INTRODUCTION

Text messaging is ubiquitous in modern communication and has been widely adopted by the general population. When considering other modes of communication, text messaging is efficient, mobile, low cost, and has the advantage of instant transmission.Reference Purcell, Entner and Henderson 1 Text messaging has become the most used method of daily communication between family and friends, overtaking speaking on a mobile phone.Reference Smith 2 Text messages are also perceived as being less invasive to daily lives than phone calls and more convenient for exchanging information.Reference Kaplan 3 This method of communication has been effective in the health care setting to provide appointment reminders, facilitate self-management of chronic illnesses, and encourage medication adherence.Reference Car, Gurol-Urganci and de Jongh 4 - Reference Liu, Abba and Alejandra 6 Several reviews of the literature have illustrated wide application and potential for mobile phones to increase access to health care; enhance the efficiency of service delivery; improve diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation; and support public health.Reference Car, Gurol-Urganci and de Jongh 4 - Reference Liu, Abba and Alejandra 6

Despite the widespread application of text messaging to facilitate health care delivery, there is a paucity in the literature supporting the use of text messaging to facilitate clinical research, specifically to assist in research participant follow-up.Reference Brueton, Tierney and Stenning 7 Incomplete or missing outcome data from patients lost to follow-up or patients who withdraw from study participation present a major threat to the internal and external validity of a clinical trial. The study results may be biased if patients are unable to follow up because of factors related to the outcome of interest.Reference Akl, Briel and You 8 Therefore, researchers should anticipate and plan a pragmatic approach to decrease study attrition at the stage of trial design and patient accrual. Text messaging, proven effective in the health care delivery setting, offers a novel means to improve clinical research study attrition.

The objective of this study was to determine whether text messaging study participants involved in an ongoing randomized controlled trial (RCT) resulted in a lower rate of attrition compared to conventional telephone follow-up.

METHODS

This was a nested cohort analysis of research participants enrolled in an RCT assessing minor traumatic brain injury (MTBI) discharge instructions. The trial took place in the emergency department (ED) of an academic tertiary care hospital in Toronto, Ontario (annual census 55,000) from October 2014 to May 2015. Patients ages 18 to 64 years presenting to the ED with a Canadian Emergency Department Information System (CEDIS) chief complaint of a head injury or suspected concussion occurring within 24 hours were eligible for study inclusion. ED nurses screened potential patients, and once eligibility was confirmed by the attending physician, informed written consent was obtained from trained research personnel (when available) or by the emergency physician or nurse. Patients were excluded if they had an acute intracranial injury identified on a head computed tomography (including but not limited to subarachnoid hemorrhage, skull fracture, intracranial contusion, or epidural hematoma), a Glasgow Coma Scale score of <15, were cognitively impaired, did not speak English, or did not have a telephone. The study protocol was approved by the institutional research ethics board (REB).

