Public support is important for the legitimacy and viability of any political institution. This is especially so for courts given that judges lack formal mechanisms to enforce their own rulings and must rely on the other branches of government for their decisions to be enacted. This imperative can be challenging considering that courts, especially high courts, can make decisions that are unpopular with part or even a majority of the public. Therefore, the public’s support of judicial power and a court’s legitimacy more generally is essential to understand as a broader part of the way we conceive of the efficacy of democratic norms.

While court support in Canada does remain relatively high in comparison with other political institutions, public opinion data show that confidence in the courts has waned from the early 2000s to present day. A decline in public support is concerning in terms of its effect on the perceived legitimacy of Canada’s judicial branch. Just as concerning, it may speak to legitimacy challenges for Canada’s political institutions more generally. Research from the United States and Australia suggest that trust in government more generally structures the public’s views of the courts so that they rise and fall with evaluations of other branches of the government (Durr, Martin, and Wolbrecht Reference Durr, Martin and Wolbrecht2000; Haglin et al. Reference Haglin, Jordan, Merrill and Ura2020; Krebs, Nielsen, and Smyth Reference Krebs, Nielsen and Smyth2019; Sinozich Reference Sinozich2016). Understanding the sources that motivate this decline in public support for the judiciary is of great importance as western democracies grapple with widespread evidence of a loss of institutional trust (Dalton Reference Dalton, Zmerli and Van der Meer2017; Zmerli and Van der Meer Reference Zmerli and Van der Meer2017).

Moreover, Canada’s Supreme Court recently experienced a uniquely acrimonious period in terms of its relationship with the other branches of government (Crandall Reference Crandall, Marland, Giasson and Lawlor2018; Macfarlane Reference Macfarlane2018; Manfredi Reference Manfredi2016). This culminated in 2014, when Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper and his Minister of Justice rebuked the Chief Justice for allegedly trying to interfere with the appointment of another justice to the Court (Mathen and Plaxton Reference Mathen and Plaxton2020). This kind of public conflict between the members of the executive and judicial branches was unprecedented and prompts questions regarding how such events may have affected public support of Canadian courts, especially amongst supporters of the Conservative Party.

It seems plausible, then, that this recent decline in support for Canadian courts may be symptomatic of particular issues related to the courts and/or larger challenges to Canadian democracy, many of which may be bound up with broader perceptions of institutional trust and increased partisanship. This article explores these questions and proceeds as follows: we begin by canvassing the existing literature on public support for courts, with a particular focus on studies of the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC). We then investigate the fraught relationship between the Conservative government of Stephen Harper (2006–15) and the SCC in the latter part of Harper’s tenure as prime minister. Next, we analyze survey data from the Canadian Election Study (CES) from 2008 to 2019 to evaluate: (1) contemporary support for Canadian courts and its evolution over time; and (2) political values or attitudes that underscore court support. Our results point to several important findings. Consistent with comparative research, we find that court support in Canada is tied to education levels, perspectives towards equality, support for other government institutions, and general satisfaction with democracy. Importantly, whereas there was previously little evidence to support a claim that institutional support was contingent on partisanship, we find that partisanship has become a defining characteristic of court support in Canada. In particular, during the period of Conservative government analyzed here, Conservative supporters were significantly less likely to support the courts. While institutional trust is also found to be a strong predictor of court support, this suggests courts in Canada may now be more vulnerable to policy-based factors with strong partisan undercurrents. Public attitudes towards courts—particularly the SCC—may no longer be well shielded from the effects of changing political circumstances.

Literature on Public Support of Courts

Research on the factors affecting court support has been developed most extensively by scholars of the Supreme Court of the United States (see for example, Caldeira and Gibson Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992; Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003; Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2015; Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020). Bartels and Johnston (Reference Bartels and Johnston2020) separate this large body of US literature into two types: (1) those employing a process-based framework, and (2) those employing a policy-based framework.

For the process-based approach, the focus for understanding court support is on citizens’ perceptions of the way a court makes its decisions (diffuse support), as opposed to the outcomes of those decisions (specific support) (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020, 14). Within this approach, the theory of institutional legitimacy is arguably the dominant explanation for how courts are able to successfully navigate the challenges of maintaining public support. What does it mean for a political institution to have legitimacy? Generally speaking, legitimacy is treated as a normative concept concerning the right, both moral and legal, to make decisions (Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003, 354). For studies of court support, diffuse support is commonly used as a synonym for legitimacy. It is understood as a kind of institutional loyalty, capable of creating “a reservoir of favourable attitudes or good will that helps members to accept or tolerate outputs to which they are opposed or the effects of which they see as damaging to their wants” (Easton Reference Easton1965, 273). Because diffuse support is not contingent on the outputs of an institution (i.e., a court’s decision), a displeasing policy outcome should not undermine support of the institution, at least in the short term. This kind of diffuse support for the courts is contrasted with specific support, which concerns whether a person agrees with a particular court decision. Legitimacy theory posits that when specific support is low (i.e., people are dissatisfied with a court’s decisions) diffuse support should be able to cushion the impact of this policy dissatisfaction, thus maintaining the institutional legitimacy of the court. Developed most extensively by Gibson, Caldeira, and a number of collaborators (e.g., Caldeira and Gibson Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992; Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2005), this research suggests that even in the United States, where the ideological divisions between its Supreme Court’s judges are quite apparent, the most important predictor of diffuse support is general attitudes towards democratic values. Within the literature employing a process-based framework, a number of other factors have also been used to explain court support, from perceptions of the procedural fairness of judicial decision making (Farganis Reference Farganis2012; Tyler Reference Tyler1994; Reference Tyler2006; Ramirez Reference Ramirez2008), to the institutional loyalty fostered by the symbolism and unique procedural process of judicial decision making (Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2009; Gibson, Lodge, and Woodson Reference Gibson, Lodge and Woodson2014).

