Introduction

Strong evidence now exists that a biodiversity crisis fuelled by pollution, climate change, invasive species, and overexploitation is upon us (Intergovernmental Science–Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services 2019; Woo-Durand et al. Reference Woo-Durand, Matte, Cuddihy, McGourdji, Venter and Grant2020). Owing to the effects of climate change, living creatures and the bonds that connect them are likewise changing, resulting in stakeholders scrambling to document their existence (Wagner Reference Wagner2020; Woo-Durand et al. Reference Woo-Durand, Matte, Cuddihy, McGourdji, Venter and Grant2020). Arctic and subarctic regions are especially vulnerable to current environmental changes (Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Sato, Ruedy, Lo, Lea and Medina-Elizade2006) and those they will continue to face (Stephenson et al. Reference Stephenson, Smith and Agnew2011). These regions are composed of unique ecological ecosystems; however, their conservation presents a challenge due to a lack of fundamental biological information. Furthermore, research effort is often biased towards charismatic or more harvested species and relatively easily accessible areas. Although some Arctic vertebrates are well studied, many have never been the subject of a published scientific study (Dey et al. Reference Dey, Yurkowski, Schuster, Shiffman and Bittick2018), and this is even more true for invertebrates (Donaldson et al. Reference Donaldson, Burnett, Braun, Suski, Hinch, Cooke and Kerr2016).

Table 1. Definitions of key concepts.

Arthropods of Northern Canada have been scantily studied, and the numerous ecological roles they fulfil in arctic and subarctic regions are not well known (Danks Reference Danks1981; Huffaker et al. Reference Huffaker, Berryman and Turchin1999; Hodkinson Reference Hodkinson2018; Gillespie et al. Reference Gillespie, Alfredsson, Barrio, Bowden, Convey, Culler and Coulson2020). Undoubtedly, this arthropod diversity is essential to ecosystem balance (Hodkinson Reference Hodkinson2018; Gillespie et al. Reference Gillespie, Alfredsson, Barrio, Bowden, Convey, Culler and Coulson2020; Cirtwill et al. Reference Cirtwill, Kaartinen, Rasmussen, Redr, Wirta and Olesen2023) and to humankind’s well-being. For example, pollinators ensure the production of berries that hold cultural significance for Indigenous peoples as a source of food and medicine (Boulanger-Lapointe et al. Reference Boulanger-Lapointe, Henry, Lévesque, Cuerrier, Desrosiers and Gérin-Lajoie2020). Collecting specimens and monitoring their diversity will help us fill in those urgently needed gaps to learn more about their habits and distribution, discover new species, and gain a better understanding of how to protect them.

Standardised biodiversity inventory and monitoring of environmental change in northern regions cannot be done without the collaboration between stakeholders, scientists, organisations, and members of northern communities. Members of northern communities are stewards of nature and partners in its conservation, restoration, and sustainable management, as well as being protectors of Indigenous Knowledge (see definition, Table 1). Indigenous Knowledge systems and practices have been passed on from generation to generation and are crucial to the planet’s future (Dawson et al. Reference Dawson, Coolsaet, Sterling, Loveridge, Gross-Camp, Wongbusarakum and Sangha2021). In Canada’s northern regions, Indigenous leaders are working in collaboration with researchers and governments to restore caribou herds (e.g., Lamb et al. Reference Lamb, Willson, Richter, Owens-Beek, Napoleon and Muir2022) and beluga whale populations (e.g., Breton-Honeyman et al. Reference Breton-Honeyman, Huntington, Basterfield, Campbell, Dicker and Gray2021) whose numbers had been in significant decline.

Community-based participatory research is an approach for all stakeholders to collaboratively monitor biodiversity and partake in decision-making processes. Such programmes are becoming increasingly more rigorous and useful for addressing complex biodiversity conservation and co-management issues (Balazs and Morello-Frosch Reference Balazs and Morello-Frosch2013; Eriksen et al. Reference Eriksen, Rautio, Johnson, Koepke and Rink2021; Drake et al. Reference Drake, Perkovic, Reeve, Alexander, Nguyen and Dunmall2022). Different types of participatory research programmes exist, including social networks of people sharing observations – for example, SIKU, the Indigenous Knowledge Social Network (siku.org), eButterfly (e-butterfly.org), and iNaturalist (inaturalist.org). Some North America-wide programmes focus on a particular species or group of species – for example, Mission Monarch (mission-monarch.org) or Abeilles Citoyennes (abeillescitoyennes.ca) – and some focus on biodiversity in specific regions. The Nunavik Sentinels (espacepourlavie.ca/en/nunavik-sentinels) is one of the latter.

