No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

The Lauderdale Papers

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 December 2009

Abstract

- Type

- The Lauderdale Papers

- Information

- Camden New Series , Volume 36: The Laurderdale Papers. Volume II. - 1667–1678 , January 1884 , pp. 1 - 247

- Copyright

- Copyright © Royal Historical Society 1884

References

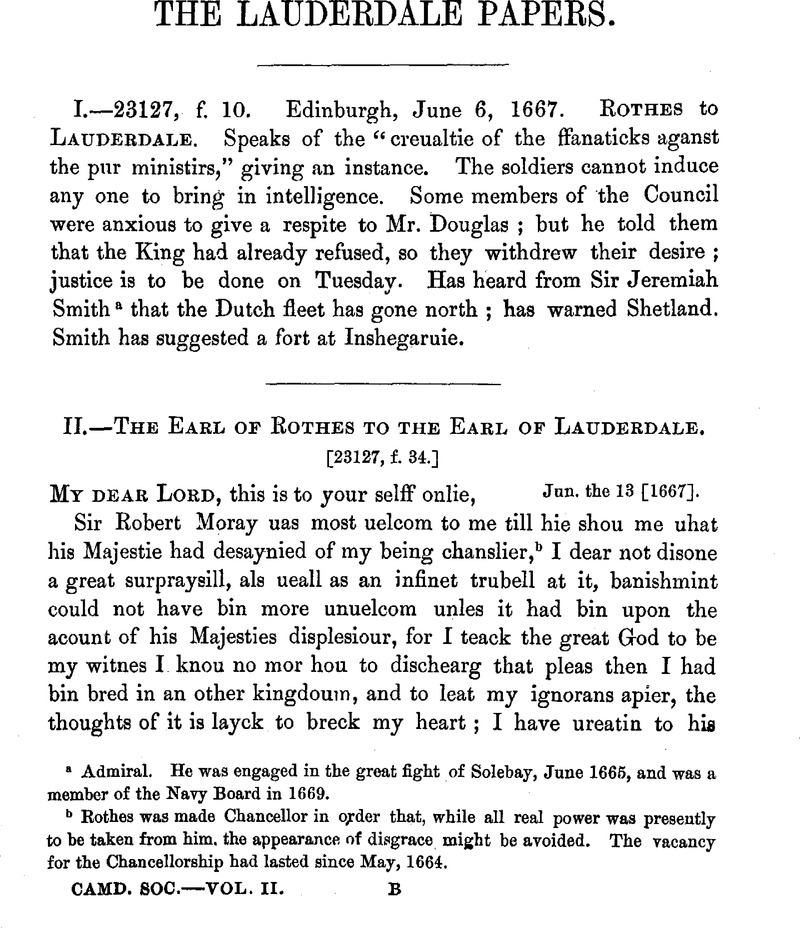

page 1 note a Admiral. He was engaged in the great fight of Solebay, June 1665, and was a member of the Navy Board in 1669.

page 1 note b Rothes was made Chancellor in order that, while all real power was presently to be taken from him. the appearance of disgrace might be avoided. The vacancy for the Chancellorship had lasted since May, 1664.

page 2 note a Who had sailed up the Thames.

page 2 note b This letter is an admirable example of Moray's easy narration.

page 2 note c The Treasury was now put into commission.

page 3 note a As with the Church Bill in 1669. Cf. p. 14. It will be seen that more than once Charles carried out in Scotland the policy that he wished England to imitate.

page 6 note a See Douglas's letters to Lauderdale, Camden Miscellany for 1883.

page 6 note b Privateers.

page 6 note c Drummond.

page 7 note a The Chancellorship.

page 7 note b This sentence is very difficult to construe. I think there should be a stop at “befor,” but cannot decide.

page 8 note a In 1663.

page 8 note b Robert Moray.

page 8 note c Wishart.

page 9 note a Duke of Hamilton.

page 9 note b Lord Commissioners.

page 9 note c Archbishop of Glasgow.

page 9 note d See p. 12, line 11. Apparently Hamilton is referred to.

