Article contents

The Profit-Output Relationship of a Soviet Firm: Comment*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 November 2014

Abstract

- Type

- Notes and Memoranda

- Information

- Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science/Revue canadienne de economiques et science politique , Volume 19 , Issue 4 , November 1953 , pp. 523 - 531

- Copyright

- Copyright © Canadian Political Science Association 1953

Footnotes

I am indebted to Joseph Berliner, James Crutchfield, Neil Field, and Dean Worcester for helpful suggestions.

References

1 Ronimois, H. E., “The Cost-Profit-Output Relationship in a Soviet Industrial Firm,” XVIII, no. 2, 05, 1952, 173–83.Google Scholar

2 This far I am in agreement with him.

3 Cf. Shvedskii, A. E., Otchisleniia ot pribylei gosudarstvennyykh khoziaistvennykh organizatsii i predpriiatii (Deductions from Profits of State Economic Organizations and Enterprises), Moscow, 1948, passim.Google Scholar

4 Berliner, Joseph, “Informal Organization of the Soviet Firm, “Quarterly Journal of Economics, 08, 1952.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

5 Ibid., 348 n. 8; 350–2.

6 Liberman, E. G., O phnirovanii pribyli υ promyshlenností (Planning Industrial Profits), Moscow, 1950, 60.Google Scholar Berliner gives a similar example for automotive transport enterprises (p. 348).

7 Vladimirov, P., “Za rentabel'nuiu raboty predpriiatii” (Toward Profitable Operation of Enterprises), Voprosy ekonomihi, 1948, no. 8, p. 30.Google Scholar

8 The total payroll of the national economy in 1940 was 161 billion rubles.

9 There is a large Soviet literature on the techniques used to pay higher than planned wages and the attempts made by the authorities to prevent such practices. I discuss these in chap, II of Soviet Taxation to be published shortly by the Harvard University Press.

10 Cf., for example, Jasny, N., The Soviet Price System (Stanford, 1951), 84 ff.Google Scholar

11 Gurin, L. E., Analiz i kontrol' raskhodovaniia fondov zarabotnoi phty na mashinostroitel 'nom predpriiatii (Analysis and Control of Expenditures of Wage Fund in Machine-Building Industries) Moscow, 1949, 43.Google Scholar

12 This may be inferred from the shape of his cost curves.

13 Cf. Gosplan, , Narodnoe khoziaistpo SSSR, IV, 416.Google Scholar

14 See alternative hypothesis in IV below.

15 This is rational, as Ronimois indicates, because the rate of profit is not the same for all commodities.

16 This should not be taken to imply that Soviets are not aware of the changing shape of a cost schedule (with respect to output) and that they do not take this into account over the longer run.

