Like all recently established media, early television was particularly self-conscious, alert to the imperative to construct and propagate an image of itself suitable for the world in which it had just arrived. A crucial component of this discourse was newness. Television was the most appropriate medium for contemporary society precisely because so much else in this society was also new, and therefore only a new medium could meet its expectations fully. By virtue of this newness, then, television could not fail to have an enormous impact on the lives of all those who watched it – and even those who did not yet watch it, since its rhetoric was one of progressive expansion and increasing imbrication into the whole of society.

This is especially true of Italian television, which arrived relatively late on the scene in 1954, once the initial results of the massive effort to shape a new country after the devastation of World War II were already visible, and when the idea of modernity was characterising Italy’s self-image to a significant and increasing extent. From its inception, Italian television never failed to trumpet how its meeting with education, politics, entertainment, sport, advertising, theatre and music would dramatically alter their fate for the better, making them not only more widely available, but also better suited to a world in rapid and bewildering acceleration toward a bright future. This future would leave behind for good the trauma of the war – which in Italy had also been a civil war between 1943 and 1945 – and of the fascist dictatorship that had led to it. This kind of rhetoric was often explicitly inflected in didactic terms. Television would teach Italians not only how to become better citizens of the new republic, but also how better to enjoy the cultural and material riches that the modern world had to offer.

The case of opera constitutes an eloquent instantiation of this discourse. The first opera to be televised by the Italian public broadcaster RAI on 23 April 1954 – only a few months after the beginning of regular transmissions (3 January) – was Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia. An anonymous short text introducing the event to readers of Radiocorriere, RAI’s house weekly, makes for compelling reading:

The Barber of Seville, Rossini’s most popular work and the most precious gem of Italian opera buffa, will launch a series of opera teletransmissions, with which Italian television makes a major commitment, given the technical and artistic challenges involved. This opera … has been chosen as the inaugural work because, in addition to its popularity, it is one of the few that entails the values of ‘true life’, that is to say, those values which, independently of any strictly musical merit, offer television the possibility of vivifying, streamlining and re-evaluating the old static structure of opera, making it more natural, more fluid, more pleasant, in other words reconciling it with our times. This is the task of television with regard to opera. Tomorrow, through exchanges with other nations, it will still be Italy that will have its say on the validity of a genre that belongs to it by historical decree.Footnote 1

Besides the emphasis on the modernising effect that television would have on opera, what is significant about this text is that the only reason implied – rather than openly stated – for RAI’s ‘major commitment’ is a nationalist one. Opera belongs to Italy ‘by historical decree’, and therefore Italy must show other nations how the genre should be televised. No more needed to be said, since it was evidently considered obvious that opera, despite its ‘old static structure’, mattered a great deal to Italians, at least in RAI’s view. Indeed, RAI would keep its commitment, at least for a while, broadcasting an opera live from its Milan studios every five or six weeks over the following three years, as well as transmitting staged productions from theatres – initially of individual acts only, given the enormous technical challenges involved.Footnote 2

Television turned to operetta just a few months after taking on opera, but its arrival on the new medium was clearly a less straightforward matter, at least judging from the many more words of explanation offered by Radiocorriere. In the first article devoted to the issue, Angelo Frattini opted for a narrative of return:

On the 14th [of October 1954] the first encounter between television and operetta will take place … [This date] coincides with the return of a possibly minor artistic genre, which has nevertheless known moments of true glory when its adherents were called Offenbach, Audran, Suppé, Planquette, Hervé, Lecoq, Valente, Dall’Argine, Johann Strauss and Oskar [sic] Straus, and, more recently, our Mario Costa, Giuseppe Pietri and Virgilio Ranzato. Operetta was on its way to decline, though, … but not before scoring a few memorable successes: in addition to Franz Lehár’s numerous ones … there were others no less resonant: just to name one, Benatzky’s Al cavallino bianco. Footnote 3

After delving into the huge Italian success of Ralph Benatzky’s Im weissen Rössl following its Italian premiere in 1931, Frattini concluded:

Now the illustrious Cavallino is back among us: the young, listening to its inspired tunes, will undoubtedly understand the reasons for its success, which is reviving, and those who are no longer young, hearing and seeing it again, will think with a little nostalgia of when they first heard it twenty years ago.Footnote 4

Television, then, would rescue operetta from decline by broadcasting one of its more recent successes. Notably, television’s modernising mission was not emphasised here. Instead, the role of the shiny new medium was simply to offer operetta another chance to work its magic on viewers, as it had done with remarkable success in the recent past, one which older spectators could easily remember. Nostalgia, explicitly evoked, was thus a major component of RAI’s intervention. Im weissen Rössl was a particularly apt choice, given its early reception as a mixture of nostalgia for bygone times (for example with the appearance of Emperor Franz-Josef among the characters) and modernity (its score was widely perceived as mixing modern ‘jazz’ with the couleur locale of the Austrian Alps).Footnote 5