page 9 note e I cannot tell who is meant.

page 9 note f Of Glasgow.

page 11 note a Pseudonym for Tweeddale, usually written shortly S.S.

page 12 note a Whose billet Primrose snipped.—Mackenzie, Memoirs, p. 75.

page 12 note b Bellenden was noted for Ms violent temper at the Council and Treasury.

page 12 note c See 23127, f. 69, p. 9.

page 12 note d e. g., Hamilton, see p. 39.

page 12 note e e. g., Dalyell.

page 12 note f The “Gormandizers,” Rothes and Hamilton.

page 13 note a See the colour put upon this hy Moray in 23127, f. 38.

page 13 note b Of. his letters in the Appendix.

page 14 note a Cf. p. 3.

page 15 note a With his usual cunning Sharp sees that it will be best for him to abjure Rothes and all his works. It had been through him that the money intended for the relief of the ruined nobility had been applied to raising the standing forces. Compare the letters in the Appendix.

page 15 note b Viz., that writing follows in sympathetic ink.

page 17 note a Wishart.

page 17 note b Moray afterwards says of Lauderdale, that he “knew how to make use of a knave as well as another.” See page 31, line 6.

page 17 note c Cochrane had been in the confidence of the archbishops and appears to have been gained by Lauderdale now.—Cf. Appendix.

page 19 note a For other cases see Archbishop Burnet's letter of Nov. 6,1667, in the Appendix.

page 19 note b See 23127, f. 88.

page 19 note c Dalyell.

page 19 note d Drummond.

page 22 note a The Chancellorship.

page 26 note a In Kirkcudbright.

page 26 note b Of Borge.

page 26 note c Of Balmaghie. They “ ruffillit” his house.

page 27 note a Governor of the Barbados.

page 28 note a That he was to be deprived of his see. See page 17.

page 30 note a Dumfries asserted the opposite in good round terms.

page 31 note a In an MS. letter of Moray to Kincardine, not included in the Lauderdale Papers, he gives a recipe for making this “vitriol.”

page 31 note b James Sharp. See page 28.

page 32 note a Sir Hugh Campbell of Cesnock, James Dunlop, and James Holburn of Menstryv were imprisoned in the Castle of Edinburgh in 1665.—See Wodrow, vol. ii. p. 99.

page 33 note a The taking of the Commissionership from Rothes.

page 33 note b Tweeddale elsewhere declares that Moray would make a “ non-such chancellour.”

page 34 note a Probably of resigning.

page 34 note b Archbishop of Glasgow.

page 36 note a Genesis xxxiv. 25.

page 36 note b Rothes, at least, was a notoriously immoral man. As to Hamilton, see later in this letter where Moray lays his corruption to Rothes' evil influence and his habits of drinking.

page 36 note c i.e., sympathetic ink. Cf. “stargazing,” in other letters.

page 37 note a I imagine this to refer to the Duchess of Hamilton and her sister, Lady Susan. In other passages I think Lady Margaret Kennedy is meant, from comparison with her letters as published by the Bannatyne Club; but I am not clear on the point.

page 38 note a For these views well expressed, see Kincardine's letter to Sharp, vol. i. of the Lauderdale Papers, pp. 229, 230.

page 39 note a Rothes.

page 40 note a This “our wife” is clearly not the same as the “our wife” in the following sentence. Comparing this with 23128, f. 6, it seems that the first “our wife” is Lady Susan Hamilton; and the second the Duchess. I cannot make out what the matter is which is referred to.

page 40 note b See 23127, f. 166.

page 44 note a The fall of Clarendon naturally strengthened the hands of those who were trying a toleration policy.

page 44 note b A reconciliation took place now between Lauderdale and Middleton. See Mackenzie, Memoirs, p. 49.

page 48 note a Burnet speaks of his “soft and insinuating address,” section 102.

page 49 note a See page 52.

page 50 note a Cf. the proverb “Souters (cobblers) should not be sailors.”

page 50 note b I cannot tell who is meant.

