Introduction

Hip and femur fractures are common in patients presenting to the emergency department (ED). Pain management is often a challenge due to the advanced age, comorbidities, and increased sensitivity to side effects from systemic analgesics in this population. These patients are at a significant risk of delirium due to under-treatment of their pain,Reference Morrison, Magaziner and Gilbert 1 but are also susceptible to becoming delirious from the use of opiate analgesics, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often contraindicated due to drug-drug interactions and risk of side effects. Therefore, regional nerve blocks performed in the ED are increasingly recommended for pain control in hip fracture patients to reduce the need for systemic analgesics, prevent delirium, and improve pain control prior to definitive treatment.

There are three described methods of providing regional nerve blocks for hip and femur fractures: the traditional femoral nerve block (FNB), the 3-in-1 femoral nerve block (3-in-1 FNB), and the fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB). The traditional FNB involves injecting local anesthetic directly surrounding the femoral nerve within the neurovascular bundle of the groin. This can be converted to a 3-in-1 FNB by placing pressure distal to the needle at the time of injection, which allows the anesthetic to track superiorly and also anesthetize the obturator and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves.Reference Winnie, Ramamurthy and Durrani 2 The FICB indirectly anesthetizes the same three nerves as the 3-in-1 FNB by inserting a needle lateral to the neurovascular bundle and filling the fascia iliaca compartment with a large volume of dilute local anesthetic, which theoretically tracks superiorly towards the lumbar plexus.Reference Dalens, Vanneuville and Tanguy 3

The adoption of regional nerve blocks for hip and femoral neck fractures in the ED has been slow in North America, where the use of these techniques has largely been limited to a small number of providers with advanced training. A 2012 survey of three Toronto, Ontario–area hospitals found that only 33% of attending emergency physicians ever performed regional nerve blocks for hip fractures, and only 6% performed them “often” or “almost always.”Reference Haslam, Lansdown and Lee 4 In contrast, in the United Kingdom, regional nerve blocks are used quite commonly in the ED, with a 2009 survey finding that 55% of EDs regularly use regional anesthesia techniques for hip and femur fractures.Reference Mittal and Vermani 5 In order to find out whether regional nerve blocks should be more widely used in the ED, this systematic review intends to determine whether regional nerve blocks (FNB, 3-in-1 FNB, and FICB) effectively reduce pain, reduce the need for IV opiates, and reduce the risk of complications compared to standard pain management for adult ED patients with an acute hip or femoral neck fracture.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of the literature with a search on January 17, 2014, using MEDLINE (1946–2014), EMBASE (1947–2014), CINAHL (1960–2014), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Issue 12 of 12, December 2013). The complete search strategy is provided in the Appendix. Additional articles were screened by searching the references of all articles selected for full-text review. There were no language restrictions.

Inclusion criteria were randomized controlled trials involving adult patients (16 years or older) with an acute hip or femoral neck fracture who had a single injection FNB, 3-in-1 FNB, or FICB. The injection must have been performed preoperatively and a pain score reduction recorded. Comparison must have been made to any method of “standard pain management,” which was defined as opiates, acetaminophen, or NSAIDs. Articles were excluded if they were not a randomized controlled trial, if the nerve block was performed immediately prior to surgery, if the patient also received an epidural or spinal anesthetic in conjunction with the regional nerve block, if a continuous nerve block catheter was placed, or if the study only enrolled patients with mid-shaft femoral fractures.

After the initial literature search, the titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors (BR and PP) for inclusion in the full-text review. Kappa values were calculated for inter-observer reliability. After selecting articles for full-text review, both authors independently extracted data from each article onto a data extraction form. This form included reasons for inclusion/exclusion, key study characteristics, demographics, risk of bias, and results. Key study characteristics recorded included the specialty and level of training of the physician performing the block, the needle guidance technique used, and any co-analgesics administered. Risk of bias was assessed for each study using the Cochrane Collaborations tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials.Reference Higgins, Altman and Gøtzsche 6

After the completion of data extraction, kappa values were calculated for inter-observer reliability for final article selection. Any differences in article selection, data extraction, or risk of bias assessment between the two authors (BR and PP) were resolved by consensus. If consensus could not be reached, a third author (MW) was designated to mediate a final decision. In cases where information was unclear or not reported, attempts were made to contact the primary authors of the studies for clarification.

