INTRODUCTION

Facing concerns about deficiencies in current educational and assessment processes, medical education is evolving rapidly to meet the complex needs of our learners, administrative organizations, and the public.Reference Holmboe, Sherbino and Englander1 Specifically, the transition to competency-based medical education has placed an increased onus on training programs and systems to ensure that graduating trainees meet key competencies before entering independent practice.Reference Frank, Snell and Sherbino2 To achieve this, education leaders have proposed an increase in the use of direct workplace-based observation to assure that these competencies are met.Reference Harris, Bhanji and Topps3 However, in emergency medicine (EM) and many other clinical workplaces, experiences are not predictable. This results in significant variability across trainees in the competencies that may be opportunistically assessed.Reference Wang, Quinones and Fitch4 Further, the high acuity inherent to EM requires that patient care be prioritized over trainee assessment.

Simulation-based assessment has been proposed as a potential solution to this problem,Reference Griswold, Fralliccardi and Boulet5 with the capacity to control exposure to scheduled reproducible experiences and allow trainees to demonstrate their abilities without any risk to patient safety.Reference Ziv, Wolpe, Small and Glick6 From occasional low-stakes assessment to higher-stakes examination, there has been increasing use of simulation-based assessment across medical specialities.Reference Chiu, Tarshis and Antoniou7 In Canadian EM, few training programs had implemented simulation-based assessment by 2017,Reference Russell, Hall and Hagel8 but this number is steadily rising. There is literature supporting the translational outcomes (e.g., improved performance and patient care) of simulation-based trainingReference McGaghie, Issenberg, Barsuk and Wayne9,Reference Brydges, Hatala, Zendejas, Erwin and Cook10 but limited evidence directly correlating simulation-based assessment to real-world performance.Reference Weersink, Hall, Rich, Szulewski and Dagnone11 While, in principle, the simulated environment seems ideal for assessment, there are several tensions or concerns that stakeholders have raised. For example, simulation was initially developed as a “safe space” for practice,Reference Rudolph, Raemer and Simon12 and the introduction of assessment may threaten the integrity of this learning environment, with trainees fearing negative assessment. Another concern is variable access to simulation equipment and how this may disadvantage trainees and programs with resource limitations.

Despite these tensions, program directors and educators have been tasked with the rapid integration of simulation-based assessment into programs of assessment without a clear understanding of how best to use it effectively. To assist those responsible for the implementation of simulation-based assessment, it was an aim of the 2019 Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) Academic Symposium on Education to review the literature pertaining to simulation-based assessment and develop a set of consensus-based and expert-informed recommendations on the use of simulation for assessment. In this paper, we describe these recommendations for simulation-based assessment, organized by the Consensus Framework for Good Assessment of Norcini et al.,Reference Norcini, Anderson and Bollela13 to assist educators in the era of competency-based medical education.

METHODS

In May 2019, the Academic Section of the CAEP held its annual consensus conference on education. In preparation for this conference, a working group of emergency physicians and content experts was formed with representation from multiple institutions across Canada. Members were chosen based on their experience and expertise in medical simulation, assessment, or both, having completed degrees in medical education or advanced training in simulation. Monthly teleconference meetings were held to design and implement the study. To obtain a final product of consensus-based recommendations for simulation-based assessment, a scoping literature review was first performed to identify principles of simulation-based assessment. These principles were used to derive a set of recommendations that were revised using a national stakeholder survey. Finally, they were presented and revised at the consensus conference to generate a final set of recommendations on the use of simulation-based assessment in EM. This study received approval from the Queen's University Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board (REB #6023280)

Scoping review

With the aid of a university librarian, we performed a scoping reviewReference Arksey and O'Malley14 to collate existing literature on the use of simulation-based assessment in medical education. MEDLINE, EMBASE, and ERIC databases were searched, along with Google Scholar, in October 2018 using “and/or” combinations of the following keywords: “simulation,” “manikins,” “assessment,” “competence,” “residency,” and “medical education.” All searches were limited to English-language papers published in or after the year 2000. All papers were initially screened for inclusion by title and, then, abstract by two study investigators (AKH and TC). Papers were included if they either: 1) made recommendations on the use of technology-enhanced simulation for assessment in medical education; or 2) investigated the use of technology-enhanced simulation to assess physician learners at any stage in training or practice. As described by Cook et al.,Reference Cook, Brydges, Zendejas, Hamstra and Hatala15 technology-enhanced simulation was defined as any activities involving manikins, task trainers, virtual reality, or computer-based simulations. Papers were excluded if they pertained to technical surgical competence-assessment only, competence in procedures not relevant to EM practice (e.g., laparoscopic surgery), computer-based virtual patients requiring only standard computer equipment, or utilized human patient actors only. Papers were assigned to one of two categories: 1) practical examples of simulation-based assessment; or 2) reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, guidelines, or consensus papers pertaining to simulation-based assessment.

