1. Introduction

A relative clause (RC) is a type of subordinate clause that modifies a nominal (Lehmann Reference Lehmann1986: 664).Footnote 1 Relative clauses seem to be difficult structures to comprehend and to form for both first and second language learners (Izumi Reference Izumi2003: 286). Due to the inherent complexity of RC structures and the noticeable difficulties in the acquisition of RCs, a considerable amount of research has been conducted to investigate linguistic features of RCs in typologically different languages and to explore the cognitive processes involved in their acquisition (e.g., Prideaux and Baker Reference Prideaux and Baker1986, Hamilton Reference Hamilton1994, Sadighi Reference Sadighi1994, Izumi Reference Izumi2003, Hawkins Reference Hawkins2007, Ozeki and Shirai Reference Ozeki and Shirai2007, Brandt et al. Reference Brandt, Diessel and Tomasello2008, Brandt et al. Reference Brandt, Kidd, Lieven and Tomasello2009, Hopp Reference Hopp2014, Kim and O'Grady Reference Kim and O'Grady2015).

A number of factors have been identified as playing a role in RC acquisition in L2 contexts: (i) general learnability, based on the assumption of a fixed natural order of acquisition of RCs, (ii) learners’ previously learned language(s), and (iii) input exposure, frequency, and experience.

Regarding the natural order of acquisition of RCs, several claims have been made. Two prominent hypotheses are the Noun Phrase Accessibility hypothesis (NPAH) proposed by Keenan and Comrie (Reference Keenan and Comrie1977) and the Perceptual Difficulty hypothesis (PDH) proposed by Kuno (Reference Kuno1974). It should be noted that the NPAH was originally a typological investigation of RCs and was not meant to predict the acquisition order of RCs, but later it was hypothesized that the NPAH reflects the order of difficulty in acquisition of RCs (Gass Reference Gass1979, Eckman et al. Reference Eckman, Bell and Nelson1988, Doughty Reference Doughty1991).

The NPAH is based on an extensive comparative study of RC structures in more than fifty typologically different languages. Keenan and Comrie pay attention to the relativizability of noun phrases and focus on the syntactic functions of the relativized NP in the relative clause. They state that the relativizability of an NP is linked to its syntactic position in the RC, and that some syntactic positions are more accessible to relativization than others. In their NPAH, Keenan and Comrie (Reference Keenan and Comrie1977: 66) propose a universal hierarchy of relativization, known as the accessibility hierarchy. According to the NPAH, the subject position (S) is most accessible to relativization, followed by the direct object (O) and other syntactic functions. Hence, the hierarchy hypothesized by the NPAH, from the most accessible position for relativization to the least accessible one, is (S) > (O) > (IO) > (OBL) > (GEN) > (OCOMP) (where > = more accessible than). As Keenan and Comrie state, subject is the grammatical position that all languages must be able to relativize. With regard to the markedness relationship in different RC types, they claim that if a language allows the formation of an RC of a given position in the accessibility hierarchy, it also allows the formation of RCs of all higher positions, while the converse is not true. The NPAH “reflects the psychological ease of comprehension” (Keenan and Comrie Reference Keenan and Comrie1977: 88), meaning that it is harder to understand RCs formed on lower positions than ones on higher positions. In other words, RCs formed from subject positions (henceforth, subject relatives) are the easiest RC types to comprehend, learn, and produce (Izumi Reference Izumi2003: 288).

A number of studies have reported that L2 learners of English find subject relatives easier to comprehend and produce than object relatives (Gass Reference Gass1979, Reference Gass, Scarcella and Krashen1980,Reference Gass, Hynes and Rutherford1982; Eckman et al. Reference Eckman, Bell and Nelson1988; Doughty Reference Doughty1991; Wolfe-Quintero Reference Wolfe Quintero1992; Hamilton Reference Hamilton1994). Several hypotheses have been proposed to account for this asymmetry. While some scholars believe that the asymmetry is attributable to structural factors, as in the Structural Distance Hypothesis (O'Grady et al. Reference O'Grady, Miseon and Miho2003), others favour a linear distance effect, suggesting the Linear Distance Hypothesis (Tarallo and Myhill Reference Tarallo and Myhill1983, Hawkins Reference Hawkins1989).

