CLINICIAN’S CAPSULE

What is known about the topic?

Delirium is frequent in older inpatients but often goes undetected. A short tool, the 4 A’s Test (4AT), was created and validated for the detection of delirium.

What did this study ask?

This study compared the performance of the French version of the 4AT (4AT-F) with the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) for the screening of delirium.

What did this study find?

The 4AT-F was a fast and reliable screening tool for delirium in the emergency department (ED).

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

Because of its quick administration time, it allows for systematic screening of patients at risk of delirium and cognitive impairment.

INTRODUCTION

Delirium is a severe neuropsychiatric condition that causes serious health consequences such as long-term cognitive and functional decline, increased risk of institutionalization and mortality, and an increased length of hospital stay. All these issues could increase the burdens on our health system with regards to costs, resources utilization, and crowding.Reference Bellelli, Morandi and Davis 1 , Reference Han, Shintani and Eden 2 Older inpatients experience delirium frequently, affecting approximately 20% to 25% of patients aged 65 years and older.Reference Han, Vasilevskis and Shintani 3 , Reference Shenkin, Russ, Ryan and MacLullich 4 Older hospitalized adults are particularly vulnerable, as a prolonged stay in the emergency department (ED) (≥10 hours) has been associated with an increased risk of incident delirium.Reference Bo, Bonetto and Bottignole 5 Our group found similar results in a retrospective cohort study of older adults, with one out of five cases experiencing incident delirium after a 12-hour ED stay.Reference Émond, Grenier and Morin 6 However, many studies have reported that between 50% and 75% of delirium episodes go unnoticed and undiagnosed.Reference Bellelli, Morandi and Davis 1 , Reference O’Regan, Ryan and Boland 7 , Reference Oliver 8 This is worrisome because a quick diagnosis of delirium could promote early management and minimize its various health consequences. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that health care professionals learn to better recognize this condition. In 2014, the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) recommended systematic cognitive screening for older patients treated in the ED. 9

However, the currently available tools to screen or diagnose patients at risk of delirium or cognitive impairment are time-consuming.Reference Bellelli, Morandi and Davis 1 , Reference O’Regan, Ryan and Boland 7 For example, the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM),Reference Inouye, van Dyck and Alessi 10 , Reference Monette, Fort and Fung 11 which is the gold standard screening test for delirium (sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 100%), involves a semi-structured interview of approximately 20 minutes that would be impossible to systematically perform in the fast-paced ED environment. Another widely used tool to screen for cognitive impairment is the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-m) (sensitivity of 73% and specificity of 67%), which takes approximately 10 minutes to administer.Reference Knopman, Roberts and Geda 12 Therefore, more adapted tools are needed to comply with the SAEM guidelines. In light of this, a shorter tool, the 4 A’s Test (4AT), was created and validated for the detection of cognitive impairment and delirium. The 4AT is simple and can be used with patients experiencing visual and hearing problems without requiring a physical response. The test does not require specific training and only takes two minutes to administer. The 4AT can also perform as a general cognitive screening tool, thus avoiding the need for separate tools for delirium and other cognitive impairments,Reference Bellelli, Morandi and Davis 1 because of its different cut-offs aiming to differentiate cognitive impairment and delirium.Reference Lees, Corbet and Johnston 13 To make sure that each patient can be screened without a significant increase in workload for ED health professionals, it appears necessary to validate this brief screening tool in different contexts.

Building on the positive results of the English version of the 4AT,Reference Han, Shintani and Eden 2 , Reference de Jager, Budge and Clarke 14 , Reference Charlson, Pompei, Ales and MacKenzie 16 the purpose of the present study was to evaluate the performance of the French version of the 4AT (4AT-F) for the detection of delirium and cognitive impairment in ED patients aged 65 years and older, in comparison with the CAM and the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS)s.Reference de Jager, Budge and Clarke 14

METHOD

Setting

This was a prospective study conducted in four Canadian EDs: the CHU de Quebec–Hôpital de l’Enfant-Jésus (Quebec City), the CHU de Quebec–CHUL (Quebec City), the Hôpital de Trois-Rivières (Trois-Rivières), and the Centre Hospitalier de Lanaudière (Lanaudière). Data collection was performed by trained research assistants over a period of six to eight weeks at each participating centre (between February and May 2016).