The present paper is the result of contributions by scientists (Amélie Grégoire Taillefer, Maxim Larrivée, Julia Mlynarek, Marjolaine Giroux), members of northern communities, including youth (Haylee Petawabano), professors (Krishna Rodriguez), and organisations (SIKU). In the present paper, we provide an overview of the genesis of the Nunavik Sentinels programme and its benefits to the participants; we describe the structure of the programme (its four pillars and resulting activities), and we present some of the programme’s outcomes and successes to date that broaden our collaborative ties and our understanding of biodiversity north of the fifty-second parallel.

What is the Nunavik Sentinels programme?

The Nunavik Sentinels is a community-based participatory research programme that invites local Indigenous youth to document insect and other arthropod (spiders and myriapods) diversity in northern Canadian territories. The programme is actually deployed in three northern regions: Nunavik, Québec; Eeyou Istchee, Québec; and Nunatsiavut, Newfoundland and Labrador (Fig. 1). Through the programme, members from the Montréal Insectarium – Espace pour la vie work alongside the youth to, at first, introduce them to standardised entomological sampling, observation, collection, and curation. After this introductory training, the youth can choose to act as Sentinels (see definition, Table 1) of their ancestral land.

Figure 1. Map of the three regions where the Nunavik Sentinels programme is deployed: Eeyou Istchee, Québec; Nunavik, Québec, and Nunatsiavut, Newfoundland and Labrador. Communities, national parks, and Canada’s terrestrial ecozones are delimited and located.

Sentinels’ point of view: Testimonial by Haylee Petawabano, 2022 sentinel in the Cree nation of Chisasibi, Eeyou Istchee, Québec

“My role was to collect insect samples in Eeyou Istchee, track my trips through SIKU, label and store each insect sample. These samples were collected to eventually be sent to the Montréal Insectarium at the end of the summer so that the various species could be studied. I also became familiar with properly collecting samples and recognising various species within my hometown, Chisasibi, as well as two other communities in Eeyou Istchee (Waskaganish and Mistissini). I was also given the opportunity to visit the Waapinichikush elementary school to teach students about the distinct species and show them different sampling techniques. It was a wonderful opportunity to show the youth about the unique job opportunities there are in Eeyou Istchee. I was pleased to see the students come out of their shell and show interest in this field of study.

“This project encouraged me to connect with my traditional understandings of the surrounding ecosystems and the environment of Chisasibi, which created a space that encouraged a collective responsibility to effectively respond to climate change. What I took away from this is the importance of centring Indigenous voices by preserving and using our traditional ecological knowledge while also enquiring scientific knowledge and our role in engaging in environmental sustainability. I also want to acknowledge that I do not hold all the traditional teachings like an Elder or a Knowledge Keeper does, but I do believe that I play a role in being the intermediator of both distinct understandings. Being a Biology Technician within my community encouraged me to reconnect with my traditional understanding of the environment of Eeyou Istchee, which I believe is important when conducting any study within the science field. Acknowledging and including Indigenous peoples who occupy the territory is not only essential, but a key factor in revitalising that role that we as Indigenous nations have always cherished as caretakers of our homelands.

“During my participation, I realised that this opportunity shifted my perspective on this field of study. I was not fond of taking the lives of these various insect species. However, I thought of the cause of this project and the beneficial impact it will have on discovering effective ways to fight climate change. I was always taught to set my intentions and thank both animate and inanimate objects whether I was engaging in cultural activities or in this case, gathering insects for science. Every insect sample I collected, I recognised them as important components for our surrounding ecosystems. I began to understand my role as an environmental activist and as an Indigenous woman. The importance of using our traditional ecological knowledge to collaborate with western scientific knowledge helps to combat and adapt to these inevitable environmental conditions that are crucial for our future. The more Indigenous people participate in projects like these, the more change we will begin to see on a global level because we have carried these knowledge and spiritual connections to our homelands since time immemorial.”

