No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

Abstract

- Type

- Other

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge Law Journal and Contributors 1931

References

11 A discussion then followed as to the terms of a stay.

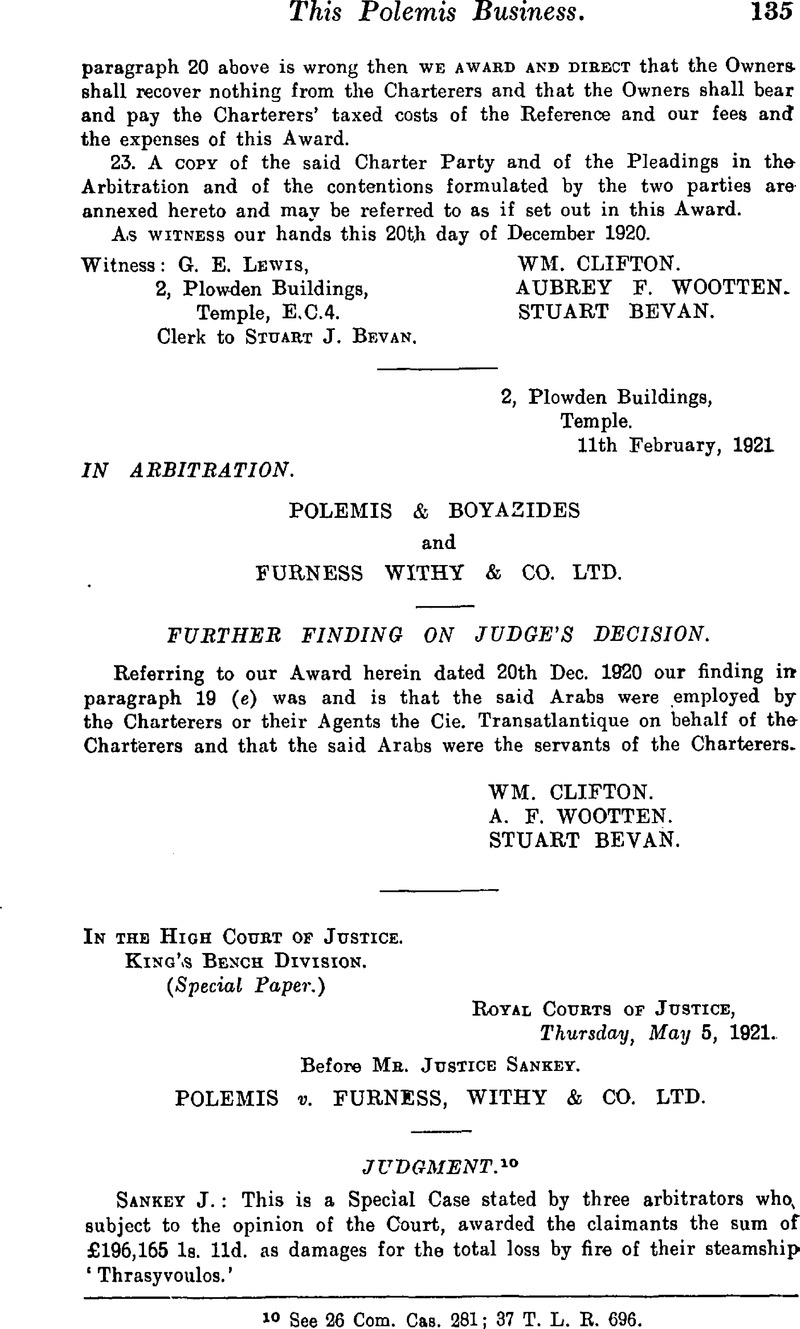

12 [1921] 3 K. B. 560.

13 Amounting, together with some incidental loss, to £196,000.

14 At pp. 574, 575.

15 The learned editors of the 17th edition of Anson, , ‘Law of Contracts’ (1929)Google Scholar (Miles and Brierly) do not mention the Polemis Case (quite rightly, I submit). In Chitty's Law of Contracts (18th ed. 1930) (Macfarlane and Wrangham), at p. 953, the Polemis Case is treated as relevant to the measure of damages for breach of contract and as qualifying or explaining Hadley v. Baxendale. In Mayne on Damages (10th ed. 1927) (Gahan), passim, the Polemis Case is treated as relevant to tort and breach of contract alike but not as disturbing Hadley v. Baxendale. The decision of the Privy Council in Great Lakes Steamship Co. v. Maple Leaf Milling Co., Ltd. (1924) 41 T. L. R. 21, though the Polemis Case is not mentioned, deserves notice.

