Cross-cultural interactions in the colonial era often witnessed translations of culturally distinct concepts. Captain James Cook's reception as the Polynesian god Lono when he landed at Kealakekua Bay during a Hawaiian festival, and his death when he later returned out of season, is a well-known example (Obeyesekere Reference Obeyesekere1992; Sahlins Reference Sahlins1985; Reference Sahlins1995). ‘Translations’ from one cultural world to another are also evidenced in rock-art practices around the world, though an uncanny resemblance between two culturally distinct notions is rare. The South African unicorn is one such example, and the story (or at least one side of it) begins as early as 77 ce, when Pliny the Elder described the Indian ‘monoceros’ as impossible to take alive and having the body of a horse with a single black horn projecting from its forehead (Bostock & Riley Reference Bostock and Riley1855, 281). Remarkably similar notions of an uncatchable, dangerous, single-horned horse-like creature persisted among colonial South Africans over a millennium and a half later.

Europeans sought unicorns and rock paintings of them almost as soon as they set foot on the shores of southern Africa. Their interest stemmed from their cultural beliefs, which they transposed onto the African continent and its people (Smith Reference Smith1968, 98; Voss Reference Voss1979, 4). Against this Western backdrop, many early travellers searched for rock paintings of unicorns, which some considered evidence of the creature's existence (Baines Reference Baines1864, 171–2; Barrow Reference Barrow1801, 302, 303, 311ff; Brown Reference Brown1870, 367; de Jong Reference de Jong1802, 201–3; Godée Molsbergen Reference Godée Molsbergen1932: 174; Gordon Cumming Reference Gordon Cumming1859, 69; Kennedy Reference Kennedy1961, 167; Reference Kennedy1964, 20; Le Vaillant Reference Le Vaillant and Helme1790: 156–7; Leslie Reference Leslie1830; Lichtenstein Reference Lichtenstein and Plumptre1812, 167–8; Moodie Reference Moodie1866, 86–7; Paravicini di Capelli Reference Paravicini di Capelli and de Kock1965, 145–6, 252; Phillips Reference Phillips1827, 131–2; Schutte Reference Schutte and Böeseken1982, 296–7, 420–421; Smith Reference Smith1968; Sparrman Reference Sparrman1785, 147–51, 161; Steyn & Steyn Reference Steyn and Steyn1962, 27; Reference Steyn, Steyn and Aucamp1971, 2; Voss Reference Voss1979; Wallis Reference Wallis1946, 610–11, 719–20; Ward Reference Ward1997, 83; Wyley Reference Wyley1859). Rock paintings have thus played a significant role in South Africa's unicorn lore (for general summaries, though with inadequate discussions of the rock art, see Smith Reference Smith1968; Voss Reference Voss1979; Burgess Reference Burgess2019). Ultimately, however, the images were dismissed as depicting figments of the imagination.

For centuries, colonial beliefs about unicorns silently mixed with indigenous ones. But, whereas physical proof became a Holy Grail, indigenous beliefs were regarded sceptically as rumour or hearsay. Without realizing this distinction, European colonists sought after the unicorn, assuming, at least initially, that it was the creature they knew. There were, however, signs that this was not the case. For example, Lady Anne Barnard, socialite and sometime colonial secretary at the Cape, wrote a letter in 1797 to the Scottish politician and advocate Henry Dundas, an extraordinary part of which reads:

Some years ago, some of the nativesFootnote 1 had expressed their surprise at seeing it [the unicorn] in the King's arms, and when they were asked if they would procure such an animal for a sum of money they had shuddered, saying, ‘Ay, to be sure,’ but he was ‘their god’. (Wilkins Reference Wilkins1910, 77)

A Scottish unicorn has appeared alongside an English lion in the British royal coat of arms since the beginning of the seventeenth century with the coronation of James VI of Scotland as James I of England. Remarkably, however, when looking upon the arms of George III, King of Great Britain from 1760 to 1801, indigenous South Africans did not see a foreign king's creature, but a local one. The importance of this observation has been missed for over 225 years. Consequently, travellers, missionaries and researchers alike have not realized the full significance of depictions of one-horned antelope. In this paper, rock paintings, documentary sources and ethnography collectively lead to a novel understanding of how indigenous and Western beliefs can intersect.

Searching for unicorns

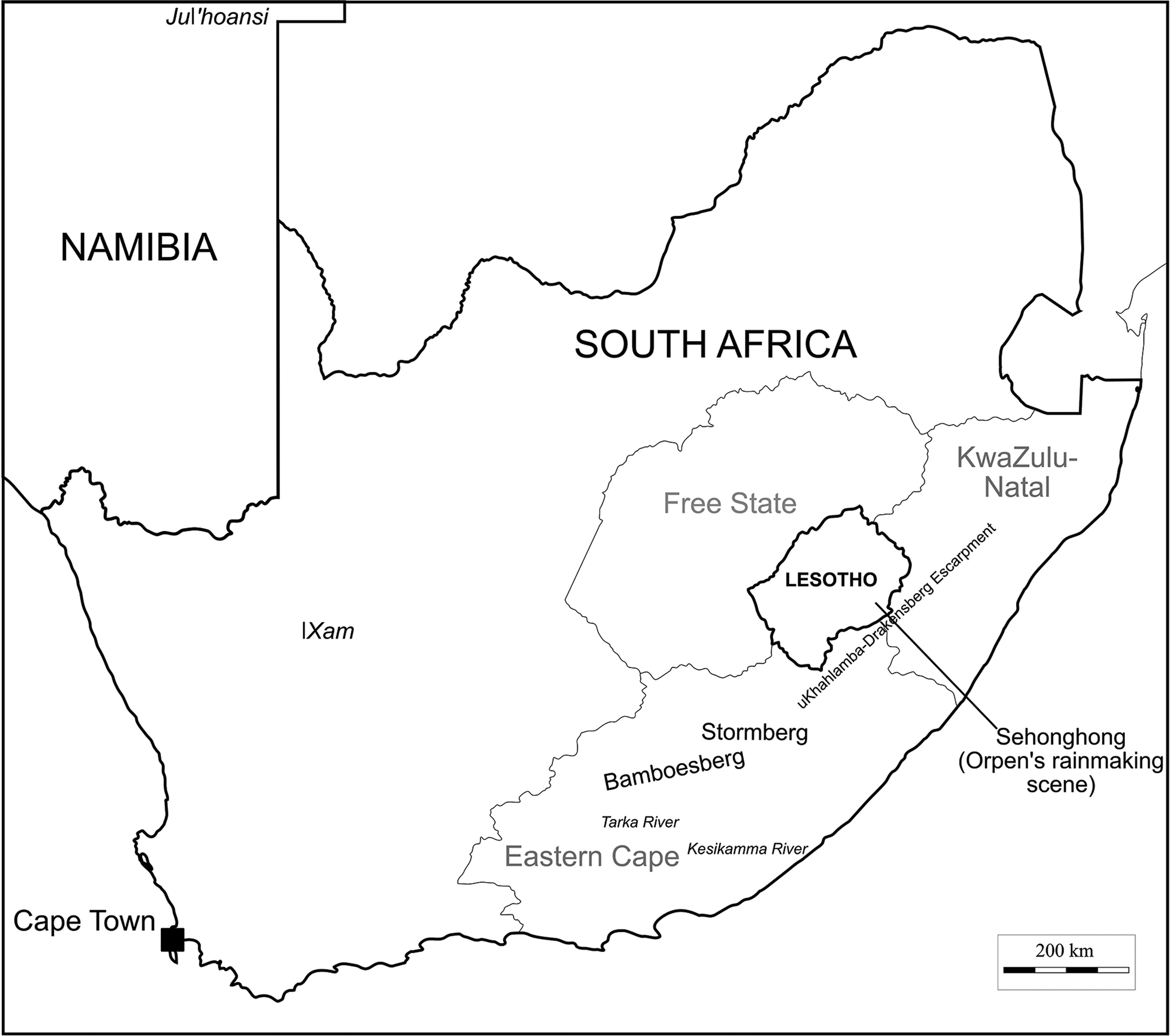

Perhaps the most famous South African search for unicorns was reported by John Barrow, ‘Late Secretary to the Earl of Macartney, and Auditor-General of Public Accounts, at the Cape of Good Hope’ (Barrow Reference Barrow1801, frontispiece). He sought evidence for real rather than fanciful unicorns, which he considered of potentially biblical importance to natural history (Barrow Reference Barrow1801, 314–15). Any biological specimen would therefore have had a place in the nascent world of European science. Barrow thought the ‘living original’ might yet be found north and east of the Bamboesberg mountain range in what is today the Eastern Cape Province (Fig. 1). There, ‘the people [Bosjesmans or Bushmen] who make them [the paintings] live’ (Barrow Reference Barrow1801, 303, 315). Although he managed to arouse some enthusiasm for an expedition to go in search of it (Barrow Reference Barrow1801, 313), he never ventured east outside the Colony (maps in Barrow Reference Barrow1801 and Reference Barrow1806a (I)).