Programme genesis

The Nunavik Sentinels is a programme that has been in development for 13 years. The idea for a programme to document insects and other arthropods, especially butterflies and pollinators, in the unique environment of Nunavik (Fig. 1), Québec, Canada, began with Maxim Larrivée, the Director of the Montréal Insectarium, in 2010 (Fig. 2). The programme became a reality when, in 2014, Élise Rioux-Paquette (Kativik Regional Government, Nunavik) asked Maxim to help inventory the insect diversity in Nunavik national parks. From 2015 to 2018, the inventories were coupled with week-long scientific land camps for youth between 12 and 18 years old that were organised by the Kativik Regional Government in different national parks. In sharing these experiences with Inuit and Cree youth, it quickly became clear to the organisers that many of the youth have a predisposition and an enthusiastic interest in entomology and that they have an eye for detail. The youth were also very much engaged with activities that encouraged a relationship with the natural environment around them and showed great respect for all living creatures (Ferreira et al. Reference Ferreira, Cuerrier, Giroux and Norton2018; Grégoire Taillefer et al. Reference Grégoire Taillefer, Giroux and Larrivée2021). What’s more, they are keenly aware that their surroundings are rapidly changing and that climate change is having a major impact on their living environment. However, it was also quickly realised that these youth have little knowledge of the insects and other arthropods of their region and had few to no opportunities to capture and conserve them. This, coupled with the fact that the Canadian North is huge as a territory to be inventoried and the period of insect activity is very short, was the impetus to bring the Nunavik Sentinels programme into existence. In 2019, Amélie Grégoire Taillefer (A.G.T.) was hired as the programme coordinator and to pilot a project to provide initial training to a group of a dozen youth in Pingualuit National Park (near Kangiqsujuaq, Nunavik, Québec; Figs. 1–3) in collaboration with the Kativik Regional Government. The youth were invited to help A.G.T. structure and adapt the training to suit their needs based on their experience in the field. Reference tools (e.g., entomological guides, identification keys, standardised collecting protocol, a trainer’s guide, and a turnkey educational kit; contact the lead author for details) specific to the northern insect fauna and the reality of the northern environment were also created to allow the participants to hone their skills in entomology and adapt them to their interests. The programme has grown considerably and, since 2022, consists of four pillars: (1) training land camp, (2) summer employment, (3) educational kit, and (4) research.

Figure 2. Developmental and implementation timeline of the Nunavik Sentinels programme.

Figure 3. Images from the Nunavik Sentinels programme. Top left: Pingualuit National Park landscape © Espace pour la vie (Maxim Larrivée); top right: learning to sweep © Espace pour la vie (Amélie Grégoire Taillefer); bottom left: incidental capture of the transverse lady beetle in Chisasibi in 2022 © Espace pour la vie (Amélie Grégoire Taillefer); bottom middle: practising pinning specimens © Espace pour la vie (Maxim Larrivée); bottom right: identification in the field in Chisasibi © Espace pour la vie (Amélie Grégoire Taillefer).

The programme’s four pillars

Pillar 1: Training land camp

The first pillar consists of a one-week training land camp offered to groups of a dozen youth as young as 12 years old. The training land camps occur in two ways: (1) the training is provided alongside already existing scientific land camps taking place in the North, where youth learn both from elders and community members about traditional activities on the land and external researchers about other scientific disciplines, or (2) land camps are organised specifically to collect arthropods when local communities invite us.

Youth are introduced, during the peak insect activity period, to different aspects of entomology (Fig. 3) by participating in field expeditions. There is usually one instructor per five or six youths during these field expeditions. This number ensures that everybody stays motivated and interested. The training sessions focus on fieldwork and collection techniques because that is what everybody likes best. During this time, the youth are introduced to the sampling protocol, developed in 2019, so that sampling effort is comparable from year to year, and are shown how to use the SIKU app (see the description in the Standardised collection protocols section, below) to track their findings.

The training sessions are supported by guides and tools that have been developed specifically for this programme and that are language adapted as much as possible to the participants’ mother tongue, with examples provided that relate to their culture. During the land camps, the youth learn about the scientific method, insect morphology, insect ecological roles, the use of identification keys, and proper collection curation techniques.

This first pillar becomes the stepping stone to building collaborations and ensures self-determination this we hope will make this programme meaningful to communities: it provides a way to fully protect their northern natural resources (Hayward et al. Reference Hayward, Sjoblom, Sinclair and Cidro2021; Government of Canada 2022a). The tools and activities are adapted to suit the local reality through an appreciative education approach (Bloom et al. Reference Bloom, Hutson, He and Konkle2013). The translation of reference documents into the Indigenous language of the local community where the activities are engaged helps to ensure community ownership of the discipline in the years to come.