The Linear Distance Hypothesis was first put forward by Tarallo and Myhill (Reference Tarallo and Myhill1983), and by Hawkins (Reference Hawkins1989) to explain L2 learners’ preference for subject relatives over object relatives in learning English as an L2 (as cited in O'Grady et al. Reference O'Grady, Miseon and Miho2003: 434). According to this hypothesis, the L2 learners’ preference for subject relatives is due to the shorter linear distance between the subject and the subject gap, as opposed to the longer distance between the direct object and the direct object gap: the longer the distance between the relativized element and the gap, the more difficult the comprehension of the relative clause. Linear distance is measured by counting the number of intervening words between the head noun and the gap (see example (1) taken from O'Grady et al. (Reference O'Grady, Miseon and Miho2003: 434)).

(1)

a. Subject relative: the man [that ___ likes the woman]

Linear distance between the head noun and the gap = 1 word

b. Object relative: the man [that the woman likes ___ ]

Linear distance between the head noun and the gap = 4 words

Although L2 learners’ preference for subject relatives is said to be caused by a linear distance effect, O'Grady et al. (Reference O'Grady, Miseon and Miho2003) believe that the preference is attributable to structural factors. O'Grady et al. (Reference O'Grady, Miseon and Miho2003) conducted a study on Korean, which is a head-final language in which subject gaps in RCs are more distant from the head noun than object gaps. According to the Linear Distance Hypothesis, in Korean, subject relatives would be more difficult to comprehend. However, the opposite was found to be the case, as Korean learners showed a strong preference for subject relatives. O'Grady et al. (Reference O'Grady, Miseon and Miho2003: 435) proposed the Structural Distance Hypothesis as a means of measuring “the depth of embedding of the gap”, and calculated the distance by counting the number of intervening maximal projections (see example (2) taken from O'Grady et al. (Reference O'Grady, Miseon and Miho2003: 435)). As the structural distance between the head and the gap is shorter in subject relatives than object relatives, the prediction of the Structural Distance Hypothesis is that the comprehension of subject relatives would be easier than object relatives. In the Korean language, a subject gap is structurally closer to the head although a subject gap is linearly more distant from the head than a direct object gap. That explains why English-speaking learners of Korean find subject relatives far easier than direct object relatives (O'Grady et al. Reference O'Grady, Miseon and Miho2003: 442).

(2)

a. Subject relative: the man that [S___ likes the woman]

number of nodes between the head and the gap = 1 (S)

b. Object relative: the man that [S the woman [VP likes ___ ]]

number of nodes between the head and the gap = 2 (VP, S)

Another hypothesis put forward to account for processing difficulty of RC types is the Perceptual Difficulty Hypothesis (PDH), which proposes that the interruption in the flow of a sentence caused by an intervening clause is one of the contributing factors of processing difficulty in RCs. The PDH holds that the position of the RC, whether in the middle of the matrix clause or attached to the clause edge, determines the processing of sentences containing RCs. According to Kuno (Reference Kuno1974), limitations of human working memory cause difficulty in the processing of sentences containing centre-embedded RCs. If an RC appears in the middle of the matrix clause, it interrupts the flow of the matrix clause by separating the matrix subject from its verb. In contrast, RCs which are on the periphery of the matrix clause do not cause any interruption. Kuno assumes that interruption is an obstacle to the comprehension of RCs; therefore, centre-embedded RCs interfere with language processing and make the comprehension of the sentence more difficult in comparison with RCs positioned on the right/left. Thus, according to the PDH, sentence (3a) is perceptually more difficult to process than sentence (3b).

(3)

a. The person [who lives next door] works at the library.

b. I know the person [who lives next door].

According to Doughty (Reference Doughty1991: 439), the PDH, “while intuitively appealing, has not found consistent empirical support”, and “there have been no acquisition studies conducted that have emanated from it.” Her claim was refuted by Izumi, a proponent of the PDH. Izumi (Reference Izumi2003: 292) states that the PDH “is based on a sound theoretical foundation”, and has been experimentally supported by studies conducted by Cook (Reference Cook1973), Schumann (Reference Schumann, Scarcella and Krashen1980), Prideaux and Baker (Reference Prideaux and Baker1986), and Bates et al. (Reference Bates, Devescovi and D'Amico1999). Izumi believes that the PDH needs closer attention and more in-depth investigation, particularly for L2s, as it has not received sufficient attention in second language acquisition studies.

While the NPAH predicts the accessibility order of RCs by focusing on the syntactic functions of the element relativized in the RC (henceforth, NPrel roles), the PDH predicts the ease of processing of RCs by focusing on the position of the RC in the matrix clause. Thus, the syntactic functions of the NPs in the matrix clause (henceforth, NPmat roles) are taken into consideration in the PDH, namely: subject (S), direct object (O), prepositional phrase object (PPO), predicate nominal (PN), and predicative complement in existential clause (EX) (Fox and Thompson Reference Fox and Thompson1990). Examples (4a–4e) illustrate each type of NPmat role.

