Introduction

Low back pain and neck pain are common causes of disability worldwide. Reference Manchikanti, Singh, Falco, Benyamin and Hirsch1,Reference Cohen2 In Canada, the prevalence of low back pain is reported as high as 84%. Reference Gross, Ferrari and Russell3 Most cases are successfully treated with a conservative approach, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine is only recommended when serious pathologies are suspected. 4,Reference Chou, Qaseem, Owens and Shekelle5 The Canadian Association of Radiologists and the College of Family Physicians of Canada have, through a Choosing Wisely campaign, suggested to order lumbar spine MRI only in the presence of so-called red flags. 6,7 In 2017, the Institut National d’Excellence en Santé et Services Sociaux (INESSS) of Québec published an interactive tool to improve the appropriateness of MRI use for low back pain and neck pain. 8

Few studies have been published about the proportion of appropriate spine MRIs. Thirty-one percent of lumbar spine MRIs were classified as inappropriate in a Veterans Health Administration of the USA study and 10.6% in a prospective multicentric study from Spain. Reference Kovacs, Arana and Royuela9,Reference Gidwani, Sinnott, Avoundjian, Lo, Asch and Barnett10 Evidence of inappropriate use of spine MRI in Canada is sparse. A Canadian systemic review published in 2015 concluded that the actual proportion of inappropriate MRIs was not yet established. Reference Vanderby, Peña-Sánchez, Kalra and Babyn11

We hypothesized that there is over-ordering of lumbar and cervical spine MRIs despite INESSS recommendations. To our knowledge, there is no published study in Canada about the appropriateness of MRI for low back pain and neck pain based on empirical evidence. In this retrospective observational study, based on the INESSS guide 8 , we stratified the appropriateness of MRI requests of all patients evaluated for low back pain and neck pain during 3 months in the electromyography (EMG) clinic of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke (CHUS). The primary objective was to describe the proportion of appropriate, possibly appropriate, and inappropriate MRI requests. The secondary objective was to compare the proportion of appropriateness MRI requests with data collected only from MRI requests versus data collected from MRI requests and EMG consultation reports.

Methods

This is a retrospective observational study realized in the EMG clinic in CHUS, a tertiary hospital in Quebec, Canada. This study was approved by the ethics review board of CHUS. All cases of low back pain or neck pain who have had an EMG evaluation between March 1, 2018, and May 31, 2018, and a request of lumbar and/or cervical spine MRI were recruited. IRM requests ordered before and after EMG were included. No cases of IRM request alone without EMG evaluation were included.

All ambulatory patients 18 years or older were included. All demographic and red flags variables were collected from EMG consultation reports and MRI requests and included age, gender, location of MRI (CHUS or exterior center), previous imaging (X-ray, computed tomography scan (CT-Scan), or scintigraphy), specialty of physicians who ordered MRI, date of initial symptoms, date of MRI ordering, pertinent past medical history (neoplasia, trauma, spine surgery, osteoporosis, immunosuppression, prolonged use of corticosteroid, intravenous drug use, and recent infection), the clinical suspicion of cauda equina syndrome, spinal stenosis or spondyloarthropathy, the presence of fever of unknown cause, unexplained weight loss, progressive motor radiculopathy, or failure of conservative treatment. Failure of conservative treatment was defined as no improvement of pain after 6 weeks of pain medication and inability to get back to normal activity with or without physiotherapy.

MRI requests were classified as appropriate, possibly appropriate, and inappropriate according to the interactive decision support guide of INESSS for optimal use of MRI in the case of musculoskeletal pain in adults. 8 Appropriate MRI included low back pain or neck pain with suspicion of tumoral or infectious causes by the presence of red flags (history of neoplasia, unexplained weight loss, immunosuppression, failure of conservative treatment, intravenous drug use, fever of unknown cause, or recent infection); spine trauma with neurologic deficits after X-ray or CT-scan; suspicion of cauda equina syndrome or compressive myelopathy; and the presence of progressive motor radiculopathies. Possibly appropriate MRI included low back pain or neck pain with radiculopathy or spinal stenosis, failure of conservative treatment, and candidates for surgery or infiltration; history of spine surgery; low back pain with risk of fractures after X-ray, chronic low back pain with suspicion of spondyloarthropathy; and spine trauma without neurologic sign after radiography or CT-scan. Inappropriate MRI included acute low back pain with or without painful sensory radiculopathy and no sign of serious pathology, subacute or chronic lumbar pain without complications and no sign of serious pathology, and neck pain without neurologic signs and no suspicion of serious pathology.