Figure 1. Map of South Africa showing places mentioned in the text. (Image: author.)

Some locals he met claimed to know about unicorns (Barrow Reference Barrow1801, 302–3, 311–13). We cannot know exactly who Barrow's informants were (probably ‘native’ and ‘Dutch’ peasants) or how much was lost in linguistic and cultural translation. Nevertheless, the beast differed from African rhinoceroses:Footnote 2 it was a ‘solidungulous animal resembling the horse, with an elegantly shaped body, marked from the shoulders to the flanks with longitudinal stripes or bands’ (Barrow Reference Barrow1801, 315). At the time, he thought that rock paintings of unicorns must depict biological animals rather than ‘creatures of the brain’ (Barrow Reference Barrow1801, 314). Today, however, we know that non-real (in the sense of observable reality) beings are prominent in San rock art.

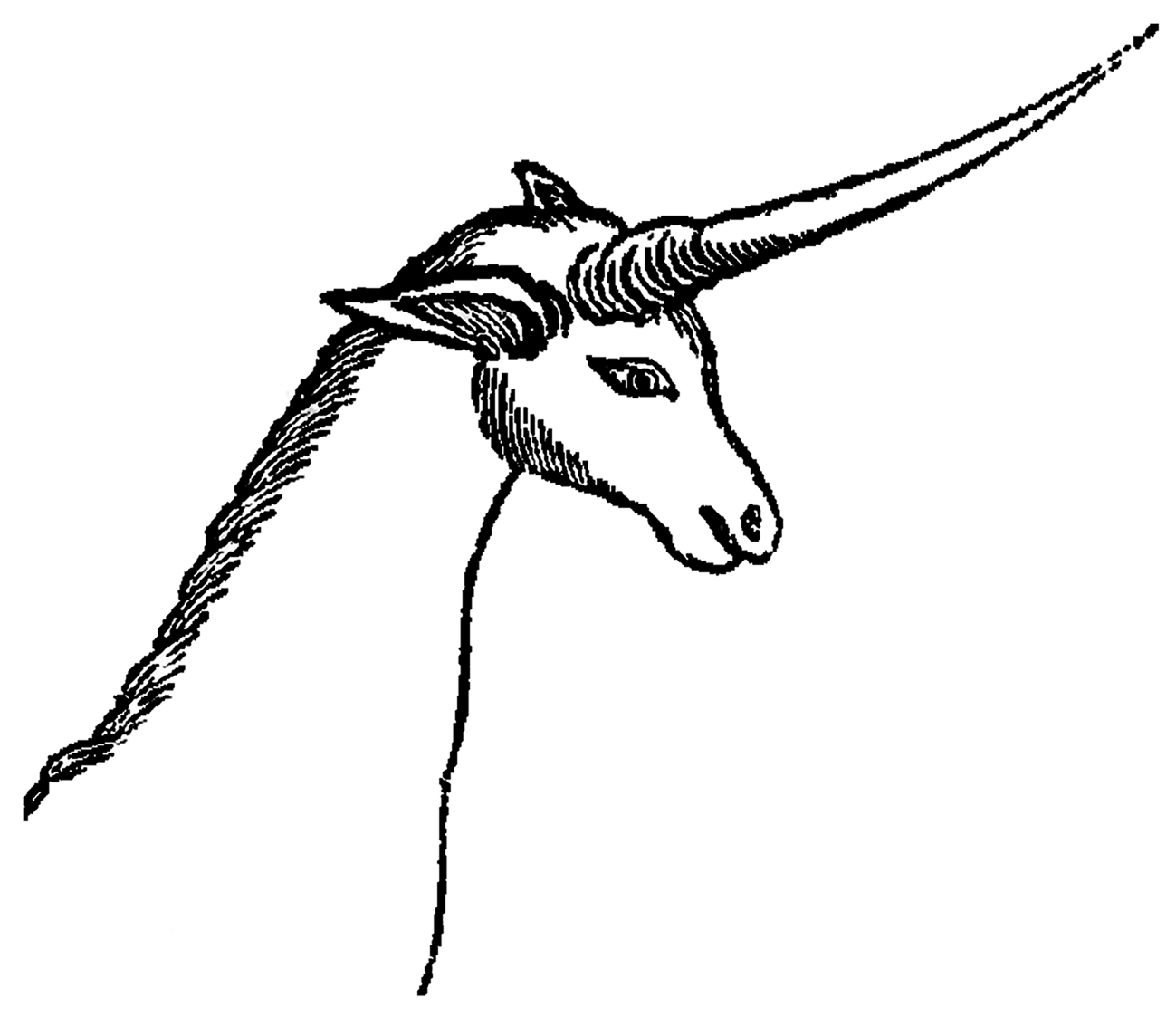

Barrow visited several rock-shelters unsuccessfully, following assertions by ‘one of the party’ and ‘many of the peasantry’ who claimed to have seen paintings of unicorns (Barrow Reference Barrow1801, 302, 303, 311). Then, on 15 December 1797, his party found one in the mountains along the Tarka River (Barrow Reference Barrow1801, 311–14). He published a ‘fac simile’ of the original (Fig. 2), noting that ‘[t]he body and legs were concealed [superimposed] by the figure of an elephant that stood directly before it’ (Barrow Reference Barrow1806a (I), 269). The facsimile is notorious, having been regarded sceptically for decades (Knox-Shaw Reference Knox-Shaw1997, 20; Smith Reference Smith1968, 101; Steyn & Steyn Reference Steyn and Steyn1962, 27; Wintjes Reference Wintjes2014, 698). Many have argued that Barrow misinterpreted an image of a two-horned antelope. Some suggest that he ‘may have been somewhat out of touch with local realities’ and that his unicorn was nothing more than a misconstrued eland antelope (Steyn & Steyn Reference Steyn and Steyn1962, 27). Similarly, Justine Wintjes (Reference Wintjes2014, 698) suggests that

[w]hether Barrow truly ‘saw’ an image of an animal with one horn (which might, for example, have been a partially preserved antelope with only one horn clearly visible), it is obvious from his words that he interpreted this subject matter from a depiction that was not very clear (or incomplete).