Participants

This study included patients aged 65 years and older who were independent or semi-independent (able to perform at least five activities of daily living), had an eight-hour exposure to the ED environment from the time of registration (because of the high frequency of delirium with prolonged periods of stay in the ED), and were admitted (or waiting to be admitted) to a hospital ward. Patients were excluded if they lived in a nursing home or long-term care facility, had an unstable medical state that could lead to intensive care, could not communicate in French, or were unable to provide consent. Finally, patients with a history of a psychiatric disorder were also excluded.

Assessments and procedure

Trained research assistants screened patients after their eight-hour exposure to the ED environment to determine eligibility. After appropriate consent was obtained, data from participant medical records and sociodemographic information were collected. Functional status was assessed using the Older Americans Resources and Services (OARS) Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire, a widely used and well-validated tool.Reference McCusker, Bellavance, Cardin and Belzile 15 The Charlson Comorbidity Index, which indicates the burden of disease and risk of mortality after one year, was also calculated from patient medical records.Reference Charlson, Pompei, Ales and MacKenzie 16 An Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) score, a severity of disease classification system, was also calculated from the patient medical records.Reference Knaus, Draper, Wagner and Zimmerman 17 Baseline cognitive status was assessed using the TICS-m (adjusted for level of education, with a cut-off of 27). Patients were screened for delirium using the CAM, a tool assessing the presence of an acute onset and fluctuating change and inattention, disorganized thinking, and/or an altered level of consciousness. Because of the fluctuating course of delirium, participants were then administered the CAM and 4AT-F twice a day (morning and evening) throughout their stay in the ED and up to 24 hours after being admitted to a hospital ward. A prevalent delirium means that the patient was delirious at the initial interview, and an incident delirium means that the patient became delirious during the stay (in the ED or after admission).

Each team of research assistants received standardized training by an experienced member of the mentoring team of the Hôpital de l’Enfant-Jésus, who also specializes in the administration of the CAM. They also attended a group training session conducted by the study coordinator and an experienced research nurse and underwent five-hour personalized field training. They were also provided with a detailed training manual.

The 4AT-F

The 4AT-F was translated from the English version of the 4AT and then validated by two health care professionals experienced in cognitive impairment and delirium. As shown in Appendix 1, the first element assessed by the 4AT-F is a patient’s awareness (normal, mild sleepiness, or clearly abnormal). The second item evaluates spatial and temporal orientation, and the questions asked are from the Abbreviated Mental Test-4 (AMT-4) (do the patients know their age, their date of birth, their current location, and the current year?).Reference Bellelli, Morandi and Davis 1 The third component evaluates a patient’s level of attention (i.e., participants are asked to recite the months of the year backwards that is also a short test in itself).Reference O’Regan, Ryan and Boland 7 Finally, the last item evaluates an acute change or a fluctuating course of cognition, awareness, or any other mental function within the last two weeks that would still be apparent in the last 24 hours. The total score of the 4AT-F varies between 0 and 12. A score of zero suggests a normal cognitive status, a score between one and three suggests the possibility of a severe to moderate cognitive impairment, and a score of four and more suggests the possibility of a delirium, with or without cognitive impairment.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Means and frequency tables were used to describe the study sample as appropriate. We evaluated the adequacy of the 4AT-F to screen for delirium and cognitive impairment in terms of its sensitivity and specificity that were estimated for two outcomes at the initial interview: cognitive disorders as measured by the TICS-m, and delirium as defined by the CAM. Exact binomial confidence intervals were obtained for these quantities. The 4AT-F and CAM evaluations were also performed twice daily during the hospital stay. Prediction performance statistics and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the 4AT-F to predict the CAM in this repeated measures design were estimated using log-binomial generalized estimating equations models,Reference Genders, Spronk and Stijnen 18 one for each characteristic, with a single random effect for subjects and a compound symmetry working correlation.