page 50 note c The “Gudeman of Ballangeich” was the name given to James V.; presumably here it means Charles II.

page 50 note d Dirty and uninteresting.

page 51 note a Meaning his brother, James Sharp.

page 51 note b The placing the Treasury in commission.

page 52 note a Wodrow, vol. ii. p. 90.

page 54 note a Robert Moray says in another letter of him: “W. Dr. did lyke a privy councellor, signed, though he voted against every particular.”

page 54 note b i.e. the writer, Tweeddale.

page 55 note a See p. 59.

page 55 note b The writer.

page 56 note a See p. 52. i.

page 57 note a Annandale and Queensberry.

page 58 note a Robert Moray himself. See p. 63.

page 59 note a This letter was the subject of a characteristic piece of duplicity of James Sharp. See Appendix for the letters of Sharp and Alexander Burnett, from the Sheldon MSS., bearing upon the matter. See also Scottish Review, July, 1884.

page 62 note a Hooding-sheaves are the sheaves which are placed so as to shelter the shocks from the rain.

page 63 note a See Charles Maitland's account, vol. i. p. 248.

page 63 note b See p. 58.

page 64 note a This should be compared with Kincardine's language, vol. i. pp. 229, 230.

page 66 note a Written in sympathetic ink.

page 67 note a Samples.

page 67 note b This advice was acted upon. See p. 71.

page 69 note a This letter is of especial interest, as explaining Lauderdale's conduct since 1660, and his successful management of Charles.

page 70 note a E.g., re-establishment of Episcopacy, the Church Commission, the policy of persecution, the application of fine money to maintenance of troops.

page 70 note b See ante, 23128, f. 32.

page 71 note a James Sharp.

page 72 note a Rothes's mistress was nearly related to the Marquis of Huntly.

page 76 note a Alexander Burnet, Archbishop of Glasgow.

page 76 note b Archbishop Sheldon. See Appendix for the curious history of this letter.

page 76 note c The writer himself. In his correspondence he frequently uses the mason's mark, especially when he wishes it understood that writing in sympathetic ink is to be expected.

page 77 note a Sir James Turner.

page 77 note b Kellie.

page 78 note a Now that he had been rendered powerless.

page 80 note a He returned in the middle of January following.

page 81 note a See ante.

page 83 note a Longifacies.

page 84 note a See 23128, f. 273.

page 85 note a Earl of Cassilis.

page 85 note b Lady Margaret Kennedy. This settles the question as to who one of “our wives” was. Other passages prove the second to have been the Duchess of Hamilton.

page 85 note c He married Lady Susan Hamilton in 1668.

page 85 note d Charles II.

page 88 note a Compiled by Mr. (afterwards Sir) James Stuart, of Goodtrees, and Mr. James Stirling, minister at Paisley.—See Wodrow, vol. ii. p. 100.

page 89 note a See ante.

page 89 note b Naphtali.

page 89 note c Sheldon.

page 90 note a See ante, 23128, f. 167.

page 91 note a Dear John Red.

page 91 note b See 23128, f. 213.

page 92 note a The King.

page 92 note b From the context this can scarcely mean John Red (Lauderdale); I fancy it means James Duke of York.

page 92 note c “To be in the dorts” is to be in the “sulks.” “Dorty,” as an adjective, may be either sulky, apt to take offence, or saucy, as applied to a girl. Moray says that Rothes will cloak any outward appearance of offence, however he may be used, unless he fairly “leap the (Dortor) Dyke,” i.e. let his ill-humour get over all restraint.

page 93 note a See ante, 23128, f. 167.

page 95 note a Daughter of George, 2nd Earl of Dalhousie, afterwards wife of George, 11th Baron Ross.

page 95 note b This is but one out of many such notices of the extreme poverty of the country.

page 99 note a Dumfries, it will be remembered, had been a prominent adherent of Middleton in the Billeting affair, had been employed by Sharp in his endeavour to form an alliance between Rothes and Middleton against Lauderdale, and had broken with Sharp over that matter.

page 99 note b Sic.