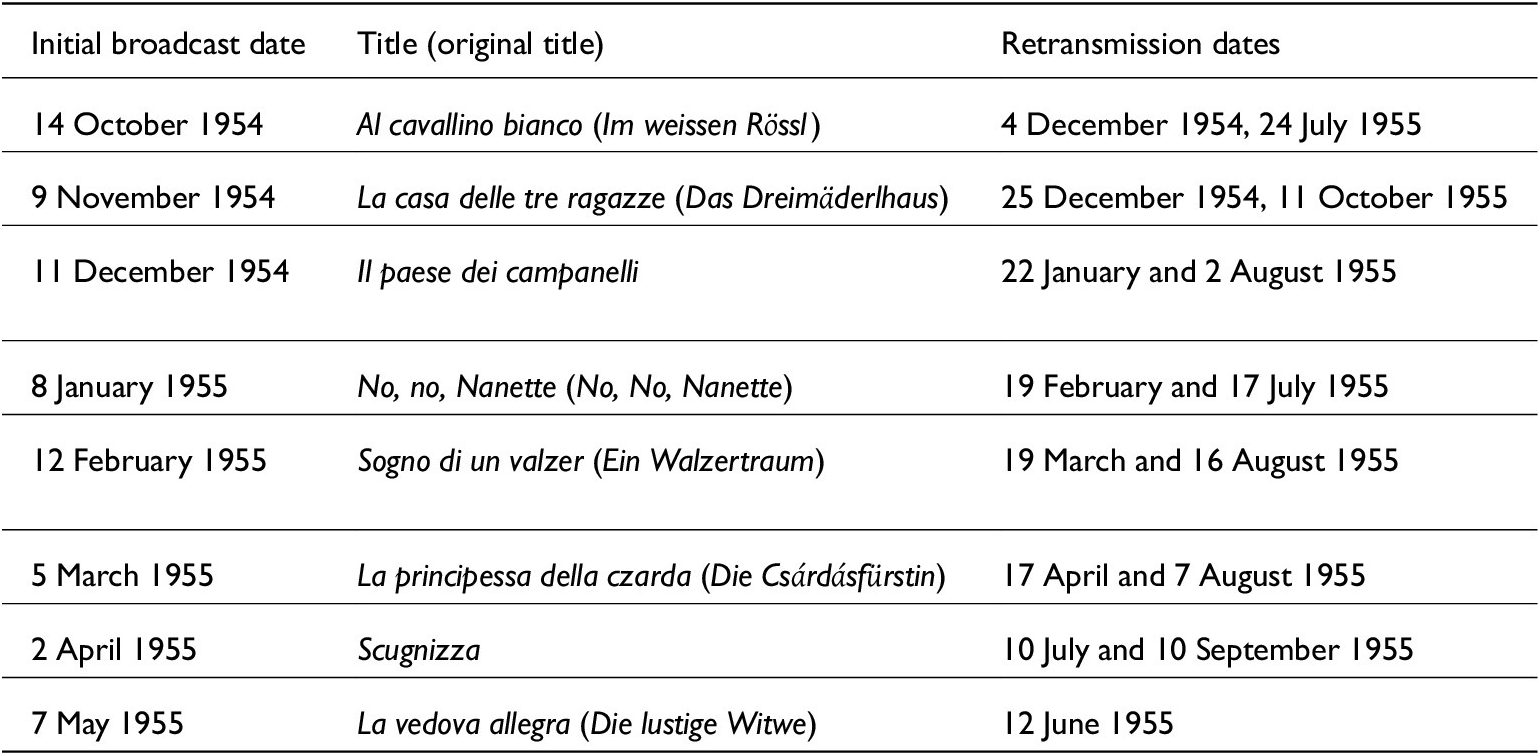

The broadcast of Al cavallino bianco was a success – or so RAI claimed in order to justify its decision to make a substantial commitment to operetta. Between November 1954 and May 1955 seven more works were televised. All these broadcasts were subsequently retransmitted twice, with one exception, as shown in Table 1 (which also includes the original title of non-Italian operettas, a matter which I will discuss later). In the space of almost exactly a year – between 14 October 1954 and 11 October 1955 – Italians could see operetta on television at a rate of about once every other week. After this early bout of interest, however, operetta disappeared from television for a few years, returning only in 1958–61 under different circumstances and in different guises.

Table 1. Operettas broadcast on RAI television, 1954–5

The initial encounter between operetta and Italian television has attracted no scholarly attention. This is no surprise, given that the small body of research investigating music on television, in Italy and elsewhere, has concentrated either on opera and ‘classical’ repertoires, or on popular genres.Footnote 6 And the study of mid-twentieth-century Italian music has focused almost exclusively on avant-garde composition or operatic performance, despite a few recent publications in Italian on popular music.Footnote 7 As a consequence, a significant and historiographically promising aspect of the encounter between mass media and music in Italy has been conspicuously neglected. My primary aim here is to begin to fill this gap, and in so doing also contribute to the current lively debate about the impact of technological innovations and new media on the production, consumption and conception of music in the twentieth century.

Some of the rich potential of this topic is already evident from the case of Al cavallino bianco. For one, mentioning nostalgia for ‘twenty years ago’ in 1954 cannot but strike us today as problematic, or at the very least worthy of attention, given that 1930s Italy was a fascist dictatorship, from which postwar society was ostensibly making every effort to distance itself. What is more, the 1930s is the decade when Italian operetta is usually presumed to have died out as a living genre, as I mention below. Therefore this discourse of nostalgia raises questions about both its object – what had television viewers actually heard ‘twenty years ago’? – and the ways in which nostalgia might have coloured perceptions of operetta in the 1930s from the vantage point of the 1950s. But there are other reasons that make the encounter between television and operetta in Italy worth investigating. Most compellingly, these broadcasts draw attention to the challenges of televising a mixed genre such as operetta in the technological context of the 1950s. Once again, the comparison with opera proves revelatory, as it does when attention turns to casting. Therefore, in what follows I address in turn the politics (broadly understood) of the 1954–5 operetta season, certain technological aspects of the production process, and the provenance and careers of performers – three aspects of potentially wide scholarly interest brought to the fore by an approach particularly alert to the methodological and historiographical implications of this kind of study. I then return to politics from a different – and perhaps surprising – angle that emerged after delving into the lives of a few performers and their activities during the final years of World War II and the immediate postwar era. Finally, I ponder what the case of the 1954–5 RAI operetta season may tell us about the functions and meanings of this genre in the context of Italian postwar culture. These different strands are complicated by a geographical perspective that pivots around Milan but also looks east and throws passing glances north of the Alps and to the south.

A ‘sleeping beauty’ from ‘happy times’

A consideration of the eight works included in the 1954–5 operetta season in terms of their place and time of origin, as well as the ways in which they were presented to the readers of Radiocorriere, raises a host of questions. Benatzky’s Im weissen Rössl was premiered in Berlin in 1930 and, as I mentioned above, reached Italy the following year as Al cavallino bianco. La casa delle tre ragazze was Das Dreimäderlhaus, a pastiche operetta with music by Franz Schubert rearranged by Heinrich Berté, performed first in Vienna in 1916 and in Italy four years later. Virgilio Ranzato’s Il paese dei campanelli premiered in Milan in 1923. Vincent Youmans’s ‘musical comedy’ No, No, Nanette opened both on New York’s Broadway and in London’s West End in 1925 after becoming a hit in Chicago during its pre-Broadway tour the previous year. It was brought to Italy three years later by the company of Paris’s Théâtre Mogador, which performed it (presumably in French) in several cities to widespread acclaim; an Italian version (retaining the English title) was staged in Genoa in 1931. Oscar Straus’s Ein Walzertraum (Vienna, 1907) first became Sogno di un valzer in Milan in 1908. Another Viennese work, Emmerich Kálmán’s 1915 Die Csárdásfürstin, reached Italy as La principessa della czarda in 1920. Mario Costa’s Scugnizza, based on a libretto by Carlo Lombardo (who also authored that for Il paese dei campanelli, besides writing some of the music for it), premiered in Turin in 1922; Franz Lehár’s 1905 Die lustige Witwe reached Milan as La vedova allegra two years later, in 1907.Footnote 8 The programme originally announced by RAI had included, instead of La principessa della czarda, Lehár’s 1909 Il conte di Lussemburgo (Der Graf von Luxembourg), which had arrived in Italy from Vienna the following year, and Giuseppe Pietri’s 1920 L’acqua cheta instead of Scugnizza. Footnote 9

RAI evidently privileged works from the twentieth century, bringing its operetta season to a close with the best known among them, Die lustige Witwe, which was also the oldest. Except for Ein Walzertraum, all the others had either reached Italy or been premiered there in the 1920s and 1930s. A documented history of operetta’s fortunes in twentieth-century Italy is yet to be written, but its gradual loss of standing beginning slowly in the 1920s and increasing in the 1930s seems incontrovertible. Therefore, RAI chose the works that had been most successful during the final decades of operetta’s popularity in Italy, which were precisely the 1920s and, to a lesser extent, the 1930s. In the 1950s, then, operetta was definitely perceived as having left its best years behind, but this supposedly glorious past was still sufficiently close to have been directly experienced by a significant portion of television viewers, to whose memory RAI appealed in order to promote its first operetta season.

The narrative of return first formulated for the broadcast of Al cavallino bianco in October 1954 would itself come back repeatedly during the following months, often inflected in more explicit and forceful ways. When Radiocorriere announced RAI’s commitment to operetta and the imminent broadcast of La casa delle tre ragazze in November, the same Angelo Frattini claimed in a long article that the success of the initial transmission had convinced RAI’s executives to offer viewers ‘not just an isolated sample of operetta – that very operetta that, like the protagonist of Perrault’s fairy tale, was a “sleeping beauty” well worth waking up with amorous élan – but nothing less than an operetta season, built around a varied and attractive programme’.Footnote 10 Frattini was evidently toeing RAI’s line rather than promoting a personal viewpoint. Besides working for various periodicals since the 1920s, between the early 1920s and the early 1950s he had also authored several successful riviste, theatrical entertainments that gathered together sung and danced musical numbers and comic sketches loosely related to a general theme, rather than contributing to an overarching storyline as in operetta.Footnote 11 The rise of the rivista is generally considered the main cause of the gradual decline of operetta in interwar Italy, and is indeed indicated as such in Frattini’s first article. He cannot therefore be suspected of particular sympathies for operetta: if anything, he was on the side of the genre that had put it to sleep.Footnote 12