By contrast, the policy-based approach argues that citizens care most about the outcome of a court’s decision, making procedural aspects and core democratic values less important for understanding citizens’ support for a court’s power (for examples, see Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020; Reference Bartels and Johnston2013; Bartels and Kramon Reference Bartels and Kramon2020; Christenson and Glick Reference Christenson and Glick2015; Nicholson and Hansford Reference Nicholson and Hansford2014; Sen Reference Sen2017; Zilis Reference Zilis2015; Reference Zilis2018). These two frameworks offer different explanations in response to the question of what informs citizens’ support of a court’s power and its legitimacy, with those employing a policy-based approach encouraging us to understand citizens’ attitudes towards their courts in more explicitly political terms. Despite these different theoretical explanations for what informs citizens’ support of US courts, it is certainly not an either–or scenario. Rather, findings within these two literatures are often complementary. For example, in their study of court curbing of the US Supreme Court, which ultimately argues for the explanatory value of a policy-based approach, Bartels and Johnston (Reference Bartels and Johnston2020, 99–103) find that those with greater political engagement, higher levels of political trust, and more than a high school-level education are significantly less supportive of attacks of the court, all factors that are also consistent with a process-based explanatory framework.

Research on Canadian courts is far less extensive. Despite the well-acknowledged policy- and law-making roles of the SCC since the entrenchment of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, the trends and mechanics of popular support of the SCC, and Canadian courts more generally, remain comparatively underdeveloped. With a few notable exceptions (Fletcher and Howe Reference Fletcher and Howe2000; Goodyear-Grant, Matthews, and Hiebert Reference Goodyear-Grant, Matthews and Hiebert2013; Hausegger and Riddell Reference Hausegger and Riddell2004; Sniderman et al. Reference Sniderman, Fletcher, Russell and Telock1996), studies of the SCC have not focused on this topic at all. Other than surveys designed for the research by Sniderman et al. (Reference Sniderman, Fletcher, Russell and Telock1996), Fletcher and Howe (Reference Fletcher and Howe2000), and a small number administered by private polling firms like the Angus Reid Institute, data concerning public views of Canadian courts are essentially limited to the small battery of questions asked by the longitudinal CES. Figure 1 illustrates these data from 2008 to 2019, pointing to a generally high level of support for the courts over time, with some evidence of decline in the most recent year of the survey.

Figure 1. Level of confidence in Canadian courts according to the Canadian Election Study.

Hausegger and Riddell’s Reference Hausegger and Riddell2004 study provides the most developed analysis of the institutional legitimacy model for the Canadian case, though the data analyzed are now over twenty years old. Looking at two different time periods (1987 and 1997), they test whether support for Canadian courts was more a function of policy preferences (policy-based approach) or underlying political values (process-based approach). They find that in the latter time period (1997), support was more accurately determined by specific support for the Court’s decisions than by political values (diffuse support), suggesting that the more politically consequential role the SCC has played post-Charter had affected the public’s support for the institution.

Notably, political ideology was not a strong predictor of court support in these earlier studies. Hausegger and Riddell (Reference Hausegger and Riddell2004) found political ideology to be an insignificant predictor of diffuse support in their tested time periods (1987 and 1997), while Fletcher and Howe’s (Reference Fletcher and Howe2000) study, which analyzed survey data from 1999, found that only Reform Party members, those typically labeled the most conservative at the time, had significantly different attitudes from other respondents. However, as the political power of the SCC has continued to solidify and partisan attention to the work of the Court has increased in the years since, it seems possible that political ideology may play a stronger role today than it did twenty years ago. Indeed, research by Goodyear-Grant, Matthews, and Hiebert (Reference Goodyear-Grant, Matthews and Hiebert2013), which analyzed the 2004–2006 transitional period between the Liberal and Conservative federal governments, identified a change in preference for the government and courts among some Liberal and Conservative party supporters, suggesting partisan preferences were at play.

Following this logic, it seems possible that particular events with consequences for partisan control—such as the election of an individual with strong views about the courts—may also shift levels of court support. Thus, the recent tenure of Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper, which precipitated an unusually strained relationship between the federal government and the SCC frequently framed along ideological lines, provides a helpful case study to consider whether political ideology may now inform court support in Canada.

The Supreme Court of Canada and Conservative Government of Stephen Harper

Studies have consistently found relatively strong levels of public support for Canada’s Supreme Court compared with support for other Canadian political institutions and actors (Angus Reid Institute 2015; 2020; Fletcher and Howe Reference Fletcher and Howe2000; Hausegger and Riddell Reference Hausegger and Riddell2004), and the Canadian government and SCC have historically maintained the respectful relationship that is typical of consolidated democracies. While it is not unusual for a Canadian government to express disappointment when it loses a case at the SCC, its acceptance of the decision is nearly automatic. Moreover, since the entrenchment of the Charter in 1982, Canadian governments have overwhelmingly been supportive of this bill of rights and the corresponding growth of the SCC’s role in rights review. The notable exception to this generally cordial relationship came during the tenure of Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s Conservative government, which was in power from 2006 to 2015. Compared with the Progressive Conservative (PC) government of Brian Mulroney (1984–1992) and multiple Liberal governments (Jean Chrétien 1993–2003; Paul Martin 2003–2006; Justin Trudeau 2015–present) that have formed since the entrenchment of the Charter, the Conservative Party of Canada (CPC), which was created in 2003 following the merger of the PC and Canadian Alliance parties, has generally been more suspicious of possible policy overreach by the SCC and the policy effects of the Charter. Notably, these views were held by the party’s first leader, Stephen Harper. For example, in 2000 he noted, “Yes, I share many of the concerns of my colleagues and allies about biased ‘judicial activism’ and its extremes. I agree that serious flaws exist in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and that there is no meaningful review or accountability mechanisms for Supreme Court justices” (Makin Reference Makin2011).

While the Conservative Party’s scepticism regarding the work of the SCC was well known when it formed government in 2006, it was not until the last few years of its tenure that the relationship between the government and the SCC became publicly strained and departed from the expected norms of executive–judicial relations in Canada. In May 2014, this culminated in Harper and his Minister of Justice, Peter MacKay, publicly rebuking then Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin for allegedly trying to interfere with the appointment of Justice Marc Nadon to the SCC while the constitutional status of his appointment was being reviewed by the Court itself. The details of this reference case (Reference re Supreme Court Act, ss 5 and 6, 2014 SCC 21, [2014] 1 SCR 433), which addressed the constitutional status of the SCC and its consequences for Justice Nadon’s eligibility to serve as a Quebec judge are complex (for details see Mathen and Plaxton Reference Mathen and Plaxton2020). What is notable here is that these criticisms launched against the Chief Justice came after several high-profile government losses before the SCC, including the Nadon reference in March and the Senate reference (Reference re Senate Reform, 2014 SCC 32) in late April, which effectively blocked the Conservative government’s long-standing efforts to make Canada’s upper house elected. The public rebuke of the Chief Justice was so outside the norm of executive–judicial relations that eleven former presidents of the Canadian Bar Association expressed their concerns about the incident in a jointly written op-ed, explaining that the “Prime Minister’s statements may intimidate or harm the ability of the Supreme Court of Canada to render justice objectively and fairly” (CBA Presidents 2014). Thus, this public criticism of the Chief Justice occurred within a fairly clear political context, with members of the Conservative government being described as “incensed” that the SCC had “blocked Parliament’s ability to make laws” as freely as it might have wanted (Ivison Reference Ivison2014). This view of the SCC as a significant roadblock to the Conservative government’s policy agenda is also consistent with how the popular media portrayed the relationship at the time (Fine Reference Fine2014; Garson Reference Garson2014; Ling Reference Ling2014).

