CLINICIAN'S CAPSULE

What is known about this topic?

Health disparities between racial and ethnic groups are well documented, and there is evidence these disparities exist in ED care.

What did this study ask?

What is known about the ways ethnicity and/or race impact processes of ED care?

What did this study find?

There is evidence of disparities in waiting times, triage, analgesia, diagnostics, treatment, and patient experiences between racial/ethnic groups.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

This review allows clinicians to reflect on their practice and facilitates the design of studies and interventions to address disparities.

INTRODUCTION

Disparities in health care between racial and ethnic minority groups compared with whites have been well documented in Canada and the United States.1–Reference Smedley, Stith and Nelson3 In the United States, disparities in cardiac revascularization and anti-retroviral therapy have been shown to result in higher morbidity and mortality independent of access to care.3 In Canada, First Nations people report avoiding care based on experiences of racism.2 Racial and ethnic disparities exist when adjusting for socioeconomic status, gender, and other health care related factors.3

Disparities have also been documented in emergency care between socioeconomic groups for likelihood of receiving CT scans,Reference Bhayana, Vermeulen, Li, Hellings, Berdahl and Schull4 between genders for opioid prescription,Reference Chen5 and between races for analgesia in fractures.Reference Todd, Samaroo and Hoffman6,Reference Todd, Deaton, D'Adamo and Goe7 Such disparities are associated with poorer health outcomes; thus, it is important to identify how race and ethnicity affect emergency care.Reference Smedley, Stith and Nelson3 The objective of this article is to provide an overview of the literature on how patient ethnicity and race impact processes of emergency department (ED) care. This review will be of use to scholars designing studies on disparities in care or developing interventions to address disparities.

METHODS

In this scoping review, we synthesize a diverse body of literature to uncover what has been studied related to this topic, how disparities have been explained, and which causes of disparities should be studied further.Reference Arksey and O'Malley8,Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien9 Arksey and O'Malley describe scoping reviews as a methodology that develops an understanding of the breadth and nature of research surrounding a topic.Reference Arksey and O'Malley8 Their framework consists of: (1) research question identification, (2) identification of relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting data, and (5) collecting, summarizing, and reporting results.Reference Arksey and O'Malley8 For steps 4 and 5, we incorporate the suggestion by Levac et al. to adopt qualitative thematic analysis to organize and understand data.Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien9

Identification of the research question

This review is guided by the question: What is known about how ethnicity and/or race impact processes of ED care? Our question is deliberately broad to avoid excluding relevant studies before gaining an understanding of the literature.Reference Arksey and O'Malley8

Identification of studies

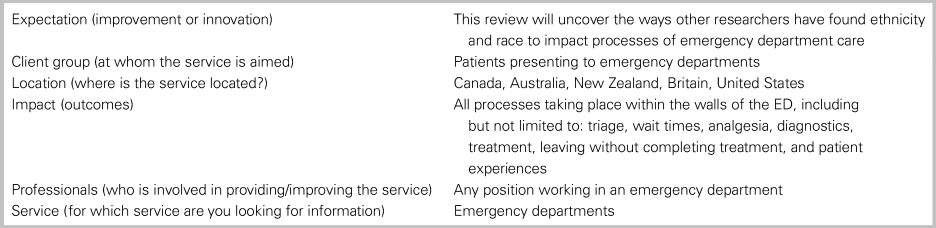

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were created using the “ECLIPSE” model for structuring search strategies for nonclinical, health care related queries.Reference Wildridge and Bell10 See Table 1. We used the model by Asplin et al. of ED crowding to identify processes common to emergency care.Reference Asplin, Magid, Rhodes, Solberg, Lurie and Camargo11 This model conceptualizes three categories of ED processes: input, throughput, and output. We consider throughput processes, which we consider to include everything taking place within the ED. As Asplin et al. note the importance of barriers to care experienced by vulnerable populations, we have included studies on patient experiences.Reference Asplin, Magid, Rhodes, Solberg, Lurie and Camargo11

Table 1. ECLIPSE Model inclusion criteria

Literature from the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Britain was included. These countries represent Britain and its former colonies, with similar emergency care systems and contemporary white Anglophone majorities. We expected cultural similarities between majority groups in each country to lead to comparable interactions between minority and majority groups. We used Stone and Piya's definition of ethnic groups as “functional units of social organization which consist of members who define themselves, or are defined, by a sense of common historical origins that may also include religious beliefs, a similar language, or a shared culture.”Reference Stone and Piya12 We defined race broadly as a socially organized “system of categorization” based on “real or imagined” physical differences/phenotypes.Reference Lemonik-Arthur13 No time limits were used, and only full-text, English studies were included.