Pillar 2: Summer employment

The second pillar consists of summer employment. Interested youth, aged 15 to 30 years to comply with the Canada Summer Jobs grant requirements, have the opportunity to be hired by the Montréal Insectarium and paid a competitive salary to participate in insect monitoring in their own communities. The opportunity provides Indigenous youth with experience and a stepping stone to future studies or employment. Youth are recruited by different means: (1) the job offer is posted in local job centres, Facebook groups specific to each community, and in schools, community centres, and town halls; (2) academic advisors and teachers at the local high school can recommend the programme to youth who are interested in science; and (3) people involved in the community refer motivated youth to the programme. Youth can apply for the job in different ways: they can send in their resumé, fill an application form, or send an audio/video capsule. They also must prepare for an informal interview, apply for a social insurance number, and open a bank account to receive their pay. If needed, the programme coordinator helps young navigate the process. No experience is needed to apply to become a Sentinel: the youth will receive personalised training and work alongside a member of the Montréal Insectarium at the beginning of the summer. The programme provides youth with an opportunity to make a significant contribution to knowledge about the insect fauna of their ancestral lands and may encourage some to pursue studies in the natural sciences. It also gives those who may not have had the means or chance to go out on the land an opportunity to learn about their environment while learning about science.

Pillar 3: Educational kit

The third pillar is educational and is aimed at northern schools and science land camps. It takes classrooms outside, starting in Grade 6. This pillar was created in 2021 at the request of two teachers from the villages of Inukjuak, Nunavik and Chisasibi, Eeyou Istchee (Fig. 1), Québec, who were interested in developing discovery activities that focused on nature and entomology. The kit is complete and ready for immediate use, and it integrates the discovery of nature, insects, and other arthropods into school or camp curricula.

The kit’s educational documents and tools are reviewed continuously to include objectives that are related to education, research, and community goals. Teachers, educators, and the students taking part in this component receive personalised adapted tools for their activities and a follow-up from the programme coordinator in terms of support for their insect-related activities and help with identification of their discoveries. The educators can use the kit themselves or receive visits from an Insectarium member at the school or camp. The youth become budding entomologists for the days spent outside using the kit.

Pillar 4: Research

The fourth pillar consists of compiling and analysing the data collected through the other pillars – information collected by the Sentinels and the instructors during the training land camps, as well photo observations shared on SIKU by programme participants and other community members. The research compilation and analysis are collaborative efforts undertaken with the communities because the research increases the knowledge of the entomological fauna of the North for everybody involved in the programme. The analysis allows scientists and members in communities to determine the distribution of species, discover new species, and identify the environmental phenomena associated with changes in entomological biodiversity in the face of climate change. Data are analysed by researchers at the Montréal Insectarium, at community-based research centres, or at a combination of both, depending on the agreement in place with the local community. The data and results are also shared with participants, collaborators, and local governments. Specimens collected are also either integrated into the Insectarium scientific collection or returned to the northern communities where they were sampled.

Standardised collecting protocol

The collecting method, which is supplemented by videos and documents, is simple and easy to use. As the primary focus has been on Lepidoptera and other pollinators, the scientific protocol includes active netting in the field and the installation of different-coloured pan traps (called “bee bowls” within the programme) placed along a linear transect. At the beginning of the summer, the programme coordinator or another member of the Insectarium provides an in-person training session in the community of the hired Sentinel. The Sentinel and the trainer choose one or two sampling sites that are easily accessible by foot and are open with little tree or shrub cover for approximately 3000 m2. The habitat should be open so that insects can see the pan traps. The Sentinel learns how to handle live insects, preserve them, prepare collecting labels, prepare equipment for the field, and handle a net. The eight-week sampling period starts about one week after the snow melts – from mid-June to late June in subarctic and Arctic regions – and ends around 15 August. This is the peak activity period for many insects in these regions. The Sentinel net-samples three or four times each week to collect primarily pollinators such as butterflies, bumble bees, wasps, and flies. Each net-sampling event lasts 60 minutes and covers approximately 1000–2000 m in walking distance. The participants are invited to visit as many microhabitats and nectar sources as possible on one sampling site. The insect-handling time – placing insects in envelopes or in jars – is not included as part of the inventory duration. After each sampling event, insects collected in envelopes and jars are placed in a freezer until they are sent back to the Montréal Insectarium for identification.

Collecting with pan traps is done twice each week. Thirty traps (10 each of three colours: white, yellow, and blue) are placed 5 m apart along a straight-line transect, alternating blue, yellow, and white, for a total of 150 m total length. Each 30-mL (12-oz) plastic pan trap is filled halfway with water amended with a few drops of dish detergent to break the surface tension. The traps are left for about 24 hours. After this period, insects are transferred with entomological forceps into 8-mL vials filled with propylene glycol preservative. Propylene glycol is used because it is nontoxic and considered safe for transport on airplanes.

