The Iron Age of southern Africa has been of archaeological interest for over 150 years because of Great Zimbabwe and related stone-walled palaces. Overall, these palaces cover an area the size of France. Many of them became known to the Western world in the nineteenth century through the search for ‘ancient gold workings’ (e.g. Hall & Neal Reference Hall and Neal1902). As a result, Zimbabwe is well known for stone-walled palaces, but few researchers realize that Botswana also hosts more than a hundred. Some have been documented before (e.g. Huffman & Hanisch Reference Huffman and Hanisch1987; Mothulatshipi & Thabeng Reference Mothulatshipi and Thabeng2018; Tsheboeng Reference Tsheboeng1998; van Waarden Reference van Waarden2012; Walker Reference Walkern.d.), but many, we believe, have been misinterpreted. Our present study therefore serves as a re-assessment.

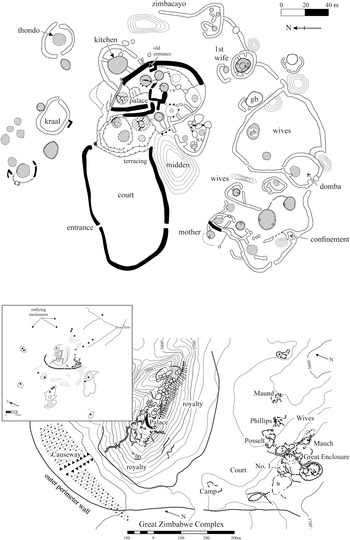

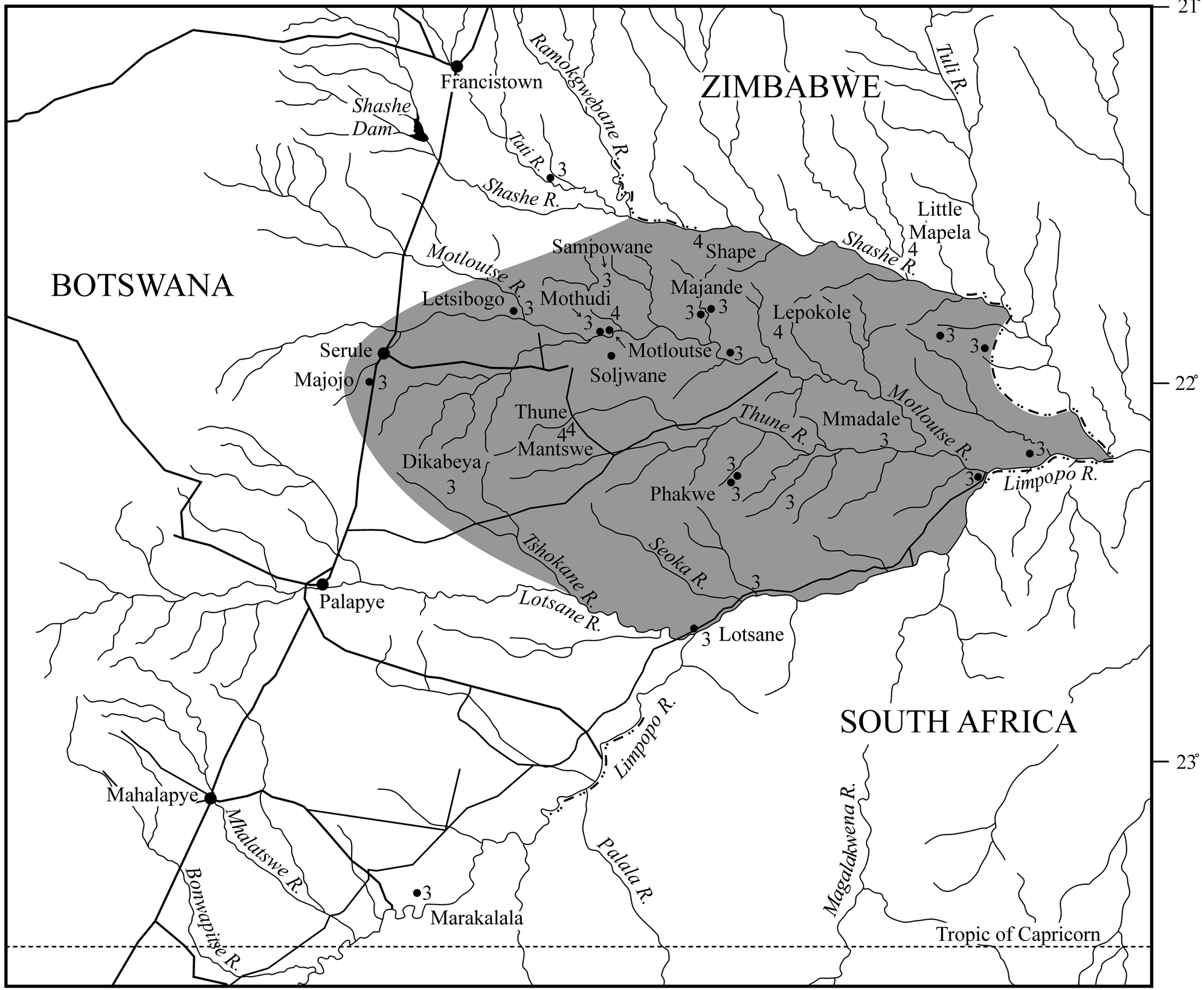

The Zimbabwe Culture (or Zimbabwe Tradition) has three overlapping periods: Mapungubwe (ad 1200–1320); Zimbabwe (ad 1300–1700); and Khami (ad 1400–1840). Each period is named after the most prominent capital (each is on the World Heritage list), but each period could encompass more than one state. The Mutapa state, for instance, belongs to the Zimbabwe period along with Great Zimbabwe, while the Rozvi and Torwa states belong to the Khami period (Huffman Reference Huffman2007). We focus on the Khami period in the greater Tuli area of Botswana, although our approach is applicable to the wider region (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Research area and other important sites in southern Africa.

Our approach is part of Cognitive Archaeology, the study of a past society's worldview. By worldview we mean an aggregate of symbols that give meaning and expression to social organization, a series of rules to govern behaviour and a set of values to guide choice. Such a worldview constitutes a system of beliefs about people, society and the natural world that is passed down successive generations. We access this worldview through the social organization of settlement space, based on the principle that human groups everywhere divide their spatial environment into discrete categories where only a limited range of culturally related activities are permitted (e.g. Rapoport Reference Rapoport1969). We access settlement organizations in turn through the ethnography of descendant communities. This ethnography is critical. If researchers do not incorporate appropriate indigenous knowledge, they impose their own worldview—a pervasive problem throughout archaeology.

For the Zimbabwe Culture, we use sixteenth-century Portuguese eye-witness accounts, Shona oral traditions and Venda ethnography. Ancestral Venda spoke Kalanga (and were therefore Western Shona) before they incorporated Sotho-Tswana to create the present Venda language (Lestrade Reference Lestrade1927; Loubser Reference Loubser1991; Wentzel Reference Wentzel1983). Venda provide important models because they were not as affected by sixteenth-century Portuguese interference, the early nineteenth-century difaqane/mfecane nor late nineteenth-century British colonialism as were Shona in Zimbabwe. These sources were used to derive the Zimbabwe Pattern, which was then applied to some 70 Zimbabwe Culture settlements (Huffman Reference Huffman1982; Reference Huffman, Wendorf and Close1986b; Reference Huffman1996). This pattern, its application and overarching paradigm have their critics (e.g. Beach Reference Beach1998; Chirikure & Pikirayi Reference Chirikure and Pikirayi2008; Chirikure et al. Reference Chirikure, Manyanga, Pollard, Bandama, Mahachi and Pikirayi2014; Pikirayi & Chirikure Reference Pikirayi and Chirikure2011) but no one has presented a comprehensive alternative that explains the archaeological data better (see Huffman Reference Huffman2010; Reference Huffman2011; Reference Huffman2015, for detailed replies). We apply that pattern here as a model to explain the Botswana sites.

Cultural landscape

Anthropologically, the Zimbabwe Culture is characterized by institutionalized class distinction linked to the ideology of sacred leadership (Huffman Reference Huffman1982; Reference Huffman1996). In pre-colonial times, this culture encompassed only Shona and Venda speakers, continuing into the twentieth century among Venda. According to the ethnography, a mystical association linked the leader, the land and God. To Zimbabwe people, God made it rain, and it is to God one must turn through the spirits of dead leaders. Sacred leaders were therefore the rainmakers, interceding through royal ancestors to God on behalf of the nation for rain and other blessings. For ritual protection, sacred leaders ruled from stone-walled palaces—known as dzimbahwe in the Shona language. Today, dzimbahwe means ‘houses of stone’, but in the sixteenth century it meant ‘the home, court, and grave of a leader’ (De Barros 1551, in Theal Reference Theal1898–1903, VI, 267). We use the original meaning here. Many dzimbahwe were built on hilltops because of a metaphorical association between the majesty of mountains and kingship. ‘To climb the mountain’, for instance, means to approach the leader (Hamutyinei & Plangger Reference Hamutyinei and Plangger1987, Proverb 1486), while ‘the mountain has fallen’ refers to his death. Moreover, some dzimbahwe had extended covered passageways so that when a person entered the palace, they also entered the ‘mountain’. Sacred leaders were also linked metaphorically to crocodiles: both were dangerous, ferocious and feared no enemies, and both were associated with rain (Hemans Reference Hemans1913; Stayt Reference Stayt1931, 204; van Warmelo Reference van Warmelo1971).

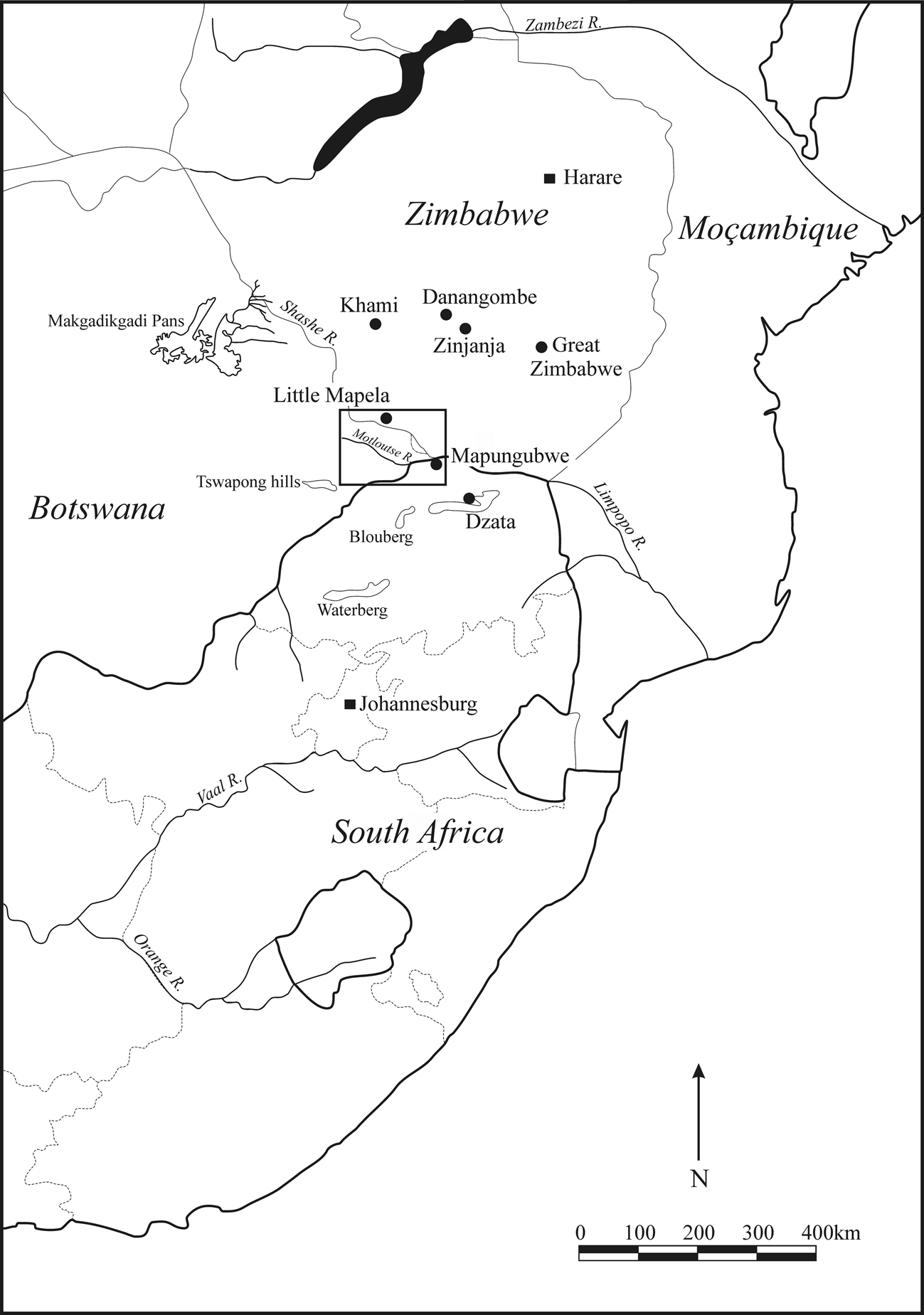

According to Portuguese accounts and other ethnographic data (for details, see Huffman Reference Huffman1986a,Reference Huffman, Wendorf and Closeb; Reference Huffman1996), palaces were the political headquarters of chiefs and kings of various importance. Throughout southern Africa, political levels in Bantu-speaking societies were based on a hierarchy of courts. In this hierarchy, a homestead head (Level 1) judged disputes between members of his settlement, but if a dispute arose between two homesteads, the neighbourhood headman (Level 2) was the adjudicator. If the dispute could not be resolved, or if it involved people from two different neighbourhoods, the case was taken to the local petty chief (Level 3). People in two different chiefdoms took their cases to the senior chief (Level 4) and then to the paramount (Level 5). Thus, each chiefly level was the apex of a pyramid of lower courts.

