CLINICIAN'S CAPSULE

What is known about the topic?

Vomiting is common in children presenting to the emergency department after a minor head injury; however, the clinical importance is unclear.

What did this study ask?

What is the value of the number and timing of vomiting episodes after pediatric minor head injury in predicting intracranial injury?

What did this study find?

Probability of intracranial injury in children with vomiting increases with the number of vomiting episodes and the presence of other high-risk factors.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

This information will help clinicians determine who requires a computed tomography scan after minor head injury.

INTRODUCTION

Minor head injury is a common reason for children to visit the emergency department (ED).Reference Taylor, Bell, Breiding and Xu1 Computed tomography (CT) scans are widely used to evaluate head injury and rule out intracranial injury in the ED; however, with this comes increased exposure to ionizing radiation and cost.Reference Klassen, Reed and Stiell2–Reference Menoch, Hirsh, Khan, Simon and Sturm4 Previous research has shown that, of the children who have a CT scan for minor head injury, approximately 4–7% have an intracranial injury on CT scan and only 0.5% require neurosurgical intervention.Reference Klassen, Reed and Stiell2,Reference Mitchell, Fallat, Raque, Hardwick, Groff and Nagaraj5–Reference Schunk, Rodgerson and Woodward9 In addition, the diagnosis of a small number of intracranial injuries has previously been reported to be delayed or missed.Reference Hamilton, Mrazik and Johnson10

The clinical importance of vomiting in predicting intracranial injury after minor head injury is unclear in children, and the role of recurrent episodes of vomiting is also not well understood. Children presenting to the ED with minor head injury commonly have a history of vomiting,Reference Osmond, Klassen and Wells8,Reference Borland, Cheek and Neutze11,Reference Dayan, Holmes and Atabaki12 and vomiting one or more times has been associated with increased risk for skull fractureReference Nee, Hadfield, Yates and Faragher13 and intracranial injury.Reference Oman, Cooper and Holmes14–Reference Stiell, Wells, Vandemheen, Clement, Lesiuk and Laupacis16 Vomiting ≥ two episodes after minor head injury is associated with increased risk of intracranial injury in adults (>16 years old), and is included in the Canadian CT Head Rule.Reference Stiell, Wells, Vandemheen, Clement, Lesiuk and Laupacis16 Conversely, other research has shown that vomiting is not a strong predictor of intracranial injury in children. Specifically, a meta-analysis of factors predicting intracranial injury after pediatric minor head injury found that, in general, vomiting was not a significant predictor; however, they were unable to comment on the association between recurrent vomiting and intracranial injury.Reference Dunning, Batchelor and Stratford-Smith17 As well, recent research has found that vomiting in isolation of other symptoms in the setting of a reported minor head injury did not predict clinically significant brain injury.Reference Borland, Cheek and Neutze11,Reference Dayan, Holmes and Atabaki12,Reference Kuppermann, Holmes, Dayan, Hoyle, Atabaki and Holubkov18

Vomiting is currently included in the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN)Reference Kuppermann, Holmes, Dayan, Hoyle, Atabaki and Holubkov18 Head Injury Algorithm (any vomiting), and the Children's Head Injury Algorithm for the prediction of Important Clinical Events (CHALICE) (≥ 3 episodes)Reference Dunning, Daly, Lomas, Lecky, Batchelor and Mackway-Jones19; however, it was not included in the original seven-item Canadian Assessment of Tomography for Childhood Head Injury (CATCH) Rule.Reference Osmond, Klassen and Wells8 With further research in a second prospective cohort, the CATCH2 study,Reference Osmond, Klassen and Wells20 aiming to validate and refine the CATCH rule, identified that the addition of “≥4 episodes of vomiting” to the original rule increased the sensitivity of the tool to predict brain injury and need for neurosurgical intervention; therefore, it was included in the rule. Understanding the role of various characteristics of vomiting in the context of possible intracranial injury is important for clinicians as they are using CT decision rules and discussing risk of intracranial injury and need for CT scanning with patients and their families.Reference Hess, Homme and Kharbanda21

The primary objective of this secondary analysis of the CATCH2 study data was to determine the importance of recurrent vomiting in predicting the presence of intracranial injury on CT Head for children 0–16 years of age who present to the ED with minor head injury. Specifically, the study aimed to determine the value of the number and timing of vomiting episodes in predicting intracranial injury.

