1. Introduction

Different languages incorporate ideophonic elements in different ways.Footnote 1 This article argues that ideophones retain some of their prototypical features even when ideophones are well integrated into a linguistic system. The data come from Japanese, which is known as a language with a huge ideophonic inventory (Kakehi et al. Reference Kakehi, Tamori and Schourup1996, Hamano Reference Hamano1998). Japanese ideophones show a high degree of morphosyntactic integration compared to some other languages, particularly in their colloquial and childish uses. However, close investigations based on quantitative and qualitative methods show that ideophonic features and grammatical constraints are retained in integrated Japanese ideophones.

This article pursues the issue of linguistic integration of ideophones from two case studies in Japanese. One study focuses on sentence-type restrictions on ideophones, which have been reported in some languages but are absent in Japanese, at least in an explicit manner. The other case study takes a further step into the sentence structure, looking at the syntactic and semantic types of verbs that Japanese ideophones are allowed to form in normal and playful/childish discourse. These cases will lead us to the general typological implication that grammatical restrictions that yield clear contrasts in the well-formedness of sentences in one language or one register of a language may be found as preferences in another.Footnote 2 The empirical identification of grammatical phenomena of this type requires a large amount of linguistic data, which are often lacking in ideophone research.

The organization of this article is as follows. In section 2, I outline the major characteristics of Japanese ideophones, with special attention to their morphosyntax. This overview allows me to formulate the hypotheses to be examined in this article. In section 3, corpus data are presented to identify weak sentence-type restrictions on Japanese ideophones. In section 4, corpus- and questionnaire-based approaches are taken to examine the violability of the previously identified syntactic and semantic restrictions on ideophonic verbs in Japanese. In section 5, I conclude by reviewing the present findings from the general perspective of ideophone typology. It is argued that greater linguistic integration of ideophones weakens these grammatical constraints.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, I outline the main characteristics of Japanese ideophones, paying special attention to their morphosyntax.

2.1 Japanese ideophones

The Japanese lexicon has at least a thousand conventional ideophonic items, more commonly known as “mimetics” in Japanese linguistics (Kakehi et al. Reference Kakehi, Tamori and Schourup1996, Hamano Reference Hamano1998). They have a set of typical formal and functional features, such as monomoraic (e.g., pon ‘popping’) and bimoraic roots (e.g., poton ‘dropping’) (Hamano Reference Hamano1998), reduplicative (e.g., potopoto ‘dropping repeatedly’) and suffixal morphology (e.g., poton ‘dropping’) (Tamori and Schourup Reference Tamori and Schourup1999, Akita Reference Akita2009: Ch. 5), prosodic prominence (Kita Reference Kita1997), dynamic semantics (Usuki and Akita Reference Usuki, Akita, Hiraga, Herlofsky, Shinohara and Akita2015), and informality (Tamori and Schourup Reference Tamori and Schourup1999). Japanese ideophones cover both auditory (e.g., piyopiyo ‘tweeting’, dosadosa ‘thudding’) and non-auditory eventualities, with the latter ranging from manner of motion (e.g., sutasuta ‘walking briskly’) to shine (e.g., kirakira ‘twinkling’), texture (e.g., sarasara ‘dry and smooth’), pain (e.g., zukizuki ‘one's head throbbing’), and psychological experience (e.g., wakuwaku ‘excited’).

What is of particular relevance to the present article is the morphosyntax of Japanese ideophones. They have maximally five syntactic-categorial possibilities: acategorial, quotative-adverbial, bare-adverbial, verbal, and nominal-adjectival (or simply, nominal) (Kita Reference Kita1997; Kageyama Reference Kageyama, Frellesvig, Shibatani and Smith2007; Toratani Reference Toratani, Nolan and Diedrichsen2013, Reference Toratani, Hiraga, Herlofsky, Shinohara and Akita2015; Akita and Usuki Reference Akita and Usuki2016; Usuki and Akita Reference Usuki, Akita, Hiraga, Herlofsky, Shinohara and Akita2015). Each of these categorial realizations is illustrated in (1).

-

(1)

-

a. ? Nurunuru, unagi-wa subet-te it-ta.(acategorial)

idph eel-top slip-conj go-pst

‘Slip-slip, the eel went slipping.’

-

b. Unagi-wa nurunuru-to subet-te it-ta. (quotative-adverbial)

eel-top idph-quot slip-conj go-pst

‘The eel went slipping slipperily.’

-

c. Unagi-wa nurunuru subet-te it-ta.(bare-adverbial)

eel-top idph slip-conj go-pst

‘The eel went slipping slipperily.’

-

d. Sono unagi-wa nurunuru-si-ta.(verbal)

that eel-top idph-do-pst

‘The eel felt slippery.’

-

e. Sono unagi-wa nurunuru-dat-ta.(nominal)

that eel-top idph-cop-pst

‘The eel was slippery.’

-

As illustrated in (1a), acategorial ideophones occur at the left or right edge of a sentence, prosodically separated from the rest of the sentence (Tamori and Schourup Reference Tamori and Schourup1999: 84–88). This use is quite rare and essentially limited to onomatopoeic ideophones. Unlike the syntactically isolated ideophones prevalent in some languages (Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz Reference Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001), acategorial ideophones in Japanese are only found in highly informal or poetic discourse. Adverbial ideophones are marked with either a quotative particle or zero, as illustrated in (1b) and (1c), respectively. Bare-adverbial ideophones and their host verbs (e.g., nurunuru ‘slipping’ and sube- ‘slip’ in (1c)) together behave like loose complex predicates (Toratani Reference Toratani, Vance and Jones2006, Akita and Usuki Reference Akita and Usuki2016). Verbal and nominal uses, illustrated in (1d) and (1e), can also constitute predicative constructions. The verbal construction is primarily headed by the dummy verb su- ‘do’ (section 4), whereas the nominal construction involves a copula.