Anthony Voss claims, even though white rhinoceroses have two horns, that ‘Barrow did not know of the white rhinoceros, and he refused to accept that the African rhinoceros was the Bushman's unicorn’ (Voss Reference Voss1979, 6–7, cf. Barrow Reference Barrow1806a (I), 271). Peter Knox-Shaw (Reference Knox-Shaw1997, 21–2) accuses Barrow of faking his facsimile, and defers to contemporary rock-art researchers to point out that

[t]he cave containing Barrow's unicorn has not been found, but most one-horned beasts painted by the San turn out to be gemsbok, and other misreadings may have been caused by the disappearance of pale pigment below the dark nape-line of eland. (Knox-Shaw Reference Knox-Shaw1997, 20)

[Knox-Shaw was] indebted to H.C. Woodhouse for the first of these suggestions, to Professor [David] Lewis-Williams for the second. (Knox-Shaw Reference Knox-Shaw1997, note 12)

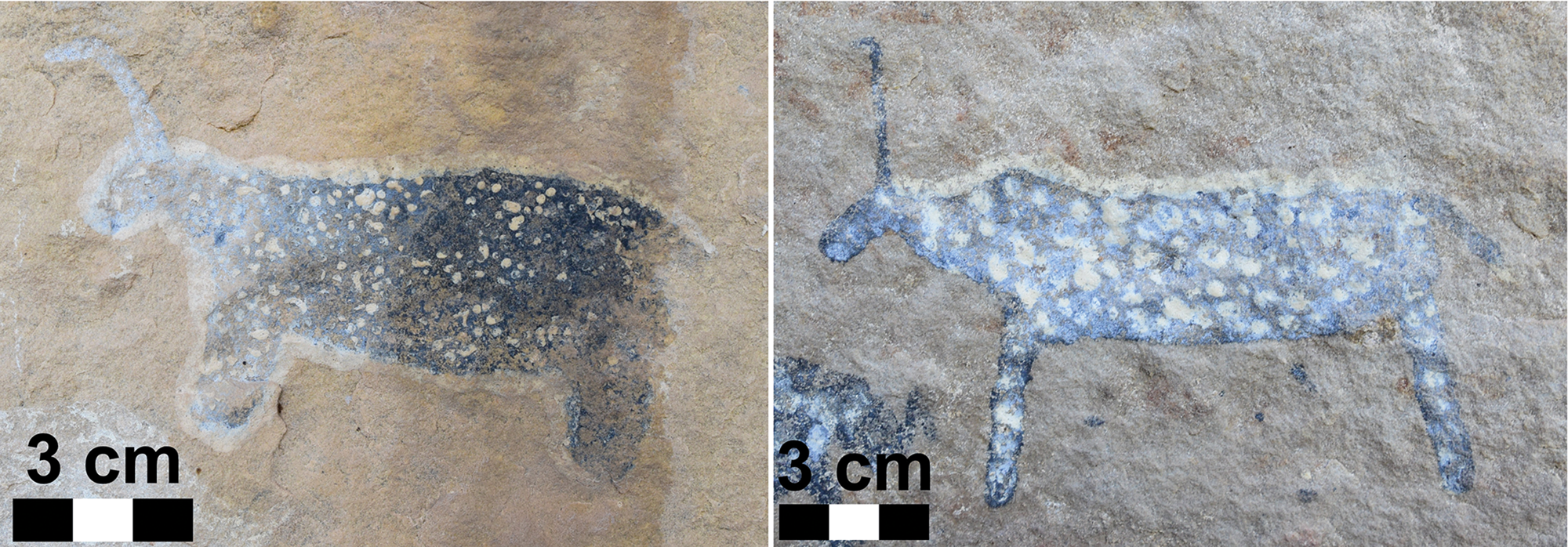

While it is true that we are yet to relocate Barrow's unicorn, the nature of ‘misreadings’ requires discussion. Gemsbok antelope (Oryx gazella) do not inhabit the part of South Africa where Barrow claims to have found his painting.Footnote 3 To my knowledge, gemsbok do not feature (at least not prominently) in the rock paintings of the north Eastern Cape. More importantly, researchers today know that even when the fugitive white paint in an eland image disappears, the red or yellow body remains. Such images often have a tail, which hangs down, and, at the opposite end, a nape-line extending out from the animal's back (Fig. 3). Unfamiliar viewers can easily misconstrue the nape-line as a single horn.

Figure 2. Barrow's ‘fac simile’. The illustration employs a combination of Western aesthetic conventions alien to San rock art and was probably not engraved by Barrow himself (Steyn & Steyn Reference Steyn and Steyn1962, 27; Wintjes Reference Wintjes2014, 698). (After Barrow Reference Barrow1801, 313.)

Figure 3. Partially preserved images of eland are sometimes misidentified as unicorns. The white paint of the upper eland is almost invisible compared to the lower one. Each animal has a vertical red tail (left) and a horizontal nape-line (right). (Photograph: author.)

The cynical views of Barrow's and other unicorn images are partly rooted in a perspectival argument: because the animal is depicted side-on, one horn obscures the second. It is one of threeFootnote 4 explanations that arose when, unsurprisingly, the ‘real’ unicorn was not found (Smith Reference Smith1968, 105–8; Voss Reference Voss1979, 10–12). One claimed, as we have seen, that the rhinoceros had been the unicorn all along (Burchell Reference Burchell1824, 77; Campbell Reference Campbell1822 (I), 294–26; (II), 335; Gordon Cumming Reference Gordon Cumming1856, 216; see also Smith Reference Smith1838, Rhinoceros keitloa). A second, which we have also encountered, suggested that the gemsbok was the inspiration behind the unicorn because one straight horn covers the other when viewed from a lateral perspective, and males often lose a horn in the rutting season (Andersson Reference Andersson1856, 281; Gordon Cumming Reference Gordon Cumming1856, 93–4; Harris Reference Harris1838, 84, 309; Reference Harris1840, pl. IX; Steedman Reference Steedman1835, 119–23; see also Millais Reference Millais1899, 199). A third claimed that the unicorn had never existed outside imagination (Burchell Reference Burchell1824, 77). Though this third explanation resembles the contemporary understanding of unicorns, all three explanations are based entirely on the European search for a European idea.

Importantly, the perspectival argument was refuted over a century-and-a-half ago. The English traveller and artist Thomas Baines noted (correctly) that San images of two-horned animals invariably have two horns (Kennedy Reference Kennedy1961, 167; Reference Kennedy1964, 20). Baines thus recognized that San images faithfully represent whatever the image-makers wanted to depict (Witelson Reference Witelson2018, 197). Whatever perspectival ‘errors’ may be perceived, the painters ‘never fail to give each animal its proper complement of members’ (Baines Reference Baines1864, 171, emphasis in original; see also Wallis Reference Wallis1946, 719–20).

Previous writers have paid inadequate attention to rock paintings when considering South Africa's unicorn lore. Some writers, like Anna Smith (Reference Smith1968, 103), tacitly employ the perspectival argument by treating reports of unicorn rock paintings as mere rumours, apparently because, in addition to the unsuccessful, mythologized searches for the creature itself, her own ‘search through modern works on prehistoric art in South Africa … yielded no recorded picture of a one-horned animal that could be taken for the unicorn actually found in situ in this century’ (Reference Smith1968, 103). Though Smith does not say so, her allusion to a specific century suggests that, like Voss (Reference Voss1979, notes 18 and 49; see also Knox-Shaw Reference Knox-Shaw1997; 20), she was aware of but unconvinced by George William Stow's copies of rock paintings from the late nineteenth century, some of which do depict one-horned antelope (Stow & Bleek Reference Stow and Bleek1930). Stow's copies date from around the same time as Joseph Orpen's (Reference Orpen1874) well-known copy of the rainmaking scene at Sehonghong, Lesotho. More significantly, however, many writers have ignored Helen Tongue's twentieth-century copies of one-horned antelope from sites in the Stormberg to the east of the area in which Barrow found his painting (Tongue Reference Tongue1909, pls VI, no. 8 and XVIII, no. 29). Tongue's copies were interpreted ethnographically by Dorothea Bleek, who was familiar with Stow's copies and ǀXam San commentaries on them (Stow & Bleek Reference Stow and Bleek1930). Importantly, Bleek was probably the first rock-art researcher to realize, in light of San beliefs, that images of one-horned antelope are actually depictions of rain-animals (Stow & Bleek Reference Stow and Bleek1930; Tongue Reference Tongue1909), though the point typically goes unacknowledged (e.g. Smith in Bassett Reference Bassett2008, 58; Challis & Sinclair Thomson Reference Challis and Sinclair Thomson2022; Pinto Reference Pinto2014; Sinclair Thomson Reference Thomson2021, 66).

Close attention to the paintings themselves highlights a critical weakness of the perspectival argument: unambiguous one-horned creatures are depicted in San rock art. Some examples show the single-horned head en face rather than from the side (Figs 4–6). By implication, the many lateral perspective examples, some of which have two (front and back) legs rather than four, must also depict one-horned creatures. There are shaded and unshaded examples of these beings, suggesting that the concept had a precolonial origin (Witelson Reference Witelson2022, 265ff). Collectively, they suggest that Barrow probably did see a rock painting of a one-horned creature and correctly identified it as such.

