1. Introduction

The present article provides a study of the Latin unity cardinal unus, which is the diachronic source of indefinite articles in Romance languages. I will focus mainly on its behaviour in discourse in Jerome's Vulgate (late 4th century CE). My main empirical claim will be made in section 2, where I will show that unus had not yet acquired non-cardinal uses, and that all uses of unus are attested for the unity cardinal one in contemporary English. This claim argues against the proposal that the first clear attestations of indefinite article uses appeared in the Vulgate (claimed notably by Coleman Reference Coleman and Gvozdanović1991).

In section 3, I propose a formal semantic analysis of unity cardinals, and also provide an account of how their distribution is impacted by their potential alternatives (bare nouns in Latin, the indefinite article in English), based on previous work by Grønn and Sæbø (Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012). The aim of this section is to drive home the idea that the distribution of a linguistic item does not only depend on its intrinsic meaning and properties, but also on the meanings and properties of alternatives a speaker might choose.

Based on this, I will provide in section 4 a tentative account of the first steps of grammaticalization of indefinite articles. The main claim here is that scope phenomena that have been observed in the grammaticalization literature can be explained as being motivated by Horn's division of pragmatic labor between bare singulars and NPs modified by unity cardinals, and that in earlier stages of development the marked unity cardinal is used for marked semantic (and, notably, scope) configurations.

1.1 From unity cardinals to indefinite articles

We know that unity cardinals (i.e., cardinals expressing the number 1, e.g., English one) are one of the diachronic sources of indefinite articles (see Kuteva et al. Reference Kuteva, Heine, Hong, Long, Narrog and Rhee2019: 299ff.). There is a also a great wealth of literature in formal (and other) semantics on the indefinite article, from many differing perspectives and in different frameworks (see, among many others, Heim Reference Heim1988, Hawkins Reference Hawkins1991, Kamp and Reyle Reference Kamp and Reyle1993, Reinhart Reference Reinhart1997, Brasoveanu and Farkas Reference Brasoveanu and Farkas2011, Steedman Reference Steedman2012, Grønn and Sæbø Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012). Therefore, we have a comparatively good understanding of one stage in the grammaticalization process. There is also a good amount of literature on the direction of change for a few language families (for instance, in Romance, see, e.g., Carlier Reference Carlier2001 Reference Carlier and Arteaga2013, Pozas Loyo Reference Pozas Loyo2010), and we thus have a good idea of the general direction of change. However, as far as I am aware, there has been a rather generalized lack of interest in the meaning and behaviour of the diachronic origin of these indefinite articles (but see Dahl Reference Dahl1985 for an exception to this rule). Therefore, we unfortunately know very little about the behaviour that is to be expected from a unity cardinal. Without a good understanding of the starting point, we cannot hope to grasp the overall development of indefinite articles, and may even fail to discern what is new behaviour for them at any given point in time. Furthermore, the fact that a more recent point on the developmental path is so much better understood than its origin may introduce a teleological bias in the review of the data. The main aim of this article is therefore to show that the discourse behaviour of unity cardinals is far from trivial, and that examples of type (1) do not cover the whole picture of the use of a standard unity cardinal.

(1) John drank one bottle of beer.

The received standard-model of the grammaticalization of indefinite articles is provided by Heine (Reference Heine1997: 72ff.), based on earlier work by Givón (Reference Givón1981). It proposes a five-stage framework of the process, which is depicted in (2).

(2)

The different initial stages (1–4) are mainly distinguished by their discourse (and scopal) behaviour, whereas in later stages (4–5) the disappearance of selectional restrictions regarding the modified noun also come into play. English ‘one’ (as seen in (1)) is a typical representative of the numeral in stage 1. Heine (Reference Heine1997: 72) characterizes the ‘presentative marker’ stage 2 as follows:

This stage is reached when the article introduces a new participant presumed to be unknown to the hearer and this participant is taken up as definite in subsequent discourse […]

Stage 2 uses would correspond to determiners which appear to introduce important characters at the beginning of a story, as in (3), but do not appear systematically with secondary characters, or in contexts of the specific use of a noun phrase.

(3) Once upon a time, there was a king …

Heine (Reference Heine1997: 72) insists on the importance of subsequent mentions following the use of the element introduced by one. Furthermore, presentatives have obligatorily wide scope, and narrow scope behaviour does not resurface until much later (in stage 4).

A stage 3 indefinite article is only employed to introduce specific uses of a noun (see (4a)), but does not appear in non-specific uses (see (4b)).

(4) Yesterday, I met an opera singer …

a. …namely Rolando Villazón.

b. …but I have no idea who that was.

English a(n) is a stage 4 indefinite article, since it can be used in both specific and non-specific contexts, but is restricted to singular count nouns, and cannot combine with plural count nouns or singular mass nouns, as is illustrated in (5). A full stage 5 indefinite article would be acceptable in all three of these contexts.

(5)

a. I saw a singer.

b. *I saw a singers.

c. *I saw a money.

As far as I am aware, researchers in the grammaticalization tradition generally seem to have taken the cardinal stage to be unproblematic;Footnote 1 Heine (Reference Heine1997: 72), for instance, devotes only five lines to stage 1 of the process. As I will try to show in this article, since both discourse and scopal behaviour of these forms is extremely important, we have to thoroughly investigate the behaviour of unity cardinals in these contexts.

One of the puzzles this received grammaticalization theory poses in the context of the development of scopal behaviour is that it assumes that aspects of the scope behaviour of the cardinal simply disappear in stages 2–3, and reappear at stage 4. This contrasts with hypotheses like the one in Pozas Loyo (Reference Pozas Loyo2010), which assumes that there is not much meaning change involved between a unity cardinal and indefinite articles, and that changes primarily concern frequency of use. More generally, in Heine's received grammaticalization-theory plot of the evolution of indefinite articles, there is no explicit link between known meaning components of the cardinal, and stages in the model. Consider (6):

(6) Every donkey ate one carrot.

In the most probable reading of (6), one carrot takes narrow scope with respect to every donkey, so taking wide scope is not intrinsically linked to the semantics of the unity cardinal. In Russian, an unaccented cardinal has precisely this restriction on wide-scope readings (see Heine Reference Heine1997: 72), while accentuated cardinals can appear with narrow scope.Footnote 2 Of interest here is that it is uneconomical to assume that narrow-scope readings systematically disappear and reappear in the grammaticalization process of indefinite articles, and the different choices that speakers make with regards to the scope of unity cardinals needs to be explained.

Here I establish a more solid baseline for what can be expected from a unity cardinal by investigating the discourse behaviour of English one, and seeing how it can be used to explain the discourse behaviour of Latin unus. The general idea is that – since unus is a less economical form than a bare nominal in Latin (or the indefinite article in English) – its presence must somehow be motivated. To this end, I will integrate a formal characterization of unity cardinals into the framework of Grønn and Sæbø (Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012). Based on this investigation, I will then take a glance at the developmental stages in the rise of indefinite articles, and how they can be explained.

I have chosen the Vulgate Footnote 3 (a translation of the Bible by St. Jerome, ≈347–420 CE, commissioned by Pope Damasus in 382), because it contains certain uses of unus N Footnote 4 that have been claimed to be ‘innovative’, in the sense that they look suspiciously like modern indefinite articles, see, for example, Matthew (26:69), classified by Coleman (Reference Coleman and Gvozdanović1991: 390) as one of the ‘unequivocal examples of articular meaning’ (that is: with the meaning of an indefinite article):

Una ancilla in (7) introduces a new discourse participant, and is generally translated by the indefinite article in English versions of the Bible, rather than a unity cardinal (which would sound odd here). As we will see below in (13), however, (7) can be explained (away) as a standard cardinal use of unus.

However, before being able to tackle the issue in Latin, we will need to investigate uses of the unity cardinal one in English, in order to get a better understanding of how these expressions are used in discourse. While the English article system is clearly different from that of late Latin, this will provide us with a baseline against which ‘grammatically advanced’ uses of unity cardinals can be evaluated.

