No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

Letters from King Charles I. to Queen Henrietta Maria. III

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 February 2010

Abstract

- Type

- Charles I. in 1646

- Information

- Camden Old Series , Volume 63: Charles I. in 1646. Letters of King Charles the First to Queen Henrietta Maria , April 1856 , pp. 6 - 9

- Copyright

- Copyright © Royal Historical Society 1856

References

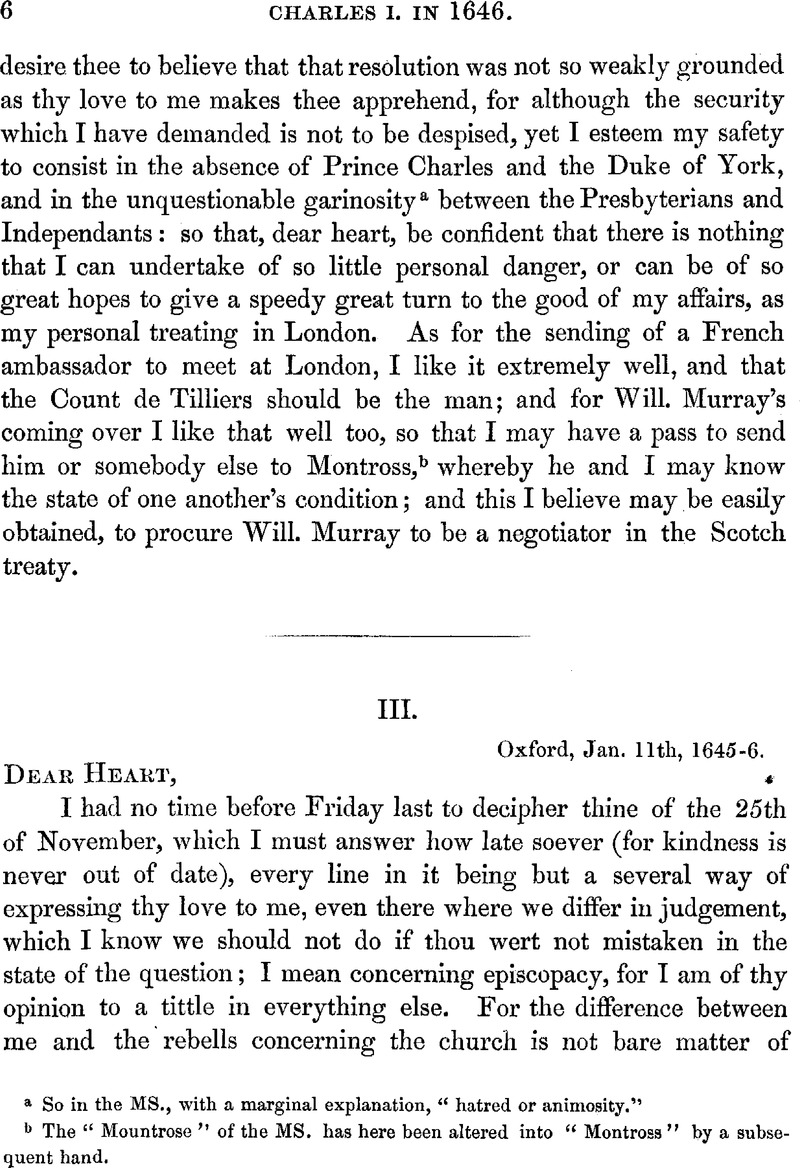

page 6 note a So in the MS., with a marginal explanation, “hatred or animosity.”

page 6 note b The “Mountrose” of the MS. has here been altered into “Montross” by a subsequent hand.

page 7 note a Marginal note in the MS. “base or low.”

page 7 note b This allusion explains a transaction which is merely glanced at by Clarendon (Rebell. book ix.), and has not been thoroughly understood by other writers. Clarendon says that “the gentlemen of the western counties,” no doubt alarmed at the state of public affairs, held various meetings and consultations whilst the prince was at Exeter, which terminated in a resolution to petition the prince “to interpose between the king and the parliament, and to send a message to the latter with overtures of peace.” The prince's council took this proceeding in bad part, and determined “that all endevours were to be used to divert and prevent any petition of such a nature from being presented to his highness,” which, Clarendon adds, “with great difficulty was at last prevented.” The noble historian gives no hint at the nature of the “difficulty ” alluded to, nor does he mention that prince Charles at this time sent a letter to sir Thomas Fairfax, who was in command of the army which was gradually hemming the prince in. In the letter to Fairfax it was professed that there was nothing which the prince more earnestly prayed for to Almighty God than the restoration of a happy peace, and he therefore requested Fairfax to send him, or to apply to the parliament for, a safe conduct for lord Hopton and lord Colepepper to go to the king with “some such overtures” as he hoped might conduce to peace. Fairfax remitted the prince's letter to the authorities at Westminster, with a report of his own, in which he stated that he thought it his duty not to hinder the hopeful blossom of the young peace-maker, which might “prove a flower in his title more glorious and sweet to us than the rest of his ancestors.” (Lords’ Journals, vii. p. 600.) The lords received the proposal favourably, but the commons, probably better informed, allowed it to die away. In Paris the transaction was turned in some way to the disadvantage of lord Colepepper. The king's allusion shews that the dissatisfaction of the gentlemen of the west amounted to a threatened mutiny, or desertion of the king, and that the letter to Fairfax was a mere piece of simulation had recourse to for the sake of influencing public opinion and quieting the mutineers. The “barbarous refusal” which the king seems to have esteemed a fortunate result of this little manœuvre, amounted to this. Application was made to Fairfax for an answer to the letter of his royal highness. Fairfax replied, on the 8th November, that he had not received any directions upon the subject from the parliament; “perhaps,” he remarked, “finding what counsels still prevail about his majesty, they may justly apprehend any such address to him would be fruitless if not hurtful to the end you propose [by] it, and yet, being loth to answer any desire from your highness with a public denial, may choose to suspend rather than give their resolution.” He added, that a better way to peace was by the prince's disbanding his troops and going himself to the parliament, where “he need not doubt of safety and honorable reception.” (Clarendon's State Papers, ii. 194.) Lord Capel replied, on behalf of the prince, that his royal highness did not believe his overture would have brought him an invitation to quit his piety and loyalty to his royal father; that, if his former propositions were consented to, he hoped Grod would bless his sincere intentions ; if rejected, he should give the world no cause to believe that he would forfeit his honour and integrity. (Fairfax Correspondence; Civil War, i. 259.)