While the adversarial relationship between the Conservative government and the SCC was thus apparent and well publicized, the question of whether the SCC actually acted as a major roadblock to the Conservative government’s policy agenda is also worth addressing. In general, the SCC rarely overturns laws passed by the sitting government. In line with this empirical rule of thumb, a study by Manfredi (Reference Manfredi2016) found that the Harper government’s record before the SCC was not outside of the norm of previous governments, with only about one-quarter of the laws struck down by the Court having been passed by the Harper government. However, when issue salience is accounted for, a different picture of the Conservative government’s record at the Supreme Court emerges. Using the presence of a policy issue in the governing party’s election campaign platform as a proxy for issue salience, Macfarlane (Reference Macfarlane2018) finds that, in contrast to all other governments during the post-Charter era, the Conservative government is the only one to have specific platform promises declared unconstitutional by the SCC. Similarly, in his analysis of criminal law cases, Hennigar (Reference Hennigar2017, 1262) finds that of the eleven SCC cases in which criminal laws were invalidated, six were passed by the Harper government. Criminal justice was a well-known priority of the Conservative government (Hennigar Reference Hennigar2017; Kelly and Puddister Reference Kelly and Puddister2017) and this rate of invalidation (55%) is considerably higher than that found by Manfredi (25%).

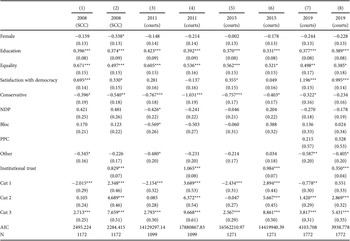

How were these high-profile court losses received by the public? Data measuring public support of specific SCC decisions are scarce in Canada; however, a 2015 survey by Angus Reid suggests that the Conservatives’ comparatively poor track record at the SCC was also reflected in its supporters’ views on specific decisions. Figure 2 illustrates support for SCC decisions on politically salient matters heard in the first half of the 2010s. With respect to the Bedford case (Canada (Attorney General) v Bedford, 2013 SCC 72, [2013] 3 SCR 1101), where the Court struck down prostitution laws, a majority of Canadians supported the decision, with the highest support coming from Liberal voters at 70% (all t-tests between Liberals and each of the other major four parties were significant at the .05 level) and the lowest from Conservatives at 50% (also significant). Similar patterns hold for the Tsilhqot’in (Tsilhqot’in Nation v British Columbia, 2014 SCC 44, [2014] 2 SCR 256) decision regarding Aboriginal title. In the Carter case (Carter v Canada (Attorney General), 2015 SCC 5, [2015] 1 SCR 331) that removed prohibitions around medically assisted dying, Liberal and Bloc Québécois supporters were equally likely to support the Court’s position (62% and 64%, respectively), with Conservative supporters far less enthusiastic about the decision at 48%. Few Canadians overall (37%) thought highly of the Court’s decision to strike down mandatory minimums on firearm possession (R v Nur, 2015 SCC 15, [2015] 1 SCR 773), but the partisan patterns that appear in other indicators hold true even for this decision. While not all of these decisions may be considered losses for the Conservative government, the lower level of support for these decisions by Conservative supporters appears in line with the general assessment that this was a difficult period for the Conservative government at the SCC.

Figure 2. Partisan support for decisions made by the Supreme Court of Canada on politically salient matters. BQ = Bloc Québécois; CPC = Conservative Party of Canada; LPC = Liberal Party of Canada; NDP = New Democratic Party.

Public survey data also suggest that partisanship may have played a more important role in SCC support during the Conservative government’s time in power. Overall, public support for the Supreme Court appears to have fluctuated over the past decade, from a low of 31% support in 2012 to a high of 57% in 2016, dropping again to 48% by 2020 (Angus Reid 2020). During this period, there also appear to be notable differences along party lines. Angus Reid data from 2015 show that those who voted Conservative in the 2011 federal election had weaker (and significantly so) levels of support for the SCC (56%), than Liberal (79%), NDP (63%), or Bloc supporters (73%) (t-test differences significant at the .05 level). This weaker Conservative support is also observed in a 2020 Angus Reid survey, with 68% of respondents who voted Conservative in the 2019 federal election expressing a “complete lack” or “not a lot” of confidence in the SCC, in comparison with only 20% of Liberal respondents. Altogether, these data suggest notable divisions in SCC support along partisan lines, with Conservative Party identifiers being the most likely to express a lack of support for the SCC.Footnote 1

Thus, by measures of both public appearance and empirical record, the Harper government seemed to have a uniquely fractious relationship with the SCC. Descriptive public survey data also suggest that this period may have witnessed strengthened partisanship at play in estimates of support for the Court, with Conservatives being less likely to support the Court and its decisions on politically salient cases. Given the theoretical and empirical observations above, we hypothesize the following:

H1 (Institutional Legitimacy): Support for the courts will be positively correlated with other measures of institutional legitimacy.

H2 (Partisanship): Conservative partisans are more likely to exhibit lower levels of support for the courts than non-conservative partisans.

H3 (Partisanship x time): The presence of a Conservative prime minister should strengthen the effect in H2, after which conservative partisans are more likely to decrease their support for the courts than non-conservative partisans.

H4 (Partisanship x time x trust): If support for the courts is positively correlated with other measures of institutional legitimacy (H1), these changes in support should be mediated by strong perceptions of institutional trust.

