1. Introduction

Since Postal (Reference Postal, Reibel and Schane1969) argued that English pronouns are essentially definite articles, pronouns cross-linguistically have often been analyzed as (or assumed to be) determiners.Footnote 1 With the adoption of the DP hypothesis (Abney Reference Abney1987), this came to mean that pronouns were treated as intransitive determiners, lacking an NP complement. For instance, Ritter (Reference Ritter1995) argues that first and second person pronouns in Hebrew are D heads. Our conception of pronouns has been further refined by Déchaine and Wiltschko (Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002: 410), who argue that the size of pronouns varies cross-linguistically (and even language-internally), with pronouns being instantiated as pro-DPs, pro-ϕ Ps, and pro-NPs, as shown in the structures in (1).

Déchaine and Wiltschko's evidence for different-sized pronouns includes the syntactic distribution of pronouns in a given language (e.g., whether they appear in argument or predicate positions), their binding possibilities (as ϕPs are argued to be able to act as bound variables, while DPs are instead argued to act as R-expressions), and their morphological properties, such as their ability to combine with determiners (see Moskal Reference Moskal2015 and Smith et al. Reference Smith, Moskal, Xu, Kang and Bobaljik2019 for other decompositional approaches to pronouns).

InuktutFootnote 2 pronouns not only corroborate this type of decompositional approach to the structure of pronouns, they appear to extend it; realizing both the exponents of an extended functional projection and a (nominal) root which is often considered to be null or elided in languages with pro-DP and pro-ϕP pronouns (Ritter Reference Ritter1995; Déchaine and Wiltschko Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002; Elbourne Reference Elbourne2001, Reference Elbourne2005; Merchant Reference Merchant2014). In particular, I argue that since pronouns conform to the word-initial root requirement of words of the language, they can undergo noun incorporation as expected of nominals (containing a root), and they exhibit categorial flexibility insofar as wh-pronouns can also serve as predicates, which is consistent with pronouns (of all types) containing overt roots.

In addition, pronouns in Inuktut appear to constitute a counter-example to the generalization made by Ghomeshi and Massam (Reference Ghomeshi and Massam2020) that pronominal number is dependent on person.Footnote 3 Instead, number-marking on Inuktut pronouns largely patterns as on common nouns. I suggest in what follows that this is tied to the fact that Inuit pronouns contain roots and are thus noun-like.

Finally, I consider arguments by Yuan (Reference Yuan2018, Reference Yuan2021) based on Adnominal Pronoun Constructions (APCs) that Inuktut pronouns are instead D heads, and provide alternative analyses of these forms that suggest they are not in fact APCs. The main empirical and theoretical claims of the present article are as follows:

In the next section, I begin by presenting some background on Inuktut pronouns. Then I present arguments that these pronouns instantiate multiple syntactic projections and include a root, drawing on evidence regarding Inuit word structure, the ability of pronouns to undergo noun incorporation, and additional aspects of the behaviour of demonstrative and wh-pronouns.

2. Background on Inuktut pronouns

Inuktut has distinct (strong) personal pronouns only for first and second persons, as illustrated in Table 1, with data from Inuinnaqtun (Western Canadian Inuktut) (Lowe Reference Leu1985a: 94–96); various demonstratives (such as una ‘this one’) are used for third person referents.Footnote 4 As with nouns in the language, three numbers are distinguished: singular, dual, and plural.Footnote 5 Pronouns also inflect for case, as discussed in section 3.1.Footnote 6

Table 1: Inuinnaqtun (absolutive) personal pronouns and sample demonstratives

While Inuktut is often characterized as a pro-drop language, it is primarily ergative and absolutive personal pronouns that are omitted, arguably because these same arguments have their phi-features coindexed on the verb (see Yuan Reference Yuan2018, and references cited therein). Personal pronouns routinely surface in oblique cases, as in (3a); in constructions without a verb, as in (3b); and for focus, as in (3c).Footnote 7

Applying the diagnostics of Déchaine and Wiltschko (Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002) to Inuktut personal pronouns, they appear to behave as pro-DPs. In particular, they have the distribution of arguments and can only act as predicates when accompanied by a copula, which in turn hosts tense, clause-type marking, and agreement.Footnote 8