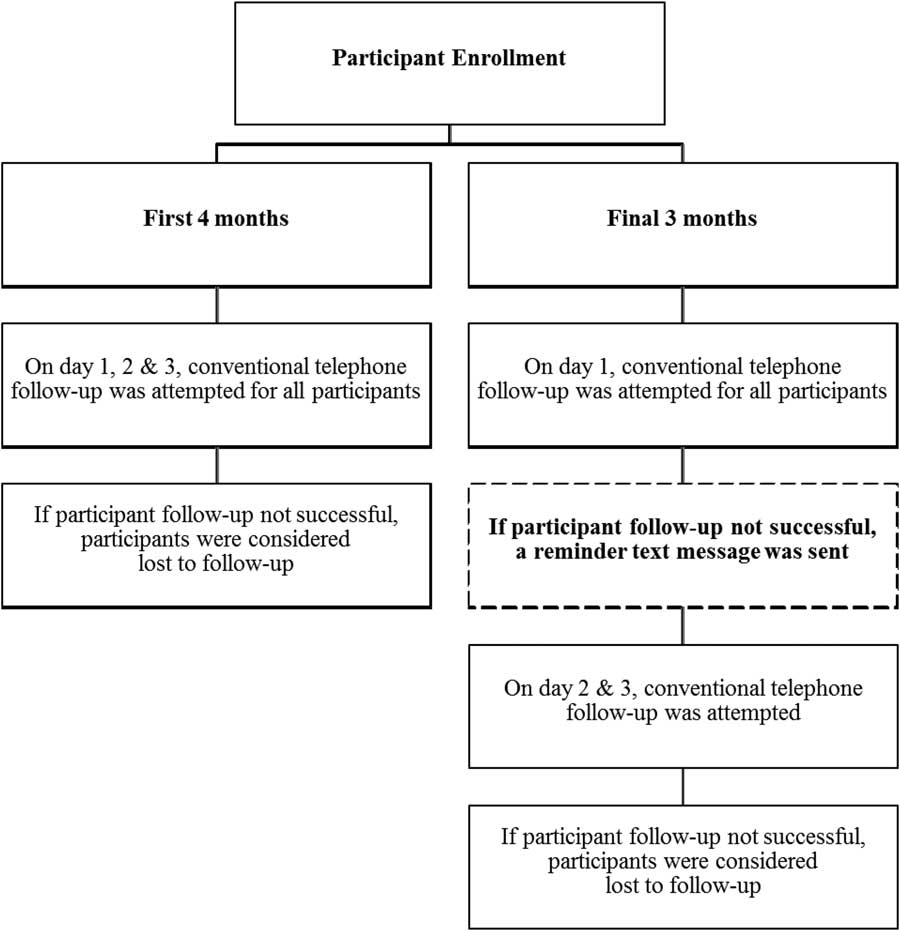

Patients were contacted by telephone at 2 weeks and 4 weeks following their index ED visit to repeat a symptom questionnaire and document other MTBI-related outcomes. During the first 4 months of study follow-up, participants were contacted by a conventional telephone call only. If telephone contact was not successful on the first day of the scheduled follow-up, telephone attempts were made on 2 more days. Because of participant attrition at the study’s midpoint, REB approval was applied for and received to send text message reminders to patients regarding their upcoming telephone calls. The revised consent form asked patients if they were willing to be contacted by a text message in the event that telephone contact was not successful on the first day of the scheduled follow-up. Research personnel were provided a study-specific mobile phone to both send and receive text messages to participants. Text messages were sent and responded to, if applicable, during daytime hours on Monday to Friday. Study participants were not reimbursed for any charges that they may have incurred for the text messages. If contact was not made after three telephone attempts and a text communication, patients were considered lost to follow-up (Figure 1). No other changes to the protocol were made during the study period. The text message was structured as follows: “Hi [name of study participant]. Recently you enrolled in a research study at Mount Sinai Hospital. A research assistant will be calling you today to complete a questionnaire. Please note that this will be a blocked number. If we are unable to get in touch today, please suggest to us a better time to call, or call 416-586-4800, ext. 5959 to speak to the research assistant. Thank you for your participation.” No personal health information was exchanged in the text messages.

Figure 1 Follow-up methods for enrolled patients.

The primary outcome was the proportional difference in loss to a follow-up at 2 weeks between the group receiving text messages and those receiving conventional telephone follow-up. The difference in loss to follow-up at 4 weeks was also measured, and anecdotal experiences were noted. Data were entered directly into a study-specific Microsoft Excel database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington). Descriptive statistics were summarized using means and standard deviations or proportional differences with 95% confidence intervals where appropriate. Loss to follow-up between the group receiving texts and the group not receiving texts was compared using a Fisher exact test or chi-square test, where appropriate. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS (v.9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

A total of 118 patients were enrolled in the study (40 received text messages, and 78 underwent conventional follow-up). The mean age was 35.2 (SD 13.7) years, and 43 (36.4%) were male. Patient characteristics between the groups were similar (Table 1).

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of enrolled patients

CT=computed tomography; CTAS=Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale; MVC=motor vehicle crash; SD=standard deviation.

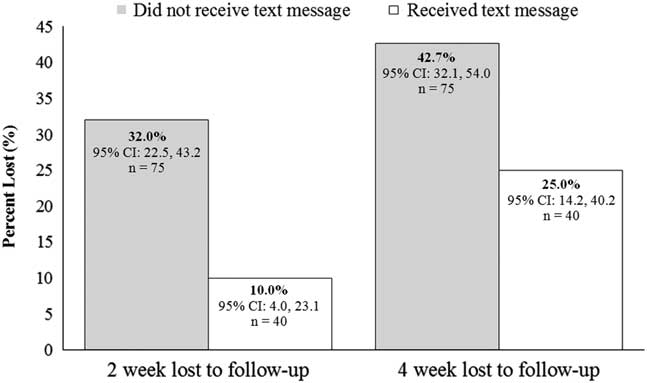

During the period of conventional follow-up, three participants withdrew from the study. Of the remaining 75 participants, 24 (32.0%) at 2 weeks and 32 (42.7%) at 4 weeks were unable to be contacted. Of the 40 participants receiving a reminder text message, 4 (10.0%) at 2 weeks and 10 (25.0%) at 4 weeks were unable to be contacted. Overall, text messaging study participants decreased attrition by 22% (95% CI: 5.9%, 34.7%) and 17.7% (95% CI: -0.8%, 33.3%) at 2- and 4-week follow-ups, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2 The proportion of patients lost to follow-up at 2 and 4 weeks between those who received conventional telephone follow-up compared to those receiving text messages. Text messaging decreased attrition by 22% (95% CI: 5.9%, 34.7%) and 17.7% (95% CI: -0.8%, 33.3%) at 2 and 4 week follow-up, respectively.

Although not formally captured, patients often replied to text messages with a request to reschedule their follow-up telephone interview to a more convenient time, often to not interrupt work obligations. Two examples of these scheduling request text messages are as follows:

“I am working now. Can I call you at noon?”