The five ideophonic constructions differ from each other in terms of the degree of morphosyntactic integration, as represented as the hierarchy in (2) (Kita Reference Kita1997, Reference Kita2001; Akita and Usuki Reference Akita and Usuki2016; Dingemanse and Akita Reference Dingemanse and Akita2016).Footnote 3

-

(2) The morphosyntactic integration of ideophones in Japanese:

acategorial < quotative-adverbial < bare-adverbial < verbal < nominal

non-integratedintegrated

Acategorial ideophones are located at the low end of the hierarchy due to their obvious prosodic independence and their occasional holophrastic realization (i.e., occurrence without non-ideophonic elements). The morphosyntactic integration of other ideophone types is measured by a set of linguistic criteria, such as omissibility and indivisibility (Toratani Reference Toratani, Hiraga, Herlofsky, Shinohara and Akita2015). Compare the following examples illustrating the two tests with the originals in (1). As (3) shows, acategorial and adverbial ideophones can be omitted without affecting the grammaticality of the sentences where they belong, whereas verbal and nominal ideophones cannot.

-

(3) Omissibility:

-

a. Nurunuru , unagi-wa subet-te it-ta.(acategorial)

idph eel-top slip-conj go-pst

‘ Slip-slip , the eel went slipping.’

-

b. Unagi-wa nurunuru-to subet-te it-ta.(quotative-adverbial)

eel-top idph-quot slip-conj go-pst

‘The eel went slipping slipperily .’

-

c. Unagi-wa nurunuru subet-te it-ta.(bare-adverbial)

eel-top idph slip-conj go-pst

‘The eel went slipping slipperily .’

-

d. * Sono unagi-wa nurunuru-si -ta.(verbal)

that eel-top idph-do-pst

‘The eel felt slippery .’

-

e. *Sono unagi-wa nurunuru-dat -ta.(nominal)

that eel-top idph-cop-pst

‘The eel was slippery .’

-

The sentences in (4) show that the ideophonic parts of verbal and nominal ideophones cannot be separated from their tensed parts (i.e., the verb su- ‘do’ and the copula -da) by intervening phrases or clauses. Bare-adverbial ideophones exhibit similar but weaker resistance to separation, suggesting that they are combined more tightly with their host predicates than quotative-adverbial ideophones (Akita and Usuki Reference Akita and Usuki2016).

-

(4) Indivisibility:

-

a. ? Nurunuru, [hure-ru-to] unagi-wa subet-te it-ta.(acategorial)

idph touch-npst-when eel-top slip-conj go-pst

‘Slip-slip, when [I] touched [it], the eel went slipping.’

-

b. Unagi-wa nurunuru-to [hure-ru-to] subet-te it-ta.(quotative-

eel-top idph-quot touch-npst-when slip-conj go-pstadverbial)

‘The eel went slipping, when [I] touched [it], slipperily.’

-

c. ?? Unagi-wa nurunuru [hure-ru-to] subet-te it-ta.(bare-adverbial)

eel-top idph touch-npst-when slip-conj go-pst

‘The eel went slipping, when [I] touched [it], slipperily.’

-

d. * Sono unagi-wa nurunuru [hure-ru-to] si-ta.(verbal)

that eel-top idph touch-npst-when do-pst

‘The eel felt, when [I] touched [it], slippery.’

-

e. * Sono unagi-wa nurunuru [hure-ru-to] dat-ta.(nominal)

that eel-top idph touch-npst-when cop-pst

‘The eel was, when [I] touched [it], slippery.’

-

Another indivisibility test using focus particles diagnoses verbal ideophones as having looser structural unity than nominal ideophones, as illustrated in (5) (see Kageyama Reference Kageyama, Frellesvig, Shibatani and Smith2007).

-

(5)

-

a. Sono unagi-wa nurunuru-wa si-ta.(verbal)

that eel-top idph-top do-pst

‘The eel indeed felt slippery.’

-

b. * Sono unagi-wa nurunuru-wa dat-ta.(nominal)

that eel-top idph-top cop-pst

‘The eel was indeed slippery.’

-

2.2 Hypotheses

In this article, I hypothesize and explore a negative correlation between the degree of morphosyntactic integration of ideophones and the strength of grammatical restrictions on them. This hypothesis is motivated by the recent empirical investigations into the inverse correlation between the morphosyntactic integration of ideophones and their ‘expressiveness’. Ideophones are typically accompanied by a set of emphatic features, such as prosodic foregrounding (Nuckolls Reference Nuckolls1996) and expressive morphology (for instance, vowel lengthening, partial reduplication; Zwicky and Pullum Reference Zwicky and Pullum1987), and the frequency of these ‘expressive’ features has been found to decrease as a function of the degree of morphosyntactic integration (Dingemanse Reference Dingemanse2011: Ch. 6; Dingemanse and Akita Reference Dingemanse and Akita2016; Akita, Reference Akitato appear; Dingemanse, to appear; see also Childs Reference Childs2014). In fact, similar (and more general) discussion has been repeatedly made under somewhat impressionistic notions, such as “ideophonicity/lexicality” (Tamori and Schourup Reference Tamori and Schourup1999; cf. Newman Reference Newman, Erhard Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001) and “iconicity” (Akita Reference Akita2009: Ch. 7). The discussion concludes that ideophones lose their ideophonic tone when they are formally integrated into the sentence structure or become part of the prosaic lexicon. These studies remain somewhat impressionistic because they fail to clearly define the key notions of an ideophonic tone and morphosyntactic integration.