The sizes of territories and capitals correlated with population numbers because of a systematic relationship between political power, the unequal distribution of wealth and the number of wives and followers: as the saying goes, ‘big men live in big settlements’. Significantly, this relationship was not ethnically specific, but applied to pre-colonial societies throughout southern Africa (Huffman Reference Huffman1986a,Reference Huffman, Wendorf and Closeb). Generally, each level had two to three times more people than the level below. Thus, Level 6 capitals housed some 12,000 to 18,000 people (note half would have been children); Level 5 capitals contained some 5000 people, while Level 4 capitals had 1500 and Level 3 capitals some 300. Both Levels 2 and 1 homesteads had about 50 to 100 people each. In historic times, Tlokwa in Botswana had a Level 3 polity (Ellenberger Reference Ellenberger1939), while the Ngwaketse (Schapera Reference Schapera1942) reached Level 4 (Table 1). In terms of territory, a petty chief typically controlled about 3000 sq. km, a senior chief about 10,000 sq. km and a paramount about 30,000 sq. km (the size of Swaziland). The Mutapa state had five levels at its peak, but Great Zimbabwe and Khami were both state capitals of Level 6 hierarchies and probably controlled a minimum of 90,000 sq. km. Traditionally, any leader at the top of a substantial hierarchy, such as Levels 5 and 6, could be called mambo [king]. According to documentary evidence (see Beach Reference Beach1980), rebellions were common, and the size of any mambo's polity varied in response to political dynamics.

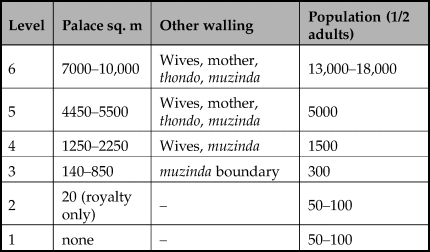

Table 1. Political pyramid for chiefdoms and states in southern Africa.