Data sources, search terms, and strategy

A University of Alberta librarian was consulted for database selection and search strategy development. Searches were performed in 2018 in MEDLINE/PubMed (biomedical sciences, 1946–present), EMBASE, CINAHL Plus, Social Sciences Citation Index, SCOPUS, and JSTOR. Five journals were hand searched; The Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, Academic Emergency Medicine, Emergency Medicine Australasia, Emergency Medicine Journal, and Annals of Emergency Medicine. We developed key terms for racial and ethnic groups by identifying populous minority groups in each country. We then trialed additional terms appearing in initial searches to identify whether inclusion of these terms returned additional results, in keeping with Arksey and O'Malley's recommendation that search strategy be iteratively revised as familiarity with literature develops.Reference Arksey and O'Malley8 Final search query protocol is detailed in the Supplemental Online Appendix A.

Study selection

Initial screening of titles and abstracts was performed using predetermined inclusion criteria. To refine criteria and ensure that captured articles addressed our research question, the first 100 citations from MEDLINE were screened by two reviewers (A.O., P.M.).Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien9 All remaining citations were screened by one reviewer (A.O.). Articles included after title and abstract screening were obtained for full-text screening, completed by one reviewer (A.O.).

Charting of data and summarization of results

A data extraction form was developed as authors gained familiarity with the literature.Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien9 Data extracted included ED process(es) studied, racial/ethnic groups, country, design, year published, control variables, findings, author-proposed explanation of findings, and limitations. Data were compiled into Microsoft Excel for synthesis by one author (AO). Two authors (A.O., P.M.) met throughout extraction to review data and analyze author-proposed causes of disparities thematically. As themes were identified, they were added as fields within the extraction form. Studies were then categorized by ED process studied and cross-tabulated with categories of authors’ explanations of disparities.