The Sentinels use the SIKU application (siku.org) to archive trip and sampling information. The SIKU platform was developed by the Arctic Eider Society charity, in collaboration with various Inuit community and regional organisations. It is available as both a mobile application – available for free on Google Play (play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=org.siku.siku&hl=en_US) and the Google App Store (apps.apple.com/us/app/siku/id1446633943) – and a web platform and was created to facilitate self-determination in research, education, and stewardship for Indigenous communities. Ice conditions, the presence of animals and insects, and how to track them, their habitat, diet, and physical condition are documented on SIKU. The application supports multiple languages and dialects, enabling users to search in their own dialects for the species they are tagging. SIKU is designed to be responsive to the priorities and needs of its users, so we worked with the SIKU team to develop an insect component on the app that is linked to the Nunavik Sentinels programme, allowing youth attending the programme’s training, Sentinels, and any other interested person in the communities to add their observations of insects in the North. A total of 24 insect and spider profiles that are commonly present in the North were created and added to the platform in 2020. Insect collection tools were added in 2022, allowing Sentinels to archive their work when using nets and pan trap and to share their discoveries with their community, other northern communities, the programme, and the Insectarium. The insect trap post-type allows users to record the site’s geographic position system-derived location information and specific sampling information to track the data, including which data correspond to each deployment.

The collected insects and other arthropods are sent to the Montréal Insectarium, where they are mounted and identified during the off season by museum staff. Along with the Sentinels’ samples, SIKU insect observation and tool posts are used as scientific data and for monitoring because they are automatically geotagged and time-stamped, providing accurate information about trap location, deployment, and retrieval. Being able to tag multiple insects in a single post enables more precise records, and SIKU makes it easy to export and manage the data from these posts. Using the project framework on SIKU, many collaborators can contribute to monitoring insects, and ongoing project collection activities are shared as posts in near-real time with other northern community members, thereby increasing awareness of the project. An annual activity report is sent to every participating community each winter.

Once analysed, the results are shared openly with communities in a variety of ways: during in-person meetings with Northern Village representatives, governments, and participating organisations; via presentations to the community; in scientific and outreach articles in local media; through local radio and television interviews; in publications on our Facebook page and on communities’ Facebook pages; and through scientific posters, “fun facts” sheets about insects, and blogs. On the SIKU platform, insect observations are identified and results are shared through social posts and press releases.

A successful programme

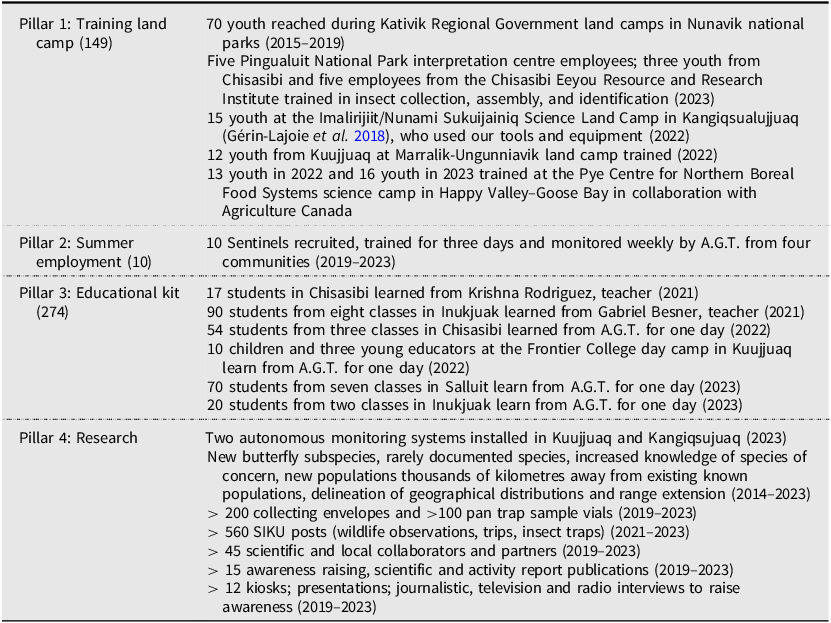

Measuring the success of a programme such as the Nunavik Sentinels is difficult, but the programme and its reputation have grown (Table 2) in terms of the number of communities and youth reached. We say this because Facebook page subscribers and hits are continually increasing, stakeholder interest is always increasing, collaborations continue to evolve and be renewed – despite some activities being curtailed or postponed during the COVID-19 pandemic. This growth in interest tells us that the programme is becoming firmly established and welcome in Nunavik communities and in other northern regions, such as Eeyou Istchee and Nunatsiavut (Fig. 1).

Table 2. Sentinel programme highlights, 2014–2023.