(4)

a. (S): Many people [who are in prisons] have big financial problems.

b. (O): Man manufactured gigantic planes [which are able to carry hundreds of people and loads of cargo].

c. (PPO): We live in the modern world [which is dominated by science and technology].

d. (PN): Pollution is an environmental problem [that endangers humans’ lives].

e. (EX): There are several sources [that cause water pollution].

The NPAH and the PDH are based on different categorization and motivation: the NPAH has a psychological motivation, categorizing RC types based on the syntactic functions of the NP within the RC, whereas the PDH has a memory-related processing motivation, focusing on the processing interruption of RCs created by the position of the RC in the matrix clause. It is assumed in this article that placing different RC types outlined in the NPAH in all positions relative to the matrix clause will shed more light on the accessibility order of RCs in L2 contexts.

Regarding the natural order of acquisition of RCs, it is expected that the accuracy rate of RCs formed by Kurdish Sorani-speaking learners of English is affected by: (i) the syntactic function of the relativized NP, and (ii) the location of the RC in the matrix clause. In other words, it is assumed that the predictions of the NPAH and the PDH will be borne out by data collected from the Kurdish Sorani-speaking learners of English. If the data provide support for both the NPAH and the PDH, the results will support the findings of previous studies like Izumi (Reference Izumi2003: 316–317), according to which the NPAH and the PDH are complementary hypotheses rather than competing ones.

In addition to theories that assume a natural order of acquisition and processing difficulty of RCs, there are theories assuming that syntactic transfer from the earlier learned language(s) impacts acquisition of RCs in the language being learned.

The theory of language transfer can be considered as having undergone three stages (Yi Reference Yi2012: 232). The first stage was from the 1950s throughout the 1960s, when structural linguistics and behavioural psychology were dominant. In 1957, the contrastive analysis hypothesis (CAH) was proposed, according to which the difficulties language learners will have in the target language are entirely predictable through comparison of the native language and target language. The CAH was severely criticised by cognitivists in the late 1960s. In consequence, language transfer entered into its second stage, from the 1970s to the 1980s, influenced by Chomsky's universal grammar. Dulay and Burt (Reference Dulay, Burt and Richards1974) claimed that L1 transfer has a trivial role in L2 acquisition and that L2 acquisition is facilitated by universal principles. At the third stage, from the 1980s, different theories on L1 transfer have been proposed. The theories have considered (i) the state of the L2 acquisition (the initial, developmental, or final stages), (ii) the extent to which linguistic properties of L1 are assumed to impact L2 (full, partial, or no transfer), and (iii) the extent to which universal grammar regulates L2 representations (White Reference White and Archibald2000). In the present study, the L1 and L2 differ in terms of how RCs are formed, providing the means to further explore effects of L1 transfer.

2. Relativization in Kurdish Sorani

Kurdish is one of the Indo-Iranian languages with subject-object-verb (SOV) word order. Kurdish consists of three main dialect groups, known as Central Kurdish, Northern Kurdish, and Southern Kurdish. Kurdish Sorani, “which has been used in the literature to refer to all Central Kurdish subvarieties”, is in fact the main subset of Central Kurdish (Anonby et al. Reference Anonby, Mohammadirad, Sheyholislami, Gündoğdu, Öpengin, Haig and Anonby2019: 27). Sorani, with around 10 million native speakers, is mainly spoken in Iran and the Kurdistan region in Iraq. This language permits post-nominal RCs, headless RCs, and extraposed RCs. This study focuses on post-nominal RCs.

Post-nominal relative clauses in Kurdish Sorani are introduced by the invariant marker ka, which is used regardless of the animacy, gender, function, or number of the noun modified by the relative clause. Ka is equivalent to who, which, or that in English. The omission of ka is allowed in restrictive RCs when the NP that has been relativized functions as object in the RC (see example (5). Omission of ka in subject relatives is also allowed in Kurdish Sorani, although it rarely occurs (see example (6) (Thackston Reference Thackston2006: 72–73, Kim Reference Kim2010: 88).

(5) Brâdar-aka-ī [(ka) to da-y=nâs-i] khalât-ek-i bo henâ-m.

friend-def.sg-ez rel you asp-res=know-prs.2sg gift-indf-3sg.a for brought-I.