Figure 4. A little-known sketch by Elske Maxwell-Pienaar of a rock painting at a shelter near the town of Burgersdorp. Original scale: 9.5 × 8 cm. (After Steyn & Steyn Reference Steyn, Steyn and Aucamp1971, 2.)

Figure 5. A drawing of a group of one-horned antelope shown from a variety of perspectives. The leftmost animal in the top row has two sets of tusks, which are also seen in some rock paintings of rain serpents. The inset image shows a photograph of the head of the en face animal. From a rock shelter south of Flaauwkraal, Eastern Cape. (Image: author.)

Figure 6. One-horned antelope shown from various perspectives at a site southeast of Molteno. The necks of the two animals in the top left corner are turned, confirming that each head has one horn only. Note the yellow and white serpent. (Photograph: courtesy of Stephen Townley Bassett.)

Scepticism about images of one-horned creatures usually goes hand-in-hand with a dismissal of indigenous beliefs. Voss, for example, does this despite being aware of the ‘unsolicited evidence’ in Barrow's account and those of other early travellers: ‘[i]n these reports the unicorn is, with rare exceptions (such as Lady Anne Barnard's account … [sic]), mentioned as just another animal’ (Voss Reference Voss1979, 4, note 13, parentheses in original). Similarly, Knox-Shaw calls Francis Galton a ‘willing dupe’ for believing some northern San who mentioned a unicorn (Knox-Shaw Reference Knox-Shaw1997, 18). He also claims that ‘[a]s far as [San] ethnography is concerned, the unicorn seems not to feature at all (Knox-Shaw Reference Knox-Shaw1997, 20), adding that ‘[n]o San word is recorded, and the roundabout Xhosa word,—ihashelentsomi-elinophondo ebunzi (the mythical horse with a single horn on its brow)—suggests cultural translation’ (Knox-Shaw Reference Knox-Shaw1997, note 13). Yet, as I will show, these previous writers overlooked relevant evidence in ǀXam ethnography and ǀXam comments on Stow's copies.

Revisiting the South African unicorn

Beliefs in a one-horned animal appear to have been widespread and, to a certain degree, transcultural in southern Africa. Several documentary sources resemble each other closely, and it is possible that, if the details did not originate in colonial hearsay, their writers might have ‘borrowed’ information from earlier sources (Smith Reference Smith1968; cf. Dowson et al. Reference Dowson, Tobias and Lewis-Williams1994). Nevertheless, the sum of this cumulative evidence is substantial.

Some records merely note that indigenous people, as well as colonists, knew of such a creature. We have already seen that Barrow (Reference Barrow1801, 315) learned about the creature's striped, horse-like appearance from local ‘peasantry’. A similar description was given by Hendrik Cloete of Groot Constantia fame, who wrote a letter in 1791 to Hendrik Swellengrebel Jr, son of the Cape Colony governor of the same name. Cloete mentions that a hunting party comprising Cape Khoekhoen and European farmers saw an unusual animal:

It had the appearance of a horse; was greyish in colour, and had small white stripes behind the jaw. Sticking out in front of its head was a horn as long as an arm and as thick as an arm at the base. In the middle the horn was flattish but the point was very sharp. It was not fixed to the bones of the forehead but was only attached to the hide of the animal.Footnote 5 … Several burghers [European farmers] and Hottentots say they have seen this animal in Bushmen-drawings on hundreds of rocks and stones. (Schutte Reference Schutte and Böeseken1982, 420)

A 1793 diary entry by a Dutch sea-captain, Cornelius de Jong (Reference de Jong1802, 202), corroborates the sighting of this particular beast and depictions of it in San images. Some years later, in 1824, Carel Hendrik Kruger, a farmer from the eastern Free State Province town of Bethulie, obtained permission to travel outside the Colony in search of potential unicorns he had heard about from some Koranna people (Pellissier Reference Pellissier1956, 210; Voss Reference Voss1979, note 29). In 1851, Galton met the San people in eastern Damaraland (modern-day Namibia) who told him about a gemsbok-like unicorn

whose horn was in the middle of its forehead, and pointed forwards. The spoor of the animal was, they said, like that of a zebra. The horn was in shape like a gemsbok's, but shorter. (Galton Reference Galton1883, 283)

These accounts collectively describe a horse-like animal having one horn pointing forwards, with or without stripes on part of the body, and known to colonists and indigenous communities alike. A key difference between European and San images of unicorns is that, in the latter case, the horns typically point backwards/upwards like the horns of African antelope. From an indigenous perspective, however, such a difference was probably trivial. Indeed, some colonial rock paintings of one-horned animals have a single horn curving forwards or pointing upwards (Fig. 7), suggesting that European unicorn images (perhaps on British badges or in coats of arms) influenced how rock painters at the time thought about the position of the horn. If that happened, we have a remarkable case of Western and San imagery interacting.

Figure 7. Colonial-era rock paintings of one-horned creatures at PRT1 near Indwe, Eastern Cape, exhibiting a possible European influence on the horn's direction. Both examples are associated with a panel of humans in European dress and their livestock. Note the two-dimensional perspective common in such examples. (Photographs: author.)

Indigenous beliefs about unicorns

Lady Barnard's letter mentions that the unicorn was a ‘native god’. At the time, she appears to have thought that the creature was simply a rhinoceros: a pardoned military deserter described to her something ‘much larger than a horse, though less than a small elephant’; he had shoes made of its hide (Wilkins Reference Wilkins1910, 77). The editor of Barnard's letters added a footnote asserting that this ‘must be the rhinoceros’ (Wilkins Reference Wilkins1910, 77). Barrow includes a very similar 1798 letter in his autobiography, which mentions that the writer owned shoes made from unicorn hide, that the animal was fierce and that it was ‘an object of worship to the inhabitants’—details which were probably obtained from the same soldier or social circle (Barrow Reference Barrow1847, 190–91). Rather than ‘the native god’ or ‘something natives worshipped’, these brief, naïve references to local beliefs are likely to indicate, albeit in indigenous idioms which did not survive translation into English, the significance and prominence of the creature in local thought. More is needed, however, to say something about that significance.

Baines was a more sceptical writer. He had searched for rock paintings (proof) of unicorns on farms in the Eastern Cape; hearsay was not enough: ‘The rumours among Hottentots and other tribes bordering on the colony are easily recognised as our own legends of the unicorn, the mermaid, &c., returned to us altered, and perhaps improved, by travel’ (Baines Reference Baines1864, 172). Irrespective of the European tales that made their way into local story-telling traditions, Baines underappreciated how much more complicated the matter was. When he later encountered ‘tales of “eenhoorns” [Cape Dutch: unicorns] having been seen in the Drakensbergs [sic],’ he expressed his reservations: ‘our belief in these vanishes as the localities are explored’ (Wallis Reference Wallis1946, 610–11).

Other early documentary sources report more specific indigenous beliefs. In 1800, the missionary Johannes Theodorus van der Kemp recorded two remarkable sets: one concerning a striped horse-like animal of incredible swiftness known to some Khoekhoen; and one concerning a one-horned creature known to an Nguni group. These descriptions allow us to distinguish two conflated forms: one characterized above all by its single horn and the other by its stripes and resembling a zebra or (now-extinct) quagga. We have already encountered fusions of these characteristics in Barrow's account and others, but they appear not to have mixed invariably in individual animals.

In the first set of beliefs, van der Kemp mentions

an animal, which is not known in the Colony but by the name of the unknown animal. The Hottentots call it kamma. It is sometimes seen among an herd of elks [elands], and is much higher than these. It was never caught nor shot, as it is by its swiftness unapproachable; it has the form of a horse, and is streaked, but finer than the dau [mountain zebra]; its footsteps is [sic] like that of a horse. (London Missionary Society 1804, 461–2, italics in original, bold added; cf. Barrow Reference Barrow1806a (II), 275–7)

This first description partly resonates with some of those given already: though hornless, the creature is fast-moving, horse-like and striped. The animal and the word used to describe it were apparently unknown to van der Kemp. Kamma was probably an Anglicization of an original Khoekhoe word with a click consonant. One possibility is that it is a cognate of ǁkhàmàb, the Khoekhoegowab noun for the red hartebeest (Haacke & Eiseb Reference Haacke and Eiseb2002), a corruption of which was used to designate the red hartebeest subspecies Alcelaphus buselaphus caama (Saint-Hilaire Reference Saint-Hilaire1803, 269; Smithers Reference Smithers1983).