1.2 Unity cardinals in discourse: a preliminary look at English one

The present section is not meant to provide an exhaustive description of the discursive uses of one in English. Its purpose is merely to describe the basic pattern in order to better understand the facts in the Vulgate. I have chosen English one as a blueprint for establishing the discourse-semantic meaning of unus because in English, the unity cardinal one is morphologically clearly distinct from the indefinite article a (contrary to, e.g., Romance languages, or written standard German). Furthermore, one would expect one to be unaffected by any ongoing process of grammaticalization, since the presence of the indefinite article a should block it. I will come back to a more precise characterization of the constraints on the use of one in section 3.

According to standard dynamic semantics (e.g., Kamp and Reyle Reference Kamp and Reyle1993), indefinite articles introduce new discourse participants. This is also the case for many uses of one in English. A first use, which I will refer to as the partitive use, introduces a new referent into the discourse, which is part of a larger entity previously introduced into the discourse. Consider (8).

The entity denoted by one cow in (8) is in a sense discourse new. Yet, it also is a part of a plural discourse referent already introduced (a lot of cows).

With an indefinite article, a partitive reading is difficult to get:

(9) We saw a lot of cowsI. #[A cow]i∈I appeared to be looking at me with an attitude.

One is also often used in contrastive contexts, either when there is a contrast to another token of the same kind (see (10a)), or when there is a contrast between two cardinals (see (10b), which I will refer to as numeral contrast):

-

(10)

a. One cow was looking at me; another (cow) simply ignored me.

b. Peter drank one bottle of beer; Fred had three (bottles).

In both contexts, the indefinite article would be slightly strange.Footnote 5 Notice, however, that the indefinite article does not generally exclude partitive interpretations; they are only not very salient in most contexts.

(11) That wasn't A reason I left Pittsburgh, that was THE reason.Footnote 6

However, as shown by (9), the indefinite article cannot refer back as a partitive anaphora to a close and explicitly given plural antecedent.

The Latin determiner system is not identical to the one in contemporary English (English has fully grammaticalized indefinite and definite articles, whereas Latin has bare noun (phrases) and a rather limited use of ille – which is the ancestor of most Romance definite articles). However, as we will see, this preliminary investigation gives us a useful blueprint for what uses we should be looking at in Latin.

Generally, the point is that the more an occurrence of unus looks inexplicable in terms of a unity cardinal, the more we will be tempted to classify it as an indefinite article. Therefore, knowing what to expect is crucial.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: based on our summary description of English one, we will look in more detail at uses of unus in the Vulgate that seem to be problematic. Then, we will go back to English in order to better characterize the meaning of unity cardinals in terms of their antipresuppositions (see Percus Reference Percus and Ueyama2006, Sauerland Reference Sauerland and Steube2008, Grønn and Sæbø Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012, Amsili and Beyssade Reference Amsili and Beyssade2016), and apply these ideas to Latin. A section describing the changes required for a unity cardinal to become an indefinite article concludes the article.

2. A detailed look at ‘innovative’ uses of adnominal UNUS in the Vulgate

In this section I will take a detailed look at instances of adnominal uses of unus which appear at first sight to be indefinite articles, that is, where there are no motivations for the presence of a unity cardinal in the immediate vicinity.Footnote 7 Each time, I will try to identify elements that may have motivated the use of unus. Since the earliest stages of grammaticalization of the indefinite article are assumed to involve major characters in a story,Footnote 8 I will also comment on the respective importance of the character.

Most uses of unus in the Vulgate are entirely unproblematic, given an analysis as a cardinal: they are either used in contrastive contexts (see (12a)), or in partitive contexts like (12b–c).Footnote 9

In what follows, I will look at uses of unus that are both adnominal and which I have classified as introducing a new discourse participant, and therefore, might be instances of an indefinite article.Footnote 10 Often, in looking at the larger context, the motivation of the use of unus will become clear.

2.1 Clear cases of cardinal use with unusual distance

To begin, let us have a second look at (7) – which was supposed to be a clear instance of an article use – in a slightly larger context (Matthew (26:69–71).

(13) 69 Petrus vero sedebat foris in atrio et accessit ad eum una ancilla dicens et tu cum Iesu Galilaeo eras 70 at ille negavit coram omnibus dicens nescio quid dicis 71 exeunte autem illo ianuam vidit eum alia et ait his qui erant ibi et hic erat cum Iesu Nazareno

69 But Peter sat without in the court. And there came to him a servant maid, saying: Thou also wast with Jesus the Galilean. 70 But he denied before them all, saying: I know not what thou sayest. 71 And as he went out of the gate, another maid saw him; and she saith to them that were there: This man also was with Jesus of Nazareth.

It turns out that (13) – instead of being a clear instance of a (proto-) indefinite article – is clearly an instance of a contrastive use: una ancilla as opposed to alia. However, the distance between these two elements is abnormal (viewed from the perspective of contemporary English):Footnote 11 there are two instances of direct speech between the occurrences of unus and its contrasting alius, as well as their introductory formulæ. Furthermore, una ancilla in (14) is quite close to a throw-away referent:Footnote 12 it refers to an extremely secondary character, and is not taken up again. Notice that such occurrences of unus are not what one would expect from a stage 2 presentative, which should mark important, and salient characters at the beginning of a tale (see Heine Reference Heine1997: 72).

The same pattern (‘standard’ use, non-standard distance) also obtains in Judges (9:53) (here in the enlarged context of Judges (9:51–54)).

(14) 51 erat autem turris excelsa in media civitate ad quam confugerant viri simul ac mulieres et omnes principes civitatis clausa firmissime ianua et super turris tectum stantes per propugnacula 52 accedensque Abimelech iuxta turrem pugnabat fortiter et adpropinquans ostio ignem subponere nitebatur 53 et ecce una mulier fragmen molae desuper iaciens inlisit capiti Abimelech et confregit cerebrum eius 54 qui vocavit cito armigerum suum et ait ad eum evagina gladium tuum et percute me ne forte dicatur quod a femina interfectus sim qui iussa perficiens interfecit eum

51 And there was in the midst of the city a high tower, to which both the men and the women were fled together, and all the princes of the city, and having shut and strongly barred the gate, they stood upon the battlements of the tower to defend themselves. 52 And Abimelech, coming near the tower, fought stoutly: and, approaching to the gate, endeavoured to set fire to it: 53 And behold, a certain woman casting a piece of a millstone from above, dashed it against the head of Abimelech, and broke his skull. 54 And he called hastily to his armourbearer, and said to him: Draw thy sword, and kill me: lest it should be said that I was slain by a woman. He did as he was commanded, and slew him.

In verse 53, we have a discourse-new woman, reinforced with ecce. However, this refers back as a partitive to the plural discourse referent mulieres, in verse 51. Therefore, this is an instance of the partitive case. And once again, we have a throw-away referent: this particular referent is not taken up again.Footnote 13

2.2 Slightly less clear cases

The next type of use resembles at first glance the examples we have seen before, although upon closer scrutiny, they may not be identical.

A partitive instance of such a case can be illustrated by the following sequence from Mark (12:38–44), which is the last parable in a lengthy sequence of parables. The main point here is to caution against the scribes who “eat” the widows out of house and home – and very conveniently, in Mark (12:42), a widow comes by, thereby driving home Jesus's point.

(15) 38 et dicebat eis in doctrina sua cavete a scribis qui volunt in stolis ambulare et salutari in foro 39 et in primis cathedris sedere in synagogis et primos discubitus in cenis 40 qui devorant domos viduarum sub obtentu prolixae orationis hii accipient prolixius iudicium 41 et sedens Iesus contra gazofilacium aspiciebat quomodo turba iactaret aes in gazofilacium et multi divites iactabant multa 42 cum venisset autem una vidua pauper misit duo minuta quod est quadrans 43 et convocans discipulos suos ait illis amen dico vobis quoniam vidua haec pauper plus omnibus misit qui miserunt in gazofilacium 44 omnes enim ex eo quod abundabat illis miserunt haec vero de penuria sua omnia quae habuit misit totum victum suum

38 And he said to them in his doctrine: Beware of the scribes, who love to walk in long robes and to be saluted in the marketplace, 39 And to sit in the first chairs in the synagogues and to have the highest places at suppers: 40 Who devour the houses of widows under the pretence of long prayer. These shall receive greater judgment. 41 And Jesus sitting over against the treasury, beheld how the people cast money into the treasury. And many that were rich cast in much. 42 And there came a certain poor widow: and she cast in two mites, which make a farthing. 43 And calling his disciples together, he saith to them: Amen I say to you, this poor widow hath cast in more than all they who have cast into the treasury. 44 For all they did cast in of their abundance; but she of her want cast in all she had, even her whole living.