RESULTS

Sample description

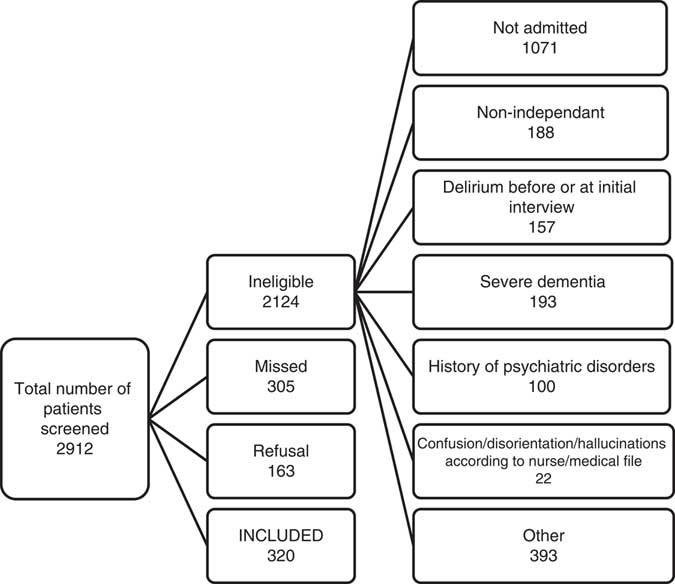

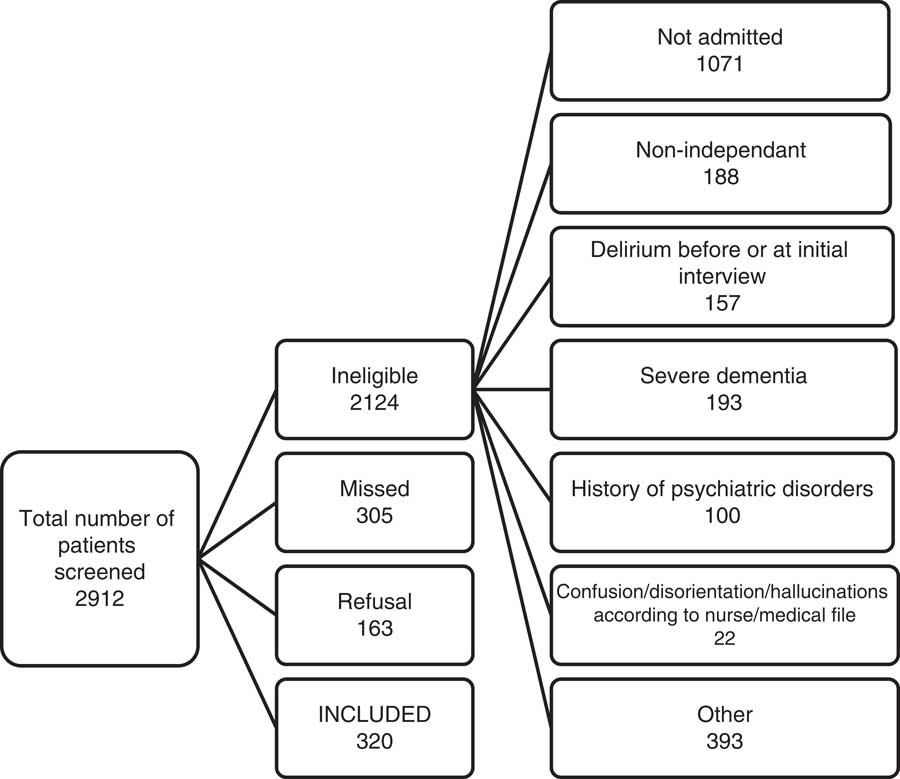

A total of 2,912 patients were screened in the study across our four sites. Of those, 2,124 were excluded, 305 were missed, and 163 refused to participate, leaving us with a cohort of 320 patients (Figure 1). As shown in Table 1, within the cohort, 168 were women (52.3%). The mean age of our participants was 76.8 years; the mean Charlson score was 1.8; and the mean APACHE score was 12.2.

Figure 1 Flowchart of study participants.

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of the study population

APACHE II = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; ED = emergency department; OARS = Older Americans’ Resources and Services; TICS-m = modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status.

Prevalence and incidence of delirium, prevalence of cognitive impairment, and classification performance of the 4AT-F

As shown in Table 2, among the recruited participants, 21 (7%) had a positive CAM at the initial interview, and 28 (10%) had an incident delirium according to a subsequent CAM, for a total of 49 patients with at least one positive CAM during their ED or hospital stay. According to the 4AT-F, 80 participants (25%) had a possible prevalent delirium, and 72 had an incident delirium, for a total of 152 delirious patients (Table 2). Of note, patients with prevalent delirium were excluded from the calculation of incident delirium. Regarding classification performance, our results show that the 4AT-F has a sensitivity of 84% (95% CI 76–93) and specificity of 74% (95% CI 70–78) for the detection of delirium, with a positive predictive value of 19% (95% CI 14–25) and negative predictive value of 98% (95% CI 98–99). A positive likelihood ratio of 3.23 and negative likelihood ratio of 0.22 were obtained (Table 2).