The primary outcome was a reduction in visual analog scale pain score with the FNB, 3-in-1 FNB, or FICB, compared to standard pain management. Secondary outcomes included a reduction in parenteral opioid use and complication rates. Pre-specified complications of interest were nausea/vomiting, respiratory depression, delirium, nerve injury, intravascular injection, and local anesthetic toxicity, although all reported complications were recorded.

The intent was to perform a meta-analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes if possible, assuming the results were reported in similar ways and the studies were clinically homogenous enough that a meta-analysis was considered valid. There was also an a priori subgroup analysis planned to see whether there were any differences between the primary and secondary outcomes, in studies that used ultrasound guidance versus other methods of needle guidance. The PRISMA guidelines were used in structuring the reporting of this systematic review.Reference Liberati, Altman and Tetzlaff 7

Results

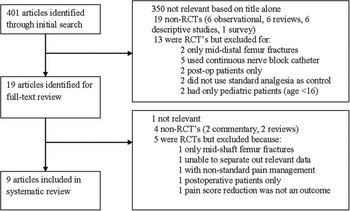

Our initial literature search identified 401 studies, after duplicates were removed. After screening the titles and abstracts of these 401 studies, 19 were selected for full-text review and potential inclusion. Inter-observer reliability for the initial screening phase was moderate with a kappa of 0.61 (95% CI, 0.39–0.82). After full-text review, nine were selected for inclusion in the systematic review with a kappa score of 0.79 (95% CI, 0.51–1.00). A study flow diagram, including the reasons studies were excluded, is illustrated in Figure 1. There were no additional studies identified from the references of included studies.

Figure 1 Study Flow Diagram, including reasons for exclusion at each stage

Of the included studies, two utilized the traditional FNB,Reference Haddad and Williams 8 , Reference Murgue, Ehret and Massacrier-Imbert 9 four used the 3-in-1 FNB,Reference Beaudoin, Haran and Liebmann 10 - Reference Kullenberg, Ysberg and Heilman 13 and three used the FICBReference Foss, Kristensen and Bundgaard 14 - Reference Monzón, Vazquez and Jauregui 16 . Baseline demographics were similar between studies, with a weighted mean age of 80.6, 79.5, and 76.4 years in the FNB, 3-in-1 FNB, and FICB studies respectively. The gender ratio of patients across studies was also similar, with 75.7%, 72.0%, and 67.3% of patients being female in the FNB, 3-in-1 FNB, and FICB studies respectively.

The only study at an overall low risk of bias was the article by Beaudoin et al.,Reference Beaudoin, Haran and Liebmann 10 whereas every other article was at a moderate to high risk of bias, as described in Figure 2. The risk of bias came largely from a lack of double blinding in six out of nine studies;Reference Haddad and Williams 8 , Reference Murgue, Ehret and Massacrier-Imbert 9 , Reference Fletcher, Rigby and Heyes 11 - Reference Kullenberg, Ysberg and Heilman 13 , Reference Fujihara, Fukunishi and Nishio 15 however, the studies by Beaudoin et al.,Reference Beaudoin, Haran and Liebmann 10 Foss et al.,Reference Foss, Kristensen and Bundgaard 14 and Monzón et al.Reference Monzón, Vazquez and Jauregui 16 attempted to blind patients and clinicians by performing sham nerve blocks. Five studies also suffered from inadequate blinding of outcome assessment,Reference Murgue, Ehret and Massacrier-Imbert 9 , Reference Graham, Baird and McGuffie 12 - Reference Fujihara, Fukunishi and Nishio 15 and four studies included patients who were later unaccounted for in the final resultsReference Haddad and Williams 8 , Reference Fletcher, Rigby and Heyes 11 , Reference Graham, Baird and McGuffie 12 , Reference Monzón, Vazquez and Jauregui 16 .

Figure 2 Risk of bias chart detailing the risk of each domain of bias in each individual study.