‘The friend (that) you know brought me a gift.’

(6) Brâdar-aka-ī [(ka) da-m=nâs-e] khalât-ek-i bo henâ-m.

friend-def.sg-ez rel asp-me=know-prs.3sg gift-indf-3sg.a for brought-I.

‘The friend who knows me brought me a gift.’

It should be noted that the omission of ka in both subject and object restrictive RCs can only occur if the ezafe marker (-ī in examples 5 and 6) is attached to the end of the modified head noun. The ezafe marker, which is one of the most frequent grammatical morphemes in most of the West Iranian languages, occurs in several overlapping functions (Haig Reference Haig, Yap, Grunow-Hårsta and Wrona2011). One of its functions is to introduce a restrictive relative clause by linking the head noun to its post-nominal RC. The ezafe marker cannot be attached to NPs relativized by a non-restrictive RC. When the ezafe marker links the restrictive RC to the head noun, ka can be optionally omitted in both object and subject relatives (see examples 5 and 6). This means that a restrictive RC in Kurdish Sorani could sometimes be linked to the head noun solely by an ezafe marker, without the occurrence of the invariant marker ka. However, when no ezafe marker occurs, the use of ka is obligatory (example 7).

(7) Brâ-ka-m [ka doyne hât] khalât-ek-i bo henâ-m.

brother-def.my rel yesterday came-pst.3sg gift-indf-3sg.a for brought-I

‘My brother who came yesterday brought me a gift.’

In addition, restrictive RCs in Kurdish Sorani can be formed by using the demonstrative determiner aw before the relativized NP. In such cases, the demonstrative clitic -e, (pronounced /–æ/), a definiteness marker, is attached to the end of the NP. Thus, the structure would be aw … …-e, called the demonstrative determiner complex by Öpengin (Reference Öpengin2016: 112) (see example 8a). All Kurdish Sorani RCs which can be formed using the demonstrative determiner aw…-e, can also be formed using aw preceding the head noun, followed by the ezafe marker (see example 8b). This means that the ezafe marker -ī can co-occur with the demonstrative determiner aw and with the demonstrative clitic -e.

(8)

a. Aw brâdar-e [ka doyne hât] khalât-ek-i bo henâ-m.

dem friend- dem.cl rel yesterday came-pst.3sg gift-indf-3sg.a for brought-I

‘The friend who came yesterday brought me a gift.’

b. Aw brâdar-ī [(ka) doyne hât] khalât-ek-i bo henâ-m.

dem friend- ez rel yesterday came-pst.3sg gift-indf-3sg.a for brought-I

‘The friend who came yesterday brought me a gift.’

Kurdish Sorani lacks articles, and the ezafe marker is generally used to mark definiteness of the head noun. There is no semantic difference between RCs with the ezafe marker and RCs with the demonstrative determiner aw. Both types denote uniqueness of the head noun modified. While the type of uniqueness differs slightly, it is otherwise exactly like English, in which nouns with the denote the uniqueness of the noun “in the discourse”, and nouns with that denote the uniqueness of the noun “in the immediately salient situation” (Ionin Reference Ionin, Baek, Kim, Ko and Wexler2012: 69).

An important factor regarding post-nominal RCs in Kurdish Sorani is the use of resumptive pronouns, which restate the relativized NP. While in Standard English, a gap resulting from wh-movement is left in subject and object relatives, Kurdish Sorani permits the use of resumptive pronouns in the construction of some types of RCs. When an NP relativized in Kurdish Sorani has the syntactic function of object, a resumptive pronoun is used (see example 9). However, the use of resumptive pronouns is not permitted in subject relatives.

(9) kteb-aka- ī [(ka) aw da-y= kr-eFootnote 2] zor baš-a.

book-def.sg-ez rel s/he asp-it.res=buy.prs-3sg very good-is

‘The book s/he is buying is very good.’

Studies on Persian, a language with similar linguistic properties to Kurdish Sorani and in which the use of resumptive pronouns in the construction of RCs is permitted, have shown that Persian learners of English transfer the use of resumptive pronouns to English RCs (Enjavinezhad and Paramasivam Reference Enjavinezhad and Paramasivam2014, Marefat and Abdollahnejad Reference Marefat and Abdollahnejad2014). As Kurdish Sorani is typologically close to Persian, it is likely that similar results will be obtained for this language.

3. Objectives of the study

Predictions derived from the NPAH and the PDH have been tested in a variety of languages in second language settings using different types of elicitation tasks. A number of studies have been conducted examining the production of RCs by learners of English with different first languages. However, to the best of my knowledge, no study has been carried out which investigates the production of English RCs by Kurdish Sorani speakers.