I solve this general problem by focusing on two specific grammatical restrictions on typical ideophones: sentence-type restrictions and verb-type restrictions. These restrictions replace the vague dimension of an ideophonic tone. Moreover, our hierarchy of ideophonic constructions in (2) gives a specific picture to the notion of morphosyntactic integration. Thus, the specific hypotheses to be examined in this article can be stated as in (6).

-

(6)

-

a. Hypothesis 1 (to be examined crosslinguistically in section 3):

Sentence-type restrictions are weaker (or absent) in ideophones with higher morphosyntactic integration.

-

b. Hypothesis 2 (to be examined intralinguistically in section 4):

Verb-type restrictions are weaker (or absent) in ideophones with higher morphosyntactic integration.

-

I examine these hypothesized negative correlations both intra- and cross-linguistically. Both within and across languages, there are differences in how deeply ideophones are morphosyntactically integrated. First, Japanese has five major ideophonic constructions with different degrees of morphosyntactic integration (section 2.1). As I discuss in section 4, language-internal differences in the morphosyntactic integration of ideophones are also found between registers (that is, normal vs. colloquial, childish). Second, the average degree of morphosyntactic integration of Japanese ideophones appears to be higher than that of ideophones in languages like Semai (Austroasiatic; Diffloth Reference Diffloth, Lenner, Thompson and Starosta1976) and Kambera (Austronesian; Klamer Reference Klamer, Kitto and Smallwood1999), which are known to have no ideophonic predicates (Dingemanse, to appear). This idea is further corroborated by the abovementioned stylistic limitations on acategorial ideophones in Japanese.Footnote 4 Based on these facts and assumptions, I examine Hypothesis 1 (sentence-type restrictions) in a crosslinguistic context and Hypothesis 2 (verb-type restrictions) within Japanese.

3. Study 1: Sentence-type restrictions

In this section, I quantitatively examine Hypothesis 1 by looking at how ideophones are distributed across different types of sentences in a corpus of spoken Japanese, which is assumed to represent high linguistic integration of ideophones (section 2.2).

3.1 Descriptions

Sentence-type restrictions have been, sometimes partly and sometimes controversially, noted for ideophones in several languages, including Hausa (Afro-Asiatic, Newman Reference Newman1968); Kisi (Niger-Congo, Childs Reference Childs, Hinton, Nichols and Ohala1994); KiVunjo Chaga (Niger-Congo, Moshi Reference Moshi1993); Khmu (Austroasiatic, Svantesson Reference Svantesson1983); Chadic, Sundanese, and Korean (isolate, Diffloth Reference Diffloth, Peranteau, Levi and Phares1972); and Chinese (Sino-Tibetan, Aihara and Han Reference Aihara and Han1990, for certain reduplicative items with some ideophonic properties). The sentence-type restrictions restrict the occurrence of ideophones in these languages to basic types of sentences (affirmative-declarative sentences); they cannot occur in non-basic (interrogative, imperative, and negative) sentences. For example, Newman (Reference Newman1968) observes that, in Hausa, the ideophonic adverbs (termed “descriptive adverbs”) illustrated in (7) are subject to the sentence-type restrictions, whereas the quasi-ideophonic adverbs (termed “verbal intensifiers”) illustrated in (8) are not. Quasi-ideophonic items appear to have lost some of their ideophonic identity. As I describe in section 3.3, Japanese also has a set of quasi-ideophonic adverbs that are quite free from the sentence-type restrictions.

-

(7) Hausa ideophonic adverbs: (Newman Reference Newman1968: 110–111)

-

a. Ya faɗi sharap.(affirmative-declarative)

he fall idph

‘He fell headlong.’

-

b. * Ya faɗi sharap?(interrogative)

‘Did he fall headlong?’

-

c. * Tashi farat!(imperative)

get.up idph

‘Get up in a flash!’

-

d. * Bai tashi farat ba.(negative)

neg get.up idph neg

‘He didn't get up in a flash.’

-

-

(8) Hausa quasi-ideophonic adverbs:(Newman Reference Newman1968: 110–111)

-

a. Ya ƙone ƙurmus.(affirmative-declarative)

he burn completely

‘It burnt to the ground.’

-

b. Ya ƙone ƙurmus?(interrogative)

‘Did it burn to the ground?’

-

c. Cika ta pal!(imperative)

fill it full

‘Fill it full!’

-

d. Bai cika pal ba.(negative)

neg fill full neg

‘He didn't fill it up completely.’

-

On the other hand, Japanese ideophones can readily occur in both basic and non-basic sentences, as illustrated in (9).Footnote 5

-

(9)

-

a. Ai-wa nikoniko-to warat-ta.(affirmative-declarative)

Ai-top idph-quot smile-pst

‘Ai smiled brightly.’

-

b. Ai-wa nikoniko-to warat-ta-no?(interrogative)

Ai-top idph-quot smile-pst-ques

‘Did Ai smile brightly?’

-

c. Ai, nikoniko-to warai-nasai!(imperative)

Ai idph-quot smile-imp

‘Ai, smile brightly!’