“Just about to step into a meeting at 9:15. I am free at 10:15. You can call at that time.”

Additionally, patients expressed preferences towards text messaging, as one patient responded, “It’s better you text. It’s more efficient. I will call [the research assistant] today.”

DISCUSSION

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether text messaging study participants involved in an ongoing randomized trial resulted in a lower rate of attrition compared to conventional telephone follow-up. Our findings in this ED cohort suggest that text message reminders of upcoming telephone follow-ups decreased the rate of attrition, resulting in a more efficient study completion and potential for less biased results.

Planning a pragmatic approach to decrease study attrition is important when designing a clinical trial. The failure to account for all included participants at the end of the trial presents a major threat to the internal validity of the study findings.Reference Akl, Briel and You 8 A recent meta-analysis of three studies assessed the effectiveness of sending electronic mail (email) prompts to 437 trial participants in an effort to improve response rates to postal questionnaires. The authors concluded that the use of electronic prompts increased the response rate (69.5% in the electronic prompt group v. 60.7% in the control group; ∆8.8%; 95% CI: -0.11%, 17.7%) and reduced the time of response (23 days in the electronic prompt group v. 33 days in the control group; hazard ratio=1.27; 95% CI: 1.11, 1.47).Reference Clark, Ronaldson and Dyson 9 The improved response rates following email reminders are consistent with our findings, and although text messaging and email are different modes of electronic reminders, both are useful in decreasing study attrition.

With respect to text messaging study participants, one study has reported that the effectiveness of text messaging pre-notification reminders for postal questionnaires did not improve response rates. Starr et al.Reference Starr, McPherson and Forrest 10 evaluated two interventions aimed at increasing response rates to postal questionnaires within a large RCT in the UK: pre-notification through short messenger service (SMS) text prior to sending the initial mailing of trial questionnaires versus no pre-notification; for non-responders to the initial mailing of the questionnaires, an email reminder (containing a hyperlink to complete the questionnaire online) versus a postal reminder. In this 2×2 factorial trial, participants were randomly assigned to the pre-notification comparison or the reminder comparison or both. SMS text pre-notification of a questionnaire delivery and email delivery of questionnaire reminders did not improve response rates.Reference Starr, McPherson and Forrest 10 It is possible that text messaging in our study was more effective because follow-up occurred the same day, using the same telephone number.

Text messaging to improve follow-up for treatment or clinical reassessment has been shown to be effective in the ED setting. Arora et al.Reference Arora, Burner and Terp 11 performed an RCT of ED patients with an outpatient follow-up scheduled at the time of an ED discharge. Patients who received an automated text message reminder were more likely to attend their scheduled follow-up visit (72.6% in the intervention group compared with 62.1% in the control group; ∆ 10.5%; 95% CI: 0.3%, 20.8%; number needed to treat 9.5).Reference Arora, Burner and Terp 11 Wolff et al.Reference Wolff, Balamuth and Sampayo 12 conducted an RCT of adolescent females diagnosed with pelvic inflammatory disease, which found that patients who received standard discharge instructions plus text message reminders were more likely to receive recommended follow-up care within 72 hours of the ED discharge compared to patients who received standard discharge instructions (relative risk 2.9, 95% CI: 1.4, 5.7; number needed to treat 4, 95% CI: 1.4, 5.7).Reference Wolff, Balamuth and Sampayo 12 These ED-specific findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating improved follow-up adherence in other health care settings when text messaging was used.Reference Liu, Abba and Alejandra 6

This study is not without limitations. The main limitation of this study is that it is a nested cohort analysis within a small RCT conducted at a single academic centre. These findings may not be generalizable to other centres. Future studies should investigate text messaging as a means to decrease study attrition as the focus of the investigation. It is possible that unmeasured confounders (i.e., socioeconomic and employment status) contributed to the differences in loss to follow-up between the two groups. This study did not address other methods that could be used to mitigate loss to follow-up, such as monetary incentives, which have been previously shown to improve response rates.Reference Brueton, Tierney and Stenning 7 However, the use of monetary incentives carries both practical and ethical considerations, particularly in the context of a clinical trial. Given that email has also been effective at decreasing study attrition for postal questionnaires, email may be another effective, low-cost option to use going forward.Reference Starr, McPherson and Forrest 10 However, text messaging is an easily-adopted, methodological intervention that can be implemented using a low-cost data mobile phone plan.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, few strategies in randomized trials have been investigated to reduce loss to follow-up. In our ED cohort participating in a randomized trial, text message reminders of upcoming telephone follow-ups decreased the rate of attrition. Our findings suggest that text messaging is an easily-adopted, low-cost technique that can improve study participation and follow-up, particularly in the low-continuity ED setting.

Competing interests: None declared. This study was funded by the College of Family Physicians of Canada Janus Research Grant Training Level 1.