The next piece on operetta in Radiocorriere, introducing readers to the transmission of Il paese dei campanelli, was written not by Frattini but by the writer and journalist Mario Sanvito. But the tone was similar, if more emphatic. Sanvito chose to interview the elderly Gianni Chighizola, who – the article explained – had been the first to conduct the work after Ranzato (its composer) in 1923. This distinction

is a reason for pride on the part of the maestro, and at the same time a source of nostalgia for a genre that no longer enjoys full houses and for which dozens of companies of both primary and secondary importance toured Italy, all disciplined and dignified and intent on respecting, as far as possible, the needs of a genre that had the right to be accepted within the boundaries of art.Footnote 13

Nostalgia for a time when operetta was considered art is couched in words that expressly evoke discipline, dignity and respect. Sanvito then informs his readers that the previous year Maestro Chighizola had again conducted Il paese dei campanelli ‘among houses hit by bombs, where the Teatro Verdi stood, another Milanese space whose memories are linked to operetta’s history’. The Maestro was overjoyed to hear that television would be broadcasting Il paese dei campanelli. It will be ‘a sort of family party’:

Will Bonbon [the soubrette] repeat the joke that, during operetta’s golden era, was considered extraordinarily bold, when she explained why she chose her name: ‘They call me Bonbon because when I see a man I melt like sugar…’? People found this funny back then. And they were happy times.Footnote 14

Sanvito’s narrative is not only overtly nostalgic, then, but emphasises order (discipline, dignity and respect) and innocence (happy times when an innocent innuendo was considered extraordinarily bold). What is more, the destruction brought about by the war is explicitly connected with the destruction of operetta, whose golden era evidently corresponds with the fascist ventennio.

The substantivised adjective ‘nostalgico’ entered the Italian language in the postwar years to indicate – according to the standard historical Italian dictionary – somebody ‘who longs for a political regime or the institutional and social structures of a very recent past; who advocates for their return and acts and plots with such an intent (with specific reference to the supporters of the restoration of fascism or of the monarchic regime)’.Footnote 15 I am certainly not claiming that expressing nostalgia for the golden era of operetta meant plotting for the restoration of fascism. In postwar Italy, though, any talk of nostalgia for the recent past could acquire implicit political meaning, especially if order and innocence were evoked – a process of signification akin to voicing longing for a time when trains ran on time, which in present-day Italy is generally understood to refer to fascism.

Although the rhetoric of order did not reappear in the many words that Radiocorriere devoted to televised operetta during the 1954–5 season, that of innocence certainly did – as did the discourse of nostalgia for the recent past and its welcome return, which television had made possible. The title of Frattini’s second, longer article of November 1954 set the tone: ‘The operetta season on TV: A world coming back’. But this prompts the question: Which world, actually? Which past was evoked when television’s capacity to bring it back was celebrated? As I hope emerges from my previous discussion, any attempt at a comprehensive answer – if such a thing were possible – would be anything but straightforward and would have to consider a wide range of factors, including political and ideological ones. I address some of them further below.

There is one factor, though, that turns out to be quite simple: nationality. Of the eight works televised, only two were Italian, Il paese dei campanelli and Scugnizza; with the exception of the American No, no, Nanette, all the others were of Viennese provenance.Footnote 16 Thus whatever past world was coming back, it was not in any meaningful way a nationalist one – although given that RAI chose the works that had been most successful in Italy most recently, it could be construed as national. A more or less overtly nationalist operetta season in 1954–5 would have been possible, given that the interwar decades had produced a number of lasting successes. Besides Costa’s Scugnizza and Ranzato’s Il paese dei campanelli, this list included Pietri’s Acqua cheta (initially scheduled instead of Costa’s work) and his earlier Addio, giovinezza! (from 1915 but very famous in the 1920s), Lombardo’s Madama di Tebe (1918) and Ranzato’s Cin-ci-là (1925), to mention only the best-known works. That the chosen season largely comprised foreign works therefore makes the nostalgia so often mentioned less political, given fascism’s strong nationalist bent. The ‘problem’ was that operetta in Italy during the fascist ventennio was not straightforwardly ‘fascist’, remaining instead a stubbornly transnational phenomenon – or, better, to use a word that had decidedly negative connotations in fascist Italy, ‘international’ – despite the regime’s half-hearted attempts to italianise some of its language (for example, by trying to substitute brillante for ‘soubrette’).Footnote 17

Consequently, unlike opera, operetta could not remotely be said to belong to Italy, by historical or any other decree, and television’s decision to take it up could not be justified on nationalist grounds. The real reason behind this decision seems clear: television had several hours a day to fill with programmes, and it turned voraciously to wherever there was potential fodder for broadcasting – in the first instance towards theatre in all its forms.Footnote 18 RAI’s rhetoric, however, was that of a rescue intervention, with television breathing new and modern life into a genre that was old, yes, but not hopelessly so, especially given the superpowers granted television by its modernity. A broad consideration of the institutional discourse of the initial encounter between Italian television and operetta, then, exposes a complex enmeshment of old and new, past and present, nostalgia and progress that is not only uncharacteristic of television’s usually more straightforwardly forward-oriented rhetoric – as the comparison with opera suggests – but also reveals operetta as precariously located on cultural, social and political fault lines in 1950s Italy. And this is not the only perspective from which operetta’s in-betweenness comes sharply into view.Footnote 19

‘The unity of voice and face’

In December 1956, after more than two and a half years of opera broadcasts from television studios and at the apex of RAI’s engagement with this kind of transmission, Radiocorriere published a photo-reportage entitled ‘How opera on television is made: The stages of a long musical journey’. It explained how the music was recorded in advance in Milan’s Teatro dell’Arte (close to the city’s RAI studios). Then, it continued, ‘after the recording, singers become actors’: in rehearsals they ‘“act” without singing, that is, they make sure that each word is tightly “synchronised” with the music’ – here the quotation marks suggest how new some words and concepts still were, including the notion of a split between acting and singing. Later, at the dress rehearsal, ‘singers sing under their breath [accennando, marking], following their own recorded voices that are played back [diffuse] in the studio’. This is because

live broadcasting of singing and music is not advisable on account of several factors: first, the orchestra would take up too much space in the studio; second, because of the built-up scenery, the singers would not always see the conductor; thirdly, the microphones cannot easily follow all the performers in their constant movements on the stage.

Finally, during the live broadcast of the action,

the ‘mixer’, following the director’s orders, selects for transmission this or that among the images that the various cameras send to the screens [in the control booth]. At the same time the recording of the singing and music is aired, which the performers also hear in the studio by other means, adapting their performance to it.Footnote 20

The ‘technical and artistic challenges involved’ in this kind of broadcast, then – mentioned in the anonymous text about the initial Barbiere di Siviglia of April 1954 with which I began – were clearly no exaggeration.

Such a claim was never made for spoken theatre, even if it constituted a much bigger commitment on the part of television in terms of the sheer number of broadcasts. But it was much easier to produce, as both audio and video elements were entirely live. In fact, when a play was transmitted twice, on Friday night and again on the following Sunday afternoon (as was often the case in these early years), it was performed and broadcast live on each occasion, because the technical challenges involved were evidently not so high as to justify the use of expensive film to archive the programme for retransmission. It was only with the advent of magnetic tape at RAI from 1959–60 that editing and archiving TV programmes became considerably easier and cheaper. Operetta thus poses an intriguing methodological and historiographical challenge, because the 1954–5 broadcasts were evidently considered worth keeping. Indeed, they were retransmitted twice during that season (except La vedova allegra, only once); as a result, they have survived and are available in the RAI archives.Footnote 21 My initial viewings suggested that, while the video was always live (for the initial broadcast), the audio alternated between live (for the spoken dialogues) and pre-recorded, with the actors lip-synching to their own singing voices for the musical numbers, following the same process used for opera. But further research challenged this conclusion.