page 104 note a William Ferguson, of Lanark; was at Pentland, and was now banished to Virginia.

page 104 note a Rae.

page 105 note a The parentage of this plan has been disputed. As will be seen later Sharp is allowed to have the credit for politic reasons. It is the chief subject of the letters immediately following.

page 105 note b Grandson of Landerdale and Tweeddale. See footnote, p. 118.

page 106 note a Through Sharp's instrumentality. It appears, however, from 23129, f. 197, that Lauderdale and the Duke were not yet on good terms.

page 107 note a See Wodrow, vol. ii. p. 111.

page 109 note a Provost of Edinburgh.

page 116 note a Wodrow (vol. ii. p. 104) mentions a report that Ballantyne afterwards undertook a design, in London, upon Lauderdale's life. See his letter, p. 127.

page 118 note a Tweeddale's son, Lord Yester, married Lauderdale's only child, Mary.

page 120 note a Sir Robert Moray was Charles's chief companion in the laboratory; many of his despatches of 1663 were written from there.

page 121 note a In the first part of this letter Tweeddale urges Robert Moray's return as absolutely necessary.

page 125 note a This is asserted also by Tweeddale in a letter of Feb. 23, 1669, and still more emphatically on March 13. He says, “I know not if I told you that I had intelligence from the west that the starting up to preach and conventicle was upon information given by some ringleader to all the party that it was now fitt to try if the State would suffer that liberty was given in England, and that therefore some fell a preaching who never had done it before.”

page 126 note a This is the tone consistently used by Kincardine, who was a man of the highest capacity, as well as of exceptional political integrity.

page 127 note a a See footnote, p. 166. For his death, see Wodrow, vol. ii. p. 104.

page 131 note a Athole.

page 132 note a The coming Dukedom ? Lauderdale received it in 1672.

page 136 note a There are many things in “Old Mortality,” besides this original of Cuddie Headrigg, which make it almost certain that Scott had seen many of these letters.

page 137 note a This and similar passages should be borne in mind in the consideration of events like the Massacre of Glencoe. See Macaulay in loc.

page 137 note b For this paper, put forth by the Synod of Glasgow, presided over by Alexander Burnet, see Wodrow, vol. ii. p. 143, and Appendix to this volume. Lauderdale's reflection upon it (p. 141) is, “They will be Remonstrators by what name or title soever they are distinguished.”

page 139 note a This, I think, refers especially to the formation of the new militia, to which Charles was undoubtedly looking, in a somewhat indefinite way, as possible support to him against his English subjects. See the following letter. The more entire subjection of the Church is possibly also included in the “greate business.”

page 140 note a The blew bonnet was the headdress of the common Scotch soldiers of the Covenanting time, such e.g. as crossed the border in 1640. Buccleuch's guards were probably mounted with steel headpieces.

page 141 note a This formed the main ground of the threatened impeachment of Lauderdale. See Parl. History, vol. iv. See Lauderdale's letter for Nov. 16.

page 141 note b To conduct negotiations for the proposed union.

page 143 note a In a great passion, according to Mackenzie.

page 144 note a Hamilton. The Hamilton family pretended to be next to the crown of Scotland, if the succession of King James should fail.

page 144 note b Mackenzie.

page 144 note c See Lauderdale's letter for Nov. 16.

page 145 note a Robert Moray was a skilled chemist. In his correspondence with Kincardin during 1658–60 he describes how he is relieving the weariness of exile by making chemical experiments on a large scale.

page 145 note b Alexander Burnet. Longifacies, or Long Nez, as Bellenden called him.

page 146 note a For the pomp attending Lauderdale's journey see Mackenzie, Memoirs, p. 161.

page 146 note b See Wodrow.

page 146 note c I am quite unable to obtain any explanation of thia allusion.

page 147 note a A bridegroom who complains that his wife is too beautiful is taken as typifying the extremity of discontent.

page 150 note a Compare this with Lauderdale's letter of Nov. 9. In a letter of James to Lauderdale for Oct. 28, 1670 (in the possession of John Webster, Esq. M.P.), he too expresses an evidently genuine desire that the affair of the Union should go on well.

