Cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) refers to thrombosis of the draining dural venous sinuses and deep and superficial cerebral veins. It is a rare cause of stroke, affecting approximately 1/100,000 annually.Reference Ferro, Correia, Pontes, Baptista and Pita 1 , Reference Borhani Haghighi, Edgell and Cruz-Flores 2 Anticoagulation is the mainstay of treatment, although evidence for its efficacy has never been confirmed in large randomized trials, and optimal choice of anticoagulant at initial presentation and for maintenance therapy is unknown.Reference Saposnik, Barinagarrementeria and Brown 3 , Reference Einhaupl, Stam and Bousser 4 Knowledge of current national patterns of practice with regards to management of CVT is unknown. We surveyed Canadian neurologists and hematologists regarding their use of anticoagulation for treatment of CVT.

METHODS

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia. Participants were recruited from two national email lists: the Canadian Stroke Consortium (CSC), which has 125 physician members involved in treatment of stroke, mostly neurologists, and Thrombosis Canada (TC), which has 70 physician members, mostly hematologists, involved in treatment of thrombosis. The survey consisted of 15 questions regarding individual patterns of practice for initial and maintenance anticoagulation for CVT, estimated annual case volume at the respondent’s center, and demographic information. Minor specialty-specific modifications were made for the CSC and TC surveys, and the survey was available to respondents in either English or French (see Supplementary data). Responses were anonymized. Participation in a draw to win a $50 Amazon gift card was offered as an incentive. The survey remained open for 3 months, and one reminder was sent to each list after 6 weeks.

Individual participant responses were exported from the survey’s web interface (FluidSurveys University platform) into SPSS 23 (Armonk, NY) and analyzed using descriptive statistics, chi-square, and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests as applicable.

RESULTS

Twenty-nine of 113 (25.6%) physicians on the mailing list for the CSC and 22/70 (31.4%) physicians from the TC list participated. Unless respondents on the CSC and TC lists identified themselves as nonneurologists or nonhematologists (n = 4), we assumed that these respondents were specialists in those areas (neurologists, n = 27; hematologists, n = 20). The majority of respondents devoted more than 50% of their practice to stroke neurology (81.5% of neurologists) or thrombosis (60.0% of hematologists) (Supplementary Table 1).

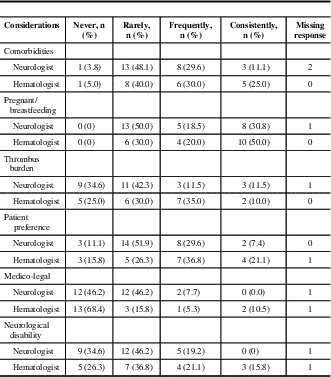

For initial anticoagulation in CVT, neurologists preferred unfractionated heparin as a first-line agent (89%), compared with 50% of hematologists (p = 0.002). Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) was also first-line for 50% of hematologists (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1). For maintenance anticoagulation, warfarin was the first choice for neurologists and hematologists (85.2% and 70.0%, respectively). The majority (57.1%) of neurologists reported that they would prescribe LMWH as a second choice for maintenance anticoagulation; 25% would use a direct oral anticoagulant. For hematologists, 53% chose LMWH and 16% direct oral anticoagulant as second-line anticoagulant (Figure 2). Factors cited as most frequently or consistently contributing to choice of anticoagulant in the acute and maintenance phase for both specialties were comorbidities, whether the patient was pregnant or breastfeeding, and, for the maintenance phase, patient preference (Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 1 First- and second-choice anticoagulants for initial treatment of CVT by speciality.

Figure 2 First- and second-choice anticoagulants for maintenance treatment of CVT by speciality.

Table 1 Factors affecting choice of initial anticoagulant

Table 2 Factors affecting choice of maintenance anticoagulant

The majority of neurologists routinely chose a duration of anticoagulation of less than 1 year (6 months or less, 44.4%; >6 months but <1 year, 25.9%); a minority made their decisions based on repeat vascular imaging (14.8%) or hematology consultation (14.8%). The majority of hematologists also chose a treatment period of less than 1 year (≤6 months, 50%; >6 months but <1 year, 30%). A minority of hematologists chose to treat for longer than 1 year (20%), and none chose repeat vascular imaging to determine duration of treatment (Table 3).

