Introduction

Between 2002 and 2017, Canadian lawmakers sought to redress the pervasive levels of discrimination, harassment, and violence experienced by transgender and/or non-binary people by adding the terms “gender identity” and/or “gender expression” to federal, provincial, and territorial human rights instruments.Footnote 1 This paper tracks the complex, iterative ways in which anti-discrimination protections are brought to life outside courts and tribunals. As Michael Lipsky reminds us, policy is “not best understood as made in legislatures or top-floor suites of high-ranking administrators, because in important ways it is actually made in the crowded offices and daily encounters of street-level workers.”Footnote 2 Using Ontario’s publicly-funded English language secular school boards as a case study, we examine how the introduction of explicit human rights protections on the basis of “gender identity” and “gender expression” in 2012Footnote 3 worked to produce a series of responses across the education sector.Footnote 4

Given that “gender identity” and “gender expression” remain legally undefined terms in the Ontario Human Rights Code,Footnote 5 and only provisionally defined by Ontario Human Rights Commission policy,Footnote 6 we argue that school boards constitute important actors engaged in constructing the meanings of these terms in policy and practice. In decentering courts and tribunals in our analysis, we aim to uncover the everyday practices of parallel norm-making taking place in the education context. We also endeavour to build on the growing body of trans legal studies scholarship, which has tended to study reported court and tribunal decisions when assessing the efficacy of legislative reforms. These everyday practices in schools shape how we collectively understand the meaning of “gender identity” and “gender expression.” By carefully tracking these post-legislative developments, which rarely make their way into reported decisions, we suggest that human rights law reforms might open up space for the emergence of norms that allow people to do gender in a variety of ways.

The paper proceeds in four parts. Part I surveys the burgeoning body of trans legal studies scholarship, examining the introduction of formal human rights protections on the basis of “gender identity” and “gender expression” as sites of optimism and criticism. Part II tracks the making of “gender identity” and “gender expression” in human rights commissions, tribunal decisions, and legislative debates. Part III uses Ontario’s publicly-funded secular English-language school boards as a case study to examine how “gender identity” and “gender expression” protections are being brought to life outside courts and tribunals. Ultimately, the paper aims to provide an account of the variegated ways in which “gender identity” and “gender expression” norms are emerging in the education context in ways that shape our collective understandings of the terms themselves.

I. Human Rights Law: Modulating Between Optimism and Criticism

Over the past three decades, transgender and/or non-binary communities have harnessed human rights law in an effort to combat pervasive levels of discrimination, harassment, and violence in a variety of public and private contexts.Footnote 7 While claimants had, since at least 1982,Footnote 8 successfully argued that they were protected by existing human rights grounds including “sex”Footnote 9 and “disability,” Canadian lawmakers initiated the process of adding the terms “gender identity” and, later, “gender expression,” beginning in 2002.Footnote 10 As they amended human rights instruments across the country, lawmakers tended to make optimistic statements about the prospect of explicitly enshrining “gender identity” and “gender expression” in law. For example, during the second reading of Toby’s Act,Footnote 11 the law that added “gender identity” and “gender expression” as protected grounds in the Ontario Human Rights Code, Member of Provincial Parliament Cheri Di Novo proclaimed: “We need to save lives here. We need to include a group that has been excluded for a long, long time in the Ontario Human Rights Code.”Footnote 12 As of 2017, every jurisdiction in Canada—federal, provincial, and territorial—had introduced legislation amending their human rights codes to include “gender identity.” Most jurisdictions had also added “gender expression” as a protected ground of discrimination. However, none of the laws have expressly defined these terms.Footnote 13

This suite of legislative reforms explicitly added “gender identity” and “gender expression” to the corpus of Canadian anti-discrimination law. The paradigmatic anti-discrimination formula in Canada is to identify groups subject to discrimination, locate and define their characteristics, and frame those characteristics as prohibited grounds (e.g. “gender identity” and “gender expression”) that apply in contexts such as employment and service delivery.Footnote 14 In Canada, the principle of anti-discrimination finds expression in a variety of legal instruments, including the equality rights provision of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guaranteeing equal protection and benefit of the law “without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability,”Footnote 15 along with federal, provincial, and territorial human rights codes. The Ontario Human Rights Code,Footnote 16 for example, describes its underlying purpose as being to “recognize the dignity and worth of every person and to provide for equal rights and opportunities without discrimination that is contrary to law, and having as its aim the creation of a climate of understanding and mutual respect for the dignity and worth of each person so that each person feels a part of the community and able to contribute fully to the development and well-being of the community and the Province.”Footnote 17 In an effort to achieve this goal, the Ontario Human Rights Code prohibits discrimination and harassment on the basis of a series of grounds. Since its inception in 1961, the Ontario Human Rights Code has been amended over time to add new grounds, including “sex” in 1972,Footnote 18 “sexual orientation” in 1986,Footnote 19 and “gender identity” and “gender expression” in 2012.Footnote 20

In response to this dynamic of adding explicit anti-discrimination protections on the basis of “gender identity” and “gender expression,” a dynamic being mirrored across the Anglo-American world,Footnote 21 a burgeoning body of trans legal scholarship has posed normative questions about whether this development is “good” or “bad.” This scholarship has extended well-established debates in the field of human rights, which has long viewed legal recognition as a site of critique.Footnote 22 Some trans legal studies scholars have expressed optimism about the utility of using human rights frameworks. Others have criticized the push for explicit anti-discrimination protections, arguing that legal reforms are largely symbolic gestures that are unlikely to improve the material conditions of transgender and/or non-binary people, particularly for those located at multiple axes of oppression. In a number of instances, however, writers have modulated between optimism and criticism, underscoring the importance of recognizing the limitations of human rights law protections, without abandoning such approaches altogether. What follows below is a brief sketch of this emerging body of scholarship. Ultimately, our study aims to make a contribution to this literature by empirically demonstrating the ways in which human rights law reforms might open up space for the emergence of norms that allow people to do gender in a variety of ways.