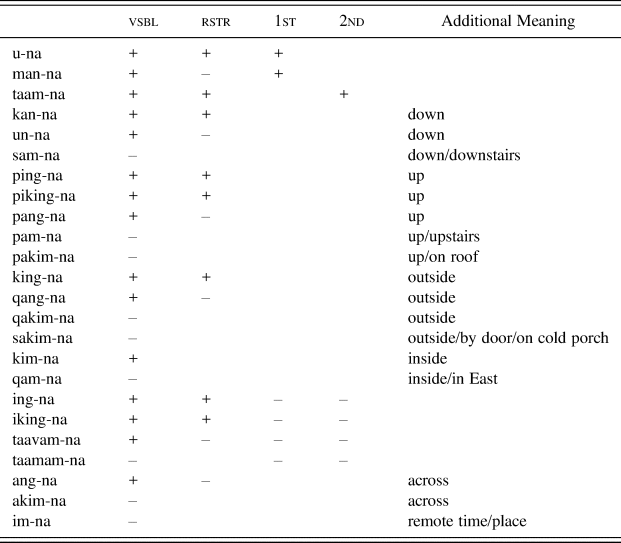

As noted above, demonstratives can be used for third persons. The language has a rich system of demonstrative pronouns, whose inventory varies by dialect. Western dialects have a particularly extensive set of contrasts, as exemplified with data from Sallirmiutun (formerly called Siglitun) in Table 2. While absolutive singular is null on nouns, it is marked by -na on demonstratives, appearing across all (and only) absolutive singular forms (as has also been reconstructed for Proto-Inuit-Yupik forms by Fortescue et al. Reference Fortescue, Jacobson and Kaplan2010: 499–526), as well as some wh-items.Footnote 9

Table 2: Sallirmiutun demonstrative pronouns (with abs.sg ending -na) (extracted from Lowe Reference Lowe1985b)

The primary contrast throughout the demonstrative system involves whether the referent is visible (abbreviated as vsbl). This is followed by a distinction between referents that are more physically restricted (rstr) in their scope and can be pointed to, as opposed to referents whose shape is more extended or whose boundaries are ill-defined (Lowe Reference Lowe1985b: 272).Footnote 10 Next, some demonstratives are specified for proximity to the speaker (first person), the listener (second person), or distance from both of these (marked by –), whereas others are underspecified with regards to distance from speech act participants. Finally, some demonstratives specify a relative spatial position above, below, inside, outside, or across. Such meanings are at times idiosyncratic, indicating objects located “upstairs”, “on the roof”, or “by the door; that one in the cold porch”, etc. (Lowe Reference Lowe1985b: 276–278). Additional forms (not shown) mark dual and plural number and the seven remaining morphological cases beyond absolutive.

While demonstratives can be used pronominally, as in (4a), they can also co-occur with a nominal restrictor, as in (4b). Although this might lead us to conclude that they are demonstrative determiners, two factors suggest otherwise. First, they can act as possessors—a property of nouns in the language—bearing a different case from the possessed noun, as shown in (5a). Second, the can be discontinuous from the nouns they modify, as illustrated in (5b), where the demonstrative is separated from a noun by the interjection haa ‘look at’.

Following Compton and Pittman (Reference Compton and Pittman2010) and Compton (Reference Compton2012), I assume demonstratives with a nominal restrictor bearing the same case to be two DPs in apposition.

Finally, the language has a set of wh-pronouns, such as suna ‘what’, kina ‘who’, and qanuq ‘how’, which also inflect for case and number and whose behaviour we return to in section 3.2.

3. Evidence for internal structure

This section presents evidence that Inuktut pronouns do not merely instantiate a single functional head, but instead instantiate multiple syntactic projections, including an overt root. While the focus is on personal pronouns, additional arguments are drawn from the behaviour of demonstrative pronouns and wh-pronouns.

3.1. Inuktut pronouns are multi-morphemic DPs

A first observation about Inuktut personal pronouns is that they contain two main parts: an initial stem indicating person (argued to be a root in the next subsection), followed by a series of functional morphemes marking person (a second time), number, and case. These two domains can be observed in Tables 3 and 4, where the various forms of the first and second person pronouns in Inuinnaqtun are presented.Footnote 11 Note that while ergative and absolutive forms are syncretic here, the two cases are distinguished elsewhere in the language (e.g., on singular unpossessed nouns, on possessed nouns, on demonstratives, and on wh-words).

