Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 December 2011

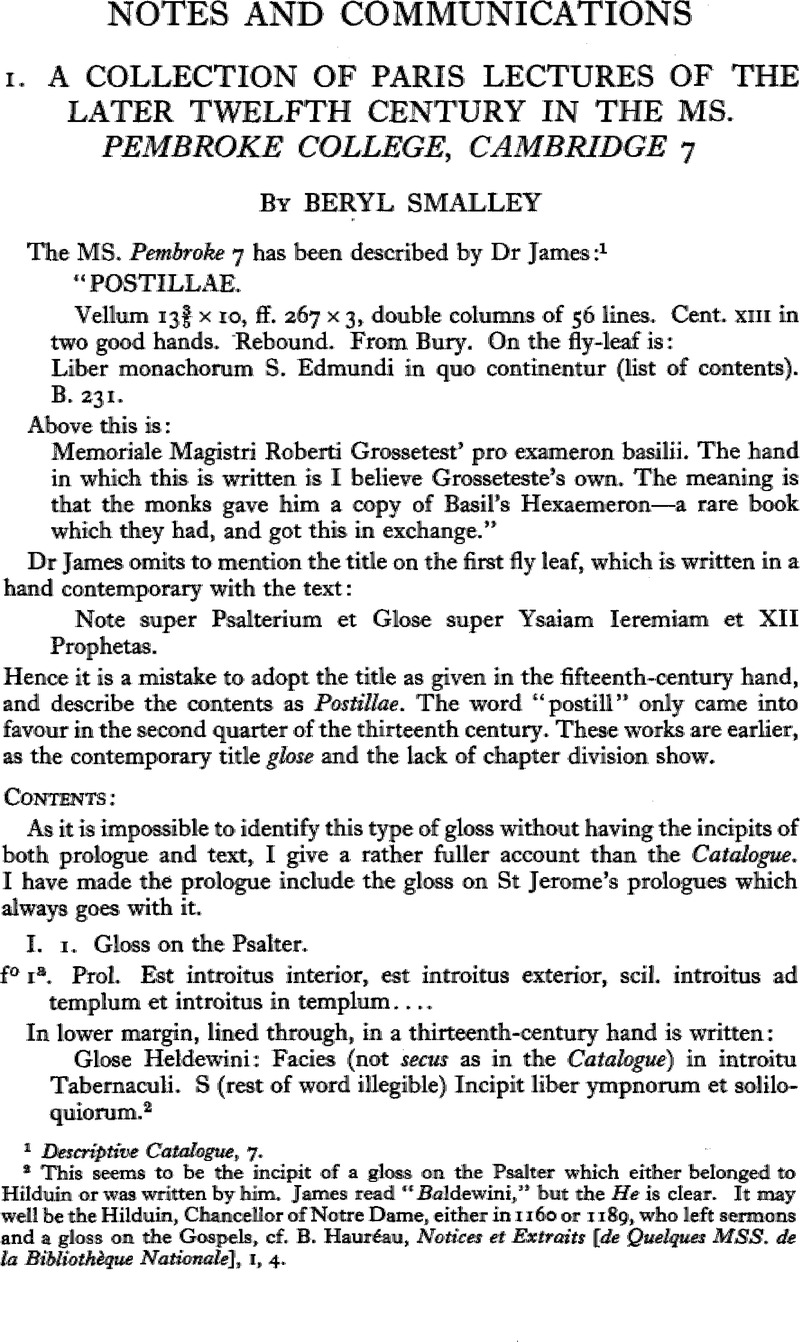

1 Descriptive: Catalogue, 7.

2 This seems to be the: incipit of a gloss on the Psalter which either belonged to Hilduin or was written by him. read, James “Boldewini,”Google Scholar but the He is clear. If may well be the Hilduin, Chancellor of Notre Dame, either in 1160 or 1189, who left sermons and a gloss on the Gospels, cf. Hauréau, B., Notices et Extraitt [de Quelques MSS. de la Bikliatftique Nationale], I, 4Google Scholar.

3 Cat[alogi] Vet[eres] (Surtees Soc), 1838, 121Google Scholar: Item, statutum est per eosdem lit nullus Liber accomodetur alicui per Libntrium, vel per alium, nisi, reoeperit memoriale aequipollens….

4 M, R. James, The Abbey of Si Edmumd at Bury, Cambridge, 1895, I, The LibraryGoogle Scholar.

5 Cf. Ghellinck, J. de, Le Moumment Théohgique du XIIe Siécle, Paris, 1914, 256–7Google Scholar. James, M. R., “Robert Grosseteste on die Psalms”, Journal of Theological Studies, XXIII, 1921, 183–5Google Scholar.

6 Cf. Ogilvy, J., Books known to Anglo-Latin Writersfrom Aldkelwi to Aladn (Mediaeval Academy of America), 1936, 21Google Scholar; Cappuyns, M., Jean Scot Engine, Louvain, 1933, 48, 146Google Scholar.