METHODS

Study design and time period

This was a secondary analysis using data from the CATCH2 study,Reference Osmond, Klassen and Wells20 which was a multicenter prospective cohort study conducted between April 2006 and December 2009. Research Ethics Board approval for the CATCH2 study was obtained from each participating institution, and informed consent was obtained from all participants and guardians. Approval for this secondary analysis was obtained from the University of Manitoba Health Research Ethics Board.

Study setting and population

Participants of the CATCH2 studyReference Osmond, Klassen and Wells20 were children 0 to 16 years old, who presented to one of nine Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) member hospitals participating in the study within 24 hours of a blunt head trauma resulting in a minor head injury. The full CATCH2 methodology with study patient flow diagram was previously published.20 In summary, participants were included if they had a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 13 to 15 after the injury and experienced either loss of consciousness, amnesia, disorientation, persistent vomiting (≥ two episodes, at least 15 minutes apart), or irritability. Children were excluded from the study if the injury was greater than 24 hours from the ED presentation, had previously presented to the ED for the same injury, had evidence of penetrating skull injury or obvious depressed skull fracture, acute focal neurological deficits, history of global developmental delay, or an injury secondary to child abuse.

Study protocol

Emergency staff physicians or senior residents, who underwent a 1-hour training session describing the study and standardized clinical assessments, completed an assessment form that included multiple variables shown in previous research to be associated with head injury, including the seven-item CATCH decision rule (GCS <15 2 hours after injury, suspected open/depressed skull fracture, history of worsening headache, irritability, signs of basal skull fracture, large boggy scalp hematoma, and dangerous mechanism of injury).20 Vomiting-specific variables collected were presence of vomiting, number of episodes of vomiting, length of time after injury to first vomiting episode, and time of vomiting episodes after physician assessment.

After the standardized clinical assessment, physicians ordered a CT scan of the head based on their clinical judgment. The CT scans were interpreted by blinded staff radiologists. Any child who did not undergo a head CT at initial presentation underwent a 14-day postinjury follow-up phone interview by a trained nurse blinded to the child's clinical details. At this time, if the participant was asymptomatic, with absent to mild headache, no memory or concentration problems, no seizure or focal motor findings, and had returned to normal daily activities, they were classified as having no clinically important brain injury. If they remained symptomatic, they were recalled to the ED for reassessment and CT scan. Patients could only be classified as having a brain injury based on their CT findings. Patients who did not undergo a CT scan and could not be reached for the follow-up interview were excluded from the final analysis.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of intracranial injury was defined as any acute intracranial lesion on CT scan attributable to acute trauma, including closed depressed skull fracture, or pneumocephalus. Basilar and nondepressed skull fractures were excluded. Need for neurosurgical intervention was defined as either death secondary to the head injury within 7 days, or the need for craniotomy, skull fracture elevation, intracranial pressure monitoring, or intubation and ventilation for the purpose of treating head injury.

Data analysis

The demographic and clinical characteristics were examined using descriptive statistics. Chi-squared tests for significance were used to compare groups with presence or absence of recurrent vomiting. Recurrent vomiting was defined as ≥ four episodes of vomiting to remain consistent with CATCH 2 criteria.Reference Osmond, Klassen and Wells20 As well, multi-predictor logistic regression was used to determine if vomiting frequency, timing, duration, or isolated vomiting, or age were associated with increased risk for intracranial injury on CT. The multivariable regression included the other CATCH variables that have previously been shown to be associated with increased risk of intracranial injury,Reference Osmond, Klassen and Wells8,Reference Osmond, Klassen and Wells20 including dangerous mechanism of injury, GCS <15 at 2 hours, suspected open or depressed skull fracture, signs of basal skull fracture, worsening headache, irritability, and large boggy scalp hematoma. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported, and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Too few events were observed to permit multi-predictor logistic regression using need for neurosurgical intervention as the outcome. Analyses were performed using R version 3.5.1.22,Reference Wickham23