At first glance, this seems to be exactly the same as in (14): una vidua pauper has a plural antecedent, namely viduarum. However, while one cannot exclude that the occurrence of viduarum in verse 40 is to be taken referentially, it does not seem to be necessary to me (it might be a metaphor). If it is not taken referentially, the case for a partitive use is undermined.

The referent introduced by una vidua is developed a little bit; but once again, this is not an individual who as such has any importance in the gospel. The widow is used to make a point against the religious establishment of the times. The sequence where the widow appears is outside the warning against the scribes; yet she illustrates the point so well that it has to be taken to be a part of that sequence, and is therefore detached from the main story line.

Besides such (quasi?-)partitives, there are also cases that look like contrastive uses, but which are slightly different from what we have seen so far. In prototypical cases of contrast, we have a repetition of the predicate, or an anaphora to the same predicate. This, however, is not always the case. Let us consider Matthew (8:19–22). The wider context is the following: Jesus has been laboring through a long day of miracle-working and being solicited by all kinds of people. But now, it is evening…

(16) 19 et accedens unus scriba ait illi magister sequar te quocumque ieris 20 et dicit ei Iesus vulpes foveas habent et volucres caeli tabernacula Filius autem hominis non habet ubi caput reclinet 21 alius autem de discipulis eius ait illi Domine permitte me primum ire et sepelire patrem meum 22 Iesus autem ait illi sequere me et dimitte mortuos sepelire mortuos suos

19 And a certain scribe came and said to him: Master, I will follow thee whithersoever thou shalt go. 20 And Jesus saith to him: The foxes have holes, and the birds of the air nests; but the Son of man hath not where to lay his head. 21 And another of his disciples said to him: Lord, suffer me first to go and bury my father. 22 But Jesus said to him: Follow me, and let the dead bury their dead.

In the preceding or subsequent context, there is no mention of another scribe or scribes. Therefore, a partitive use or a contrast with respect to another scribe can be ruled out here. However, there is a contrast with alius, even though they do not share the same predicate (scribe vs. disciple). So, this particular instance of unus appears unexpected.

However, by declaring his will to follow Jesus, the scribe becomes a disciple of Jesus. The whole sequence would be perfectly as expected if it were analyzed as a pronominal unus with scriba as apposition – some guy, a scribe – which, given the near-total lack of punctuation, cannot be ruled out.

Once again, the scribe is a secondary character, and certainly no protagonist of the gospel, ruling out an analysis as a stage 2 presentative marker.

Summing up, we have discussed here cases that do not correspond perfectly to what we have come to expect from English one: i) the distance between the motivating contrast or partitive element may be greater than what is usual today in English, even though the motivating element itself is in principle clear; ii) the motivating element may not be completely obvious in the text, or may depend partially on contextual assumptions. However, given some leeway, I have tried to show that these uses are not that far removed, or can be interpreted in a way that maximizes their conformity with “standard” cardinals.

However, there are cases for which such a strategy seems to have its limits, which we will turn to now.

2.3 Cases without textual antecedent or contrastive element

While many cases seem unproblematic based on the assumed discursive effects of unus, some other uses are more difficult to reconcile with the effects we hitherto discussed – notably those that appear at the very beginning of a discourse. Such uses are interesting because they correspond to the prototypical stage 2 uses of Heine (Reference Heine1997).Footnote 14

One such case is from ISamuel (1:1–3).

(17) 1 fuit vir unus de Ramathaimsophim de monte Ephraim et nomen eius Helcana filius Hieroam filii Heliu filii Thau filii Suph Ephratheus 2 et habuit duas uxores nomen uni Anna et nomen secundae Fenenna fueruntque Fenennae filii Annae autem non erant liberi 3 et ascendebat vir ille de civitate sua statutis diebus ut adoraret et sacrificaret Domino exercituum in Silo erant autem ibi duo filii Heli Ofni et Finees sacerdotes Domini

1 There was a man of Ramathaimsophim, of Mount Ephraim, and his name was Elcana, the son of Jeroham, the son of Eliu, the son of Thohu, the son of Suph, an Ephraimite: 2 And he had two wives, the name of one was Anna, and the name of the other Phenenna. Phenenna had children: but Anna had no children. 3 And this man went up out of his city upon the appointed days, to adore and to offer sacrifice to the Lord of hosts in Silo. And the two sons of Heli, Ophni and Phinees, were there priests of the Lord.

There are no other men mentioned in the text in proximity proximity to vir unus (one man), apart from Ophni and Phinees, but these are classified as filii Heli – sons of Heli. There are, however, a few other numbered elements: two wives; two sons of Heli, which might legitimate an interpretation as a numeral contrast. Elcana is an important character in this story, because he is the father of Samuel. But what may have triggered the use of UNUS here? We are fortunate enough to have a near minimal pair in Job (1:1–3).

(18) 1 vir erat in terra Hus nomine Iob et erat vir ille simplex et rectus ac timens Deum et recedens a malo 2 natique sunt ei septem filii et tres filiae 3 et fuit possessio eius septem milia ovium et tria milia camelorum quingenta quoque iuga boum et quingentae asinae ac familia multa nimis eratque vir ille magnus inter omnes Orientales

1 There was a man in the land of Hus, whose name was Job, and that man was simple and upright, and fearing God, and avoiding evil. 2 And there were born to him seven sons and three daughters. 3 And his possession was seven thousand sheep, and three thousand camels, and five hundred yoke of oxen, and five hundred she asses, and a family exceedingly great: and this man was great among all the people of the east.

The only relevant difference concerning the entities introduced at the very beginning of the text is that Job is the main character of the book, whereas Elcana is secondary – even though the book starts with him: he is the protagonist's father. Other than that, there does not seem to be much difference here: it seems extremely unlikely that Job and Elcana were the only men in Hus and Ramathaimsophim, respectively; and in both cases, there are many numerical expressions in the immediate vicinity, which might license a reading of numeral contrast (although not with the same predicate). What one can probably deduce from this contrast is that unus was possible in such circumstances, without being obligatory.

Some might be tempted to dismiss these two cases, since they come from the Old Testament, and therefore could be argued to reflect a use of the Hebrew unity cardinal exad (‘one’), or its absence.

However, apart from the idea defended in this article that one should read the Vulgate as a coherent text, there are also empirical reasons why such cases cannot be dismissed. Indeed, there are occurrences in the New Testament where unus appears without a clear antecedent, and therefore, highlight the same problem. Consider Matthew (9:18) (with some context). Here, Jesus returns to his hometown, performing miracles. This attracts considerable attention by all sorts of people, and among the categories introduced into discourse before these verses figure scribes, tax collectors, sinners and Pharisees.

(19) 14 tunc accesserunt ad eum discipuli Iohannis dicentes quare nos et Pharisaei ieiunamus frequenter discipuli autem tui non ieiunant 15 et ait illis Iesus numquid possunt filii sponsi lugere quamdiu cum illis est sponsus venient autem dies cum auferetur ab eis sponsus et tunc ieiunabunt 16 nemo autem inmittit commissuram panni rudis in vestimentum vetus tollit enim plenitudinem eius a vestimento et peior scissura fit 17 neque mittunt vinum novum in utres veteres alioquin rumpuntur utres et vinum effunditur et utres pereunt sed vinum novum in utres novos mittunt et ambo conservantur 18 haec illo loquente ad eos ecce princeps unus accessit et adorabat eum dicens filia mea modo defuncta est sed veni inpone manum super eam et vivet

14 Then came to him the disciples of John, saying: Why do we and the Pharisees, fast often, but thy disciples do not fast? 15 And Jesus said to them: Can the children of the bridegroom mourn, as long as the bridegroom is with them? But the days will come, when the bridegroom shall be taken away from them, and then they shall fast. 16 And nobody putteth a piece of raw cloth unto an old garment. For it taketh away the fulness thereof from the garment, and there is made a greater rent. 17 Neither do they put new wine into old bottles. Otherwise the bottles break, and the wine runneth out, and the bottles perish. But new wine they put into new bottles: and both are preserved. 18 As he was speaking these things unto them, behold a certain ruler came up, and adored him, saying: Lord, my daughter is even now dead; but come, lay thy hand upon her, and she shall live.

