A 22-year-old male presented to the emergency department due to progressive odynophagia and dysphagia. He underwent a left third mandibular molar extraction at the dental clinic a week prior. At the emergency department, vital signs were normal except tachycardia (114/min) and tachypnea (22/min). A physical examination revealed bilateral neck tenderness with crepitus on palpation, no stridor or acute airway compromise signs. Laboratory data showed leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 19000/cumm; segmented, 91%) and elevated C-reactive protein (1.07 mg/dL). Radiographs showed the presence of prevertebral emphysema on the C-spine lateral view (Figure 1) and subcutaneous emphysema with pneumomediastinum on the chest posteroanterior view (Figure 2). A non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed the radiographic findings; additionally, there was gas collection over the pericarotid, pericardial (Figure 3) and extradural spaces (Figure 4). Because there was no CT evidence of infectious signs and clinical features were stable, conservative treatment with intravenous amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was given for a week. Clinical symptoms improved, and a follow-up CT showed no residual gas.

Figure 1 C-spine radiographs (left lateral view) show prominent subcutaneous and prevertebral emphysema from the base of the skull to the mediastinum.

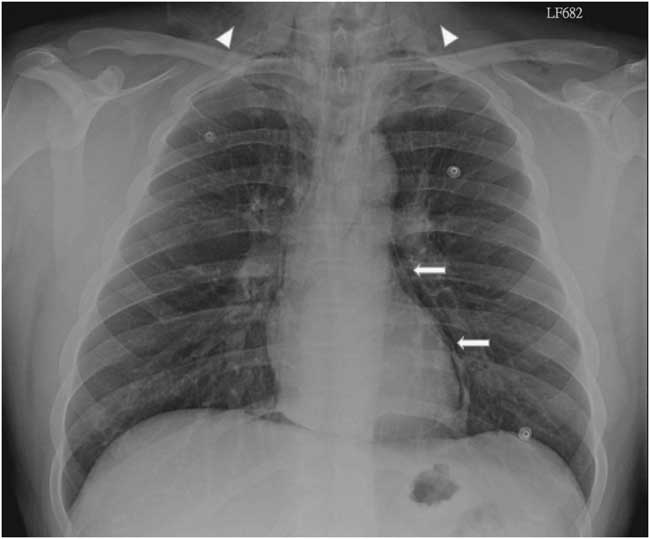

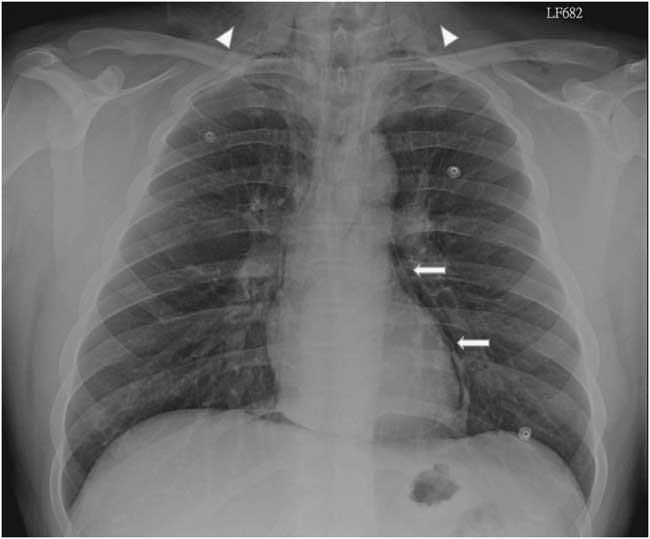

Figure 2 Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows subcutaneous emphysema (arrow heads) and pneumomediastinum (arrows).

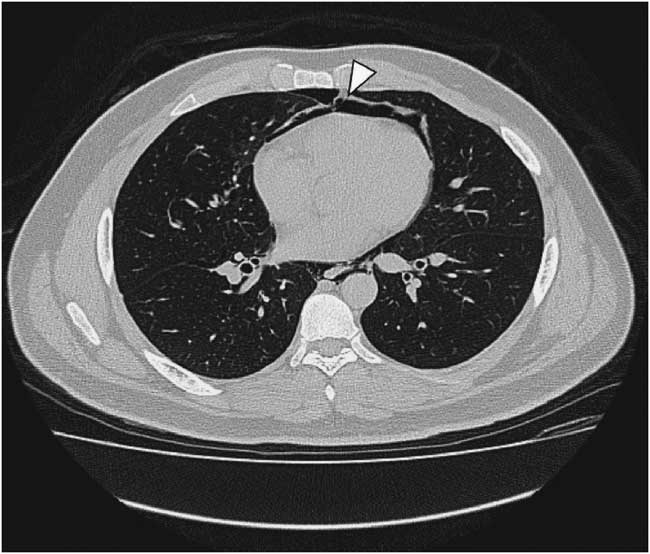

Figure 3 Non-contrast chest computed tomography shows pneumopericardium (arrowhead).

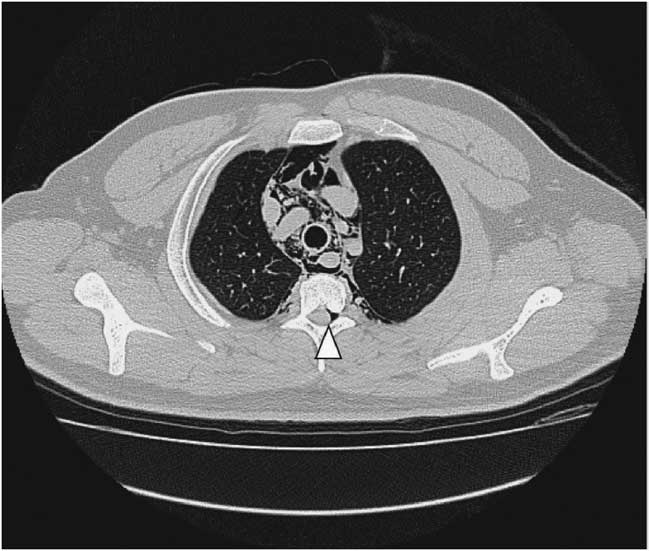

Figure 4 Non-contrast chest computed tomography shows gas collection at thoracic extradural space: pneumorrhachis (arrowhead).

Although subcutaneous emphysema is a rare complication following dental procedures, with mostly benign and self-limiting sequelae, it may progress to fatal consequences such as cardiac tamponade, air embolism, pneumothorax, and mediastinitis.Reference Goodnight, Sercarz and Wang 1 There have been reports correlating subcutaneous emphysema and dental treatments with the use of air turbine hand-pieces and air syringes.Reference McKenzie and Rosenberg 2 , Reference Arai, Aoki and Yamazaki 3 CT is useful to detect the precise extension of gas dissection, such as pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, and pneumorrhachis, in this case.Reference Ehmann, Paziana and Stolbach 4 Most importantly, CT can evaluate the complications of extensive emphysema or infectious process. In addition, it can guide clinical treatment decisions like the need for urgent tracheostomy or fasciotomy.

Competing interests: None declared.