-

d. Ai-wa nikoniko-to waraw-anakat-ta.(negative)

Ai-top idph-quot smile-neg-pst

‘Ai didn't smile brightly.’

-

Thus, unlike the languages cited above, Japanese does not have obvious sentence-type restrictions on ideophones. Hypothesis 1 allows us to predict that even ideophones in Japanese, presumably a language with highly integrated ideophones, may exhibit some preference for basic sentences (Prediction 1), and that the preference is greater in constructions with lower morphosyntactic integration, such as the quotative-adverbial construction (Prediction 2). Such a preference will suggest the gradual nature of ideophone typology, in which acceptability contrast in one linguistic system may be retained as frequency contrast in another.

3.2 Methods

I used 27 informal conversations between two to four (old) friends in the Nagoya University Conversation Corpus. This subpart of the corpus contains 19 conversations between female speakers, one conversation between male speakers, and seven conversations between male and female speakers. The total length of the conversations was 21.88 hours, and they contained 28,277 sentences (507,208 morphemes). This corpus is appropriate for the present research purpose because, unlike corpora of monologues and written discourse, it contains many interrogative and imperative sentences.

I obtained 582 tokens of ideophones and 339 tokens of “quasi-ideophones” (Tamori Reference Tamori1980, Tamori and Schourup Reference Tamori and Schourup1999, among others). I compared ideophones and quasi-ideophones because of their minimal difference. Quasi-ideophones are degree, frequency, or intensity adverbs with putative ideophonic origin, such as dandan ‘gradually’, dondon ‘increasingly’, kit-to ‘surely’, kitin-to ‘properly’, sot-to ‘gently’, sukkari ‘completely’, and zut-to ‘all the time’. They are recognizable by their morphological and semantic characteristics. They have prototypical ideophonic shapes, such as reduplicative and suffixal shapes, and, due to their event-general semantics, they are as frequent as non-ideophonic adverbs (Akita Reference Akita2012, Toratani Reference Toratani2012). In the present corpus, the mean type-token ratios for ideophones and quasi-ideophones were 43.30% and 10.11%, respectively. I manually coded the type (that is, affirmative-declarative, interrogative, imperative, or negative) of the sentence containing each ideophone/quasi-ideophone token. Prediction 1 leads us to expect that ideophones should exhibit a greater preference for basic sentences than quasi-ideophones.

3.3 Results

Some instances are cited in (10) and (11). Construction types are coded within the sentences.

-

(10) Ideophones:

-

a. Demo gozyuu-en-kurai [Quot-adv babababat-te] oti-tyau-node

but 50-yen-about idph-quot fall-end.up-because

[V bikkuri-si]-ta-koto-ga aru-n-desu-kedo-ne. (032, affirmative-declarative)

idph-do-pst-nml-nom be-nml-cop.pol-but-sfp

‘But as [the payphone] consumed about ¥50 very quickly, [I] was astonished.’

-

b. Un, wasyoku-da-kedo [N kotekote-zya]-naku-tte. (080, negative)

yeah Japanese.food-cop-but idph-cop.top-neg-and

‘Yeah, [I want to have] a Japanese cuisine but not an overly Japanese one.’

-

-

(11) Quasi-ideophones:

-

a. Yoosuruni, “[Bare-adv wazawaza] uke-ru-no?” -tte-i-u

in.short idph take-npst-ques -quot-say-npst

sekai-dat-ta-n-da-kedo…(047) (interrogative)

world-cop-pst-nml-cop-but

‘In short, it was like “Do you bother to take [the entrance exam]?”‘

-

b. Toriaezu, [Quot-adv zut-to] massugu it-tyat-te-kudasai. (004 imperative)

for.now idph-quot straight go-end.up-conj-pol.imp

‘For now, please go straight on.’

-

The data were found to support both of our predictions. First, ideophones appeared more frequently (92.10%) than quasi-ideophones (78.17%) in basic sentences (χ 2(1) = 36.66, p < .001), supporting Prediction 1. The detailed distribution of non-basic sentences was not very striking for either ideophones (interrogative, 26; imperative, 3; negative, 17) or quasi-ideophones (interrogative, 39; imperative, 7; negative, 31).

Second, the data sorted by construction in Table 1 give partial support to Prediction 2. The frequency of nominal ideophones in basic sentences is significantly lower than that of the other four categories (χ 2(1) = 12.50, p < .001). This result is not too surprising, since nominal ideophones are at the extreme integrated end of the scale given in (2), repeated here as (12).

-

(12) The morphosyntactic integration of ideophones in Japanese:

acategorial < quotative-adverbial < bare-adverbial < verbal < nominal

non-integratedintegrated

Table 1. Ideophonic/quasi-ideophonic constructions and sentence types

This property makes them similar to quasi-ideophones (Kita Reference Kita1997: 391), which occur more freely in non-basic sentences than do ideophones. See (10b) for a nominal ideophone and (11) for quasi-ideophones, in non-basic sentences. In fact, there was no significant difference between the results for nominal ideophones and those for quasi-ideophones (χ 2(4) = 1.28, p = .87).Footnote 6

The present results suggest that Japanese ideophones, in particular the less integrated ones, are subject to the sentence-type restrictions, but as a statistical preference. Therefore, aside from the difference between a tendency and a grammatical contrast, both in Japanese and in the languages mentioned in section 3.1, higher morphosyntactic integration is associated with a less restricted distribution. In the next section, I argue that a similar pattern holds for language-internal generalizations about ideophones, focusing on the restrictions on the types of ideophonic verbs in normal and babytalk/playful Japanese.

