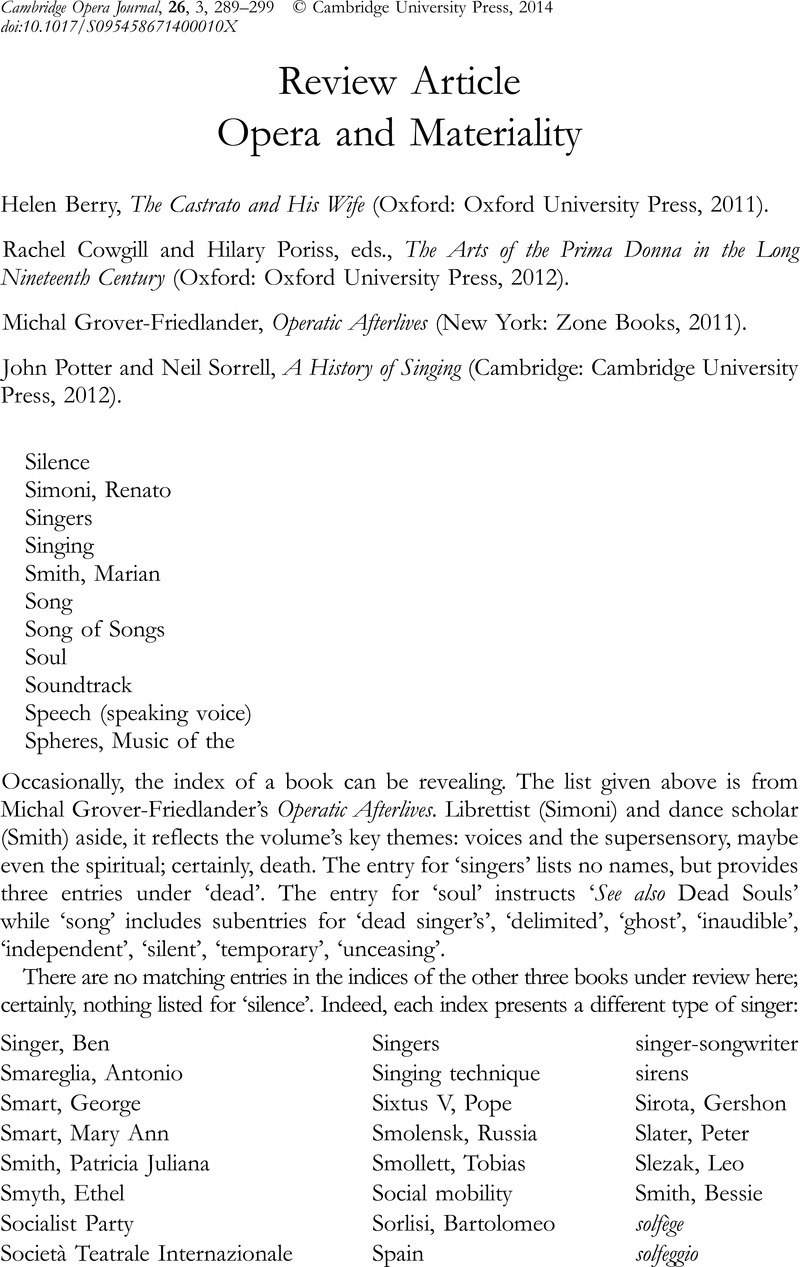

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 October 2014

1 Till, Nicholas, ‘Introduction: Opera Studies Today’, in The Cambridge Companion to Opera Studies, ed. Till (Cambridge, 2012), 1–24CrossRefGoogle Scholar; here 2.

2 Julian Rushton’s chapter in The Arts of the Prima Donna provides a considered overview of recent approaches to opera in performance; see ‘The Prima Donna Creates’, 115–20.

3 For more on the ‘romance’ of critical editions see Gossett, Philip, Divas and Scholars: Performing Italian Opera (Chicago, 2006), 133–165CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

4 Poizat, Michel, L’Opéra, ou le Cri de l’ange: Essai sur la jouissance de l’amateur de l’opéra (Paris, 1986)Google Scholar was published in a translation by Arthur Denner as The Angel’s Cry: Beyond the Pleasure Principle in Opera (Ithaca, 1992). See also Clément, Catherine, Opera, or the Undoing of Women, trans. Betsy Wing (Minneapolis, 1988)Google Scholar; and Dolar, Mladen, ‘The Object Voice’, in Gaze and Voice as Love Objects, ed. Renata Salecl and Slavoj Žižek (Durham, NC, 1996), 7–31Google Scholar.