Table 3: Inuinnaqtun first-person pronouns (adapted from Lowe Reference Leu1985a: 94)

Table 4: Inuinnaqtun second-person pronouns (adapted from Lowe Reference Leu1985a: 94)

The only morpheme common to all first-person forms is the stem uva. Similarly, only the stem il(i) appears in all second-person forms. Furthermore, in some dual oblique-case forms, these morphemes are the only element distinguishing first and second person. As such, we can conclude they contribute first person and second person, respectively, or analogous combinations of ϕ-features such as speaker/hearer and participant (Harley and Ritter Reference Harley, Ritter, Simon and Wiese2002). That a root might encode person is not entirely surprising, given that Déchaine and Wiltschko (Reference Déchaine and Wiltschko2002) argue that Japanese kare ‘he’ is a pro-NP consisting of a noun.

The remaining morphemes co-vary with person, number, and case (with some instances of syncretism between dual and plural) and, in fact, appear in other contexts. The absolutive and ergative endings occur as agreement on verbs, as illustrated in (6) (Lowe Reference Leu1985a: 108).Footnote 12 In particular, k and t are default realizations of dual and plural number in the language, appearing on verbs in the third person, as in (7), but also on bare unpossessed absolutive nouns (e.g., arnaq~arna-k~arna-t ‘woman, two women, more than two women’) (Kudlak amd Compton Reference Kudlak and Compton2018: xxiii).Footnote 13

The oblique form endings of pronouns also occur in other contexts, matching almost exactly the endings on the corresponding possessed nouns.Footnote 14 For instance, the first-person endings mark a first-person possessor on nouns, as in Table 5.

Table 5: Inuinnaqtun first-person possessed oblique noun (extracted from Lowe Reference Leu1985a: 71)

On some singular oblique possessed noun forms (as well as the corresponding pronouns), a velar consonant -ng- marks second person, as contrasted with a labial consonant -m/p- marking first-person forms, as shown in (8).Footnote 15 However, in other forms, this contrast is neutralized to the labial consonant, yielding forms ambiguous between first and second person, as in (9). For concreteness, I assume this syncretism to be due to feature impoverishment (Bonet Reference Bonet1991, Halle Reference Halle, Bruening, Kang and McGinnis1997), removing the feature hearer and leaving the feature participant.Footnote 16

This decompositional approach yields to the following descriptive schema for Inuit personal pronouns. An initial stem marking person, followed by an independent morpheme marking person (as further evidenced by possessive forms), a morpheme marking non-singular number, and a morpheme marking oblique cases.

(10) Template for Inuktut personal pronouns

$\sqrt \pi -\pi -(\# )-({\rm D/K})$

$\sqrt \pi -\pi -(\# )-({\rm D/K})$

Abstracting away from cases where feature impoverishment removes certain features, and setting aside pronoun roots for the moment, I propose the following structures (adapted from Ghomeshi and Massam Reference Ghomeshi and Massam2020) and Vocabulary Insertion rules for both personal pronouns and their corresponding possessor marking on nouns.Footnote 17 For convenience, I use both speaker and hearer features here in lieu of bivalent features (see, e.g., Nevins Reference Nevins2011, for arguments in favour of binary person features).Footnote 18

(12) Morphemes competing for insertion at π:Footnote 19

a. [speaker] ↔ -nga

b. [hearer] ↔ -vit

c. [speaker] ↔ -gu- / — [group]

d. [participant] ↔ -m/p- / — [oblique]

e. [hearer, participant] ↔ -ng- / — [oblique]Footnote 20

(13) Morphemes competing for insertion at #:Footnote 21

a. [group] ↔ -t

b. [group, minimal] ↔ -k

c. [group] ↔ -ti({ng/k})- / — [oblique]

d. [group] ↔ -hi(ng)- / — [oblique, hearer]

Crucially, personal pronouns are multimorphemic and structurally more complex than might be expected of simple determiners.

In the next subsection I argue that the stems of these pronouns are roots.

3.2. Inuktut pronoun stems are roots

A number of disparate phenomena point to Inuktut pronoun stems being roots as opposed to purely functional projections.