Vito Molinari (b. 1929) is one of the most prominent directors in the history of Italian television. Aged only 24, he directed RAI’s very first official broadcast, the inaugural ceremony that opened regular transmissions at 11:30am on 3 January 1954. He went on to direct thousands of programmes until the 1970s, mostly entertainment shows of various genres, including operetta (but never opera). In 1954–5 he was associate director (collaboratore alla regia) of Al cavallino bianco and La casa delle tre ragazze, directed by Mario Landi, and primarily responsible for No, no, Nanette and La principessa della czarda. He would go on to direct fourteen more operetta programmes between 1958 and 1963, and three in 1974 – always as both stage and video director, as was common at the time. On the basis of his early RAI work in this genre, he was regularly invited to stage operettas by several Italian theatres between the 1950s and the early 1970s, and more sporadically until 1999.Footnote 22 Among his various books is La mia RAI, published in 2022, in which he states that early operettas were broadcast entirely live, singing as well as speaking. Referring to Al cavallino bianco, he recalls that the television studio ‘had to accommodate also the big orchestra conducted by Maestro Cesare Gallino, because actors [interpreti] sang in real time, live [in diretta, dal vivo]’. A few pages later, Molinari writes that No, no, Nanette was ‘exclusively in real time, sung live, with the orchestra in the studio, conducted by Cesare Gallino. This was my first important show [regia]: I remember being moved by the applause of the whole crew at the end of the broadcast.’Footnote 23 During an interview that he kindly granted me at his home in Chiavari, Liguria, on 1 April 2023, he repeated (when asked directly about his early television operettas) that these broadcasts were entirely live, with the orchestra placed at one end of the TV studio and assistant conductors standing behind cameras and relaying to singers the main conductor’s gestures in real time.

This production process matches that of operetta broadcasts by RAI following the introduction of magnetic tape (many also conducted by Gallino), which, however, were not transmitted live. Nonetheless, I remain doubtful that the 1954–5 operettas were produced in the way Molinari describes, on the basis of repeated viewings of the surviving broadcasts following our interview, including the four directed or co-directed by him. The synchronisation between singing and the movements made by the actors’ mouths, although in general remarkably good, is occasionally less than perfect. Moreover, the sound of spoken dialogue comes across as more ‘present’ than that of sung numbers, with voices seemingly resonating in a different acoustic space, while the often-vigorous dancing during the sung numbers produces no noise whatsoever. Finally, and to my mind most importantly, actors often turn away from the camera while singing, sometimes for several seconds, and therefore could not possibly see the assistant conductor; they also move about in ways that would seriously hinder singing of the quality and precision heard in the recordings, not to mention coordination between voices and orchestra.

I have no intention of dismissing or belittling the invaluable testimony of a protagonist of the historical events and objects that I study, whose exceptionally long life and great courtesy have made it possible for me to have a much more direct connection with these events and objects than historians are normally granted. It seems wise, then, to take a step back from trying to determine the exact production process of the 1954–5 broadcasts. A question worth asking remains, though: why is it seemingly so important for both Molinari and me to discuss the production techniques of these broadcasts, especially regarding the voices and their relationship with bodies? RAI must have also considered this issue relevant, if the editor of Radiocorriere decided to devote a substantial photo-reportage to the production process of studio broadcasts of opera, with an accompanying text that explained in detail how voices were recorded and what the singers did in order to create the impression of unity of voice and body, explicitly mentioning ‘synchronisation’, which had become old hat in cinema but was a new concept for television.

When addressing this issue, it is useful to differentiate between chronological frameworks and genres. Concern about the split between voice and body, although by no means unknown before the twentieth century, became pressing with the arrival of cinema, and returns to the centre of attention with each technological development in audiovisual media. Steven Connor has argued that ‘My voice, as the passage of articulate sound from me to the world … is something happening, with purpose, duration, and direction. If my voice is something that happens, then it is of considerable consequence to whom it happens, which is to say, who hears it.’Footnote 24 With the advent of audiovisual media, though, not only the who, but also the when and where of voice acquire crucial importance. If, in Connor’s words, ‘the voice always requires and requisitions space’, starting in the twentieth century the question of space became absolutely central, on account not only of audio-only media, but especially of audiovisual ones, where this space is represented.Footnote 25 As Rick Altman has famously declared, ‘fundamental to the cinema experience is a process – which we might call the sound hermeneutic – whereby the sound asks where? and the image responds here!’.Footnote 26 But what happens if the image’s answer is not quite as categorical? Questions such as these have been posed repeatedly by scholars of audiovisual media, from Altman to Michel Chion and many others.Footnote 27 And those concerned with the encounter between these media and forms of representation in which the voice plays an absolutely central role (such as opera) have discussed the issue at some length.Footnote 28 No surprise, then, that RAI did the same back in 1956 and Molinari and I (in this article) have also done much more recently, although our primary interest is operetta.

If we now shift our perspective from this very wide chronological framework to the much narrower one of the mid-1950s, and focus on a specific country (Italy), a specific medium (television) and specific genres (opera and operetta), a particularly complex situation emerges. After about fifteen rather experimental years following the arrival of sound film, the late 1940s and early-to-mid-1950s saw a sustained engagement with opera (but not operetta) on the part of Italian cinema, whose most interesting outcome was about twenty so-called cineopere, films of operas (inevitably in shortened versions) entirely or almost entirely sung that met with significant national success, and in which actors and singers might or might not be the same person, depending on whether singers’ bodies and acting abilities were deemed suitable for cinema. When they were different, as was often the case, especially for leading roles, the lip-synching often strikes us today as astonishingly inaccurate – which may have been of less concern to audiences used to actors being dubbed, either by themselves or others, as regularly happened in Italian cinema at the time, when speaking voices were rarely recorded ‘live’ on set.

As we have seen, operas broadcast from TV studios also systematically relied on lip-synching, although here bodies and voices always belonged to the same person, and therefore their ‘synchronisation’ was not only more accurate, but also easier to assume. Television is not cinema, though, and it emphatically was not back then, not simply on account of very different screen sizes, but especially since television was mostly entirely live – both sound and vision (except films, of course, but these were rarely broadcast in those years). Moreover, its discourse was one of ‘reality’, ‘truth’ and ‘intimacy’, its purported function being to show the world as it really was from up close – ‘a window onto the world’, as contemporary rhetoric had it. The fact that, for opera, sounds and images were not captured at the same time, and voices and bodies were therefore initially split before being sutured back together, was then much more marked than in cinema, and evidently needed explanation.

As for operetta, it is again Molinari who points us in a fruitful direction. Discussing his Principessa della czarda, first broadcast in March 1955, he recalls that

when it came to produce it, a problem arose: RAI’s casting office had contracted a soprano with a most beautiful voice [vocalità], but not exactly attractive (she was even cross-eyed!), and who could not dance. It was unthinkable that she could interpret Sylva Varescu, the star of Budapest’s Orpheum. There was a lot of negotiating: in the end I managed to go beyond the mandatory requirement [obbligo] of the unity of voice and face [unità voce-volto]. The end credits would declare that the voice was the soprano’s and that, in the broadcast [in video], an actress had mimed it for the singing. I had chosen the soubrette Elena Giusti, very beautiful and a good dancer. Moreover, the timbre of her voice was remarkably close to that of the soprano whom she had to mime for the singing. The result was perfect: nobody noticed the substitution.Footnote 29

This substitution was clearly a last-minute affair, since, to accompany its customary introduction to the broadcast, the Radiocorriere issue for that week published a photo of soprano Pina Malgarini, who ‘will perform the role of Silvia [sic], the operetta’s protagonist’, as the caption indicated (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A photograph of Pina Malgarini, who was initially supposed to sing and act the part of Sylva in La principessa della czarda, published in Radiocorriere (27 February–1 March 1955), 12.

