We wish to report the case of a patient whom we have been following for years for Parkinson’s disease (PD) who recently committed suicide. Our objectives are twofold: 1) to raise awareness about the sad reality of suicide in PD and 2) to discuss the possible role that dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome (DAWS) might have played in this tragedy.

Nazem et al. discovered that death by suicide and suicidal ideation may be found in as many as 30% of PD patients, with a 4% lifetime suicide attempt.Reference Nazem, Siderowf and Duda1 That study identified the presence of depression and impulse control disorder (ICD) as risk factors for both death and suicidal ideation,Reference Nazem, Siderowf and Duda1 whereas depression, but not ICDs, was identified as a risk factor for both ideations in another study.Reference Kostic, Pekmezovic and Tomic2

A 42-year-old gentleman was diagnosed with PD. His symptoms at the onset consisted of right-sided bradykinesia and rigidity. We initiated treatment with rotigotine patch 2 mg/24 h, which was later increased to 4 mg/24 h. Four years after symptom onset, he started to notice worsening of his motor activities, which led him to develop considerable anxiety issues, for which he was started on venlafaxine, titrated up to 150 mg daily over a few months. His rotigotine patch was also progressively increased to 8 mg/24 h, as he was experiencing increased difficulty using his right side. Levodopa/carbidopa (levocarb) was also started and titrated up to 100/25 mg three times a day. About 1 year later, he reported that he was experiencing symptoms of ICD, including gambling, excessive spending, compulsive masturbation, and pornography addiction, which strained his marriage and eventually led to a divorce. Of note, the patient did not have a psychiatric history prior to the events reported here.

To address the ICD, rotigotine was decreased to 6 mg/24 h, without improvement of the ICD symptoms and was then further diminished to 4 mg/24 h and then to 2 mg/24 h, 4 and 8 months later, respectively. Whereas the ICD subsided slightly on this lower dose of rotigotine, he began experiencing apathy, lack of energy, fatigue, irritability, and anxiety. In addition, the decrease of rotigotine led to a deterioration of his parkinsonism, for which levocarb was increased up to 100/25 mg 1.5 pill four times daily and rasagiline 1 mg daily was introduced, with subsequent improvement of parkinsonism but no effect on the non-motor manifestations reported above, which probably represented a DAWS. He simultaneously suffered from erectile dysfunction, possibly related to the venlafaxine, although it might also have been related to dysautonomia secondary to PD. Nevertheless, venlafaxine was progressively discontinued and replaced by bupropion 300 mg daily. As the apathy remained, vortioxetine, up to 10 mg daily, was added later. Despite this pharmacotherapy and our psycho-social support, he began experiencing suicidal thoughts, and eventually decided to end his life.

Reflecting on the complexity of this case, we acknowledge that it is difficult to pinpoint a single factor that led our patient to commit suicide. However, it appears that high dose rotigotine, leading to the development of an ICD, triggered a cascade of manifestations that left us struggling to adequately address all of the reported symptoms. Indeed, our patient developed an ICD that had important repercussions in his personal life, leading us to progressively reduce the dose of his dopamine agonist, which in turn led to a probable DAWS. Indeed, we note that the patient described here presented several of the clinical features of DAWS, e.g., anxiety, depressive symptoms, irritability, etc.Reference Yu and Fernandez3 However, it is important to point out that dopamine agonists, especially pramipexole, might be effective agents to treat depressive features in PDReference Seppi, Ray Chaudhuri and Coelho4 and that the reduction of rotigotine may therefore have unmasked a depression. We acknowledge that this diagnostic conundrum warrants caution in the interpretation of the case presented here. To mitigate this possibility, a trial of reintroducing higher doses of rotigotine might have been performed, but we elected not to do it, as severe ICD had developed on higher doses.

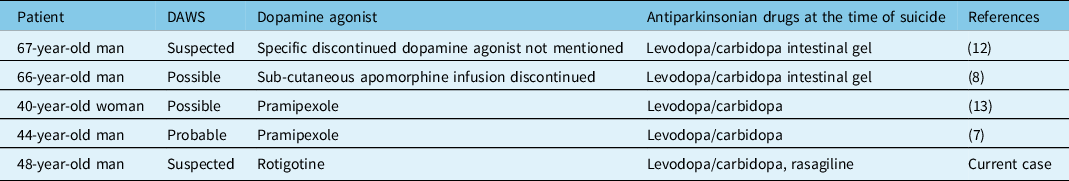

DAWS is a condition that remains relatively poorly understood, despite being increasingly recognised, and consists of symptoms reminiscent of addictive drug withdrawal,Reference Chaudhuri, Todorova and Nirenberg5 which may last for several years.Reference Yu and Fernandez3,Reference Huynh, Sid-Otmane, Panisset and Huot6 A previous case reported a PD patient committing suicide after discontinuation of the dopamine agonist pramipexole because of severe ICD.Reference Flament, Loas, Godefroy and Krystkowiak7 Another case described a PD patient committing suicide while on levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel infusion; we note that apomorphine infusion had been discontinued a few months before he ended his life.Reference Santos-Garcia, Macias, Llaneza and Aneiros8 DAWS was also suggested to be a cause of suicide in a patient treated with levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel infusion whose dopamine agonist had been discontinued shortly before he committed suicide.Reference Solla, Fasano, Cannas and Marrosu9 A summary of cases of PD patients who committed suicide possibly because of DAWS, including our case, is presented in Table 1. Lastly, a dopamine withdrawal state was proposed to underlie suicidal attempts that may be committed after deep-brain stimulation surgeries.Reference Voon, Krack and Lang10,Reference Thobois, Ardouin and Lhommee11

Table 1: Reported cases of DAWS and suicide in patients with PD

DAWS: dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome.

In summary, we have reported the case of a man with early onset PD who committed suicide after reducing the dose of rotigotine he was on because of ICD, after which he seemingly developed a DAWS. We acknowledge that it is impossible to pinpoint a single cause that would have led him to end his life, yet we wish to highlight that DAWS might be a possible factor in this case. We would also like to emphasise that DAWS might be particularly challenging to treat, here it did not abate despite therapy with levocarb, rasagiline, and anti-depressants, coupled with a low dose of rotigotine. Reflecting further on the case, perhaps we could have attempted to slightly increase the dose of rotigotine, to achieve a delicate balance between ICD and DAWS, but at the time we were reluctant to do so, as we felt the previous ICD already had too great of an impact on our patient’s life, notably leading to a divorce. Retrospectively, it might have been worth trying, with tight follow-up appointments.

We hope that this case will be helpful to clinicians when they consider beginning a dopamine agonist to treat PD, and also when they deem it necessary to reduce the dose, as a dose reduction may be poorly tolerated, difficult to manage, and lead to dire consequences.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the personnel of the McGill University Health Centre Movement Disorder Clinic, in this case to Mr Pascal Girard and Ms Lucie Lachance, for their dedication to the well-being of the patients, their great empathy, and limitless compassion.

Funding

CK has held a scholarship from Parkinson Canada and holds a scholarship from Fonds de Recherche Québec – Santé. PH has had research support from Parkinson Canada, Fonds de Recherche Québec – Santé, Parkinson Québec, Healthy Brains for Healthy Lives, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and the Weston Brain Institute. PH has received payments and consultancy fees from Neurodiem, Throughline Strategy, Sanford Burnham Prebys, AbbVie, Sunovion, and adMare BioInnovations.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Statement of Authorship

CK, TK, and PH each contributed to the writing of this manuscript.