INTRODUCTION

Studies characterizing emergency department (ED) use have been largely confined to large urban centers. Rural ED use analysis is underrepresented in the literature, yet offers an interesting look at the fabric of medical services and the service needs in rural communities.

In this study we examine the ED in a unique rural hospital setting in northwest Ontario which services a 385,000 km2 region, where patients are often triaged from remote First Nations community nursing stations before transfer to the hospital ED by air ambulance.

The Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre (SLMHC) is a 60 bed hospital serving 29,000 primarily First Nations patients across 31 remote communities.Reference Walker, Cromarty and Kelly 1

In 2009, regional First Nations leaders identified an “epidemic” of opioid abuse in their communities. 2 In 2016, a state of emergency was declared concerning health status of the population, identifyinghealth inequities and wide gaps in services. 3 Social determinants of health, such as housing and access to clean water, are common deficiencies in the First Nations communities of NW Ontario.Reference Garrick 4 Commentators describe underlying determinants of “colonialization, racism, social exclusion and lack of self-determination” as negatively affecting disparities in the health of Aboriginal peoples.Reference Allan and Smylie 5

In the context of these disparities, mental health and addiction (MHA) issues are significant concerns for the First Nations population in the SLMHC catchment area. First Nation youth experience significantly higher rates of mental health problems and have suicides rates six times the general population. 6 , 7

The main objective of this study was to understand the five-year trend in total ED visits, and diagnoses and disposition of patients. Since the region has experienced a profound increase in opioid use disorder since 2009, we were particularly interested in the volume of MHA patients. 2 , Reference Kanate, Folk and Cirone 8

METHODS

Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre obtained anonymized data for a five-year period (2010-2014) from the Northwest Health Alliance, a health care data collection organization which accessed hospital utilization information from National Ambulatory Care Registration System (NACRS). Ethics approval was granted by Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre Research and Review and Ethics Committee.

Data analysis was completed using SPSS (Version 21, IBM, Armank, NY). Descriptive statistics were completed for sex, age, ED volume, disposition, and primary diagnosis. Diagnosis was completed using ICD-10 codes and grouped into relevant clinical categories. Mental health ICD-10 coded visits were combined with codes for substance abuse, addictions and self-harm ED visits.

RESULTS

From 2010-2014 there were 80,212 ED visits to SLMHC resulting in an annual average of 55 (95% CI 50.2, 59.8) per 100 population. Fifty-four percent of visits were from Sioux Lookout while 41% were from Northern Communities and 5% were from areas outside of the catchment area. People aged 20-40 years made up the majority of visits with those aged 76 and older visiting the least. Women visited the ED more frequently than men: 55% versus 45% of visits.

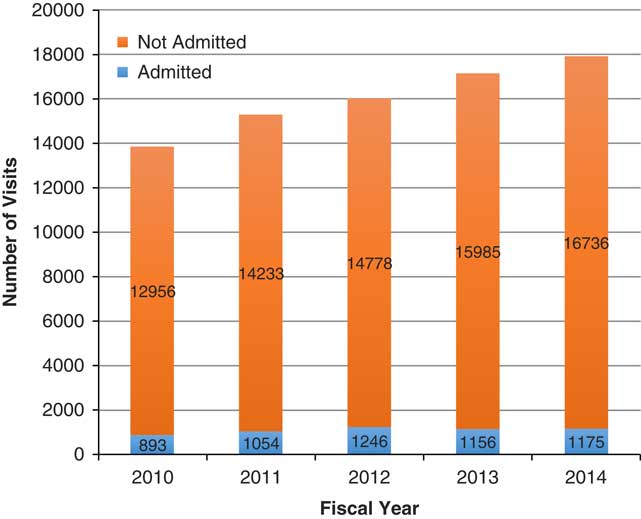

The annual number of ED visits increased 29% from 2010-2014, for a total of 17,911 visits in 2014 (Figure 1). The annual visit rate per capita in 2014 was 62 per 100 population and averaged 55 per 100 over 5 years.

Figure 1 Yearly ED visits with disposition 2010-2014.

Admission rates were stable at 6.9% (95% CI 6.3, 7.5) (Figure 1) and less than 1% of ED patients were transferred on to tertiary care centers.

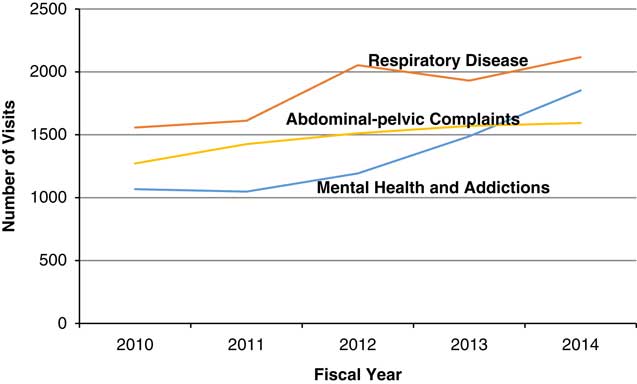

The three commonest diagnostic ED visit categories were respiratory, MHA, and abdominal/pelvic complaints. Our most dramatic finding was the increasing trend in ED visits for MHA, which increased 73% in the 5-year study period (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Three most frequent diagnoses at SLMHC ED 2010-2014.

The ED workload of MHAs incurred significant inpatient service needs, constituting 8.2% of admissions (458/5,552) and 14.7% of transfers (111/755) from 2010-2014.