7 For instance:, Durham, Cat. Vet. 59; Boston, found, it at Ramsey, Registnan, MS. Add. 3470 of Cambridge University Library, 44; but it does not appear in the catalogues of Christ Church and. St Augustine's, Canterbury, published by M. R. James, Ancient Libraries of Canterbury and Dover, Cambridge, 1903. There were copies at Corbie, Cluni, St Martial of Limoges, Marchiennes, cf. L. Delisle, Cabinet ties MSS., 11, Paris, 1868, 42.9, 461, 497, 5:1,4.

8 Cf. Gorce, D., Lectio Dhiina, Paris, 1935Google Scholar.

9 Cf. Paré, G.Brunei, A. and Tiembiay, P., La Renaissance [du XIIe Siécle], Paris, Ottawa, 1933, 240–7Google Scholar. The use of excerpts was not peculiar to the twelfth century; but: it tended, to be standardized.

10 Stephen Langton. on the Pauline Epistles and the Prophets gives some good examples of this practice Lacombe, G. and Smalley, B., “Studies [on, die Commentaries of Cardinal Stephen Langton]”, Archives d'histoire doctrinale et littéraire du moyen age, V, 1931, 59Google Scholar: “The Lombard's Commentary on Isaias [and Other Fragments”], The New Scholasticism, 1931, 131–2Google Scholar. On the term originalia see La Renaissance, 251–8.

11 I have looked through the copy in, MS. Royal 6 E. v, fo 136–40. Several scholars are working on Grossetéte's exegesis. They have not yet proposed a date for die treatise, but probably it belongs to his teaching period, before he became bishop of Lincoln, 1235.

12 , Cronica, Mem[orials of] St. Edmmd's [Abbey], ed. Arnold, T. (Rolls iSeries), I, 323–5Google Scholar.

13 Bugonis, Electio, Mem. St. Edmund's, II, 29–130Google Scholar.

14 Notices et Extraita, I, 5.

15 “Recherchea sur les écrits de Pierre le Mangeur”, Recherckes de Thealogie ancienne et médiévale [R.T.A.M,], III, 1931, 366–72Google Scholar. Dr Glunz, H. printed, part of this gloss from Pembroke. 7 in the Vulgate in England [from Alcuin to Roger Bacon], Cambridge, 1935, 355–9Google Scholar. under the mistaken impression that it was by Gnnaetete. He had not seen, the notices, by Hauteau and Landgiaf.

16 Cf. Martin, R., Pierre le Mangeur: Be Sacramentis (Spicilegium Sacrum Lovan-iense), 1937, XXVIIIGoogle Scholar.

17 fo 144: Unde cum queritur a peregrinis nostris laids nomen, imperatoris Con-staiitinopolitani dictint quod, vocatur Mamie[1].

18 See note at end of article.

19 Described by Lacombe, G., Studiet, 31–9Google Scholar.

20 fo 23. Cantnrium dicitur in Sentenliis, ubi ostenditur quod plus peccavit Eva quam Adam. Ibi eniim dicitnr quod Eva in, se et in Dominum et in proximiim peccavit. Cf. Sent, II, XXI c. 5.

21 On, the distinctio see Hunt, R. W., “English Learning in the late Twelfth Century”, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, XIX, 1936, 33–4Google Scholar; Moore, P. S., The Works of Peter of Poitiers, Washington U.S.A., 1936, 78 seqGoogle Scholar.

22 The next three paragraphs are a summary of my articles: “Gilbertus Univenalis [Bishop of London (118–8–34), and the Problem of the Glossa Ordmariay]”, “La Glossa Ordinaria [:quelques prédécesseuis d'Anselme de Laon]”, M.T.A.M., 1935-1937, VII 235–62Google Scholar; viii, 24–60; IX, 365–400, where the references will be found. I refer to the whole work as “the Gba”, to its parts as “glosses1”.

23 , Migne, P[atrologia] L[atma], CXIII, CXIVGoogle Scholar.

24 Peter Comestor, fo 254d: Vide quia glosator hoc apposuit, nee eat de litteia leionimi. Littera enim Ieionimi expeditior est: et aptius oantinuatur.

He refers to the: Fseudo-Jerome on St Mark.

25 On Jeremias, fo 188B: Modo lege interlineares. Volo enim notare omnes quas debts, hie legeane, quia in quibusdam sunt multe que appunetaii.de sunt in hoc loco.

26 Ghellinck, J. de, art. “Pierre Lombard”, Bictiounedre de Thélogie CatholiqueGoogle Scholar.

27 Printed by Dr , Glunz, The Vulgate in England, 341–50Google Scholar. Herbert's edition is much more reliable than the printed one in P.L. CXCI.

28 But Herbert tells us that the Lombard did not intend his work to be read in the schools (cf. p. 343). Therefore he does not dispose of the Comestor's claim, to begin the glossing of the Gloss as an academic exercise.