1. The Promise of Human Rights Recognition

Human rights law aims to achieve symbolic, educative, and instrumental purposes. Symbolically, human rights protections seek to mark the formal social and legal recognition of individuals.Footnote 23 In expressly enshrining specific identities in law, the state claims to engage in a politics of recognition. As critical race theorist Patricia Williams, writing about the promise of human rights recognition for people of colour, explains: “For the historically disempowered, the conferring of rights is symbolic of all the denied aspects of humanity: rights imply a respect which places one within the referential range of self and others, which elevates one’s status from human body to social being.”Footnote 24 For some, naming “gender identity” and “gender expression” in law has been viewed as a significant symbolic victory. Speaking about Bill C-16,Footnote 25 the federal legislation adding “gender identity or expression” to both the Canadian Human Rights Act and the hate crimes provisions of the Criminal Code,Footnote 26 writer Casey Plett explained that the passage of the law demonstrated that “the majority of the [legislative] chamber informed trans Canadians we were wanted.” Plett further noted that “[the] victory was largely symbolic—and sometimes symbolic victories are really meaningful.”Footnote 27

At the educative level, extending human rights protections holds the promise of sending a message to members of historically marginalized communities that they can seek legal recourse when they experience discrimination. Writing about the educative function of law, socio-legal theorist Frances Kahn Zemans explains that “perceptions of desires, wants, and interests are themselves strongly influenced by the nature and content of legal norms and evolving social definitions of the circumstances in which the law is appropriately invoked.”Footnote 28 As the Northwest Territories’ Standing Committee on Social Programs noted, just before the jurisdiction became the first in Canada to add “gender identity” to its human rights code in 2002: “Although some have argued that this protection is already available through case law, the Committee believes that it is more useful to be explicit about the types of discrimination the Act aims to prevent. Furthermore, by including it in the legislation, the Committee believes we are furthering the educative goals of the Human Rights Act.”Footnote 29 Adding terms in human rights law holds the promise of serving a public education function—for both perpetrators and victims of discrimination. While remaining critical of human rights protections as the sole locus of advocacy, Florence Ashley underscores a series of potential benefits when the educative promise of human rights law is realized: “Widespread knowledge of the presence of anti-discrimination laws might nevertheless have a greater deterrent effect than hate crime laws. … [However,] short of a successful, structured educational campaign, anti-discrimination provisions are bound to retain a modest reach. People cannot be influenced by the law if they do not know it.”Footnote 30

Meanwhile, at the instrumental level, recognizing identities in the context of human rights law holds the promise of remedying individual instances of discrimination on the basis of prohibited grounds. Such claims of discrimination are usually resolved in traditional legal forums, such as courts and tribunals, but may have a series of implications for a variety of state and society actors. A series of recent reported cases demonstrates, in concrete terms, that transgender and/or non-binary claimants have used human rights laws to achieve important goals, including the removal of discriminatory surgical requirements in order to access government-issued identity documents,Footnote 31 and to challenge discriminatory policing practices.Footnote 32 As Ashley puts it, “Anti-discrimination laws are useful. … They make our lives easier and happier.”Footnote 33

In the end, the advent of human rights protections holds the promise of achieving symbolic, educative, and instrumental goals. Whether human rights protections are actually successful in achieving their laudable goals, however, has become a site of contestation within the burgeoning body of trans legal scholarship.

2. Human Rights Critics

Despite the promise of human rights law as a mechanism to redress the pervasive levels of discrimination, harassment, and violence experienced by transgender and/or non-binary communities, scholars have developed a series of powerful criticisms about these recent developments. In much of the writing that is critical of human rights recognition, authors are particularly troubled by the advent and proliferation of hate crime laws. Critics have suggested that hate crime laws fail to deter violenceFootnote 34 and constitute “reactionary” legal instruments.Footnote 35 This critique, which tends to blend concerns about hate crime laws with concerns about anti-discrimination protections, is particularly strong in the United States, where the two instruments have often been legislatively tied together. While Bill C-16 amended both the Canadian Human Rights Act and the hate crimes provisions of the Criminal Code, Canada’s federal, provincial, and territorial human rights tribunals do not have the power to impose criminal sentences—a point that legal experts such as Brenda Cossman have repeatedly made to rectify inaccurate claims propagated by commentators such as Jordan Peterson.Footnote 36

Setting aside the important concerns associated with hate crime legislation, critics have also argued that discrimination-focused human rights law itself suffers from a variety of deficiencies. Among other things, scholars have suggested that human rights laws simplify inequality, uphold existing power structures, and favour the most economically privileged members of trans and/or non-binary communities.

When it comes to the simplification of inequality, critics have noted that human rights law’s individualized approach fails to attend to the realities of systemic discrimination. As Dean Spade argues, human rights law presupposes a “victim” and a “perpetrator” narrative,Footnote 37 such that discrimination is conceptualized as a harm that one actor does to another.Footnote 38 This process of individualization obscures the complex constellation of systemic factors that work to produce particular modes of oppression.Footnote 39 Moreover, human rights law has been criticized for failing to attend to intersectionality, particularly because of its unidimensional insistence on enumerated or analogous grounds. Admittedly, human rights instruments typically allow claimants to argue that they have experienced multiple grounds of discrimination.Footnote 40 For transgender and/or non-binary people of colour or people with disabilities, and those experiencing other intersecting oppressions, however, the legal framework offered by human rights law may still be particularly limiting.Footnote 41

Critics have also suggested that human rights laws can bolster existing state and society power dynamics. As Lamble argues, human rights instruments may contribute to the idea of state innocence. Rather than recognizing the complex ways in which the state itself contributes to oppression, human rights law allows the state to adopt a benevolent position by claiming to provide a mechanism to facilitate the individualized remedying of discrimination.Footnote 42 While human rights law reform may open the door to challenge state action, Spade argues that human rights laws “[tinker] with systems to make them look more inclusive while leaving their most violent operations intact.”Footnote 43 Moreover, the advent of formal human rights protections may allow state actors to publicly proclaim that they are taking action to improve the lived realities of transgender and/or non-binary communities, without the need to make meaningful structural changes.Footnote 44 For example, a critical observer might suggest that it is far easier for the state to add “gender identity” and “gender expression” to human rights instruments than it is to ensure the provision of equitable healthcare for transgender and/or non-binary people.