Data and Methods

Our goal in this paper is to disentangle some of the underlying mechanisms of court support in Canada to determine how partisanship, institutional trust or a combination can add insight to our understanding. Using the nationally representative Canada Election Study from 2008, 2011, 2015, and 2019, we track court support during a twelve-year period. Our dependent variables of interest are (1) a four-point indicator asking respondents how much confidence they have in the courts (ranging from “None” to “A Great Deal”), and (2) a binary indicator asking, “If a law conflicts with the Charter of Rights, who should have the final say?”, where the respondent could answer “the courts” or “the government.” Ideally, the CES would include separate measures for support of “the courts” and the “Supreme Court” but instead asks specifically about the Supreme Court in 2008 and courts generally from 2011 onward. Therefore, we present our findings with the important caveat that we are gauging support for courts overall and extrapolating these findings to make inferences about the Supreme Court. We believe this is a fair assumption given the average Canadian’s lack of exposure to the court system and, therefore, the unlikelihood that they would distinguish between levels of court; however, we acknowledge this limitation.

Without recounting their theoretical reasoning for the inclusion of a series of indicators, we observe that Haussegar and Riddell’s study from 2004 incorporated socio-demographics, measures of political efficacy, and attitudes towards salient policy issues at two discrete time points, 1987 and 1997. While age did reach conventional levels of significance in both years, few other variables consistently performed well in explaining court support. Given this lack of clear correlates and the length of time since the study, we take as our starting point the literatures on institutional trust and comparative court support (e.g., Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020; Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998; Krebs, Nielsen, and Smyth Reference Krebs, Nielsen and Smyth2019), and control for relevant socio-demographics (gender, educationFootnote 2), attitudes towards policy issues that the courts routinely adjudicate (equality), level of satisfaction with democracy, partisanship, and levels of general institutional trust (see Table I for descriptive statistics). Gender is coded as binary (identifying as female or not) and education into three categories (less than high school; some college/university; a degree or higher). Perception towards equality (binary) is measured as agreement with the statement “We have gone too far in pushing equal rights in this country.” Level of satisfaction with democracy is a binary measure of whether an individual reports that they are satisfied with the way democracy works in Canada. Partisanship is a set of binary controls for party identification with Liberal acting as the baseline for comparison. Finally, institutional trust is a mean-centred summative scale that sums positive responses to indicators measuring trust in the federal government, provincial government, civil service, police, and the media (alpha=.69).

Table I Descriptive Statistics of Dependent and Independent Variables

Median (η) provided for ordinal variables; % provided for binary variables. Equality refers to disagreement with the statement “We have gone too far in pushing equal rights in this country.” Level of satisfaction with democracy is a binary measure of whether an individual is satisfied with the way democracy works in Canada.

*Note: The answer set for the Equality variable includes “Neither agree nor disagree,” which was not included in the 2008–2015 answer set. Therefore, reporting in 2019 represents those who stated “somewhat agree” or “strongly agree” as a proportion of those who responded, less those who selected “Neither agree nor disagree” to ensure comparability with other years.

Support for and Trust in Canadian Courts

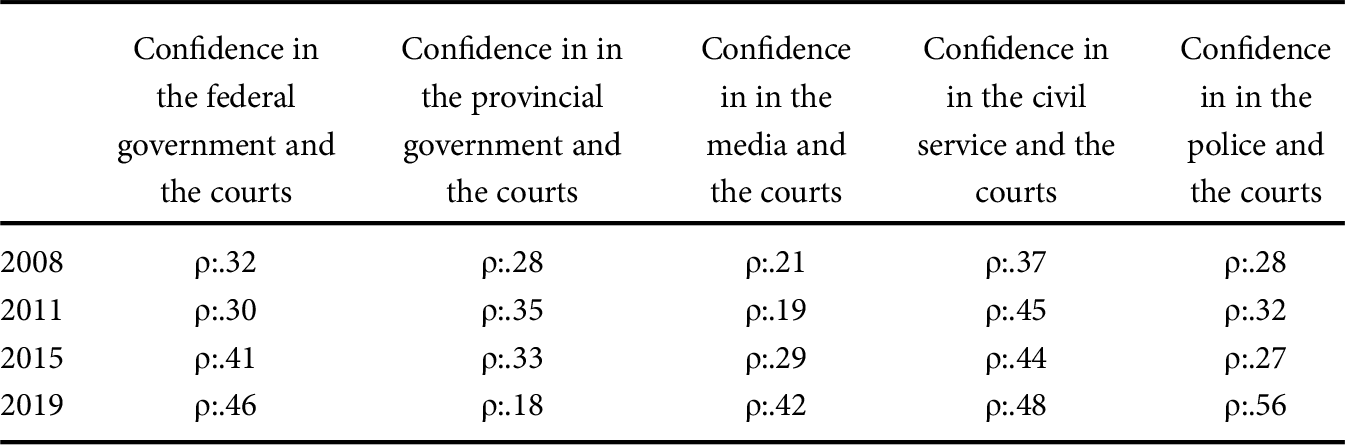

Similar to the findings in comparative research on courts, it may be the case that support for the courts is partially dependent on perceptions of the relationship between the court and government or other political institutions (H1). Support for the courts may be dependent on an individual’s support for the party in power federally, either owing to the knowledge that this party is making judicial appointments or that the court could function as a check on that party. Table II presents correlational data from the CES (2008 to 2019) that show confidence in the courts is moderately to strongly (and significantly) correlated with confidence in the federal government (ranging from ρ:.30 in 2011 to ρ:.46 in 2019, all significant at the .001 level), though it is less reliably correlated with confidence in a respondent’s provincial government (ranging from ρ:.18 in 2019 to ρ:.35 in 2011, significant at the .001 level). Notably, court support is most strongly correlated with confidence in the civil service (ranging from ρ:37 in 2008 to ρ:48 in 2019, significant at the .001 level). This connection may not be surprising given that these institutions are more likely to be perceived as non-partisan (even if partisan appointments play an important role for both institutions). Confidence in the police is also moderate to strong in this time period, ranging from .27 in 2015 to a high of .56 in 2019 (significant at the .001 level). Finally, court support is positively correlated with support for the media, though the strength of the correlation varies (ranging from ρ:.19 in 2011 to ρ:.42 in 2019, significant at the .001 level), suggesting that trust in the courts may be emblematic of a broader trust in political institutions. On the other hand, the comparatively low correlations from 2008 to 2015 may also be reflective of concerns about the politicized nature of media (though such an explanation would not account for the relatively high correlation in 2019 when the media had been under increased scrutiny owing to claims of misinformation circulating about election-related issues). Taken together, these data suggest a strong overall level of institutional trust in Canada and strong linkages between confidence levels in institutions. However, the higher correlations between court support and support for the federal government when compared with the correlations between court and provincial government support suggest that court support may be closely linked with the perception that a federal government will secure court appointments reflective of their ideological leanings, or, quite simply, that when approval of the federal government is high, this has a positive knock-on effect for other federal institutions that are perceived to be in line with the government (whether or not they are).