The ‘unity of voice and face’, as Molinari calls it, was clearly a mandatory requirement on television, even if audiences were perfectly used to its absence in contemporary cinema. It seems highly significant, then, that this rule was breached for the first time for an operetta broadcast. The photo of Malgarini shows a medium shot of a young woman whom I think most people would have no hesitation in calling attractive – and who, at least in the photo, does not look cross-eyed. In any case, RAI knew perfectly well that, for these kinds of broadcasts, television – the medium that combined ‘reality’ with ‘intimacy’ – required performers that ‘looked the part’.Footnote 30 I would suggest, then, that the real stumbling block was not looks, not the ‘face’, but Malgarini’s apparent inability to dance, and therefore not so much the shape of her body as how it moved. This is what distinguishes operetta from opera in this respect and made operetta so much harder to broadcast back then. Referring to his experience with La casa delle tre ragazze in November 1954, Molinari writes that ‘I become ever more firmly convinced that operetta is the most difficult genre to produce, and also the most expensive, but also the most intriguing and fascinating.’Footnote 31 Thus the televisual imperative of the unity of voice and body was first challenged not by opera, not by the superior and quintessentially Italian genre whose production process was patiently and openly explained to its audience. Instead it was operetta, the humbler, ‘international’, and outdated genre whose mixture of acting and dancing and of speaking and singing demanded something that television evidently struggled to provide.

Televised operetta, then, warns us against setting up any easy dichotomy that, considering the Italian media landscape of the 1950s, we might be tempted to establish between body and voice, between musical and non-musical audiovisual genres, and between cinema and television. In ‘normal’, mostly spoken cinema the body led and the voice followed, while in cineopere the opposite was true, at least in the production process. In cineopere body and voice could belong to different performers, while in televised studio productions of opera the performer was always the same. In televised operetta, though, the demands placed by the genre on both voice and body – to be sure, almost exclusively female voices and female bodies – were so weighty that occasionally the perfect suture that the medium strived for had to be shown for what it was, an illusion. Yet as Malgarini’s substitution shows, the pursuit of this illusion could have a significant impact on individual performers; it is therefore to performers that I now turn.

Casting across media and genres

Where, then, did television seek performers that could meet not only its technological demands but also its theatrical, psychological and (perhaps) affective requirements? Reconstructing the careers of the actor–singers involved in the 1954–5 operetta season is far from easy, since most of them were not sufficiently prominent or famous to leave behind significant traces. Amongst the secondary literature and online archives, however, there is sufficient data for some intriguing initial considerations. It seems sensible to start from the two performers involved in the ‘misunderstanding’ surrounding La principessa della czarda.

Pina Malgarini had been cast in minor parts in a few films, including Luciano Emmer’s comedy Domenica d’agosto (1950) (where she was dubbed with somebody else’s voice) and Giuseppe Di Martino’s L’amore di Norma (1951), a so-called ‘parallel opera’ in which the lives of the protagonists – opera singers – closely resemble those of the characters they portray in an opera that they sing on stage (in this case obviously Bellini’s Norma). She had also acted (but not sung) the part of Matilde and sung (but not acted) that of Jemmy in Libera Elvezia, a dramatically shortened film version of Rossini’s Guillaume Tell; acted (but not sung) Norina in Largo ai giovani, an equally compressed production of Donizetti’s Don Pasquale; and sung (but not acted) Susanna in Un matrimonio difficile, a similar précis of Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro. All three films were shot on the stage of the Rome Opera, lasted a little over twenty minutes (including spoken narration to link the different musical excerpts) and were released in Italian cinemas in 1948, presumably as curtain-raisers to full-length features; they were broadcast in the USA the same year.Footnote 32 Malgarini’s main career was as an opera singer, though. She seems to have been active especially at Naples’s Teatro San Carlo and at the Rome Opera, taking on mainly lyric roles: Mimì in Puccini’s La bohème and Nedda in Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci at the former, for instance, and Butterfly (Madama Butterfly), Liù (Turandot) and Musetta (La bohème) for the latter.Footnote 33 Prior to her 1955 television appearance she had also recorded Micaela’s aria in Bizet’s Carmen, again with the Rome Opera.Footnote 34 After 1955 she continued to sing occasionally at the San Carlo, at the Rome Opera and in provincial theatres, but she was particularly active on RAI radio, where she had already appeared in 1954 and would continue until the early 1970s in several concerts and complete operas.Footnote 35

Like Malgarini, Elena Giusti had some film credits before 1955, mostly as the soubrette in comedies that were set in the world of the rivista, or that included extended scenes from theatrical riviste – Mario Mattoli’s I pompieri di Viggiù (1949), Carlo Alberto Chiesa’s I due sergenti (1951) and Camillo Mastrocinque’s Café chantant (1953) among others. This was because she was already famous in this kind of show, where she had appeared regularly since the early 1940s – in the early 1950s mostly partnered by Ugo Tognazzi, who would go on to become a major film and television star. Her rivista-related fame had already secured her a solo TV programme entitled Album personale (8 February 1954), directed by Molinari, in which she sang, danced and chatted, and a few other appearances in entertainment programmes. Her evident success in La principessa della czarda was probably the reason she was cast as Gaby in the following operetta broadcast by RAI, Scugnizza, in which she obviously sang as well as acted.Footnote 36

Although there is some overlap between the pre-1955 careers of Malgarini and Giusti, they were clearly different kinds of performers. Malgarini had mostly worked in opera to a relatively prominent level, which included a recording of Carmen (highlights) and the lead parts in front-ranking houses. As far as I have been able to establish, she had been active only since the late 1940s, and never in operetta before the Principessa della czarda affair. Giusti, on the contrary, had been a well-known rivista performer since the early 1940s – she was born in 1917 and may have been older than Malgarini (whose date of birth I have been unable to establish). She had not been previously involved in operetta either, but her rivista credentials made her a much more suitable operetta performer than Malgarini, given the contiguity between the two genres in terms of the demands they placed on their female protagonists. While Malgarini could sing but evidently not dance – which opera singer could or indeed can? – Giusti could dance and sing, and quite well too, at least judging from her performance as Gaby in the TV Scugnizza. The only occasion I have traced where she did not do both was in Molinari’s Principessa della czarda. In this respect Malgarini was less consistent, supplying either her voice or her body in the films in which she was involved.Footnote 37 This was less unusual than we might imagine, though, since there are several other instances of opera singers who sang and acted in one cineopera but lip-synched to somebody else’s voice in another. For example, Nelly Corradi and Gino Sinimberghi gave both voice and body to Adina and Nemorino in Mario Costa’s 1946 Elisir d’amore, but just body to Leonora and Alvaro in Carmine Gallone’s 1949 Forza del destino – the vocal parts, much too heavy for Corradi’s soprano leggero and Sinimberghi’s tenore di grazia, were sung by Caterina Mancini and Galliano Masini.

If we now place Malgarini and Giusti in the context of the other performers in the 1954–5 RAI operetta season, Giusti emerges as far more representative, mainly on account of her significant career in the theatre – most of these actor–singers had years of experience in operetta and rivista behind them. The theatrical roots of television are well known to historians, but they are perhaps nowhere deeper than in Italy, where, after being given the cold shoulder by the world of cinema, RAI had turned to theatre to help set up the new medium. Molinari’s career is indicative of this phenomenon, since he had come to the attention of Sergio Pugliese, RAI’s head of television, as a theatrical actor.Footnote 38 Operetta is a textbook case of the theatrical lineage of television, since – unlike for opera – the link between the two media is immediate and repeatedly acknowledged, albeit obliquely.