Beginning with the most general evidence, it has been observed in both descriptive and theoretical work on the language that words in Inuktut follow the schema in (14), having a root at their left edge (e.g., Johns Reference Johns, Lieber and Štekaur2014, Yuan Reference Yuan2018 and references cited therein):Footnote 22

(14) root-derivation-inflection=clitics

For instance, nominals and verbal complexes in Inuktut must normally begin with a root (Johns Reference Johns2007). This includes instances of noun incorporation, where a closed class of suffixal verbs obligatory incorporate a noun, as in (15) where the NI verb -tu- ‘consume’ must incorporate its internal argument. Similarly, a closed class of suffixal restructuring and modal verbs can also incorporate a verb (Woodbury and Sadock Reference Woodbury and Sadock1986, Johns Reference Johns, Bar-el, Déchaine and Reinholtz1999, Pittman Reference Pittman, Mahieu and Tersis2009), as in (16) where the restructuring verb -rqu- ‘order’ combines with the verb oqalo- ‘speak’.

Given the fact that modals, restructuring verbs, and incorporating verbs in the language are argued to be functional in nature (Johns Reference Johns2007, Cook and Johns Reference Cook, Johns, Mahieu and Tersis2009), this means that these elements cannot be pronounced in isolation, as they lack a root. Instead, a dummy root pi ‘do, get, thing’ is inserted in such contexts; for instance, appearing in dictionary entries to render such forms pronounceable:

That pronouns need no such dummy root to satisfy the requirements for wordhood in the language is explained if they are not solely comprised of functional material, but instead already begin with a root.

Another phenomenon involving roots (and larger projections containing them) is incorporation. Closed classes of verbs obligatorily incorporate either nominal or verbal complements—both built up from a root (see, e.g., Johns Reference Johns2007, Pittman Reference Pittman, Mahieu and Tersis2009, and references cited therein). For instance, the copula in Inuktut must incorporate its nominal complement. However, this requirement can be satisfied with a pronoun, as in (18) (from Baffin Inuktitut). Similarly, the incorporating verb -liq- ‘become’ can combine with the (case-marked) pronoun ivvititut ‘like you’, as shown in (19), which in turn is modified by -tuinnaq- ‘merely, just’.Footnote 23

The ability of pronouns to undergo incorporation also extends to demonstrative pronouns, as in the following example.

Thus, like common nouns in the language, pronouns can also undergo incorporation into verbs that obligatorily incorporate a nominal complement, further suggesting that they too contain roots. Pronouns may also undergo modification by suffixal elements that typically modify nouns, such as -ruluk ‘bad’ in the following example:

Yet another root-like behaviour among pronouns in the language is found with wh-pronouns. In addition to their use as nominal wh-expressions, many of these stems can also serve as main predicates in a clause, taking the tense, clause-type, and agreement morphology normally found with verbal roots, as illustrated in (22) and (23).Footnote 24

In sum, the ability of wh-expressions to appear as both nominal and verbal is consistent with their being acategorial roots whose category is determined by their syntactic environment.Footnote 25 As such, they too display root-like behaviour, suggesting a more general property of Inuktut is that pronouns – of all types – contain roots.Footnote 26

A final observation about wh-expressions in Inuktut is that we might expect a D-linked wh-expression like naliak ‘which’ to be a determiner, given that D-linked wh-items are presuppositional and such information is often encoded by determiners (Pesetsky Reference Pesetsky, Reuland and ter Meulen1987).Footnote 27 Crucially, unlike other wh-words which simply inflect for case and number, this wh-item also bears possessive morphology, as noted by Lowe (Reference Leu1985a,Reference Loweb,Reference Lowec):

That naliak ‘which’ bears the possessive marking normally found on nouns with third-person possessors is consistent with it too being nominal, and not of category D. Moreover, while naliak can combine with a nominal restrictor, it once again appears to be in a possessor relationship with the nominal, with the two bearing distinct morphological cases, as illustrated in (25).Footnote 28

Such examples suggest the existence of two DPs, which is again consistent with naliak containing a nominal root.

3.3. Pronominal number patterns like grammatical number on nouns

Part of deciphering the structure of Inuktut pronouns involves isolating the position of number. In a study of the morphosyntactic position of number in pronominals based on data from Persian and Niuean, Ghomeshi and Massam (Reference Ghomeshi and Massam2020: 604) make the following claims (amongst others regarding, e.g., proper nouns):

(26)

a. Grammatical number in common noun phrases is part of the nominal spine […], similarly to TP within CP, allowing for individuation, hence for referentiality.

b. Pronouns do not include a number position in their spine […]. Number in pronouns never plays a role in individuation; rather, person does.

c. Pronominal number is always bundled with π (or it is attached to another position within the pronoun) and it is always subordinate to π, which is spinal.

