recall bias.Reference Iverson, Lange, Brooks and Rennison 45 The First Nations tournament does not allow body checking so participants reporting previous concussions may be a result of other sports, activities or events. The survey instrument by Mzaik et al.Reference Mrazik, Perra, Brooks and Naidu 32 was not developed for adults. The modifications undertaken for this study may have impacted instrument validity.

Future studies should investigate whether higher levels of concussion knowledge and higher attitudes toward the severity of concussion influence behavior on the ice, the number of concussions experienced and symptom reporting.Reference Eagles, Bradbury-Squires, Powell, Murphy, Campbell and Maroun 37 Further examination of First Nations players, parents and coaches attitudes toward concussion may also be helpful to improve understanding and to inform future concussion awareness and prevention strategies. Examining the quality of concussion health care available to First Nations communities also warrants further study.

Conclusions

This study raises concern about concussion knowledge, symptom awareness and attitudes about concussion among First Nations youth who play hockey, as well as their coaches and parents. Encouraging First Nations youth to participate in hockey must be accompanied by activities to educate about and to prevent concussion. Immediate attention is required to adopt an Indigenous lens to build culturally safe approaches to any intervention.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rishothan Yogananthan, Raiyan Chowdhury and Rachel Chin for their contribution to this project. The authors also thank the First Nations study participants who completed the survey.

Disclosure

CH, AM, CL, LM, TJ and DO do not have anything to disclose.

Appendix

How long do you think symptoms of concussion can last?

a) 10 days

b) 10 months

c) 2 years

d) 5 years

When do you think a child or teen can go back to school after a concussion?

a) Next day

b) Half days

c) Every brain heals differently so you will need to discuss with the health care provider

d) A week

Have you ever suffered a concussion or blow to the head or body that caused you to be dazed or confused?

□ Yes, If yes, how many times has this happened to you ___

□ No, I have never suffered a concussion