4. Study 2: Verb-type restrictions

In this section, I discuss the linguistic integration of Japanese ideophones from another angle: their verb-type restrictions in normal and babytalk/playful discourse. Unlike the crosslinguistic view in section 3, this section takes a close look at how the grammatical restrictions on ideophones differ between two different registers of one language. Specifically, by observing qualitatively and quantitatively how syntactic and semantic restrictions on ideophonic verbs are retained and/or violated in childish/colloquial Japanese, I examine Hypothesis 2: the verb-type restrictions are weaker (or absent) in ideophones with higher morphosyntactic integration.

4.1 Descriptions

Japanese ideophonic verbs are highly morphologically integrated, as we saw in section 2. They are formed with two productive verbalizers. One is su- ‘do’, which incorporates non-onomatopoeic ideophones to form various types of complex verbs, as shown by Kageyama's (Reference Kageyama, Frellesvig, Shibatani and Smith2007) classification cited in (13a) (see also Akita Reference Akita2009: Ch. 6, Tsujimura Reference Tsujimura, Rainer, Gardani, Luschützky and Dressler2014). The other verbalizer is iw- ‘say’, which combines with any onomatopoeic ideophone to represent the spontaneous emission of sound, as illustrated in (13b) (Toratani Reference Toratani, Hiraga, Herlofsky, Shinohara and Akita2015, Akita and Usuki Reference Akita and Usuki2016). Note that, as shown in (13), the two verbalizers are in complementary distribution. Su- ‘do’ can never be replaced by iw- ‘say’, and iw- cannot be replaced by su- without producing a playful or childish effect, marked with “#”.Footnote 7

-

(13)

-

a. Ideophonic ‘do’-verbs:(adapted from Kageyama Reference Kageyama, Frellesvig, Shibatani and Smith2007: 44)

Activity: akuseku-{su/*iw}- ‘work hard’

Translational activity: urouro-{su/*iw}- ‘wander around’

Psychological: gakkari-{su/*iw}- ‘be disappointed’

Physiological: zukizuki-{su/*iw}- ‘feel (one's head/teeth) throb’

Physical perception: guragura-{su/*iw}- ‘wobble’

Characterizing predication:assari-{su/*iw}- ‘taste light’

-

b. Ideophonic ‘say’-verbs:

kyaakyaa-{iw/??su}- ‘scream’ buubuu-{iw/*su}- ‘oink, complain’

piyopiyo-{iw/*su}- ‘tweet’ wanwan-{iw/*su}- ‘bark’

banban-{iw/#su}- ‘bang’ gatyagatya-{iw/#su}- ‘clatter’

gorogoro-{iw/*su}- ‘roar’ katakata-{iw/??su}- ‘clatter’

patapata-{iw/??su}- ‘flutter’ zyuuzyuu-{iw/*su}- ‘sizzle’

-

These morphosyntactically highly integrated uses of ideophones are subject to the following two restrictions (Akita Reference Akita2009: Ch. 6, Toratani Reference Toratani, Hiraga, Herlofsky, Shinohara and Akita2015).

-

(14)

-

a. The anti-transitivity restriction:

Ideophones cannot form highly transitive/causative verbs.

-

b. The anti-motion restriction:

Ideophones for manner of motion cannot form verbs.

-

The existence of the anti-transitivity restriction is already suggested in the lists in (13), which contain only intransitive verbs. In fact, the verbalization of ideophones for highly causative events, such as a causative change of state, results in clear unacceptability (e.g., *paripari-su- ‘crack (a pane of glass)’, *bokiboki-su- ‘crunch (a thick stick)’). These ideophones are instead realized as adverbs (e.g., paripari(-to) war- ‘break with a cracking sound’, bokiboki(-to) or- ‘break with a crunching sound’), which are lower in the integration hierarchy in (12).

The anti-motion restriction works more narrowly and is perhaps subsumed by a more general constraint (Akita Reference Akita2009: Ch. 6). Japanese has a group of ideophones depicting manner of spatial motion, which cannot be verbalized with either su- ‘do’ or iw- ‘say’. If verbalized with su-, these ideophones would have a marginal and highly childish/colloquial tone. As illustrated in (15), this is true for manner-of-motion ideophones for both animate and inanimate entities. They are always realized as adverbs (e.g., nosinosi(-to) aruk- ‘walk in a lumbering manner’, barabara(-to) kobore- ‘drop in a pattering manner’).

-

(15)

-

a. Animate:

nosinosi-{*#su/*iw}- ‘lumber’ pyokopyoko-{*#su/*iw}- ‘hop’

sorosoro-{*su/*iw}- ‘walk gingerly’ sugosugo-{*su/*iw}- ‘leave dejectedly’

suisui-{*#su/*iw}- ‘swim smoothly’ sutasuta-{*#su/*iw}- ‘walk briskly’

tekuteku-{*#su/*iw}- ‘walk lightly’ tobotobo-{*#su/*iw}- ‘plod’

tokotoko-{*#su/*iw}- ‘walk with short steps’

tukatuka-{*su/*iw}- ‘walk unreservedly’