There is nothing in the verses following this passage that could motivate the presence of unus. Therefore, much hinges on the interpretation of princeps: the New International Version and other translations render this as leader of a synagogue — which should then be a Pharisee, since the Pharisees are the religious movement historically related to synagogues. In this case, it would be a straightforward partitive use. Be that as it may, this is once again a secondary character, and therefore, not one whose textual importance would be expected to be underlined by (what might be) a stage 2 indefinite article.

The most problematic example for a simple adaptation of the discourse behaviour of English one seems to be the following instance from Matthew (21:19) (once again from the New Testament), where unus lacks an antecedent, as well as a contrast element:

(20) 18 mane autem revertens in civitatem esuriit 19 et videns fici arborem unam secus viam venit ad eam et nihil invenit in ea nisi folia tantum et ait illi numquam ex te fructus nascatur in sempiternum et arefacta est continuo ficulnea

And in the morning, returning into the city, he [Jesus] was hungry. 19 And seeing a certain fig tree by the way side, he came to it and found nothing on it but leaves only. And he saith to it: May no fruit grow on thee henceforward for ever. And immediately the fig tree withered away.

It is not immediately obvious what motivates the occurrence of unus here. A partitive is implausible, since the context strongly suggests that this tree was the only fruit tree in the vicinity. There is no contrastive element, either. As far as I have seen, most English translations seem to favor an interpretation along the lines of arbitrariness or lack of importance. However, a paraphrase along “(only) a single” might be fitting here. Such a reading is not easily expressed in contemporary English with the unity cardinal alone, but the use-case can be interpreted as a rather straightforward extension of a cardinal use.

Notice once again that the identity of the fig tree is completely unimportant; it is merely a pretext for a parable. Therefore, it cannot be taken to be an early stage 2 presentative indefinite article. The context in Matthew (21:19) is also one where an English weak some would be an appropriate translation, as far as it can convey arbitrariness and lack of importance.

Let us sum up what we have seen so far. In the Vulgate, the vast majority of the occurrences of unus are straightforward cardinal uses; some uses fit into the familiar pattern of partitive and contrastive uses, but display a distance between antecedent (or opposing) member and unus N that is much greater than what is possible today in English. In rare circumstances, the uses of unus do not pattern necessarily with what one would expect from a unity cardinal, but they can be interpreted in ways consistent with what we have seen in English. Let me stress again that none of the referents introduced by unus is a particularly important character; most of them are (close to) throw-away references. Under the assumption that the five-stage model by Heine (Reference Heine1997) is correct, and that at the beginning of the process of grammaticalization stands the use of the (proto-)indefinite article with very salient characters in narration, unus cannot have become more article-like at this stage in time.

And even if Heine's model should not be entirely appropriate, given the examples discussed and their similarity to uses of English one, there does not seem to be a compelling reason to assume that unus is anything other or anything more than a unity cardinal in the Vulgate.

3. An explicit treatment of the discursive behaviour of unity cardinals

In section 1.2 I gave a brief description of a few salient uses of one in English, namely partitive uses, and contrastive uses, and we have also seen that many uses in the Vulgate that look at first sight like indefinite articles can be viewed as variations of these uses, if considered in a larger context. The question is how these uses can be accounted for from a formal point of view.

I will argue that unity cardinals trigger antipresuppositions (also known as implicated presuppositions, see Percus Reference Percus and Ueyama2006, Sauerland Reference Sauerland and Steube2008), extending in particular the ideas of Grønn and Sæbø (Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012) and Amsili and Beyssade (Reference Amsili and Beyssade2016). I will argue that generally, projective content is a promising way of making sense of the discursive behaviour of these forms.

I will sketch the basic idea for English, and then try to carry it over to Late Latin.

3.1 Extending the game of same and different: projective content and antipresuppositions

My account of the meaning of one will extend the work on antipresuppositions by Grønn and Sæbø (Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012) on the use of indefinites, and build also on some extensions of their work done by Amsili and Beyssade (Reference Amsili and Beyssade2016). I will first present their basic ideas, and then integrate one into the framework (which I will assume to be a valid representation also for other unity cardinals, like unus).

The basic intuition of this literature concerns the “novelty condition” or effect of non-uniqueness of indefinite articles. This phenomenon is illustrated by the following example, due to Heim (Reference Heim, von Stechow and Wunderlich1991: 515f.):

(21) Richard heard the Beaux-Arts Trio last night and afterwards had a beer …

a. …with the pianist.

b. …with a pianist.

Whereas the definite article in (21a) refers to the pianist of the Beaux-Arts Trio, a pianist in (21b) suggests that the pianist was not the one of the trio. The issue with this condition is that it does not seem to hold in all contexts. Antipresupposition approaches to indefinites argue that this is not a basic, semantic feature of the meaning of indefinites, but arises from the fact that it competes in many contexts with a definite article, which contains an explicit presupposition that the entity talked about is already in the common ground (and unique, when we talk about a singular definite).Footnote 15

Grønn and Sæbø (Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012: 79) define an antipresupposition as follows:

(22) Antipresupposition

When you have a choice between two forms α and β differing only in a presupposition π, triggered by α but not by β, if the contexts supports π, you are to choose α. Thus, when you use β, this will signal the opposite: π is not supported by the context.

I will use the following representations of indefinite and definite articles based on Grønn and Sæbø (Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012) and Amsili and Beyssade (Reference Amsili and Beyssade2016)Footnote 16, using a flat DRT notation based on Sauerland (Reference Sauerland and Steube2008), where the numerator indicates the presupposition, and the denominator the assertive content:

(23) a

$\textstyle\mapsto \lambda P\lambda Q\lambda w {\textstyle\vert \over {\textstyle x\vert P_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;Q_w\lpar x \rpar }}$

$\textstyle\mapsto \lambda P\lambda Q\lambda w {\textstyle\vert \over {\textstyle x\vert P_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;Q_w\lpar x \rpar }}$(24) the

$\textstyle\mapsto \lambda P\lambda Q\lambda w{{\textstyle z\vert P_w\lpar z \rpar \comma \;{\rm card}\lpar {P_w} \rpar \,= 1} \over {\textstyle x\vert P_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;Q_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;x \,= \,z}}$

$\textstyle\mapsto \lambda P\lambda Q\lambda w{{\textstyle z\vert P_w\lpar z \rpar \comma \;{\rm card}\lpar {P_w} \rpar \,= 1} \over {\textstyle x\vert P_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;Q_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;x \,= \,z}}$

The indefinite article is assumed to contain no presupposition, whereas the definite contains the presupposition that there is already an entity satisfying the same predicate P in the context, and that the cardinality of the predicate in the context corresponds to 1. Furthermore, the definite article imposes in its assertive content an identity condition on the new discourse referent, making it identical to the already present entity, which is not the case for an indefinite.

What these representations ensure is that a and the form a Horn-scale, where the is a stronger alternative than a – which is indeed desirable, given their use in contexts like not just a N, but the N:

Therefore, the argument goes, if a is in competition with the – which is not the case in all contexts –, one will get antipresuppositions of novelty and non-uniqueness.

Grønn and Sæbø (Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012) propose that another element may impact the distribution of the indefinite article, namely another, represented as in (26).Footnote 17

(26) another

$\mapsto \lambda P\lambda Q\lambda w{{\textstyle z\vert P_w\lpar z \rpar } \over {\textstyle x\vert P_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;Q_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;x\ne z}}$

$\mapsto \lambda P\lambda Q\lambda w{{\textstyle z\vert P_w\lpar z \rpar } \over {\textstyle x\vert P_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;Q_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;x\ne z}}$

Another contains a presupposition that there is already an entity of predicate P in the context, and asserts that the new discourse referent is different from that entity. Once again, another is strictly more informative than a, and so in cases where a is in competition with another, the use of a should license the inference that the newly introduced entity is identical to the one already existing in the common ground. Grønn and Sæbø (2012: 85) argue that in cases where the speaker is assumed to have sufficient relevant knowledge, and if both the and another are competitors, the use of the indefinite article is infelicitous.