16 [1925] 1 K. B. at p. 164.

17 Salmond & Winfield, ‘Law of Contracts’ (1927), pp. 506, 507.

18 ‘Law of Torts’ (13th ed. 1929), pp. 32—41, et passim.

19 (1854) 9 Exch. 341.

20 At p. 38, and see the following extract from the Preface: ‘My learned friend Prof. Winfield's discovery that the doctrine laid down in Polemis' Case was, in its application to the cause of action before the Court of Appeal in that case, in conflict with the rule in Hadley v. Baxendale is noted at pp. 37—39.’ I think that Professor Winfield's language is somewhat more guarded than this comment would suggest.

21 Op. cit. at p. 582.

22 See Pollock, op. cit. at p. 560: ‘But injury which would have been a tort, as breach of a duty existing at common law, if there had not been any contract, is still a tort,’ citing Taylor v. Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire Ry. Co. [1895] 1 Q. B. 134, and see particularly A. L. Smith L.J. at p. 140.

23 [1921] 3 K. B. 560.

24 (1854) 9 Exch. 341.

25 In Hammond & Co. v. Bussey (1887) 20 Q. B. D. at p. 87.

26 See Pollock, op. cit. at p. 38.

27 Per Alderson B., at p. 354.

28 And therefore, I submit, within the contemplation of the ordinary reasonable man.

29 The expression ‘naturally, i.e. according to the usual course of things’ means, it is submitted, what normally happens ‘in the great multitude of [similar] cases,’; and probably will happen in the case under consideration (see Alderson B. loc. cit.). ‘Natural’ here clearly cannot be used in the literal sense—see Sumner, Lord in Weld-Blundell v. Stephens [1920] A. C. at p. 983Google Scholar: ‘Everything that happens, happens in the order of nature and is therefore “natural.”’ If that is all that ‘natural’ meant in Hadley. v. Baxendale, it would be meaningless.

30 It may sometimes be objective, as in Cory v. Thames Ironworks Co. (1868) L. R. 3 Q. B. 181.

31 See Blackburn J. in Cory v. Thames Ironworks Co., supra, at p. 190: The measure of damages when a party has not fulfilled his contract is what might reasonably be expected in the ordinary course of things to flow from the non-fulfilment of the contract, not more than that, but what might be reasonably expected to flow from the non-fulfilment of the contract in the ordinary state of things, and to be the natural consequences of it. The reason why the damages are confined to that is, I think, pretty obvious, viz., that if the damage were exceptional and unnatural damage, to be liable for that would be hard upon the seller, because if he had known what the consequences would be he would probably have stipulated for more time, or, at all events, have used greater exertions if he knew that that extreme mischief would follow from the non-fulfilment of his contract.' This passage brings out well the mental element in the measure of damages for breach of contract. ‘Natural’ is clearly used in the sense of ‘probable,’ ‘normal,’ ‘to be expected.’

32 E.g. Brett M. R. in The Notting Hill (1884) 9 P. D. at p. 113; Bowen L.J. in Cobb v. Great Western Rly. Co. (1893) 62 L. J. Q. B. at p. 337, cited by Summer, Lord in Weld-Blundell v. Stephens [1920] A. C. at p. 979.Google Scholar

33 Which is very far from being a simple one in view of the tortious origin of the action of assumpsit which as Sir Pollock, Frederick says (‘Law of Torts’ (13th ed.) (1929), at p. 555)Google Scholar ‘from a variety of action on the case … had become a perfect species, and in common use its origin was forgotten.’

34 I am glad to find that the learned editor (Stallybrass) of the seventh edition of Salmond's, ‘Law of Torts’ (1928) (see p. 157Google Scholar, note 2) is also of the opinion that Hadley v. Baxendale is not overruled by Re Polemis.