RESULTS

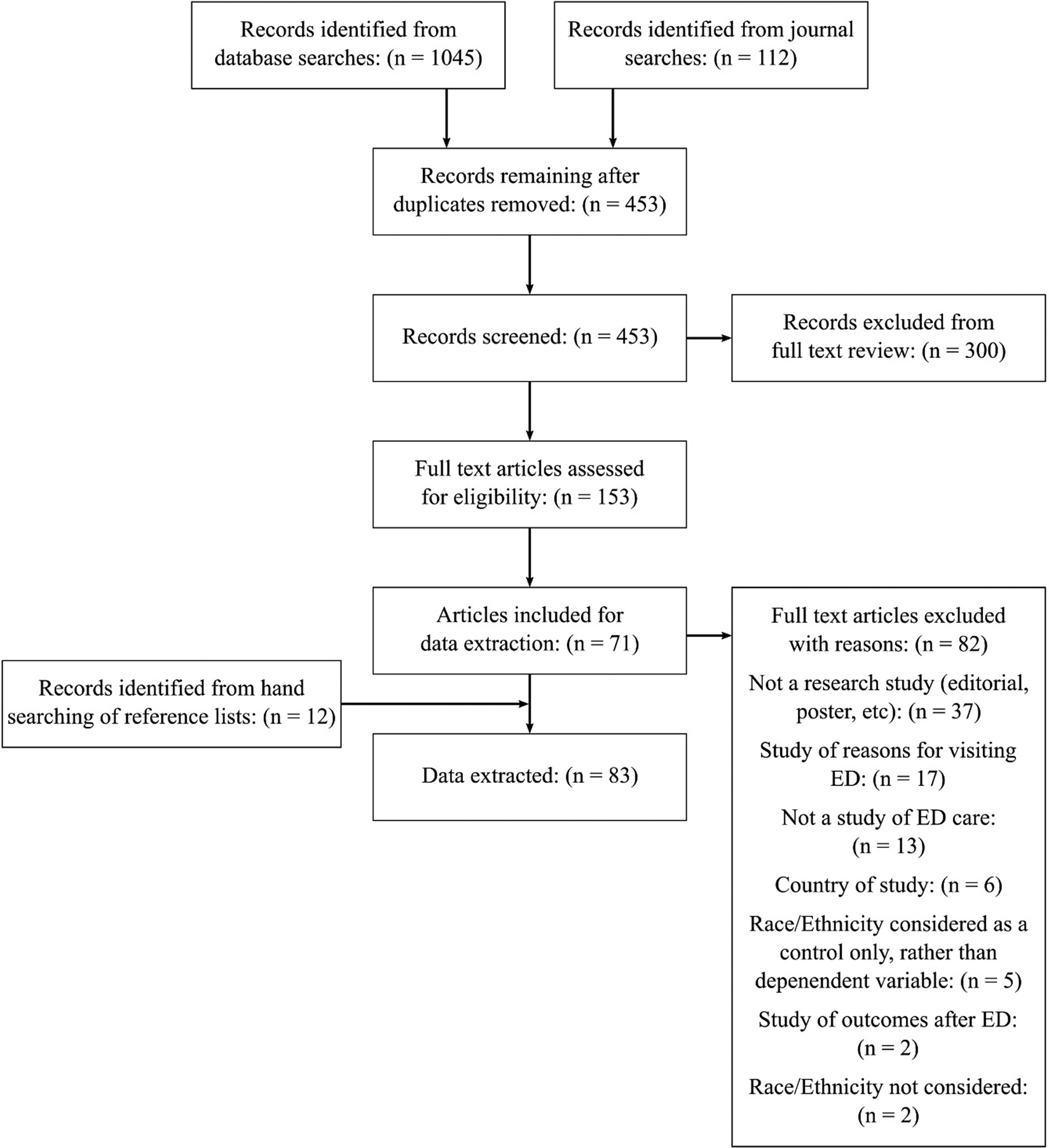

The original search yielded 1,157 citations, reduced to 453 after duplicate removal. Of 100 titles and abstracts screened by two reviewers, reviewers agreed on inclusion of 49/100 and exclusion of 41/100. Following discussion, 55/100 were included, and the remaining 45 excluded. Based on this exercise, inclusion criteria were modified to exclude articles on minority group medical literacy, as we determined this was a patient characteristic rather than an ED process. During full-text screening, citations were excluded if they were not full-text articles, focused on reasons for or rates of visiting EDs, were from an excluded country, considered race/ethnicity as a control variable rather than dependent variable, examined outcomes after leaving ED, or did not consider race/ethnicity. Seventy-one citations were included for data extraction. Reference list searching yielded 12 additional citations. See Figure 1, PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