29 The Vulgate in England, chap, v, 197–259.

30 fo 4b on Ps. iv, 6: hoc secundum opinionem magistri Anselmi qui putavit partitionem ease ubicumque esset diapsahna. He is contrasting Anselm's use of the diapsabna with Peter Lombard's. The Cambridge University Library MS. Dd IV, as, fo 4v, an early copy of the Gloss, ascribed to, Anselm, shows the division at Ps, iv, 6.

31 i. The Gloss, MS. Dd IV 25, fo 31: Persona regnantis.

ii. The Great Gloss in the edition of Herbert of Bosham, MS Trinity College Cambridge B. 5.4, fo 12v: et nota qum persona regnantis hie loquitur i. e. Christus utregnans, vel persona regnantis i.e., Patris, piomisit hec.

iii. The Pembroke gloss, fo 3a-b; Persona regnantis Are loquitur. In antiqua glosatura erat hec glosa interlinearis et potest sedere super hanc dictionem me vel super hanc dictianem Dominus. Si super me sic expanes: persona regnanth, i. e. Christie regnans, si super Dominus sic: persona regnantis, i.e. Patris etc.

Stephen Langton has a, very similar note in his gloss on the Great Gloss on St Paul: in glosafura Amseltui coherenletn est interlinearis. Cf. Lacombe, G., Studies, 59Google Scholar.

32 Cf. “La Glossa Otdinaria”, R.T.A.M. IX, 385 n. 2.

33 Cf. “Gilbertus Universalis”, R.T.A.M. VII, 255.

34 fo 228dThe Vulgate in England, 206.

35 Quoted by Landgraf, A., “Familienbildung bei Paulinenkammeiitaren des 12 Jahihunderts”, Bibtka, XIII, 1933, 67Google Scholar.

36 “La, Glossa, Ordinaria”, R.T.A.M. IX, 400.

37 Robert of Melun protested strongly against this method. Cf. Bliemetzrieder, F., “Robert: von Melun und die Scliule Angelina von Laan”, Zeibckrift fiir Kircken-gesdrichte, LIII, 1934, 115–170Google Scholar.

38 fo 260: Sed attende diligenter modum et Ofdinem ittstitytionis…Hoc etiam quod in aliis Evangeliis invetiitur scil etcdpile et comedite ineulcitio est et i.e. comedite, et hoc ideo ut notetur quod alii debent dispensare et: aliis ministrare quatn qui conficiunt, Meet etiam ex. iusau ipsorum euros dispensent; sed hoc ipsi sacerdotes dicuntur facere. Unde delata eat mala consuetudo quod, sacerdotea consuebant in quodam monasterio dire viris, et [ut] ipsi post datent uxoribus. The Thesamna Linguae Latimae IV, 1581, gives “chalice”. for cyathus or ciatus.

39 fo 225:…ut qui dicit: in tali oonstellatione natus sum, non possum ab huiusmodi peccato abstinere.

40 fo 193bb-c The context is interesting: Chaldea enim lingua et Hebrea in apice differunt, sicut Lumbatdia et Fiandgena…: Nota Chaldei scripturam habent Hebiaicam, aed verborum proJationes valde divenas, sicut Hyberni et Scot! nostma litteras et acriptuns habent, sed. divenas littentnim proktiones. Unde nos vix possumus eos, legentes intelligere. I have corrected this passage from MS. Lat. 14417, fo 210b, as the text is better.

41 fo 195d: quoted in La Glosia Ordinaria, 395.

42 La Glossa Orditmria, 389–97.

43 Cf. Smalley, B., “Andrew of St Victor Abbot of Wigmoie, a TWelfth-Centuiy Hebraist”, R.T.A.M. Oct. 1938Google Scholar.

44 PX. CXCVI, 601–66.

45 fo 144e: lodei nostri temporis Ptnrvipontini stint, et tamquam de sophisimitr compositionis, instructi per [pre]dicationemi accipiendum esse inquiunt, non per campositianem, quod dictum est virgo concipet, i.e. ilia qtie est virgo non manens vitgo.

46 Cf. “Gilfaertus Univenalis”, R.T.A.M. VIII, 5:1,–60.

47 I am very much obliged to Mr J. Dickinson for pointing out: this notice to me.

48 Cf. “The Lombard's Commentary on Isaias”, 127–8; I used the Chanter's gloss in MS. MAI. Nat. Lat. 17988, fo 109a, for collation.

49 The MSS. 25a of the Royal Library Brussels, and Mazarine 133 contain the same text of the Chanter's gloss on Isaias. There may be others which resemble the: gloss in MS. Pembroke 7 more closely. No critical study of the Chanter's exegesis has yet been made.

50 See above n. 18.

51 Gottlieb, T., Mittelalterliche Bibliothekshataloge Ötterrada, 1, Vienna. 1915, 301Google Scholar.

52 Early thirteenth-century, of unknown, provenance. It is fully described by Laoombe, G., Studies, 37–9Google Scholar.

53 Studies, 138.

54 The Authenticity of tyhe “Summa”, 103.