All of the included randomized controlled trials were small, ranging in size from 33 patients to 154 patients (Table 1). Two-thirds of the studies (66.7%) enrolled 50 or fewer patients. The most commonly used local anesthetic for performing the FNB and 3-in-1 FNB was bupivacaine 0.5%, which ranged in dose from 20–30 mL. The FICB studies all used different local anesthetics, which made direct comparison of these studies difficult. Only one studyReference Beaudoin, Haran and Liebmann 10 used ultrasound guidance, whereas the remainder used either landmark techniqueReference Haddad and Williams 8 , Reference Fletcher, Rigby and Heyes 11 , Reference Foss, Kristensen and Bundgaard 14 - Reference Monzón, Vazquez and Jauregui 16 or nerve stimulator guidanceReference Murgue, Ehret and Massacrier-Imbert 9 , Reference Graham, Baird and McGuffie 12 , Reference Kullenberg, Ysberg and Heilman 13 . An emergency physician or resident performed the nerve block in five out of nine studiesReference Murgue, Ehret and Massacrier-Imbert 9 - Reference Graham, Baird and McGuffie 12 , Reference Monzón, Vazquez and Jauregui 16 . In only one studyReference Beaudoin, Haran and Liebmann 10 did the authors report any prior experience performing the block. In the studies that reported how physicians were trained to perform the nerve blocks, the procedure was learned quickly and easily.

Table 1 Summary of key study characteristics

n=total number of patients in treatment and standard analgesia group

Due to variable methods of reporting final outcome results, missing statistics, and clinical heterogeneity between studies, a meta-analysis could not be performed. Authors of various studies were contacted when necessary, but missing data were either unavailableReference Fletcher, Rigby and Heyes 11 , Reference Graham, Baird and McGuffie 12 or we were unable to locate the authorsReference Haddad and Williams 8 , Reference Kullenberg, Ysberg and Heilman 13 . Therefore, data are presented as a qualitative synthesis to summarize individual studies.

For the primary outcome of visual analog score pain reduction with a regional nerve block, eight out of nine studiesReference Haddad and Williams 8 - Reference Fletcher, Rigby and Heyes 11 , Reference Kullenberg, Ysberg and Heilman 13 - Reference Monzón, Vazquez and Jauregui 16 concluded there was an equal or superior benefit with a nerve block compared to standard pain management (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Pain score reduction over time in all studies. Error bars represent standard deviations where information was available

A summary of the conclusions of each article follows:

Femoral Nerve Block: Haddad et al.Reference Haddad and Williams 8 found the nerve block arm experienced less pain at 15 minutes and two hours, but not at eight hours. Murgue et al.Reference Murgue, Ehret and Massacrier-Imbert 9 found a decrease in pain with the FNB that was superior to either IV morphine or IV acetaminophen/NSAID combination.

3-in-1 Femoral Nerve Block: Beaudoin et al.Reference Beaudoin, Haran and Liebmann 10 concluded the sum of the differences in pain scores between the 3-in-1 FNB and placebo was lower in the nerve block group after four hours (p=0.001). Fletcher et al.Reference Fletcher, Rigby and Heyes 11 found lower aggregate mean pain scores with the 3-in-1 FNB up to 16 hours. Kullenberg et al.Reference Kullenberg, Ysberg and Heilman 13 found lower pain scores with nerve blocks “after treatment,” but did not specify the time at which pain scores were collected. Graham et al.Reference Graham, Baird and McGuffie 12 was the only study that found no benefit to the nerve block.

Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block: Foss et al.Reference Foss, Kristensen and Bundgaard 14 found that although the absolute pain scores were not different between the FICB and the intramuscular (IM) morphine groups, the relative change in pain score was superior at all time points for the FICB group, because the patients in the FICB group had significantly more baseline pain. Monzón et al.Reference Monzón, Vazquez and Jauregui 16 found the FICB offered better pain relief than intravenous (IV) NSAIDs at 15 minutes (p<0.001), but the opposite was true after eight hours. Fujihara et al.Reference Fujihara, Fukunishi and Nishio 15 found improved pain with the FICB at all times compared to rectally administered NSAIDs, but this study was at particularly high risk of bias.