Full-text reviews of included papers were completed independently by six (KC, NR, RW, TM, AP, and CD) investigators to characterize principles of simulation-based assessment. Two investigators (AKH, TC) compiled these principles and summarized and grouped them using a thematic analysis involving the Consensus Framework for Good Assessment.Reference Norcini, Anderson and Bollela13 The thematic analysis followed the technique described by Arksey and O'Malley.Reference Arksey and O'Malley14 To enhance rigour, all other study investigators reviewed and edited the groupings to generate a final list by consensus. All study authors then independently reviewed the extracted principles and translated them individually into actionable recommendations. Two study authors (AKH, TC) compiled and summarized the list of recommendations. This list was then revised by all study authors at two meetings to create a draft set of recommendations on the use of simulation-based assessment.

Papers found in the literature search and identified as practical examples of simulation-based assessment were reviewed by the study investigators and assigned to one or more of the derived recommendations.

Stakeholder survey

We distributed the draft recommendations on simulation-based assessment to 81 simulation and education experts across the Canadian EM community, representing all Fellow of the Royal College of Phsyicians of Canada (FRCPC)-EM training programs. Using a Qualtrics online survey (Provo, UT), we asked respondents to review the recommendations and answer two free-text questions: 1) what changes would you make to the recommendations; and 2) what other recommendations regarding the use of simulation-based assessment in EM should be added? We distributed the survey to three groups of individuals: 1) Canadian EM residency program directors; 2) Canadian EM Simulation-Educators Research Collaborative members (EM-SERC); and 3) EM simulation educators identified as part of a prior study identifying curricular content for EM simulation-based education.Reference Kester-Greene, Hall and Walsh16 The study authors reviewed and collated all responses and created a second draft set of recommendations for SBA.

Consensus conference

We presented the revised recommendations to 60 participants at the CAEP Academic Symposium on Education Scholarship Consensus Conference in Halifax, Nova Scotia, on May 25, 2019. We asked participants to reflect on four vignettes (Appendix A), each designed to highlight the tensions related to simulation-based assessment, to provide participants with a pragmatic context of the use of simulation-based assessment. In small groups, participants then reviewed, discussed, and provided written feedback on the proposed recommendations. Two study authors (AKH, TC) collated, discussed, and incorporated the feedback into the recommendations, generating a final consensus list of recommendations.

RESULTS

Literature review

The literature search is outlined in Figure 1. The database search yielded 2,570 citations after duplicates were removed. Title review excluded 1,871 citations, and abstract review excluded another 501 citations, leaving 198 for full-text review. In addition, six papers were added by study coauthors, and two were found after screening the manuscript reference lists. In total, we performed a full-text review of 206 papers, excluding 37, allocating 119 to the examples of simulation for assessment category, and the remaining 50 to the reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, guidelines, and consensus papers category.

Figure 1. Flow diagram for literature search.