A third vein of criticism focuses on the reality that privileged members of transgender and/or binary communities are the most likely to be able to access human rights protections. Indeed, one’s ability to access justice is invariably tied to one’s financial resources.Footnote 45 Critics rightly note that human rights complaints are expensive, that human rights commissions rarely have adequate resources to support individual cases, and that tribunals often take long periods of time to render decisions. Especially when “wins” and “losses” in human rights tribunals are used as the barometer to assess whether anti-discrimination protections are effective in remedying discrimination, critics are right to underscore the structural limitations that undermine the promise of human rights protections. Ashley, for example, explains: “Despite every trans person I know having suffered from harassment or discrimination at some point, none has launched an anti-discrimination lawsuit to obtain reparation for the harm they have suffered.”Footnote 46

In short, critics have made important interventions over the past decade, suggesting that the turn to human rights law simplifies equality, upholds existing power structures, and favours the most economically privileged members of transgender and/or non-binary communities. Despite expressing both optimism and criticism about the promise of human rights protections, few have suggested abandoning such approaches altogether. Rather, most scholarship has tended to move in complex ways between the promise of human rights protections and criticism. Building on this literature, we seek to empirically track post-legislative developments, suggesting that human rights reform may open up space for the emergence of norms that allow people to do gender in a variety of ways.

II. The Making of Gender Identity and Gender Expression in Human Rights Commissions, Human Rights Tribunals, and Legislative Debates

While every jurisdiction across Canada had added “gender identity” and/or “gender expression” to their respective human rights instruments as of 2017, the terms remain legally undefined. This has meant that human rights commissions and tribunals have stepped in to provide interpretive guidance on the meaning of these legislative terms. The section below tracks the making of “gender identity” and “gender expression,” as described in a series of statements from human rights commissions, tribunal decisions, and legislative debates. Here, we analyze the tension between expansive definitions of “gender identity” and “gender expression” designed to apply to everyone, and efforts to delineate the terms to only apply to transgender and/or non-binary people. While these sources provide clues about what the terms mean, and to whom they apply, we argue that none have yet to provide definitions that can be used with any degree of consistency in the future.

1. Human Rights Commission Definitions

Across the country, human rights commissions have, as part of their public education mandate, produced policies and other interpretive aids that help define “gender identity” and “gender expression” in human rights law. While these interpretive guides are non-binding on human rights tribunals tasked with adjudicating complaints, they provide provisional guidance and can be used as evidence when considering the meaning of two of Canada’s newest human rights categories. Published after the passage of Toby’s Act in 2012,Footnote 47 the OHRC’s Policy on preventing discrimination because of gender identity and gender expression defines “gender identity” as “each person’s internal and individual experience of gender. It is a person’s sense of being a woman, a man, both, neither, or anywhere along the gender spectrum. A person’s gender identity may be the same as or different from their birth-assigned sex.”Footnote 48 As this passage makes clear, the OHRC constructs “gender identity” as a concept focusing on individual self-identification. By contrast, the OHRC defines “gender expression” as “how a person publicly expresses or presents their gender. This can include behaviour and outward appearance such as dress, hair, make-up, body language and voice. A person’s chosen name and pronoun are also common ways of expressing gender. Others perceive a person’s gender through these attributes.”Footnote 49 In this definition, the OHRC explains that “gender expression” discrimination centers on how individuals present their gender identity to the outside world. Neither definition suggests that transgender and/or non-binary people are the only ones captured by these protections. While OHRC policy documents are construed as educational and therefore not legally binding, human rights tribunals routinely consider them when adjudicating disputes.Footnote 50

2. Human Rights Tribunal Decisions

Since 2012 and the inclusion of “gender identity” and “gender expression” as protected grounds in the Ontario Human Rights Code, a growing body of tribunal decisions have attempted to delineate the parameters of these undefined and amorphous legal constructs. While human rights tribunal decisions are not considered binding authority beyond the bounds of a particular case, they are typically treated as having persuasive value.Footnote 51 One of the ongoing interpretive dilemmas for tribunals has been to whom these terms are designed to apply. Mirroring the larger history of human rights interpretation, where cisgender men argued that they experienced discrimination on the basis of “sex,”Footnote 52 cisgender men have recently started to claim that gendered practices that accord with norms of hegemonic masculinityFootnote 53 ought to be protected by “gender expression” in the Ontario Human Rights Code.

In 2016, for example, the Ontario Human Rights Tribunal (OHRT) released its decision in the case of Browne v Sudbury Integrated Nickel Operations. Footnote 54 In this case, a cisgender man who worked in a mine challenged his employer’s clean-shaven policy. The employer argued that the policy was necessary to ensure the proper functioning of the respirator masks worn by employees. Browne argued that his beard was fundamental to his “gender expression,” and was therefore protected by recent amendments to the Ontario Human Rights Code. The Tribunal summarized Browne’s evidence in the following terms: “He testified that in early October 2012, he decided to grow a mustache and a goatee as a means of expressing his support for the Movember movement, where men grow facial hair in the month of November each year to express their support for men suffering from prostate cancer. The applicant testified that he was moved to do this as a result of the impact of prostate cancer on members of his family.”Footnote 55

In concluding that Browne’s case did not amount to prima facie discrimination on the basis of “gender expression,” the Tribunal gives the reader a glimpse into its interpretive source materials, noting that it has “considered the Ontario Human Rights Commission’s Policy on Preventing Discrimination because of Gender Identity and Gender Expression approved January 31, 2014 (the “Commission Policy”), as well as Hansard, case law and other materials filed by the parties for the purpose of the preliminary hearing.”Footnote 56 It is unclear what “other materials filed by the parties” means in the context of this case.