RESULTS

The CATCH2 study enrolled 4,060 participants, and 4,054 had complete demographic information and were included in this analysis. In total, of the 4,054 participants (mean age 9.19 years; SD 5.12 years), 1,415 (34.9%) underwent a CT head, and 2,643 (65.2%) participants were followed-up by telephone. A total of 464 (11.4%) were younger than 2 years. A total of 197 (4.9%) participants were diagnosed with an acute intracranial injury on CT, and 23 (0.6%) required neurosurgical intervention. Of the 4,054 participants, 2,441 (60.2%) participants had no episodes of vomiting, 85 (2.1%) had 1 episode, 346 (8.5%) had 2 episodes, 327 (8.1%) had 3 episodes, 260 (6.4%) had 4 episodes, 158 (3.9%) had 5 episodes, 159 (3.9%) had 6 episodes, and 278 (6.9%) had 7 to 25 episodes of vomiting. In total, 855(21.1%) experienced recurrent vomiting (i.e., with ≥ four episodes).

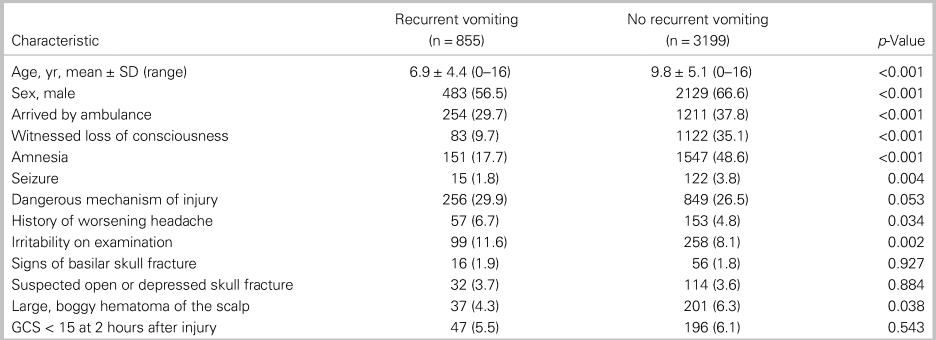

Children with recurrent vomiting were more likely to be younger (6.9 years v. 9.8 years; p < 0.001) and female (43.5% v. 33.4%; p < 0.001), and less likely to have witnessed loss of consciousness (9.7% v. 35.1%; p < 0.001) and amnesia (17.7% v. 48.4%), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of 4,054 children with minor head injury with and without recurrent vomiting in the CATCH2 study

SD = standard deviation; GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale.

Note: Presented as n (% of total) unless otherwise stated, and p-values reported from chi-squared test or two-sample t-test. Recurrent vomiting is defined as ≥ four episodes of vomiting. Dangerous mechanism of injury is defined as motor vehicle crash, fall from elevation ≥ 3 ft or five stairs, or fall from bicycle with no helmet.