Kurdish Sorani is a noteworthy language to study. SOV word order is maintained in subject relatives, while it changes to OSV in object relatives. Thus, Kurdish Sorani and English have the same word order in object relatives, while differing in subject relatives. It is therefore of interest to investigate whether this difference in word orders affects the acquisition of English RCs by Kurdish Sorani-speaking learners of English. Furthermore, Kurdish Sorani permits resumptive pronouns in the construction of object relatives, disallowed in Standard English. It is also of interest to discover whether Kurdish Sorani-speaking learners of English transfer the possibility of resumptive pronouns from their L1 to L2. Such questions motivated the present study.

For practical reasons, this study deals with the first two positions in the NPAH (i.e., subject and object relatives), which are assumed to be the most accessible and the most frequently used types of RCs. Although the study focuses only on two types of relatives, it aims to consider the interaction between the syntactic functions associated within the RC and within the matrix clause. Therefore, the syntactic functions of the NPs in the matrix clause (NPmat roles), and the syntactic functions of the coreferent within the RC (NPrel roles) are investigated. This means that subject and object relatives are examined in matrix clauses in which the NP has the function of either subject, object, predicate nominal, or predicative complement of an existential clause. The present study aims to:

(i) Establish hierarchies of use of subject and object relatives with different NPmat roles using two different elicitation tasks

(ii) Compare the hierarchies obtained from each task to one another and to the hierarchies proposed by the NPAH and the PDH

(iii) Explore whether the attachment of subject and object relatives in different NPmat positions affects the rate of accuracy in the formation of subject and object relatives

(iv) Examine whether the errors of Kurdish Sorani-speaking learners of English in the formation of English RCs are the result of L1 transfer, such as the differences in word orders in RCs or the use of resumptive pronouns.

4. Methodology

The following sections set out the design and methodological framework of the study.

4.1 Participants

The participants of the study were 45 native speakers of Kurdish Sorani who were studying English at English language institutes in the North-West of Iran. There were 20 male and 25 female participants aged between 21 and 30 years old. None of the participants had been to English-speaking countries and none of them had contact with native English speakers. Their teachers were also non-native speakers. The participants were assessed for their level of English proficiency with a preliminary placement test developed by Cambridge University Press, conducted prior to the experiment. The mean of the scores of the placement test was 75.87 out of 120, with a range of 56 to 94. The placement test was provided by the language institute where the study was carried out.

4.2 Elicitation tasks

Both a sentence combination test and a translation test were employed. In designing the items for each test, the NPmat roles of as well as the NPrel roles were taken into consideration. Thus, the following RC types were included in the design of the test items: (i) S-S relatives, (ii) O-S relatives, (iii) PN-S relatives, (iv) Ex-S relatives, (v) S-O relatives, (vi) O-O relatives, (vii) PN-O relatives, and (viii) Ex-O relatives (see Tables A1 and A2 in Appendix)Footnote 3. Examples (10)–(17) below illustrate each type.

(10) (S-S): The girl who is living in our building is usually loud.

(11) (O-S): We met the young man who sold his new car.

(12) (PN-S): This is my friend who lives in another city.

(13) (EX-S): There is a cute baby who drinks a lot of milk.

(14) (S-O): The baby whom she fed is my nephew.

(15) (O-O): She called the manager whom we met at the coffee shop.

(16) (PN-O): This is my classmate that I invited to the party.

(17) (EX-O): There is a small cat that I found in the street.

The animacy of the head nouns and length of the clauses were controlled for in the sentences for both tests. To ensure that results were not due to a lack of knowledge of the English lexicon, participants were provided with a list of the words used in the tests in both the L1 and the L2.

The sentence combination test included 16 items, with two items for each of the eight RC types targeted in this study (see Table A1 in Appendix). The distribution of the test items was random. The reliability of the sentence combination test was checked using the Cronbach's alpha test,Footnote 4 which yielded a very good level of reliability for the test (0.83).

The translation test consisted of 16 test sentences, two test sentences for each type of RC targeted in the study (see Table A2 in Appendix). The test sentences were in Kurdish and the participants were asked to translate them into English. See (18) for an example of the translation task. The distribution of test items was random. The Cronbach's alpha value for this test was 0.88, which suggests high reliability of the measure.

(18)

Ew pîyaw- īlewê rawastawa bawk-î mine.

dem man-ez there is standing father-ez my

‘The man who is standing over there is my father.’