For the secondary outcome of a reduction in IV opiate use, five out of six studiesReference Haddad and Williams 8 - Reference Fletcher, Rigby and Heyes 11 , Reference Foss, Kristensen and Bundgaard 14 using parenteral opiates for standard pain management demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in consumption of opiates with a regional block (Table 2). The study by Kullenberg et al.Reference Kullenberg, Ysberg and Heilman 13 also used opiates for analgesia, but was not included in the secondary outcome analysis, because it was not possible to quantify how much opiates the patients in each group received. Only the study by Graham et al.Reference Graham, Baird and McGuffie 12 failed to demonstrate a significant difference in opiate usage between the 3-in-1 FNB and IV morphine group. In a post-hoc sensitivity analysis where only the double blinded studies were considered, the patients in the nerve block arm required no breakthrough morphine in the study by Foss et al.,Reference Foss, Kristensen and Bundgaard 14 and required significantly less breakthrough morphine in the study by Beaudoin et al.Reference Beaudoin, Haran and Liebmann 10

Table 2 Summary of opiate consumption between regional block and standard pain management groups between studies

Opiate consumption given as a mean where applicable, except in the case of the study by Beaudoin et al., which reported results as a median.

* In Haddad et al.Reference Haddad and Williams 8 there were also four patients in each group given oral doses of dihydrocodeine.

** In Graham et al.,Reference Graham, Baird and McGuffie 12 a “dose” was 0.1 mg/kg of IV morphine.

The reporting of complications was highly variable in the different studies, making it difficult to draw any firm conclusions regarding this outcome. Two studiesReference Murgue, Ehret and Massacrier-Imbert 9 , Reference Fujihara, Fukunishi and Nishio 15 did not attempt to collect complications at all, and five studiesReference Haddad and Williams 8 , Reference Graham, Baird and McGuffie 12 - Reference Foss, Kristensen and Bundgaard 14 , Reference Monzón, Vazquez and Jauregui 16 reported complications, but had significant problems in their methodology, including insufficient length of follow-up, a lack of predefined complications of interest, or absent description of how complications were monitored for and recorded. Only two studiesReference Beaudoin, Haran and Liebmann 10 , Reference Fletcher, Rigby and Heyes 11 had adequate methodology and description of how complications were recorded. Therefore, we felt any aggregate data on the incidence of nausea/vomiting, respiratory depression, delirium, or nerve injury were likely invalid due to the risk of under-reporting of complications. However, it is worthwhile to note that no study reported any immediate life-threatening complications due to the nerve block, including cardiovascular collapse or local anesthetic toxicity.

The a priori planned subgroup analysis was not performed because only one study used ultrasound guidance.Reference Beaudoin, Haran and Liebmann 10

Discussion

This systematic review found that regional nerve blocks are likely at least as effective and possibly superior at reducing pain after a hip or femoral neck fracture compared to standard pain management. Many of the studies found the regional nerve block was significantly more effective at different time points, but there was little consistency between studies. This review found convincing evidence that regional nerve blocks decrease the reliance on opiate medications for pain control after hip or femoral neck fractures, by showing a significant decrease in opiate usage in five out of six studies that used opiates as a control.Reference Haddad and Williams 8 - Reference Fletcher, Rigby and Heyes 11 , Reference Foss, Kristensen and Bundgaard 14 This effect was maintained even in the only two studies which were double blinded,Reference Beaudoin, Haran and Liebmann 10 , Reference Foss, Kristensen and Bundgaard 14 which adds strength to the level of evidence that regional blocks reduce the reliance on IV opiates.

We were unable to draw conclusions regarding whether the reduction in the use of IV opiates led to a reduction in complications, due to under-reporting of complications in the majority of studies. None of the studies reported any immediate life-threatening complications of nerve blocks, and it is unlikely that a significant intravascular injection or local anesthetic toxicity would be missed, due to the rapid cardiovascular collapse, hypotension, arrhythmias, and seizures associated with these complications. However, the total number of patients in this review was small (40 received FNB, 97 received 3-in-1 FNB, 147 received FICB), and therefore the incidence of these rare, but serious complications should not be estimated from this review.

This is the largest systematic review of regional nerve blocks for hip and femoral neck fractures targeted to emergency medicine providers. There have been two prior systematic reviews by Parker et al.Reference Parker, Griffiths and Appadu 17 and Abou-Setta et al.Reference Abou-Setta, Beaupre and Rashiq 18 , which more broadly looked at regional anesthesia for hip and femoral neck fractures in a variety of settings. These prior reviews were not specifically focused on the use of regional nerve blocks in a way that is applicable to emergency medicine providers, because they included the use of continuous femoral nerve block infusion catheters and post-operative patients. Our review also includes a number of studies that were not included in these prior reviews.Reference Beaudoin, Haran and Liebmann 10 , Reference Graham, Baird and McGuffie 12 , Reference Kullenberg, Ysberg and Heilman 13 , Reference Fujihara, Fukunishi and Nishio 15 , Reference Monzón, Vazquez and Jauregui 16 However, both of these reviews reached similar conclusions to our own systematic review, finding that regional nerve blocks led to a significant reduction in pain levels with a reduction in systemic analgesia requirements. The main finding our study adds is that this benefit is directly applicable to patients in the ED, as soon as they arrive in hospital.

