BACKGROUND

Teaching diagnostic reasoning to medical trainees is important but challenging to accomplish. Instructors must identify and correct learner deficiencies in medical content knowledge, patient assessment abilities, and problem-solving skills. The recommended methods for optimally teaching diagnostic reasoning include:

-

1) Early case-based teaching, which allows students to create illness scripts, aiding in the development of essential content knowledge.Reference Bowen 1 , Reference Schmidt, Norman and Boshuizen 2

-

2) Teaching with multiple similar cases (mixed practice) to encourage students to compare the differentiating features of illnesses with similar presenting symptoms.Reference Bowen 1

-

3) Active student involvement in the problem-solving process to facilitate metacognition.Reference Kassirer 3

-

4) Ensuring that case practice mimics the clinical setting as much as possible as this is where trainees will apply their knowledge.Reference Eva 4

Errors in diagnostic reasoning have been implicated as a challenge to patient safety, particularly in emergency departments (ED).Reference Newman-Toker and Pronovost 5 , Reference Shojania, Burton, McDonald and Goldman 6 Additionally, concerns have been raised about the inefficiency of the clinical environment in providing systematic exposure to specific clinical conditions for both undergraduate and postgraduate trainees.Reference Norman 7 , Reference Sherbino and Norman 8 The importance of work-based learning through actual patient encounters cannot be overstated. However, with a random collection of clinical exposures during training, not all trainees experience the repeated practice that develops diagnostic acumen across a spectrum of clinical conditions. Geoff Norman suggests the addition of “carefully engineered simulated settings” for clinical learning as a solution.Reference Norman 7

It has also been suggested that simulation may be useful for improving diagnostic education to reduce errors.Reference Newman-Toker and Pronovost 5 Clinical teachers should explicitly foster the ability of students to incorporate both analytical and non-analytical reasoning strategies into their diagnostic approach.Reference Eva 4 , Reference Sklar 9 For preclinical medical students, realistic patient encounters can contribute to the experiences they may draw upon for non-analytical reasoning strategies such as pattern recognition.

PURPOSE

We designed a practice-based simulation program to teach diagnostic reasoning to undergraduate medical students. These sessions were facilitated by experienced emergency physicians and allowed the students to practice diagnosis in a supervised setting with feedback.