Hartebeest antelope, however, were known in the Colony from at least 1660 ce, as reported in van Riebeeck's Daghregister (Thom Reference Thom1958, 467). This antelope appears to have been known to van der Kemp too. He had earlier diarized, when travelling outside the Colony's eastern border in the vicinity of the Keiskamma River (Fig. 1), that ‘BruntjieFootnote 6 and his companions returned, having shot only four elephants, two elks [elands], and a hartenbeest [sic]’ (London Missionary Society 1804, 406). Moreover, the kamma's horse-like ‘form’, ‘footsteps’ and stripes ‘finer’ than a zebra's do not suggest a hartebeest. Their high shoulders and backward-curving horns are distinct among African antelopes; their spoor (‘footsteps’) are so different from that of equids that they could not reasonably be conflated, and they are not striped (Smithers Reference Smithers1983). The member of van der Kemp's party who later claimed to have seen along the tributaries of the Grootkei River a large horse-like creature among a herd of quaggas is also unlikely to have confused that ‘unknown animal’ for a hartebeest (London Missionary Society 1804, 461–2; cf. Barrow Reference Barrow1806a (II), 275–7).

A more probable translation of kamma comes from a footnote in another of van der Kemp's letters to the Missionary Society: ‘Keis Kamma, is the Hottentot name of the river. It is a compound of T'Kie, sand; and T'Kamma, water’ (London Missionary Society 1804, 400, italics in original). That T'Kamma means ‘water’ agrees with the cognate Khoekhoegowab word ǁgammi (Haacke & Eiseb Reference Haacke and Eiseb2002). Kamma also matches Cape Khoekhoe words for ‘water’ recorded in four eighteenth-century wordlists compiled by the traveller and soldier Robert Jacob Gordon (Fauvelle-Aymar Reference Fauvelle-Aymar2005). Gordon recorded the disyllabic noun for ‘water’ several times, each beginning with a click consonant and ending with ‘-a’. Based on the two different ways that Gordon spelt the word, ćamma and tCamma, François-Xavier Fauvelle-Aymar (Reference Fauvelle-Aymar2005, 175) suggests ‘that the sign Ć corresponds to tC and that both of them are used to mark the click ǁg (Nama orthography)’. The difference between the end vowel of the Khoekhoegowab word (ǁgammi) and that given by van der Kemp (T'Kamma) is, therefore, probably insignificant.

Because water is not an animal, it may initially seem unclear why it offers a better translation of kamma than ‘hartebeest’. There is, however, support from the ǀXam material collected by Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd, which is key to unlocking the reality of the non-real creatures in question. In 1874, one of Bleek and Lloyd's ǀXam informants, ǃKweiten-ta-ǁken, narrated a variant of a story about the rain's or water'sFootnote 7 children (LL.VI.1.3942–3958; Bleek & Lloyd Reference Bleek and Lloyd1911, 198–205; Hewitt [1986] Reference Hewitt2008, 61–6).Footnote 8 Briefly, the tale tells how a girl at the onset of menarche (typically referred to as a ‘new maiden’) is left at the camp while her mother(s) go to collect food. The girl secretly leaves her ritual seclusion hut on several occasions to go to a spring. Each time, she catches, cooks and eats ‘water children’, thereby breaking food taboos associated with the menarcheal rite. This transgressive act angers the Rain (the ‘water adult’), who punishes the girl and her family by turning them into frogs and reverting their belongings into the materials from which they were made.

In telling the tale, ǃKweiten-ta-ǁken described the water as a striped horse-like animal similar to van der Kemp's kamma. In a note attached to the phrase !kwā kă !káukǝn,Footnote 9 meaning ‘the water's children’ (LL.VI.1.3942), Lloyd noted that ǃKweiten-ta-ǁken

has not seen these things, but she heard that they were beautiful, and striped like a ǀhabba.Footnote 10 The [adult] water was great, as a bull, and the water's children were as cow's children (the size of the latter), being the children of great things. (LL.VI.1.3941')

Significantly, the water and its children are non-real rather than biological animals. Although neither van der Kemp's Khoekhoe informants nor ǃKweiten-ta-ǁken mentions horns, the creatures they describe resemble rain-animals, well-known in San ethnography and rock art (Lewis-Williams Reference Lewis-Williams1981, 103–6; Lewis-Williams & Challis Reference Lewis-Williams and Challis2011; Lewis-Williams & Dowson [1989] Reference Lewis-Williams and Dowson1999, 92–9; Lewis-Williams & Pearce Reference Lewis-Williams and Pearce2004a; Reference Lewis-Williams and Pearce2004b, 141). Their accounts go some way to explaining why unicorns in colonial reports are striped horse-like animals. Although stripes are not typical of European unicorns, they are associated with the rain in San thought: ǀXam girls at menarche would paint ‘zebra stripes’ on young men with red haematite to protect them from ǃKhwa:'s [the Rain's] lightning (LL.VI.1.3972'–3973; Hollmann Reference Hollmann2004, 131).

Though ‘zebra stripes’ and ‘unicorn horns’ are associated with the same animal in some sources, the two appear to have been distinct. This point brings us to van der Kemp's second set of beliefs. He recorded that ‘the Imbo’

say that there is behind their country a very savage animal, of which they are much afraid, as it sometimes overthrows their kraals, and destroys their houses. It has a single horn placed on his forehead, which is very long; it is distinct from the rhinoceros, with which they are also well acquainted. (London Missionary Society 1804, 463)

Some uncertainty surrounds the identity of ‘the Imbo’. The pre-Mfecane (c. 1815) date of van der Kemp's report means that he must be referring to part of the abaMbo group of southeastern Nguni peoples rather than later Mfengu groups (Bryant [1948] Reference Bryant1970, 17–18; Hammond-Tooke Reference Hammond-Tooke1965, 145; Reference Hammond-Tooke1968, 28, 42; Soga Reference Soga1927; van Warmelo Reference van Warmelo1935, 60; Wilson Reference Wilson1959, 171–2; cf. Ayliff & Whiteside Reference Ayliff and Whiteside1912). The colonial, ethnicized form of eMbo, meaning ‘in the country of the Mbo’, was used by shipwreck survivors and inhabitants of what is now the Eastern Cape to refer to inhabitants of what is today southern KwaZulu-Natal (John Wright pers. comm., 21 March 2021). eMbo means ‘east’ relative to eNguni, ‘west’ (Jeff Peires pers. comm., 29 March 2021). ‘Imbo’ can thus be understood as meaning ‘people to our east, speaking the same kind of language as we do’ (Jeff Peires pers. comm., 29 March 2021; see also Lichtenstein Reference Lichtenstein and Plumptre1812, 298; Peires Reference Peires1981, 97; Wilson & Thompson Reference Wilson and Thompson1982, 129–30).

‘Imbo’ country was in the interior of the Eastern Cape between the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg Escarpment and the southeastern coastline of South Africa (Edinburgh Missionary Society 1801, 82; cf. London Missionary Society 1804, 411, 463). ‘Behind’ that country may mean away from the coastline and toward the interior, situating the ‘very savage animal’ toward the mountains of the Maloti-Drakensberg inhabited, albeit not exclusively, by the ‘Abbatoana’ San groups thought by colonists and locals alike to be the painters of unicorn images (Ellenberger & Macgregor Reference Ellenberger and Macgregor1912, 1–14; London Missionary Society 1804, 435; Stow Reference Stow1905). But van der Kemp's own southwest-to-northeast presentation of different groups in that part of the country suggests that ‘behind’ is more likely to mean further to the northeast, not inland. To my knowledge, one-horned creatures are not reported in anthropological and ethnographic studies of Nguni groups despite the pre-Mfecane settlement of several well-known groups such as amaMpondo, amaMpondomise, amaBomvana and amaXesibe in the Eastern Cape (e.g. Wilson & Thompson Reference Wilson and Thompson1982). Though it would be erroneous to assert that unicorns in South Africa were exclusive to San groups, it is likely that they originated in San, or perhaps Khoesan, cosmology.