Ghomeshi and Massam argue that number is both syntactically and semantically distinct in pronouns and nouns, proposing that pronominal number is expected to be bundled with person. For instance, they argue that (bundled) pronominal number may be used for social deixis in Persian (see also the tu–vous distinction found in French), with a higher (grammatical) number projection being added at times to disambiguate “ambiguities created through the honorific system” (Ghomeshi and Massam Reference Ghomeshi and Massam2020: 601).

Interestingly, Inuktut seems to be an exception to generalizations (26b) and (26c), insofar as at least the first-person pronoun exhibits an identical pattern of number marking as is found on unpossessed common nouns, demonstrative pronouns, and wh-pronouns, as in Table 6 (showing absolutive forms) – all of which arguably lack (marked) person features (Ghomeshi and Massam Reference Ghomeshi and Massam2020: 601).Footnote 29

Table 6: Systematic number marking across (pro)nonominals (Inuinnaqtun; Lowe Reference Leu1985a)

As with common nouns in Inuktut, grammatical number occupies a position in the functional spine of the DP between the root and lower exponents of person, on one hand, and higher case-marking (on D or K), on the other. Even in more complex forms that are affected by allomorphy, such as the oblique pronouns in Tables 3 and 4, the set of distinct exponents (i.e., for person and number) and their relative order, as in (27) repeated from (10), suggest that person and number occupy distinct syntactic positions, with number realized on a higher projection, as might naturally be expected given the Mirror Principle (Baker Reference Baker1985).

(27) Template for Inuktut personal pronouns

$\sqrt \pi -\pi -(\# )-({\rm D/K})$

$\sqrt \pi -\pi -(\# )-({\rm D/K})$

This relative order also coincides with the fact that the exponence of number is conditioned both by person morphology and by case, as expected if it occupies an intermediate position between the two. For instance, the forms ti({ng/k})/hi({ng/k}) are the exponents of group number after -p- (marking participant), but show further conditioning according to case (see, e.g., the plural forms of the second-person pronoun in Table 4).

I propose here that the exceptionality of Inuktut pronouns with respect to the generalizations proposed by Ghomeshi and Massam (Reference Ghomeshi and Massam2020) is due to the fact that they exhibit a structure more similar to common nouns: they contain a root and the sequence of functional projections typically found with nouns, including an independent # projection.

4. Counter-evidence from adnominal pronoun constructions

As part of a much larger analysis of (split) ergativity and ϕ-marking in Inuktut, Yuan (Reference Yuan2018: 152) proposes that “independent pronouns in Inuit are bare D0s, not phrasal DPs” (see also Yuan Reference Yuan2021). Evidence for this claim is drawn from Adnominal Pronoun Constructions (APCs), following work by Postal (Reference Postal, Reibel and Schane1969) that argues that (plural) pronouns in English may combine with nouns and in such constructions are in complementary distribution with articles. Yuan (Reference Yuan2018) illustrates this phenomenon with the examples from German and Italian in (28), likening them to the Kalaallisut (West Greenlandic Inuit) example in (29a), for which she proposes the structure in (29b).Footnote 30

In addition, Yuan (Reference Yuan2018) proposes that the following examples from Inuktitut also constitute APCs, analyzing the suffixes as pronominal clitics (and observing parallel forms of agreement on verbs).

Beginning with the Kalaallisut example in (29a), there are several factors that call into question whether this is indeed an APC involving a bare D0 combining with an NP. Firstly, the word kalaalliit in (29a) includes the suffix -(i)t, marking plural number and case (albeit ambiguous between absolutive and ergative), and thus would surface identically as a full DP without the pronoun. Crucially, full DPs can occur in apposition with each other, as noted by Fortescue (Reference Fortescue1984) and illustrated in (31).Footnote 31

Given the extensive use of DP-DP appositives in the language, the proposed APC in (29a) might well involve two full DPs in apposition.Footnote 32