4.3 Procedure

The combination and translation tests were given under the same conditions of time and location. The use of the L1 in translation tests may have a priming effect, misleading the learners into using the native language. To avoid these priming effects, the combination test was given to the participants before the translation test. The time allocated was 40 minutes (20 minutes to complete each test).

Before doing the tests, participants were provided with instructions. For the combination test, participants were told to combine two separate sentences to form one sentence containing a relative clause. They were told that they needed to combine the sentences in such a way that the underlined words in sentence A would be identified by the information provided by sentence B, as in example (19). Participants were also told that they should always start with sentence A, and that they should not omit any information contained in the two sentences. In addition, a few examples were provided.

(19) A: We met the young man.

B: The young man sold his new car.

‘We met the young man who sold his new car.’

The combination test and the translation test were scored separately. In scoring each test, one point was assigned for each target-like use of the form, and zero points were assigned for non-target use. Since changing the order of the sentences A and B leads to the formation of sentences with different NPmat roles from the one expected, in each given test item, only the targeted RC was considered correct. Otherwise, the response was considered an error and the item was scored zero. Errors relevant to tense, number, or articles as well as minor grammatical errors and lexical mistakes that did not affect the structure and content of RCs were ignored in the scoring. Finally, the results obtained from the tests were analyzed quantitively: the total number of subject and object relatives formed correctly by the participants of the study were counted, and their percentages were calculated.

5. Results

One of the aims of this study was to investigate the predictions of the NPAH. Therefore, subject and object relatives in sentence combination and sentence translation tests were examined, and the RCs correctly formed by the participants of the study were counted. Table 1 shows the results pertaining to the total number of correctly-formed subject and object relatives in the combination test and the translation test. In each test, the total number of responses obtained for each RC type was 360. As the results show, the participants formed a larger number of subject relatives than object relatives. Therefore, subject relatives obtained higher scores than object relatives in the both tests. This result is compatible with the order of the first two types of RCs predicted by the NPAH. Furthermore, the high frequency of subject relatives in the data matches the first prediction of the NPAH, which claims that the subject position is the most accessible for relativization in all languages.

Table 1: Number and percentage of accurate responses in subject and object relatives in the sentence combination and the sentence translation tests.

The study also aimed to explore whether the attachment of subject and object relatives to NPs with different NPmat roles affects the rate of accuracy. According to the PDH and by considering the eight types of RCs in this study, it is expected that, for both subject and object relatives, the RCs occurring to the right of the matrix clause will show higher accuracy rates than centre-embedded RCs. Table 2 presents the mean accuracy scores for the two types of RCs (subject and object relatives), with the four different NPmat roles in the sentence combination test. The table also displays the number and the percentage of accurate responses out of the total number of possible responses, which is 90.

Table 2: Number and percentage of accurate responses, and mean accuracy scores on the sentence combination test by RC type and matrix position type

A closer look at the X-S patterns (subject relatives with different NPmat roles) shows that the mean accuracy scores on PN-S, EX-S, and O-S are higher than that on S-S. Furthermore, in X-O patterns (object relatives with different NPmat roles), the mean accuracy scores on PN-O, EX-O, and O-O are considerably higher than that on S-O. This raises the question of what distinguishes the three that behave alike from the odd one out. Syntactic functions cannot account for this, as the three with similar frequencies have different syntactic functions.

These differences could be explained by the position of RCs in the matrix clause. According to the results of the combination test, in both subject and object relatives, all the right attached RCs (PN-S, EX-S, O-S in subject relatives, and PN-O, EX-O, O-O in object relatives) had a higher accuracy rate than the centre-embedded ones (S-S in subject relatives, and S-O in object relatives). In other words, centre-embedded RCs obtained lower scores, as predicted by the PDH.

To test for the statistical significance, the Aligned Rank Transform (ART) ANOVA provided by the ARTool package (Kay et al. Reference Kay, Elkin, Higgins and Wobbrock2021) in the statistical analysis software R (R Core Team 2021) was used. Aligned Rank Transform (ART) ANOVA is a non-parametric approach to a factorial ANOVA that is useful when the data is not normally distributed, as was the case here, as demonstrated by the Shapiro-Wilk's normality test (Shapiro and Wilk Reference Shapiro and Wilk1965) and visual inspection of the histograms.