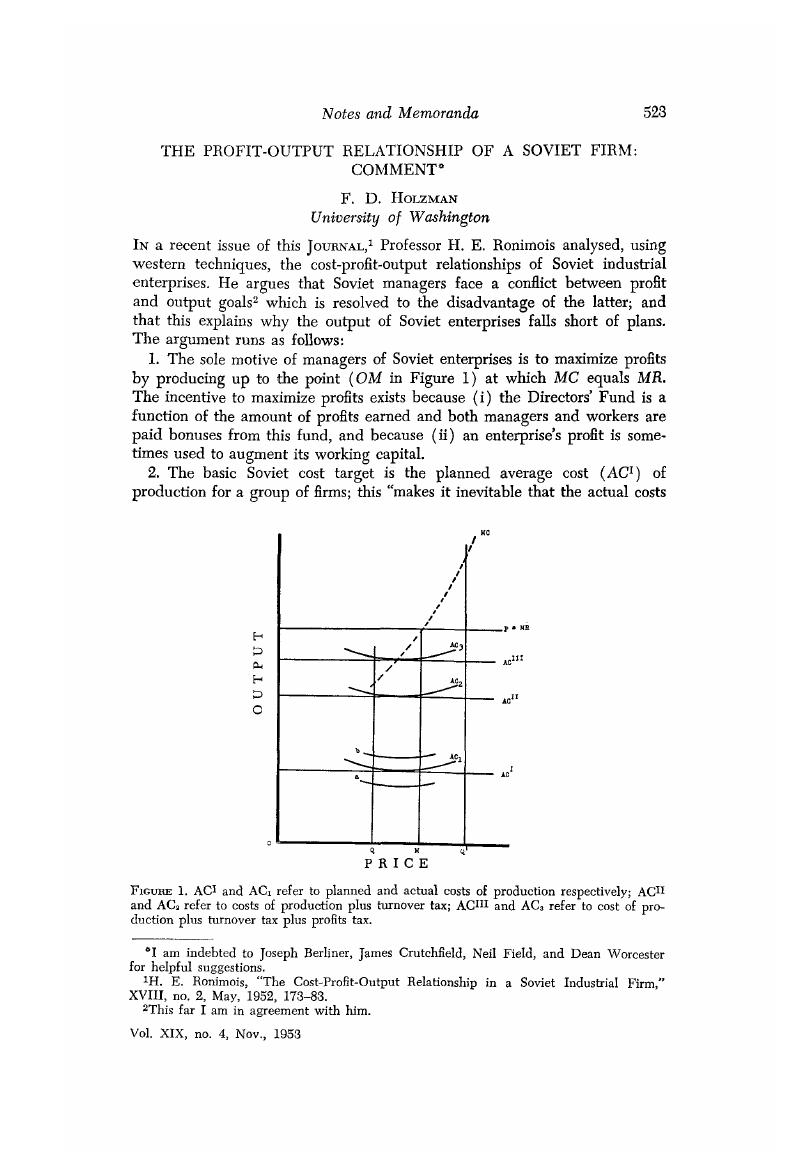

A basic assumption of Ronimois' analysis is that Soviet enterprises typically operate in an “output zone” in which average and marginal costs are rising. This assumption appears to be reasonable not only because of the use of output premia mentioned above (although if Ronimois is correct in assuming that output plans are not usually fulfilled, premia would not often be earned) but because it seems quite probable that Soviet enterprises typically operate at full capacity output. However, since the analysis depends on this assumption, and since this assumption has, in recent years been questioned (e.g., Lester, R. A., “Equilibrium of the Firm,” American Economic Review, 03, 1949, 482)Google Scholar, it should have been made explicit and been discussed.

17 Cf. Turetskii, S. H. “O Khoziaistvennom Raschete” (Economie Accounting), Planovoe Khoziaistvo (Planned Economy), 1939, no. 1, 122 ff.Google Scholar

18 “ ‘The chief fault in the work of industry as a whole was that a number of ministries, which successfully completed the 1947 Plan for gross production, failed to give the assortments demanded by the Plan’ ” (p. 181).

19 His source was not available to me.

20 Batyrev, V. M. ed., Kreditnoe i kassovoe planirovanie (Credit and Cash Planning), Moscow, 1947, 61 ff.Google Scholar

21 Ronimois' entire analysis depends upon the validity of this assertion. Although it is clearly an assumption, no evidence is produced to support it; in fact Ronimois mistakenly states it as a fact, rather than as an assumption (see part II above).

22 Schneider, R. and Shapiro, A., “Fond direktora promyshlennykh predpriiatii” (The Directors' Fund of Industrial Enterprises), Sovetskie finansy (Soviet Finance), 1947 no. 3, 36.Google Scholar

23 It might be argued that production of factor inputs tends to fall below plan for the same reason that final output does, and that factor inputs, therefore, do not tend to be in excess supply. This argument could be true of material inputs, but obviously not of the labour input. And, in fact, the plans for the non-agricultural labour input were substantially overfulfilled in the First and Fourth Five Year Plans, though slightly under-fulfilled in the Second (the Third was interrupted by war). The experience of the First and Fourth plans would suggest that enterprises were not deliberately restricting output.

24 Schwartz, H., Russia's Soviet Economy (New York, 1950), 460.Google Scholar

25 Berliner, , “Informal Organization of the Soviet Firm,” 357–8.Google Scholar Not only scarcity, but break-down of the machinery for directly allocating goods, makes necessary the use of expeditors.

26 With regard to productivity, Ronimois himself says: “A Soviet writer reports that in 1940 as many as 15,000,000 metres of cotton fabrics were not produced because the corresponding amount of cotton was squandered during the production process” (p. 177).

27 This uneven fulfilment was most characteristic of the first two plan periods, and has been somewhat less marked in the post-war years.

- 1

- Cited by