Let us now introduce one into this comparative endeavour, this game of same and different. I will assume the following representation for one:

(27) one

$\mapsto \lambda P\lambda Q\lambda w{\textstyle \vert \over {\textstyle x\vert P_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;Q_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;{\rm card}\lpar {P_w\cap Q_w} \rpar = 1}}$

$\mapsto \lambda P\lambda Q\lambda w{\textstyle \vert \over {\textstyle x\vert P_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;Q_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;{\rm card}\lpar {P_w\cap Q_w} \rpar = 1}}$

The representation in (27) thus assumes that one has no presuppositions, and that it contains a cardinality condition (![]() ${\rm card}\lpar {P_w\cap Q_w} \rpar = 1$), which is the only element distinguishing it from the indefinite article.

${\rm card}\lpar {P_w\cap Q_w} \rpar = 1$), which is the only element distinguishing it from the indefinite article.

Let us walk through this, and justify some aspects of this formalization. Notice first, that a, the, and one (as well as another) assert the existence of an entity of type P:

(28)

a. John saw the rabbit.

b. John saw a rabbit.

c. John saw one rabbit.

All of (28) entail that there exists a rabbit. And (28a) and (28c) have a uniqueness entailment: there is only one rabbit (such that they saw it). This is the familiar uniqueness-presupposition in the case of (28a), but in the case of (28c), this seems to work differently: it is compatible without any problem with the existence of several rabbits in the context (see (29a) vs. (29b)).

(29) Bugs and Bunny are both rabbits, …

a. and John saw one rabbit.

b. #and John saw the rabbit.

Since the according to (24) requires unicity only with respect to its nominal predicate (here rabbit), (29b) is predicted to fail because of the contradiction with the presupposition; (29a) is predicted to be felicitous because unicity here depends not only on being a rabbit, but also on being seen by John.

Concerning the cardinality condition, Crisma (Reference Crisma, Gianollo, Jäger and Penka2015: 146) observed that one does not behave like other cardinals, which have a “soft”, implicated upper boundary.

(30)

a. John saw two rabbits; in fact, maybe he even saw three.

b. John saw one rabbit; #in fact, maybe he even saw two.

c. John saw a rabbit; in fact, maybe he even saw two.

One explanation for the pattern in (30) could be that one necessarily has a focus on the unity cardinal, since it has an (unfocused) a clitic alternative (namely the indefinite article). However, this does not seem to be the whole story, since in embedded contexts, the focus may fall on either ’one’ or on the noun:

(31)

a. I'm sure that John saw [one]F rabbit; #in fact he maybe even saw two.

b. I'm sure that John saw one [rabbit]F; #in fact he maybe even saw two.

(31a) is infelicitous, as expected, but even (31b) does not allow for the continuation, even though the focus sensitivity operator is associated with the common noun here.Footnote 18

Notice that the definite article seems to behave more like the indefinite article than the unity cardinal, as it allows the continuation in (32). It does not seem to block reference to elements that are not (as of yet) in the common ground the way ‘one’ does.:

(32) John saw the rabbit; in fact, maybe he even saw two rabbits.

Furthermore, even though according to this formalization, one should entail a, there is probably no scale associated with the opposition between a and one, as is indicated by the infelicity of (33):

(33) ?*These girls are looking for not just a guy, but one guy.

However, the opposition is nevertheless meaningful in some contexts, and substituting one for the other can lead to strange effects.

(34)

a. John has a nose.

b. ?*John has the nose.

c. ?John has one nose.

d. ?John has one nose, and Jill has another.

As has been known at least since Hawkins (Reference Hawkins1991), in contexts like (34a), with an inalienable possession below have, definite articles are infelicitous, as is illustrated in (34b). Therefore, they are no alternatives here. However, even though humans prototypically have unique noses, one still cannot say so and use the unity cardinal when talking about inalienable possession. Even adding a contrastive element (i.e., Jill's nose, as in (34-d)) does not make things better. Intuitively, what makes (34-c) strange is that it suggests that John might have more than a single nose – which is not possible under cases of inalienable possession and standard human anatomy. This is probably best explained as follows: in using one where the indefinite would have been appropriate, the additional effort (or use of the less frequent item) must be somehow motivated (and this will thus give rise to a manner implicature). This motivation then makes scalar alternatives to one (that is, other cardinals) salient.

Indeed, even though one does not seem to be on a scale with a, it is a member of scales involving cardinals, or imprecise cardinal expressions (like several, or many):

The observation here is that, even though – according to the present formalization – one should be able to form a semantic scale with a, it is not located at the same level of grammatical saliency in English as the definite and indefinite articles: one clearly is a second-tier determiner, which has much lower frequency than the articles.Footnote 19 Therefore, there is at least a frequency effect underlying (or influencing) the range of possible choices.Footnote 20

Let us now come back to the standard cases in which one is used in English, and consider first the partitive use. In such a context, we have a plural antecedent in the common ground, and we want to assert something with respect to a single entity out of this plural antecedent. Clearly, in such a case, the definite article is infelicitous, because its presupposition fails when combined with a singular, and the assertion fails when combined with a plural. The question is, how could we account for the infelicity of the indefinite article? Competition with another should not be an issue here, since the new entity is part of the given entity. Grønn and Sæbø (Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012: 86) suggest for a slightly different case (with a singular antecedent), that the indefinite is blocked because it is a clitic: with a plural N as antecedent, the singular N has to be deaccented (since it is given), and because the indefinite article is a clitic, it cannot receive an accent, either. Hence, a is blocked, and we need something that can be accented, and has a meaning that is similar enough. One is a possible candidate, and is therefore used instead of the indefinite.Footnote 21

Second, the same type of reasoning obtains when we have the familiar opposition of one (N) with another (N). In these cases as well, if the speaker wishes to mark contrast, the noun will be deaccented, since this contrast will not involve the (identical) predicate. Therefore, this situation requires a determiner which is not a clitic (which therefore excludes the articles the and a, whose accented versions can only be used metalinguistically). If the entity is not already discourse-old, one is then the only determiner that fits the bill.Footnote 22

Numeral contrast can also be explained by the assumed semantics, since one is the only one of the considered determiners which has a cardinality specification as an asserted content (contrary to the definite determiner, which may have a cardinality specification as a presupposed, not at-issue content). The indefinite article has no intrinsic cardinal component to it, even though it will most often denotationally correspond to a cardinality of 1. Finally, there is also the effect of intonation to observe, as is illustrated in (36):

(36)

a. Marc bought one bottle, and Brett bought three bottles.

b. ?*Marc bought a bottle, and Brett bought three bottles.

c. Marc bought a bottle, and Brett bought a keg.

d. Marc bought a bottle, and Brett bought three kegs.

When the contrast is on the predicate as in (36c–d), the indefinite article is felicitous, even if the numbers are different. However, if the predicate is the same and the quantity different, the unity cardinal is obligatory, and the indefinite article infelicitous. This must be due to the contrastive stress on the determiners, which cannot be carried by a clitic like a.

So, should this kind of reasoning be correct – which is a conservative extension of the work of Grønn and Sæbø (Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012) and Amsili and Beyssade (Reference Amsili and Beyssade2016) –, the reason one is used in a number of contexts instead of the indefinite article is mainly because it can be accented, while still being sufficiently close in meaning to the article. Indeed, in many contexts, an indefinite article will also imply that there is no plural entity, which is why the additional meaning of one is not a handicap.

3.2 UNUS in Latin: Alternatives and effects

Let us now go back to the Vulgate. We have seen in section 2 that the patterns seen with unus are close, though not completely identical, to what we observe in English. Assuming, furthermore, that the linguistic phenomenon distinguishing the use of the unity cardinal and the indefinite determiner has been correctly identified as antipresupposition, it is important to know what the alternatives to unus were in the Latin of the Vulgate. The major difference between English and Latin is that the latter had no articles, and that singular bare nouns covered the use cases of both definite and indefinite articles in contemporary English. This can be illustrated by example (14), repeated below as (37).