Table 2 Prevalent and incident delirium combined according to the CAM and 4AT-F

4AT-F = 4 A’s Test in French; CAM = Confusion Assessment Method; CI = confidence interval.

* Missing data removed.

As shown in Table 3, according to the TICS-m, 45 (14%) patients had cognitive impairment at the initial interview, and the 4AT-F detected 46 (14%) patients who had cognitive impairment at baseline. Regarding classification performance, the 4AT-F showed a sensitivity of 49% (95% CI 34–64) and specificity of 87% (95% CI 82–92). A positive predictive value of 48% (95% CI 33–63) and negative predictive value of 88% (95% CI 83–92) were obtained. The 4AT-F showed a positive likelihood ratio of 3.77 and negative likelihood ratio of 0.59 for the detection of cognitive impairment (Table 3).

Table 3 Cognitive impairment at the initial interview according to TICS and the 4AT-F

4AT-F = 4 A’s Test in French.

* Missing data and delirium cases were removed.

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests a good performance for the 4AT-F as a screening tool for incident delirium in the ED. Our results showed that the 4AT-F has a sensitivity of 84%, specificity of 74%, and negative predictive value of 98% for delirium, making it a useful detection tool among older ED patients. Our positive predictive value of 19% suggests that the test was positive for some non-delirious patients. However, this would avoid the danger of missed cases that could be a positive issue in the ED context. As the 4AT-F is a screening tool, further testing is required to confirm a diagnosis in a patient who had a positive result. Therefore, a proposed screening tool is a rapid test with good sensitivity. Its use in the ED would allow systematic screening of patients at risk of delirium, without significantly increasing the workload of the ED staff, and could eventually minimize the possible consequences of delirium.

The English version of the 4AT has been validated and is part of international clinical practice. 19 According to Lees et al., the 4AT has favourable properties to screen for delirium, using the CAM as the gold standard, and reasonable properties for the screening of cognitive impairment, as compared with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).Reference Lees, Corbet and Johnston 13 Bellelli et al. also found that the 4AT is a valid method with high sensitivity and specificity to screen for delirium in older patients who are admitted to a geriatric ward,Reference Bellelli, Morandi and Davis 1 as compared with a delirium diagnosis provided by a blinded geriatrician. A Thai version of the 4AT was also validated for patients admitted to general medical wards and obtained satisfactory sensitivity and specificity for delirium, as compared with diagnoses made by a psychiatrist using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV-TR) 20 and the six-item Thai Delirium Rating Scale.Reference Kuladee and Prachason 21 Despite minor differences, our results seem consistent with the existing literature. While the sensitivity obtained in the present study (84%) for the detection of delirium was similar to that obtained by Bellelli (89%) and Kuladee (83%), our specificity (74%) was lower than theirs (84% and 86%, respectively).Reference Bellelli, Morandi and Davis 1 , Reference Kuladee and Prachason 21 These small differences could be explained by the reference standard choice. Indeed, Bellelli used a geriatrician’s diagnosis based on the DSM criteria for deliriumReference Bellelli, Morandi and Davis 1 and Kuladee used the six-item Thai Delirium Rating Scale (sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 86%),Reference Kuladee and Prachason 21 and we used the CAM. Our population was also a little different than Bellelli’s: our patients were younger (mean age of 76.8 years) than theirs (mean age of 83.9 years)Reference Bellelli, Morandi and Davis 1 and recruited in an ED, and Bellelli’s cohort was recruited in a geriatric ward and rehabilitation department for post-acute and chronic disability. Our participants were similar to those of the Kuladee study.

Our sensitivity and specificity results were lower than those obtained by Lees et al. (sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 82%).Reference Lees, Corbet and Johnston 13 This difference could be explained by the fact that our study was conducted in an ED, and theirs was conducted in an acute stroke unit.Reference Lees, Corbet and Johnston 13 Our sensitivity result for cognitive impairment (49%) was much lower than that of Lees (86%), but our specificity (87%) was better than theirs (78%). This could be explained by the use of different reference tools; the Lees’ study used the MoCA,Reference Lees, Corbet and Johnston 13 and we used the TICS-m. The major difference between these two tools resides in the fact that the MoCA provides a more detailed picture of a patient’s executive functions, memory, and language than the TICS.Reference Vogel, Banks, Cummings and Miller 22 In addition, even though the mean age of our populations was similar (76.8 years old in our study versus 74), some differences should be noted, namely the fact that our study included patients with any medical condition, and the Lees’ study included stroke survivors only.Reference Lees, Corbet and Johnston 13

More recently, a study by O’Sullivan examined the classification performance of the 4AT in ED patients and obtained a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 91% for the screening of delirium.Reference O’Sullivan, Brady and Manning 23 Those results are globally consistent with ours (sensitivity and specificity of 84% and 74%, respectively), despite a difference that could be related to the gold standard used (we used the CAM, and O’Sullivan used the blinded diagnosis provided by a geriatrician and the Delirium Rating Scale-Revised-98 [DRS-R98], a validated assessment tool). For the screening of cognitive impairment, the study obtained a sensitivity of 84% and specificity of 63%.Reference O’Sullivan, Brady and Manning 23 Those results suggest a better sensitivity for the 4AT to screen for cognitive impairment than the value we obtained (sensitivity of 49%), possibly due to the fact that we had fewer patients with dementia in our population. However, our specificity was better than theirs, suggesting fewer false positive cases of cognitive impairment.

Despite the reliability and efficacy of the 4AT-F, other brief screening tools are gaining popularity. For example, the brief CAM (bCAM) and CAM for Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU), which have both been validated for delirium screening in older ED patients.Reference Han, Wilson and Graves 24 , Reference Han, Wilson and Vasilevskis 25 If performed by a research assistant, the bCAM has a sensitivity of 84% (95% CI 72–92) and specificity of 78% (95% CI 72–92)Reference Han, Wilson and Vasilevskis 25 that are similar to those of the 4AT-F. However, no French version of the bCAM has yet been validated. The CAM-ICU has a sensitivity of 68% (95% CI 54–79) and specificity of 99% (95% CI 97–99).Reference Han, Wilson and Graves 24 This specificity is higher than that of the 4AT-F, but in a screening context, sensitivity is more important than specificity. More importantly, the bCAM and CAM-ICU do not allow for the simultaneous screening of delirium and cognitive impairment, as opposed to the 4AT-F. Further, no French version of the bCAM or CAM-ICU has yet been validated. Another derivation of the CAM, the 3D-CAM, is also gaining popularity. This test has one of the best diagnostic accuracies, with a sensitivity of 95% (95% CI 84–99) and specificity of 94% (95% CI 90–97).Reference Marcantonio, Ngo and O’Connor 26 However, its administration time is higher than that of the other tests, making it less likely to be used in the ED context.

A strength of this study is the comparison of the 4AT-F with the CAM, which is an effective and well-validated tool to screen for delirium.Reference Inouye, van Dyck and Alessi 10 , Reference Monette, Fort and Fung 11 Furthermore, the fact that our study was conducted in four different EDs and three different geographical regions of our province increases the external validity of our study. Moreover, the 4AT-F was administered by trained research assistants, not by experienced physicians, demonstrating that it could be administrated by any health care professional with varying levels of seniority, even though more research is needed to confirm this point.

LIMITATIONS

Some limitations of the study must be acknowledged. First, the prevalence and incidence of delirium were low. This could have had an impact on the precision of our estimates of the positive and negative predictive values. Second, our participants may not be perfectly representative of an ED population, as our inclusion and exclusion criteria eliminated any non-independent or severely ill patients. This could have decreased the generalisability of our results and might also explain our low rate of delirium. Third, the test we used to compare the ability of the 4AT-F to screen for cognitive impairment (the TICS-m) may not be the most efficient. Fourth, the 4AT-F and CAM were administered at the same moment by the same research assistant. This might have introduced bias that was only partially considered in our statistical model.

Clinical implications

The clinicians could use the 4AT-F in the ED as a screening test for each patient at risk of delirium and, according to the result of the test, could decide to perform a more complete evaluation. This would allow for screening for patients who have delirium without increasing the workload of ED staff. Indeed, the 4AT-F remains a screening test, not a diagnostic test. A more detailed cognitive evaluation may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.Reference Voyer, Champoux and Desrosiers 27 The 4AT-F could also be used to screen for cognitive impairment, although confirmatory tests are required.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this study suggests that the 4AT-F would be a quick, efficient, and useful screening tool for delirium and possibly for cognitive impairment in older francophone patients in the ED. Further study will be needed to evaluate the efficiency of its implementation in the ED and its use in a less independent and sicker population or even in discharged patients.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank all the research assistants who participated in patient recruitment.

Competing interests: This study was funded by <Blinded>. None declared.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit erial for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2018.367