CLINICIAN’S CAPSULE

What is known about the topic?

Children’s pain in the emergency department (ED) continues to be under-recognized and sub-optimally managed.

What did this study ask?

We sought to evaluate the frequency of caregiver/child acceptance of analgesia offered in the ED.

What did this study find?

Of the 743 children who presented to the ED with a painful condition, 408 (54.9%) were offered analgesia. If offered in the ED, analgesia was accepted by 91% (373/408) of the caregivers/children.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

This study suggests that caregiver/child refusal of analgesia is a not a major barrier to optimal pain management and highlights the importance of ED personnel in encouraging adequate analgesia.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the passing of a Decade of Pain Control and Research (2001–2010),Reference Nelson 1 there remains abundant evidence that children’s pain is sub-optimally managed in the emergency department (ED),Reference Ali, Chambers and Johnson 2 - Reference Friedrichsdorf, Postier and Eull 6 even in conditions associated with moderate to severe pain.Reference Kircher, Drendel and Newton 4 , Reference Brown, Klein, Lewis, Johnston and Cummings 7 , Reference Dong, Donaldson, Metzger and Keenan 8 The World Health Organization has stipulated that adequate pain management is a fundamental human right,Reference Brennan, Carr and Cousins 9 and the American Academy of Pediatrics reaffirmed its position that adequate analgesia should be provided for children in health care settings.Reference Fein, Zempsky and Cravero 10

Given recent public fears surrounding analgesia, and particularly opioids,Reference Abou-Karam, Dubé and Kvann 11 , Reference Basco 12 a possible barrier to the optimal provision of analgesia in the ED is caregiver or patient refusal. Although this has not been explored to date, current evidence suggests that caregivers harbour concerns surrounding harm,Reference Spedding, Harley, Dunn and McKinney 13 as well as the addictive potentialReference Abou-Karam, Dubé and Kvann 11 , Reference Rony, Fortier, Chorney, Perret and Kain 14 of analgesics. In addition, a discrepancy exists between survey data on the high clinician-reported use of analgesiaReference Poonai, Cowie and Davidson 15 , Reference Ali, Chambers and Johnson 16 and institutional audits of practice patterns that suggest otherwise.Reference Robb, Poonai and Thompson 17 , Reference Probst, Lyons, Leonard and Esposito 18 If the refusal of analgesia were identified as a barrier to adequate pain management for children, it would provide a compelling rationale for the development of educational strategies directed at dispelling misconceptions and encouraging acceptance of analgesia offered in the ED. Alternatively, if the offering of analgesia by health care providers were shown to be the rate-limiting step, then efforts to improve this should be undertaken. Our primary objective was to determine the proportion of caregivers/children who accepted analgesia in the ED. We also sought to determine the proportion of caregivers who were offered analgesia before ED arrival, caregiver perceptions of analgesia, confidence with managing pain at home, and satisfaction with ED care.

METHODS

Study design and setting

This was a two-centre cross-sectional study involving a survey and medical record review (MRR). Participants were recruited over a pre-specified 16-week period from the EDs of two Canadian pediatric centres from October 13, 2015, to February 2, 2016. Because of differences in the availability of research assistants (RAs), participants were recruited consecutively for three or five days per week, between 1800 and 2300 hours. Each ED has an average annual census of 40,000 and 58,000 visits. Ethics approval was obtained from the institutional ethics review board at each site.

Population

We included caregivers in attendance of children aged 4–17 years presenting to the pediatric ED from home with a primary complaint of either headache, otalgia, sore throat, abdominal pain, or musculoskeletal (MSK) injury within 24 hours of arrival and maximal pain rated by the child of >2/10 on the Faces Pain Scale–Revised (FPS-R).Reference Hicks, von Baeyer, Spafford, van Korlaar and Goodenough 19 We excluded children with a history of fever or vomiting in the previous 24 hours, chronic pain conditions, hypersensitivity to acetaminophen or ibuprofen, cognitive impairments precluding comprehension of study-related tasks, inability to tolerate oral medication, suspected non-accidental injury, not in attendance with a caregiver, and pregnancy. Potential participants were identified by an RA using the electronic tracking system in the ED. The RA performed eligibility screening and informed consent immediately after the bedside nursing assessment. Participants and RAs were unaware of the study hypothesis. Caregivers and patients were told that they were being surveyed to assess their opinions as to how pain should be managed prior to arrival and in the ED. RAs were told that the study was to explore the pain management practices of children at home and in the ED. They were not blinded to the survey questions but were unable to modify answers entered by participants.