For the combination test, the ART ANOVA revealed a significant main effect for NPrel roles (F = 165.4742, df = 1, p < 0.000), a main effect for NPmat roles (F = 15.5729, df = 3, p < 0.000), and an interaction effect (F = 2.6505, df = 3, p = 0.04). To identify the source of the main effects, Tukey post hoc comparisons using art.con function were conducted. Post hoc comparisons showed statistically significant differences between right-attached and centre-embedded RCs in both subject and object relatives in the sentence combination test. The pairwise comparisons showed no significant difference between PN-S and EX-S, PN-S and O-S, and EX-S and O-S RCs. Furthermore, there was no significant difference between PN-O and EX-O, PN-O and O-O, and EX-O and O-O RCs. However, in subject relatives, there was a marginally significant difference between S-S and EX-S ( p = 0.08), and S-S and PN-S (p = 0.06), and a significant difference between S-S and O-S ( p = 0.00). Additionally, in object relatives, there was a significant difference between S-O and PN-O ( p = 0.00), S-O and EX-O ( p = 0.00), and S-O and O-O RCs ( p = 0.00). Thus, the accuracy order for subject and object RCs placed in different matrix positions could be summarized as follows: PN-S, EX-S, O-S > S-S, and PN-O, EX-O, O-O> S-O.

The results from the sentence translation test also support the first prediction of the NPAH, as subject relatives obtained a higher score (79.17%) than object relatives (46.94%). In terms of the position of RCs in the matrix clause, centre-embedded RCs (S-S in subject relatives, and S-O in object relatives) obtained lower scores than RCs on the right (O-S, PN-S, EX-S in subject relatives, and PN-O, EX-O, O-O in object relatives), as predicted by the PDH. The accuracy order displayed an identical pattern to that found for the combination test: O-S, PN-S, EX-S > S-S, and PN-O, EX-O, O-O> S-O. The results of the accuracy scores for each RC type are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3: Number and percentage of accurate responses, and mean accuracy scores on the sentence translation test by RC type and matrix position type

To statistically analyse the results, a non-parametric test of Aligned Rank Transform (ART) ANOVA was performed; Tukey post hoc comparisons using art.con function were conducted. The results showed a main effect for NPrel roles (F = 132.06598, df = 1, p < 0.000), and a main effect for NPmat roles (F = 9.80451, df = 3, p < 0.000), but no interaction (F = 0.81657, df = 3, p = 0.48). Post hoc comparisons revealed no significant difference between PN-S and EX-S, PN-S and O-S, EX-S and O-S, PN-O and EX-O, PN-O and O-O, and EX-O and O-O. However, in subject relatives, there was a significant difference between the mean ranks of S-S and PN-S ( p = 0.03), and S-S and O-S ( p = 0.00) RCs, and a marginally significant difference between S-S and EX-S ( p = 0.08). Additionally, in object relatives, there was a significant difference between S-O and PN-O ( p = 0.02), and S-O and EX-O (p = 0.03), and a marginally significant difference between S-O and O-O ( p = 0.06). Post hoc pairwise comparisons revealed a significant difference between right-attached and centre-embedded RCs in both subject and object relatives. Thus, the accuracy order obtained for different RC types can be summarized as follows: O-S, PN-S, EX-S > S-S, and PN-O, EX-O, O-O> S-O.

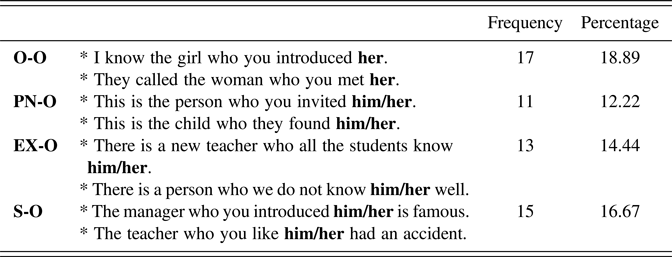

A closer analysis of the data revealed that the most frequent error type in both tests was related to the use of resumptive pronouns in object relatives. No errors related to the use of resumptive pronouns were found in subject relatives. Tables 4 and 5 display the frequency and percentage of errors related to the use of resumptive pronouns in the sentence combination and sentence translation tests, respectively. In all sentences, the asterisk (*) indicates that the sentence is ungrammatical. It should be noted that there were other erroneous RCs related to different error types; these are not reported here. In addition, there were test sentences that the participants avoided answering. Tables 4 and 5 display the percentages of errors out of the total number of possible responses (which was 90).