DESCRIPTION OF THE INNOVATION

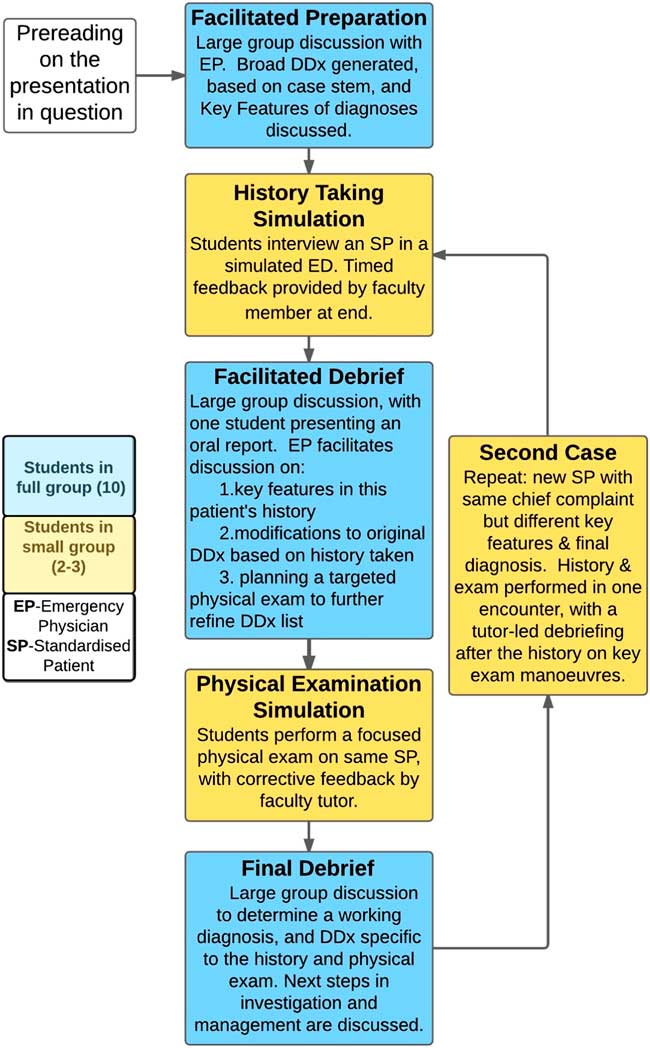

In these sessions, the second-year medical students were exposed to patient actors in a simulated ED environment with one of three acute care presentations: chest pain, abdominal pain, or headache. These complaints were chosen by consensus as common ED presentations that were synchronized with the content of the second-year curriculum. For example, the chest pain sessions (featuring patient actors with symptoms suggestive of pulmonary embolism and aortic dissection) were taught in the autumn during the circulation and respiration course. Each of the three sessions exposed students to two different patient actors with the same chief complaint but different key features and diagnosis (for example, a middle-aged female actor presenting with a headache and features typical of viral meningitis, and then a second patient actor with features typical of subarachnoid hemorrhage). After learning about the key diagnoses in their pre-reading, the students were given a stem and then guided through both an interview with the standardized patient and a physical exam, with ongoing faculty feedback. The session was designed to model the diagnostic reasoning process explicitly and is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Flow chart of clinical reasoning session design.

Students were encouraged to identify key features from the history and physical exam to discriminate between possible diagnoses, an evolution for them from a “head to toe” rote physical examination. After every stage, students were stopped and asked what they thought the diagnosis was and why. Students were given feedback by tutors on their identification of key features, their physical examination skills, and the manoeuvres chosen for their targeted physical examinations. Having two cases with the same clinical complaint but contrasting diagnoses allowed the learners to engage in mixed practice, maximizing efficiency in the development of illness scripts for these presentations.Reference Bowen 1 Realism and a sense of urgency were provided by attaching the actors to monitors, showing simulated vital signs reflective of the diagnosis, such as hypoxia and tachycardia. Props were used (such as spray water indicating diaphoresis), and the actors were asked to be restless, uncomfortable, or tachypneic as appropriate during the interviews.

A cohort of 50 medical students assessed the program at two time points: immediately following the sessions, and in an 18-month follow-up survey during the clerkship, 4 months prior to graduation. Immediately afterwards, student evaluations were universally positive. Students commented that experiencing the process of diagnostic reasoning in action had allowed them to understand “what a doctor actually does,” unmasking a process previously unrecognized by them. Students labelled them as “the best sessions in medical school,” appreciating the high yield of simulated realistic clinical practice. The purpose of the follow-up survey was to understand whether (and how) these sessions might have changed perceived diagnostic reasoning ability and patient care during the clerkship. Fifty students (50%) responded to the four-question survey. Their prompted comments following the questions were recorded in free text, without cueing for content or theme, and a thematic analysis of comments was performed by two separate raters. If the raters differed, the themes were assigned after discussion to reach consensus. The results are shown in Table 1. These responses suggest that the sessions were memorable to students and significant in helping them develop an approach to assessing undifferentiated patient complaints during the clerkship.

Table 1 Results from anonymous medical student survey 18 months after the last simulation session on diagnostic reasoning

DISCUSSION

With the advent of competency-based medical education, the need to document specific learner outcomes throughout students’ development is increasingly important. This simulation-based learning program was developed for novice learners to introduce the process of diagnostic reasoning and allow coached, deliberate practice of this skill. Medical students participating in the program had self-reported gains in understanding of diagnostic reasoning and perceived improved diagnostic ability, which persisted 18 months later. While this curricular innovation was developed for preclinical medical students, its design principles could be transferable to more advanced learners using modified cases and higher-level assessment.

Most Canadian emergency medicine (EM) programs have incorporated simulation into their training, with learning outcomes most commonly being the development of resuscitation and crisis resource management skills.Reference Ilgen, Sherbino and Cook 10 Simulation is also effective for learning procedural skills, particularly infrequently performed critical procedures.Reference Ilgen, Sherbino and Cook 10 This program demonstrates the potential utility of the simulated clinical environment as a complementary venue to the busy ED where novice learners’ ability in diagnostic reasoning can be fostered and assessed.

SUMMARY

We describe a practical teaching series that builds upon existing medical education literature to teach diagnostic reasoning skills to medical trainees. The use of a simulated clinical environment, mixed case practice, and immediate feedback from emergency physicians is shown to be a feasible framework, which has benefited medical students in their clinical clerkship. These sessions could be scaled and tailored to advance the diagnostic reasoning of trainees at higher levels, including those in postgraduate EM training programs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the faculty, staff and standardized patients at the Queen's Clinical Simulation Centre and the Queen’s Clinical Teaching Centre for their support and assistance.

Competing interests: None declared.