Table II Canada Election Study (2008–2019): Institutional Trust Correlations*

Canada Election Study 2008–2019 (Mail back survey; Online survey).

Note: 2008 survey asks about Supreme Court of Canada; 2011–2019 ask about “courts.”

* All correlations are significant at the p=0.001 level.

Importantly, we see preliminary evidence that these data are suggestive of underlying partisan effects. When looking at plausible reasons for the low correlation between the courts and provincial governments in 2019, we find that the level of correlation remains the same for all regions except for the West (whose population tends toward conservative partisanship). When looking at this relationship for respondents from the West—who have commonly expressed a dissatisfaction with their representation in key political institutions, particularly those that have appointment systems that tend to underrepresent their region—the correlation between confidence in the courts and provincial government drops to .06 and becomes insignificant. We may interpret this lack of a relationship as suggestive of a connection between partisanship and court support, though further analysis is warranted.

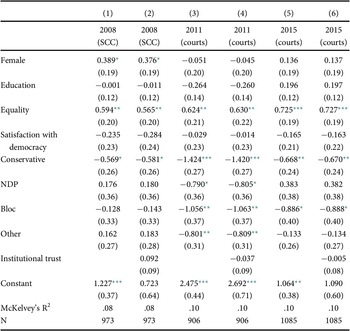

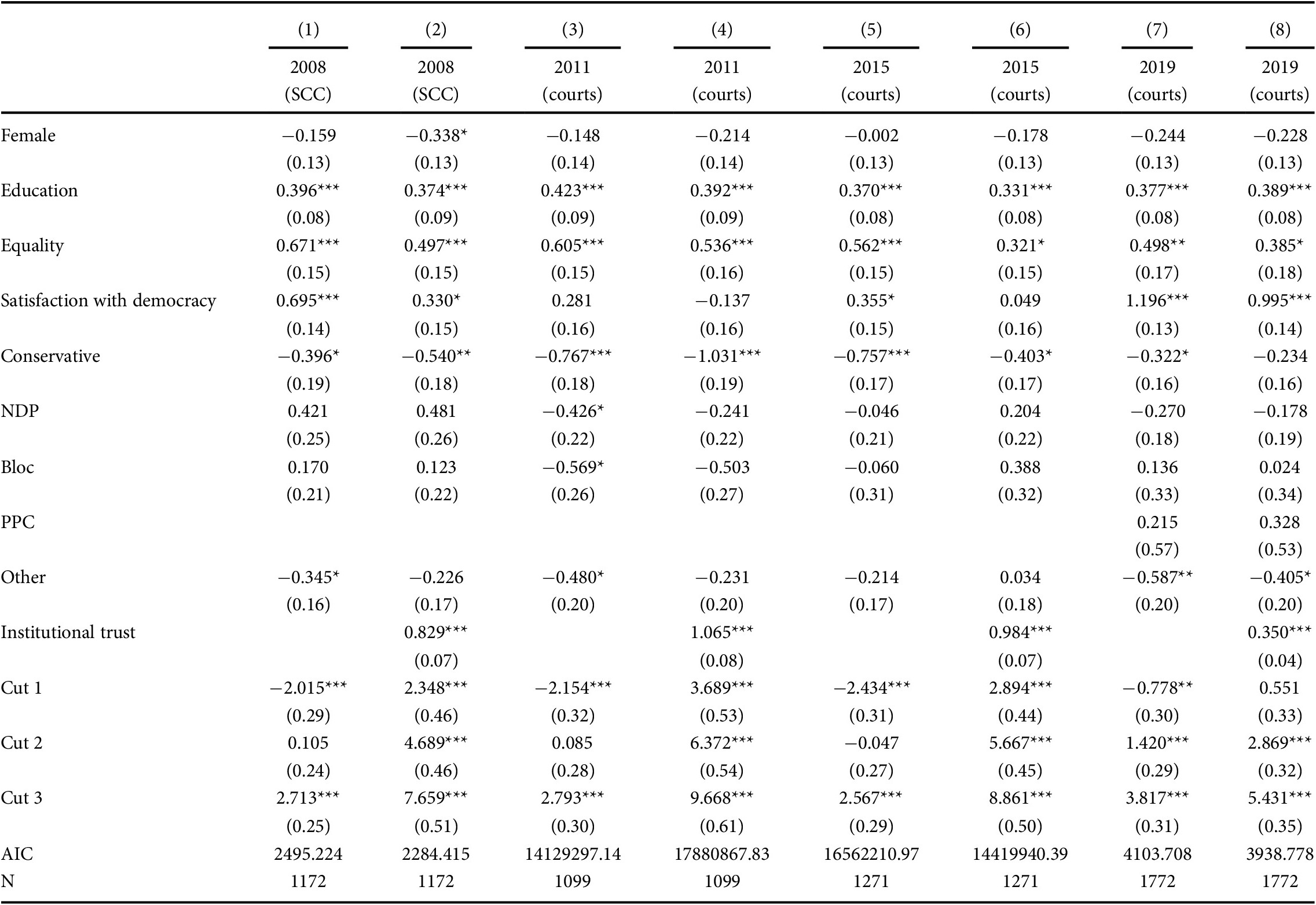

Turning to our second, third, and fourth hypotheses, Table III presents a series of ordered logit models (by year) for our first dependent variable of interest—court support. All models are weighted using the CES’s population weights. Each year’s model is run in a stepwise fashion: first the expected correlates of court support are provided, including partisanship, which we suspect has a direct relationship with court support (H2), though we think this is also related to the government in power (H3). In the second set of models, we add in our institutional trust scale to determine whether perceptions of institutional legitimacy have a dampening effect on any trends detected in the partisanship model (H4).

Table III Confidence in the Courts.

Dependent Variable: How much confidence do you have in the SCC (2008) / courts (2011–2019)? Ordered Logit Model.

NDP = New Democratic Party; PPC = People’s Party of Canada; SCC = Supreme Court of Canada.