Survey

The 27-item survey was developed using the approach outlined by Burns et al.Reference Burns, Duffett and Kho 20 in a de novo fashion without the use of an existing survey to guide question stems or responses. Item reduction was performed using the Delphi process.Reference Bolger and Wright 21 Following a nurse and physician assessment, we administered the first 19 questions. Immediately before discharge, we administered the final eight questions (see the Appendix). The survey was self-administered by the participant in anonymity using an iPad and hosted on the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform.Reference Harris, Taylor and Thielke 22 The caregivers completed surveys without any input from the child. Except for the child’s discharge pain score, caregivers and children were blinded to each other’s pain scores.

Medical record review

The MRR was limited to the physician and nursing charts and ambulance call report for the index visit. Two RAs performed the data extraction using a standardized data collection form, accompanied by a coding manual. Data were entered into a study-specific Excel spreadsheet (v. 14.3.8; Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Parameters related to the primary outcome were abstracted in duplicate, and data were double-checked for accuracy. From the MRR, we collected demographic data and type of analgesia accepted from emergency medical services (EMS) and ED personnel. It is standard practice at both sites to record medication in the medical chart, including those brought from home or used before arrival. All other outcomes were obtained from the survey.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the proportion of children and caregivers who accepted analgesia in the ED. Secondary outcomes included: the proportion of caregivers who offered analgesia prior to ED arrival; proportion of children offered analgesia in the ED; reasons for not offering analgesia prior to arrival and refusal in the ED; beliefs regarding harm and the addictive potential of analgesia; caregiver perception of their child’s pain using a 0–10 numerical rating scale (NRS); caregiver confidence in managing pain and satisfaction with care using novel five-item Likert scales (as no validated measures for these outcomes exist); children’s rating of their maximal pain in the 24 hours preceding arrival to the ED, immediately following the nursing assessment, and discharge using the FPS-R; and recollection of the reassessment of pain in the ED and discharge teaching on pain management. The NRS was chosen because it is frequently used and extensively validated in both adultsReference Dworkin, Turk and Farrar 23 and children.Reference Castarlenas, Jensen, von Baeyer and Miró 24 Importantly, the NRS correlates highly with the FPS-R.Reference von Baeyer, Spagrud and McCormick 25 , Reference Wong and Baker 26 The FPS-R is preferred by children,Reference de Tovar, von Baeyer and Wood 27 has been validated in children as young as four years of age,Reference Hicks, von Baeyer, Spafford, van Korlaar and Goodenough 19 and is also believed to be clinically useful in older children.Reference Gauthier, Finley and McGrath 28 The FPS-R is scored from zero (no pain) to ten (maximal pain).Reference Hicks, von Baeyer, Spafford, van Korlaar and Goodenough 19 The FPS-R and NRS were administered by the RA once the patient and caregiver had arrived into a bed.

Data analysis

Demographic, medical record, and survey data were summarized using means and standard deviations, medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), or percentages and frequencies, as appropriate. A bivariate analysis was conducted to examine the effect of the following a priori independent variables on the offering of analgesia in the ED: site, chief complaint, sex, child age, and pain score in the ED. If more than one variable was statistically significant, a multivariate analysis was performed using a stepwise logistic regression. A post hoc analysis was conducted to explore the relationship regarding the final MSK diagnosis (soft tissue injury, fracture, or dislocation) and offering analgesia in the ED. Estimates are presented as odds ratios and p-values with 95% confidence intervals. Data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical software package (v. 24, IBM SPSS, Armonk, New York). P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographics

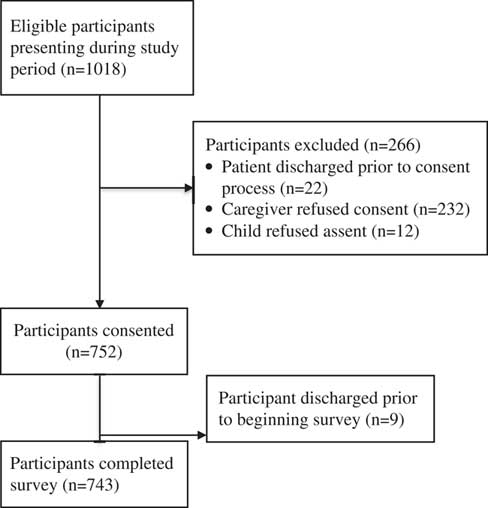

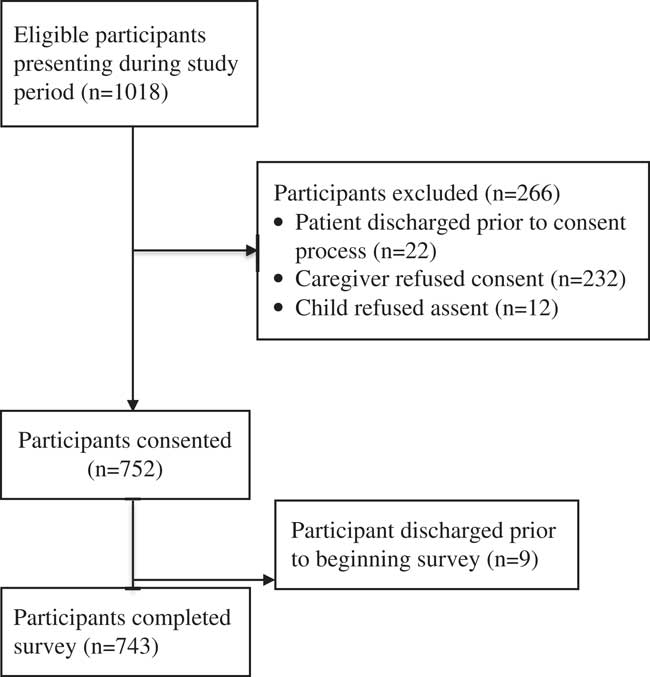

The proportion of participants who completed the survey was 743/1018 (72.9%); 248 were recruited at Site 1, and 495 were recruited at Site 2 (Figure 1). The demographic features of the caregivers and their children can be found in Table 1.

Figure 1 A flow diagram of participants.

Table 1 Demographic features of caregivers and children

ED=emergency department; FPS-R=Faces Pain Scale–Revised; IQR=interquartile range.

* Participant could choose more than one option.

Analgesia before ED arrival

In the 24 hours preceding ED arrival, the median (IQR) maximal pain rated by the children and caregivers was 8/10 (4) and 5/10 (2), respectively. Overall, 226/743 (30.4%) of the caregivers were offered some form of analgesia before arrival (site 1: 68/248, 27.4%; site 2: 158/495, 31.9%). In all cases, it was accepted by their child. Table 2 describes reasons provided by the caregivers for not offering analgesia before arrival.

Table 2 Reasons given by caregiver for not offering analgesia prior to ED arrival or accepting analgesia that was offered in the ED

N/A=not applicable.

* Caregiver could choose more than one option.

Of the 60 children who arrived by EMS, none were offered analgesia by their caregivers. EMS personnel offered analgesia to 11/60 (18.3%) of the children, and analgesia was accepted by all but one case.

Analgesia in the ED

In the ED, the median (IQR) pain score reported by children immediately following the nursing assessment was 8/10 (2). Analgesia was offered by the nurse (330/743, 44.4%) or physician (78/743, 10.5%), or it was not offered at all (335/743, 45.1%). If offered, analgesia was accepted by 373/408 (91.4%) of the caregivers and children. The median (IQR) time between the completion of the triage assessment to receiving analgesia was 24 (74) minutes. Analgesia included ibuprofen (207/373, 55.5%), other non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDS; 60/373, 16.1%), acetaminophen (35/373, 9.4%), opioids (29/373, 7.8%), or non-pharmacologic therapies alone (42/373, 11.3%). The latter included ice alone (21/373, 8.3%), splinting alone (5/373, 1.3%), ice with splinting (10/373, 2.7%), and distraction with ice (6/373, 7.8%). Reasons for not accepting analgesia in the ED are detailed in Table 2. Overall, 414/743 (55.7%) of the children were offered some type of analgesia by caregivers, EMS, or ED personnel. In a bivariate analysis, variables with a p-value of≤0.05 were included in a multivariate analysis (child age, pain score in the ED, and chief complaint). In the multivariate analysis, the overall model including chief complaint, child age, and pain score in the ED was significant (p<0.001). The odds of being offered analgesia in the ED was significantly greater if the child was older (OR 1.1, 95% CI 1.1–1.2, p=0.04), reported more severe pain in the ED (OR 1.1, 95% CI 1.1–1.3, p=0.04), or was diagnosed with a fracture (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.3–3.4, p=0.003). However, the odds of being offered analgesia in the ED was significantly lower if the child presented with abdominal pain (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.4–0.9, p=0.02) (Table 3). Caregiver perceptions of analgesia are shown in Table 4.