page 152 note a The action of Sharp is very amusing. It must be remembered that he had only lately, by abject submission, become reconciled to Lauderdale.

page 153 note a William Sharp.

page 154 note a See Moray's letter of Oct. 28.

page 154 note b See Mackenzie's Memoirs, p. 137 and following.

page 154 note c See following letter.

page 155 note a It is not easy, from this and following letters, to understand whether Lauderdale wished for Union or not. There will be noticed, however, several passages which, read in connection with “Mackenzie Memoirs,” p. 140, appear to support the view that the idea was distasteful to him, possibly from the idea that he would greatly lose power thereby. Burnet says that the idea was Tweeddale's, and that Lauderdale strongly urged its consideration, since it rendered a Parliament necessary, at which he would be Commissioner; but he intimates that it was never intended to be carried out, except by the King. Commissioners were named in the summer of 1670, but the thing fell through.

page 155 note b The next letter shows that Lauderdale had his way.

page 159 note a Upon receiving this account Lauderdale wrote as follows on the 18th November: “Alas, shall I never be trusted! But I will complain no more. Nobis obsequiis gloria relicta est. Fall back, fall edg, sure I shall obey, and either here or there I am confident the Union is choaked.”

page 160 note a Shaftesbury.

page 160 note b Bridgman.

page 160 note c Arlington & Trevor.

page 162 note a A passage is here crossed out.

page 163 note a This letter, apart from its actual contents, is of great interest. Bnrnet (sect. 286) says that, after Robert Moray's death, to whom the King had given it, it fell into Hamilton's hands, and that he himself saw it. He adds that it was intended to found an impeachment upon it.

page 166 note a Sheldon is usually written of under this name. Alexander Burnet was on terms of close confidence with him. See Appendix.

page 166 note b Cf. Lauderdale's caution to Moray on this subject in his letter for Nov. 9.

page 166 note a Carteret.

page 166 note a See Appendix.

page 169 note a Leighton.

page 169 note a Carteret.

page 172 note a Sharpe's action is thoroughly characteristic.

page 172 note b This hectoring tone now becomes usual with Lauderdale.

page 173 note a Mackenzie, Memoirs, p. 167. He asserts that it was passed in favour of Kincardine.

page 173 note b Mackenzie, p. 171.

page 174 note a See letters for Nov. 9 and 30.

page 175 note a See Appendix.

page 176 note a For the annexation, see Mackenzie, p. 175. It was a high-handed act against Morton, a political opponent, on account of the old grudge against Middleton, whose son-in-law he was.

page 178 note a See the two following letters. In England Quakers and Jesuits were regarded with equal suspicion. William Penn was indeed publicly accused by Tillotson with being a Jesuit. The fact, too, that Jesuits were found (or said to be found) in disguise as Quakers strengthened the idea [Broadmead Records]. It is unnecessary to add that the Quakers could look for no sympathy from Presbyterians.

page 179 note a I do not find these cases, or indeed this matter of Quakers, mentioned in Wodrow.

page 181 note a The entire novelty of Quaker doctrines seems to have puzzled even so clearheaded a man as Kincardine.

page 181 note b Leighton was now induced to succeed Burnet, in order that the policy of conciliation might have the best chance of success.

page 182 note a I cannot determine the meaning of this word; it is possibly connected with “reuery,” noise or disorder.

page 183 note a Apparently that described by Wodrow, vol. ii. p. 156.

page 184 note a Conciliation is now given up; henceforward Lauderdale's conduct, under the influence of Lady Dysart, is vulgar and brutal. See Wodrow, vol. ii. pp. 166 and following. Burnet, 292.

page 188 note a Hamilton. Mackenzie, p. 191.

page 188 note b Fining and close imprisonment, or banishing, by sending them to his Majesty's plantations in the Indies or elsewhere, as his Majesty's Council shall think fit. Aet anent deponing. Special instructions are given for the rigorous enforcement of this law.

page 192 note a Of Hamilton.