Frattini’s introductory article for the 1954 broadcast of Al cavallino bianco includes an anecdote about a retired officer being roped in by the brothers Schwarz to play the Archduke in their production of Benatzky’s work at their Femina Theatre. In Frattini’s probably fanciful reconstruction, ‘two months ago, when Al cavallino bianco was staged in Trieste, the director Luciano Ramo, who had been an enthusiastic collaborator of Schwarz, invited the old officer to don the Archduke’s uniform once more’.Footnote 39 Two photographs accompany this text: the first a studio portrait of Rosy Barsony, who played Ottilia, and another of Barsony and Nuto Navarrini (Zanetto Pesamenole) sitting at a table.Footnote 40 The latter is certainly not from the TV programme, since both actors wear costumes different from those seen in it. Rather, it seems to have been taken in a theatre, especially because its angle is from below and the actors seem to be on a stage. My suggestion is that this photograph comes from the production of Al cavallino bianco that was staged precisely two months earlier in the courtyard of Trieste’s Castle of San Giusto with Barsony as Ottilia and Navarrini as Pesamenole. The direct filiation of October’s TV programme to August’s theatrical production is proven beyond doubt by the rest of the cast, which, besides Barsony and Navarrini, included in both instances Elvio Calderoni as Leopoldo, Gualtiero Rispoli as Sigismondo, Glauco Scarlini as Giorgio, Franz Steinberg as Hinzelmann, Anna Campori as Claretta and Laura Silli as Kathi. Among the protagonists, only Gioseffa, the soprano (which in this case means the sentimental female lead, as opposed to the comic soubrette, here Barsony), was different: Nora Enjon in Trieste, Edda Vincenzi on television.Footnote 41

Frattini brings up another Triestine connection in the introductory article to the February 1955 broadcast of Sogno di un valzer. In his words, this operetta ‘keeps intact its freshness and its appeal, as demonstrated last year by a new production by Luciano Ramo for Trieste’s Operetta Festival: a big success and sold-out performances’.Footnote 42 The overlap between the cast of the Trieste production of August 1954 and the one for the TV broadcast of February 1955 is not as extensive as in the case of Al cavallino bianco, but it is still sufficiently substantial to prove a direct connection: Edda Vincenzi (Franzi), Vittoria Palombini (Federica), Elvio Calderoni (Lotario), Anna Campori (Fifi) and Gualtiero Rispoli (un generale).Footnote 43 For both Sogno di un valzer and Al cavallino bianco, however, the most significant recurring name is that of the conductor, Cesare Gallino, who had been a fixture of Trieste’s Operetta Festival from its inception in 1950 – when he had conducted an earlier production of Al cavallino bianco (with a completely different cast except for Rispoli) and La vedova allegra – and would go on to lead all the broadcasts of the 1954–5 operetta season except La vedova allegra, and indeed most TV broadcasts of operetta until the 1970s.Footnote 44

The case of Gallino brings up another potentially relevant media context, since he had been a fixture of Italian radio almost since its inception. He conducted hundreds of broadcasts of ‘light classics’ and operetta between 1929 – his very first programme was Lehár’s La mazurka bleu (Die blaue Mazur) on 13 July of that year – until 1949, when for some reason he disappeared from RAI until 1954. Over that year he conducted several potpourri concerts until October, when, almost at the same time as the beginning of the TV operetta broadcasts with Al cavallino bianco, he resumed operetta on the radio as well, leading performances of No, no, Nanette (6 October), Scugnizza (13 October), Al cavallino bianco (20 October), Lehár’s Eva (3 November) and Il barone di Corbò, a ‘musical comedy’ by Luigi Antonelli and Virgilio Fucile (26 December, repeated on the 28th). Radiocorriere’s listing of other performers in these radio broadcasts is inconsistent, but not a single one of the names reappears in the cast lists for the operetta programmes on television, not even for two transmissions of Al cavallino bianco that were almost contemporaneous, on 14 and 20 October (TV and radio, respectively). We must conclude, then, that the TV operetta season of 1954–5 exhibits direct links with contemporary theatrical practice, but, except for Gallino, none with contemporary radio.

The reasons for this lack of continuity between the two media – which after all were managed by the same institution, RAI – are certainly diverse. The most relevant to us is that the actors and singers who regularly performed operetta on the radio – often listed separately in Radiocorriere, making it clear that those who sang did not also speak the dialogue – were deemed ill-suited to the radically different demands placed on performers by television. These demands could be met far more effectively by theatrical performers, especially those specialised in rivista, like Giusti, or operetta, like the troupe that brought their Cavallino and, in part, their Sogno di un valzer from the courtyard of the Castle of San Giusto in Trieste to the radically different environment of Milan’s RAI studios. The matter of Trieste, however, requires further exploration – a final detour that will lead us back to politics, and to the long-contested Italianness of operetta itself.

North by northeast

In the mid- and late twentieth century, Trieste – located at the easternmost point of northern Italy, very close to the present-day border with Slovenia – was considered Italy’s city of operetta; perhaps it still is, insomuch as operetta elicits any consideration at all in present-day Italy. Reconstructing the genealogy of this association is far from easy, but two factors seem especially relevant. The first is that Trieste was part of the Habsburg Empire until 1918, and therefore had strong links with everything Viennese, including operetta, performed in German, Italian and Slovene: to name just one event, in 1907 Lehár himself conducted the first local performance of Die lustige Witwe (in German, naturally). These links evidently continued after World War I, as suggested by the thriving operetta culture in the city: for example, in 1936 Lehár conducted his Der Zarewitsch, while in 1938 Richard Tauber sang in his Das Land des Lächelns and in Das Dreimäderlhaus with the company of the Vienna Volksoper on tour. These connections extended to the surrounds of Trieste as well: most interestingly a dedicated festival was held in the then-Italian town of Abbazia (now Opatija) between 1935 and 1938, which was promoted by Lehár and also saw the presence of Kálmán, Tauber and Barsony among other stars. The second factor in this genealogy is the aforementioned Operetta Festival, which was founded in 1950 and has continued until today (albeit with several and sometimes long interruptions, for example during the whole of the 1960s).Footnote 45 In the mid-1950s, then, Trieste was the obvious place to turn for anything related to operetta. RAI did precisely this, as we have seen, and continued to do so until at least the end of the decade: its first TV broadcast of a theatrical performance of an operetta – as opposed to the studio productions of 1954–5 – was Lehár’s Frasquita from the Castle of San Giusto, where it was staged in 1958 by none other than Molinari, who also directed the broadcast.Footnote 46

In 1954, however, any mention of Trieste (or even any implicit reference to it) had political undertones. After Italy’s defeat in World War II the city and its surroundings were occupied by both Yugoslav and Allied troops. In 1947 the Treaty of Paris between Italy and the Allied nations established the Free Territory of Trieste, an independent entity divided into two zones: A, controlled by British and American forces (which included Trieste proper), and B, controlled by Yugoslav ones. The following years saw widespread unrest, mainly by local Italian-speaking people who considered themselves Italians pushing for the reunification of Trieste with Italy, which caused significant loss of life, especially during the so-called ‘revolt of Trieste’ in November 1953, when six people were shot dead by the British police. It was precisely this ‘revolt’ that ultimately led to the London Memorandum, signed on 5 October 1954 by the American, British, Italian and Yugoslavian governments, according to which the A zone was assigned to Italy and the B zone to Yugoslavia.