First, our data illustrate that support for the courts is stronger (and statistically significant) among the more highly educated, which is consistent with comparative findings that those who know something about the courts are more likely to be favourably oriented towards them (e.g., Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998). Support is also stronger (and statistically significant) among those who have more progressive views on equality issues, which Hausegger and Riddell (Reference Hausegger and Riddell2004, 39–41) found some support for in their earlier study of the SCC. Satisfaction with democracy also has a positive and significant relationship with court support in all years except 2011; it also had a weaker relationship in 2015. These findings are consistent with process-based theories of court support, which emphasize political engagement and core democratic values as important predictors (see Caldeira and Gibson Reference Caldeira and Gibson1992; Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2009; Gibson and Nelson Reference Gibson and Nelson2015).

As it relates to our main hypotheses, the model presents evidence of partisan effects, confirming hypothesis 2. In each base model (models 1, 3, 5, and 7) that includes partisanship (but not institutional trust), Conservative partisan self-identification displays a negative and significant relationship with court support (compared with the baseline category, Liberal). There is scant evidence of other partisan effects, except in 2011, when both NDP and Bloc Québécois partisans are also significantly associated with negative support for the courts. One possible explanation for this multi-party effect identified in 2011 is the Conservative Party’s minority government status at the time. Its reliance on the support of the opposition parties to remain in power gave the NDP and Bloc Québécois, two parties that have never formed a government, more influence over the parliamentary agenda during this period. This type of politically pragmatic explanation would mean that NDP and Bloc Québécois partisans are less likely to support the courts at a time when their parties hold more influence over government, as was the case prior to the outcome of the 2011 election.

When institutional trust is added into the models (models 2, 4, 6, and 8), two notable findings emerge. First, institutional trust is positive and significant in all years. In other words, for each one-unit increase on the trust scale, the odds of high court support are, on average, 2.31 times greater than the lower support categories (when all of the other variables in the model are held constant).Footnote 3 The second finding relates to the partisanship effect. When trust is included in the models, the negative and significant effect for Conservative partisans remains in place for 2008, 2011 and 2015, but disappears in 2019, suggesting support for hypotheses 3 and 4 that are respectively concerned with the effects of timing and trust. This suggests that Conservative partisanship appears to affect court support in the Harper era, but dissolves once the party is no longer in power.

Figure 3 further fleshes out the relationship between partisanship and institutional trust. The four panels, representing the four election cycles covered in this analysis, all reflect the same trend. As the value of institutional trust (on the ten-point trust scale) increases, the change in the probability of court support decreases from 0.4 in 2008 to a probability of nearly 0 for each group of partisan self-identifiers. The relationship becomes even more pronounced in 2011, where an increase in the value of institutional trust results in a probability change from 0.76 to nearly 0. Similar trends are evident in 2015 and 2019. All four panels follow similar patterns with results being more pronounced for Conservative partisans than their more centrist or left-of-centre partisans. In practice, these results suggest that confidence levels in courts are more likely to move amongst Conservative partisans when general perceptions of institutional trust are low—more so than for Liberal, NDP, or Bloc partisans. Notably, however, the slope for Conservative respondents in 2019 is much more gradual than the years that precede it. While the direction of the relationship remains the same, with Conservative partisans being more likely than their counterparts to show a relationship between confidence in the courts and perceptions of institutional trust, after Harper leaves office, this relationship becomes far less pronounced—only a quarter of what it was in 2011.

Figure 3. Predicted probabilities measuring relationship between perceptions of institutional trust and partisanship. BQ = Bloc Québécois; CPC = Conservative Party of Canada; LPC = Liberal Party of Canada; NDP = New Democratic Party.