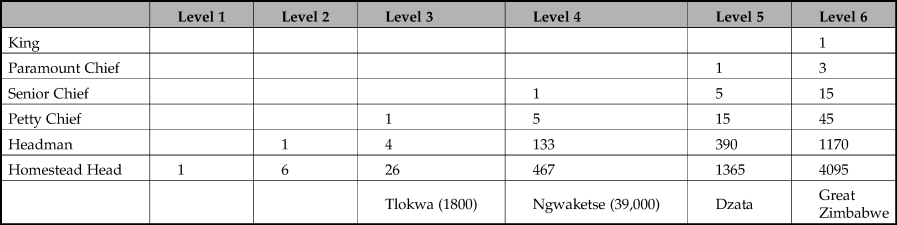

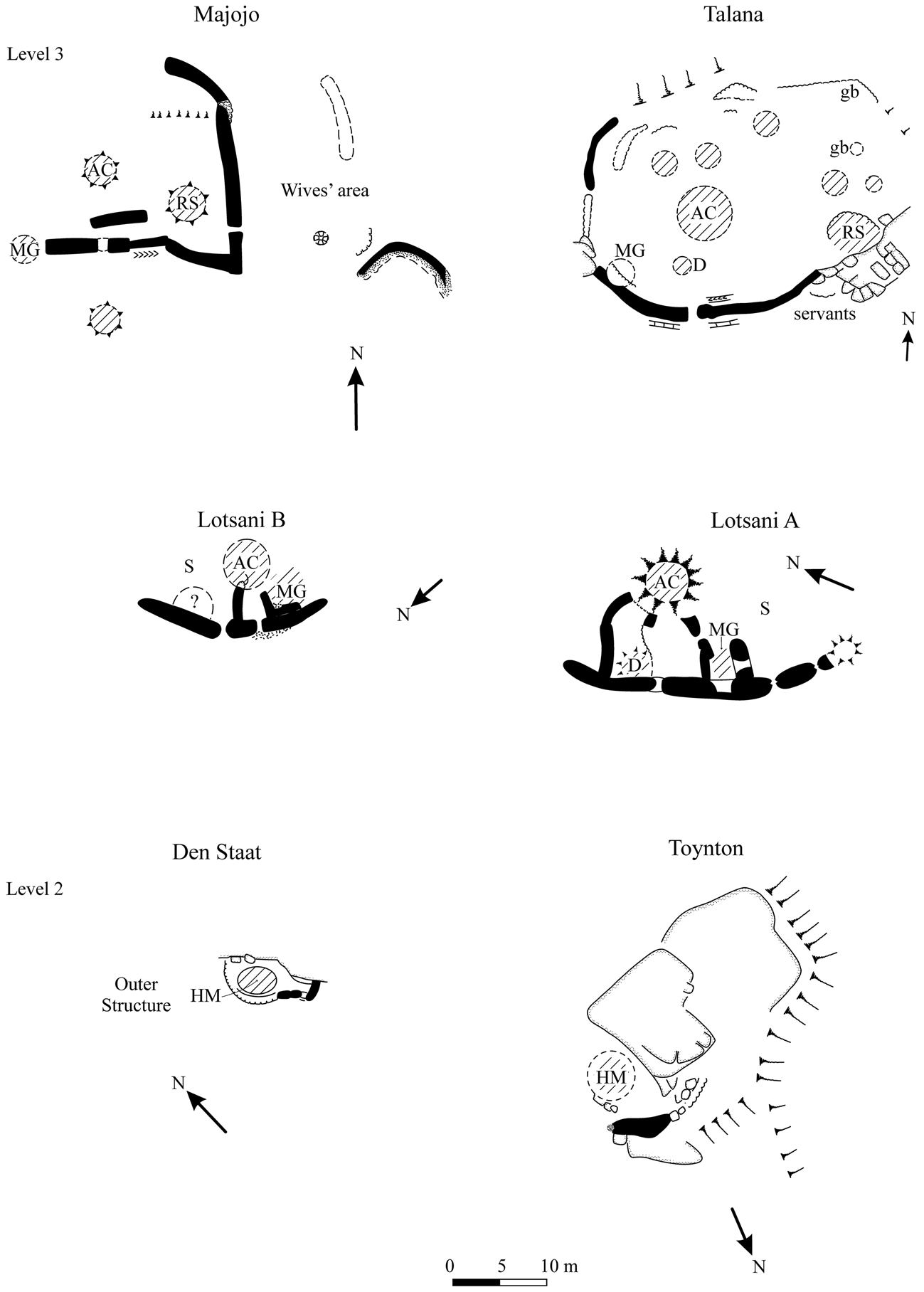

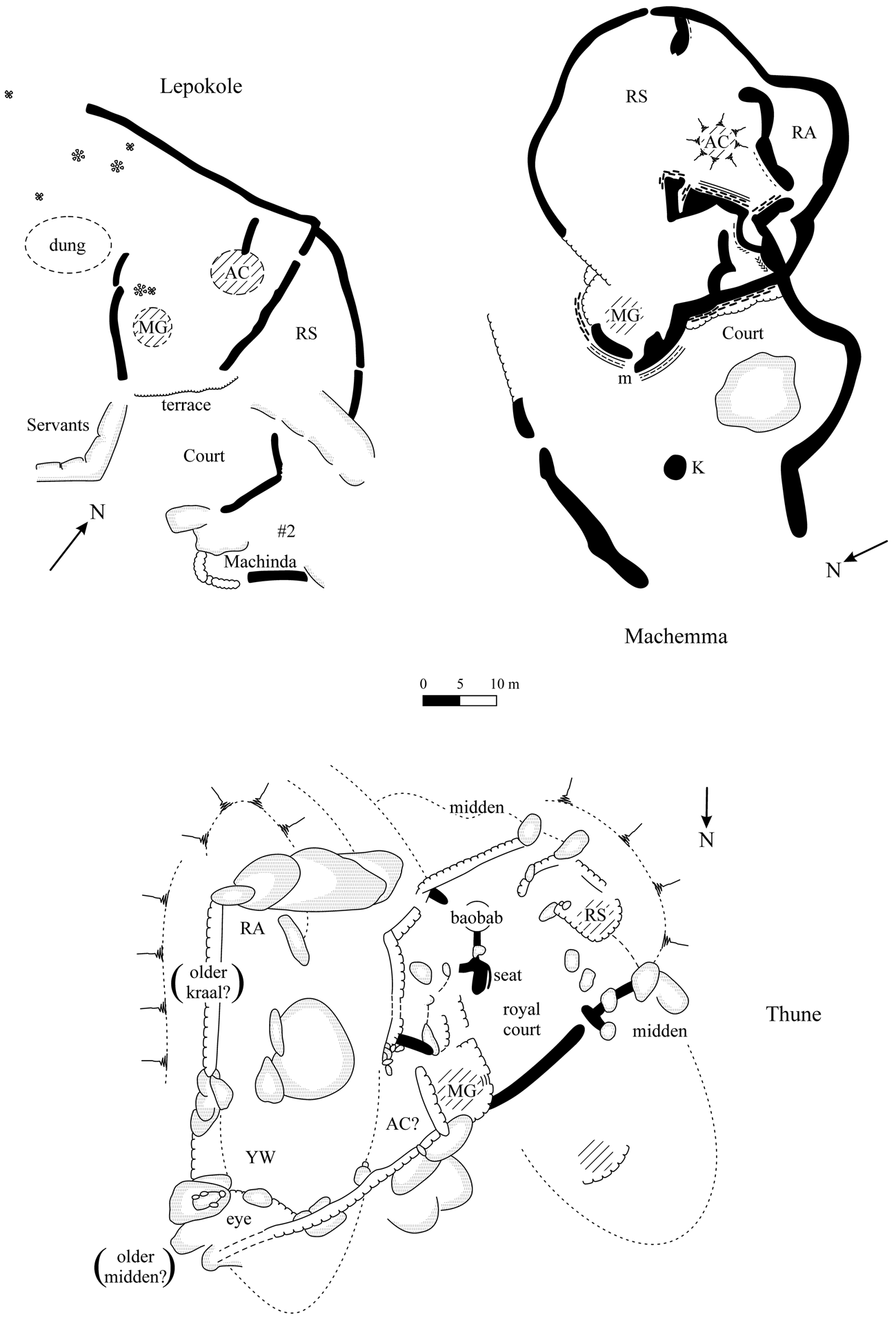

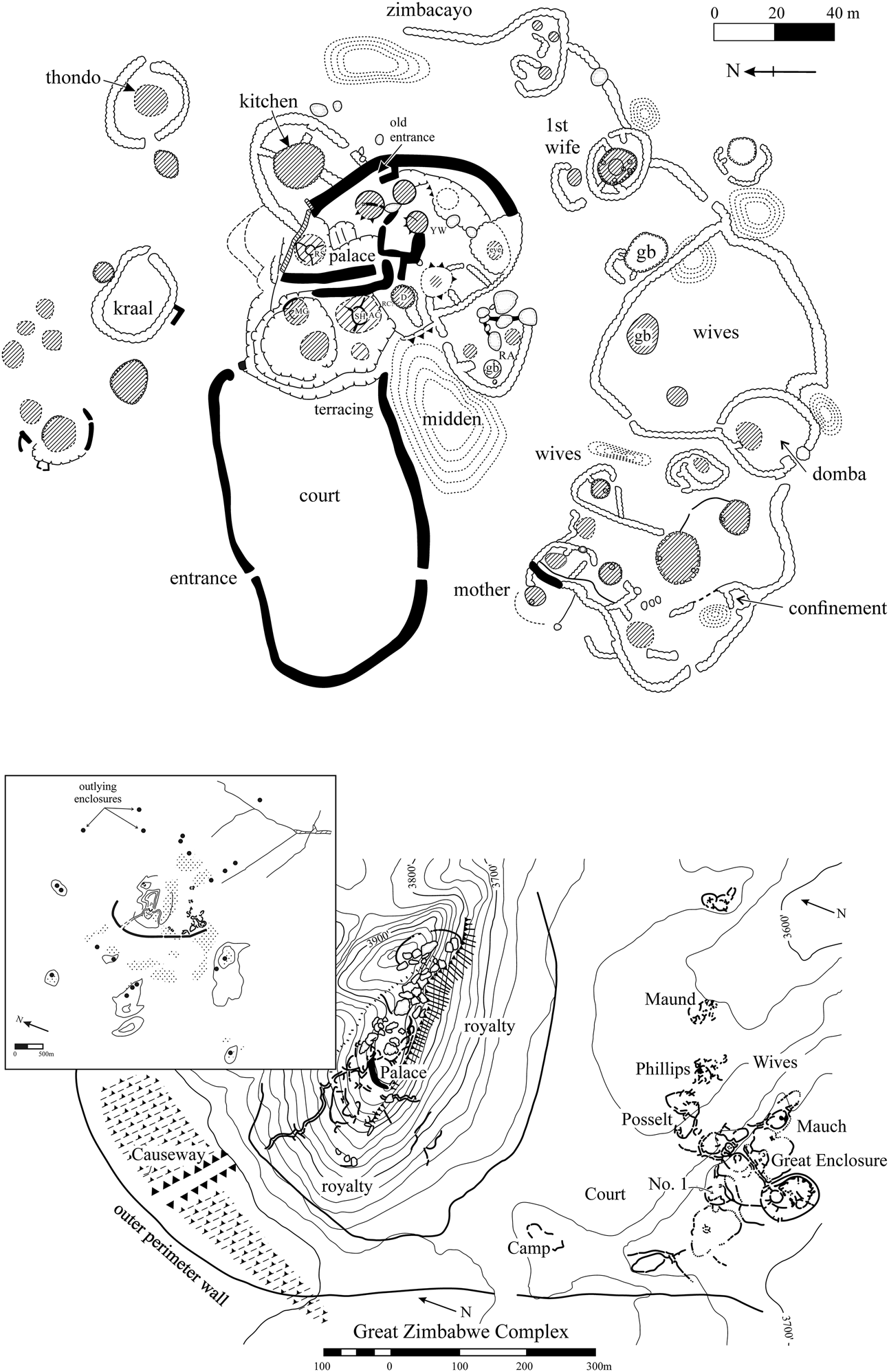

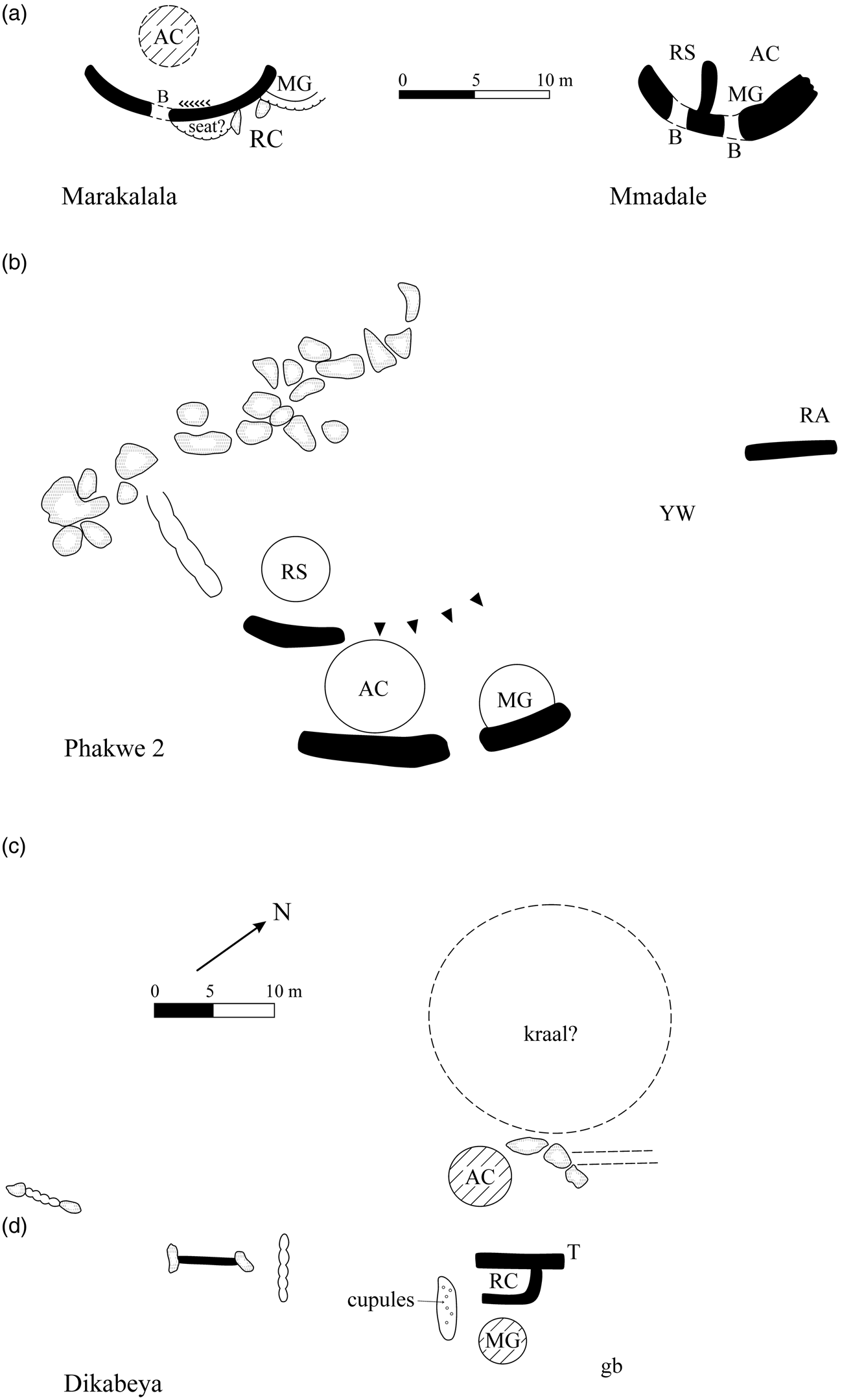

This hierarchy was well established in the past, but present methods to calculate levels of political importance are contentious. Other than eyewitness counts, the most important factor for determining residential populations is settlement size. When these data are not available, it is possible to use palace size in conjunction with other walling to determine populations. This procedure is applicable, we know, because a long-term drought in the Limpopo Valley in the 1980s had removed surface vegetation, revealing whole settlements and the variability in stone walling (Huffman & Hanisch Reference Huffman and Hanisch1987). In summary, commoner settlements (Level 1 and most Level 2) lacked prestige walling altogether. Most headmen (Level 2) were commoners, but headmen of royal blood sometimes had a short length of walling next to their house. The palaces of petty chiefs (Level 3) begin the sequence of sacred leadership, varying from 10 to 30 m across, providing space for the audience chamber, messenger, doctor, leader and ritual sister at the front. Besides a larger palace, the wives’ compound of Level 4 (senior chief) leaders was often enclosed in stone walls (Figs 2 & 3). The headquarters of paramount chiefs, or mambo at Level 5, are rare: they incorporated large palaces, large wives’ compound and the residences of other dignitaries, such as the royal mother, brother in charge of the court and the youngest regiment: Danangombe (also Danamombe and Dhlo Dhlo) is the best-known example (Caton-Thompson Reference Caton-Thompson1931; MacIver Reference MacIver1906). The headquarters of Level 6 mambos are even rarer: Great Zimbabwe (Caton-Thompson Reference Caton-Thompson1931; Summers et al. Reference Summers, Robinson and Whitty1961) and Khami (Robinson Reference Robinson1959) are the only ones on record (Fig. 4, Table 2).

Figure 2. Stone-walling associated with royal headmen (Level 2) and petty chiefs (Level 3). (Adapted from Huffman & Hanisch Reference Huffman and Hanisch1987 and Huffman Reference Huffman1996.)

Figure 3. Stone-walling associated with senior chiefs (Level 4) at Lepokole, Machemma and Thune. (Adapted from Huffman & Hanisch Reference Huffman and Hanisch1987 and van Waarden Reference van Waarden2012.)

Figure 4. Town plans: Danangombe (L 5) (above); Great Zimbabwe (L 6) (below). (From Huffman Reference Huffman1996.)

Table 2. Political levels and settlement size.

A few caveats should be noted. Despite the level, rough walling at most dzimbahwe demarcated the muzinda boundary (musanda in Venda), the chief's area surrounding the palace. Furthermore, only the first headquarters of a chief should have a stone-walled initiation centre in the wives’ area (the domba in Venda): later headquarters of the same leader did not host these initiations because the chief had transferred the duty to subordinate headmen (Blacking Reference Blacking1969, 149; Victor Ralushai pers. comm., 1983). To determine levels, it is therefore important to distinguish between initiation centres and the compound for royal wives, as well as between a muzinda boundary and the palace. In addition, the distance between the palace and initiation centre is also relevant. At Matendere (Caton-Thompson Reference Caton-Thompson1931), for example, the initiation complex, associated with the wives’ area, is some 210 m away from the large palace (Huffman Reference Huffman1996, 171–2).

Historically, Shona and Venda people used rivers and other natural features to designate political boundaries between capitals (e.g. Holleman Reference Holleman1952, 11). As a result, capitals were not equally spaced across the landscape, following something like a Central Place Theory (contra Garlake Reference Garlake1978 and van Waarden Reference van Waarden2012). Instead, many dzimbahwe were sited near rivers because it was necessary to defend boundaries, not the middle of the territory (see Huffman & du Piesanie Reference Huffman and du Piesanie2011 for Limpopo examples). The distribution of sites at Letsibogo provides an example of Level 2 royal headmen as well as a Level 3 chief and their followers in the Motloutse Valley (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Kinahan and van Waarden1996; Huffman & Kinahan Reference Huffman and Kinahan2002/3). Level 4 capitals, on the other hand, were sometimes placed in the middle.

In the absence of radiocarbon results, researchers have tried to date these settlements by walling styles based on Whitty's (Reference Whitty1961) now classic scheme. At Great Zimbabwe, Whitty devised the P-P/Q-Q-R sequence based on abutments in the Great Enclosure. P-Type walls (no foundations, no batter, square doorways and uneven coursing) were the earliest, followed by Q-Type (prepared foundations, a marked batter, rounded doorways and regular coursing). Note that P-Type walls had uneven coursing because the builders collected stones from the surface before they began to quarry blocks of similar size. Other than R (rough coursing contemporary with the others), his scheme applied to the entire town. Its application outside Great Zimbabwe, on the other hand, is not straightforward. For one thing, only granite typically exfoliates in regular blocks, so level courses were not easy to achieve with other stone, especially if they were collected from the surface. For another, different walling types could be intentionally used to designate gender and other statuses (e.g. Zinjanja in Huffman Reference Huffman1996, 72). And then there is the expertise of the builders. Had the king at Great Zimbabwe (or Khami) sent skilled craftsmen to build dzimbahwe throughout his kingdom, numerous palaces would be more similar in shape, size and quality. It is therefore inappropriate to apply rigidly an architectural scheme developed for a large urban centre where specialist builders used granite—much of it quarried to produce even-sized blocks—to small centres with a different geology far away from the main capital. For these reasons, Summers (Reference Summers1971, 74) found it difficult to distinguish between P- and Q-coursing outside Great Zimbabwe. Shenjere-Nyabezi et al. (Reference Shenjere-Nyabezi, Pwiti, Sagiya, Chirikure, Ndoro, Kapumha and Makuvaza2020) reached a similar conclusion for the Hwange District. Moreover, Khami period palaces had the Platform-Type (retaining walls with Q-coursing and square doorways) that was not in Whitty's scheme. As a result, identifications need to be based on principles of construction and purpose, following Whitty (Reference Whitty1961), rather than the visual appearance of the veneer. We use Whitty's principles in our re-assessment.