-

b. Inanimate or animacy-neutral:

barabara-{*#su/*iw}- ‘be scattered’ daradara-{*#su/*iw}- ‘drip’

dosadosa-{*su/*iw}- ‘thud’

gorogoro-{*#su/*iw}- ‘roll (of a heavy object)’

harahara-{*#su/*iw}- ‘flutter (of a leaf)’

horohoro-{*#su/*iw}- ‘run down (of teardrops)’

korokoro-{*#su/*iw}- ‘roll (of a light object)’

poroporo-{*#su/*iw}- ‘fall (of light, small objects)’

potupotu-{*#su/*iw}- ‘begin to rain’

suton-to-{*#su/*iw}- ‘fall right on the ground’

-

Apparent counterexamples can be noted for both restrictions. First, some previous studies of ideophonic verbs include the impact/contact verbs and reflexive verbs listed in (16a) and (16b), respectively. Impact/contact verbs are transitive verbs that do not entail a change of state (Kageyama Reference Kageyama, Frellesvig, Shibatani and Smith2007: 53, Toratani Reference Toratani, Nolan and Diedrichsen2013). Reflexive verbs cooccur with body-part NPs (Tsujimura Reference Tsujimura, Fried and Boas2005: 148–149, 2014; Kageyama Reference Kageyama, Frellesvig, Shibatani and Smith2007: 47; Toratani Reference Toratani, Nolan and Diedrichsen2013: 54–57).

-

(16)

-

a. Impact/contact verbs:

#dondon-su- ‘pound’#gosigosi-su- ‘scrub’

#gyut-to-su- ‘hold tightly’#huuhuu-su- ‘blow’

#kotyokotyo-su- ‘tickle’#kutyakutya-su- ‘chew’

#peropero-su- ‘lick’#tonton-su- ‘tap’

#tuntun-su- ‘poke’

-

b. Reflexive verbs:

#(hane-o) batabata-su- ‘flap (one's wings)’

#(asi-o) burabura-su- ‘swing (one's legs)’

#(kuti-o) mogumogu-su- ‘move (one's mouth) chewing food’

#(kuti-o) pakupaku-su- ‘open and close (one's mouth) repeatedly’

#(me-o) patikuri-su- ‘blink (one's eyes) in wonderment’

#(me-o) patipati-su- ‘blink (one's eyes)’

-

Crucially, both types of transitive verbs are low in transitivity (or causativity) and have a clearly childish/playful tone (Kageyama Reference Kageyama, Frellesvig, Shibatani and Smith2007: 48–49). This stylistic property disappears when these ideophones are used adverbially (e.g., dondon(-to) tatak- ‘hit with a bang’, burabura(-to) yuras- ‘swing repeatedly’). Therefore, all these instances are compatible with the anti-transitivity restriction.

Next, one might regard the ideophonic translational activity verbs listed in (17) (originally termed “manner-of-motion verbs” by Kageyama Reference Kageyama, Frellesvig, Shibatani and Smith2007) as exceptions to the anti-motion restriction. However, as Sugahara and Hamano's (Reference Sugahara, Hamano, Hiraga, Herlofsky, Shinohara and Akita2015) corpus-based investigation suggests, these verbs appear to represent the totality of the activity involving motion, rather than particular rates of motion or movement of particular body parts, and should therefore be included in the “activity” class in (13a).

-

(17) burabura-su- ‘stroll’ ?nyoronyoro-su- ‘wriggle’

tyokomaka-su- ‘bustle around’ tyokotyoko-su- ‘run around busily’

tyorotyoro-su- ‘run around’ urotyoro-su- ‘run around’

urouro-su- ‘wander around’ yotayota-su- ‘totter’

yotiyoti-su- ‘toddle’

In summary, Japanese ideophonic verbs are incompatible with high transitivity and with manner-of-motion meaning. Also important are the clearly childish/playful tones of some ideophonic ‘do’-verbs, notably impact/contact verbs and reflexive verbs. Such examples indicate that the two restrictions do not hold for certain registers of Japanese—namely, babytalk and highly colloquial speech (Akita Reference Akita2009: Ch. 6; Tsujimura Reference Tsujimura2009, Reference Tsujimura, Rainer, Gardani, Luschützky and Dressler2014). Put differently, these special registers appear to integrate ideophones to a greater extent than does the plain register of Japanese. This contrast between registers mirrors the crosslinguistic contrast in the average morphosyntactic integration of ideophones discussed in section 2.2. In what follows, I examine Hypothesis 2: whether the two restrictions on ideophonic verbs in normal Japanese are weaker (or absent) in colloquial/childish Japanese. Study 2a is a corpus-based study that looks at how the two restrictions on ideophonic verbs are violated in actual informal discourse, and Study 2b is a questionnaire-based study that tests how violable the two restrictions are.

4.2 Study 2a

I conducted a corpus-based investigation to see what types of unconventional ideophonic verbs (that is, those violating the anti-transitivity restriction or the anti-motion restriction) are used in actual Japanese discourse. I used the Balanced Corpus of Contemporary Written Japanese (BCCWJ), which is a collection containing about 100,000,000 words from not only relatively formal types of discourse (e.g., magazines, newspapers, textbooks, and minutes of the DietFootnote 8 ) but also highly informal (e.g., online question-and-answer threads and blogs) and creative (e.g., literary works) types of discourse. Using the NINJAL-LWP for BCCWJ system (version 1.00), I searched that corpus for 577 reduplicative ideophones identified by Kakehi et al. (Reference Kakehi, Tamori and Schourup1996).