(37) 51 erat autem turris excelsa in media civitate ad quam confugerant viri simul ac mulieres et omnes principes civitatis clausa firmissime ianua et super turris tectum stantes per propugnacula 52 accedensque Abimelech iuxta turrem pugnabat fortiter et adpropinquans ostio ignem subponere nitebatur

51 And there was in the midst of the city a high tower, to which both the men and the women were fled together, and all the princes of the city, and having shut and strongly barred the gate, they stood upon the battlements of the tower to defend themselves. 52 And Abimelech, coming near the tower, fought stoutly: and, approaching to the gate, endeavoured to set fire to it

If we look at the occurrences of turris (‘tower’) in example (37), we see that it appears without any explicit marking. The first occurrence, where turris is discourse new, is however marked in current English by an indefinite, and the two subsequent occurrences by a definite article, as can be seen in the translation.

Therefore, the major alternative to unus, given the assumption – as above – that unity cardinals have an existential entailment, was the singular bare form. Another possible competitor is ille N, which is the diachronic source of most of the definite articles in Romance.

What precise meaning should we assume for these entities? I suggest that the meaning of unus is identical to the meaning of one in English, and that the meaning of a bare singular corresponds to a NP with an indefinite article in English:

(38) unus = one

$\mapsto \lambda P\lambda Q\lambda w{\textstyle \vert \over {\textstyle x\vert P_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;Q_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;{\rm card}\lpar {P_w\cap Q_w} \rpar \,= \,1}}$

$\mapsto \lambda P\lambda Q\lambda w{\textstyle \vert \over {\textstyle x\vert P_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;Q_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;{\rm card}\lpar {P_w\cap Q_w} \rpar \,= \,1}}$(39)

$\emptyset $ = a

$\emptyset $ = a  $\mapsto \lambda P\lambda Q\lambda w{\textstyle \vert \over {\textstyle x\vert P_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;Q_w\lpar x \rpar }}$

$\mapsto \lambda P\lambda Q\lambda w{\textstyle \vert \over {\textstyle x\vert P_w\lpar x \rpar \comma \;Q_w\lpar x \rpar }}$

It is important to notice that semantically, the representation in (39) is perfectly compatible with both definite and indefinite uses as illustrated in (37); it merely does not require its uses to be one or the other.

I will justify the representations in (38)–(39) shortly, but let me first say a word about ille. Ille, like unus, has pronominal and adnominal uses, and appears 1498 times in the New, and 3097 times in the Old Testament. Among these occurrences, 241 attestations in the New Testament, and 154 in the Old Testament, are adnominal.Footnote 23 Unus appears 298 times in the New Testament, and 723 times in the Old Testament, of which respectively 121 and 432 are adnominal.Footnote 24 While the global frequency of ille is therefore roughly four times higher than that of unus, their adnominal uses are comparatively frequent. I therefore do not take ille to be a direct competitor to the bare nominal option (as a definite determiner would be), but rather to still be a demonstrative (which may be a competitor in a few, very circumscribed cases).Footnote 25

I will therefore assume that in Latin a bare noun is always available and salient, and that the use of unus has to be understood with respect to such a background. The explanations for the use of unus in Latin are thus basically the same as what we have already given for one in English, with the difference that there is no dedicated definite determiner, and there are no articles in general. Let us walk this through for the partitive use: the alternatives are the bare noun and unus N. Once again, we have to assume that the noun must be deaccented in the partitive (since it is given), and that we have to attribute an accent somewhere in the DP. A non-existent determiner cannot be accented, but it is not problematic to accent the determiner in unus N. Similarly, in a case of numeral contrast, the singular case-ending of a noun cannot be accented.

In order to discuss a non-partitive use, let us look at an example where unus appears discourse-initially. Consider (40) – which, while not coming from the Vulgate, exemplifies the same Christian Latin stratum.

Why would anybody want to use unus in such a context? The reasoning might go as follows: assuming that the bare noun is used either for a reference to an entity already in the common ground, or some new entity to be introduced, it might be inappropriate in the context of a creed. In the context of a predominantly polytheistic society, having a unique, presupposed entity satisfying the predicate god is bound to fail. On the other hand, without an explicit unus, there would probably be a possibility of reading it in a simple, existential way: there is at least one God I believe in. This, however, would not be sufficiently distinctive with respect to followers of Mithra, Jupiter, Isis, etc., and therefore, the unity cardinal becomes necessary.Footnote 26

The basic findings of this section are the following: assuming that unity cardinals do not carry any presupposition, and come with a cardinality meaning (as I have proposed in (27)) can explain their distribution in Latin and English with the added proviso that unity cardinals can be stressed, contrary to clitic or null determiners. In extending the game of same and different of Grønn and Sæbø (Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012), unity determiners may be found where definite and indefinite articles, and another cannot: in cases of partitive reference, and in cases that rely on contrast on tokens satisfying the same predicate, or more generally, cases that stress differences in cardinality.

One final concern is the major difference between Latin unus and English one, namely the possible distance between the unity cardinal and the element that it either contrasts with or has a partitive anaphora with. I do not know to which factor this should be attributed. I can see at least two candidates: First, the prevalence of gender marking in Latin could narrow down the potential antecedents in a way that is more difficult for a language like English where gender is at best a covert category. Second, admissible distance might be correlated with the overall frequency of determiners: it is possible that in a language without determiners, entities that are used with one achieve much higher salience than the same entities in a language with fully obligatory determiners, such as English. Should the first hypothesis be correct, all other things being equal, the admissible distance in German should be higher than in English; the second hypothesis predicts that null-determiner languages in general should pattern with Latin against English. The exploration of this issue must be left to further research.

4. Towards an explanation of the first steps in grammaticalization

My basic assumption is that an indefinite article is a unity cardinal that is used very often (and eventually may become obligatory in some contexts). During this process of becoming obligatory, it may diverge in its form from the cardinal (which occurred in English, and some varieties of German, but not in Romance languages). Given these assumptions, three basic questions are in need of an answer: i) what meaning change does this increase in use require? ii) why should the rate of use of the unity cardinal increase?; and iii) how is this increase related to the phonetic erosion of the unity cardinal?Footnote 27

The important background to note is the following: under the assumptions we have made in this article, even though a unity cardinal comes with strictly more meaning than a bare form (or than an indefinite article, in languages that have one), given standard use cases for those forms, it will rarely be the case that the context makes the use of the cardinal inappropriate or even false. Most of the time, its use will constitute more signaling effort than is strictly necessary. Such cases of unclear motivation are attested in the use of unus vs. the bare version, as in (close-to) minimal pairs like the following:

It should be clear that there is no truth-conditional difference between the two versions in (41); however, there does not seem anything fundamentally wrong with employing the unity cardinal.Footnote 28

On the other hand, there will also be few contexts which would require the meaning of a bare singular (or an indefinite article), as opposed to the meaning of the unity cardinal. For instance, there is nothing wrong in principle in using a unity cardinal in a predication context (although it has some effects we will discuss in section 4.2 below):

(42) ‘Rampage’ is one stupid ass movie.Footnote 29

Similarly, the existence of plural forms is not incompatible with a cardinal interpretation. Notice that many unity cardinals do allow for plurals (think of English ones), and that, if the semantics for unity cardinals proposed in Reference SchadenSchaden (To appear (b)) is correct, there is indeed nothing in the meaning of a unity cardinal that would be intrinsically incompatible with pluralization. Therefore, the presence of a plural form of a unity cardinal is not ipso facto an indicator of a highly advanced indefinite article.Footnote 30

Thus, the major checks on the frequency of the unity cardinal are not the intrinsic meaning of the unity cardinal nor the contexts in which it appears, but rather speaker effort and the effect a speaker wants to obtain by choosing a more elaborate signal.

That being said, let us address the three questions.

4.1 Meaning change: weakening the hard upper bound

If the results of this article are to be trusted, one N is only distinct from the indefinite article by having a cardinality meaning attached to it, and it triggers antipresuppositions which make it apt to appear in partitive and contrastive environments, which depend crucially on its not being a clitic. Obviously, both the antipresuppositions and the cardinality component no longer arise in the same way with an indefinite article like the contemporary English a. Remember also from (30) that the cardinal meaning of unity cardinals is special in that it has a hard upper bound, and not a soft upper bound like all other cardinals.