The Tribunal begins its analysis by surveying a series of human rights decisions standing for the proposition that clean-shaven policies do not constitute a form of sex-based discrimination. The problem with this line of authorities is that Browne did not argue discrimination on the basis of “sex.” Rather, he argued discrimination on the newer and arguably more expansive ground of “gender expression.” Yet the Tribunal justifies its choice to survey this history, explaining that it is “important to consider the issue of whether the ‘clean shaven policy’ is capable of amounting to discrimination against the applicant because of sex, if only to provide a backdrop for consideration of the issue of whether this policy is capable of amounting to discrimination because of ‘gender expression,’ particularly since sex has been a protected ground under the Code since 1972 while ‘gender expression’ was only added as a protected ground in 2012 and has not yet been extensively considered in the case law.”Footnote 57 Put differently, given that “gender expression” remains a new, largely unknown entity, the Tribunal seeks guidance from the much older and well-established body of cases interpreting the meaning of “sex” in the Ontario Human Rights Code.

After surveying the older “sex” discrimination case law, the Tribunal turns to “gender expression” and constructs the new human rights ground in particularly narrow terms. The Tribunal explains: “The issue for me to consider is whether the ground of ‘gender expression’ added as a result of Toby’s Act should be interpreted to protect the right of cisgendered [sic] men to wear beards. In my view, it should not.”Footnote 58 In support of this position, the Tribunal leans heavily on the “abundantly clear” legislative goals of Toby’s Act, which were to “ensure the protection of the rights of transgendered [sic] and gender non-conforming persons.”Footnote 59 In short, because the legislature intended Toby’s Act to protect transgender and/or non-binary communities and Browne is cisgender, he falls outside the scope of the ground of “gender expression.”Footnote 60

Without finding a case of prima facie discrimination, the Tribunal proceeds to leave the door open for other cisgender claimants, just not Browne, to argue that they have experienced discrimination on the basis of “gender expression”: “The specific examples cited in the Commission’s Policy where the ground of ‘gender expression’ may extend beyond the protection of transgendered [sic] and gender non-conforming persons arise out of factual circumstances that are very different from those in the instant case. Whether or not the ground of ‘gender expression’ applies in the types of factual circumstances referenced in the Commission Policy, or whether these circumstances are already covered by other protected grounds, is a matter for consideration at a later time in the appropriate context.”Footnote 61 Put differently, the Tribunal is not prepared to definitively rule on whether a cisgender person could ever successfully argue that they had experienced discrimination on the basis of “gender expression.”

The narrow interpretation afforded to “gender expression” in Browne was recently cited approvingly in Barksey v Four Corners Medical Walk In Clinic/Northwood Medical Clinics Inc. Footnote 62 In this case, a cisgender man unsuccessfully argued that he had experienced “gender expression” and “disability” discrimination for his “stereotypically male” demeanour in a medical clinic. Relying on the reasoning in Browne that Toby’s Act was only designed to apply to transgender and/or non-binary people, the Tribunal reasoned:

There is no dispute that the applicant is not a transgender or gender non-conforming person. Instead, he is a “cisgender” man, meaning he was born male and self-identifies as a man. Not only is the applicant not transgender or gender non-conforming, but he is seeking protection under the Code for engaging in gender conforming expression—that is expression that may be viewed as stereotypically male. In my view, the ground of gender expression cannot reasonably be interpreted to protect the right of cisgender men to express themselves in ways that may be perceived to be stereotypically male. To interpret the ground of “gender expression” in this way is thoroughly inconsistent with, and would do violence to, the important purposes of Toby’s Act which added the ground of gender expression to the Code.Footnote 63

In Barksey, the Tribunal suggests that the legislature never designed the ground of “gender expression” to capture those engaged in so-called “gender conforming expression.” This claim, of course, begs the question of what constitutes “gender conforming” expression, and how it might be assessed in future cases. In both Browne and Barksey, the “universalizing” impulse of “gender expression,” which suggests that everyone does gender in their everyday lives, has been abandoned in favour of a “minoritizing” approach.Footnote 64 The “minoritizing” approach suggests that the newly-minted ground is only designed to capture a small number of people who ‘really are’ transgender and/or non-binary, or, more curiously, gender non-conforming, and that “gender conforming” people are excluded from this protected ground.Footnote 65 Gender non-conforming people, in common usage, are not necessarily transgender and/or non-binary.

The Tribunal’s reasoning in both cases is troublesome for at least four reasons. First, there is an expansive line of human rights case law to suggest that rights-conferring instruments ought to be given a large and liberal interpretation.Footnote 66 It seems difficult to see how, in both Browne and Banksey, the Tribunal has adhered to this legal principle.

Second, the OHRC policy constructs “gender expression” broadly, explicitly noting that it is designed to capture “how a person publicly expresses or presents their gender,” including “behaviour and outward appearance such as dress, hair, make-up, body language and voice.”Footnote 67 Indeed, in Browne, the Tribunal admits that passages from the OHRC underline the universalizing, performative impulses of “gender expression,” such that protections may extend beyond people who are transgender and/or non-binary. The Tribunal explains: “While the vast majority of the Commission’s Policy is clearly directed at the rights afforded to transgendered [sic] and gender non-conforming individuals, there are some specific suggestions in the Policy that the ground of ‘gender expression’ may extend beyond this community.”Footnote 68

Third, we disagree with the Tribunal’s assertion in Browne and Barksey that “gender expression” is only capable of applying to transgender and/or non-binary people. We start from the position that all people have a “gender expression,” and are therefore protected from discrimination under the Ontario Human Rights Code. This is not to say, however, that the forms of hegemonic masculinity at issue in Browne and Barksey should necessarily be conceptualized as targets of discrimination on the basis of “gender expression.” While theorizing the nature of discrimination goes beyond our purposes here,Footnote 69 it is now well-established that Canadian human rights law is designed to guard against the operation of prejudice or stereotyping. Moreover, the existence of pre-existing or historical disadvantage experienced by groups identified in human rights law instruments may serve as a useful heuristic for courts and tribunals tasked with adjudicating claims of discrimination.Footnote 70 Given that there is little on the record in both Browne and Barksey to suggest that cisgender men engaged in forms of hegemonic masculinity are subject to pre-existing or historical disadvantage, let alone prejudice or stereotyping, our view is that these cases could be resolved by finding that no discrimination had occurred. Resolving the cases this way would have avoided the troubling suggestion that “gender expression” protections should be limited to only apply to transgender and/or non-binary people.

Fourth, restricting “gender expression” protections to people who are transgender and/or non-binary places the Tribunal in the troubling position of deciding the boundaries of transgender as a category, one case at a time, by saying yes or no to “gender expression” claimants on the basis of whether Tribunal members perceive them to fall within that category. It is conceivable that this hypothetical body of case law defining “transgender” could be misused in the future to the detriment of transgender and/or non-binary people whose “trans-ness” exceeds or defeats what is understood by the Tribunal.

3. Legislative Debates

Beyond human rights commission definitions and recent tribunal decisions, tensions about the universalizing impulses of “gender expression” were not reflected in the Hansard debates surrounding the passage of Toby’s Act in Ontario in 2012, with lawmakers preferring to make optimistic statements about the promise of human rights law reform.Footnote 71 While lawmakers regularly cited the discrimination, harassment, and violence experienced by transgender and/or non-binary communities, they did not suggest that the protections were designed to be afforded a narrow interpretation. As Member of Provincial Parliament Jane McKenna, describing Toby’s Act, explained:

And yet, under the current language of the Ontario Human Rights Code, the equalities and freedoms that most of us enjoy, and which far too many of us take for granted, are spelled out clearly for some and are implied for others. Bill 33 addresses that shortcoming. It amends the Human Rights Code to specify that every person has a right to equal treatment without discrimination because of gender identity or gender expression with respect to services, goods and facilities; accommodations; contracting; employment; and membership in a trade union, trade or occupational association or self-governing profession. The bill also amends the code to specify that every person has a right to be free from harassment because of gender identity or gender expression with respect to accommodation and employment.Footnote 72

The same cannot be said, however, about debates surrounding the passage of Bill C-279, the precursor to Bill C-16. Bill C-279, a federal private member’s bill that made it through the House of Commons but ultimately died on the order paper when an election was called, initially sought to add “gender identity” and “gender expression” to both the Canadian Human Rights Act and the hate crimes provisions of the Criminal Code. Footnote 73 Fearing that the legislation would fail unless it was more narrowly circumscribed, some proponents of the legislation made the difficult decision to excise “gender expression” from the law altogether.Footnote 74 Allyson M. Lunny argues that the tendency on the parts of courts, tribunals, and lawmakers to prefer fixed, narrowly bounded grounds reaches beyond the Canadian experience, extending into other jurisdictions such as the United States.Footnote 75

While a variety of actors in human rights commissions, tribunals, and legislatures have provided clues about the meaning of “gender identity” and “gender expression,” analyses that focus on a narrow set of constitutive actors are likely to produce a narrow set of conclusions about the terms’ meaning and implications. In the section that follows, we turn to school boards as spaces that engage in the everyday meaning-making of “gender identity” and “gender expression.” It is by turning to these sites, we argue, that we arrive at a far more nuanced portrait about the emerging interpretive landscape of “gender identity” and “gender expression,” along with the promise that legislative reform might improve the experiences of transgender and/or non-binary communities and beyond. This study builds on the existing trans legal studies scholarship by empirically demonstrating how human rights protections may open up space for the making of new everyday norms and practices.

III. Case Study: The Making of Gender Identity and Gender Expression in Ontario’s Public Secular School Boards

In order to attend to the complex ways that a variety of actors participate in bringing human rights categories to life outside courts and tribunals, this section examines how Ontario’s secular school boards have responded to the passage of Toby’s Act in 2012 in a series of policy documents. By carefully reading these policies, much can be learned about how human rights protections affect, and are shaped by, the everyday work of actors in schools. This section begins by setting out a brief description of our methodology, followed by an analysis of how “gender identity” and “gender expression” have been constructed by Ontario’s English-language public secular school boards since the passage of Toby’s Act in 2012.

1. Methodology

Data collection was conducted systematically, one school board at a time, by two research assistants (the third and fourth authors) working under the supervision of the second author. Data collection began with Google searches, internal website searches and targeted manual searches for documents containing the terms “gender identity” or “gender expression,” as well as the school board name or common abbreviations. We applied a number of strict sampling criteria to each resulting document. In order to be included, a document had to be: 1) offering explicit direction or guidance to actors within one of Ontario’s thirty-four English-language public secular school boards; 2) authored by the given school board or its agent (not an individual school within a board); 3) written or revised since 2012, when Toby’s Act was passed; 4) written in English; and 5) publicly available. Taken together, our searches and application of sampling criteria yielded 209 documents for analysis.

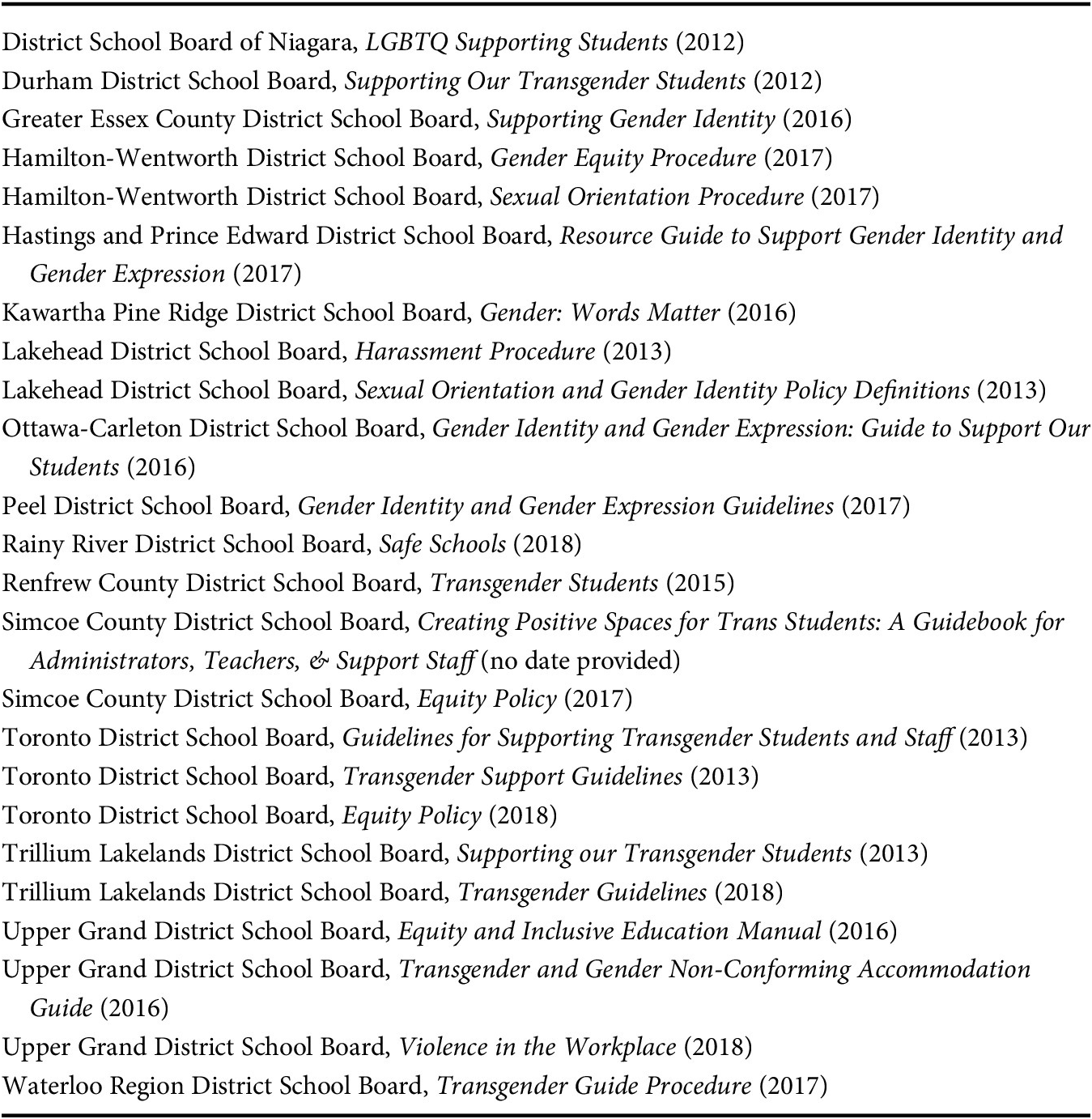

For the purposes of this paper, we analyzed the explicit definitions of “gender identity” and “gender expression” found in the data set of policy documents. In total, there were twenty-four documents containing explicit definitions of “gender identity” and seventeen documents containing explicit definitions of “gender expression.” The documents containing explicit definitions were produced between 2012 and 2018.Footnote 76 These explicit definitions tended to be located in glossaries or informative sidebars. We analyzed each definition for its degree of fidelity to the definitions given by the OHRC’s Policy on preventing discrimination because of gender identity and gender expression. The definitions were then assigned one value on a five-point fidelity scale, with a rating of five indicating that the definition was directly copied and pasted from the OHRC policy, and a rating of one indicating that the definition was totally out of step with the OHRC policy. Two policies contained two different definitions of “gender identity” within a single document; these policies were therefore assigned two fidelity scores.Footnote 77 The definitions were grouped based on their similarity to one another. For example, the Durham District School Board policy’s definition of “gender expression” has a fidelity rating of one; however, it is a verbatim match with the definition of “gender expression” provided by the Trillium Lakelands District School Board. Once this process had been completed for both definitions, we made a series of inferences regarding how school boards are interpreting the definitions provided by the OHRC.

2. Findings

In the aftermath of the passage of Toby’s Act,Footnote 78 one might expect that Ontario’s secular school boards would simply copy and paste definitions from the OHRC’s Policy on preventing discrimination because of gender identity and gender expression on the advice of their legal counsel, who would have reviewed all board-level policies for legal compliance. A critical observer might conclude that a school board’s decision to publish a policy in the aftermath of a legislative amendment constitutes little more than an attempt to mitigate risk—adding “gender identity” and “gender expression” to the Ontario Human Rights Code, the story might go, raised the specter of liability, such that school boards needed to develop policies to better ensure that they were complying with their new legal obligations. While mitigating legal risk may indeed be shaping the creation of policies seeking to comply with Toby’s Act, our findings suggest that such an explanation may be incomplete.

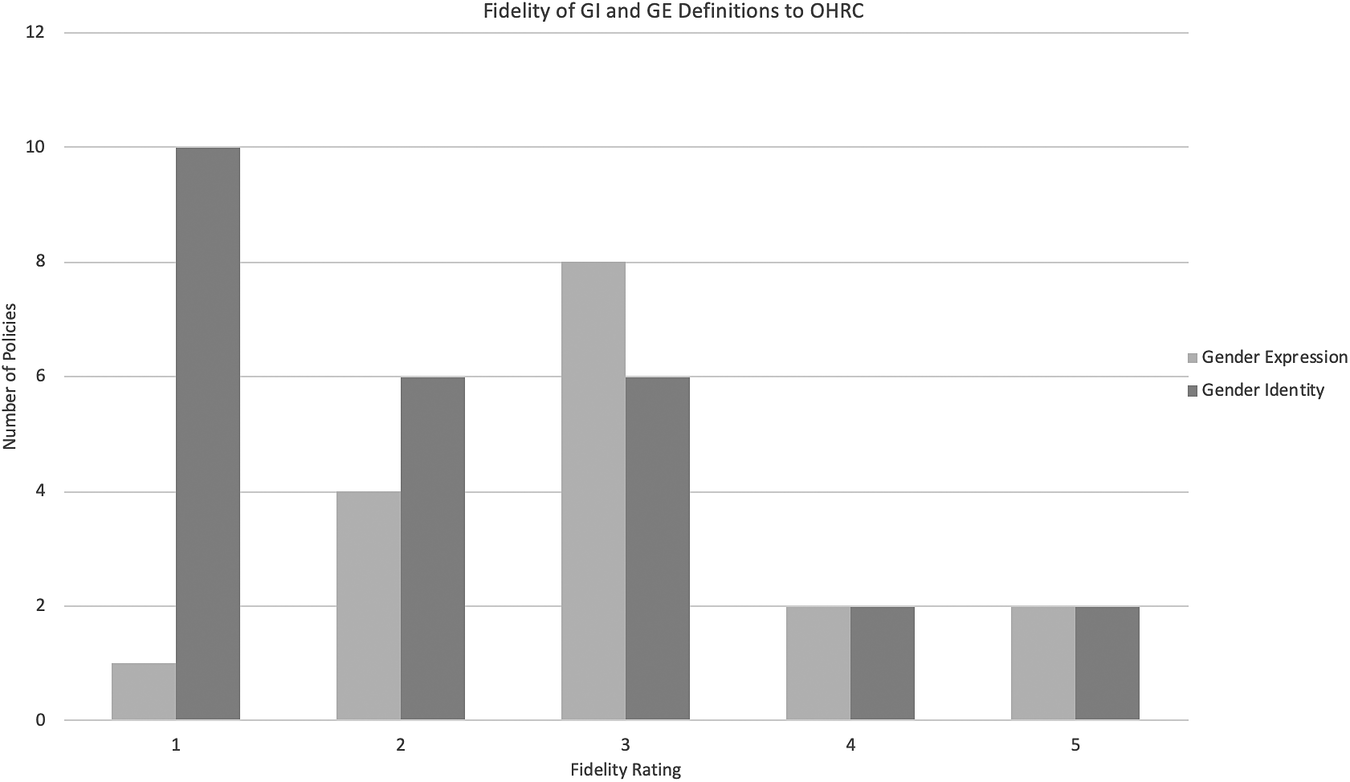

Given school boards’ lack of adherence to the definitions offered in the OHRC policy, we suggest that such policies are doing more than simply attempting to comply with the law. Rather, these policies are shaping “gender identity” and “gender expression” in ways that alter their meaning and, potentially, how they are preventatively or reactively applied in school settings. Furthermore, we suggest that such policies have the power to shape our collective understanding of what these human rights categories mean because the Ontario public education system is so vast—indeed, this system may be one of the primary public vehicles in Ontario for communicating what these new human rights grounds mean and do not mean, including who they do and do not protect. While this paper focuses on Ontario, we suspect that a similar dynamic may be playing out in other provinces and territories across Canada. Figure 1 is a chart summarizing the fidelity score assigned to each definition of “gender identity” and “gender expression.”

Figure 1 Fidelity of “gender identity” and “gender expression” definitions to Ontario Human Rights Code.

Beyond the fidelity score assigned to each definition, the educative function of the newly crafted policies is also underscored by the typographical features of the various policies, which indicate that almost all were designed to be public facing and to educate parents, teachers, students, and other interested parties about these grounds. In short, these documents seem to be doing more than simply mitigating the risk associated with human rights complaints. For example, published in February 2016, the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board’s Gender Identity and Gender Expression: Guide to Support our Students, is clearly designed to serve an educative function. While the policy makes several references to the Ontario Human Rights Code, revealing that the text is being mediated by legal discourse, the text is consistently educative. Beyond its bright and colourful features, the policy also contains a number of graphics designed to explain the meaning of terms such as “gender identity,” “gender expression,” “gender spectrum,” and “gender fluidity.” One graphic uses blue and pink colours in an effort to explain the concept of “gender fluidity,” with a series of stick figures with various parts of their bodies painted in blue and pink (Figure 2). This is an odd and erroneous representation of “gender fluidity,” as its common usage in transgender-spectrum communities refers to fluidity in a person’s gender across time and not different parts of the same individual’s body being variously gendered at the same time. Interestingly, this graphic was also included in several other policies. In another, the authors use the common pedagogical illustration of the “Genderbread Person”Footnote 79 in an effort to distinguish between the concepts of “identity” (located in the brain), “expression” (located on the body), “attraction” (located on the heart), and “sex” (located on the genitals) (Figure 3). Framed in formal legal terms, the document uses the graphic to distinguish between the protected human rights grounds of “gender identity” (identity), “gender expression” (expression), “sexual orientation” (attraction), and “sex” (sex). Mitigating the risk of human rights liability seems to be, at best, a secondary purpose, with public education being the primary goal of this brightly coloured, accessible document.

Figure 2 Gender Spectrum and Gender Fluidity. Source: Ottawa-Carleton District School Board, Gender Identity and Gender Expression: Guide to Support our Students (2016): 7.

Figure 3 The Genderbread Person. Source: Ottawa-Carleton District School Board, Gender Identity and Gender Expression: Guide to Support our Students (2016): 12.

A careful reading of every post-Toby’s Act policy document containing an explicit definition of “gender identity” and/or “gender expression” also suggests that drafters were clearly aware of their duty to comply with the Ontario Human Rights Code but often constructed definitions in ways that did not readily map onto those set out in the OHRC’s 2012 policy. Across the documents included in this study, there were twenty-four instances of policy documents including explicit definitions of “gender identity” and seventeen of “gender expression.” Of the seventeen policies containing explicit definitions of “gender expression,” only two—the Renfrew County District School Board’s 2015 Transgender Students policy and the Rainy River District School Board’s 2018 Safe Schools—directly copied the definition from the OHRC’s 2012 policy.

In most of the seventeen definitions of “gender expression,” the policies were moderately faithful to the definitions set out in the OHRC’s 2012 policy. Like the OHRC’s 2012 policy, and unlike the Tribunal’s recent decisions in cases such as Browne and Barksey, every explicit definition constructed “gender expression” in universalizing terms. For example, the Peel District School Board’s 2017 Gender Identity and Gender Expression Guidelines defines “gender expression” as:

…how a person publicly presents or expresses their gender. This can include behaviour and outward appearance such as dress, hair, make-up, body language, and voice. A person’s chosen name and pronoun are also common ways people express their gender. Others may perceive a person’s gender through these attributes. All people, regardless of their gender identity, have a gender expression and they may express it in any number of ways. For trans people, their chosen name, preferred pronoun and apparel are common ways they express their gender. People who are trans may also take medically supportive steps to align their body with their gender identity.Footnote 80

Unlike the Tribunal’s decisions in cases such Browne and Barksey, the policy authors explicitly state that “gender expression” is a term designed to capture “all people…in any number of ways.” This clarifies the OHRC’s 2012 definition, while moving far afield from Browne, where the Tribunal excluded the applicant from the ground of “gender expression” because he was “someone who self-identifies as male (gender) and was also born as a man (sex).”Footnote 81 The definition offered by the Peel District School Board is also far more expansive than the decision in Barksey, where the Tribunal excluded the applicant from the ground of “gender expression” because he was a cisgender man engaged in so-called “gender conforming expression.”Footnote 82 This definition, formed in the education context, suggests the emergence of a disjuncture between recent efforts on the part of the Tribunal to constrain the expansive potential of “gender expression” and how school boards are interpreting their post-Toby’s Act obligations.

In other instances, definitions of “gender expression” did not draw from the 2012 OHRC policy at all. The Greater Essex County District School Board’s 2016 Supporting Gender Identity policy, for example, defines “gender expression” as: “The various ways that we communicate our gender identity to others, for example, social roles, clothing, body language, hair styles, speech patterns, and voice pitch, given name, etcetera. Often this communication is ascribed to us at a young age and imposed on us through social norms and values.”Footnote 83 This definition appears to be more expansive than both the OHRC’s 2012 policy and recent statements from the Tribunal in Browne and Barksey—the use of the words “we,” “our,” and “us” suggests an underlying commitment to “gender expression” as a universalizing construct applying to all members of the school community, regardless of whether or not they identify as transgender and/or non-binary. In other policies where the definitions did not accord with the OHRC’s 2012 policy, the authors emphasize the cultural specificity of “gender expression.” The Toronto District School Board’s 2018 Equity Policy, for example, defines “gender expression” as “the way an individual expresses their Gender Identity (e.g. in the way they dress, the length and style of their hair, the way they act or speak, the volume of their voice, and in the choice of whether or not to wear make-up). Understandings of gender expression are culturally specific and will change over time.”Footnote 84

Turning to our dataset of twenty-four explicit definitions of “gender identity,” we found only two policies containing definitions that had been directly copied from the OHRC’s 2012 policy. These are the same policies where the definitions of “gender expression” are also borrowed directly from the OHRC.Footnote 85 While the majority of the definitions appear to have drawn from the OHRC, all but three contained additional text, seemingly in an effort to better explain the meaning of “gender identity.” Importantly, none of the definitional changes were designed to constrain the use of “gender identity” as something that only applies to transgender and/or non-binary people. When changes were made to the OHRC’s definition, they invariably expanded the scope of the term to include more people. For example, the Greater Essex District School Board’s 2016 Supporting Gender Identity policy describes “gender identity” as: “A person’s intrinsic sense of self in relation to gender. We all have a gender identity and live within a society that recognizes a gender binary that provides structure to our social roles that come with power, responsibilities, and privilege to a greater or lesser extent.”Footnote 86 In this definition, we see the authors striving to define “gender identity” as applying to everyone. Similarly, the Upper Grand District School Board’s 2016 Equity and Inclusive Education Manual describes “gender identity” as being “based on attributes reflected in the person’s psychological, behavioural and/or cognitive state; may also refer to one’s intrinsic sense of manhood or womanhood. It is fundamentally different from, and not determinative of, sexual orientation.”Footnote 87 While this definition bears little resemblance to the one offered by the OHRC, it suggests that the category is capable of capturing a broad array of ways in which students and adults in schools are engaged in doing gender.

While the Tribunal in Browne and Barksey attempts to contain “gender identity” so as to not include cisgender people based on the “abundantly clear” legislative record,Footnote 88 there is no suggestion in any of these forty-one explicit definitions of “gender identity” or “gender expression” that these terms ought to be construed in such a limited fashion. This disjuncture, we suggest, underscores the need to attend to sites beyond courts and tribunals in an effort to better understand the plural, contradictory meaning of these terms.

IV. Conclusion: The Aftermath of Human Rights Protections

By studying the development of policies by Ontario’s English-language public secular school boards in the aftermath of Toby’s Act in 2012, we have sought to trace the emergence of parallel norm-making in the education context. In doing so, we have argued that our collective understanding of the efficacy of adding terms such as “gender identity” and “gender expression” to law as a means of opening space for people to be able to live free from discrimination may be limited when we overemphasize the decisions of courts and tribunals in our analyses. Human rights legislation shapes norms and practices in ways that extend far beyond these decisions, such that studies of the utility of “gender identity” and “gender expression” law reform efforts ought to consider analyzing a broader set of constitutive actors.

At the same time, we admit that our analysis of the creation of post-Toby’s Act education policies tells us little about who was included, and who might have been left out, of both policy design and ongoing implementation processes. Moreover, studying these policies does not tell us who might continue to be left at the margins of transgender and/or non-binary legal change, particularly in an era when we have witnessed a series of regressive gender and sexuality interventions, including changes to the provision of sexual education.Footnote 89

While the pervasive levels of discrimination, harassment, and violence experienced by transgender and/or non-binary people may surface in a relatively small number of decisions rendered by courts and tribunals, our claim in this paper is that attending to sites such as school boards might allow us to think about the aftermath of human rights law reforms in new ways. As our empirical study suggests, adding “gender identity” and “gender esxpression” to human rights laws may constitute more than an empty symbolic gesture—law reforms may hold the promise of opening up space for the emergence of norms that allow people to do gender in a variety of ways.

APPENDIX

Policy Documents Containing Explicit Definitions of “Gender Identity” and/or “Gender Expression”