I obtained 23 types and 46 tokens of unconventional uses of ideophonic ‘do’-verbs. As the representative instances cited in (18) show, most of the unconventional ideophonic verbs are the “childish/colloquial” types described in section 4.1 (i.e., (18a–c)). “Caused-motion” examples may be included in the impact/contact type. For example, kurukuru-su- in (18d) can be understood as representing a twirling action applied to spaghetti.

-

(18)

-

a. Impact/contact (14 types, 26 tokens):

… karada-o gosigosi-su-ru-toki-ni …

body-acc idph-do-npst-when-dat

‘… when [my hamster] scrubs [its] body …’

(Yahoo! Answers, 2005, BCCWJ)

-

b. Reflexive (2 types, 11 tokens):

Tada kuti-o pakupaku-su-ru-dake-dat-ta.

just mouth-acc idph-do-npst-only-cop-pst

‘[He] only opened and closed [his] mouth repeatedly.’

(Hiroshi Ito, Abuku Akira-no awa-no tabi [Bubble Akira's bubbly journey], 2005, BCCWJ)

-

c. Sound emission (1 type, 2 tokens):

Yure-ru-tabi-ni tiisa-na mado-ga gatapisi-si-ta.

shake-npst-whenever-dat small-cop window-nom idph-do-pst

‘The small window rattled every time [it] shook.’

(Taeko Nakamura, trans., Tubasa-yo, kita-ni [North to the orient], 2002, BCCWJ)

-

d. Caused-motion (6 types, 7 tokens):

Sonnani kirei-ni kurukuru-si-naku-te i-i-ga …

so neat-cop idph-do-neg-conj good-npst-but

‘Though [you] don't need to twirl [the spaghetti] so neatly …’

(Yahoo! Answers, 2005, BCCWJ)

-

Similar results were obtained from two smaller corpora, the Aozora Bunko Corpus (a literary corpus) and the Nagoya University Conversation Corpus (see section 3.2): impact/contact, 2 tokens; reflexive, 2 tokens; sound emission, 4 tokens; caused-motion, 2 tokens. The Aozora Bunko Corpus also contained an instance of a manner-of-motion ideophonic verb, which is cited in (19).

-

(19) Sosite sore-wa, bon-no naka-de yoriwake-rare-ru

and that-top tray-gen inside-in sort-pass-npst

azuki-no-yoo-ni, korokoro-si-ta.

adzuki.bean-gen-like-cop idph-do-pst

‘And it [post horse] tumbled like an adzuki bean being sorted on a tray.’

(Yoshiki Hayama, Umi-ni ikuru hitobito [Men who live on the sea], 1926, ABC)

The present corpus data suggest that the two restrictions on Japanese ideophonic verbs are not freely violable even in informal and creative registers (see Tsujimura Reference Tsujimura2009, Reference Tsujimura2013, Reference Tsujimura, Rainer, Gardani, Luschützky and Dressler2014). Notably, the three corpora provided no single explicit instance of a causative change-of-state ideophonic verb that would clearly violate the anti-transitivity restriction. Likewise, the high exceptionality of (19) indicates the strength of the anti-motion restriction. Moreover, all unconventional sound-emission ideophonic verbs, such as gatapisi-su- ‘rattle’ in (18c), have natural-sounding ‘say’-verb counterparts (e.g., gatapisi-iw- ‘rattle’) and can safely be considered their ad hoc substitutes.

The limited size of the data set prevents us from making any conclusive argument. In particular, the present data tell us nothing about ideophonic verb forms that were not found. They might or might not be acceptable. Therefore, in the next section, I reinforce the present findings with a questionnaire-based introspective investigation.

4.3 Study 2b

For a better understanding of the violability of the two restrictions on Japanese ideophonic verbs, I conducted a follow-up study using 80 simple sentences with ideophonic verbs. The stimulus set contained 26 sentences with conventional ideophonic verbs that fall into Kageyama's (Reference Kageyama, Frellesvig, Shibatani and Smith2007) classes in (13a), and 24 instances of unconventional ideophonic verbs. Four sentences were constructed for each of the following six semantic types of unconventional ideophonic verbs on the basis of the discussion in section 4.2: impact/contact, reflexive, caused-motion, sound emission, causative change of state, and manner of motion. The remaining 30 sentences were intended to be dummy stimuli that, I assumed, involved unambiguously ungrammatical semantic structures as verbs, such as Mai-ga neko-o nyaanyaa-si-ta ‘Mai meowed the cat’ with the intended reading ‘Mai made the cat meow.’ Two questionnaires with 40 stimuli were created from these sentences.

I asked 43 undergraduate students at Osaka University who are native speakers of Japanese (6 female, 37 male) to judge the naturalness of the 40 simple sentences in one of the two questionnaires. Based on the findings in section 4.2, I provided three choices: “natural”, “babytalk”, and “unnatural”. Each questionnaire started with three practice sentences that were assumed to draw three different judgments.

In (20), the most “unnatural” sentence of each of the six types of unconventional ideophonic verbs is cited, along with the percentage of “unnatural” answers for that sentence.

-

(20)

-

a. Onnanoko-ga huton-o panpan-si-ta.(impact/contact, 8.70%)

girl-nom futon-acc idph-do-pst

‘A girl slapped the futon.’

-

b. Kodomo-ga yubi-o guruguru-si-ta.(reflexive, 29.17%)

child-nom finger-acc idph-do-pst}

‘The child whirled [his] (index) finger.’

-

c. Mai-ga tobotobo-si-te i-ta.(manner of motion, 44.44%)

Mai-nom idph-do-conj be-pst

‘Mai was plodding.’