Table 4: Frequency and percentage of errors involving resumptive pronouns in the sentence combination test

Table 5: Frequency and percentage of errors involving resumptive pronouns in the sentence translation test

6. Discussion

The results from both tasks yielded a significant effect for RC type, supporting the first prediction of the NPAH, in that the mean accuracy in subject relatives was to a large extent higher than in object relatives. As discussed in section 1, in Standard English, both the linear and structural distance between the head noun and the gap are shorter in subject relatives, compared to object relatives. Thus, the Linear Distance Hypothesis and the Structural Distance Hypothesis can both explain why Kurdish Sorani-speaking learners of English find English subject relatives easier than object relatives. In addition, Prideaux and Baker (Reference Prideaux and Baker1986) argue that some types of cognitive processing strategies might largely affect the performance of learners in the formation of RCs. For instance, word order differences manifested in subject and object English relatives might be a possible reason for the better performance in the formation of subject relatives. There is a non-canonical argument order in object relatives (i.e., object before subject), which might create more difficulty for processing such sentences.

Word order in subject relatives in Kurdish Sorani (SOV) is different from English (SVO), while Kurdish Sorani has the same non-canonical word order (OSV) in object relatives as English. The present study demonstrates that, despite the inconsistency of word orders in subject relatives in L1 and L2, Kurdish Sorani-speaking learners of English find subject relatives easier than object relatives. This suggests that the inconsistency of word orders in RCs in L1 and L2 does not result in negative transfer. In addition, although the word order in object relatives in Kurdish Sorani is similar to that in English, Kurdish Sorani-speaking learners of English find object relatives more difficult than subject relatives. This indicates that the consistency of word orders in RCs in L1 and L2 does not ease the acquisition of RCs in L2.

While word order differences did not result in L1 transfer, there was evidence of crosslinguistic influence as far as resumptive pronouns are concerned. All the errors related to the use of resumptive pronouns occurred in object relatives (similar to what is found in Kurdish Sorani) and no instance of this type of error was found in subject relatives.

In addition to the above-mentioned findings, the inclusion of all the NPmat roles allowed the consideration of additional factors. The study provided evidence that the rate of accuracy in the formation of subject and object relatives does not significantly change by varying the NPmat roles; however, the rate of accuracy is significantly affected by the position of the RC in the matrix clause (centre-embedded or not). The results of both tasks showed that in each type of relatives (subject or object), RCs attached on the right obtained higher accuracy scores than centre-embedded RCs, yielding the following accuracy orders:

Subject relatives: PN-S, EX-S, O-S > S-S;

Object relatives: PN-O, EX-O, O-O > S-O

Thus, the predictions of the PDH were borne out by the results of both the translation and the combination tasks. According to the PDH, because of the limitation of human working memory, the interruption of the flow of a matrix clause by the insertion of a relative clause is likely to make the processing of centre-embedded RCs more difficult. The results suggest that the lower difficulty level of right-attached RCs compared to centre-embedded RCs leads to more successful acquisition and, in turn, better performance in the formation of RCs that are located at the edge of the matrix clause.

7. Conclusion

The present study investigated the performance of Kurdish Sorani-speaking learners of English in the formation of subject and object English RCs in which the NPmat role was either subject, object, predicate nominal, or predicative complement of an existential clause. The results supported the predictions of the NPAH and the PDH. The NPAH was supported, as it turned out that the subject relatives, with any NPmat roles, caused the fewest errors. Additionally, the PDH, which predicts ease of processing RC types on the basis of the position of the RC in the matrix sentence, was confirmed by the fact that in both subject and object relatives, all RCs located on the right had a higher accuracy rate than the centre-embedded RCs. In sum, the results were consistent with the results of previous studies which supported the predictions of the NPAH as well as the PDH.

The aggregate results and the patterns obtained suggest that the NPAH and the PDH should be seen as complementary. The NPAH is psychologically motivated, and categorizes RC types based on the syntactic functions of the NP relativized within the RC, whereas the PDH is motivated by memory-related processing and focuses on the processing interruption created by RCs in the centre of the matrix clause. Furthermore, the results indicate that in addition to the NPrel role and the position of RCs in the matrix clause, the properties of RCs in L1 affect the acquisition and formation of RCs by adults in L2 settings, as revealed by the use of resumptive pronouns in the L2. The present study was the first to be conducted on L2 acquisition of relative clauses by Kurdish Sorani native speakers. Further studies using other types of elicitation tasks and other positions on the NPAH can develop our understanding of the acquisition of relative clauses.

Appendix

Table A1: Sentence combination task

Table A2: Sentence translation task with transliteration and English translation