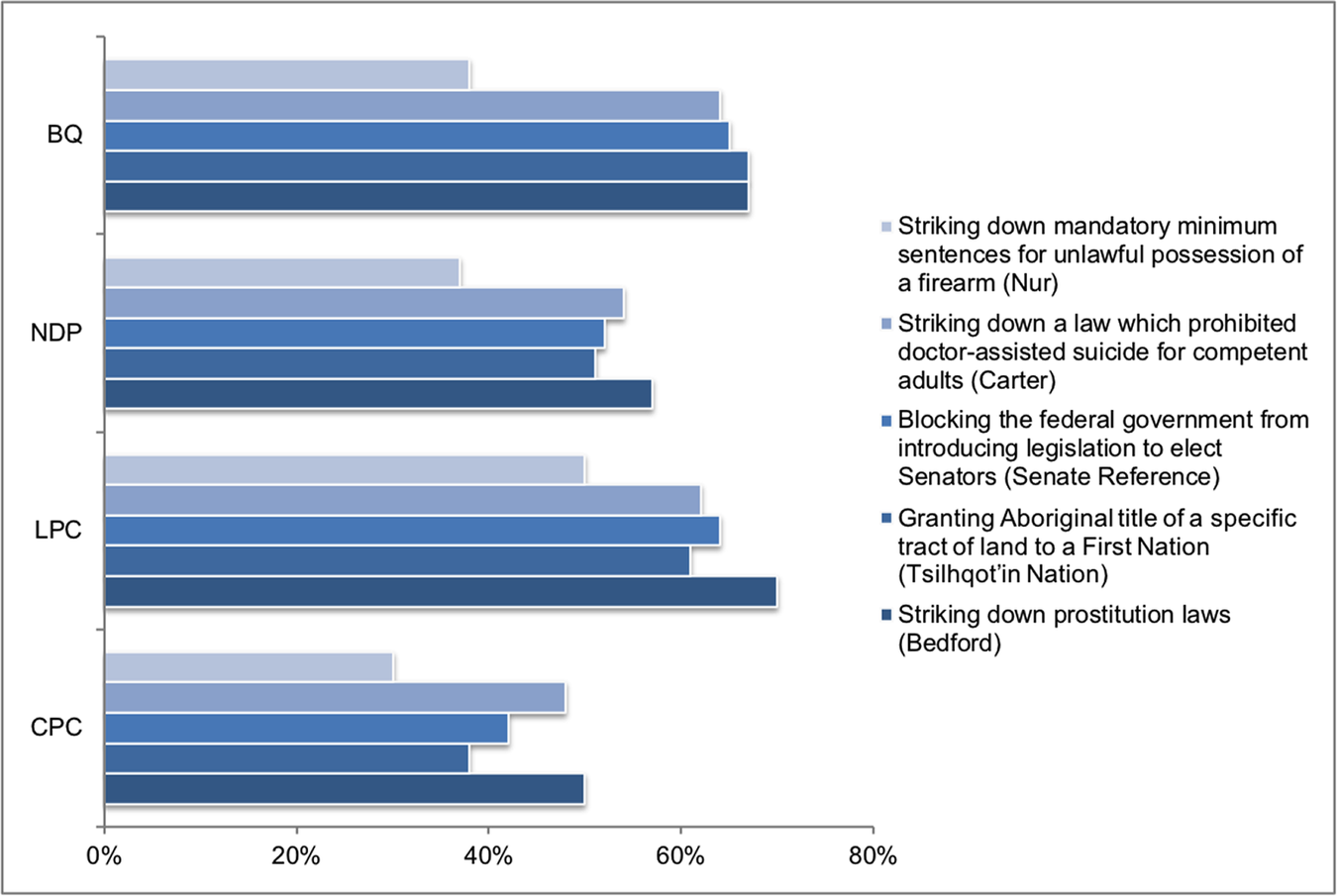

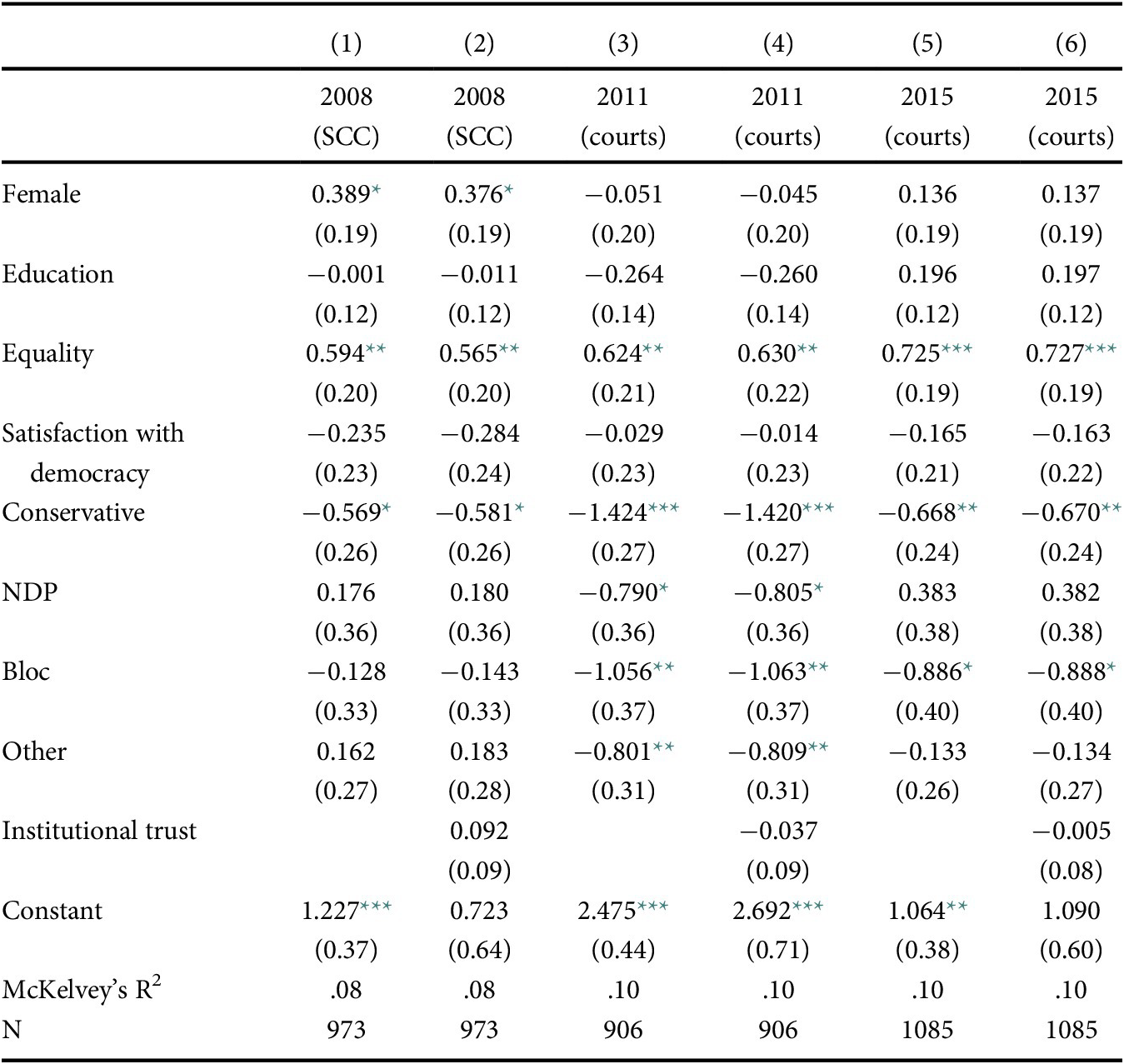

As a supplementary test and partial robustness check, the CES allows us to explore diffuse support using an indicator that asks who—the courts or the legislature—should have the final say on Charter-related policy matters. This dichotomous dependent variable has also been used by other studies of Canadian court support (Fletcher and Howe Reference Fletcher and Howe2000; Goodyear-Grant, Matthews, and Hiebert Reference Goodyear-Grant, Matthews and Hiebert2013; Hausegger and Riddell Reference Hausegger and Riddell2004). Here we see a similar trend on partisanship to our generalized model with an important caveat. In this model, we take support for the courts having the final say as our category of interest. Table IV provides evidence that perspectives towards equality matter in being pro-court. This is consistent with views that it is the courts’ role as the quintessential anti-majoritarian institution to protect rights from government overreach (see Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2009). Interestingly, the significant effects for education and satisfaction with democracy disappear, suggesting that the lines of differentiation on this matter are more likely to be related to fundamental perspectives on judicial or parliamentary supremacy, which are rooted in long-standing debates around majoritarian rule and constitutional dialogue (Hiebert Reference Hiebert, Goodyear-Grant and Hanniman2019; Hogg, Thornton, and Wright Reference Hogg, Thornton and Wright2007; Manfredi and Kelly Reference Manfredi and Kelly1999). While these debates do not overlay easily on a simple left–right political spectrum, Conservatives in Canada have traditionally favoured a stronger role for the legislative branch in the articulation of rights (Macfarlane Reference Macfarlane2018). It is therefore not surprising that Conservative partisanship matters in every iteration of the model. The coefficients are negative (pro-government) and significant in each year. Moreover, they remain so even when institutional trust is introduced into the model. To strengthen this point, we see that other forms of partisanship, particularly support for the Bloc Québécois, matter here as well. This is congruent with expectations since Bloc supporters are likely to favour a Quebec-centred agenda and support the Quebec government overriding the courts on Charter-related matters, an action seen most recently with the government’s use of the Charter’s notwithstanding clause for Bill 21, which forbids the wearing of religious symbols such as turbans, kippas, and hijabs for provincial employees. That institutional trust does not matter here is not particularly surprising. Unlike the general indicator of court support above, this measure positions the courts against their natural check, elected officials. Strong levels of institutional trust in this case would not reflect an exclusively pro-court position; it could equally reflect support for elected members of Parliament or provincial legislatures, and therefore could not reasonably show up as a significant indicator of this particular measure of support. On the other hand, the preference for legislative supremacy articulated by conservative parties in Canada means that we would expect a consistent pro-government position vis-à-vis the courts, regardless of how conservative partisans felt about general levels of confidence in government.