Turning to the Inuktitut examples in (30), as Yuan (Reference Yuan2018) observes, these same suffixes appear as ϕ-marking on verbs. Setting aside their status as clitics or agreement (although see Compton Reference Compton2014, Yuan Reference Yuan, Weber and Chen2015, Compton Reference Compton, Hammerly and Prickett2017, Johns and Kučerová Reference Johns, Kučerová, Coon, Massam and Travis2017, and Yuan Reference Yuan2018, Reference Yuan2021 for discussion), we can first note that they are formally distinct from the independent pronouns that are the focus of this article (although they appear to instantiate a subpart of these pronouns). However, in addition to this, there is reason to believe that they too are not APCs. Crucially, the ending -tigut in (30a) is in fact the expected vialis case first-person plural possessive form (cognate with the Inuinnaqtun form -ptigun in Table 5, but also identified as -(t)tigut for Inuktitut by Dorais Reference Dorais1988: 36, who calls it translative case).Footnote 33 Moreover, while the expected form of ‘teacher’ is iliniaq-ti, with an agentive nominalizing suffix, the form in (30b) appears to instead involve the intransitive declarative/participial ending -tu(q). As such, I propose the alternative glosses and translations in (32), where (32a) is a possessive construction where the vialis case adds the meaning ‘among’,Footnote 34 and (32b) is either a declarative clause or a nominalized version thereof – both of which are compatible with the participial clause-type marker.Footnote 35

To summarize, while the nature of appositive constructions in Kalaallisut, Inuktitut, and other varieties of the language, as well as properties of case and agreement, merit further study, the evidence examined here does not appear to support an analysis of these constructions as APCs (notwithstanding Yuan Reference Yuan2018, Reference Yuan2021).Footnote 36 As such, the data presented above should not lead us to conclude that Inuktut independent pronouns are D0 heads.

As pointed out by a reviewer, Yuan's (Reference Yuan2018) D0 analysis of object-indexing morphemes (i.e., what the author casts as object agreement) might still be maintained, so long as it need not apply to independent determiners, which have been argued herein to be phrasal.

5. Conclusion

While so-called function words are often assumed to be morphosyntactically atomic or contain only functional morphemes, it has been argued above that Inuktut pronouns are multi-morphemic and phrasal, containing a root (expressing person in pronominals) and an extended functional projection. This finding is similar to findings by Leu (Reference Leu2015) that demonstratives in Germanic languages should be analyzed as phrasal.

As to why pronouns should contain roots encoding person, one factor may simply be their diachronic origin. Fortescue et al. (Reference Fortescue, Jacobson and Kaplan2010: 418), in their proto-dictionary of Inuit-Yupik, suggest the first-person uva- “is apparently from the dem[onstrative] root uv-”, meaning ‘here’ (cf. uvani ‘here’; ubva/uvva! ‘right here’ and related forms in Spalding and Kusugaq Reference Spalding and Kusugaq1998). Furthermore, they suggest a link between the proto-form *əlpət ‘you’ (p.116) (cf. modern ilvit~igvit~ivvit) and the verb *ət- ‘be’ (p.128), cognate with the modern enclitic verb =it- ‘be located’, arguably a verbal root.

As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, an interesting consequence of this analysis is that “Inuktut pronouns involve neither (i) a covert nominal predicate” (Evans Reference Evans1977, Cooper Reference Cooper, Heny and Schnelle1979, Merchant Reference Merchant2014) “nor (ii) an elided or deleted nominal predicate” (Elbourne Reference Elbourne2001, Reference Elbourne2005; Merchant Reference Merchant2014), as has been assumed in much previous work on pronouns, particularly to account for cases of donkey anaphora. Instead, it is proposed herein that such roots are overt in Inuktut.

It was further argued that number in pronominals patterns with nouns in the language, insofar as it appears to be both independent and structurally higher than person marking and undergoes allomorphy conditioned by case independently from person. This exceptionality with respect to cross-linguistic generalizations proposed by Ghomeshi and Massam (Reference Ghomeshi and Massam2020) was explained by the fact that the structure of Inuktut pronouns is closer to that of nouns. The analysis herein also converges with work by Moskal (Reference Moskal2015) and Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Moskal, Xu, Kang and Bobaljik2019), that places number higher than person in pronouns.

Finally, potential counter-evidence from constructions argued by Yuan (Reference Yuan2018, Reference Yuan2021) to be APCs involving bare D0 pronouns was considered and alternative analyses for these forms were suggested, thereby maintaining the claim that Inuktut (independent) pronouns are phrasal DPs.