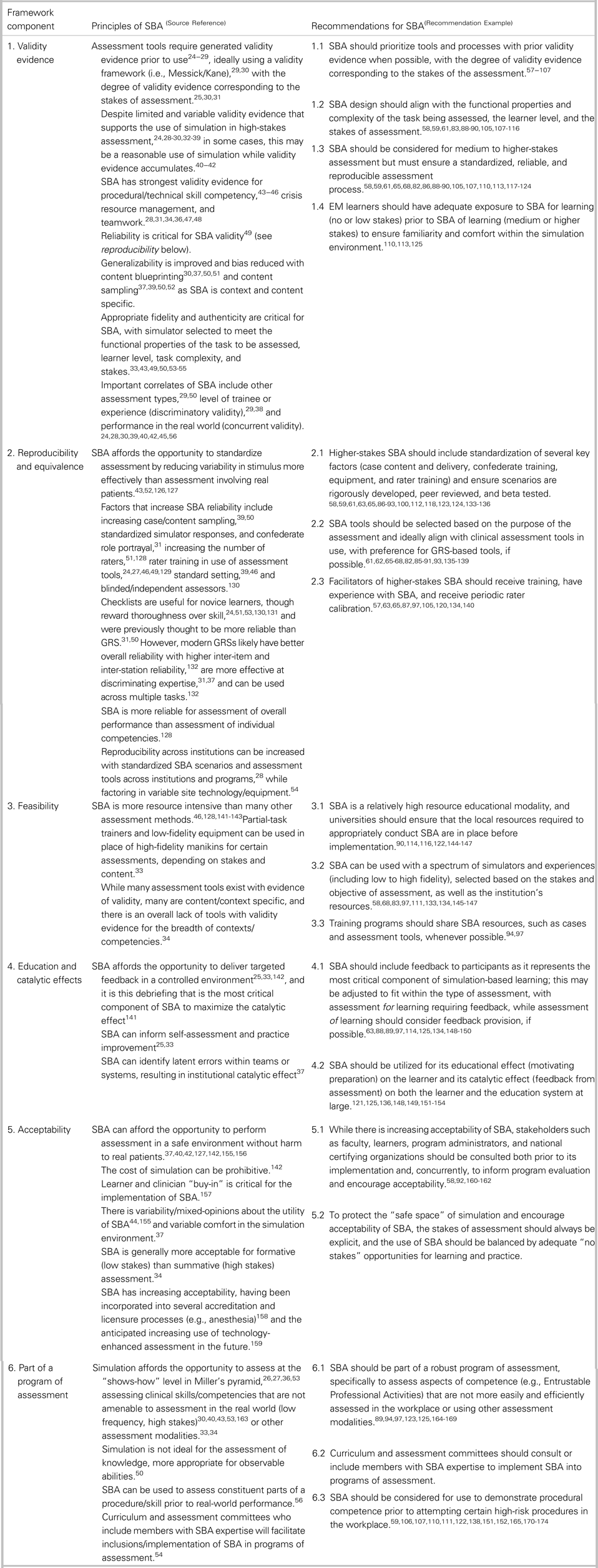

After analysis of the reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, guidelines, and consensus papers, 209 principles of simulation-based assessment were extracted. These were condensed and summarized by thematic analyses and reviewed by study authors to create a list of 29 principles (Table 1). Informed by these principles of simulation-based assessment, study authors generated an initial 16 recommendations organized by the Consensus Framework for Good Assessment.Reference Norcini, Anderson and Bollela13 Further, the identified practical examples of simulation-based assessment from the literature search can be found. listed in superscript, after each relevant recommendation (Table 1).

Table 1. Detailed recommendations for the use of simulation-based assessment in Canadian EM education and training

EM = emergency medicine; GRS = Global Rating Scales; SBA = simulation-based assessment.

References found in Appendix B.

Stakeholder survey

Of the 81 invited stakeholders, 33 (41%) responded, representing 12 of the 14 Canadian FRCPC-EM training programs. Fifteen respondents identified themselves as simulation educators, 13 identified themselves as program directors, and 5 did not identify their educational role. The recommendations were revised based on survey feedback, and one additional recommendation was incorporated.

Summary of recommendations

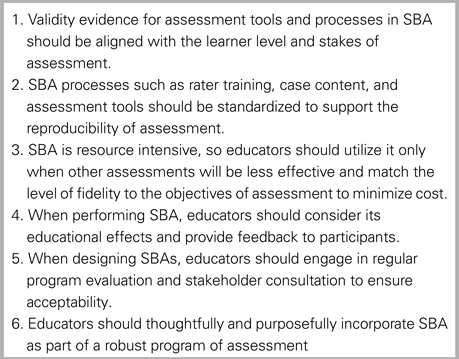

We collated and summarized the feedback from the 60 participants at the 2019 CAEP Academic Symposium on Education Scholarship Consensus Conference. The final 6 summary recommendations and 17 detailed recommendations for simulation-based assessment are listed in Tables 1 and 2. The papers referenced in Table 1 can be found in Appendix B.

Table 2. Summary recommendations for the use of simulation-based assessment in Canadian EM education and training

SBA = simulation-based assessment.

DISCUSSION

Using a comprehensive process for a literature review, national multi-level stakeholder consultation, and consensus generation, we have developed a set of recommendations for the use of simulation for assessment. Grounded in established principles of good assessment,Reference Norcini, Anderson and Bollela13 these recommendations are intended to be pragmatic and feasible for frontline educators.

How to use this report

This report is important for educators, program directors, and simulation leaders as they seek to implement simulation-based assessment and collectively navigate this transformative time for postgraduate medical education. Deconstruction of the principles of assessment makes this seemingly large undertaking more manageable and accessible. These recommendations can be used as both a guide to ensure the effective implementation and use of simulation-based assessment, as well as a tool to promote and advocate for high-quality simulation-based assessment. The utility of this report will vary depending on the institution and their existing simulation infrastructure and assessment processes. For some, this may be used as a reference tool to review programs of assessment systematically that already include simulation-based assessment. For others, this may be used to advocate for resources in order to establish a program of assessment that leverages the potential of simulation-based assessment, enabling assessment of performance in domains that are otherwise difficult to capture and illuminating the “blind spots” in current programs of assessment.