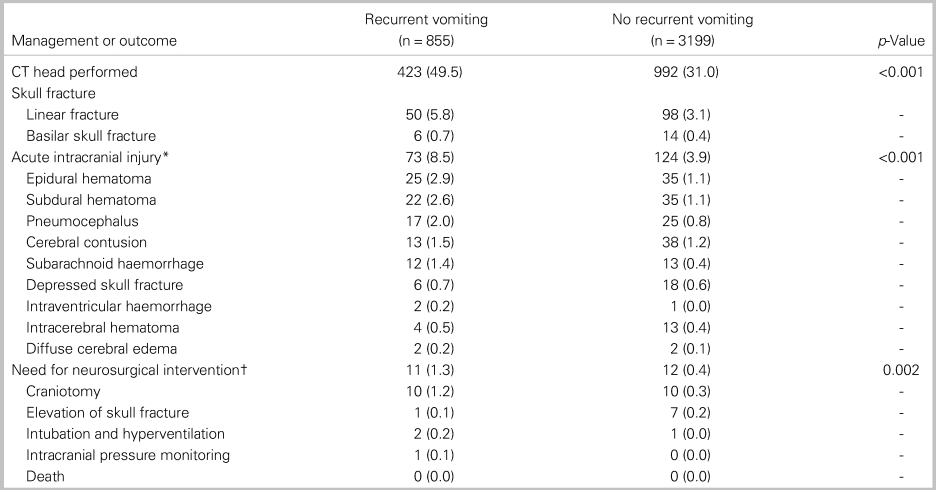

Table 2 shows children with recurrent vomiting were more likely to have a CT head (49.5% v. 31.0%; p < 0.001), more likely to have an intracranial injury on CT scan (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.7–3.1; p < 0.001), and more likely to require neurosurgical intervention (OR, 3.5; 95%CI, 1.5–7.9; p = 0.003.

Table 2. Bivariate associations between those with recurrent vomiting and outcomes in 4,054 children with minor head injury in the CATCH2 study

CT = computed tomography.

Note: Presented as n (% of total) unless otherwise stated, and p-values obtained from chi-squared tests of the aggregated outcomes. Recurrent vomiting is defined as ≥ four episodes of vomiting.

* Some participants had more than one lesion.

† Some participants had more than one intervention.

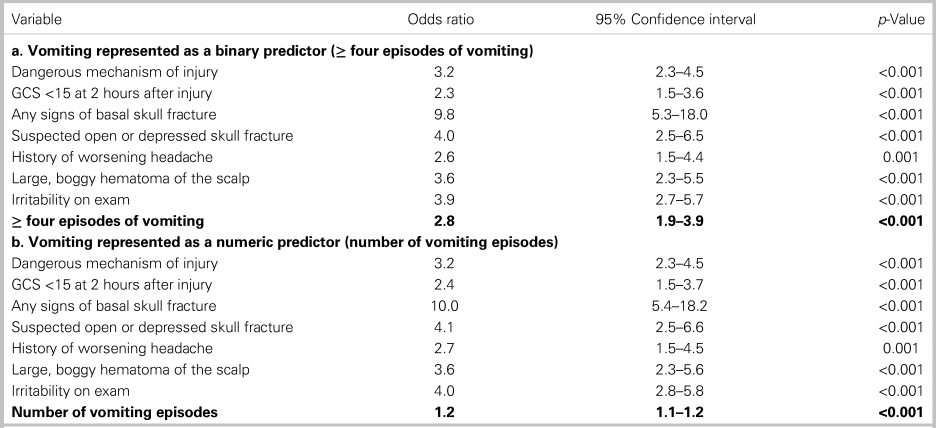

Table 3a shows the multivariate logistic regression model for the CATCH2 variables in predicting intracranial injury on CT head, including the recurrent vomiting (≥ four episodes) variable. With all CATCH2 criteria included, vomiting ≥ four episodes remained a significant factor in predicting intracranial injury.

Table 3. Adjusted odds ratios from the multivariate logistic regression model for CATCH2 criteria predicting intracranial injury on CT Head with vomiting represented as (a) binary and (b) numerical predictors

GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale; CT = computed tomography.

Table 3b shows a multivariate logistic regression model for the CATCH variables with the number of episodes of vomiting as a continuous variable. The odds of having an intracranial injury increased as the number of episodes of vomiting increased when controlling for the other CATCH variables. For each additional episode of vomiting, the odds of an intracranial injury increased by an OR of 1.2.

