Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 November 2014

1 “Exchange Stabilization in Canada, 1950–4,” this Journal, XXII, no. 2, 05, 1956, 221–33Google Scholar (hereafter referred to as “Stabilization”).

2 Ibid., 221. This argument was based on the analysis of Friedman, Milton, Essays in Positive Economics (Chicago, 1953), 157–203.Google Scholar

3 Friedman, , Essays in Positive Economics, 176 (italics his).Google Scholar

4 In their “Exchange Stabilization Further Considered,” this Journal, XXIII, no. 3, 08, 1957, 404–8 (hereafter referred to as “Stabilization Further Considered”).Google Scholar

5 Kindleberger, C. P., “Exchange Stabilization Further Considered: A Comment,” this Journal, XXIII, no. 3, 08, 1957, 408.Google Scholar

6 “Stabilization Further Considered,” 404.

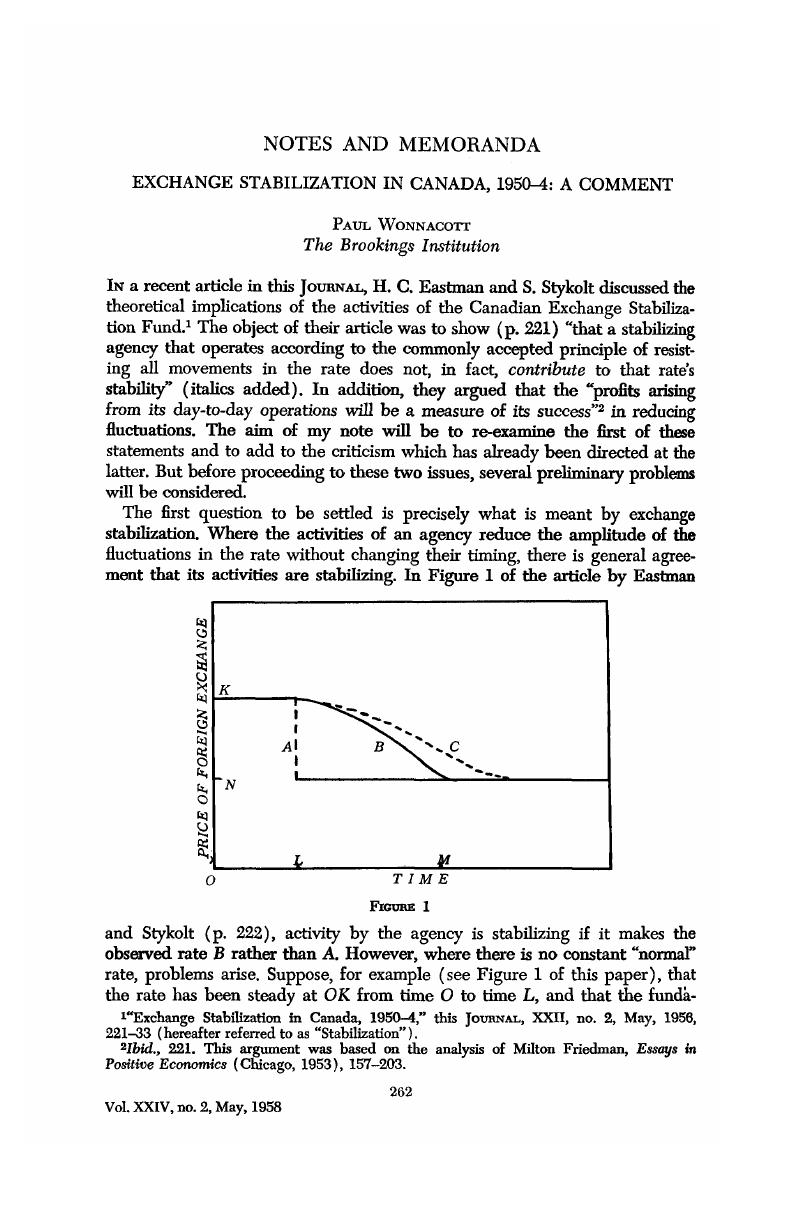

7 The stabilizing effect of a lag in the agency’s response is the basis for a number of statements by Eastman and Stykolt which on first reading appear to be inconsistent with their initial position that resistance to all moves does not contribute to the stability of the exchange rate. For example, they write: “[In resisting all movements], the agency eliminates the very peak and the very trough of each up-and-down movement” (“Stabilization,” 224), and “the effect of its operations on trends is … a slight postponement of the movement through time; a slight reduction of the height of peaks and the depth of troughs; but no significant [?] dampening in the amplitude of the movement” (ibid., 225, italics mine). However, in introducing the stabilizing influence of lags, Eastman and Stykolt have thrown doubt on their position that “Stabilization of a rate of exchange implies knowledge of a normal rate” (ibid., 221).