Thank you for the opportunity to respond to the letter by Aileen McGonigal and Jean-Arthur Micoulaud-Franchi.Reference McGonigal and Micoulaud-Franchi 1 We were delighted to see that our publication “Anxiety and Depression in Adult First Seizure Presentations” elicited such interest from another group.Reference Lane, Crocker, Legg, Borden and Pohlmann-Eden 2 In their letter to the editor, the authors point out a concern that our choice of 14 as a cutoff score on the general anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) may have resulted in some cases of anxiety not being screened in by the instrument. We welcome these comments and herein explain in more detail our choice of 14 as a cutoff and also present a re-analysis of the GAD-7 data using a cutoff of 10.Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe 3 , Reference Kroenke, Spitzer, Williams, Monahan and Lowe 4

Screening instruments for mental health disorders are a useful starting point in a non-psychiatric patient population. When choosing a screening tool for use in any patient population, there needs to be a balance between high sensitivity and negative predictive value and between specificity and positive predictive value. In addition, these statistical measurements are based on validation in the original study population and may have different results when applied to different study populations. In our study, early intervention services, such as a First Seizure Clinic, are particularly challenging environments to measure depression and anxiety. These are patients who often have not had much previous contact with the healthcare system and are naturally worried about a potential diagnosis of epilepsy.Reference Devlin and Arneill 5 In this unique setting, patients can experience increased anxiety upon presentation to clinic. It was this setting that led to our choice of a cutoff value that had a higher specificity to try and capture those patients with severe anxiety who were more likely to benefit from a referral to psychological testing and counseling.

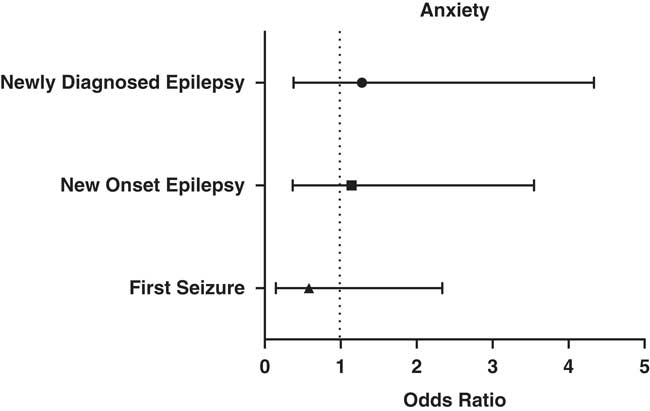

The responses from the GAD-7 from the original study were re-analyzed with χ 2 odd’s ratios for control versus unprovoked seizure patients for a new cutoff value of 10. The results are shown in Figure 1, and they do not differ trend-wise from what we saw in the initial study with a cutoff value of 14. The revised analysis gave an odds ratio (OR) of 0.58 (95% confidence interval [CI]=0.14-2.33) for the first seizure-only patient group; an OR of 1.14 (95% CI=0.36-3.55) for new-onset epilepsy patients; and an OR of 1.28 (95% CI=0.38-4.34) for the newly diagnosed patients (seizure history of greater than 12 months duration). There is a significant linear trend (p=0.038) between subgroups with this cutoff. This raises the possibility that anxiety is increasing over time with duration of disease, which would be in keeping with our findings regarding our depression screening.Reference Lane, Crocker, Legg, Borden and Pohlmann-Eden 2

Figure 1 Odd’s ratio of anxiety measure for First Seizure, New Onset Epilepsy (seizures less than 12 months duration), and Newly Diagnosed Epilepsy (seizures greater than 12 months duration but previously undiagnosed as such).

Interestingly, the increase in the cutoff value for the GAD-7 led to more control individuals meeting criteria, but there was still no statistical difference between control and patient groups. Our selection criteria for control participants excluded blood relatives of the patient to the clinic, but healthy control participants were individuals who did not have a diagnosed psychiatric disorder and were accompanying patients to clinic. We chose this arrangement to try and control for the anxiety of the hospital environment. The anxiety of attending a hospital appointment can extend to those who accompany patients to clinic, particularly caregivers and family members,Reference Jones and Reilly 6 , Reference van Andel, Westerhuis, Zijlmans, Fischer and Leijten 7 and served as our control group. This may have affected the levels of anxiety of our control group. There is also the possibility of an undiagnosed anxiety disorder in these individuals, but that seems less likely.

We appreciate the thoughtful feedback from our colleagues. Completing this second analysis confirms the results, and we remain confident that our initial approach, that is, using the lower cutoff criteria of 10 for the GAD-7, did not significantly change the conclusions from our study. We feel that we should continue to emphasize that although screening questionnaires are helpful tools in quantifying psychiatric co-morbidities they are not a replacement for a full psychiatric assessment. This suggests that the presence of a psychiatric condition, and in particular depression, may precede the onset of a seizure disorder in this clinic population. We therefore theorize that recognizing psychiatric co-morbidities at an early stage of epilepsy may increasingly play a role in identifying subtle biomarkers for underlying epileptogenesis. This is an area that we hope to continue to explore in our research.

Disclosure

CC reports grants from Epilepsy Association of Nova Scotia, during the conduct of the study. BPE received funding for the study by a grant from Epilepsy Association Nova Scotia. CL, MB, and KL have nothing to disclose.