Apart from Barrow (Reference Barrow1801, 303), only one other account locates unicorns in the western rather than eastern parts of the Maloti-Drakensberg region. In 1826, the Prussian naturalist Ludwig Krebs wrote to the German traveller and zoologist Hinrich Lichtenstein that some amaTembu had told him ‘of a unicorn, of which three were to have stayed for some days on a high mountain, a few days’ journey this side … and they said it was terribly wild’ (ffolliott & Liversidge Reference ffolliott and Liversidge1971, 60; see also Phillips Reference Phillips1827; Voss Reference Voss1979, 13). Whether Krebs's ‘terribly wild’ and van der Kemp's ‘very savage’ are synonymous is an unknown but intriguing possibility.

By contrast, three 1803 sources support the location of the unicorn somewhere to the northeast of lands settled by amaXhosa-speaking groups, including amaTembu (Peires Reference Peires1981; Wilson & Thompson Reference Wilson and Thompson1982, 77). In that year, the Governor of the Cape, General Jan Willem Janssens, journeyed into the country's interior on a diplomatic peace-making mission (Schoeman Reference Schoeman1933, 68). He was accompanied by his aide-de-camp Willem Bartholomé Eduard Paravicini di Capelli and Dirk Gysbert van Reenan, a prominent farmer and son of Jacob van Reenen, who led the search for survivors of the Grosvenor wreck (Carter & van Reenen Reference Carter and van Reenen1927). Janssens also asked Coenraad de Buys, a remarkable character who lived for some time beyond the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony (Schoeman Reference Schoeman1933), to assist him in his efforts. Both the official record and Paravicini di Capelli's diary report that the party searched for rock paintings of unicorns unsuccessfully but were assured by colonists that paintings were to be found; de Buys asserted that such an animal existed (Paravicini di Capelli Reference Paravicini di Capelli and de Kock1965, 145–6, 252; see also Godée Molsbergen Reference Godée Molsbergen1932, 174; Voss Reference Voss1979, 7–8). Van Reenan's diary, however, contains details absent from the other two accounts:

Buys also told us that to the north of the Tambookies [amaTembu] there lives a yellow people with long hair, named Matola [amaTolo], and the unicorn is to be found there, of the size of an eland, and black in colour. (Voss Reference Voss1979, 8; cf. Blommaert & Wiid Reference Blommaert, Wiid, Franken and Murray1937, 167)

Significantly, this report corroborates van der Kemp's Imbo informants and the specific reading of ‘behind Imbo country’ as meaning ‘to the northeast’. The amaToloFootnote 11 were an Nguni group who, before the Mfecane, lived at the eastern edge of the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg Escarpment around Giant's Castle in the KwaZulu-Natal Province—far to the northeast (rather than directly north) of amaXhosa and amaTembu territories (Challis Reference Challis2008, 115ff). Importantly, the amaTolo had close ties with San groups who lived along the southern parts of the Escarpment (Challis Reference Challis2008, 122–3).

The location of unicorns (distinct from rhinoceroses) in the eastern parts of the Maloti-Drakensberg region is broadly corroborated by the French missionaries Thomas Arbousset and François Daumas (Reference Arbousset, Daumas and Croumbie Brown1846, 133) as well as by an 1860 report of a public meeting in the Colony of Natal (de Kok Reference de Kok1904, 199–202). The 1860 report records that both amaZulu and Basotho informants described to their colonial employers fierce, one-horned creatures inhabiting the mountains where the San and Basotho lived.

The eminent South African anthropologist Monica Wilson (née Hunter) provides still further, though more recent, support for the location of ‘unicorns’ in the northeastern parts of the Maloti-Drakensberg. She points out that, among amaMpondo, an ‘appeal to outsiders was a usual principle in rain-making’ (Hunter [1936] Reference Hunter1961, 84). This applied typically to amaYalo rainmakers (unrelated to the royal house) and, more recently, to Christians (Hunter [1936] Reference Hunter1961, 80, 84). Wilson notes that

The amaYalo are great rain and lightning doctors, and people of other clans sometimes shout to the storm to go to them. ‘Go! Pass! Go north (storms travel south-west to north-east) to the amaYalo of Tyone! (a Yalo chief). There old beer is drunk. Go to your own people.’ Or ‘Go! Pass north to the place of the Yalo!’. (Hunter [1936] Reference Hunter1961, 299, parentheses in original)

The natural and physical direction in which rainstorms travel in the Eastern Cape and the location of powerful rainmakers in the same direction are significant. Van der Kemp's Imbo informants located the animal to the northeast because rain travels in that direction and because the powerful people who controlled it lay in that direction too. In this regard, it is significant that the destruction of Imbo kraals and houses by ‘a very savage’ one-horned animal ‘distinct from the rhinoceros’ (London Missionary Society 1804, 463) readily resembles the behaviour of male rains (thunderstorms) in San belief, which destroy huts and camps (Bleek 1933a, 299, 308–9; Marshall Reference Marshall1957b, 232; Reference Marshall1999, 164; see also Valiente-Noailles Reference Valiente-Noailles1993, 196). This parallel suggests that it was local, rain-controlling San who lay in the direction of the rain's travel.

There are several parallels between Nguni and San rituals and beliefs concerning rain (Hunter [1936] Reference Hunter1961; see also Dowson Reference Dowson, Chippindale and Taçon1998; Schoeman Reference Schoeman2006, 48ff; Whitelaw Reference Whitelaw2017). For example, and though San (e.g. Lewis-Williams Reference Lewis-Williams1981, 103–16) and amaMpondo (Hunter [1936] Reference Hunter1961, 80–81, 83) rainmaking ritual practices and beliefs differ in several ways, amaMpondo interviewed by Wilson explained that disrespecting the rain broke one of several taboos which could result in the failure of a rainmaking ceremony (Hunter [1936] Reference Hunter1961, 82). Notably, anything ‘that lightning has struck is both dangerous in itself and liable to be used by a sorcerer [iqhira] to harm people’ (Hunter [1936] Reference Hunter1961, 301). Indeed, the lightning produced during thunderous rainstorms frequently destroyed amaMpondo houses and livestock (Hunter [1936] Reference Hunter1961, 301, 302–3), which resonates strongly with van der Kemp's report (London Missionary Society 1804, 463).

Details in de Buys's account point to further parallels with San thought. He described the unicorn as ‘of the size of an eland, and black in colour’. It is well-known that, for the San, the eland is associated with the rain; indeed, it is one form of the rain (LL.VIII.16. 7461–7462; LL.VIII.17.7463–7472; Lewis-Williams Reference Lewis-Williams1981). The colour black is also significant. Among the ǀXam, ‘black’ and ‘rain’ are associated in black rainclouds (Bleek Reference Bleek1932, 339–41; Reference Bleek1933, 310–11). Black livestock animals, especially fat ones, are associated with rain practices among isiNtu-speaking agro-pastoralists (Hammond-Tooke Reference Hammond-Tooke1998; Hunter [1936] Reference Hunter1961; Schoeman Reference Schoeman2006, 48ff; Whitelaw Reference Whitelaw2017; see also Dowson Reference Dowson, Chippindale and Taçon1998). It is well known that San ritual specialists made rain for amaMpondomise and received livestock for their rainmaking services (Callaway Reference Callaway1919, 49; Gibson Reference Gibson1891, 34; Hook Reference Hook1908, 327; Jolly Reference Jolly1986, 6; Reference Jolly1992; Prins Reference Prins1990; Scully Reference Scully1913, 288).