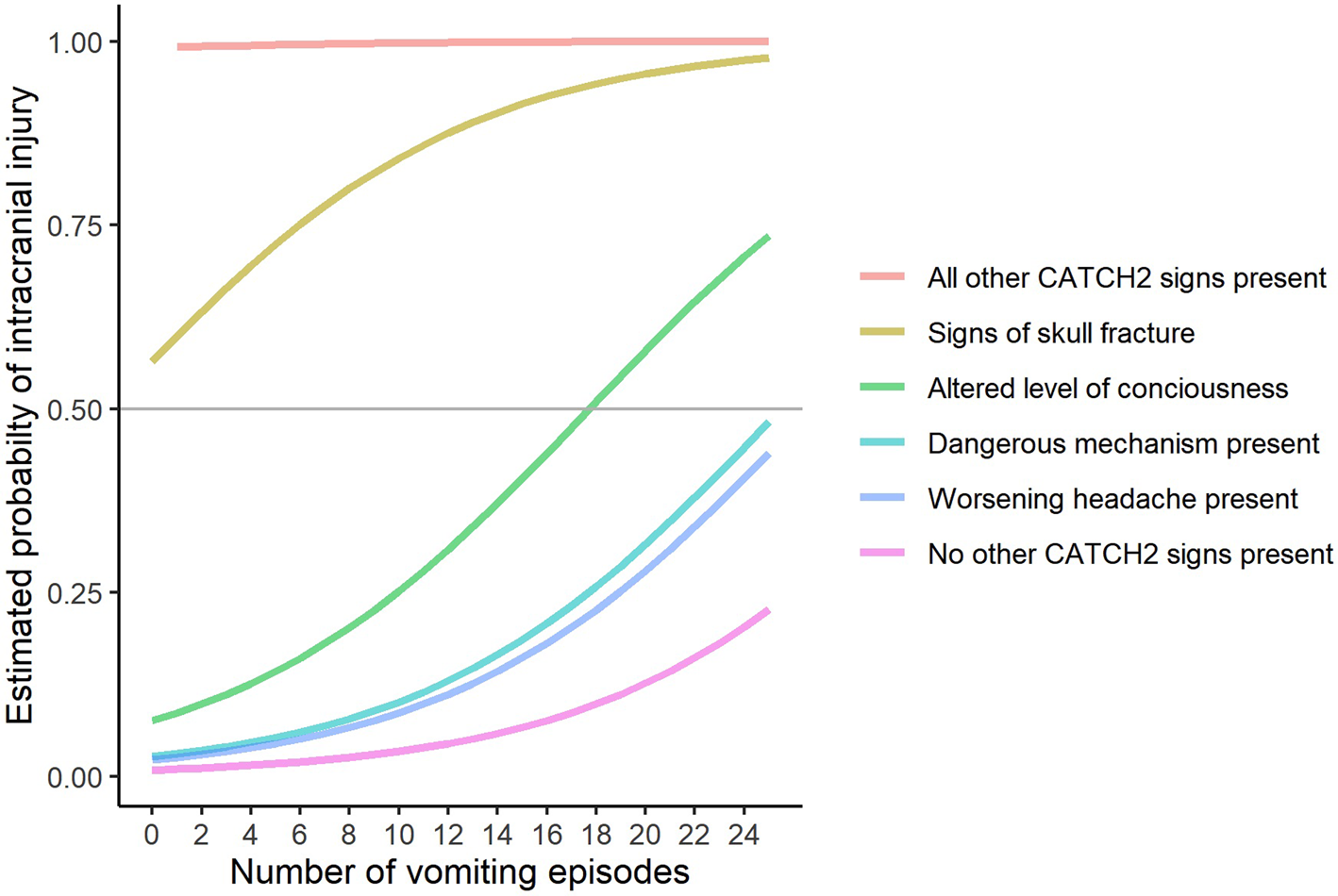

Figure 1 illustrates the predictions from this model in graphic form, showing that as the number of episodes of vomiting increase, the probability of intracranial injury increases; the risk also increases in the presence of the other CATCH2 variables, particularly when signs suggestive of a skull fracture, and altered level of consciousness were present.