Notable findings

As with any assessment method, it is important to question the validity of the assessment process and the decisions that are made based on that assessment (e.g., pass/fail). As our literature review revealed, there is a strong and growing body of validity evidence supporting the use of simulation-based assessment such that we can proceed comfortably using simulation for both lower-stakes assessment and the assessment of specific aspects of competence such as procedural competence and crisis resource management.Reference Cook, Brydges, Zendejas, Hamstra and Hatala15 Simulation-based assessment is likely best used for the assessment of observable skills, attitudes, and behaviours and is less suited for the assessment of knowledge. Ideally, educators should seek out tools and processes that have been evaluated, capitalizing on work that has already been done and adapting to local contexts. As we increase the stakes of the assessment, the demand increases for validity evidence for the assessment process.Reference Cook, Brydges, Ginsburg and Hatala17 We recommend that EM programs in Canada start using simulation-based assessment initially with tools and processes that have some form of validity evidence when possible. We also challenge the EM community to continue developing validity evidence for more simulation-based assessment tools and programs and, in particular, for competencies that are not otherwise easily assessed.

One of the main advantages of simulation is its inherent potential for standardization; the assessment environment can be controlled to deliver the same “stimulus” to all learners. This gives simulation-based assessment a powerful and unique advantage over traditional workplace-based assessment. However, the challenges in delivering such standardized assessments cannot be overstated. Simulation-based assessment is resource intensive, as compared with most existing methods of assessment. With a need to focus on standardization of scenario delivery, training of confederates, and rater training, the costs and efforts to deliver high-quality assessment can become prohibitive. It is important to remember that high-fidelity simulation equipment is not required to conduct simulation-based assessment. Depending on the assessment objectives, task trainers and low-fidelity equipment may be the optimal choices to achieve functional task alignment.Reference Hamstra, Brydges, Hatala, Zendejas and Cook18 Simulation-based assessment resources such as cases or assessment tools should be shared between programs whenever possible to improve access to the highest quality simulation content.

While the benefits of using simulation for medical education are well articulated,Reference McGaghie, Issenberg, Barsuk and Wayne9,Reference McGaghie, Issenberg, Cohen, Barsuk and Wayne19 the educational effect (the learning that takes place before the assessment) and catalytic effect (the learning that is stimulated by the assessment) of simulation-based assessment have not been well defined. Effective assessment should encourage both of these and promote the learner's progression to competence.Reference Norcini, Anderson and Bollela20 Literature suggests that much of the learning that occurs in simulation is a direct result of timely, objective, and constructive feedback from both peers and faculty involved in the debriefing process.Reference Lateef21 Therefore, we must ensure that processes of simulation-based assessment do not become hurdles to overcome but rather opportunities for concrete feedback, reflection, and enhanced performance.Reference Harrison, Könings, Schuwirth, Wass and van der Vleuten22

Simulation-based assessment will not succeed if the training programs, content creators, assessors, and participants are not involved in its planning, implementation, and review. If trainees no longer look forward to learning in the simulation lab because of a poorly designed simulation-based assessment, we will lose the learning environment that we have worked so hard to create. The simulation environment is artificial and requires experience for learners to become comfortable, thus making frequent exposure in low-stakes contexts critical if we are to also use it for assessment. Further defining the stakes of any simulation-based activity can help set the stage for trainee comfort with a shared understanding of expectations and clarity of purpose.Reference Watling and Ginsburg23

LIMITATIONS

While the scope of the literature search was broad, articles retrieved were limited to the English language. Additionally, given the number of articles to be reviewed, each paper was read in detail by a single reviewer; thus, we cannot rule out that some subjectivity may exist in the interpretation and extraction of the key recommendations by individual reviewers who screened the papers. Lastly, the structure of the key recommendations aligns with the 2018 Consensus Framework for Good AssessmentReference Norcini, Anderson and Bollela13; however, we acknowledge that there are other assessment frameworks in existence that may offer different insights into the use of simulation-based assessment.

CONCLUSION

We have proposed a set of recommendations that may serve as a guide in the implementation of simulation-based assessment, as well as advocate for its use with competency-based medical education. While debates regarding simulation-based assessment will (and should) continue until simulation-based assessment has found its thread in the fabric of competency-based medical education, these consensus recommendations, grounded in literature and expert review, should add to the momentum of this important assessment modality.

Supplemental material

The supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2019.488.

Acknowledgements

The study authors would like to thank Jeff Perry as the chair of the CAEP Academic Section, Ian Stiell as the CJEM Editor-in-Chief, and all participants who attended the 2019 CAEP Academic Symposium on Education.

Competing interests

This work was supported by the CAEP Academic Section.