In 2014 alone, MHA presentations in the ED accounted for 10.3% of ED visits and 8.7% of hospital admissions, and accounted for 20.0% of patient transfers to tertiary care centers or psychiatric facility (Table 1). MHA ED patients were most commonly (59.2%) in the 20-40 age group and demonstrated a slight preponderance of females (51.5%). This same age group also experienced the highest increase (90%) in MHA ED visits during the study period.

Table 1 ED visits, admissions and transfers for SLMHC for 2014

MHA, mental health and addiction

DISCUSSION

Ontario-wide ED visits per capita increased 27% between 1998-2008, when it was measured at 42 per 100 population.Reference Ovens and Chan 9 , 10 This provincial utilization rate is slightly lower than the Canadian average ED utilization of 49 per 100 population. 11 The SLMHC ED visit volume increased a similar rate (29%) in just a 5-year period, without related population increases.

Rural utilization rates are typically higher than urban, given that rural EDs provide both emergency and urgent primary care service.Reference Haggerty, Roberge and Pineault 12 , Reference McCusker, Roberge and Tousignant 13

Our 2014 visit rate of 62 per 100 population (five-year average of 55), was lower than expected for such a large and remote region, and was lower than other rural estimates found in the literatureReference Harris, Bombin and Chi 14 - Reference Vlabaki and Milne 17 (see Table 2). This likely reflects the geographic barrier of distance and access, as 80% of the catchment population reside in remote communities without road access to the hospital EDs. Patients in these communities visit their local nursing station for urgent and emergent care and our hospital data only captured this information when they were triaged and transported to the hospital ED.

Table 2 Estimated ED visits per capita in rural and general populations

Respiratory disease was the most common diagnosis responsible for our ED visits. Canada-wide data from 2014 places respiratory illness as the third most frequent ED diagnosis (behind abdominal/pelvic pain and chest pain). 18 Respiratory conditions are common in our catchment population.

We have previously documented high rates of admission for pneumonia for both infants and adults, likely a result of inadequate and crowded housing in northern communities.Reference McCuskee, Fewer and Kirlew 19 - Reference Muileboom, Hamilton and Kelly 24

In general, respiratory and abdominal-pelvic complaints are common reasons for an ED visit, but MHAs are not in the national top ten common reasons for an ED visit. 18 Our hospital encountered a twelve-fold higher rate of MHA ED visits in 2012 when compared to Ontario-wide numbers and the gap is widening (Table 3).

Table 3 Mental health and addiction (MHA) ED visits per 100,000 population

The leading reason for transfer from our facility was for orthopedic care (21.0% of transfers). This was similar to a southern Ontario rural emergency department study, where 23% of transfers were orthopedic.Reference Rourke and Kennard 15 However, our second leading reason for patient transfer (20.0%) in 2014 was MHAs, while it accounted for only 4.5% of transfers in the southern Ontario study.Reference Rourke and Kennard 15

Our ED visits for MHA diagnoses increased 73% in the 5-year study period (Figure 2). This increase was consistent with the growing epidemic of opioid abuse described by regional First Nations leaders in 2009. 2 Opioid use disorder is additive to a preexisting burden of mental health challenges in the First Nations population. 25 In 2013, the regional maternity program documented 28% of pregnancies experiencing some narcotic exposure during gestation.Reference Kelly, Dooley and Cromarty 26 , Reference Dooley, Dooley and Antone 27 One regional First Nation community documented an adult age adjusted rate of treatment for opioid use disorder of 41%.Reference Kanate, Folk and Cirone 8 Many communities have begun to address addictions.

New community-based addiction treatment programs have been initiated in 22 of the 31 remote communities in the region and hospital-based services have developed to address with the burden of widespread opioid use disorder. 3 , Reference Kiepek, Hancock and Toppozini 28 - Reference Jiwa, Kelly and Pierre-Hansen 32 The community-based programs play an important role in decreasing drug-related “medivacs”. One community with a robust First Nations Healing and opioid agonist treatment program recorded a 30% decrease in such medical transfers.Reference Kanate, Folk and Cirone 8 Positive community changes have resulted from one such community-based addiction treatment programming: school attendance has increased 33% and child protection cases have decreased by 58%.Reference Kanate, Folk and Cirone 8

It may not be surprising that the regional visit rates to the ED for MHAs were orders of magnitude greater than the rest of the province (Table 3). ED visit rates for MHA include visits for intentional self-harm. Public Health Ontario statistics indicate our region has the highest rates of ED visits for self-harm in the province, particularly in youth (age 10-19). 33

Increasing ED visits for mental health and addiction issues indicate that community-based and hospital MHA services need further development to address the scope of the problem. Substantial political, economic, and social changes are needed to address the social determinants of health which propagate an ongoing high burden of MHA issues in NW Ontario.

Limitations

Community nurses provide a substantial amount of primary and urgent care in the remote communities of our ED catchment area and this information is not captured in our study. The remote nursing stations and community MHA workers also locally manage a heavy workload related to MHAs, limiting transfers to the ED.

CONCLUSION

The Sioux Lookout ED provides rural hospital services in a unique hospital and community environment. The dramatic increase in MHA ED visits mirrors the opioid use disorder epidemic the region is presently experiencing. MHA may soon become the most common ED presentation. If reasons for ED visits serve as a proxy for unmet outpatient needs, increased efforts at developing community MHA services and addressing the underlying social determinants of health are required.

Competing Interests: None declared.