Table 3 Offering analgesia in the ED

ED=emergency department; FPS-R=Faces Pain Scale–Revised; IQR=interquartile range; OR=odds ratio.

* Represents percentage of the total for each row.

Table 4 Caregiver perceptions of analgesia (N=743)

Confidence managing pain and satisfaction with ED care

Of the 714 families discharged from the ED, 392 (55%) recalled receiving education from the nurse or physician on pain management at home. The median (IQR) pain score on the FPS-R at discharge was 6/10 (4). In terms of managing their child’s pain at home, caregivers reported their confidence as “very” in 493/742 (66%), “somewhat” in 196/742 (26%), “neutral” in 26/742 (4%), “somewhat unsure” in 24/742 (3%), or “very unsure” in 3/742 (1%). Caregivers rated their child’s pain management in the ED as “very well” in 405/722 (56%), “somewhat well” in 98/722 (14%), “neutral” in 167/722 (23%), not “as well as it could have been” in 39/722 (5%), or “not well at all” in 13/722 (2%). Caregivers rated their satisfaction with the overall care as “very satisfied” in 525/738 (71%), “somewhat satisfied” in 143/738 (19%), “neither satisfied nor unsatisfied” in 49/738 (7%), “somewhat unsatisfied” in 16/738 (2%), or “very unsatisfied” in 5/738 (1%).

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that caregiver/child refusal of analgesia is likely not a major barrier to pain management in the pediatric ED. Importantly, however, the frequency of caregivers and ED personnel offering analgesia is suboptimal. Our findings underscore the need for strategies to educate children, caregivers, and ED personnel on the importance of accurate measurement and adequate management of pain both before and during acute medical care.

A large proportion of caregivers who did not offer analgesia before arrival accepted it once in the ED. This implies that caregivers look to ED providers for guidance on whether pain should be treated. For clinicians, this finding highlights the importance of offering analgesia and providing appropriate caregiver education. Refusal of analgesia has been described in a greater proportion (49%) of adult ED patients, most commonly because of possible obscuration of the diagnosis.Reference Allione, Melchio, Martini, Dutto, Ricca and Bernardi 29 However, we found that children’s unwillingness to take medication was the main reason for refusal. A survey of Greek school-aged children found that most believe “strongly in the therapeutic power of medicine” and obtain information from physicians, parents, and reading.Reference Bozoni, Kalmanti and Koukouli 30 This suggests that caregivers and clinicians are in a position to substantially influence children’s perceptions on medication and educate them on the importance of expressing pain.

The proportion of caregivers offering any type of analgesia before arrival was low, even across sites, suggesting that this problem is not centre specific. Our findings are consistent with a report that only 26%–37% of children with MSK injuries received prehospital pharmacologic analgesia.Reference Maimon, Marques and Goldman 31 This was concerning because the median FPS-R score of 8/10 would be considered severeReference Tsze, Hirschfeld, Dayan, Bulloch and von Baeyer 32 and consistent with a child’s perceived need for medication.Reference Gauthier, Finley and McGrath 28 The most common reason for not offering analgesia at home, a lack of time (41%), was surprising given that the median duration of pain before ED arrival was four hours, possibly reflecting a social desirability bias. The prevalence of caregiver concerns regarding masking the diagnosis (19%) and the severity of the condition (18%) are consistent with previous findings in the context of children’s MSK pain.Reference Maimon, Marques and Goldman 31 Most caregivers (91%) reported being able to tell if their child was in pain and 85% reported giving their child analgesia in the past. These findings and the fact that caregivers rated their child’s pain as 5/10 on the NRS (moderate pain),Reference Collins, Moore and McQuay 33 suggests that caregivers may have underestimated their child’s pain. This finding must be interpreted cautiously, as there have been no studies that have explored the degree of correlation between the NRS and FPS-R for preschool children. Nevertheless, a poor correlation between parental and children’s pain scores has been describedReference Kelly, Powell and Williams 34 - Reference St-Laurent-Gagnon, Bernard-Bonnin and Villeneuve 36 and raises the possibility that caregivers may not be able to assess the degree of their child’s pain accurately. Caregivers are most often the gatekeepers to providing analgesia to children and their fears surrounding medication, particularly, opioids are prevalent, and may influence their decision-making.Reference Basco 12 Our findings emphasize the need for strategies to educate caregivers on the importance and accurate measurement of acute pain in children so rational, evidence-informed analgesic choices can be made.