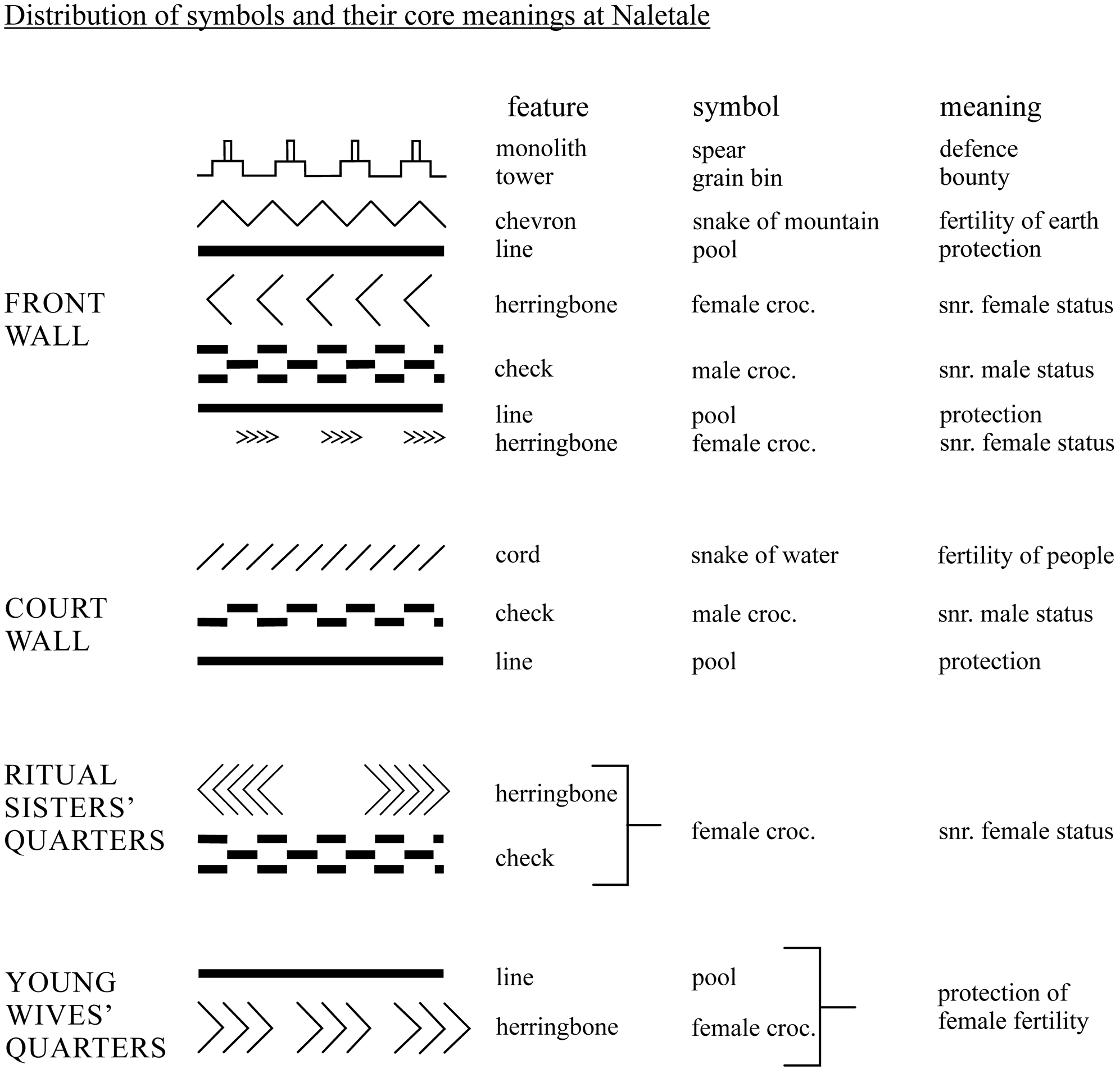

Researchers have also used wall decoration to date different palaces (e.g. Summers Reference Summers1959). Dentelle, for example, is associated with Zimbabwe period walls, while check designs only grace Khami period palaces. Otherwise, decorations on different walls denote social roles in conjunction with function (Huffman Reference Huffman1996, 113–15). Thus, designs on the front wall refer to sacred leadership (dentelle & check = male crocodiles, while chevron & cord = snakes and fertility); those on the side, to the residence of the ritual sister (herringbone = female crocodile); and those at the back, to fertility (dark stones = pool) (Fig. 5). Pool designs can also mark the court and leader's private area, as well as the front, in reference to the aloofness of a sacred leader: as Venda say, ‘the crocodile does not leave its pool’. The court walls at Naletale and Danangombe, furthermore, are decorated with check, cord and dark bands, expressing a common symbolic triad in Venda iconography: ‘the crocodile in its pool guarded by a giant snake’ (Nettleton Reference Nettleton1984). The profuse decoration at late palaces, such as Zinjanja (also Regina: White Reference White1903–4), Naletale (MacIver Reference MacIver1906) and Danangombe (Caton-Thompson Reference Caton-Thompson1931) may have social as well as chronological implications (van Waarden Reference van Waarden2012). We return to this point at the end.

Figure 5. Wall decoration at Naletale. (From Huffman Reference Huffman1996.)

We turn now to the physical setting.

Physical landscape

East-central Botswana has a complex geology. It contains portions of both the Kaapvaal and Zimbabwe cratons, separated by the Limpopo Mobile Belt, a sandstone landscape punctuated by igneous intrusions. For the greater Tuli area, the Shashe River forms the eastern boundary, the Limpopo the southern boundary and the Mhalatswe more-or-less the western boundary. The Motloutse and its tributaries flow through the middle (Fig. 6), through a rainfall trough defined by the 350 mm per annum isohyet surrounded by a 400 mm arc (Jackson Reference Jackson1961, pl. 2). The Motloutse, however, starts further north where rainfall is higher, so that it may well flow, and even flood, during drier seasons further south. As a result, the Motloutse floodplains are and were an important source of cultivable land. Significant for our purposes, the rainfall trough extends to the nearby Limpopo Valley where the pre-colonial rainfall pattern is well known through isotopic studies of animal bone (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Lee-Thorp and Hall2007) and baobab rings (Woodborne et al. Reference Woodborne, Hall, Robertson, Patrut, Rouault, Loader and Hofmeyr2015). The Motloutse trough indicates that rainfall data for the Limpopo Valley (Huffman & Woodborne Reference Huffman and Woodborne2016) are relevant, even though the two areas may not have been precisely the same.

Figure 6. Greater Tuli area of east central Botswana.

Previous records

Zimbabwe Culture palaces in Botswana have been on record since the first European explorers. One Lotsane palace, in fact, is the first to have been accurately mapped (Hall & Neal Reference Hall and Neal1902, 329). Using these data plus others on file with the Historical Monuments Commission of Rhodesia, Roger Summers (Reference Summers1953; Reference Summers1959) plotted the distribution of palaces throughout southern Africa with an emphasis on wall decoration. Later, Peter Garlake (Reference Garlake1970) classified walling types from an architectural perspective, extending Whitty's study to the Khami area and to Platform-Type constructions. Indeed, Khami platforms versus Zimbabwe free-standing walls is a distinction still recognized today (e.g. Pikirayi Reference Pikirayi2013; van Waarden Reference van Waarden2012).

Van Waarden (Reference van Waarden2012, table 8.3 and appendix B) provides the most comprehensive assessment of stonewalled palaces in Botswana. Her classification of political levels, however, differs from ours in that she emphasizes the volume of stonework as a proxy for power, rather than the volume of enclosed space as a proxy for settlement size. Nevertheless, our separate classifications are remarkably similar.

We begin our assessment with the smallest sites. Our assignments of spatial function are based on the ±50 palaces presented in Snakes & Crocodiles (Huffman Reference Huffman1996), a few more in South Africa (Huffman & du Piesanie Reference Huffman and du Piesanie2011) and several field trips to the Tuli area.

Re-assessment

Level 3: Petty chiefs

Most dzimbahwe in the Tuli area were headquarters of small chiefdoms. Palace walling often encloses daga [mud] mounds that mark the audience chamber and sometimes the messenger's office (the official who organized access to the leader), the doctor (the official who could detect a person with evil intentions) and residence of the ritual sister (senior female of the ruling line). Furthermore, house circles and granary bases often designate the residences of followers.

Marakalala (Marakalelo), located about 4 km north of the Limpopo, is the furthest south of any known dzimbahwe. There, a well-built arc of stone walling, some 10.5 m across, marks the palace (Fig. 7a). Inside, a herringbone design (female crocodile) on the south section stands opposite a dark band (pool) to the north: both sections meet at a blocked doorway. Another small palace, Mmadale, overlooks the Thune River a few kilometres upstream from its confluence with the Motloutse. The front arc here is about the same size as Marakalala, but more dilapidated: it too contains blocked doorways (Fig. 7b). The next two palaces were probably shifting capitals of the same chiefdom. Phakwe 1 (28-A4-3) is located on the western end of a small hill, while Phakwe 2 (28-A4-2) stands to the east: both are on the south side about 17 km upstream of the confluence of the Phakwe River with the Thune. Both have arc-shaped walling like Lotsane, Marakalala and Mmadale. At Phakwe 2 (Fig. 7c) the remnants of a large retaining wall at the back of the hill probably marks a ritual area and private residence of a young wife. Another small palace located in the Dikalate hills east of Majweng, Dikabeya (Botswana Site 27-A2-6), was thought to be a Level 4 palace, but only a short palace wall (about 7 m long) stands behind a small private court (Fig. 7d). Dikabeya thus belongs to Level 3: it may well sit on top of older deposits, making it appear more substantial.

Figure 7. Level 3 palaces: (a) Marakalala; (b) Mmadale; (c) Phakwe 2; (d) Dikabeya.

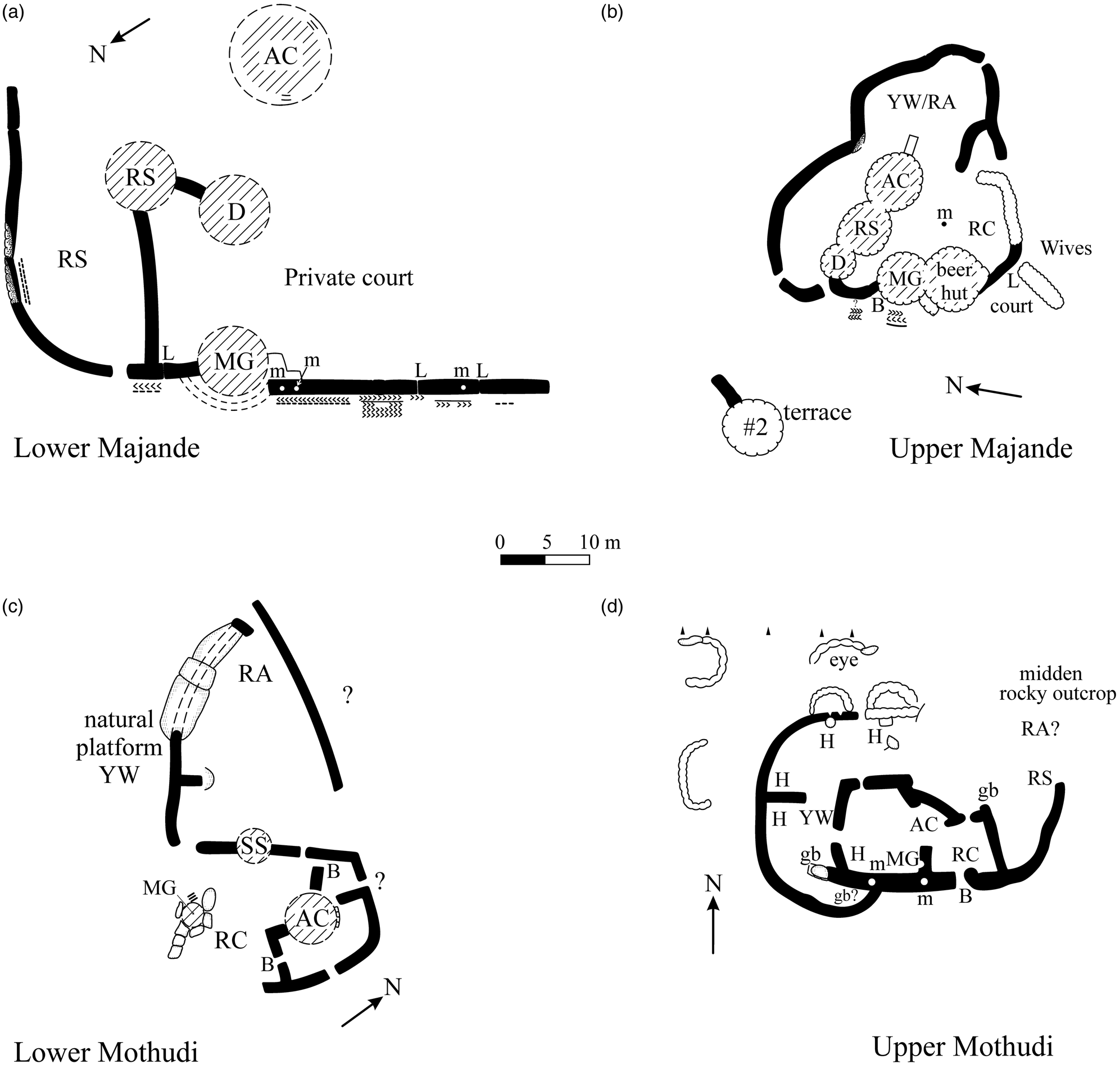

Researchers have also mistakenly classified another two palaces as a single Level 4 complex. Located on either side of the Sekgopye River, Upper and Lower Majande stand about 7.5 km upstream of the Motloutse. The two walled areas, according to Tsheboeng's (Reference Tsheboeng1998) thesis and Botswana Museum signage, formed one site with Lower Majande occupied by royal wives and Upper Majande by the leader. This interpretation follows the pattern at Great Zimbabwe, except the enclosures there are not separated by a river. This geographic point means the two Majande buildings were palaces of separate chiefdoms. This is a new interpretation, but entirely consistent with Shona and Venda practice.