The programme is recognised on the SIKU platform, and anyone interested in insects and other arthropods can contribute to the collection of data on northern arthropod populations. Insectarium staff were invited to provide new tools to school teachers and educators through an educational kit and visit classes and day camps, to train employees of organisations such as the Pingualuit interpretation centre and the Chisasibi Eeyou Resource and Research Institute. Finally, the number of Sentinels is increasing, from one in one community in 2019, to two in one community in 2020 and 2021, to two in two communities in 2022, and to five in three communities in 2023.

After the first five years of expeditions and follow-ups with Inuit and Cree youth in Nunavik national parks in collaboration with Kativik Regional Government, the programme has reached approximately 70 youth (Fig. 2). When the programme officially started in 2019, the first summer employment (pillar 2) took place in the northern village of Kuujjuaq, Nunavik, Québec within the framework of the Canada Summer Jobs grant programme (a Canadian government programme for 15- to 30-year-olds). Siaja Parceaud-May, a 28-year-old amateur entomologist, was hired for eight weeks to collect in and around her community. She was provided with in-person training and follow-up. Since it was not possible to travel to Nunavik in 2020 and 2021, one of us (A.G.T.) trained the Sentinels remotely, creating videos to show the collection techniques and sending the methodology and additional explanations before the field season began. In 2020, Siaja was hired for a second consecutive year and mentored Sean Nashak, our second 16-year-old Sentinel in Kuujjuaq. They again sampled for eight weeks. In 2021, Sean Nashak was in his second consecutive year and mentored our third 16-year-old Sentinel, Aputi Unatweenuk. They collected for six weeks in Kuujjuaq. They were also provided with personalised training in the use of the SIKU app by the Arctic Eider Society stewardship coordinator. In 2022, Robert Munick, a 15-year-old student, was hired for eight weeks in Kuujjuaq. He was trained in-person, and a follow-up visit in his community took place in July. We also hired Haylee Petawabano, a 22-year-old student in Native Studies and Biology, as our first Sentinel in Chisasibi, Eeyou Istchee in 2022. In 2023, five Sentinels in three communities were hired for 5–8 weeks each, depending on their availability; these five Sentinels were Allison St-Cyr, a 15-year-old student, and Tony Anautak, 19 years old, in Inukjuak; Destiny Watkin, 28 years old in Kuujjuaq; Robert Andersen, 16 years old, and Olsen Nochasak Ford, 16 years old, in Makkovik, Nunatsiavut, Newfoundland, and Labrador (Fig. 1). After the initial field training, the coordinator virtually checked in weekly with the Sentinels through phone calls, Microsoft Messenger, emails, and the SIKU platform to ensure a smooth and problem-free experience. One objective for the coming years would be to hire a coordinator who is based in the North to assure in-person follow-ups, deployment in new communities, and local training.

At the request of teachers from Chisasibi and Inukjuak, a pilot educational kit (pillar 3) was deployed in 2021. Since then, the kits have been used approximately by 270 youth in several communities (Fig. 3). The training land camps (pillar 1) reached approximately 150 youth (Table 2).

Testimonial by Krishna Rodriguez, Cree School Board teacher, Chisasibi, Eeyou Istchee, Québec

“I used to be a workaholic, always running from one job to the next; on my walls I had giant white boards filled up with hourly, weekly, monthly, and yearly objectives. One day, I was in my backyard, in Mexico, taking a few minutes to eat a sandwich, when I noticed hundreds of ants walking on a line carrying food crumbs; I followed their path all the way up to a tree. I was so absorbed by their perilous journey that I forgot the madness of my day. Unexpectedly, I found calmness and even joy while observing those ants; somehow all the craziness of my daily life seemed meaningless. I was hooked! I discovered that day that staring at insects grounded me. And so my life was never the same, I slowly started making daily changes; some small, some big; in short, enough of them to drive me into a completely new calling in Chisasibi, Québec.

“In the winter of 2021, I was looking for a project to tackle with my Grade 6 students, a project to cover English and Science that would also help us create a bond. I used to search for ideas on the Internet, but also I used to look at pictures of bugs just to relax at night. And so one day on my Facebook wall, I got a message saying, ‘You might be interested in this.’ I clicked on it, and it was an ad talking about Nunavik Sentinels. I read it, and it was indeed exactly what I was looking for, so I contacted them without hesitation to ask how my class could get involved. Amélie answered all my questions, and we started collaborating on and off because of COVID-19, but in 2022, I integrated Nunavik Sentinels into the curriculum, and it was a perfect project for the following reasons:

It gave us a focused purpose to explore our local environment. My students and I went on many hikes that helped us build a strong bond, some kids liked them, some didn’t, but they always enjoyed the slide show with all the pictures after our walks. By the way, some of the students who didn’t enjoy it are in high school now, and they told me a couple of weeks ago that they miss our hikes.