References to the ‘Trieste question’, as it was known at the time, are by no means unknown in Italian music of these years. A sentimental ballad about a lovers’ reunion entitled ‘Vola, colomba bianca, vola’ (‘Fly, white dove, fly’) whose text includes allusions to Trieste – ‘San Giusto’ (the city’s patron saint); ‘we left the shipyard’ (Trieste’s shipyards are famous); ‘il mio vecio’ (‘my old man’ in northeastern dialect) – won the 1952 edition of the Sanremo Song Festival and went on to become one of the most famous Italian songs of the twentieth century. In a brief interview during the live radio broadcast of the Festival, its interpreter, Nilla Pizzi, sent her greetings to ‘mum, dad, my sisters and [a meaningful pause] Trieste’; the presenter, Nunzio Filogamo, replied ‘brava! you are right’, to the live audience’s applause.Footnote 47

The case of TV operetta is of course less straightforward. I am certainly not claiming that broadcasting operetta on television was RAI’s way of joining the clamour for an ‘Italian Trieste’ or celebrating the city’s return to Italy – when the decision to programme Al cavallino bianco was taken, presumably during the summer of 1954, the London Memorandum had not yet been signed. It is worth pointing out, though, the close chronological contiguity between the signing of the Memorandum on 5 October, the TV broadcast of Benatzky’s work on 14 October, the widely publicised entry of the first Italian troops in Trieste on 26 October, the no less emphatically advertised visit to the city of the Italian President Luigi Einaudi and the Prime Minister Mario Scelba on 5 November, and the TV broadcast of La casa delle tre ragazze on 9 November. Trieste was already associated with operetta at the time, and there was an acknowledged connection between the local production of Al cavallino bianco in August and its TV broadcast in October. It is tempting therefore to link the avowedly triumphant arrival of operetta on the new medium (a medium tasked with building a modern Italy) with the no less triumphant return of Trieste (its ‘second liberation’ after the 1918 liberation, according to widespread media rhetoric) to this same Italy. The restoration of Trieste to Italy was hailed in some quarters as the final act of the long Risorgimento, the nation-building process that had started in the previous century.

The Italy of 1918 welcoming Triste into its fold and the Italy of 1954 welcoming it back were hugely different, though. In 1954, any emphatic nationalist rhetoric ran the real risk of sounding fascist, since fascism had made fanatical nationalism a pillar of its ideology. Witness the manoeuvring of the Settimana Incom newsreel of 30 October 1954, entitled ‘W Trieste italiana’, whose voice-over speaks of ‘a picture from fifty years ago’: ‘Trieste is outside the fast, sceptical world of today, it is out by at least half a century; it’s like a romantic island where the poetry of love for the fatherland is still alive, the old way … like early in the century. The city is frozen in time, it’s still in the years of the Risorgimento.’Footnote 48 In this description, Trieste comes to sound almost like the setting of a Silver Age Viennese operetta: an idyllic, isolated spot where time seems to have stopped. Fascism was explicitly excised from this official discourse of nostalgia, then, in contrast to RAI’s institutional rhetoric of nostalgia for the happy old world of operetta discussed above, where it creeps in through the emphasis on order, innocence and dignity, implying continuity with its reference to the older generation, who was still very much around and sure to enjoy the operetta programmes. The difference is of course that the discourse of Trieste was infinitely more politically charged than that of operetta, and therefore needed handling with extreme care, lest nostalgia be accused of breeding nostalgici.

How, then, to assess operetta’s potential political dimensions in 1954 Italy, when it made its trumpeted entry into (some) Italian houses thanks to television, in light of these Triestine connections? Might the Triestine aura of the genre as well as the actual Triestine derivation of some of the TV broadcasts function as yet another link to old times? And if so, which times exactly? The recent past of fascist Italy or the more remote one when Trieste ‘finally became Italian’ in 1918? And what of operetta’s Viennese lineage, bolstered by the provenance of the majority of the works broadcast, explicitly and repeatedly mentioned in RAI’s official discourse, and further evoked by Trieste’s Habsburg past, particularly evident in its still thriving operetta culture? Anything ‘German’ – which included Austria and Vienna – provoked complex feelings in Italy following World War II given the massive effort on the part of Italians to distance themselves and their fascist past from Nazi Germany, given the atrocities carried out by the occupying German army – together with the Italians still faithful to Mussolini – in central and northern Italy between 1943 and 1945, and given the anti-German and anti-fascist Resistance of those years, on which the Italian Republic declared itself to be built.

Further aspects relevant to this complex issue emerge if we return one final time to matters of casting, specifically for the final TV broadcast, which was La vedova allegra on 7 May 1955. There is a sense that RAI wanted its first operetta season (and, as it would turn out, the last under that designation) to go out with a bang, not only by saving the most famous work of them all until last, but also by casting it particularly lavishly. Danilo Danilowitch was tenor Gino Mattera, who had had prominent engagements at the Rome Opera among other theatres (including as Almaviva in Il barbiere di Siviglia and Alfredo in La traviata) but had also starred in a number of opera-related films of the late 1940s and early 1950s – and who had already featured in the broadcasts of Il paese dei campanelli and Sogno di un valzer. Camillo de Rosillon was tenor Ezio De Giorgi, whose career profile was similar to Mattera’s if less prominent, and who had also already been on TV, as Rinuccio in RAI’s Gianni Schicchi in January of that same 1955 – an exceedingly rare instance of a singer appearing in both opera and operetta television broadcasts in 1954–5. By far the two most prominent stars, though, were Erminio Macario, a famous comic actor who had been a staple of rivista since the 1920s and had starred in several film comedies from the late 1930s onwards, who played the Njegus – and above all, Hilde Güden as Anna Glavari.

Having started her career as an operetta singer in the late 1930s, Güden was by the mid-1950s one of the brightest stars of the Vienna State Opera, where she had been a company member since 1947. She was also internationally renowned, having also sung at the Salzburg Festival, Covent Garden, La Scala, other Italian theatres and the Metropolitan Opera in New York (where she had been Anne Truelove in the American premiere of Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress in 1953). She had also featured on several studio recordings, including a Rosenkavalier (as Sophie, with the Vienna Philharmonic under Erich Kleiber) and a Rigoletto (as Gilda, with Rome’s Santa Cecilia Orchestra under Alberto Erede), both in 1954 for Decca. What on earth was she doing singing and speaking in Italian on RAI television? Secondary literature on Güden is scant, but it emerges that between 1942 or 1943 and 1947 she was based in Italy – first in Florence, then in Milan – having fled Munich (where she was a member of the ensemble at the Bavarian State Opera) because she was alleged to be Jewish (she claimed that she was not) and was accused of espionage.Footnote 49 Her precise whereabouts during these years are presently unknown, but it seems quite astonishing that she could live and perform in Nazi-dominated central and northern Italy between 1943 and 1945 after escaping Nazi Germany (although she held Turkish citizenship thanks to a brief marriage to a Turkish man before the war). In any case, it was evidently during those years that she learnt Italian well enough to speak it live on television.

That same Vedova allegra also featured the aforementioned Navarrini, by then a staple of the RAI operetta season, as Baron Zeta. He was one of the numerous performers who had not only extended their reach from theatre to television, but also begun their careers during the fascist ventennio. Unlike his colleagues, however, he was infamous as a fervent fascist and, worse, a committed repubblichino. He had sung anti-Resistance and anti-Allies songs in rivista productions under the Italian Social Republic (the puppet state created in northern Italy by the Nazis after the fall of fascism on 25 July 1943 and Italy’s armistice with the Allied nations on 8 September that same year), for which he was rewarded with honorary membership by the ‘Xa MAS’, an ‘elite’ military unit notorious for atrocious crimes against partisans. Navarrini was arrested soon after the end of the war, held in Milan’s San Vittore prison and eventually tried. He was acquitted – supposedly for lack of evidence – but his return to the stage in late 1945 and early 1946 was met with vehement remonstrations.Footnote 50 By the 1950s, though, he had evidently not only regained his prominent position in theatres, but had also been enrolled by television to participate in its attempt to return operetta to its past glories. Thus, a person who suffered at the hands of the Nazis (Güden) performed next to another (Navarrini) who had publicly backed them and their Italian supporters, contributing repeatedly to a climate of hatred that led to unspeakable violence and a horrifying number of deaths, precisely through theatrical performance in a genre contiguous to that which brought these two persons together in a RAI television studio in 1955. A situation such as this, hardly unheard of in the postwar years in those European countries that had seen a Nazi–fascist presence, constitutes a clear symptom of the complicated personal and institutional negotiations required by certain forms of continuity at work in postwar Italy and other such countries, and which remain at the centre of historiographical debate.Footnote 51