In further support for this re-interpretation, the two buildings have the same basic organization (Fig. 8a & b). Both have a smaller compartment for the ritual sister, monoliths to mark the larger chief's side, raised platforms for the messenger and doctor, audience chambers (with two entrances at Lower Majande), blocked doorways, private royal court inside, while loopholes (i.e. windows) gave visual access to the public court outside. It was here that commoners would have brought gifts and tribute to the leader as thanks for performing his duties. As a sacred leader, it was his responsibility to guarantee prosperity from the earth (through adequate rainfall) and defence of his people (through the courts and military). The profusely decorated front walls proclaimed these duties through crocodile (check & herringbone), snake (cord) and pool (dark band) designs, as well as the stone monoliths (horns of the mambo, i.e. spears).

Figure 8. Level 3 palaces: (a) Lower Majande; (b) Upper Majande; (c) Lower Mothudi; (d) Upper Mothudi. (Majande plans after Walker Reference Walkern.d.)

These organizational and symbolic features, significantly, are not typical of a compound for wives. At Upper Majande, rougher coursing and a doorway further to the right behind the court marked access to and from the royal wives’ area. What is different from Lower Majande is a rough wall with monoliths marking the entrance to the muzinda, a cattle kraal inside and a raised stone platform that may have supported the office of the brother in charge of the public court. Otherwise, the two dzimbahwe are notably similar.

On the hill, excavations (Tsheboeng Reference Tsheboeng1998; Walker Reference Walkern.d.) yielded Letsibogo pottery under the Khami occupation. As a ceramic proxy, Letsibogo marks the entrance of Tswana-speaking people into the greater Tuli area during the Late Iron Age (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Kinahan and van Waarden1996; Huffman Reference Huffman2007, 186–9; Huffman & Kinahan Reference Huffman and Kinahan2002/3). Some may well have been incorporated into the Shona chiefdoms. Despite this possibility, Letsibogo pottery at Upper Majande was more likely the result of earlier rain-control episodes associated with severe droughts, not with the walling. This is another new interpretation. Simply put, Tswana people did not live inside dzimbahwe because they did not practise sacred leadership.

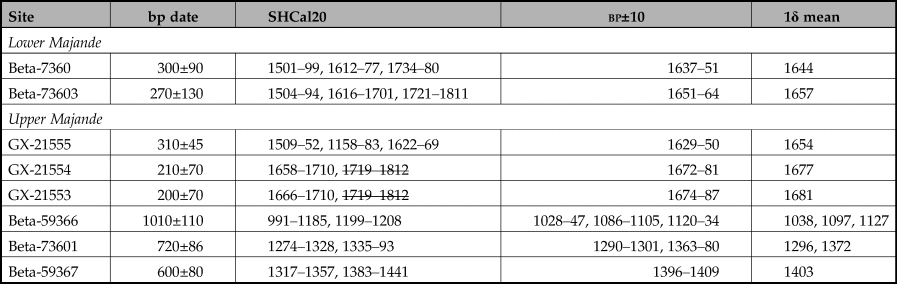

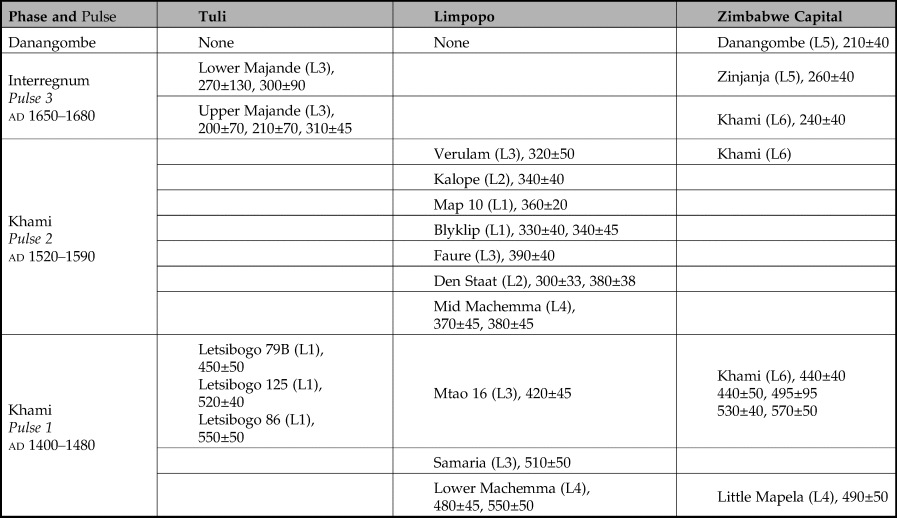

For rain-control activities, three major droughts are on record: one dated ad 1375±25, another to 1465±5 and the third to 1530±10 (Huffman & Woodborne Reference Huffman and Woodborne2016; Woodborne et al. Reference Woodborne, Hall, Robertson, Patrut, Rouault, Loader and Hofmeyr2015); any could have been the reason for Letsibogo rituals. Radiocarbon dates for Upper Majande (Table 3) indicate that the late fourteenth- and mid fifteenth-century droughts were more likely. Other earlier dates recovered from the excavations probably refer to older droughts. Typically, rain-control hills have compressed stratigraphy; and so, artefact associations are often ambiguous.

Table 3. Radiocarbon dates for Upper and Lower Majande.

Table 3 with the dating results requires further comment. First, we calibrated the bp dates using Calib 8.10 (http://calib.org/calib/calib.html) and the southern hemisphere dataset (SHCal20) using Stuiver & Reimer (Reference Stuiver, Reimer and Reimer2018) and Hogg et al. (Reference Hogg, Hua and Palmer2020). This calibration programme reports the median age for the radiocarbon date, but this often falls outside of the 1-sigma intercepts, which is not sufficiently precise when considering Iron Age chronology. Furthermore, the large standard errors yield multiple possible spans (Table 3, column 3). To help choose between different calibrated spans, we calculated the 1-sigma ranges of the midpoint ±10 (column 4) and then the mean (column 5). Note that this is a heuristic device to help narrow the possibilities. With this procedure, Lower Majande most likely dates to between ad 1644 and 1657, while Upper Majande dates to between ad 1654 and 1681; in other words, they were probably contemporaneous.

Another dzimbahwe with highly decorated walling is known as Sampowane (17-D2-5), located about 31 km northwest of Lower Majande. It too comprises a complex of platforms and free-standing walls profusely decorated with herringbone, cord and check. If similarity in wall decoration has chronological implications, Sampowane should have been contemporaneous with the two Majande palaces.

Another pair of buildings stand on top of a range of hills parallel to the Motloutse. Over the years, these ruins have been called Mothudi (van Waarden Reference van Waarden, Lane, Reid and Segobye1998; Reference van Waarden2012) and Leshongwane (Mothulatshipi & Thabeng Reference Mothulatshipi and Thabeng2018). To avoid confusion, we refer to the ruins on the southern hill as Lower (southern) Mothudi (17-D4-2) and the ruins to the north as Upper (northern) Mothudi (17-D4-6). Our plans combine data from previous recordings as well as our own.

Lower (southern) Mothudi has a gravel mound marking the audience chamber inside a U-shaped enclosure about 16 m across and 14 m long (Fig. 8c). Disintegrated gravel on a raised platform behind probably marks the ritual sister's house, while a smaller raised platform to the side was probably the messenger's office: the open space in between would then have served as the private, royal court. About 80 m away stands Upper (northern) Mothudi. Two monoliths (van Waarden Reference van Waarden, Lane, Reid and Segobye1998, 128) once stood on the front wall, marking the chief's compartment (Fig. 8d). Although house remains are not as obvious as at Lower Mothudi, the front section probably enclosed the private, royal court with the audience chamber on the left and the ritual sister's area to the right. Young wives probably lived behind, while the ‘eye’ (the palace guard) was probably stationed on the natural terrace at the back, overlooking a path down the hill.

To be one settlement, as museum signage implies, one walled area would have to have been a wives’ area with a quite different spatial organization from those present. Consequently, Upper and Lower Mothudi were more likely shifting headquarters of one small Khami-Period dynasty, occupying the same hills at different times. This is another new result.

Level 4: Senior chief

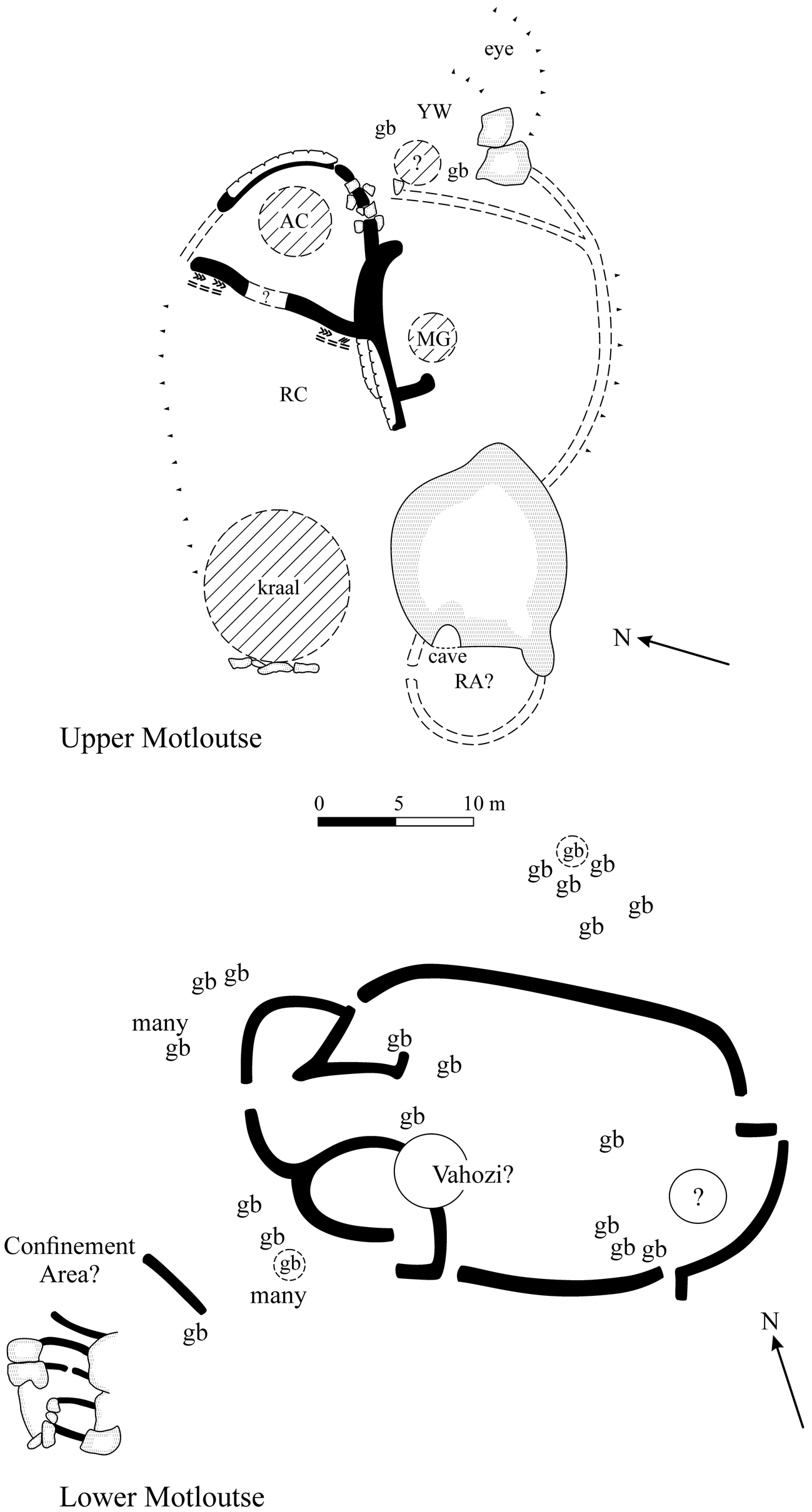

A senior chief's headquarters, known as Motloutse (17-D4-5), stands 4.5 km downstream from the two Mothudi palaces. It also has two walled areas about 80 m apart, but the lower walling was the royal wives’ compound: it contains the remains of several granary bases inside various enclosures (Fig. 9). Presumably, daga houses stood between gaps in the stonewalls, as they did in the Maund enclosure at Great Zimbabwe (Caton-Thompson Reference Caton-Thompson1931). Following the Zimbabwe Pattern, the vahozi's [first wife] enclosure probably stood near two entrances. Most other wives would have lived near the numerous granaries surrounding the main enclosure. A small walled area to the west was somehow connected. Perhaps it was the confinement area for the chief's pregnant daughters who had returned home to give birth (see Gelfand Reference Gelfand1959, 178).