Table IV Public Support for the Courts

Dependent Variable: Who should have the final say if a law conflicts with the Charter (the government or courts)? [Question not asked in 2019]. SCC = Supreme Court of Canada.

* p<.05

** p<0.01

*** p<.001

Numbers in parentheses are standard errors.

Altogether, these findings give us important insights about both partisanship and trust as they relate to court support. As anticipated, partisanship has become a significant factor for explaining court support in Canada. This is important if we consider its small role in the Canadian literature to date. The resiliency of the institutional trust finding is also relevant to the Canadian literature on court support. Trust in the courts is not an isolated sentiment. The results in Tables II and III suggest that trust in the courts and trust in other government institutions are interdependent. Such a finding, particularly when taken in tandem with the aforementioned positive effect of satisfaction with democracy, suggests that overarching perceptions of the integrity of institutional forces and the way in which the apparatus of the state functions have stronger effects. Finally, taking these two measures together, this analysis shows the relevance of both variables, encouraging researchers to think past siloed arguments that would have citizens’ attitudes towards Canadian courts informed by either partisan or process-based factors alone. The mediation of the partisanship finding in 2019 (supporting hypothesis 3) suggests that while partisan sentiments may be stirred up by particular leaders who can introduce or expand upon discourses that may push back against a particularised form of institutional legitimacy, these may only be as strong as the political personalities that advance them. In their absence, perceptions of institutional trust appear to have stronger predictive power, a finding consistent with a process-based approach.

Discussion and Conclusion

Public support is a critical component of a court’s institutional legitimacy. This article has updated the data on public support of Canadian courts, paying particular attention to the relationship between (1) court support and political institutions more generally and (2) partisanship. Consistent with comparative research, we find that court support in Canada is tied to education levels, perspectives towards equality, support for other government institutions, and general satisfaction with democracy. This makes intuitive sense. If citizens view the judicial branch as part of a larger democratic system, then it seems reasonable to expect that citizens satisfied with Canadian democracy will also be supportive of Canadian courts. That said, this correlation may be concerning if larger trends in democratic dissatisfaction (Leduc and Pammett Reference Leduc, Pammett, Gidengil and Bastedo2014; Lenard and Simeon Reference Lenard and Simeon2012; Dalton Reference Dalton, Zmerli and Van der Meer2017) lead to a knock-on effect on court support.

We also find evidence of a partisan effect during the tenure of the Conservative government of Stephen Harper, with Conservative supporters being less likely to support the courts. This type of partisan division is especially notable given that it stands apart from earlier research on public support of Canadian courts and suggests that the perceived ideological neutrality of the courts, particularly the SCC given its high political salience during this period, may have decreased during the Harper era. The lessening of this partisan effect after the Conservative Party left office in 2015 suggests that it may not have lasting effects, though a decrease in overall court support identified in the 2019 CES data suggests that courts may nonetheless be facing an emerging legitimacy deficit. Certainly, further study will be warranted as new data become available in the next Canadian election cycle.

While this prompts many questions, it also makes clear why more public survey data focussed on Canadian courts are needed. In particular, we are unable to address what effects support for specific court decisions may have on diffuse support for courts in Canada. The 2015 Angus Reid survey, which probed respondents’ views on a series of SCC decisions, shows that Conservative supporters were less likely to support these decisions at a time when Conservative supporters were also less likely to support the courts in comparison with their partisan counterparts. Research on US courts employing a policy-based framework has identified a significant relationship between support of a court’s decision and general support for the court (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020; Christenson and Glick Reference Christenson and Glick2015; Reference Christenson and Glick2019). Future research on Canadian courts would be well served by investigating this relationship.

What are the possible political consequences of these findings? This paper confirms that the fractious relationship between the Harper Conservatives and the SCC did affect court support, at least in the short term. This was unlikely to go unnoticed by the SCC (McLachlin Reference McLachlin2019). Research in the United States has found a relationship between court support and decision-making (Clark Reference Clark2010; Epstein, Knight, and Martin Reference Epstein, Knight, Martin, Miller and Barnes2004), and it is known that Canadian justices are aware of the political pressure that sometimes surrounds their work (Greene et al. Reference Greene, McCormick, Szablowski, Thomas and Baar1998; Macfarlane Reference Macfarlane2013). Future research may want to investigate the relationship between public and elite court support and its effects on the decision-making of the SCC and other Canadian courts. These findings also have implications for judicial independence in Canada. Public support functions as a kind of shield for judicial independence. Policy-makers in a position to attack the court will be less likely to do so if they believe they will be reprimanded by the public (i.e., the idea that an attack carries a political cost). With this in mind, we can better understand why, in 2014, Prime Minister Harper may have opted to publicly criticize Chief Justice McLachlin. Those who supported the Conservative Party had a more negative attitude towards the SCC than others. For Harper, there was unlikely to be significant costs for attacking the SCC either to his base or more publicly in the media. Indeed, there may have been something to gain. If support for Canadian courts is following a downward trend, it may be the case that governing and opposition parties alike will be more willing to attack the SCC, which is bound to have reverberating effects for levels of trust in Canadian political institutions.