The South African ‘unicorn’ thus appears to be a manifestation of the rain, another form of San rain-animals. Though van der Kemp's Khoekhoe informants and ǃKweiten-ta-ǁken give some indication that striped horse-like creatures are water/rain, the strongest evidence for the same being true of ‘unicorns’ comes from another passage in the Bleek and Lloyd Archive. When ǀHanǂkass'o, one of Bleek and Lloyd's other teachers, narrated his longer, more detailed version of the waterchildren story—the same story told by ǃKweiten-ta-ǁken—to Lloyd on 18 September 1878 (LL.VIII.17.7473–7519; Guenther Reference Guenther1989, 106–9; Hewitt [1986] Reference Hewitt2008, 61–6), he referred to a one-horned rain-animal. ǀHanǂkass'o's mention of a one-horned creature was no coincidence: most ǀXam narratives about horned rain-animals describe them as bull-like creatures with two horns (Lewis-Williams Reference Lewis-Williams1981, 103–6; Lewis-Williams & Challis Reference Lewis-Williams and Challis2011; Lewis-Williams & Dowson [1989] Reference Lewis-Williams and Dowson1999, 92–9; Lewis-Williams & Pearce Reference Lewis-Williams and Pearce2004a; Reference Lewis-Williams and Pearce2004b, 141).

Toward the end of ǀHanǂkass'o's tale, when the girl goes to kill one of the water's children for the last time, he said that

[t]he waterchild did not come out quickly because it was a grown-up water. She [the girl] made ripples in the water, for the waterchild would not come out soon, because a horned Rain-child he was. And the waterchild's horn poked out. (LL.VIII.17.7512–7513, emphases added)

ǀHanǂkass'o made it clear that the girl killed only one waterchild (!khoā-ʘpu̥ắ-kǝn) on each occasion. !khoā-ʘpu̥ắ-kǝn is a singular compound noun formed from !khwa:, ‘rain’ or ‘water’ (Bleek Reference Bleek1956, 427), and ʘpwa, one of the nouns for ‘child’ (Bleek Reference Bleek1956, 684). The suffix (-kǝn) denotes the emphatic nominative case of the noun (Bleek Reference Bleek1928/29, 87–8; Hollmann Reference Hollmann2004, 395–6). The last waterchild in the narrative was, however, notably distinct from all the others that the girl had killed because it was ‘grown-up’ (kki ya, an alternative spelling of kiki:ta: Bleek Reference Bleek1956, 92–3). Indeed, its status as a ‘grown-up water’ is indicated by the fact that it was horned (ǁkẽja). The sentence containing the word ‘ǁkẽja’ for horned is given as an example under the entry for ǁkẽ or ǁkeĩ ([tooth or horn] in A Bushman dictionary (Bleek Reference Bleek1956, 567). Though the English translation of the full sentence in the Dictionary differs slightly from that in the manuscript,Footnote 12 Lloyd's original translation of ǁkẽja as ‘horned’ was maintained.

That the waterchild had one horn only, not merely one of a pair, is confirmed by ǀHanǂkass'o's use of the singular noun ǁkeĩ. The Dictionary indicates in separate entries that ǁkeĩ is a word found in both SI (ǀXam) and related SII San languages. The entries for the SI forms of ‘horn’ are clear, even though the Dictionary also gives the same word for horn in SII, and translates it and another form, ǁkeĩƞsa, in the plural (Bleek Reference Bleek1956, 568). The Dictionary gives one entry for the singular SI form, ǁkeĩ (horn: Bleek Reference Bleek1956, 567), and a separate entry for the reduplicative plural, ǁkeĩǁkeĩ (horns: Bleek Reference Bleek1956, 569). Although some ǀXam nouns do not have different plural forms (Bleek Reference Bleek1928/29, 92; Hollmann Reference Hollmann2004, 400), the reduplicative plural in the Dictionary suggests that ǁkeĩ is not such a noun and is indeed singular. Lloyd's original translation of the word thus appears correct. ǀHanǂkass'o's reference to a ‘grown up’ waterchild with a single horn is therefore unambiguous and constitutes, contra Knox-Shaw (Reference Knox-Shaw1997, 20), the only recorded description of the exact words that a San person used to refer to such a creature.

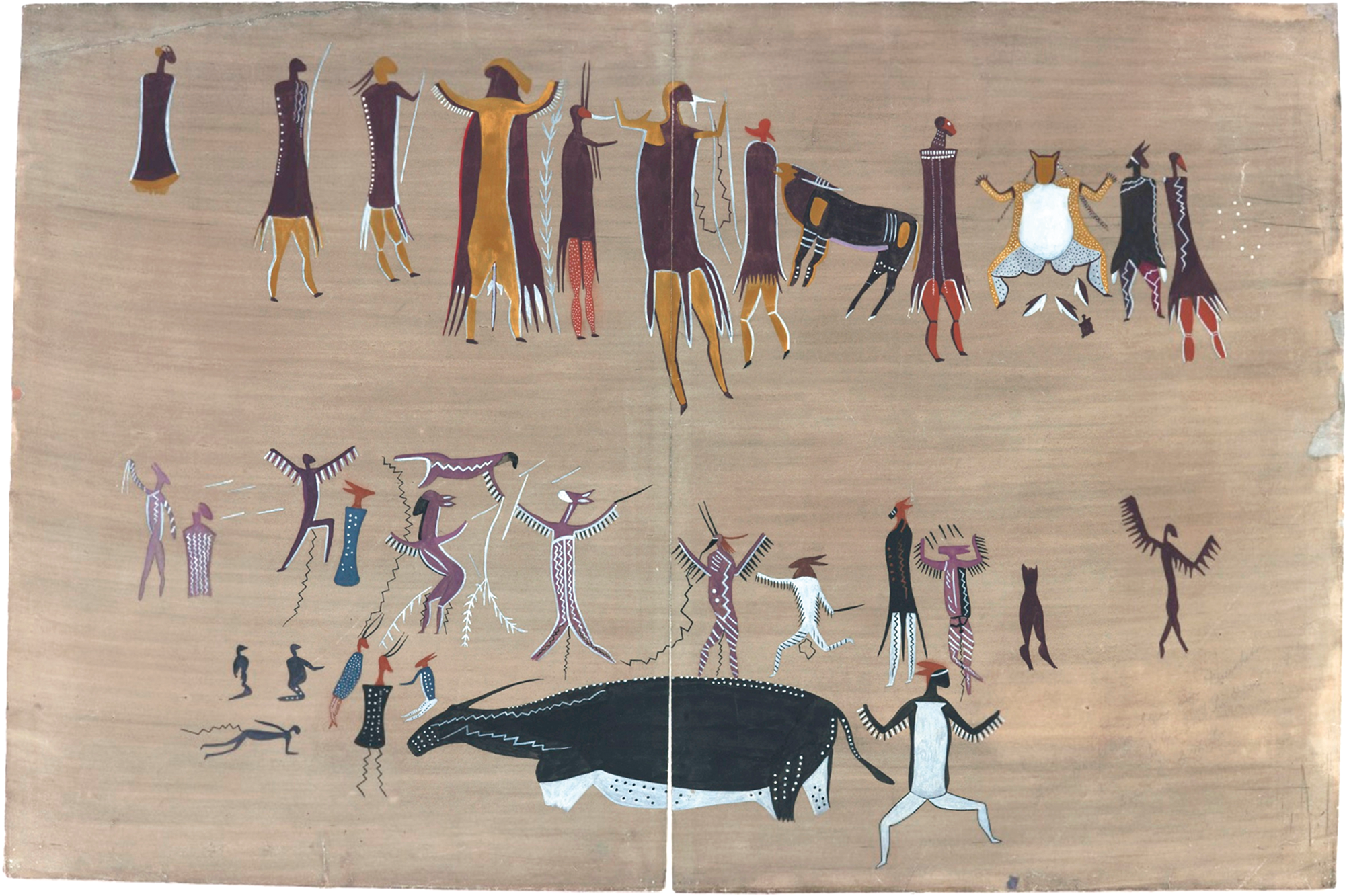

Remarkably, ǀHanǂkass'o's description of a one-horned rain-animal is implicated in commentary from an unnamed ǀXam informant on Stow's copy of rock paintings from a site in the Free State (Fig. 8). The commentary, published by Dorothea Bleek, concerns the Rain's punishment of a misbehaving girl at menarche.