Delirium is a well known predictor of impaired functional recovery, quality of life, and increased length of hospital stay after a hip fracture.Reference Marcantonio, Flacker and Michaels 19 We had hoped to show a reduction in delirium with the early administration of regional nerve blocks; however, we found the evidence to be lacking in the studies included in our review. The systematic review by Abou-Setta et al.Reference Abou-Setta, Beaupre and Rashiq 18 performed a meta-analysis on the incidence of delirium with regional nerve blocks versus standard pain management and found moderate-quality evidence that regional nerve blocks led to a statistically significant reduction in delirium (OR 0.33, 95% CI, 0.16-0.66). This is further supported by a controlled trial by Mouzopoulos et al.,Reference Mouzopoulos, Vasiliadis and Lasanianos 20 that found a 13.0% absolute risk reduction for delirium when patients received a daily FICB instead of IM opiates. These studies suggest there may be a benefit towards a reduction of delirium from using regional nerve blocks for patients with hip and femoral neck fractures, but larger studies are needed from the ED setting to show improved patient-oriented outcomes of better recovery and reduced length of stay.

We had initially hoped to perform an a priori subgroup analysis to show whether the use of ultrasound improved the efficacy of regional blocks. We found only one studyReference Beaudoin, Haran and Liebmann 10 using ultrasound guidance for the regional nerve block, and so this subgroup analysis was not performed. However, there are several randomized trials suggesting that ultrasound guidance is superior to landmark or nerve stimulator guidance for the FNB and the FICB. Marhofer et al. performed two randomized controlled trials comparing ultrasound and nerve stimulator guidance for the 3-in-1 FNB and found that ultrasound significantly reduced the onset time, improved the quality of the sensory block, reduced the risk of vascular puncture, and reduced the volume of local anesthetic required to perform the 3-in-1 FNB.Reference Marhofer, Schrögendorfer and Koinig 21 , Reference Marhofer, Schrögendorfer and Wallner 22 Dolan et al. performed an unblinded randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of the FICB with landmark versus ultrasound guidance and found sensory blockade of the anterior, lateral, and medial thigh increased from 47% to 82% with the use of ultrasound guidance.Reference Dolan, Williams and Murney 23 We believe that with the increasing availability of portable ultrasound units in EDs, and evidence suggesting the superiority of ultrasound over landmark and nerve stimulator needle guidance, that ultrasound guidance should be used for needle localization in future studies.

Limitations

Limitations of this systematic review include the risk of publication bias due to the likelihood that smaller, negative studies may have gone unpublished. This review is also limited by the quality of the evidence, which was mostly at a moderate to high risk of bias. The studies also suffered from clinical heterogeneity by using different local anesthetics, opiates, acetaminophen, or even NSAIDs as standard pain control, which also needs to be considered when comparing the studies directly.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this systematic review suggests that regional nerve blocks may be superior to traditional analgesia for patients with hip and femoral neck fractures, and lead to a reduction in IV opiate usage. The performance of regional nerve blocks for hip and femoral neck fractures in the ED can be recommended despite the absence of a large, high-quality randomized controlled trial. There is still a need for further randomized controlled trials to determine the length and magnitude of treatment effect, cost and time effectiveness, and risk of complications. Ideally, future randomized controlled trials will be larger, use standardized reporting methods, will be double blinded or have blinded outcome assessment, and will have a structured system to assess the incidence of complications.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Alexandra Davis, BA, MLIS for developing the search strategy, and to Dr. Lauren Lacroix for translation of the article by Murgue et al.Reference Murgue, Ehret and Massacrier-Imbert 9 Thank you to Dr. A. Fletcher, Dr. D.G. Monzón, and Dr. C. Graham for answering our emails and questions about their studies.

Competing Interests: This study was financially supported by an internal grant from the Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

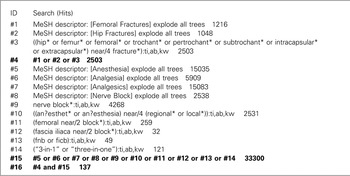

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A: Search strategy for MEDLINE database from 1946 to January 17th, 2014

-

1 Analgesia/ or exp Analgesics/ (430402)

-

2 Anesthesia/ or Anesthesia, conduction/ or exp Nerve Block/ or nerve block$.tw. (64211)

-

3 ((an?esthet$ or an?esthesia) adj4 (regional$ or local$)).tw. (39541)

-

4 (femoral adj2 block$).tw. (624)

-

5 (“3-in-1” or “three-in-one”).tw. (602)

-

6 (fascia iliaca adj2 block$).tw. (88)

-

7 (fnb or ficb).tw. (304)

-

8 or/1-7 (516098)

-

9 Femoral Fractures/ or exp Hip Fractures/ (28423)

-

10 ((hip$ or femur$ or femoral$ or trochant$ or pertrochant$ or intertrochant$ or subtrochant$ or intracapsular$ or extracapsular$) adj4 fracture$).tw. (2671

-

11 9 or 10 (36360)

-

12 randomized controlled trial.pt. (359557)

-

13 controlled clinical trial.pt. (86972)

-

14 randomi?ed.ab. (333750)

-

15 placebo.ab. (148422)

-

16 clinical trials as topic.sh. (166454)

-

17 randomly.ab. (203605)

-

18 trial.ti. (119255)

-

19 or/12-18 (888382)

-

20 8 and 11 and 19 (160)

-

21 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (3863204)

-

22 20 not 21 (149)

APPENDIX B: Search strategy for EMBASE database from 1947 to January 17th, 2014

-

1 analgesia/ or exp *analgesic agent/ (376727)

-

2 anesthesia/ (110148)

-

3 exp nerve block/ (28098)

-

4 nerve block$.tw. (10580)

-

5 ((an?esthet$ or an?esthesia) adj4 (regional$ or local$)).tw. (59989)

-

6 (femoral adj2 block$).tw. (1018)

-

7 (“3-in-1” or “three-in-one”).tw. (916)

-

8 (fascia iliaca adj2 block$).tw. (141)

-

9 (fnb or ficb).tw. (508)

-

10 or/1-9 (542023)

-

11 exp hip fracture/ or exp femur fracture/ (46955)

-

12 ((hip$ or femur$ or femoral$ or trochant$ or pertrochant$ or intertrochant$ or subtrochant$ or intracapsular$ or extracapsular$) adj4 fracture$).tw. (38042)

-

13 11 or 12 (54767)

-

14 10 and 13 (1425)

-

15 Clinical trial/ (900277)

-

16 Randomized controlled trial/ (367232)

-

17 Randomization/ (64876)

-

18 Single blind procedure/ (18855)

-

19 Double blind procedure/ (124397)

-

20 Crossover procedure/ (39822)

-

21 Placebo/ (249571)

-

22 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (99324)

-

23 Rct.tw. (13604)

-

24 Random allocation.tw. (1402)

-

25 Randomly allocated.tw. (20617)

-

26 Allocated randomly.tw. (1987)

-

27 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (898)

-

28 Single blind$.tw. (14686)

-

29 Double blind$.tw. (153405)

-

30 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (393)

-

31 Placebo$.tw. (210057)

-

32 Prospective study/ (262206)

-

33 or/15-32 (1438861)

-

34 Case study/ (32765)

-

35 Case report.tw. (285990)

-

36 Abstract report/ or letter/ (918902)

-

37 or/34-36 (1232009)

-

38 33 not 37 (1400557)

-

39 14 and 38 (278)

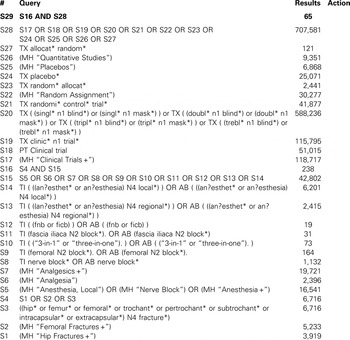

APPENDIX C: Search Strategy for Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

APPENDIX D: Search strategy for CINAHL database