Forgetful nostalgia

The case of Güden and Navarrini in La vedova allegra can usefully serve as starting point for some conclusions. For one, it throws a different, rather colder light on the cosy discourse of nostalgia through which RAI advertised its 1954–5 operetta season. This nostalgia appears to be promoting, or at least be dependent on, a certain selective forgetfulness, not to say amnesia, on the part of various people and institutions.Footnote 52 One wonders, for example, how Güden remembered the years she spent in Italy during and immediately after the war, and which memories surfaced when she found herself speaking Italian on Italian television (which may well have been her first TV appearance). Did she know about Navarrini’s activities during those same years? Did the other performers? It seems unlikely that RAI did not, but perhaps his Triestine credentials helped erase his past from institutional memory. Did it not cross anybody’s mind, though, that the good old times when operetta was still popular in Italy meant the times when this same Italy was in the grip of a violent totalitarian regime that inflicted the tragedy of World War II on the country, with its legacy of death, destruction, suffering and horror? And that some supporters of that regime involved in the operetta broadcasts might be nostalgici for it? And if it did cross somebody’s mind, which feelings did it stir?

Another concluding reflection suggested by the case of La vedova allegra concerns the heterogeneity of casting for the TV operetta season. The few cases I have presented here suggest that performers came from different genres – first among them operetta of course, but also rivista, spoken comedy and opera – and different media, including theatre and film (but almost never radio, except for the conductor Gallino). Additional cases would include other genres and media – popular music and the phonograph record – and deepen the perspective on those already mentioned. La vedova allegra, for instance, was conducted by Bruno Maderna, who had already attended Darmstadt’s Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik and composed several avant-garde works (and, incidentally, had been a member of the anti-fascist Resistance). What is more, compared to the casts of the operas broadcast from the RAI TV studios at that time, those of the operetta season – perhaps unexpectedly – seem to include more older people, several among whom were well established already in the 1930s and even in the 1920s in some cases. Operas relied on younger performers, who had rarely had any meaningful career in the pre-war years: to name just two indicative cases, Violetta in a 1954 Traviata was 24-year-old soprano Rosanna Carteri, and even an old man like Donizetti’s Don Pasquale was performed in 1955 by 40-year-old bass Italo Tajo.

The matter of age and generation is relevant not only for the performers, but also for the public, as we have seen. RAI’s rhetoric of nostalgia was obviously directed at the older generation, who may have indeed seen those older artists in live operetta or rivista performances before and during the war. Much more could be said about RAI’s discourse of operetta’s cross-generational appeal, which, in the context of the initial stirrings of a ‘youth’ musical culture in Italy in the mid 1950s, highlights by contrast an emerging generational divide in musical tastes and consumption. Unfortunately, the audience surveys that RAI published starting in 1957 include questions on operetta broadcasts only from 1959: the first, from late 1959, covers transmissions between January 1957 and June 1959 and therefore excludes the 1954–5 operetta season. What seems likely, in any case, is that the success of that initial operetta season was perhaps not as ringing as RAI claimed, and that television’s rescue operation may not have given the old genre the desired boost, given that after 1955 operetta completely disappeared from the screen for a few years, returning from 1958 mostly in the form of ‘selections’ lasting about one hour and fifteen minutes. The difference from opera is once again blatant, since the latter continued to be broadcast regularly from the RAI studios until 1957, after which relays from theatres progressively took over – operetta was almost never relayed from theatres after that initial experiment with Frasquita from Trieste mentioned above.

Yet another difference from opera was that operettas were systematically subjected to revisions and rewritings for television, even for the 1954–5 season when they were not necessarily shortened, while operas were never tampered with. The matter was discussed only once by Radiocorriere, in an article by humourist writer Achille Campanile exposing the reasons why he basically re-wrote the libretto of La principessa della czarda. Footnote 53 Yet the textual status of operettas was – and indeed often still is – very weak, with not only dialogue being constantly changed and partly improvised, but musical numbers easily coming and going. How to discuss the changes made for RAI without knowing the texts against which they were made? As for the political, technological and casting angles that I have explored here, taken together they highlight the resistance of operetta to being subsumed into grand narratives of progress dominating 1950s Italy, as well as adding a new perspective on the relationship between nostalgia, sentiment and political engagement – or, better, ostensible political escape – that has guided much writing on operetta to date. In this Italy, operetta, which – let’s not forget – had come into being in order to fill the middle musical–theatrical ground left open by the ever-rising cultural trajectory of opera, and which therefore had in-betweenness written in its DNA, was precariously perched on fault lines that are not only cultural, social and political, but also technological and medial.

In a crucial sense, television’s ostensibly generous gesture of taking up operetta in order to give it a life-saving injection ended up only highlighting operetta’s marginality in the socio-cultural context of 1950s Italy. The premiere of the (by then) octogenarian Carlo Lombardo’s final work, Diavolo e jazz, in 1954 prompted journalist Massimo Alberini to point out that the genre remained popular mostly in the southern regions, while ‘the sceptical North’ had left it behind.Footnote 54 The North–South division was – and in part still is – an economic, social and cultural one, with the mostly rural and poorer South less ‘advanced’ and ‘modern’ than the industrial, richer North. By the 1950s, then, operetta was perceived as backward-looking not only in chronological terms but also in geographical ones. What is more, early television was accessible predominantly in the northern and central regions, while its availability in the South was spotty at best. Made primarily in Milan, the capital of the North, it carried with it the city’s reputation for progress and dynamism. The northern middle classes, for which operetta had been so important in the early decades of the century, had moved on to other forms of musical theatre. More importantly, television was already in the process of revolutionising the modes of consumption of the performing arts, transforming theatregoing from an unmarked habit into an occasional rite. It was precisely as a rite that it could still to some extent encompass opera – although attendance of opera performances was itself negatively affected by the arrival of television. In any case, opera enjoyed an immensely higher cultural prestige, making its presence on television a matter of course. Operetta did not even come close to opera in this respect, and therefore its encounter with television was much more fraught.

It might have been precisely television’s discourse of nostalgia for operetta, with the selective forgetfulness that it necessarily entailed, that ended up sealing the fate of operetta itself on television, or at least spotlighting its marginal status in the cultural landscape of a nation that desperately wanted to think of itself as new, especially on that newest and most modern of media, television. Operetta as a nostalgic walk down memory lane necessarily sat uncomfortably with this cultural, but also psychological and emotional orientation. It brought back the memory of ‘twenty years ago’, which is to say fascism and all it had entailed: violence, oppression, war, destruction. The collective sentiment about all this was shame, and who wants to feel ashamed? Other forms of entertainment such as rivista were too tightly imbricated in the cultural fabric of Italian society to be thus cast aside: most important for the issues that I have discussed here, they were not perceived to be irredeemably enmeshed with the past, nor of course were they promoted as such, and therefore their consumption, including their presence on television, did not cause shameful memories to return. If the 1954–5 operetta season represented a world coming back, then, at stake was not only the question of which world exactly, as I have discussed above, but whether the very act of coming back was in any way desirable in the context of a society that wanted most of all to forget, to look ahead to a future that in 1950s Italy seemed very bright – a future promised nowhere more loudly and triumphantly than on television. Whatever world was supposedly coming back could keep itself to itself, and stay where a terrible war had rightly confined it: in the past.

Acknowledgements

Research for this article was mostly undertaken during my time as Leverhulme Visiting Professor at the University of Cambridge between January and June 2023; an earlier version of parts of it was presented as a Leverhulme lecture at the Cambridge Faculty of Music in May. I am very grateful to Benjamin Walton for sponsoring my visit to Cambridge and to Damien Pollard for his insightful and stimulating response to the lecture.