No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 December 2009

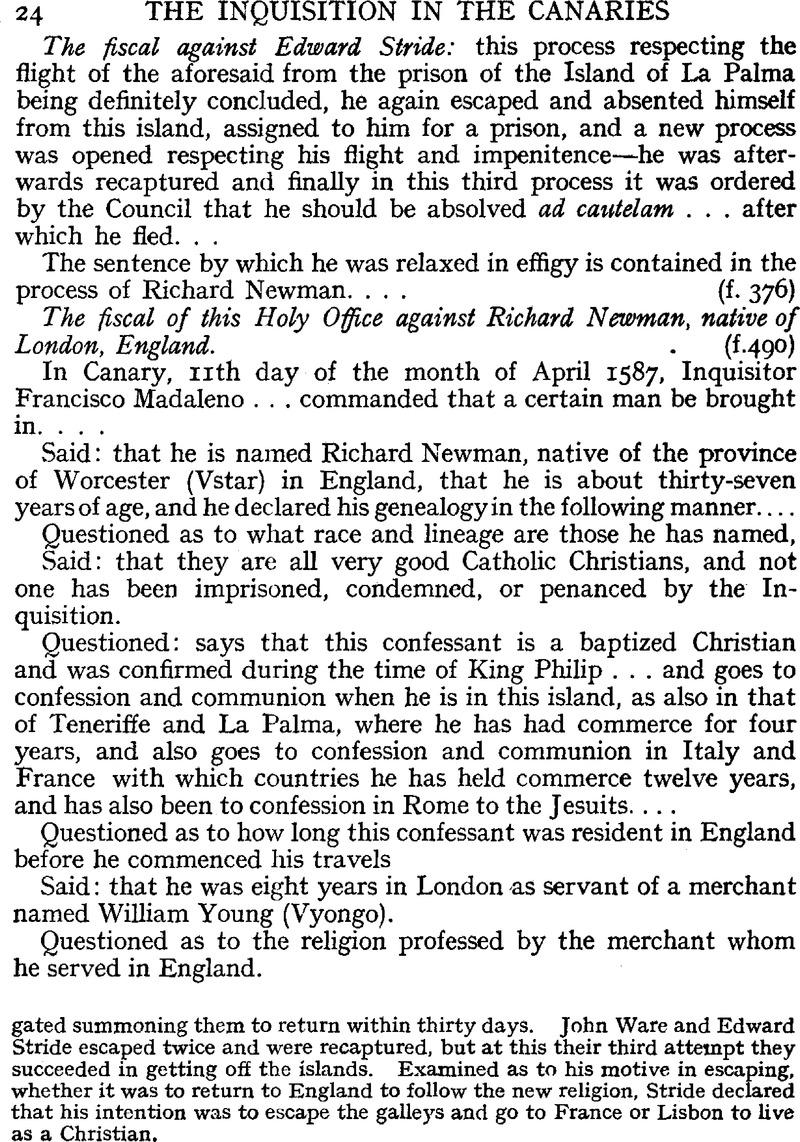

page 25 note 1 Probably John Young, who on Queen Mary's accession was appoìnted Master of Pembroke Hall, Cambridge, on Ridley's deprivation. He was also Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge from 1553–55, when he was made regius professor of divinity; he was not, however, a bishop. After Elizabeth's accession he was committed to prison in 1559 in the Counter, Wood Street, for refusing the oath. He was transferred to the Marshalsea before 1574, and temporarily released in the same year on the surety of Gregory Young (the MSS. has Guillermo Vyongo), grocer, of London, who it is presumed was his brother. (Dic. Nat. Biog.)

page 25 note 2 Corn and sugar were among the staple commodities in the trade between England and Portugal at this period (v. Chapman and Shillington, Commercial Relations of England and Portugal, p. 135, 147, etc.). Trade through Antwerp, though less in proportion to the whole trade than it had been at the beginning of the century, still bulked large. (Ibid., p. 141; v. also J. Wheeler's Treatise of Commerce.) Newman's voyage was typical of many which were made at that time.

page 25 note 3 Presumably hops. These are included in lists of exports from Flanders (e.g., in “ Certeyn thinges to be consydered of for the speciall welth of the Realme of England.” Dom. St. P. Eliz., vol. 185, No. 102).

page 26 note 1 “ Stuffs and kersies ” were among the goods most commonly sent from England to Spain. Wheat also is mentioned in the list of “ Commodities of ports where merchants trade as coming from the northerly parts of England.“ (Dom. St. P. Eliz., vol. 201, No. 14.) Oil, wine and fruit were the ordinary returns. The trade with Andalusia appears to have been the most common, and San Lucar was a favourite centre. In the reign of Henry VIII English merchants trading to Spain and Andalusia had received special privileges from Charles V (Harl. MSS. XXXVI, 6), and it was from the association of these merchants that the later “ Company of Merchants trading to Spain and Portugal ” was developed.

page 26 note 2 This passage is not very clear; but there was an embargo on all ships on the Spanish and Portuguese coasts in September, 1583 (Cat. Ven. St. P., p. 69, No. 167), and an embargo on French and English ships in June, 1585, which may be the two occasions alluded to.

page 27 note 1 Six ducats a month is so extraordinarily high a wage that some mistake in the report of the case seems probable. About this period gunners on English ships were receiving 10s. a month. (J. S. Corbett, State Papers relating to the Spanish War, 1585–7, Navy Records Soc. ed., vol. XI, pp. 258–62, 286, 336, etc.) It is true that gunners' wages were apparently rising; and the high reputation of English gunners may have induced a foreign captain like Francisco da Rocha Paris to offer high wages; but even so the disproportion is enormous.

page 27 note 2 Vianna was one of the towns in Portugal which had formerly been attached to the cause of Don Antonio, the claimant to the Portuguese throne. It seems possible from the grant of an English safe conduct that Francisco da Rocha Paris may have been one of Don Antonio's adherents, in which case he might hope to find greater trade facilities in Vianna than in Lisbon or Oporto, which were of far more commercial importance.

page 31 note 1 At this date three Jesuits had suffered death in England. Campion and Briant in 1581, and Cottam in 1582. Of these, Campion only had been in Rome as a professed Jesuit. On this question of attending the Protestant services neither Campion nor Parsons would have been likely to sanction any compromise. (Thomas Woodhouse, executed in 1573, and John Nelson, executed in 1578, though, strictly speaking, Jesuits, were only admitted into the Order after their imprisonment.)

page 33 note 1 The sentence concludes with the usual disabilities. It will be noted that though the accused were to be relaxed in effigy only, the delivering of them to the secular arm is not omitted, but the usual recommendation of mercy is, it being clearly stated that the authorities are to burn the statues. About this time Domingo de Sea, a Portuguese master of a caravel, was penanced and sentenced to pay a fine for allowing English sailors on board; he declared, however, that they embarked without his consent, and that, finding that they had no licence from the Holy Office, he had wished to land them. (Millares' Book, v, p. 100.)

page 33 note 2 Tenth public auto-de-fé. Besides the effigies of the four Englishmen, nineteen effigies of Moors who had fled to Barbary were also burnt; and seventeen persons were reconciled and penanced for various offences, amongst others two for bigamy. (Millares' Book, v, p. 109.)