It made students aware of their own environment, the importance and purpose of insects, and their impact in the local ecosystem.

Students became more sensitive towards the insects and less inclined to kill them as soon as they saw them.

Students started to be aware that what happens up North can affect other parts of the province, country, and the world and that people are interested in different aspects of life in the North. They noticed this when they saw how our pictures and hikes were being published on different media sources.

There was amazing support by Amélie. She would look at the pictures that we sent to her after our hikes, she named the insects, and shared some facts about them. She also shared resources, activity sheets, and informational videos. As a teacher, all of that support by a passionate expert was precious!

“I hope this project will continue to grow so more people can see the value and young people can learn more about the fascinating world of insects.’’

The Montréal Insectarium staff always return from their visits up North enlightened. Depending on where they visit, they can become immersed in Inuit and Cree cultures. They discover and learn a different relationship with the environment and learn to follow Nature’s rhythms. They have a newfound respect and appreciation for the knowledge these northern communities have about the environment, living things, and the interconnectedness of nature.

The Nunavik Sentinels programme’s goals for 2026 are even more ambitious. We hope the programme reaches 450 youth in 10 communities. We intend to hire at least 20 Sentinels. We wish to expand our educational activities to include 394 school students and 36 youth camp participants in three communities (Fig. 2).

Scientific discoveries

Species discovery

Our Sentinels have focused on collecting Lepidoptera and other pollinators in the past years. As a result, their scientific discoveries fall mostly within those taxonomic groups. Several notable discoveries have already been made in collaboration with Inuit and Cree collaborators.

The discovery of the first population of Colias tyche (Bober) (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) in Kuujjuaq is of particular interest because it represents a 1000-km extension of its range and a first record in the continental Arctic east of Hudson Bay. The closest populations of C. tyche are reported from Coral Harbour, Southampton Island, Nunavut, Canada. This Kuujjuaq discovery will also lead to the description of a new subspecies, as Colias tyche siaja, named after our first Sentinel, Siaja Parceaud-May, who sampled the first specimen in June 2019 at the end of Ippialuk road on a large glacial-till ridge.

Another species, Xestia staudingeri (Möschler) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), was also collected for the first time in Québec. This is only the fifth-documented record for this species. It was collected with the Freija Fritillary butterfly subspecies Boloria freija tarquinius (Curtis) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) along the Puvirnituq River in Pingualuit National Park. The larvae of the latter subspecies hibernate twice; adults of this subspecies are therefore found once every two years.

The collection of the Ross’ tussock moth, Gynaephora rossii (Curtis) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae), at Pingualuit and Kuururjuaq National Parks represents the third and fourth locations where this species has been recorded in Québec and confirms its presence in Nunavik.

Caterpillars of Arctia opulenta (Edwards) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) were collected fairly frequently in the alpine tundra. These larvae take two years to develop (Wagner Reference Wagner and Conner2009), and adults may be rare or absent every other year. The caterpillar of this species is commonly named “woolly bear” because of its behavioural, physiological, and structural adaptations to successfully maximise heat gain in northern environments (Kevan et al. Reference Kevan, Jensen and Shorthouse1982).

Chequered skipper or Arctic skipper, Carterocephalus palaemon (Pallas) (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae), and the Dorcas copper, Lycaena dorcas Kirby (Lepidoptera: Pieridae), butterflies were found in Kuururjuaq, which increases their known northern distribution limit by more than 400 km.

Two additional notable mentions are a lady beetle and a fly. The transverse lady beetle, Coccinella transversoguttata Fabricius (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), was incidentally captured by youth at Waapinichikush Elementary School in 2022 (Fig. 3). They were running around armed with nets and magnifying glasses, lifting rocks, and catching all sorts of creatures when a young girl brought back a nice-looking ladybug. Thus was a species of special concern discovered accidentally! The last mention of this species in Eeyou Istchee dates from between 1996 and 2005 (Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada 2016). Botflies, or warble flies, of the genus Hypoderma Latreille (Diptera: Oestridae) were collected by youth in 2019. These flies are common in Nunavik but are rarely documented. Their larvae are internal parasites of mammals and are commonly found in caribou flesh.

Testing monitoring techniques

This programme is also becoming an effective way to test new methods. A nonlethal approach for standardised and global autonomous monitoring of insects assisted by artificial intelligence was tested in summer 2023 by programme participants and local collaborators. Two machines were installed and monitored by wardens at the Pingualuit National Park interpretation centre in Kangiqsujuaq and by the Nunavik Parks, Kativik Regional Government team in Kuujjuaq. Conventional monitoring methods for trapping and identification are time-consuming and expensive, especially in northern environments. Automation would significantly improve biodiversity monitoring.