Figure 1. An illustration depicting predictions from the logistic regression model described in Table 3b, showing estimated probability of intracranial injury with increasing episodes of vomiting and other CATCH2 factors.

Note: Signs of skull fracture = suspected open or depressed skull fracture + signs basal skull fracture + boggy scalp hematoma, Altered level of consciousness = GCS < 15 at 2 hrs + irritability. The predictions are for hypothetical combinations of symptoms, not for particular groups of patients in the data.

The mean length of time to first episode of vomiting was 1.91 hours and median 1.0 hours (SD, 2.94; range, 0–23 hours). The timing of the first episode of vomiting was not a significant predictor of intracranial injury (OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.94–1.09; p = 0.489) when controlling for the CATCH2 variables.

Age of the child was also not found to be a significant predictor of intracranial injury when combined with vomiting and the other CATCH2 criteria in a multivariate logistic regression model (OR, 1.0; 95% CI, 1.0–1.1; p = 0.581).

Of the 855 children with recurrent vomiting, 459 (11.0%) had vomiting ≥ four episodes as the only CATCH2 symptom present, and of this group, seven (1.5%) had an intracranial injury.

DISCUSSION

Interpretation of findings

The result of this secondary analysis of the CATCH2 data showed that recurrent vomiting was a significant risk factor for intracranial injury in children presenting to the ED after minor head injury. Compared with children with no recurrent vomiting, children with recurrent vomiting were significantly more likely to have a CT head scan performed, have an intracranial injury on CT head scan, and require neurosurgical intervention. Any vomiting after minor head injury was found to significantly increase the risk of an intracranial injury with each additional episode of vomiting further increasing the risk.

The impact of vomiting on the probability of intracranial injury was also much stronger in the presence of other clinical factors. The probability of an intracranial injury increased progressively with the number of vomiting episodes, and the probability increases further with signs of a skull fracture (suspected open or depressed skull fracture, signs of basal skull fracture, and large boggy scalp hematoma), or altered level of consciousness (GCS at 2 hours < 15 and irritability). The probability of intracranial injury also increased, but to a lesser degree, with increasing episodes of vomiting and worsening headache, or dangerous mechanism of injury.

The study also found that both the timing of first vomiting episode and the child's age did not change the risk for intracranial injury. The group of children with recurrent vomiting were significantly younger; however, this was not associated with any change in risk of intracranial injury when controlling for all other CATCH2 factors.

Comparison to previous studies

The results of this study were consistent with findings in the literature. The overall rate of intracranial injury on CT head scan in this study was 4.9%, which is consistent with rates of intracranial injury in the literature.2,5–9 Similar to our findings, Kuppermann et al. also found that any vomiting in a child 2 years of age and older significantly increased the risk of an intracranial injury.Reference Kuppermann, Holmes, Dayan, Hoyle, Atabaki and Holubkov18 Previous research has also shown that the risk of intracranial injury increases when vomiting is combined with other high risk factors. The Australasian Paediatric Head Injury Rule Study found that children with vomiting and either signs of a skull fracture, altered level of consciousness, acting abnormally, or headache, are at an increased risk for a clinically important brain injury.Reference Borland, Cheek and Neutze11 As well, using the PECARN data,Reference Dayan, Holmes and Atabaki12,Reference Kuppermann, Holmes, Dayan, Hoyle, Atabaki and Holubkov18 vomiting accompanied by other concerning clinical findings was identified as putting children at increased risk for a clinically important brain injury. These consistent findings are important for clinicians, as the clinical suspicion for intracranial injury should be very high if the patient presents with multiple episodes of vomiting in the presence of other high-risk factors.

The recent secondary analysis of the PECARN data, found that a clinically important brain injury is uncommon in children with isolated vomiting, and not an independent predictor.Reference Dayan, Holmes and Atabaki12,Reference Kuppermann, Holmes, Dayan, Hoyle, Atabaki and Holubkov18 The Australasian Paediatric Head Injury Rule Study also concluded that isolated vomiting was not an independent predictor of intracranial injury after minor head injury, and suggested that if vomiting is the only symptom a clinically significant brain injury is less likely.Reference Borland, Cheek and Neutze11 Unfortunately, as our study included only symptomatic children with minor head injury, we were unable to comment on the predictive nature of vomiting in complete isolation of other symptoms.