-

d. Kodomo-ga to-o garagara-si-ta.(caused-motion, 54.55%)

child-nom door-acc idph-do-pst

‘A child rattled the sliding door (shut).’

-

e. Onnanoko-ga mado-o baribari-si-ta.(causative change of state,

girl-nom window-acc idph-do-pst95.83%)

‘A girl shattered the windows.’

-

f. Kuruma-ga buubuu-si-te i-ta.(sound emission, 57.89%)

car-nom idph-do-conj be-pst

‘A car was zooming.’

-

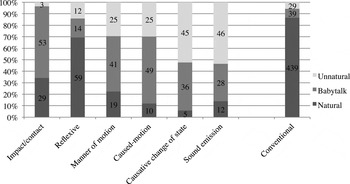

The results are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Naturalness of ideophonic verbs

In accordance with the corpus study in section 4.2, both conventional ideophonic verbs (e.g., ukiuki-su- ‘feel happy’ [psychological]) and impact/contact (e.g., tuntun-su- ‘poke’) and reflexive ideophonic verbs (e.g., (me-o) kyorokyoro-su- ‘move (one's eyes) restlessly’), which mildly violate the anti-transitivity restriction, were found to be highly acceptable. Significantly, many participants judged impact/contact verbs as “babytalk”. It was also suggested that babytalk may even allow other unconventional types of ideophonic verbs, particularly manner-of-motion (e.g., pyokopyoko-su- ‘hop’) and caused-motion verbs (e.g., kurukuru-su- ‘twirl’). However, about half of the participants judged causative change-of-state verbs (e.g., bokiboki-su- ‘crunch (a thick stick)’) and onomatopoeic verbs for spontaneous sound emission (e.g., kusukusu-su- ‘giggle’) as “unnatural”, even as child-directed words. Comparing the present perception data with the production data in section 4.2, the consistent dispreference for causative change-of-state ideophonic verbs may reflect the relative precedence of the anti-transitive restriction over the anti-motion restriction. The low acceptability of sound-emission su-verbs appears to be attributed to the participants’ awareness of their conventional iw-verb counterparts.

In summary, the present observations of the syntactic/semantic restrictions on ideophonic verbs in Japanese can be rephrased in a similar way to the crosslinguistic discussion of sentence-type restrictions on ideophones in section 3. The two restrictions on ideophonic verbs are weaker, rather than absent, in the babytalk and playful registers of Japanese, which generally integrate ideophones to a greater extent than normal Japanese. What exists as grammatical contrast in one register of a language may be found as preference in another.

5. Conclusion and typological implications

In this article, I have discussed the negative correlation between the degree of morphosyntactic integration of ideophones and the strength of grammatical restrictions on them. Study 1 argued that the sentence-type restrictions reported for ideophones in several languages also apply to Japanese ideophones, but as a force that makes ideophones prefer affirmative-declarative sentences. Study 2 found that two semantic/syntactic restrictions on ideophonic verbs in the normal register of Japanese also apply to its babytalk and playful registers, but again to a lesser extent. Assuming that Japanese, particularly its babytalk/playful register, is a language with relatively highly integrated ideophones, the two sets of results support the inverse correlation between morphosyntactic integration and grammatical restrictions.Footnote 9

One inevitable question that remains to be asked is what determines the degree of morphosyntactic integration of ideophones in each linguistic system. The century-long literature on ideophones does not provide a satisfactory answer to this question. I therefore conclude by listing three possible factors in the morphosyntactic integration or independence of ideophones. The first factor is the so-called “framing typology” (Talmy Reference Talmy2000). Japanese normally encodes a core schema (e.g., Path of motion) in the main verb (e.g., arui-te hair- [walk-conj enter] ‘enter walking’). A co-event (e.g., Manner of motion) expressed by ideophones must therefore be encoded otherwise (e.g., as an adverb, as in sutasuta-to arui-te hair- [idph-quot walk-conj enter] ‘enter walking briskly’). However, some languages (e.g., Newar, a Sino-Tibetan language) that typically encode a core schema outside the main verb also appear to make frequent use of ideophonic adverbs (Yo Matsumoto, personal communication). Furthermore, languages like French lexicalize both core schemas and ideophony in verbs (Matsumoto Reference Matsumoto and Chiba2003). The existence of these exceptions suggests that there are multiple factors in the integration of ideophones. The second possible factor is the colloquial nature of a linguistic system. As we saw with the babytalk and playful registers of Japanese, colloquial language tends to have high flexibility in grammar, and this flexibility may allow ideophones to come to belong to various categories, including highly integrated ones. The third possibility is the quantitative and/or qualitative abundance of ideophonic inventories. A large ideophonic lexicon with various semantic types may call for grammatical distinctions (see Akita Reference Akita2009: Ch. 7 for a related discussion). This last possibility (and perhaps the other two possibilities as well) may seem quite naïve, but will still be important in light of their potential connection to the unsettled question about what makes a language rich in ideophones (Childs Reference Childs1996, Kunene Reference Kunene, Erhard Voeltz and Kilian-Hatz2001, Nuckolls Reference Nuckolls2004).

The present study of Japanese ideophones contributes to the ongoing effort to develop a full typology of ideophones. Typological investigations along the lines discussed in this article can benefit from Japanese linguistics, which has both a long history of ideophone research and many well-designed corpora. As I have demonstrated in this article, these historical and technical advantages permit an effective combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches, which is not always easy in fieldwork studies.