A subgroup of MRIs ordered in the first 90 days of symptoms was also analyzed to minimize recall bias. The analyses of the secondary objective were not possible because most MRI requests lack essential information for classification like red flags and date of initial symptoms. All statistics were obtained with SPSS version 25.

Results

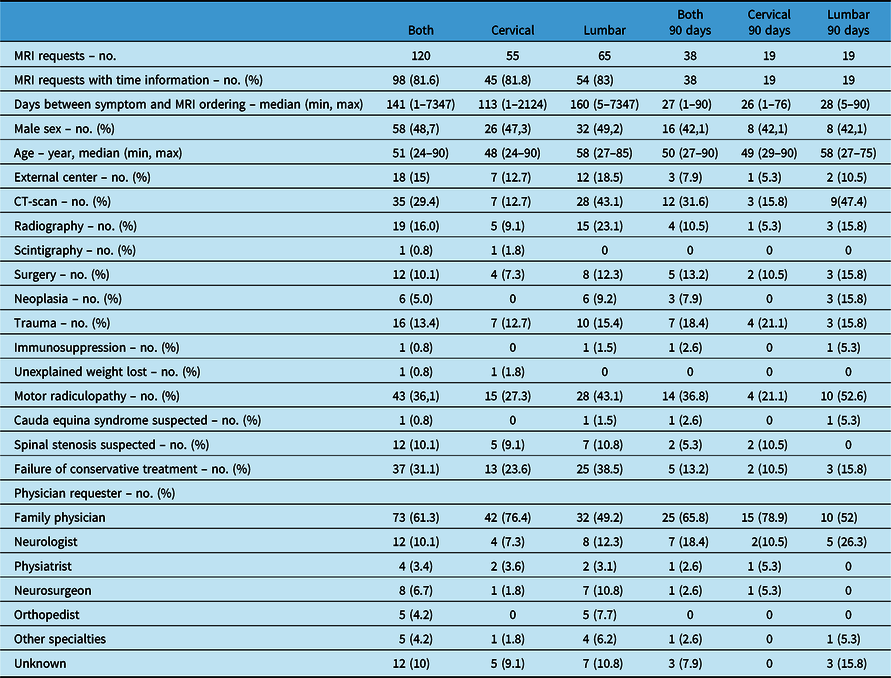

One hundred and twenty MRI requests, 55 cervical spines and 65 lumbar spines, were analyzed from 119 EMG consultations. One patient had both cervical and lumbar MRI requests. Demographic information is summarized in Table 1. The median (Min, Max) age was 51 years (24–90); patients with cervicalgia were slightly younger (48 years (24–90)) than patients with lumbar pain (58 years (27–85)). Sex distribution was well balanced (48.7% male). The median duration between initial symptoms and MRI ordering was 141 days (1–7347) and in the subgroup of MRI ordered in the first 90 days of onset, the median of days was 27 (1–90). In 21 cases, we did not have time interval, mostly because MRIs were done in external centers. The most frequent prior imaging was spine CT-scan (35 cases; 29.4%) and mostly in the lumbar group (28 cases; 43.1%). Twelve patients (10.1%) had a prior surgery of the same spinal segment. Forty-three patients (36.1%) presented a progressive motor radiculopathy with a predominance in the lumbar group (28; 43.1%) compared to the cervical group (15; 27.3%). Six (5%) patients had a history of cancer, one was immunosuppressed, and one had unexplained weight loss. Sixteen (13.4%) had history of trauma. Cauda equina syndrome was suspected in one patient and in 12 (10.1%), spinal stenosis was suspected. Thirty-seven (31.1%) patients had no improvement of pain with conservative treatment, and the proportion was higher in the lumbar group (25 patients (38.5%). No patient had osteoporosis, recent infection, fever of unknown cause, spondyloarthropathy, intravenous drug use, or prolonged use of steroids. Seventy-three MRIs (63%) were ordered by family physicians with a higher proportion in cervical spine MRI (42 (76.4%)). The subgroup of MRI ordered in the first 90 days of onset had similar medical history and red flags.

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics of MRI requestsFootnote *

* No case of osteoporosis, recent infection, fever of unknown cause, spondyloarthropathy, intravenous drug use, or prolonged use of steroids.