Figure 9. Level 4 Motloutse: (a) Upper; (b) Lower.

Higher up the hill, the palace itself faces west and consists of an arc of retaining wall (messenger) next to an oval enclosure (audience chamber). Cord and check designs appear in two places on the main west wall, while collapsed walling in between may cover a doorway. A few metres to the west, a walled cave may have been the ritual area.

Other Level 4 complexes include Shape and Thune. Shape (18-C2-1) sits on a small hill in rough terrain 7–9 km from the Shashe River. Several terrace platforms, reminiscent of the Torwa state-capital at Khami, cover most slopes (Fig. 10). At the bottom, 15 m to the west, is a free-standing wall that probably designates the front of the wives’ compound: it still bears a broken monolith and blocked doorway.

Figure 10. Shape: (above) hill walling; (below) wives’ area (note blocked doorway).

Thune (27-B2-4), 65 km to the west, was mapped by van Waarden (Reference van Waarden2012, 90). Another palace, now called Mantswe (27-B2-22), stands about 1000 m to the southwest in a different cluster of small hills. This site has not been previously recorded. Here, several terraced platforms surround the summit similar to Shape. At the base 20 m to the west stands a curved wall about 14 m long that, again like Shape, probably marks the front of the wives’ compound. As expected, granary bases stand inside. The two Thune palaces are too close to have been contemporaneous and therefore represent separate occupation periods.

Our final ruin is different and requires a different explanation.

Royal graves

Sojwane is a granite batholith standing about 7 km south of the Motloutse. Today, the hill is a rain-control shrine amid a populous agricultural area. Among other features, local Tswana refer to a quartz dyke as a snake slithering up the hill. This calls to mind the mystical snake—Kgwanyape—who protects the rain-control powers of Modipe Hill from a pool inside a cave (Schapera Reference Schapera1971, 35–42). Following Eastern Bantu cultural logic, Tswana rain makers at Sojwane created a cave among tumbled boulders not far from the quartz snake.

On the hilltop above the snake stands a small dzimbahwe (18-C3-4) consisting of free-standing walls erected between natural boulders (Fig. 11). Behind the front wall are the remains of at least three hut platforms, but no back wall. It is the orientation that is unusual. For one, the front wall faces west, but it was not possible to enter the walled area from that direction. The entrance instead is from the un-walled east, up a steep, heavily wooded slope devoid of residential debris. In fact, no obvious signs of occupation occur anywhere on the hilltop. This isolation and reversal indicate that Sojwane was probably a burial place, similar to the Chirongwa burial cave near Matendere in Zimbabwe (Huffman Reference Huffman1996, 172–4). The name dzimbahwe, one should remember, applies not only to the home of a sacred leader, but also to his court and grave (De Barros 1551, in Theal Reference Theal1898–1903, VI, 267). This is why prestige stone walling can be part of a burial complex. Ordinary people, in contrast, were buried in their settlements (e.g. Matanga in van Waarden Reference van Waarden1987). Presumably, Sojwane is the burial place of the senior leaders in the Motloutse valley. This is another new interpretation.

Figure 11. Sojwane interior.

We turn now to the chronology of these and other palaces and its application to political boundaries.

Chronology, politics and social statements

Khami period

Depending on boundaries, the areal extent of the greater Tuli region is some 16,800 sq. km, which is sufficient for two Level 4 districts. Another reconstruction places the Tuli area into four Level 4 districts, with one extending across the Shashe into Zimbabwe and another across the Limpopo into South Africa (van Waarden Reference van Waarden2012, 105–7). A Level 4 palace known as Little Mapela (Garlake Reference Garlake1968), however, stands near the Shashe-Shashani confluence in Zimbabwe, indicating a separate district. Little Mapela and Shape, then, each defended the boundaries of separate senior chiefdoms. Likewise, Level 3 palaces stand on either side of the Limpopo, indicating another boundary (Huffman & Hanisch Reference Huffman and Hanisch1987). The senior Tuli chiefdoms were therefore independent of their Zimbabwean and South African neighbours. Whether two or only one district existed during the Khami Period depends on the dates of individual palaces and associated commoner settlements.

Unfortunately, few Khami settlements in the greater Tuli area have been radiocarbon-dated. It is therefore necessary to examine stone-wall styles and decoration to establish a rough chronology. In the process, we give priority to the underlying construction principles rather than the visual appearance of the veneer.

At first glance, the walls at Sojwane appear to be P-coursing on the inside and poor Q-coursing on the outside. It is inconceivable, however, that the two veneers were built at different times. Rather, the uneven coursing is due to different-sized blocks that were not quarried. Furthermore, the visual appearance of the walling is conditioned by its location: on bare rock between large boulders. In this case, it is not possible to date the burial ground by its walling.

In contrast, check designs date several palaces to the Khami period. These include Motloutse, Sampowane and Upper and Lower Majande. It is noteworthy that these palaces also include retaining walls that formed house platforms. Such Platform-Type walls are typical of the Khami period and are on record at Breslau A and B in the Limpopo Valley (Huffman & Hanisch Reference Huffman and Hanisch1987), Chamabvefva, Maswingo and Rupunguhwe in the Buhwa area (Garlake Reference Garlake1970; Huffman Reference Huffman1978; Reference Huffman1979) and Danangombe and Naletale (MacIver Reference MacIver1906) in central Zimbabwe. Usually, a platform supports the messenger's office. The most dramatic example is at Naletale, where an ivory tusk once stood outside the front door (MacIver Reference MacIver1906, 54), even though the platform itself had a rough veneer to distinguish it from the lavishly decorated palace wall. Within our research area, platforms supporting the messenger's office occur at Lotsane, Marakalala, Upper and Lower Majande, Upper Mothudi, Phakwe 2 and Thune.

Some researchers have placed a few Tuli palaces in the Zimbabwe period because they have Q-coursing (e.g. van Waarden Reference van Waarden2012); for instance, Lotsane A and B. Both Lotsane palaces, however, have platforms on the front wall to support the messenger's office, so they are more likely to date to the Khami period. Upper Majande is another instance. In the latter case, blocked doorways and P-coursing in the southern wall are thought to represent an earlier occupation. Rather than P-coursing, however, the southern wall is simply rough coursing, probably denoting female activities and female spaces. Such use of rough coursing was common in the Khami period, serving gender purposes at Danangombe, Zinjanja and Chamabvefva (Huffman Reference Huffman1996). Moreover, the early dates at Upper Majande date rain-control activities rather than a Zimbabwe occupation.

What is more, blocked doorways do not provide conclusive evidence for earlier occupations. Blocked doorways occur in most dzimbahwe in our survey, but multiple occupations at most are unlikely. This observation also applies to Matendere built on bare granite, where excavations uncovered the remains of only one main occupation, yet many doorways had been sealed with stone (Caton-Thompson Reference Caton-Thompson1931, pl. LXV). Instead of rebuilding episodes, blocked doorways are more likely to mark the end of a palace's administrative use. Indeed, from a traditional viewpoint, doorways were closed when leaders shifted their headquarters (for whatever reason), or when leadership shifted to another ‘house’ and the new leader came from a different area (McEdward Murimbika pers. comm., 2018). A blocked doorway to sacred space was a way to deny access to potentially polluting forces. None of the dzimbahwe in the Tuli area, then, conclusively dates to the Zimbabwe phase. This is another new finding.

