No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 December 2009

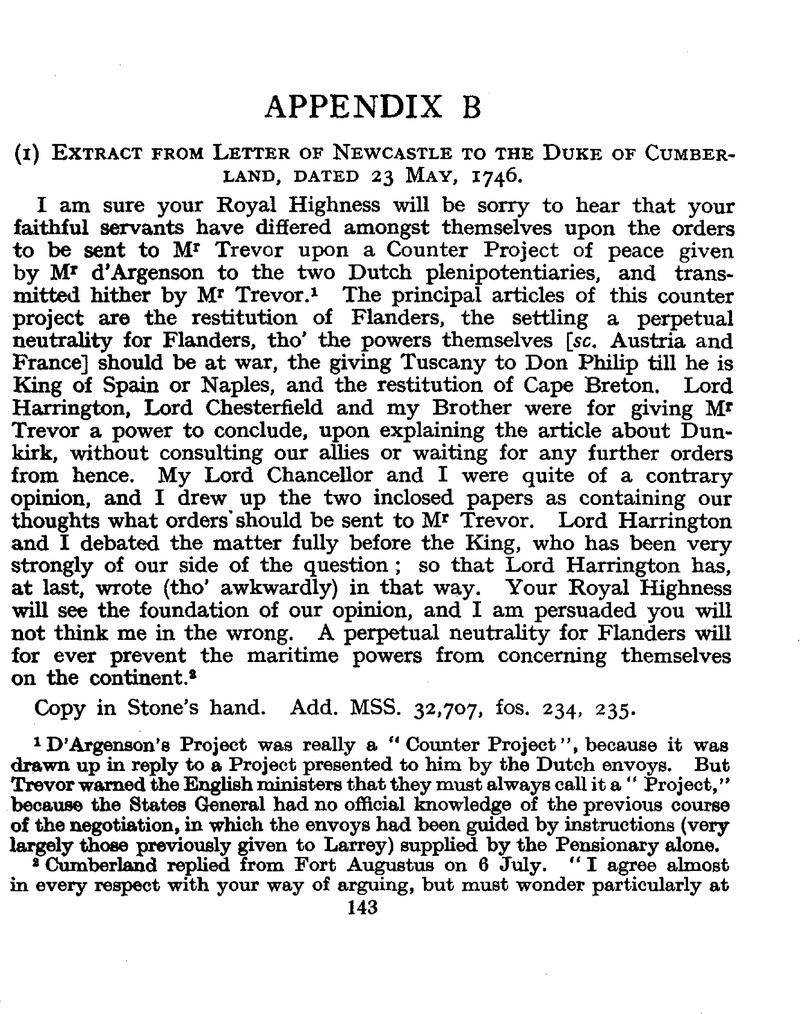

page 143 note 1 D'Argenson's Project was really a “Counter Project”, because it was drawn up in reply to a Project presented to him by the Dutch envoys. But Trevor warned the English ministers that they must always call it a “Proj ect,” because the States General had no official knowledge of the previous course of the negotiation, in which the envoys had been guided by instructions (very largely those previously given to Larrey) supplied by the Pensionary alone.

page 143 note 2 Cumberland replied from Fort Augustus on 6 July. “I agree almost in every respect with your way of arguing, but must wonder particularly at Lord Chesterfield, who I imagine would see the dangerous consequences of an eternal neutrality for Flanders” (Add. MSS. 32,707, fo. 288).

page 144 note 1 Nothing can be more characteristic of Newcastle than this assumption that Henry Pelham must have betrayed ministerial secrets to a visitor who had no official right to know them. Poyntz, in his reply, declared that he had not had any such information at Esher. The only possible defence of Newcastle, and it is quite inadequate, is that he may have had some idea of employing Poyntz in the negotiation with France. He did subsequently offer to send him to Breda, but Poyntz refused. Another reason for confiding in Poyntz was that he had been “governor” to Cumberland.

page 145 note 1 The above letters illustrate how completely important foreign affairs were reserved to the inner Cabinet. The other Cabinet ministers were not consulted. They also show that the King still possessed a dominant voice in the settlement of foreign policy. In this case he decided against the majority of his confidential advisers.