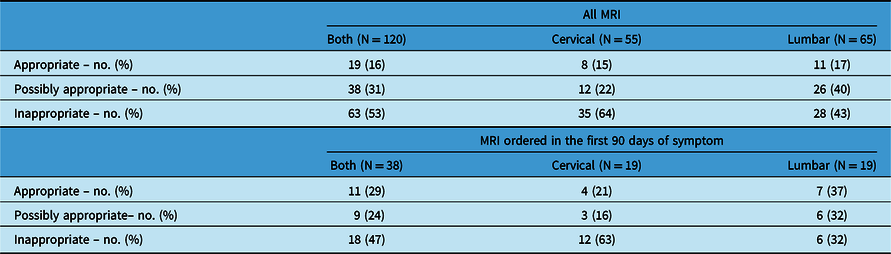

Appropriateness of MRI requests is summarized in Table 2. Inappropriate MRI requests were classified in 63 (53%) cases with a higher proportion in the cervical group (34 (64%)) than the lumbar group (28 (43%)). Appropriate and possibly appropriate requests were 19 (16%) and 38 (31%), respectively. Similar proportions of inappropriate requests were found in the subgroup with an MRI ordered in the 90 days of symptoms onset.

Table 2: Appropriateness of MRI requests

Interpretation

Our study demonstrates that despite recommendations against the use of spine MRI in low back pain or neck pain without red flags, there is an important overuse of this imaging modality in our region, with 53% of inappropriate MRI requests overall. Forty-three percent of lumbar MRIs and 64% of cervical MRIs were inappropriately ordered, and the subgroup of MRIs ordered in the first 90 days of onset has a similar proportion of inappropriate requests. Our results of inappropriateness are higher than other studies previously published. In 2016, Gidwani et al. reported retrospectively 31% of inappropriate lumbar spine MRI in the Veterans Health Administration of the USA. Reference Gidwani, Sinnott, Avoundjian, Lo, Asch and Barnett10 Kovacs et al. classified in inappropriate group 10.6% of lumbar MRI in their prospective multicentric study in Spain. Reference Kovacs, Arana and Royuela9 Both studies classified MRI with only information on the MRI requests contrary to our study in which we also analyzed information in EMG reports, which are much more detailed. Those studies based respectively their criteria of appropriateness on CMS criteria endorsed by the National Quality Forum, USA and on the indication criteria established by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence, the American College of Physicians and Radiology. The criteria for inappropriate use of MRI were therefore different between each study. To our knowledge, no study has been published about the appropriateness of cervical spine MRIs.

Our study is the first to demonstrate over-ordering based not only on information from MRI requests but also on information from EMG consultations. The EMG consultation reviews allowed us to obtain more detailed medical history like the presence or absence of a motor radiculopathy and date of initial symptoms, information that is not always included on MRI requests. It can partially explain the difference with other studies previously published. However, our population based on EMG consultations could have overestimated the proportion of radiculopathy compared to the general population of low back pain or neck pain. One of the important issues emphasized by INESSS, in their interactive tool, and could explain a part of the inappropriate use is that sensory radiculopathy pain without progressive motor deficits in an acute situation is not an appropriate indication of spine MRI. 8

This study would not have been possible based only on information on MRI requests because those requests lacked major data essential to stratify their appropriateness with the INESSS criteria, like the time from onset, the presence of motor radiculopathy, and other red flags. This lack of requirements for pertinent details should probably be corrected in the future to allow optimal use of resources in a publicly funded health care system. Also, with excluding MRI requests without EMG reports, our study is underestimating the quantity of spine MRI orders in general population, and thus the fraction of inappropriate MRI is probably much larger indeed.

Bias of information is intrinsic to retrospective studies. We minimized it by reviewing EMG reports in addition to MRI requests. Omission of clinical details in both could still have biased the classification of some cases in our study. With the large time frame between initial symptom and MRI ordering, recall bias could have influenced our results. However, we obtained a comparable proportion of appropriateness in the subgroup that had MRIs ordered within 90 days of initial symptoms.

This study suggests that over-ordering of spine MRIs for low back pain or neck pain is an important problem in our region, likely contributing to the long delays to access this imaging modality. Interactive tools like the one from INESSS and the Choosing Wisely Campaign are part of the solution but need to be systemically applied by physicians. We suggest instead to develop regional or provincial standardized requests with the indication of spine MRI, and these would need to be reviewed with sanctions for requests not corresponding to the criteria. We think that it will reduce inadequate ordering more efficiently and improve access to MRIs for all patients.

Disclosures

HMM reports no disclosures. FE reports no disclosures. CB reports an investment in Imeka.

Statement of Authorship

HMM: conceptualized and created the research protocol, reviewed the literature, collected and analyzed the data, and drafted and reviewed the manuscript. FE: supervised the project and helped in reviewing and conceptualizing the protocol of research and the manuscript. CB: Helped in reviewing and conceptualizing the protocol of research and the manuscript.