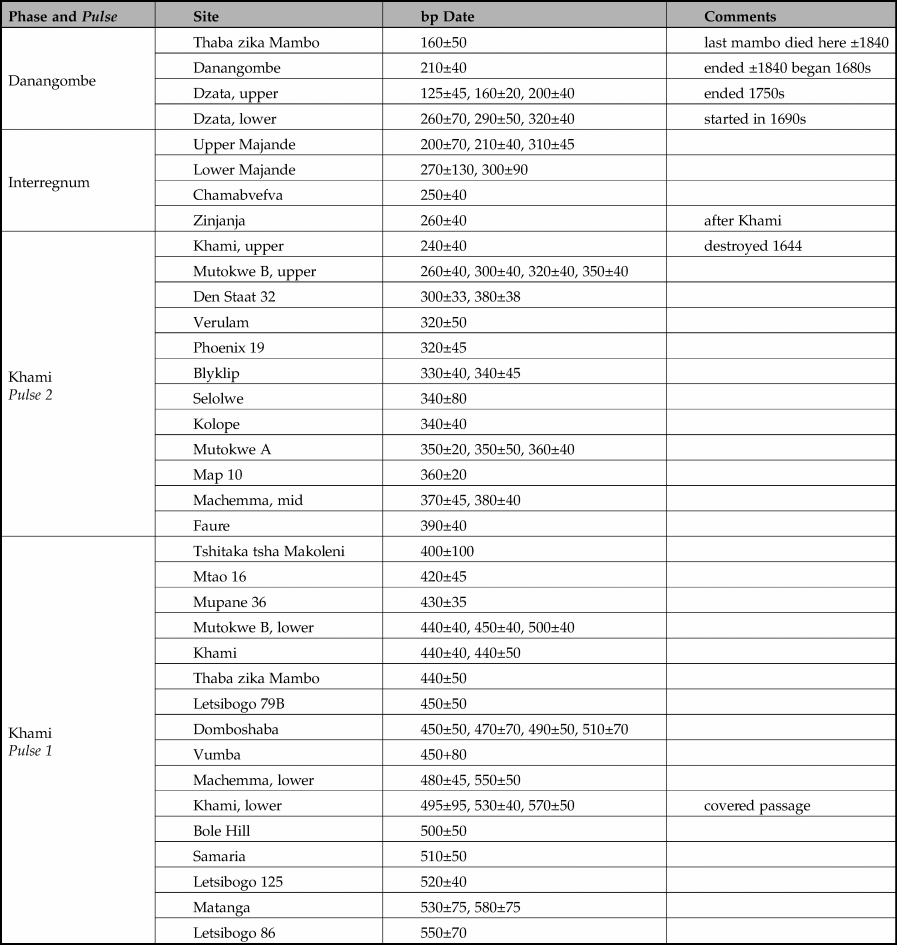

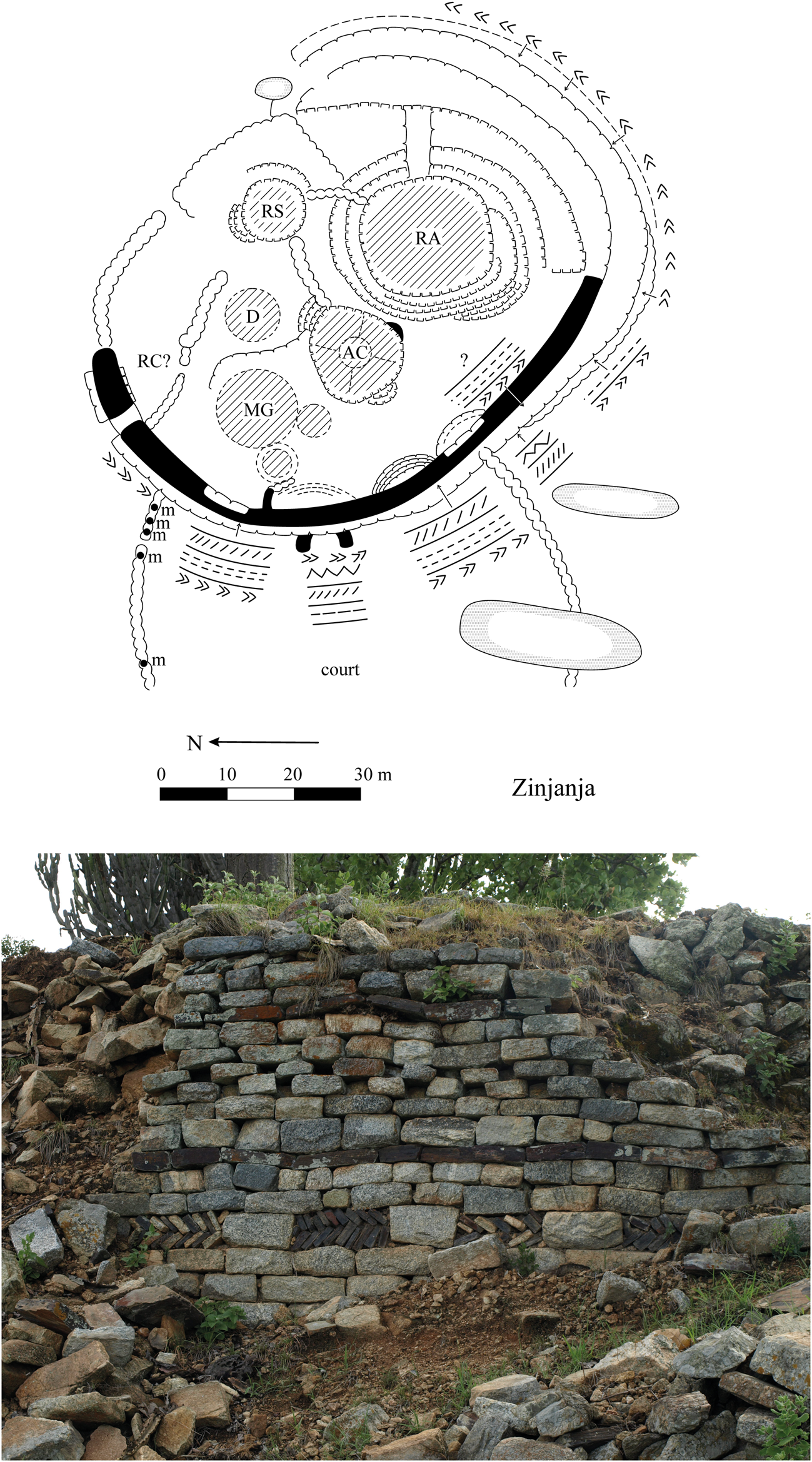

Van Waarden's research suggests a new Danangombe Phase should be recognized after Khami. To assess this new phase, some historical events become relevant. In about ad 1644, the Bayão expeditionary forces destroyed the palace at Khami as part of a civil war in Butua (Beach Reference Beach1980, 200–201). Archaeological evidence for this violence is impressive: it includes broken stone cannon-balls lying next to the shattered faces of terrace walls (Hall & Neal 1904), as well as vitrified daga walls and roof of the covered passage, caused by an intense fire (Robinson Reference Robinson1959, 44–6). Burnt thatch from an alcove at the back, furthermore, has been radiocarbon-dated to the mid seventeenth century (Tables 4 & 5), remarkably close to the documented date. A literal reading of the documents suggests that Bayão supported the Torwa (also Togwa) king against a younger brother. It makes more sense, however, that it was the usurper who sought Portuguese aid. This is because success on the battlefield, prior to the introduction of guns, was largely due to numbers. Since it is unlikely that any junior leader could muster more men than the king, the king probably won the first round, and it was the loser who turned elsewhere for help. Had it been the king who had first lost and then won the second round with Portuguese help, why did he not rebuild his palace at Khami, or build a new one there? Instead, the winner appears to have established his capital at Zinjanja, some 75 km away. A radiocarbon date (Pta-1549) from a post supporting the entrance to the palace places Zinjanja in the mid seventeenth century (260±40 bp) a couple of decades before Danangombe (Huffman Reference Huffman1976). Although large (Level 5 based on the palace), the commoner population at Zinjanja appears surprisingly small. Residential residue extends to the west (as it does at Khami), but it is not extensive. Considering the large size of the public court, it appears that the leader was making a false claim of importance. It is therefore unlikely that a powerful state ruled Butua after the Torwa and before the Rozvi.

Table 4. Khami Period occupational pulses in Tuli and Limpopo regions with relevant bp dates.

Table 5. Radiocarbon dates for Khami Period settlements, arranged by phase and pulse.

Following the political logic of the Zimbabwe Culture, the Rozvi capital was too close to Zinjanja (only 18 km) to have been contemporaneous. A radiocarbon assay (Pta-1914) from a wooden post in the covered entrance at Danangombe dates its beginning as the capital to the late seventeenth century (210±40 bp), slightly after Zinjanja. Moreover, documentary sources date the reigning Changamire's capital in Butua to the 1680s, about the same time as the wooden post. According to Rozvi tradition (Beach Reference Beach1980, 202), two Torwa rivals competed for power prior to the Rozvi take-over: each laid ‘claim to a hill as a symbol of their royalty’ (Posselt Reference Posselt1935, 142). Following this logic, van Waarden (Reference van Waarden2012, 103, 109) proposes that elaborate walling was the result of competition for followers.

Social changes in wall decoration

With this possibility in mind, a few more comments on decoration are in order. As other researchers have noted, palace decoration increased through time: Mapungubwe had none, dentelle characterized Great Zimbabwe, while profuse check designs covered the terrace walls at Khami. Later still, the front walls of Zinjanja and Naletale were covered in the whole range of designs expressing various aspects of sacred leadership.

A closer examination of the larger capitals shows that different locations follow the format noted at Naletale (Fig. 5). At Great Zimbabwe, female crocodile (herringbone) marked the stairway to the ritual sister, but male crocodile (dentelle) designated the stairway to the king, his chikuva (along with monoliths and engraved pillar), and the Eastern Enclosure where the famous Zimbabwe bird-stones were found, while the initiation centre in the Great Enclosure encompassed a quartet of symbols representing the four adult statuses: old and senior man (dentelle on the large tower), old and senior woman (small tower), young and fertile woman (multiple dark bands creating zebra stripes) and young and virile man (double chevron). Furthermore, V-shaped slots and a pile of dark stones signified pools in the context of women surrounding the two crocodiles (see Huffman Reference Huffman1996 for details). Smaller capitals contemporaneous with Great Zimbabwe, such as Matendere, followed the same format: male (dentelle) and female (herringbone) crocodiles marked the front, female crocodiles (herringbone) designated the ritual sisters’ compartment, and a pool design (dark band) was associated with the leader's private sleeping hut. There is thus every reason to believe that the core meanings remained the same throughout the history of the Zimbabwe Culture: it was the emphasis that changed.

At Khami, the sister's compartment was separate from the palace with herringbone, dark band and check on the front wall. Her access to the king was via a cyclopean stairway with herringbone at the top (White Reference White1899–1900, pl. IV). In contrast, profuse bands of check and a little cord (‘snake of the water’) covered the revetment terraces on the king's side (Fig. 12). Through time, some terraces were added or extended, but the message remained the same: a newer terrace (with three friezes of check), for instance, covered part of a higher terrace (with two friezes). Crocodile imagery was enhanced further by a sharp terrace corner to the left of the entrance passage on the messenger's platform: it is marked by one pool line and three crocodile motifs (Hall & Neal Reference Hall and Neal1902, opp. 214; Summers Reference Summers1971, opp. 19). This was intentional, for a similar free-standing feature is part of the mambo's side of the palace at Kubiku in eastern Zimbabwe (Huffman Reference Huffman1996, 32). While the icon for check imagery was the bumps on a crocodile's skin (Nettleton Reference Nettleton1984), this vertical feature derived from the ridges on its back. Other terraces at the back of the palace display more check (Summers Reference Summers1971, pl. 24), and then a zebra panel against a large boulder probably signified ‘the stone in the pool’—a reference to the blessing of fertility from God. Check designs also mark the king's ‘eye’ (guarding his back) and the king's brother in charge of the court (Vlei Enclosure) as well as the residence (Precipice Enclosure) of the man in charge of female labour. Thus, check imagery, that is male crocodile, was linked to the king and his officials.

Figure 12. Khami check imagery: front and back of palace.

As at Great Zimbabwe, the royal wives’ compound at Khami lacks decoration, although the confinement area (for the pregnant daughters of the king) had a pool design next to a tall natural boulder, while the initiation centre (Passage Enclosure) had the same status symbols as at Great Zimbabwe. Smaller Khami palaces also follow the same format. At Kongezi, for example, double chevron above check makes a striking entrance to the audience chamber where a wall incorporates a wide band of cord. As elsewhere, herringbone marks a compartment to the side that was probably occupied by the ritual sister (Huffman Reference Huffman1996, 70).

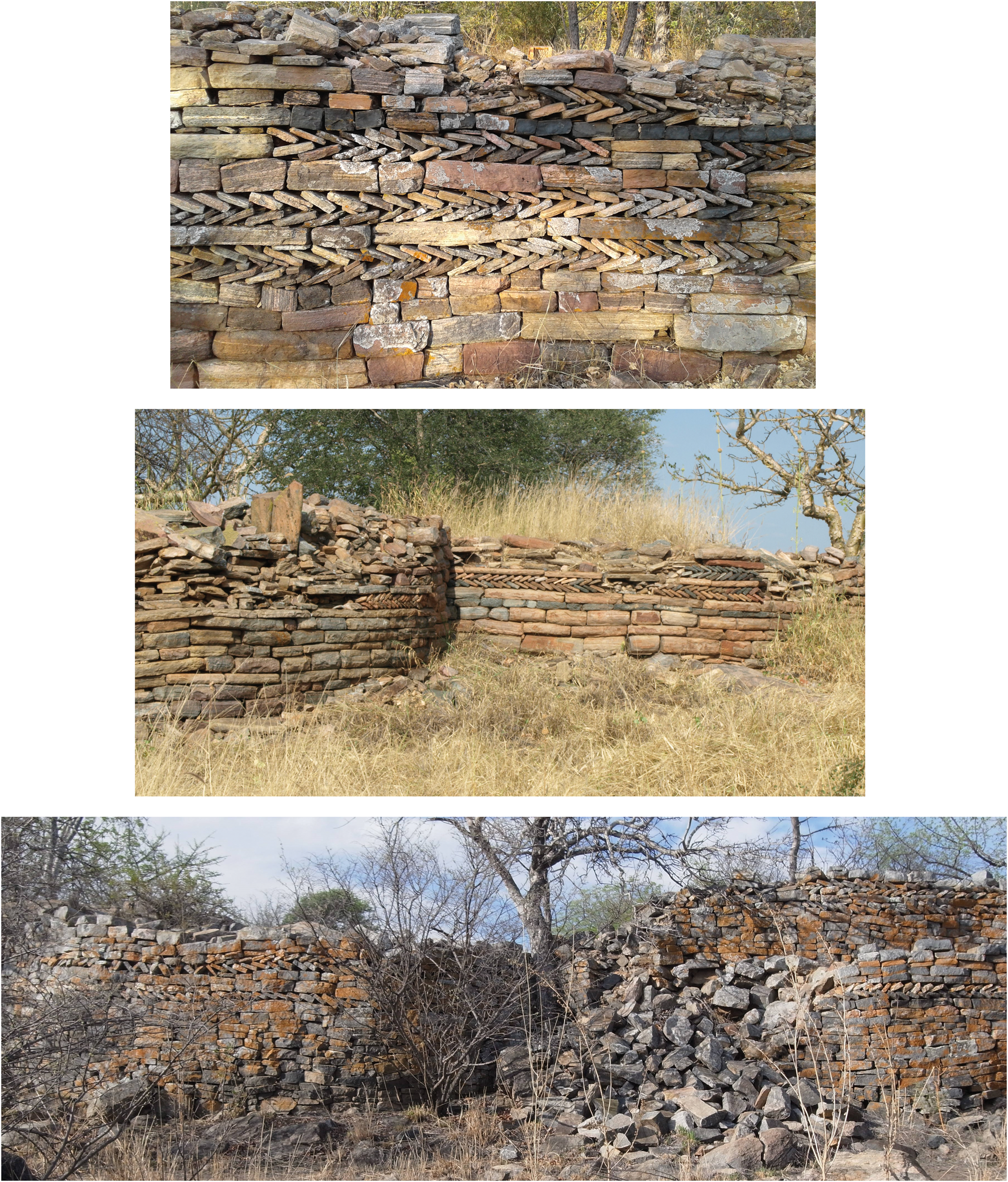

With the destruction of Khami and the end of powerful leadership for some 40 years, check designs became less prominent. At Zinjanja, rough coursing designates the female side of the palace in contrast to the highly decorated terraces on the king's side, especially facing the public court. There, in descending order, dark line, cord, dark line, narrow check, dark line and spaced herringbone emphasize snakes, pools and crocodiles. The court seat includes chevron, while spaced herringbone encircles the entire bottom of the king's side (Fig. 13). Several monoliths, signifying defence and justice, still stand on the court wall. The striking wall decoration at Sampowane and the two Majande palaces are more like Zinjanja than Khami. Here, rather than a dominance of check, it is herringbone and cord which are prominent (Fig. 14). Check designs occur, but as a narrow band rather than a wide frieze. The initiation centre and interior palace at Old Tati have a similar use of herringbone and these four sites may be more-or-less contemporaneous with Zinjanja. Their similarity is not just in the amount of decoration, but also in content.