5 Key texts include Abbate, Carolyn, ‘Opera; or, the Envoicing of Women’, in Musicology and Difference: Gender and Sexuality in Music Scholarship, ed. Ruth A. Solie (Berkeley, 1993), 225–258Google Scholar; and her Unsung Voices (Princeton, 1991); and Smart, Mary-Ann, ed., Siren Songs: Representations of Gender and Sexuality in Opera (Princeton, 2000)Google Scholar.

6 Abbate, Carolyn, ‘Music – Drastic or Gnostic?’, Critical Inquiry 30 (2004), 505–536Google Scholar.

7 Abbate, Carolyn and Parker, Roger, A History of Opera: The Last Four Hundred Years (London, 2012), 7–8Google Scholar.

8 See Epping-Jäger, Cornelia and Linz, Erika, ‘Einleitung’, in Medien/Stimmen, ed. Epping-Jäger and Linz (Cologne, 2003), 7–15Google Scholar; quoted in Duncan, Michelle, ‘The Operatic Scandal of the Singing Body: Voice, Presence, Performativity’, Cambridge Opera Journal 16 (2004), 283–306CrossRefGoogle Scholar; here 284.

9 Duncan cites as examples Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey (Stanford, 2004); Gumbrecht, , ‘Produktion von Präsenz, durchsetzt mit Absenz. Über Musik, Libretto and Inszenierung’, in Ästhetik der Inszenierung, ed. Joseph Früchtl and Jörg Zimmermann (Frankfurt am Main, 2001), 63–76Google Scholar; and Abbate, ‘Music – Drastic or Gnostic?’

10 In this she builds on her first monograph, which asserted that silent film allows opera to move past Poizat’s ‘cry’, towards what lies beyond song and vocal expression: silence. See Vocal Apparitions: The Attraction of Cinema to Opera (Princeton, 2005), 21.

11 David J. Levin has been particularly influential here, both through his own writing and as editor of Opera Quarterly: see his Unsettling Opera: Staging Mozart, Verdi, Wagner, and Zemlinsky (Chicago, 2007).

12 Kreuzer, Gundula, ‘Wagner-Dampf: Steam in Der Ring des Nibelungen and Operatic Production’, Opera Quarterly 27 (2011), 179–218CrossRefGoogle Scholar; here 180–1.

13 Gordon, , ‘A Note from the Guest Editor’, Opera Quarterly 27 (2011), 1–3CrossRefGoogle Scholar; here 1.

14 Kreuzer, ‘Wagner-Dampf’.

15 John Potter suggests that, contrary to our modern assumption, ‘perhaps born of the experience of generations of church-educated trebles’, that ‘it was a boy’s voice projected into adulthood’, it seems more likely that ‘the androgynous sound that so bewitched audiences might better be thought of as more of an ungendered child’s voice’, akin to the light sopranos of the early nineteenth century: ‘Sontag, Lind and Patti, may have touched the same nerve as that of their mutilated male predecessors’; A History of Singing, 120.

16 Mission (Decca, 2012) does gesture towards the historically informed, but in an offbeat way: Bartoli duets with French counter-tenor Philippe Jaroussky and is accompanied by the Swiss period orchestra I Barocchisti.

17 Leon, Donna, The Jewels of Paradise (London, 2012)Google Scholar, 3, 56.

18 Leon, , The Jewels of Paradise, 79Google Scholar.

19 Rutherford, Susan, The Prima Donna and Opera, 1815–1930 (Cambridge, 2006)Google Scholar, 2.

20 Currie describes his essay as ‘a bit of a prima donna’. The next essay, by Julian Rushton, begins with a dictionary definition: ‘someone difficult to please, especially someone given to melodramatic tantrums when displeased’, 111 and 115.

21 Sophie Fuller, ‘“The Finest Voice of the Century”: Clara Butt and Other Concert-Hall and Drawing-Room Singers of fin-de-siècle Britain’, 308–27.

22 See, for example, Gurminder Kaur Bhogal’s consideration of the original Lakmé, American soprano Marie van Zandt, and the titular opera’s textual origins and exoticism: ‘Lakmé’s Echoing Jewels’, 186–205.

23 Jonathan Dunsby bemoans the granular turn in popular music studies in ‘Roland Barthes and the Grain of Panzéra’s Voice’, Journal of the Royal Musical Association 134 (2009), 113–32.