Table 3 Duration of anticoagulation by specialty

DISCUSSION

In this cohort, there are differences between neurologists and hematologists with regards to initial choice of anticoagulant in CVT. As many as 30% to 40% of patients with CVT present with venous hemorrhage on presentation,Reference Girot, Ferro and Canhao 5 , Reference Wasay, Bakshi and Bobustuc 6 and it is possible that more complex presenting cases of CVT with concurrent venous infarction, hemorrhage, or seizure may present to neurologists as compared with hematologists. Thus, an initial preference for unfractionated heparin may reflect a desire for a reversible agent with a short half-life in the event of bleeding complications in an unstable patient, though clinically relevant bleeding remains a rare complication in patients with CVT and venous hemorrhage.Reference Ferro, Correia, Pontes, Baptista and Pita 1 , Reference Bousser, Chiras, Bories and Castaigne 7 - Reference Wingerchuk, Wijdicks and Fulgham 9 However, most neurologists and hematologists endorsed that thrombus burden and presence of venous haemorrhage “never” or “rarely” affected their choice of anticoagulant. Specialty-specific thought leaders as well as local patterns of practice may also influence choice of anticoagulant, although we did not have sufficient representation from a number of physicians from the same centres to examine this latter possibility.

Fewer than half of neurologists provided a second choice for maintenance anticoagulation. Whether this reflects a strong preference for warfarin alone, a lack of experience with alternative anticoagulants in a rare condition, or neurology involvement primarily in the acute treatment phase only, is uncertain.

Most neurologists and hematologists treated patients with anticoagulation for less than a year, which is consistent with contemporary management guidelines.Reference Saposnik, Barinagarrementeria and Brown 3 , Reference Einhaupl, Stam and Bousser 4 Potential rationales for prolonged treatment, such as results of thrombophilia testing, were not included in our survey. A minority (14.8%) of neurologists used repeat vascular imaging, presumably assessing for recanalization, to guide their decision-making with regards to duration of anticoagulation.

Our results should be extrapolated with caution. Limitations to this study include inherent selection biases in those who voluntarily participated in the survey, as well the means through which the survey was distributed and potential biases in the survey’s construction. The website for the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada lists 971 neurologists (adult and pediatric) and 550 hematologists practicing in Canada. Our survey respondents thus represent a small proportion of these specialists; therefore, reported practice patterns may not apply to Canadian CVT patients in general. The overwhelming majority of respondents (all but two) were from academic centres and responses may not reflect patterns of practice in the community. Our 28% response rate is consistent with other contemporary web-based physician surveys not using unconditional incentives.Reference VanGeest, Johnson and Welch 10 Given that surveys were released to both email lists simultaneously, we assume that there was no double-counting from respondents who could have subscribed to both email lists and replied to the survey twice, though, given that responses were anonymized, we do not know this for certain.

CONCLUSION

Reported patterns of practice with regards to choice of anticoagulant for CVT are heterogeneous and differ significantly in the acute phase between neurologists and hematologists. This reflects clinical equipoise regarding optimal antithrombotic strategy for CVT.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND FUNDING

The authors are grateful to Karen Earl at the Canadian Stroke Consortium and Nicola Banks and Megan Connolly at Thrombosis Canada for their assistance in distributing the survey; Drs. Ken Butcher, Michael Hill, Eric Smith, and Michel Shamy for their advice on the survey’s content and distribution; Mr. Franco Cermeno for technical assistance; and Dr. Madeleine Sharp for translating an earlier iteration of the survey, and to all participants for their assistance. TSF is supported by a Mentored Clinician Scientist Award from the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute.

Disclosures

TSF has the following disclosures: Boehringer Ingleheim Canada: research and research grant; Bayer Canada: speaker bureau, honoraria; and Bayer Canada: advisory board, honoraria. AYYL has the following disclosures: Bayer Canada: consultant, honoraria, and consulting fees; Leo Pharma: consultant, honoraria, and consulting fees; Pfizer: consultant, honoraria, and consulting fees; BMS: research support, research grant. MCC has the following disclosures: BMS, consultant/advisor, consulting fees; BMS: speaker, honoraria; Bayer: consultant/advisor, consulting fees; Bayer: speaker, honoraria; Pfizer: consultant/advisor, consulting fees; Pfizer: speaker, honoraria; Boehringer: speaker, honoraria. SA-S and GL do not have anything to disclose.

Statement of Authorship

TSF drafted the survey and the manuscript. MCC codrafted the survey and provided the French translation. SA-S and GL participated in data analysis and interpretation. AYYL revised the survey and the content of the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2016.297