Figure 13. Zinjanja: (above) palace plan; (below) court walling. (After Huffman Reference Huffman1996.)

Figure 14. Palace walls during the Interregnum phase. From top: Lower Majande, Upper Majande and Sampowane.

Perhaps the change from a predominance of check—the senior male status—to multiple designs represents a change from the majesty of leadership and personal power to an emphasis on sacred duties. Chevron (snake of the mountain) refers to the mambo's duty to provide rain and thus bounty from the earth, while the predominance of cord (snake of the water), dark line (pool) and herringbone (female crocodile) refer to the ritual sister's responsibilities towards female fertility. In addition to her duties as a national advisor, the senior sister was responsible for human fertility through her female ancestors. This in turn included the proper moral behaviour of royal daughters and their desirability as marriage partners. Thus, if Zinjanja and other large political centres were competing for followers, they were not advertising their political power, but their efficacy as sacred leaders—guaranteeing prosperity through their link to the ancestors and God.

This shift from power to gendered responsibilities may be why some dzimbahwe, such as Lower Majande, were built on level ground rather than a hilltop. Not far from Zinjanja, the Level 4 palaces of Nsalansala and Shangangwe were also built on level ground and the interiors of both bear profuse herringbone and cord designs: check here was reduced to one or two lines, or spaced blocks (Huffman Reference Huffman1996, 69, 71).

Danangombe appears to reverse this trend. Rising from level ground, the huge palace is a raised platform that to enter, one must climb a stairway to a covered passage supported by wooden posts. Moreover, check designs return in greater abundance (Fig. 15). Decorations on the three terraces facing the court, for instance, emphasize the senior male status. On the top terrace, cord (snake of the water) runs above a single chevron (snake of the mountain) which in turn overlies a long wide band of check (male crocodile). On the second terrace, cord again overlies a long line of check, and on the third and final terrace a pool design (dark line), or collapsed snake, runs across three lines of check. At the front, a crocodile frieze (over cord and dark line) marks the mambo's side of the palace, along with a sharp right-angled corner (with chevron, cord and check) like that at Khami. Prominent crocodiles also occur on the sister's side of the entrance. According to old photographs (Hall & Neal 1904, opp. 284; MacIver Reference MacIver1906, pl. XVII), three pool designs led to other motifs: the upper pool led to check above cord; the second to herringbone spaced by colour; and the third pool design extended over a wide panel of check. This panel led in turn to a tall double frieze of pool, female crocodiles (spaced herringbone) and male crocodiles, which echo the double motifs of ‘old woman’ on Shona divining dice (Tracey Reference Tracey1934). In addition to these palace symbols, the office of the brother in charge of the court, standing alone on a prominent platform, bears three variations of crocodile designs (and one line of cord). The court wall itself bears the symbolic triad of ‘crocodile (check) in its pool (dark line) guarded by a giant snake (cord)’. At Naletale, this triad also marks the court wall. The front wall, as we have seen, also emphasizes crocodiles, snakes and pools, while other designs follow the standard format: herringbone on the sister's side and spaced herringbone for the young wives. What is different from Zinjanja is the size of the check: the friezes are wide rather than narrow. New radiocarbon dates for the mambo's platform (e.g. D-AMS024217 – 189±30 bp) suggest that Naletale probably housed an important district leader under the Rozvi mambo at Danangombe (Koleini et al. Reference Koleini, Machiridza, Pikirayi and Colomban2019; Machiridza Reference Machiridza2020). These occurrences suggest a renewed emphasis on kingship and power.

Figure 15. Danangombe check imagery. (Top and middle) mambo's side of the palace; (bottom) ritual sister's side.

This second change in meaning parallels the return of centralized control with the Rozvi state under the powerful Changamire Dombolakonachingwano. The sequence, then, is the following:

• the senior male status (dentelle and check) designated the headquarters of powerful states based at Great Zimbabwe and Khami;

• the absence of a powerful state at Zinjanja was linked to an emphasis on responsibilities (herringbone, cord, dark band and chevron);

• the return to senior male status (check) at Danangombe was connected to the rise of a new state.

To accommodate these changes in meaning, it will be convenient to recognize two new phases in the Khami Period: an Interregnum Phase (ad 1650–1680) with Zinjanja as the major capital and an emphasis on sacred duties; and a later Danangombe Phase (ad 1680–1840) with emphasis on power. Three phases in all—Khami, Interregnum and Danangombe—impact our understanding of political territories.

Political boundaries

Although core territories were unlikely to have changed through time, since they were bounded by rivers, size and internal hierarchies could have changed as states expanded or contracted. Because of such shifts, it is difficult to know which settlements were contemporaneous and thus their population sizes. We can nevertheless make a rough estimate. If we take one well-researched area (between the Kolope stream and Mapungubwe), divide the number of agricultural villages (107) by three (the number of shifting capitals), multiple by 50 people per homestead (107 ÷ 3 × 50) and add the capital (300), we reach a total of about 1783 people per petty chiefdom (one half children). This estimate compares favourably with the recorded figures for the Tlokwa in the 1930s: a total of 1800 ruled by one petty chief and four headmen (Ellenberger Reference Ellenberger1939). This is also similar to the Khami chiefdom at Letsibogo: one petty chief, two or three royal headmen and 42 commoner homesteads, totalling some 2550 people. At the next level, there were 39,000 Ngwaketse in the 1930s ruled by one senior chief, three petty chiefs and 133 headmen (Schapera Reference Schapera1942). This is a reasonable population structure for the Level 4 chiefdoms based at Lepokole, Mantswe, Motloutse, Shape and Thune, especially considering that court hierarchies are not constrained by ethnicity.

Motloutse appears to have been more recent than Shape and Lepokole and its district probably incorporated the highly decorated Sampowane and Upper and Lower Majande. Other highly decorated dzimbahwe, such as Tati (Huffman Reference Huffman1996, 93; van Waarden Reference van Waarden2012, 92), probably also date later. The available radiocarbon dates place them in the Interregnum Phase, before the Rozvi.

Because the domestic economy was based on agriculture, climate would have affected occupation intensity. Significantly, rainfall fluctuations recorded in Limpopo baobabs (Woodborne et al. Reference Woodborne, Hall, Robertson, Patrut, Rouault, Loader and Hofmeyr2015) would have also been similar in the greater Tuli region. A combination of these rainfall data with wall styles and decoration yields three likely occupation pulses (Table 4):

• Pulse 1 was between ad 1400 and 1475 (400–500 mm) and included the lower levels of Machemma, the Letsibogo chiefdom and Little Mapela.

• Pulse 2 occurred during another good rainfall (400–700 mm) period between about ad 1520 and 1590 (with a peak around ad 1550) and included the middle levels of Machemma.

Both pulses occurred during the Khami Phase. No one may have lived in the drier regions (200–300 mm) between ad 1610 and 1620. Settlement could have resumed in the 1630s (300–400 mm), but the 1650s received little rain (200-300 mm) after the destruction of Khami. Indeed, a major drought around ad 1650 is reflected in burnt granaries and houses over a wide area of southern Africa, especially among Tswana-speaking communities in the Mochudi and Madikwe areas (Huffman & Woodborne Reference Huffman and Woodborne2016). Rainfall was generally higher in Zimbabwe, and Zinjanja dates from the 1650s and Danangombe from the 1680s through to about ad 1840.

-

• Pulse 3 in the Tuli area received higher rainfall (400–500 mm) in the late 1660s. The two Majande palaces, dating to between ad 1640 and 1680, were built during this third pulse.

This third pulse occurred during the Interregnum Phase. By the 1690s, precipitation had dropped substantially (±250 mm). Overall, rainfall progressively decreased throughout southern Africa from about ad 1600, hitting a low point 100 years later—the nadir of the ‘Little Ice Age’. Few if any farmers could have lived in the greater Tuli area at that time. Indeed, the Danangombe Phase is not present in Tuli nor the Limpopo Valley. As van Waarden (Reference van Waarden2012, 241) noted for further north, no archaeological evidence exists for a Rozvi occupation because it would have been too dry for agriculture.

Our final point concerns territorial boundaries. If the Motloutse and Lepokole headquarters were in the middle, then Shape and Thune were probably located closer to the eastern and western boundaries. As noted, reasons for shifting a capital include changes in leadership. Such shifts sometimes mean a change from one royal house to another, typically to that of a brother. Normally, leadership passed from father to son (contra Chirikure et al. Reference Chirikure, Manyanga and Pollard2012), but occasionally from brother to brother when a son was not available (e.g. Dos Santos 1609 in Theal Reference Theal1898–1903, VII, 191). In this case, the new leader may have placed his headquarters in his own family area where he previously enjoyed the most support. Alternatively, if rival leaders posed a threat, one or both may have wanted to defend his boundary because of the need to provide commoner communities with easy access to essential services, such as the court; otherwise, commoners may switch their allegiance (McEdward Murimbika pers. comm., 2010). Whatever the reasons were, if Shape and Thune were near boundaries, the district encompassed from 11,000 to 13,000 sq. km, well within the range of Level 4 districts. The boundaries may have ebbed and flowed somewhat for environmental and political reasons, but probably not much. Whatever the exact size, Marakalala appears to have been an isolate and may well have been independent.

Without radiocarbon dates, we cannot assign most dzimbahwe to the three occupation pulses. We can nevertheless offer some general comments. The two Level 4 headquarters in the territorial centre (Lepokole and Motloutse) probably each dated to a separate pulse. Because of the Little Mapela date, Shape may also date to Pulse 1. Thune may then date to one of the next two pulses. With three main pulses in one territory, we would expect three to four Level 3 petty chiefs in each pulse and the same number under each of the five senior chiefs. The total number of Level 3 palaces, ±19, conforms to this expectation, especially considering possible shifts in leadership and movement of commoners to new arable land. The proximity of Phakwe 1 and 2, Upper and Lower Mothudi, and Thune and Mantswe, suggests that some chiefs (and their associated commoners) returned to the same areas when local climate improved.

Our re-assessment highlights the importance of five factors: cultural principles, climatic data, walling types, spatial organization and the meaning of wall designs. Thus, equal-distant polygons are inappropriate for the Zimbabwe Culture: they do not accurately reflect political territories. Instead, natural features such as rivers served that purpose. In addition, rainfall fluctuations made the greater Tuli region periodically unsuitable for farming. Furthermore, types of wall construction have more chronological salience than visual appearance, while palaces, wives’ compounds and initiation centres were organized differently. And lastly, emphases in wall designs changed through time. All five factors impact relevant classifications.

Acknowledgements

Over the years, several people helped with the fieldwork. These include Alec Campbell, James Denbow, Edwin Hanisch, Tim Maggs, Hannali van der Merwe and Catrien van Waarden. Mike's wife Kirsten assisted on numerous occasions. We thank Jan Boeyens, Gavin Whitelaw and McEdward Murimbika for comments on the text. Bashi Kikia, Gaborone, supplied the drone photographs used to make plans of Mmadale and Phakwe 2. Wendy Voorvelt prepared the illustrations. Fieldwork was supported by the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (HUFF013). Our interpretations do not necessarily reflect the opinions of these commentators and sponsor.