Conclusion

Since its inception in 2014, approximately 430 youth have been involved with the Nunavik Sentinels programme (Table 2). The programme continues to grow and expand in the North, despite some activities being stopped or postponed due to the pandemic. An increasing number of subscribers follow the programme Facebook page, stakeholders continue to show interest, and continued and new collaborative activities are being developed. This tells us that the programme, supported by its four-pillar approach, is welcomed by Nunavik communities and in other northern Canadian regions such as Eeyou Istchee and Nunatsiavut.

The socio-economic, scientific, and personal benefits of the Nunavik Sentinels programme help everybody involved. Sentinels employed during the summer are prepared for the future job market. The programme allows Sentinels to contribute to the understanding of the natural history of their land. Student and land camp participants become budding entomologists, even if only for a day, and make scientific discoveries not considered likely or possible before. The Sentinels and the students are becoming informal knowledge keepers within their communities. As seen in the testimonials noted in the present paper, the Nunavik Sentinels and other programme participants become drivers of entomological knowledge in the northern regions that host the programme. Montréal Insectarium staff who travel north to work with the students and Sentinels return enlightened: they not only discover different cultures and territories but return with stories about the passion of the peoples in northern communities for nature and their relationship with the environment.

The programme continues to develop entomological education tools to increase youth interest in insects and arthropods. With feedback from participants, new tools (guides, identification keys, field and class activities, etc.) are being finalised. In addition, the programme is recognised on the SIKU platform, allowing anyone interested in insects and other arthropods to contribute data on northern arthropod populations. New monitoring techniques, such as automated monitoring, are also being tested: the programme is facilitating the development of new techniques that may be used in other regions of the world.

There is currently an ongoing promotional campaign to reach all communities in Québec’s north, with the intention of expanding the programme throughout Nunavik. Additionally, new funding opportunities are being sought to ensure the programme continues for several more years. The partnership between the Sentinels, the Insectarium staff, stakeholders, and members of northern communities that is facilitated by the Nunavik Sentinels programme will continue, we hope, to help fill the gaps in the knowledge that northern communities need to preserve their land.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank, at the Kativik Regional Government, Elise Rioux-Paquette for her dedication in making this project happen and Patrick Maltais and Isabeau Pratte for their support and expertise. The authors thank the Arctic Eider Society, especially Billy Nicoll, Joel Heath, and Kassina Ryder, for adding insects and the project on the SIKU platform and contributing to this article. They thank the communities of Kuujjuaq, Inukjuak, Tasiujaq, Salluit, Kangiqsujuaq, Kangiqsualujjuaq, Chisasibi, and Makkovik for their participation. They thank all the project collaborators and participants for their involvement and interest in the programme: the dedicated Sentinels Siaja Parceaud-May, Sean Nashak, Aputi Unatweenuk, Robert Munick, Tony Anautak, Allison St-Cyr, Destiny Watkin, Olsen Nochasak Ford, and Robert Andersen; Mary Pilurtuut and her team at the Pingualuit National Park interpretation centre; teachers Krishna Rodriguez, Ariane Lebel, Isabelle Guertin, Christine Crochet, Gabriel Besner, Caroline Martin, and Eugene Henri Koulla; Mikhaela Neelin and the camp organisers at the Nunavik Hunting, Fishing and Trapping Association; Gregor Gilbert and Adamie Delisle-Alaku at Makivvik Corporation; Erica Oberndorfer, Sean McCann, and Carolyn Parsons at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada; José Gérin-Lajoie and Geneviève Dubois at l’Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières; youth from the Nunami Sukuijainiq 2022 marine land camp; Frontier College and young participants from Kuujjuaq; youth from Marralik-Ungunniavik land camp 2022; youth and organisers of the Pye Centre for Northern Boreal Food Systems camp; the Nunatsiavut Government and the Labrador Inuit Lands. The authors thank Robert LeBrun for the creation of the map of the three regions where our programme is currently deployed. They also thank Julie Jodoin, director of Espace pour la vie and the Insectarium’s public programme and education division for supporting this programme. This project was generously funded by RioTinto and RBC through the Espace pour la vie Foundation. The salary of the Sentinels was supported in part by the Canada Summer Jobs programme. Airplane tickets were supported in part by Air Inuit and Canadian North.

Authors contribution

All authors contributed equally to the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.