Our finding of the infrequent provision of analgesia (18%) by EMS providers should be interpreted with caution because of regional differences in care directives. Nevertheless, previous studies have also described the suboptimal provision of analgesia to children by EMS providers.Reference Kircher, Drendel and Newton 4 , Reference Rutkowska and Skotnicka-Klonowicz 37 , Reference Swor, McEachin, Seguin and Grall 38 A significant barrier identified by EMS personnel is an inability to assess children’s pain accurately,Reference Rahman, Curtis and DeBruyne 39 and this should be a focus of educational initiatives.

Forty-five percent of children were not offered analgesia in the ED, consistent with a large pre-existing body of evidence.Reference Ali, Chambers and Johnson 2 , Reference Spedding, Harley, Dunn and McKinney 13 , Reference Todd, Ducharme and Choiniere 40 - Reference Weng, Chang and Lin 43 Dong et al. also reported that 59% of children with isolated long bone fractures received no analgesia within the first hour of arrival,Reference Dong, Donaldson, Metzger and Keenan 8 and Kircher et al. reported that 62% of children with MSK injuries received no analgesia.Reference Kircher, Drendel and Newton 4 In our sample, the median pain score following a nursing assessment was 8/10, highlighting the possibilities that pain was either not reassessed, reassessed but misinterpreted, or underestimated altogether. Kircher et al. also found that just over one-quarter of patients in a pediatric ED had a reassessment of pain scores documented.Reference Kircher, Drendel and Newton 4 Our finding that analgesia was significantly more likely to be offered if the child was older and in more severe pain is supported by robust evidence that younger children are significantly less likely to receive analgesia.Reference Kircher, Drendel and Newton 5 , Reference Brown, Klein, Lewis, Johnston and Cummings 7 , Reference Probst, Lyons, Leonard and Esposito 18 , Reference Alexander and Manno 44 , Reference Dohrenwend, Fiesseler, Cochrane and Allegra 45 Possible explanations include uncertainty with medication dosing, fear of adverse effects, and the inability of young children to verbalize their needs.Reference Kircher, Drendel and Newton 5 , Reference Alexander and Manno 44 Offering analgesia in the ED was also positively related to more severe pain. To our knowledge, this association has not been previously described and emphasizes the importance of a pain assessment upon arrival to the ED. ED staff interventions such as audit and feedback for accurate interpretation of pain scores and the importance of reassessment are important steps toward timely, effective, and consistent pain management. Not surprisingly, children presenting with abdominal pain were less likely to be offered analgesia in the ED. This is consistent with previous findingsReference Kim, Galustyan, Sato, Bergholte and Hennes 46 - Reference Jawaid, Masood and Ayubi 48 and possibly linked to a historical misconception that analgesia may mask the signs of surgical pathology.Reference Falch, Vicente and Häberle 49 , Reference Nissman, Kaplan and Mann 50 However, recent evidence has contested this belief.Reference Poonai, Paskar and Konrad 51

Almost one-fifth of caregivers believed opioids to be harmful and addictive, consistent with emerging literature highlighting caregiver fears surrounding analgesia, particularly opioids.Reference Abou-Karam, Dubé and Kvann 11 , Reference Basco 12 , Reference Rony, Fortier, Chorney, Perret and Kain 14 Interestingly, a large proportion of caregivers was unsure regarding the potential for addiction (20%) and harm (24%) associated with opioids. These findings further emphasize the need for comprehensive caregiver education on indications for opioids and associated risks and benefits. The recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for opioids in chronic painReference Dowell, Haegerich and Chou 52 and evidence that prescription opioid use in childhood is associated with misuse as adults,Reference Miech, Johnston, O’Malley, Keyes and Heard 53 suggesting that even clinicians need more clarity and direction on the long-term effects of short-term opioid use.