Limitations

There are several potential limitations to this study. First, our study population included only symptomatic children after minor head injury, with vomiting being an inclusion criterion only if there were two or more episodes. As a result, vomiting as an isolated finding is relatively uncommon in our study. As well, CT scans were not performed on all children for ethical reasons of limiting unnecessary radiation. However, these children were all followed-up by a structured, validated phone interview at 14 days to determine if clinically significant brain injury might be present. In addition, the clinical significance of small intracranial injuries seen on CT scan is unclear. The more clinically significant outcome is the need for neurosurgical intervention; however, the sample size was not large enough to permit multi-predictor logistic regression.

Finally, there may be causes for vomiting that are outside of intracranial injury severity. Previous research has indicated that confounding variables, such as personal or family history of motion sickness or migraine, are relevant factors in whether a child will vomit after head trauma.Reference Jan, Camfield, Gordon and Camfield24–Reference Brown, Brown and Beattie26 Due to the use of a previously established data set, however, these variables were not available for analysis.

Clinical implications

This study adds information to the literature to help clinicians determine which patients are at higher risk for intracranial injury and neurosurgical intervention and will require close observation or a CT scan after minor head injury. Based on the study results, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for an intracranial injury when a child presents with recurrent episodes of vomiting. Children with vomiting ≥ four episodes, particularly when associated with signs of a skull fracture or altered level of consciousness, are at a higher risk of having an intracranial injury on CT scan.

Research implications

Further research is needed to determine what confounding factors specifically put children at higher risk of vomiting after minor head injury, such as the history of motion sickness or migraine, and how these relate to the risk of intracranial injury. There is also limited research on the implications of the timing of the first episode of vomiting after injury, and specifically the risk of intracranial injury with late onset vomiting (> 24 hours). Our study suggests that the timing of the first episode of vomiting does not change the risk for intracranial injury; however, children were only enrolled if they presented in the first 24 hours after injury.

CONCLUSION

Recurrent vomiting (≥ four episodes) is a clinically significant risk factor for intracranial injury in children presenting to the emergency department after minor head injury. The probability of an intracranial injury increases with the number of vomiting episodes, and the risk is particularly high if vomiting is accompanied by other high-risk factors, such as signs of a skull fracture or altered level of consciousness.

Research Group Information

Additional members of the Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) Head Injury Research Group are: Kathy Boutis, MD (Department of Pediatrics and Child Health Evaluative Sciences Research Institute Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON); Gary Joubert, MD (Department of Pediatrics, Western University, London, ON); Serge Gouin, MD (Department of Pediatrics, CHU Sainte-Justine, Montreal, QC); Simi Khangura, MD (Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC); Troy Turner, MD (Department of Pediatrics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB) Francois Belanger, MD (Department of Pediatrics, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB); Norm Silver, MD (Department of Pediatrics, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB); Brett Taylor, MD (Department of Pediatrics, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS); Janet Curran PhD (Department of Pediatrics, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS); Jennifer Davidson, RN (Department of Pediatrics, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB); Rhonda Correll, RN (Clinical Research Unit, Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute, Ottawa, ON); George A Wells, PhD (Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON); and Ian G Stiell, MD (Department of Emergency Medicine and Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON).

Acknowledgments

We thank the site research coordinators of PERC whose hard work and dedication made this study possible. We thank My-Linh Tran and Sheryl Domingo for data management. We also thank all the emergency physicians, nurses, and clerks at the study sites who voluntarily assisted with case identification and data collection, and all the site radiologists who interpreted the CT scan images.

Financial support

The CATCH2 study was funded by a peer-reviewed grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR Funding Reference Number: MOP-43911).

Competing interests

None to declare.