page 193 note a Inclosed in Tweeddale's letter of Aug. 3, 1669. It varies in some respects, especially in the last paragraph, from Wodrow's version.

page 200 note a It passed on the 13th. Lauderdale says about it: “I can, I dare say, [remove] any scruple against every title in it; the execution is left sumarie without any process, and every bodie concludes it will doe the worke. I heard but one ‘No’ to it, and that was the E. of Cassillis, according to the laudable custome of his fathers.”

page 200 note b “All that a law can doe, and past unanimously,” Lauderdale reports on 13th.

page 201 note a Daughter of the late Duke of Hamilton. For the abominable story regarding her husband, see Burnet, vol. i. pp. 227, 228.

page 202 note a He was at present on an embassy to Paris, where he was being completely duped on the subject of the Dorn treaty, both by Charles and Louis.—See Dalrymple's Memoirs.

page 203 note a She had been sent to France for her health; though, it is elsewhere stated, this was merely an excuse on Landerdale's part to get rid of her. The handwriting of this letter ia very broken. Her father was Alexander, first Earl of Hume, and her mother a daughter of Edward Sntton, Baron Dudley.

page 204 note a This letter should be compared with the accounts in Burnet and Wodrow.

page 205 note a Burnet.

page 205 note b Hutcheson.

page 207 note a This testimony, coming from Tweeddale, is most valuable.

page 213 note a Jus populi vindicatum.

page 214 note a See these in Burnet and Wodrow.

page 215 note a William Lockhart, writing on Sept. 5, says, “Your Lops presence heare next spring will be indispensably necessary.”

page 216 note a See Burnet's proposals at this time. History, i. 299.

page 219 note a In 1665; see vol. i. p. 228.

page 219 note b The chief offices of State were now absolutely in Lauderdale's hands.

page 223 note a There are no letters from Lauderdale during this Session. He was on his return to England on Oct. 22.

page 225 note a In the previous December Leighton says they will come neither to Presbyteries nor Synods.

page 227 note a Bois-le-duc.

page 227 note b The King: this pseudonym occurs in the letters at the time of the Billeting plot.

page 227 note c Lauderdale. The use of cypher is significant of the relations of distrust and suspicion which now existed between Lauderdale, Tweeddale, Argyle, Hamilton, and Athol. Burnet, i. 547.

page 228 note a Lauderdale's second wife.

page 229 note a I cannot identify the writer.

page 229 note b See Reid, History of Presbyterianism in Ireland.

page 230 ntoe a See Carte's Ormond (Clarendon Press), vol. iv. p. 452.

page 231 note a Afterwards Secretary of State under James II.; was with him at Saint Germains; and was created Earl of Monmouth by the old Pretender on James II.'s death.

page 231 note b Elect of Dumblane.

page 231 note c The second Duchess, Elizabeth Tallmarsh, Countess of Dysart in her own right.

page 235 note a See the letter from the Privy Council concerning this in Appendix B, p. Ixxiv.

page 236 note a Charles Maitland of Haltoun, brother to Lauderdale.

page 236 note b There is no mention of this in Burnet.

page 237 note a He writes on the same day in almost identical words to James.

page 237 note b He appears to mean Holland.

page 241 note a This privilege had been given to the Earl of Kincardin.

page 242 note a Hamilton and the malcontents henceforward went by the name of the “Party.” Lauderdale usually speaks of them as the “Faction.” See Mackenzie, pp. 253 following.

page 242 note b See the interesting account of this in Mackenzie, p. 257.

page 243 note a Polwart's proposal, above.

page 244 note a The pre-emption of salt, brandy, and tobacco.

page 244 note b Burnet, i. 363. The whole account bears the strongest evidence to Burnet's accuracy.

page 245 note a The usual place of such meetings. It was where the Billeting plot was formed.

page 245 note b See footnote to vol. i. p. 134.

page 246 note a This desire to change the Constitution was really a revolt against the system of personal government, which was secure so long as the present constitution of the Articles were maintained. It is more than probable that it was at Shaftesbury's advice.