Figure 8. Stow's plate 58. Note the one-horned black rain-animal in the bottom row. Published in Stow & Bleek (Reference Stow and Bleek1930). (© Iziko Museums of Cape Town, Social History Collections, South Africa: www.sarada.co.za)

The informant identified the leopard-spotted figure in the top right corner as a

‘Frog. Thought to be a girl who ate what she should not and was changed into a frog. Her people go to her. The rain is below, a black rain. It has killed the people. The girl ate touken, she displeased it. The arrows become reeds and stay at the spring, the sticks become bushes at the spring (house sticks I believe).’ This is an allusion to ‘The Girl's Story’ in Specimens of Bushman Folklore. See Plate 45. (Stow & Bleek Reference Stow and Bleek1930, description of plate 58)

Although the informant was presented with an apparently coherent picture, the copy was Stow's artefact.Footnote 13 Sven Ouzman's tracing of the original in the archives of South Africa's National Museum in Bloemfontein shows no dots on the body of the ‘frog’ or the fish and turtle beneath it. Whether Stow added them in or they are simply no longer visible, the informant seems to have associated the leopard-spotted figure in the top row with the ‘black rain’ in the bottom row, and, consequently, identified it as a frog. While frogs are common in ǀXam rain myths (see Thorp Reference Thorp2015 for a summary), images of frogs are exceedingly rare in South African rock paintings (Lewis-Williams & Challis Reference Lewis-Williams and Challis2011, 161; see also Thorp Reference Thorp2013, 251; Witelson Reference Witelson2018).

The same commenter's identification of the large black and white animal in Stow's copy as ‘a black rain’ is more reliable. Like ǀHanǂkass'o, the commenter appears to have been familiar with one-horned rains and recognized one in Stow's copy. Though Stow reproduced the animal in black and white, it was originally painted predominantly in dark red. Nevertheless, the colour comment is important: we have already seen that, in ǀXam thought, black is associated with storm clouds (Bleek Reference Bleek1932: 339–41; Reference Bleek1933, 310–11), and that black is also associated with Nguni rainmaking practices and San rainmaking services. Moreover, this ‘black rain’ matches de Buys's description of the ‘unicorn’ as ‘of the size of an eland, and black in colour’ (Voss Reference Voss1979, 8).

I now turn to a second key detail in the ǀXam commentary on Stow's copy. The commenter linked the painted group to ǀXam narratives about disobedient ‘new maidens’ being punished by ǃKhwa:—specifically the waterchildren variants of these tales rather than other versions. We can, therefore, directly link this commentary to the fuller narratives and compare them. The commenter said that ‘the girl ate touken’. This noun does not appear in the Dictionary (Bleek Reference Bleek1956). The word does, however, appear in a ǀXam comment on another of Stow's copies, the infamous line of dancing frogs (plate 45):Footnote 14 ‘The water is destroying these people, changing them into frogs, because a girl had been eating touken, a ground food’ (Stow & Bleek Reference Stow and Bleek1930, explanation for plate 45, emphasis added). As I show, however, either when Dorothea Bleek published Stow's copies or sometime before, ‘touken’ was mistranslated, and, consequently, its significance has gone unrealized ever since (e.g. Lewis-Williams & Challis Reference Lewis-Williams and Challis2011, 160–64).

We can be sure that ‘touken’ is actually the ǀXam word !aukǝn or !kaukǝn, meaning ‘children’ (Bleek Reference Bleek1956, 372). The original ǀXam word is related to ʘpwa, one of the single nouns for ‘child’ (Bleek Reference Bleek1956, 684) that ǀHanǂkass'o used in his waterchildren narrative. Crucially, the singular ʘpwa [child] changes form in the plural and becomes !kaukǝn (children: Bleek Reference Bleek1956, 372, 684). Thus toi ʘwa [ostrich child] becomes toi-ta !kaukǝn [children of ostrich], and !khwa:-ʘpwa [water child] becomes ǃkhwa:-ka !kaukǝn [children of water]. Whereas ǀHanǂkass'o used the singular form (LL.VIII.17.7473–7519), ǃKweiten-ta-ǁken used the plural (LL.VI.1.3942–3958).

Together with Stow's copy, the correct translation of ‘touken’ as ‘children’ provides a direct link between narratives about one-horned rain-animals and depictions of them (not the narratives) in rock art. In Stow's copy, the ǀXam commentary suggests that the ‘black rain’ is the Rain (ǃKhwa:) himself. We have, therefore, direct and further confirmation that the one-horned antelope is a form of the rain, in addition to the other known forms. This form may not, however, have been limited to rains. It was said that the southeast wind ‘lies on the wind's horn’ (LL.VIII.13.7196'; Bleek Reference Bleek1932, 337, emphasis added). Although no further information was recorded, it is difficult not to suggest that this is a conceptually related description.

Inasmuch as the South African unicorn is frequently described as being one-horned and horse-like, it is notable that some Juǀ'hoansi San, who live in the Kalahari Desert far to the northwest of the Maloti-Drakensberg, refer to rain-bringing clouds as ‘“horses” (ǀdwesi) because, although a person may think the cloud is far away, it comes as swift as a horse runs and is suddenly upon him’ (Marshall Reference Marshall1999, 164). From a San perspective, then, there is at least one parallel between the behaviour of horses and that of rains. This parallel, however, is not isolated. Juǀ'hoan rain rites involve single-horn containers for ‘rain medicine’ (Blackwell & d'Errico Reference Blackwell and d'Errico2021, figs 12.25–12.29, 13.5; Marshall Reference Marshall1999, 166). Unpublished material obtained from Juǀ'hoansi interlocutors by David Lewis-Williams with Megan Biesele acting as translator records remarkable details about how such artefacts were used. Some nǀomkxaosi (owners-of-potency)

also ‘commanded the rain.’ After the lightning had struck a tree, the rain medicine men searched near roots for the ‘rain's teeth’ [fulgurites]. These were dug up and ground up with the red bark of a certain tree. Then they killed a steenbok and placed the medicine in the horn. The horn was then attached to their hair. When they wanted to calm a male rain [thunderstorm] they blew on the horns and stuck them on their foreheads. [Lewis-Williams, unpublished fieldnotes]

Similarly, in nineteenth-century South Africa, stock raiders with San members called down rain ‘by blowing a blast on an eland horn’ to hide themselves from the pursuing colonists (Vinnicombe Reference Vinnicombe1976, 52). Collectively, these details point to a geographically widespread and potentially ancient stratum of San rain-influencing practices (Witelson Reference Witelson2022, 260ff). This possibility is especially intriguing in light of Sigrid Schmidt's (Reference Schmidt1979) suggestion that the antelope-like (rather than serpentine or cattle-like) form of rain-animals is the original, pre-contact form of the rain among autochthonous southern African hunter-gatherers.

The truth will out

The story of the South African unicorn is a remarkable example of the extent to which at least some parts of distinct colliding cultural worlds may intersect during cross-cultural interactions. While colonial collisions were typically and in most respects catastrophic, the strong, superficial resemblance of one-horned rain-animals to European unicorns resulted in a complicated conflation of ideas. In this regard, is notable that the search for the unicorn in South Africa is an early precursor of the colonial science that later emerged in the Cape Colony in the mid nineteenth century (Dubow Reference Dubow2004): while unicorns and the indigenous inhabitants of southern Africa could be accommodated in European natural history, local customs and beliefs had no such place. Although the conflation of unicorns with San rain-animals may initially seem to be a unique example, it raises the possibility that colonial cross-cultural engagements around the world resulted in still other instances of seamless melds between culturally distinct concepts. Crucially, however, such melds would, almost by definition, be virtually invisible from our position in the present. Acknowledgement of their existence requires, almost necessarily, a new historical analysis, and interrogation, of our conventional views.

Acknowledgements

I thank Ben Maclennan and the Anderson Museum in Dordrecht (Eastern Cape) for taking me to visit rock art sites around the Stormberg, and bringing the images shown in Figures 5 and 7 to my attention. I thank Stephen Townley Bassett for permission to reproduce his photograph. I thank Iziko Museums of Cape Town, Social History Collections and www.sarada.co.za for permission to reproduce Stow's copy. I thank John Wright and Jeff Peires for improving my understanding of ‘the Imbo’. David Pearce and David Lewis-Williams commented on earlier versions of the paper. The research for this article was made possible by Susan Ward and a doctoral internship grant from the University of the Witwatersrand's Science Faculty Research Council.