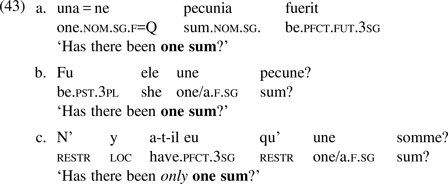

Let us fast forward a few centuries. Carlier (Reference Carlier2001 Reference Carlier and Arteaga2013) observes that Latin unus in a restrictive sense (that is, uses roughly conveying ‘a single N’) is translated in Old French generally by uns, whereas from the Middle French period on, there generally is a additional restriction (≈ ‘only’) added to it:Footnote 31

This change in translation is clearly significant, but there are two possible ways to interpret it. Carlier (Reference Carlier and Arteaga2013: 47) takes additional restrictors to indicate that un is no longer a cardinal. Her reasoning goes as follows: in Old French, where the numeral value was still dominant, the translators felt no need to add a restriction, whereas in more recent varieties of French, where we can assume un to be an indefinite article, there is a need for adding such a restriction, in order to obtain a cardinality interpretation. Therefore, the presence of a restriction is an indicator of a loss of cardinality status and meaning, in a two-step process from cardinal to indefinite article. However, this does not necessarily follow. A second, and by far more conservative interpretation of the same facts (under the assumption of a gradual transition from “hard upper bound cardinal” to indefinite article) is that the rising frequency of restrictors simply indicates that the upper bound constraint was softened, and that the unity cardinal aligned with other cardinals (thus, that the uses of one vs. only one exactly parallels, e.g., the use of two vs. only two), and does not indicate a complete loss of cardinal status. The basic issue here is that we have (at least) a three-step transition, from hard upper bound cardinal to soft upper bound cardinal, and then from soft upper bound cardinal to indefinite article.

How can we explain the disappearance of the hard upper bound? Unless one assumes that unity cardinals are fundamentally different from all other cardinals, this is likely due to an antipresupposition in languages which have a singular-plural system, since the unity cardinal has a competitor in the singular bare noun or indefinite article which all other cardinals lack.Footnote 32 Therefore, if the unity cardinal is chosen over the default (bare or indefinite article), which also signals a singular entity, this may signal higher confidence, and the ‘exactly’ interpretation will arise, and the hard upper bound will be derived.

However, once the use of the cardinal becomes more frequent, and a hearer no longer expects the of use of the alternative form, the hard upper bound disappears, and the unity cardinal aligns with other cardinals in obtaining a soft upper bound.

4.2 The Increase in frequency

Now, let us get back to the first question: why should the frequency of use of a unity cardinal rise in the first place?

When looking at examples like (41b) or (42), it seems probable that emphasis has a role to play: even in the absence of a clear truth-conditional difference, if there is emphasis, the unity cardinal is used; without emphasis, the alternative (bare noun or indefinite article) is used. It may appear that the notion of emphasis is a poor choice underlying a formal model of language change, but Ahern and Clark (Reference Ahern and Clark2017) have already worked out a model explaining such a process for Jespersen's cycle. The function of emphasis in Ahern and Clark (Reference Ahern and Clark2017: 8ff.) is that emphasis sharpens a standard of evidence, and that using an emphatic element signals that the speaker has better evidence than normal for the assertion. Carrying over this idea to our examples would mean that a speaker calling Rampage ‘one stupid-ass movie’ rather than ‘a stupid-ass movie’ indicates a higher degree of confidence and evidence with respect to the judgment. Similarly, for (41b), the idea is that a speaker asserting ‘one cubit’ signals higher precision and evidence than signaling simply the bare ‘cubit’.Footnote 33 Whether the case at hand meets a high enough standard of evidence to warrant an explanation based on emphasis must be left for further investigation.

The increase of the emphatic form (in our case, the unity cardinal, as opposed to the non-emphatic bare form) can then be explained as an inflation process – which is a rather standard way of conceiving the dependence between meaning and frequency.Footnote 34 In a nutshell, the idea can be stated as follows: in having an emphatic and a non-emphatic form, there will be a partition of degrees of emphasis involved in an assertion: below some threshold x, the bare form will be used, whereas above this threshold, the unity cardinal will be used. Therefore, signaling emphasis provides for a rhetorical effect, which a hearer reacts to.Footnote 35 However, speakers are assumed to have a bias which drives the threshold down over time, such that the rhetorical effect is more and more diminished.Footnote 36 Eventually, this will lead to the disappearance of the non-emphatic, bare variant, and the optional unity cardinal will have become an obligatory indefinite article.Footnote 37

4.3 Phonetic erosion and scope issues

Finally, let us come to the problem of phonetic erosion. As I have pointed out, this is not a necessary process, but one can make a case that in languages like German or in Romance languages, the indefinite article is a clitic version of the cardinal. The old form can, however, still be used as a cardinal. How can this be accounted for?

Part of the answer to this question is related to some rather puzzling facts about scope dependencies. As we have seen, unity cardinals can appear without any problem within the scope of a quantifier. However, according to the standard classification of Heine (Reference Heine1997), narrow scope readings disappear in the development of the indefinite article. This seems somewhat paradoxical if one is not willing to assume that a form acquiring a new meaning will necessarily lose the old meaning. I will take the position here that what is at stake is not the specific vs nonspecific readings, but actually the issue of the unity cardinal occurring under the scope of another scope-bearing element (be that a modal, or an adnominal universal quantifier).

Note that the narrow scope indefinite configuration (henceforth ![]() ${\bullet} \exists $) is an unmarked configuration with respect to the wide-scope configuration (henceforth

${\bullet} \exists $) is an unmarked configuration with respect to the wide-scope configuration (henceforth ![]() $ \exists {\bullet} $), in the sense that the latter is strictly more informative than, and constitutes a special case of, the former.Footnote 38 Consider (44):

$ \exists {\bullet} $), in the sense that the latter is strictly more informative than, and constitutes a special case of, the former.Footnote 38 Consider (44):

(44) Every citizen worships a god.

a. Narrow scope: For every citizen x: there exists a god y such that x worships y

b. Wide scope: There exists a god y such that, for every citizen x, it is true that x worships y.

Whenever (44b) is true, then (44a) will also be true; however, if (44a) is true, it might still be the case that (44b) is false (say, if I worship Isis, and you worship Mithras). Therefore, (44b) asymmetrically entails (44a), and we have a Horn-scale between these two meanings, where ![]() ${\bullet} \exists $ is the weak term (unmarked), and

${\bullet} \exists $ is the weak term (unmarked), and ![]() $\exists \bullet $ the strong (marked) term.

$\exists \bullet $ the strong (marked) term.

It has often been observed that marked forms tend to associate with marked meanings, and that unmarked forms associate with unmarked meanings (a phenomenon known as the division of pragmatic labor, see, e.g., Horn Reference Horn1989: 197f.). Therefore, associating a marked form (that is, unus N) to the marked meaning ![]() $\exists \bullet $ and the unmarked form (that is, the bare noun) with the unmarked meaning

$\exists \bullet $ and the unmarked form (that is, the bare noun) with the unmarked meaning ![]() ${\bullet} \exists $ would be the expected outcome, and form a so-called Horn-strategy, whereas associating the unmarked bare form with the marked meaning (and vice versa) would correspond to an Anti-Horn strategy (see, e.g., van Rooy Reference van Rooy2004). Let us see how we can derive this in the framework we have been using so far.

${\bullet} \exists $ would be the expected outcome, and form a so-called Horn-strategy, whereas associating the unmarked bare form with the marked meaning (and vice versa) would correspond to an Anti-Horn strategy (see, e.g., van Rooy Reference van Rooy2004). Let us see how we can derive this in the framework we have been using so far.

Notice first that using a definite article in order to signal wide scope would not only correspond to ![]() $\exists \bullet $, but require the entity having wide scope to be presuppositional. Another, comparatively, would require that all elements in the discourse be different (see Grønn and Sæbø Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012: 90). Therefore, both of these forms can be excluded as candidates in potentially marking scope ambiguities. So, in case of a narrow-scope configuration, the most unmarked remaining form should be used, which is the bare form. On the other hand, in the case of a non discourse-linked wide-scope configuration, if this is deemed to be important enough to be marked, we should then reach for some marked form with a sufficiently compatible meaning. Once again, the unity cardinal is a plausible candidate for this use.