Pain severity at discharge is not predictive of caregiver satisfaction.Reference Ali, Weingarten and Kircher 54 , Reference Magaret, Clark, Warden, Magnusson and Hedges 55 Therefore, we assessed both global satisfaction with care and satisfaction specific to pain management. Global judgments of satisfaction with treatment is a core outcome domain outlined by the Pediatric Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (Ped-IMMPACT) consensus.Reference McGrath, Walco and Turk 56 The majority of caregivers (90%) reported being either very or somewhat satisfied with their child’s care despite ongoing pain at discharge. Importantly, a smaller proportion believed that their child’s pain was managed either somewhat or very well (70%), and almost one-quarter reported it as neutral (23%). Although the median value of pain at discharge was 6/10, constituting a clinically meaningful change from the beginning of the ED visit,Reference Bulloch and Tenenbein 57 it represents moderate painReference Tsze, Hirschfeld, Dayan, Bulloch and von Baeyer 32 and a perceived need for pharmacologic intervention.Reference Brennan, Carr and Cousins 9 , Reference Gauthier, Finley and McGrath 28 Pain relief in the ED is associated with an intent to comply with the discharge instructions,Reference Downey and Zun 58 and caregiver satisfaction with pain management is highly correlated with pain relief in their child.Reference Gill, Drendel and Weisman 59 Leaving the ED with inadequate treatment of pain is associated with suboptimal management of pain at home.Reference Gill, Drendel and Weisman 59 Our findings highlight that there is room for improvement in how ED personnel manage children’s pain and influence postdischarge care. This may be accomplished through previously described successful knowledge translation initiatives that incorporate education, reminders, audit, and feedback.Reference Treadwell, Franck and Vichinsky 60 Our results can likely be extrapolated across Canada because the delivery of care and structure of ED health care delivery across provinces is fairly homogenous. However, our results may not be readily generalizable to other countries where allied health personnel have different responsibilities.

LIMITATIONS

The FPS-R and NRS have not been validated for retrospective assessments and may be subject to recall bias.Reference Noel, Palermo, Chambers, Taddio and Hermann 61 Reporting past pain may serve to convey what the individual has “endured or how they coped,”Reference Jaaniste, Noel and von Baeyer 62 possibly inflating the severity of the actual experience. However, this approach was the single best available strategy for the assessment of pre-arrival pain. It is possible that differences between parental perception of pain and pain reported by a child could have been because of different scales, but it is unlikely given the high correlation between the NRS and FPS-R.Reference von Baeyer, Spagrud and McCormick 25 , Reference Wong and Baker 26 Retrospective pain assessments in children are commonly used,Reference Ali, Weingarten and Kircher 54 , Reference Jaaniste, Noel and von Baeyer 62 and although evidence specific to pain is lacking, the ability to accurately recall states such as hunger appear to be present from age four onwards.Reference Gopnik and Slaughter 63 There is also good agreement between the pain questionnaires with a short recall interval (14 days) and prospective pain diaries.Reference Self, Williams, Czyzewski, Weidler and Shulman 64 Global measures of confidence managing pain and satisfaction with ED care were likely dependent on factors not directly measured, such as previous experience with health care and wait time. Although others have used similar scales to measure caregiver perceptions in the context of pain,Reference Ali, Weingarten and Kircher 54 the results of these outcomes should be interpreted cautiously. Second, we did not record whether pain scores were documented at triage. However, no association has been found between pain score documentation at triage or the severity of pain scores and provision of analgesia to children.Reference Weng, Chang and Lin 43 Third, our results may not reflect an actual practice setting as willing study participants might have been more motivated to manage their child’s pain, and participant recruitment before physician assessment might have heightened caregiver sensitivity toward pain management. These factors may have inflated the proportion of caregivers who accepted analgesia in the ED. Finally, we were unable to determine if ED personnel reassessed pain reliably. Although this has been cited as a pervasive issue for children in the ED,Reference Herd, Babl, Gilhotra and Huckson 3 reassessments might not have been documented. The fact that the median pain score at discharge was in the moderate range suggested that even if pain reassessments were performed, accurate information might not have been obtained or interpreted correctly.

CONCLUSIONS

Caregiver/child refusal of analgesia in the ED is infrequent and unlikely to be a major reason for the well-described suboptimal management of children’s pain. However, given the possible biases associated with this study design, our estimate of the acceptance of analgesia may not apply to a practice setting outside the context of this study. Given that over 90% of caregivers accepted an offer of analgesia, ED physicians likely exert a significant influence on the pain management of children. A large proportion of children in severe pain are not offered analgesia by ED personnel or their caregivers. This emphasizes the need for educational interventions targeting children, caregivers, and ED personnel on the importance of adequate reporting, assessment, reassessment, and interpretation of pain scores to provide timely, effective, and universal management of pain from its onset to resolution.

Competing interests

This work was previously presented at the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians Annual Meeting June 2016, Quebec City, QC; and American Academy of Pediatrics Annual Meeting October 2016, San Francisco, CA, USA. This study was unfunded.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2018.11