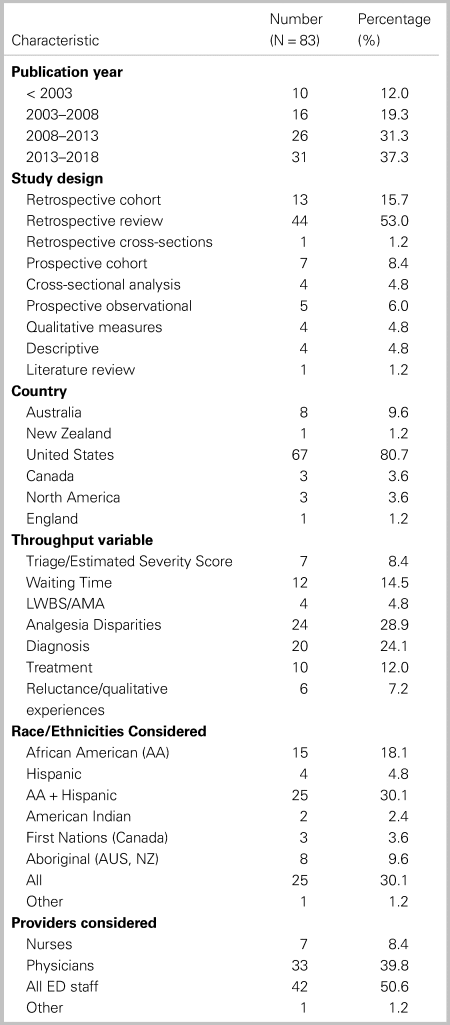

General characteristics of included articles

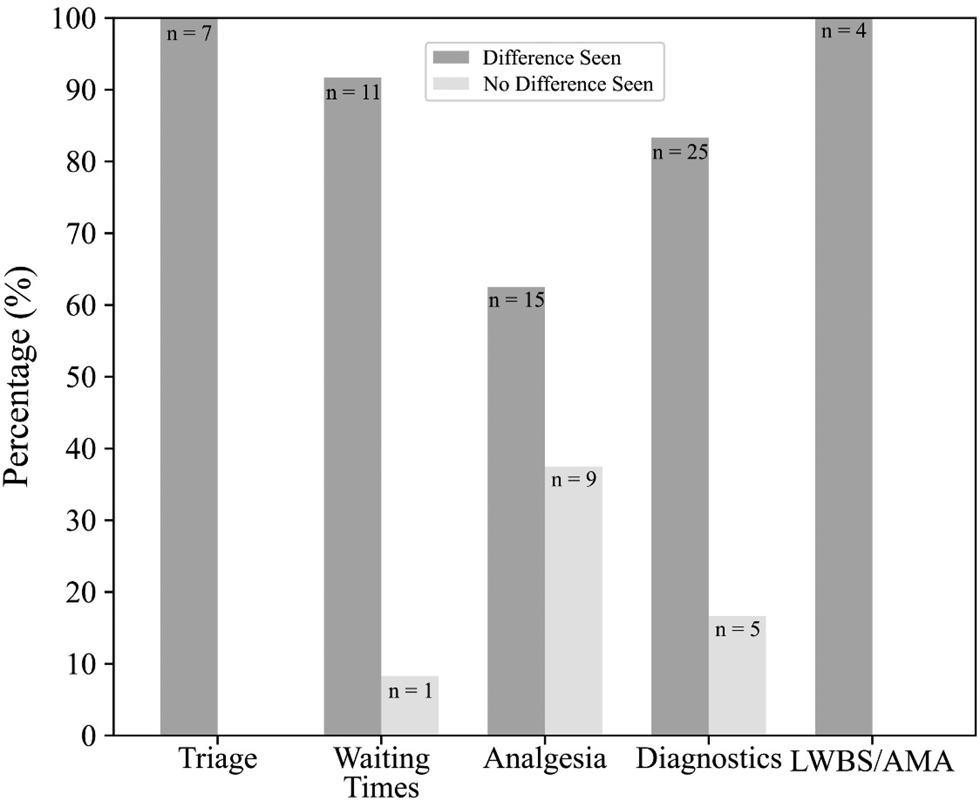

General characteristics of articles are reported in Table 2. Eighty-three articles were published over 28 years, from 1990 to 2018; 68% of studies were published after 2008. Studies are clustered for analysis by ED process (triage, wait times, analgesia, diagnosis, treatment, leaving without being seen (LWBS)/against medical advice (AMA), and patient experiences). Categories are not mutually exclusive, as some studies report on multiple processes. Citations of all included studies, and notes on findings and methodologies are given in the Supplemental Online Appendix B. See Figure 2 for an analysis of outcomes by study category.

Figure 2. Outcomes by study category.

Table 2. General characteristics of included articles

Triage scores

Seven studies (100%) considering triage scores found differences between racial and ethnic minority v. majority groups. Six (86%) of seven found minority groups had less acute scores, while one (14%) found that the minority group had more acute scores.Reference Vigil, Alcock and Coulombe14–Reference Johnston-Leek, Spirvulis, Stella and Palmer16 Some investigators found minority groups had less acute triage scores despite similar presenting complaints or pain ratings.Reference Lopez, Wilper, Cervantes, Betancourt and Green15,Reference Vigil, Coulombe and Alcock17

Waiting times

Twelve studies examined waiting times. Eleven (91%) found that minority groups waited longer on average to be assessed than white patients.Reference Sonnenfeld, Pitts, Schappert and Decker18

Analgesia

Twenty-four studies examined differences in analgesic administration. Fifteen (63%) of 24 found differences in analgesic administration between racial and ethnic groups. Six (35%) of 17 studies found minority group patients were less likely to receive any analgesics compared with the majority group. Eleven (85%) of 13 studies found that racial/ethnic minority groups were less likely to receive opioids. Three (100%) of three studies found that racial/ethnic minority groups were less likely to receive a prescription for analgesics. Two (67%) of three studies found minority groups waited longer for analgesics. Nine (38%) of 24 studies found no differences between racial and ethnic groups for any process studied.

Diagnostic testing and treatment

Thirty studies examined differences in diagnostic testing and treatment between racial/ethnic groups. Differences in administration of diagnostic testing and treatment for chest pain, asthma, psychiatric disorders, gastro-intestinal complaints, trauma, and strokes were investigated. Twenty-five (83%) of 30 found differences between racial/ethnic minority groups on at least one of the evaluated processes.Reference Pezzin, Keyl and Green19–Reference Payne and Puumala21

Studies that found no differences in diagnostics were largely focused on trauma. Five studies examined administration of diagnostic testing in trauma, with four (80%) finding no differences.Reference Shafi and Gentilello22 See Appendix B for details regarding disparities seen in diagnosis and treatment.

LWBS and leaving AMA

Four (100%) studies investigating LWBS/AMA found LWBS/AMA more likely in minority group than majority group patients.Reference Harrison, Finkelstein, Puumala and Payne23,Reference Wright24 All focused on Indigenous populations. Harrison et al. found that minority patients other than Indigenous patients were not more likely than their white counterparts to LWBS after controlling for insurance status.Reference Harrison, Finkelstein, Puumala and Payne23 This finding was recently replicated by Weber et al. 2018, in a study published after our search.Reference Weber, Ziegler, Kharbanda, Payne, Birger and Puumala25

Subjective experiences

Two studies analyzed patient trust in providers. Both found nonwhite patients had lower trust scores for providers than white patients.Reference Fields, Abraham, Gaughan, Haines and Hoehn26,Reference Lee, Tamayo-Sarver, Kinneer and Hobgood27 In qualitative studies of minority patient experiences, themes included discrimination, stereotyping, language barriers, and judgment.Reference Pickner, Ziegler and Hanson28,Reference Chapman, Smith and Martin29

Author explanations of causes of disparities

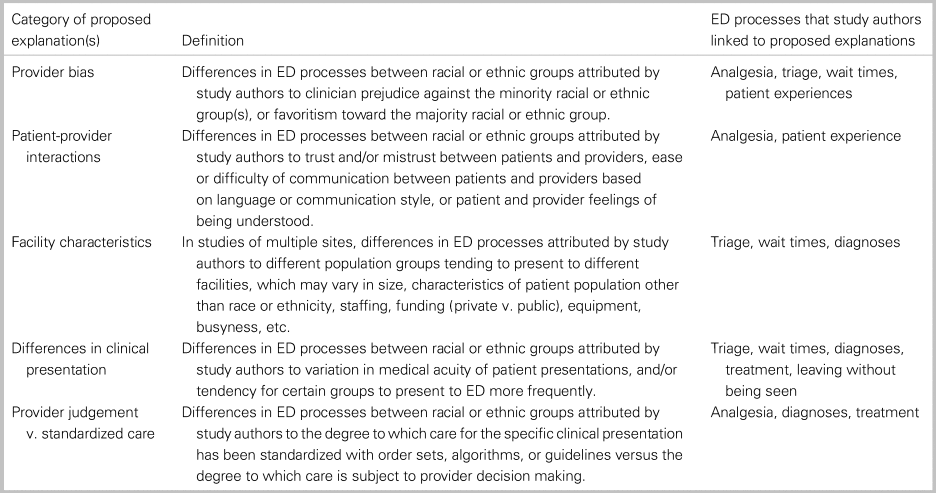

Using inductive thematic analysis, we categorized explanations of disparities that authors of studies proposed. See Table 3 for definitions of categories. Proposed explanations fall into categories of: (1) provider bias, (2) patient-provider interactions, (3) facility characteristics, (4) clinical presentations, and (5) provider judgement v. standardized care. In some cases, these possible causes appear in the discussion sections of articles, and are not investigated. Authors sometimes cite studies to support proposed explanations of disparities, but it is beyond the scope of this review to follow up on the citations authors relied on.

Table 3. Author-proposed explanations of disparities

Provider bias

Provider biases were suggested as a cause of disparities in analgesia provision,Reference Pletcher, Kertesz, Kohn and Gonzales30,Reference Singhal, Tien and Hsia31 triage scores,Reference Vigil, Alcock and Coulombe14,Reference Vigil, Coulombe and Alcock17 wait times,Reference Haywood, Tanabe, Naik, Beach and Lanzkron32,Reference James, Bourgeois and Shannon33 and patient experiencesReference Pickner, Ziegler and Hanson28 in article discussion sections. These author-proposed explanations are based in discussion and do not have supporting data. One study asserted the possibility of overt discrimination as a cause for wait time differences.Reference James, Bourgeois and Shannon33 Authors finding differences in opioid prescribing suggested that physicians may be more worried about opioid abuse and diversion in certain racial/ethnic groups.Reference Singhal, Tien and Hsia31,Reference Joynt, Train, Robbins, Halterman, Caiola and Fortuna34

Patient-provider interactions

Patient-provider interactions were posited to impact analgesia provision,Reference Pletcher, Kertesz, Kohn and Gonzales30,Reference Ortega, Velden, Lin and Reid35 diagnostics,Reference Levas, Dayan and Mittal20 and patient experiences.Reference Fields, Abraham, Gaughan, Haines and Hoehn26,Reference Pickner, Ziegler and Hanson28 Authors proposed that trust for providers may be affected by language barriers, as language differences between providers and patients make it difficult for the patient to articulate their concerns.Reference Fields, Abraham, Gaughan, Haines and Hoehn26,Reference Lee, Tamayo-Sarver, Kinneer and Hobgood27 Another proposed explanation for disparities in trust is a history of discrimination and mistreatment of minority groups.Reference Lee, Tamayo-Sarver, Kinneer and Hobgood27 Authors theorized that patients feel less enabled in decisions about health care when “social distance” is greater between patients and providers.Reference Lee, Tamayo-Sarver, Kinneer and Hobgood27

Facility characteristics

Characteristics of EDs that minority groups present to were theorized to influence differences in triage scoresReference Lopez, Wilper, Cervantes, Betancourt and Green15 and wait times.Reference Sonnenfeld, Pitts, Schappert and Decker18 Hospitals where minority patients present may be more likely to be in urban centers, serve larger populations, have longer wait times, and have higher average acuity.Reference James, Bourgeois and Shannon33 Seven studies examined wait times within hospitals compared with between hospitals by race and ethnicity. Five (71%) of these studies found differences in wait times between races/ethnicities was present both within and between hospitals, suggesting that facility characteristics alone do not explain this disparity.Reference Sonnenfeld, Pitts, Schappert and Decker18

Differences in clinical presentations

Numerous authors mention that differences in clinical presentation may impact care. Lower acuity at presentation due to lack of access to primary care was identified as a possible mechanism for differences in LWBS,Reference Wright24 wait times,Reference Sonnenfeld, Pitts, Schappert and Decker18 and diagnostics.Reference Levas, Dayan and Mittal20 Notably, select studies on wait timesReference Haywood, Tanabe, Naik, Beach and Lanzkron32,Reference James, Bourgeois and Shannon33 and diagnosticsReference Pezzin, Keyl and Green19,Reference Levas, Dayan and Mittal20 found disparities between clinically similar cohorts.

Provider judgment and standardized care

Analgesia, diagnostics, and treatments received by minority patients were theorized to be impacted by the degree to which care is standardized.Reference Shafi and Gentilello22,Reference Ortega, Velden, Lin and Reid35,Reference Bazarian, Pope, McClung, Cheng and Flesher36,Reference Dickason, Chauhan and Mor37 Authors found that where provider judgment plays a larger role, disparities in treatment were larger (e.g., analgesic prescribing for “subjective” pain, such as back pain, v. “objective” pain associated with renal calculi).Reference Singhal, Tien and Hsia31,Reference Dickason, Chauhan and Mor37 Conversely, authors theorize that a lack of disparities in diagnostics and treatment for trauma patients may be explained by standardization of trauma care, although this was not investigated.Reference Shafi and Gentilello22,Reference Bazarian, Pope, McClung, Cheng and Flesher36

DISCUSSION

Interpretation of findings

Reviewed literature suggests that minority racial and ethnic groups experience disparities in analgesia, triage scores, wait times, diagnostics, treatments, rates of LWBS/AMA, and subjective experiences in the ED. Author-proposed explanations for disparities consist of: (1) conscious or unconscious bias, (2) patient-provider interactions, (3) facility and resource factors, (4) clinical presentations, and (5) provider judgment v. standardized care.

Authors identified bias, mistrust, language barriers, and social distance as related issues in patient-provider interactions. The fact disparities were noted where provider judgement plays a significant roleReference Singhal, Tien and Hsia31,Reference Dickason, Chauhan and Mor37 supports the idea that biases play a role in disparities. Factors such as overcrowding and resource disparities have an impact, but some studies demonstrate disparities between racial and ethnic groups within single hospitals.Reference Sonnenfeld, Pitts, Schappert and Decker18 Thus, differences between facilities do not necessarily explain disparities in population level studies.Reference Sonnenfeld, Pitts, Schappert and Decker18 Differences in clinical presentations were theorized to create disparities. However, some studies considering similar clinical cohorts found disparities remained, suggesting that differences in clinical presentation are not the sole cause.Reference Pezzin, Keyl and Green19,Reference James, Bourgeois and Shannon33

Strengths and limitations of this review

Ethnicity and race specific terms were limited given the tremendous number of ethnic and racial identity categories in use. As we were limited to English, we may have missed relevant articles in other languages. Additionally, thematic analysis involves researcher interpretation of data; thus, it is possible other reviewers may have developed different categories of author explanations for disparities.

Clinical and research implications

Many ED processes covered in this review are promising candidates for systematic reviews. Such reviews could focus on specific populations, contexts, or health conditions. Future studies are needed to disentangle issues of bias, patient-provider interactions, facility characteristics, and differences in clinical presentation. Although several studies found disparities in care for racial and ethnic minority groups, overt bias or institutionalized racism was rarely investigated and seldom discussed.Reference Sonnenfeld, Pitts, Schappert and Decker18,Reference James, Bourgeois and Shannon33 Literature on race and ethnicity in ED care is not up to date with evidence and perspectives within public health and social sciences.Reference Jones38,Reference Feagin and Bennefield39 In particular, the concept of “provider bias” has been critiqued for focusing attention primarily on individual prejudices, and obscuring the way individual prejudices are a product and mechanism of widespread inequities in privileges and access to resources.Reference Feagin and Bennefield39 Recognition of racism as a systemic problem could bring greater awareness to disparities and allow development of correcting measures.

CONCLUSION

This scoping review examined the literature on the impact of ethnicity and race on processes of ED care. Findings are mixed, but indicate that further research is needed to explore disparities in analgesia, wait times, triage scores, LWBS/AMA, subjective experiences, treatment, and diagnostics between racial and ethnic groups. Possible causes of these disparities, such as biases, patient-provider interactions, facility characteristics, and differences in clinical presentation, should be investigated in future research.

Financial support

The authors acknowledge the Alberta Health Services Population Public and Indigenous Health Strategic Clinical Network for their support of this project through their 2018 summer studentship award in the amount of $4500.

Competing interests

None declared.

Supplementary material

The supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2019.458.