$\exists \bullet $, but require the entity having wide scope to be presuppositional. Another, comparatively, would require that all elements in the discourse be different (see Grønn and Sæbø Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012: 90). Therefore, both of these forms can be excluded as candidates in potentially marking scope ambiguities. So, in case of a narrow-scope configuration, the most unmarked remaining form should be used, which is the bare form. On the other hand, in the case of a non discourse-linked wide-scope configuration, if this is deemed to be important enough to be marked, we should then reach for some marked form with a sufficiently compatible meaning. Once again, the unity cardinal is a plausible candidate for this use.

This prediction has, however, a loophole, allowing for a narrow-scope interpretation of the unity cardinal in one context. There is a second configuration which is asymmetrically entailed by ![]() ${\bullet} \exists $, namely if there is some importance to the fact that not only the relation is

${\bullet} \exists $, namely if there is some importance to the fact that not only the relation is ![]() ${\bullet} \exists $, but also, that the cardinality of each dependent element is exactly one.

${\bullet} \exists $, but also, that the cardinality of each dependent element is exactly one.

(45) For each citizen x, there is exactly one god y such that x worships y.

Once again, whenever (45) is true, then (44a) will also be true, but (44a) being true does not require (45) to be true (say, if you worship Mithras alone, but I worship Isis and Serapis). Therefore, there is a second Horn-strategy available.

If the use of Horn-strategies to explain scope dependencies is on the right track, this gives us the following empirical prediction: in the beginning stages of grammaticalization, if a unity cardinal is used, the speaker should target a marked interpretation. That is, we should not observe narrow-scope readings of a unity-cardinal, unless we have a restrictive meaning, in the sense of only one N. Should such narrow-scope readings be present, this would falsify the Horn-strategy explanation.

Notice, however, that there is a well-known descriptive generalization in the grammaticalization framework that lends support to the Horn-strategy hypothesis. We have the impression that, at some stage in its diachronic development (that is, stages 2–3 in Heine's scale), an indefinite article loses the possibility of taking narrow scope. Marking wide scope by means of a unity cardinal is just one way of giving a marked form a marked reading. However, the cardinality component of a unity cardinal is not causally related to the wide-scope reading (although it does nothing to impede it). Yet, in case of a narrow-scope reading insisting on the cardinality one, the semantic difference between the bare form and the unity cardinal is stressed. This would also mean that one should expect the determiner in the narrow scope context to always be accented, and therefore be perceived as the numeral (and it should not be able to undergo phonetic erosion in this context). Since the wide-scope marking does not intrinsically depend on any meaning component of the cardinal, one would not expect it to be systematically accented, and therefore it should be more susceptible to phonetic erosion in this use. In the long run, this could then lead to a dissociation between a cardinal (which is always accented) and an indefinite article (which is not).

Let me sum up the core idea defended in this section: there are very few contexts which would semantically require or prohibit a unity cardinal (as opposed to a bare singular, or an indefinite article), so its use comes down to whether the speaker is motivated to use a more marked form where it is possible but not strictly necessary. The motivation for use of the unity cardinal has been tentatively identified as emphasis, of which Ahern and Clark (Reference Ahern and Clark2017) have provided a formalization. I have also introduced an explanation of how use can erode this emphasis. I have tried to demonstrate how the avoidance of indefinite articles in narrow-scope contexts can come about, and how this can also give us a clue about the diachronic process of the separation of a single form into two different forms (unity cardinal vs. indefinite article). While these ideas are still speculative, they provide a starting point from which a fully formal pragmatic and usage-based account of the extension of the use of unity cardinals can be explored, and where fully formal diachronic models of language change can be applied.

5. Conclusions and perspectives

In the present article, I have tried to complement the existing literature on the grammaticalization of indefinite articles by describing the discourse behaviour of unity cardinals in English and Latin. I have argued that this is a necessary endeavour because – while we have a good idea of the semantics of the indefinite article in languages like English (which is close to the diachronic endpoint of the grammaticalization process), and we also have a general understanding of the vector of change – the discourse behaviour of unity cardinals has so far not been investigated in sufficient detail. Therefore, we lack a solid baseline from which we can judge further developments. I have provided a formal account of the distribution of these cardinals based on the work by Grønn and Sæbø (Reference Grønn and Sæbø2012) and Amsili and Beyssade (Reference Amsili and Beyssade2016). Empirically, I have tried to show that ‘innovative’ uses of unus in the Vulgate correspond quite closely to standard uses of unity cardinals, which I have taken to be exemplified by English one. Therefore, I have concluded that – for the Latin of the Vulgate – there is no need to assume that any kind of grammaticalization process has taken place. I have also tried to sketch by which pragmatic procedures the early stages of grammaticalization can be explained.

Contrary to most preceding analyses, but in line with Pozas Loyo (Reference Pozas Loyo2010), this account makes little use of semantic changes in a strict sense, at least for the initial stages of grammaticalization, but stresses factors such as the ability to be accented as important for the diachronic development of unity cardinals. Therefore, it is more in line with inflation-based approaches to language change like Schaden (Reference Schaden2012) and Ahern and Clark (Reference Ahern and Clark2017), and may open the analysis of the diachronic development of indefinite articles in this direction.

A Note on methodology: The Vulgate as a sacred, and translated text

This article has examined the use of unus in the Vulgate in its own right, and as a genuine (late) Latin phenomenon. Yet, to what degree does the use of unus in the Vulgate represent an actual Latin usage, or does it rather reflect a phenomenon of the source languages (or texts)? This is an extremely difficult question to answer in a general way (see, e.g., Calboli Reference Calboli2009 and Rubio Reference Rubio2009 for the more general question of the influence of Greek and Semitic languages on Latin), but the existing literature provides some answers.

A first potential worry stems from the fact that the Vulgate is a translated work. Since it is additionally an example of a holy (and divinely-inspired) text, a translator might be tempted even more to calque features from the source text that do not correspond closely to the target language's grammar. However, unlike other translations (e.g., into Syriac, where lost Greek originals can be reconstructed from the Syriac version), Latin translations are no word-by-word renderings of their Greek source text (see Houghton Reference Houghton2016: 143ff. on this issue).

A second problem concerns the source language of the translation. While for the New Testament, it is necessarily Greek, it is not that clear that the unique source for the Old Testament is Hebrew (and, to a lesser degree, Aramaic): Jerome's fluency in Hebrew has often been questioned (see Newman Reference Newman2016), and it is certainly the case that he was familiar with the (Greek) Septuagint version of the Old Testament before he knew the Hebrew original.

And even with respect to the New Testament, Jerome did not start from scratch: there were several preexisting Latin translations, collectively known as the Vetus Latina (for a description of the different manuscripts and their textual relations, see, e.g., Burton Reference Burton, Ehrman and Holmes2013, Houghton Reference Houghton2016).

Finally, there is also variation in the Greek source texts themselves, which have been classified into several “text types” (see Metzger and Ehrman Reference Metzger and Ehrman2005: 276ff.), even though the well-foundedness of these types has been called into question recently (see, e.g., Burton Reference Burton, Ehrman and Holmes2013, Houghton Reference Houghton2016)). The important point here is that Greek sources also vary with respect to the use of heîs (which is the Greek unity cardinal one). The edition of the Greek New Testament in PROIEL (see Haug and Jøndal Reference Haug, Jøndal, Sporleder and Ribarov2008) is based on recent critical editions of the Bible (see Aland et al. Reference Aland2012), whereas the Greek Orthodox Church liturgy uses a different recension (manuscripts in this tradition form the “Byzantine text type”), which is also the base of Erasmus's Textus Receptus (see Metzger and Ehrman Reference Metzger and Ehrman2005: 276–280). The Greek Orthodox majority text shows a heîs in a few passages, where other recensions lack it.Footnote 39

As an illustration, consider the following versions of the beginning of John (6:9), where (46a) is transliterated from Aland et al. (Reference Aland2012), whereas (46b) is transliterated from Hodges and Farstad (Reference Hodges and Farstad1985: 308), and where (46c) is from the Vulgate: