Introduction

In the United States, more than two million patients are hospitalized annually because of chest pain suggestive of myocardial ischemia. However, a coronary event is demonstrated in <20% of this population.Reference Amsterdam, Lewis and Yadlapalli 1 Accurate identification of the cause of acute chest pain is a challenge to emergency physicians. Previous studies show that about 2%–8% of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) were discharged from emergency departments (EDs) inadvertently.Reference Pope, Aufderheide and Ruthazer 2 Out of these, approximately 25% may develop adverse cardiac events before returning to the hospital.Reference McCarthy, Beshansky and D’Agostino 3 The desire for sensitivity in evaluating chest pain patients has led to their undergoing prolonged ED observation, admission and/or non-invasive or invasive testing, despite a low overall event rate. Multiple rapid-rule-out protocols have been developed to facilitate rapid ED discharge of low-risk patients.Reference Christenson, Innes and McKnight 4 – Reference Scheuermeyer, Wong and Yu 7 Two surveys done with physicians showed that acceptable miss-rate for AMI was between 1% and 2% for these rapid rule-out protocols.Reference Than, Herbert and Flaws 8 - Reference MacGougan, Christenson and Innes 9

The Vancouver Chest Pain (VCP) Rule recommends early discharge for a group of patients who are at low risk of adverse events to be discharged within 2 hours of ED arrival.Reference Christenson, Innes and McKnight 4 The main cardiac enzyme marker used in the original VCP Rule was creatinine kinase – muscle/brain isomer (CK-MB). However, as troponin assays have improved in their sensitivity and precision over the years,Reference Kavsak and Worster 10 – Reference Than, Cullen and Aldous 11 recent studies have replaced CK-MB with troponin as the cardiac enzyme marker in the VCP Rule.Reference Greenslade, Cullen and Than 5 , Reference Cullen, Greenslade and Than 6 Greenslade et al.Reference Greenslade, Cullen and Than 5 recommended modifying the VCP Rule if troponin was to be used as the only biomarker.

The new VCP Rule was subsequently developed by Scheuermeyer and team,Reference Scheuermeyer, Wong and Yu 7 where the rule stated that for early discharge of chest pain patients, patients needed to have 1) a normal initial electrocardiogram (ECG), troponin ≤99% at 2 hours, no previous known history of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or nitrate use and chest pain increasing with palpation; or 2) a normal initial ECG, troponin ≤99% at 2 hours, no previous known history of ACS or nitrate use, chest pain not increasing with palpation, age <50 years old, and non-radiating pain (neck, jaw, or arm). Cullen et al.Reference Cullen, Greenslade and Than 6 further validated the study and found 99.1% sensitivity and 16.3% specificity. However, these studies were all conducted in a Caucasian population; there have been no other similar validation studies of the new VCP Rule in the Asian population.

Objectives

We thus aimed to assess the performance of the VCP Rule for Asian patients presenting with chest pain at the ED. We specifically looked at the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and admission rates when applying these rules in a local setting.

Materials And Methods

This study is a secondary analysis of a prospective data set, which involved a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing stress myocardial perfusion imaging (SMPI) for chest pain patients.Reference Lim, Anantharaman and Sundram 12 In the RCT, eligible patients were randomized into the intervention (SMPI) or control (clinical assessment) protocol at presentation in the ED. Randomization was 2:1 for SMPI versus clinical assessment. The population was chest pain patients presenting to the ED Chest Pain Unit in a large urban centre from 27 August 2000 to 1 May 2002. The Hospital Ethics Board approval was obtained for the study.

The Singapore General Hospital (SGH) is Singapore’s oldest and largest acute tertiary hospital and national referral centre. SGH accounts for about one third of total acute hospital beds in the public sector and about a quarter of acute beds nationwide. Annually, about 60,000 patients are admitted to our wards and another 600,000 attend to our specialist outpatient clinics. The ED sees approximately 300 to 500 visits a day.

Patients were admitted to the chest pain unit and included in the study if they were at least 25 years of age, presented to the ED with stable chest pain and with an initial 12-lead ECG non-diagnostic for myocardial ischemia and AMI. There was no lower age limit if the patient had any coronary risk factors such as diabetes mellitus or family history of young AMI (less than 50 years old). Written informed consent was taken from these patients.

Patients were excluded if the ECG was diagnostic for AMI or acute myocardial ischemia (which was defined as new Q wave, ST elevation, or depression greater than 1 mm or 0.1 mV in two or more contiguous leads), or if there was congestive cardiac failure or hypotension associated with chest pain. If a clinical syndrome of persistent chest pain consistent with unstable angina was present, these patients were admitted to the coronary care unit or a telemetry bed and were excluded. Also excluded were patients with a past history of proven coronary artery disease, and presenting with chest pain that was more severe or frequent than previous angina episodes.

Once the patient was enrolled, he or she was put on continuous ECG monitoring, and 10 ml of blood was drawn at 0, 3, 6 hours after arrival at the ED for myoglobin, CK-MB (Elecsys CK-MB STAT assay), and TnT (3rd Generation Elecsys Troponin T STAT assay) analysis. Previous hospital case record and ECGs of the patient, if available, were retrieved. A detailed prospective collection of presenting history, examination, ECG, and laboratory results was done by dedicated research coordinators as part of the larger RCT. This included results of subsequent admissions, stress testing, angiography, and clinical outcomes. Follow-up medical case records of all participants were reviewed, and participants were followed up at 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, and 6 months for any adverse cardiac events such as cardiac-related death, ventricular fibrillation, and myocardial infarction. Patients were contacted by phone at 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, and 6 months after discharge for measurement of adverse cardiac events (primary end point). Patients who could not be contacted by phone were contacted by letter. If the patients could not be contacted, records from the Registry of Deaths were screened to trace for the final outcomes.

The VCP Rule was then applied retrospectively to this cohort of chest pain patients, and they were categorized as unsuitable or suitable for early discharge based on the rule.

Outcomes

All cases with missing data at decision points were assigned as unsuitable for early discharge. The main outcome measures were cardiac events (death, ventricular fibrillation, myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock, or acute pulmonary edema), angioplasty, or coronary artery bypass within 30 days of enrolment.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were done using R 3.0.2. In the descriptive analysis, the differences in qualitative outcomes were determined using the chi-square and the Fisher exact tests. A two-sample t-test was performed when normality and homogeneity assumptions were satisfied; otherwise, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used for quantitative outcomes. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were calculated where appropriate.

Results

A total of 1690 eligible chest pain patients presented to the ED between 27 August 2000 and 1 May 2002.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients enrolled in the study. Mean age was 53.0 years (SD 12.5), with 59.2% males; 69.8% were Chinese, 11.3% Malays, 17.3% Indian, and 1.7% other races. The patient’s medical history and clinical presentation are also shown.

Table 1 Comparison of baseline characteristics by cardiac event

CABG=coronary artery bypass graft; IHD=ischemic heart disease; HR=heart rate; SBP=systolic blood pressure; CK-MB=creatinine kinase – muscle/brain isomer; TnT=troponin T; ECG=electrocardiogram.

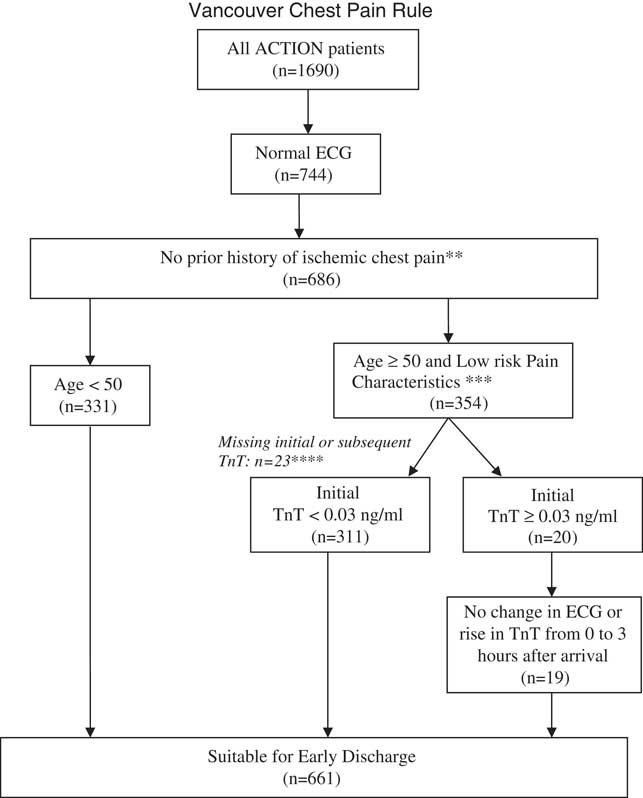

Figure 1 shows the characteristics of the patients according to the VCP Rule; 661 patients were found to fulfil the VCP criteria for low risk and early discharge. This gave an “early” discharge rate of 39% for the chest pain cohort. According to the rule, 331 (19.6%) patients would have avoided blood testing and 311 (18.4%) needed one TnT test only. However, we noted that, in this study, a second TnT was taken 3 hours after the first sample (instead of 2 hours in the original rule); 19 (1.1%) patients of at least 50 years old had an initial TnT >/=0.03 ng/ml but no ECG or serum-marker increase at 3 hours. These patients would still have waited >4 hours before “early” discharge, factoring in the wait time needed to obtain laboratory results.

Figure 1 Chest pain early discharge rule.

T-wave flattening is the only acceptable ST-T abnormality. Note: Patients with suspicion of other causes of chest pain (e.g., pulmonary embolus, aortic dissection) should be investigated independent of this clinical prediction rule.

** Prior ischemic chest pain is defined as a past known diagnosis of MI or angina, previously prescribed nitroglycerine or a clear history of effort-related angina.

***Low risk Pain Characteristics is defined as pain not radiating (arm/neck/jaw) OR increasing with a deep breath OR increasing with palpation

****All cases with missing data at decision points are assigned to “Unsuitable for early discharge.”

Table 2 shows the 7-day and 30-day cardiac events of the entire patient cohort. AMI (6.5% v. 6.7% for 7-day and 30-day cardiac events, respectively) was the most common cardiac event occurring amongst the patient cohort.

Table 2 7-day and 30-day cardiac events of a patient cohort

AMI=acute myocardial infarction; PTCA=percutaneous transcoronary angioplasty; CABG=coronary artery bypass graft.

Table 3 shows the diagnostic accuracy of the rule for cardiac events. Table 4 shows the diagnostic accuracy of the rule for cardiac events, including angioplasty and bypass surgery. Of those for early discharge, 24 had cardiac events and 13 had angioplasty or bypass at 30 days, compared to 91 and 41, respectively, for those unsuitable for discharge. This gave the rule a sensitivity of 79.1% for cardiac events and 78.1% for cardiac events, including angioplasty and bypass. Specificity was 40.4% and 41%, and NPV was 96.4% and 94.4%, respectively.

Table 3 Diagnostic accuracy of the Vancouver Chest Pain Rule for subsequent cardiac events (30-day)

Table 4 Diagnostic accuracy of the Vancouver Chest Pain Rule for subsequent cardiac events, including need for angioplasty and coronary bypass surgery (30-day)

PTCA=percutaneous transcoronary angioplasty; CABG=coronary artery bypass graft.

Regarding the 24 patients whom the rule indicated were safe for early discharge but had cardiac events (Table 3), all 24 had no prior history of ischemic chest pain. Five were below 50 years of age, and 19 were above 50 years of age but had low-risk pain characteristics. Of the 19 with low-risk pain, 5 had an initial TnT <0.03 ng/ml, and 14 had an initial TnT ≥0.03 ng/ml but no serial change in ECG or rise in TnT from 0 to 3 hours after arrival.

Discussion

In this study, we found that the VCP Rule had only moderate sensitivity and poor specificity for adverse cardiac events. With a NPV of less than 100%, this means that a small proportion of patients sent home with early discharge would still have adverse cardiac events (this is, however, a common finding in most chest pain rules).

We found a lower sensitivity and negative predictive power than in the original VCP study, which was reported at 98.8% and 99.0%, respectively.Reference Christenson, Innes and McKnight 4 Greenslade et al.’sReference Greenslade, Cullen and Than 5 study, which replaced CK-MB with troponin as the cardiac enzyme marker in the original VCP Rule, also reported higher sensitivity (91%) but similar NPV (94.4%) as our study. Specificity was higher in our study as compared to Christenson’sReference Christenson, Innes and McKnight 4 and Greenslade’sReference Greenslade, Cullen and Than 5 studies.

Methodologically, our study is similar to Cullen’s and Scheuermeyer’s studies where the new VCP Rule with troponin assay was retrospectively applied to the chest pain cohort. Despite the similarity in methodology, our study achieved a much lower sensitivity but higher specificity as compared to Cullen’sReference Cullen, Greenslade and Than 6 (sensitivity: 99.1%, specificity: 16.3%) and Scheuermeyer’sReference Scheuermeyer, Wong and Yu 7 (sensitivity: 99.2%, specificity: 23.4%). Several reasons may explain the differences in results between our study and theirs such as recruitment hours, outcomes definition, and ethnic differences in the population. In Cullen’s and Scheuermeyer’s studies, patients were recruited during office hours only (weekdays, 0800–1700) or during the day and evening (1100–1900); our study’s recruitment was from Sunday 0800 to Saturday 0359. There may be differences in standard of care (e.g., availability of physicians/nurses in the chest pain unit, quality of care associated with staff fatigue) and subsequently outcomes when patients present during after-office hours as seen in studies examining mortality rates in patients with AMI who presented after office-hours.Reference Pirrallo, Aufderheide and Provo 13 Also, there may be differences between the patient population in this study and the patients in both Scheuermeyer’sReference Scheuermeyer, Wong and Yu 7 and Cullen’sReference Cullen, Greenslade and Than 6 validations. Specifically, the exclusion of patients with known coronary disease and those with high-risk angina presentation might be different from practice in North America. These should be kept in mind when comparing results between studies.

It is also important to point out that, in these previous studies, the main outcome measure was a 30-day diagnosis of AMI or definite unstable angina.Reference Christenson, Innes and McKnight 4 , Reference Cullen, Greenslade and Than 6 , Reference Scheuermeyer, Wong and Yu 7 The diagnosis of definite unstable angina in Christenson’s study required rest pain greater than or equal to 20 minutes, and at least one of the following related to the presenting symptoms: 1) troponin increase 0.1 to 0.99 mg/L, 2) dynamic ECG changes consistent with ischemia in two contiguous leads (dynamic ST depression 0.5 mm or dynamic deep T-wave inversion), 3) a coronary angiogram with greater than 70% lesion plus hospital admission for ACS, or 4) a positive stress test result (radionuclide scan echo or ECG stress test) plus admission for ACS.Reference Christenson, Innes and McKnight 4 For our study, we have chosen to use proven adverse cardiac events as our main outcome measure, which we felt was more conservative and clinically important. Despite this, we note the relatively poorer performance of the rule in our population. As far as we know, none of the revascularizations in our study were elective/previously planned procedures, because patients were excluded if they had a previous angiogram or SMPI/echo test within 18 months.

Lastly, previous studiesReference Chaturvedi 14 have suggested that ethnic differences exist in the presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and responses for cardiovascular diseases. ChaturvediReference Chaturvedi 14 observed that accurate diagnosis of cardiovascular causes for upper body discomfort in South Asians was more challenging as compared to Europeans; South Asians were more frequently investigated for upper gastrointestinal disorders. South Asians with AMI were also more likely to be categorized as non-typical than Europeans. Self-reported symptoms such as pain increasing with palpation might be highly subjective and influenced by cultural factors. Ischemic heart disease also tended to occur at a younger age in South Asians as compared to Europeans, and apart from conventional risk factors (e.g., smoking, obesity), glucose intolerance, waist-to-hip ratio, fasting triglyceride, and insulin were also found to be predictors of ischemic heart disease in South Asians.Reference Chaturvedi 14 These factors may suggest that using history of ischemic chest pain, low-risk pain characteristics in the VCP Rule may not be most suited for an Asian population.

Patients with chest pain of uncertain origin often undergo a period of observation varying from 6 to 12 hours, serial cardiac enzyme sampling,Reference Ellestad, Startt-Selvester and Stanton 15 – Reference Peacock, Emerman and McErlean 19 ECGs, and possibly provocative stress testing.Reference Schaeffer, Brennan and Hughes 20 As many hospitals face situations with decreased inpatient capacity resulting in “bed block,”Reference Trzeciak and Rivers 21 management of chest pain in the ED can possibly decrease in-hospital admissions for evaluation of chest pain.Reference Goldman 22 However, the pressures of ED overcrowdingReference Trzeciak and Rivers 21 , Reference Bradley 23 – Reference Walters 28 mean that ED resources can become stretched due to the lengthy and costly evaluations of chest pain patients in order to “rule out” ACS.

It is in such a setting that accelerated chest pain assessment protocols are attractive.Reference Christenson, Innes and McKnight 4 , Reference Aroney, Dunlevie and Bett 29 , Reference Grzybowski, Zalenski and Ross 30 The challenge is to safely identify the subset of low-risk patients who do not require such lengthy and costly rule-out evaluations.Reference Amsterdam, Lewis and Yadlapalli 1 , Reference Schillinger, Sodeck and Meron 31 , Reference Selker, Beshansky and Griffith 32 The VCP Rule shows some promise in identifying this group. However, the rule is still limited by the requirement for sampling of cardiac enzymes at 2 hours post initial evaluation, which practically means that the patient needs to be observed in the ED for a minimum of a 3- to 4-hour period.

Limitations of this study include that, although it was prospective data collection, application of the VCP Rule was based on a hypothetical application of this rule in our population. This population was also highly selected in that patients with “high risk” symptoms would usually be directly admitted to the hospital, based on symptoms alone, irrespective of their laboratory findings, and would not have been included in this study population. Also, there may be some confounding due to the fact that, in the data set, two-thirds of the validation cohort had undergone SMPI within 24 hours of ED discharge (58% of patients who did not meet the criteria for early discharge underwent SMPI, whereas 62% of patients who met the criteria for early discharge underwent SMPI). However, we feel that this actually increases the validity of the study findings, because we have definitive testing and outcomes for most of the data set. The number of missing data was relatively small and would not have affected the analysis. There were 23 cases with “missing” initial or subsequent TnT, usually related to delayed blood draw. These cases with missing information were treated as “not suitable” for early discharge based on a conservative approach. Also, we note that this study was performed using the previous generation of TnT assay. The performance of the VCP Rule might be improved by the new high sensitivity troponin assays currently available.

Despite the limitations discussed, this study demonstrates the utility of validating clinical scoring systems in local settings. We intend to follow up with a prospective observational study, likely modifying the new VCP Rule and comparing with other possible clinical rules.Reference Antman, Cohen and Bernink 33 , Reference Backus, Six and Kelder 34 This could be in combination with point-of-care testing. However, these rules may have more utility when combined with clinical pretest probabilities as indicated by our study.

Conclusion

We found the VCP Rule to have only moderate sensitivity and poor specificity for adverse cardiac events in our population. With an NPV of less than 100%, this means that a small proportion of patients sent home with early discharge would still have adverse cardiac events. Further study is needed regarding the utility of the rule in clinical practice.

Financial Support: This study was supported by grants from the National Medical Research Council, Ministry of Health, Singapore [Grant Numbers NMRC/0517/2001].

Competing interests: None declared.