Maya ontology is one where few binary distinctions are drawn between the animate and inanimate. Caves, for example, are extensions of earth's hollow interior and places populated by gods and ancestral souls; however, caves are not strongly distinguished from constructed features, such as temple shrines or sweat baths (e.g. Prufer & Kindon Reference Prufer, Kindon, Prufer and Brady2005; Pugh Reference Pugh, Prufer and Brady2005; Vogt & Stuart Reference Vogt and Stuart2005). Both locations, as Brown and Emery (Reference Brown and Emery2008, 300) argue, ‘mark important thresholds where human and non-human actors interact’. Offerings presented to these and other sacred locations are a means of ceremonial negotiation intended to produce tangible outcomes and real change in the world. The choice of proffered materials as well as the structure and timing of the offering are, therefore, evidence of a ritual discourse. Breaking, smashing, burning, cutting and suffocating, among other destructive actions, effectively release the animate and vital matter from their intact form. Referred to as ch'ulel by the Tzotzil and k'uh by the Classic and Postclassic period Maya (c. ad 500–1500; Table 1), the vitalizing essence animating the world, as Houston (Reference Houston2014, 83) explains, can be ‘segmented into beings with personality and predispositions [that adhere] to particular objects, places, effigies, even units of time’. This essence, however, cannot be created; it can only be transformed or transferred from an existing animate substance. Embedded in Classic Maya ritual practice was a material-mediated negotiation whereby sacrificed bodies, beings and objects were the means of directing essence elsewhere. Material accumulations resulting from these negotiations offer an opportunity to evaluate emic perceptions of the specific needs and demands of a particular context, event, or animate place.

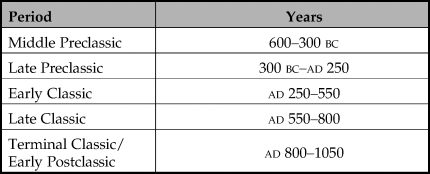

Table 1. Mesoamerican chronological periods for Xultun.

Within Maya archaeology, typological categories are used to define excavated ritual deposits. Small, intrusive deposits placed within constructed features, for example, are defined as caches, and also interpreted as offerings that fed or renewed an animate structure or place (e.g. Becker Reference Becker, Iglesias Ponce de León and Ligorred Perramón1993; Chase & Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Houston1998; Coe Reference Coe1959; Reference Coe and Wauchope1965; Pendergast Reference Pendergast and Mock1998). When deposits are larger in scale and found within foundations or later construction episodes, they are instead classified as a dedication or termination deposit. While a dedication ritual is interpreted as a way of imbuing a new construction with an animate soul (Brown & Garber Reference Brown, Garber, Brown and Stanton2003, 92–3), termination rituals, on the other hand, are perceived as the means of releasing or killing a structure's soul (Freidel & Schele Reference Freidel, Schele, Schele, Hanks and Rice1989; Mock Reference Mock1998; Stanton et al. Reference Stanton, Brown and Pagliaro2008). These deposits are, however, found in similar locations, making them difficult to distinguish, save for occasional contextual clues. Similar issues are noted for the so-called problematical deposit (Iglesias Ponce de León Reference Iglesias Ponce de León1988, 27). Frequently comprised of large volumes of midden-like materials recovered in final occupation levels, these deposits are common phenomena formed prior to site abandonment (Clayton et al. Reference Clayton, Driver and Kosakowsky2005; Houk Reference Houk and Houk2000; Newman Reference Newman2019) or as a result of post-abandonment pilgrimages (Navarro-Farr Reference Navarro-Farr2009). Materials range from shell ornaments, pottery sherds, partial or sometimes whole vessels, to animals and even occasionally human bones. Frequently burned, broken and scattered, these items were intentionally selected, often acted upon and then integrated into a larger offering with a specific aim. Extending from human beings to utilitarian goods, the animate world of the Classic Maya included an intricate network of relations that existed among diverse social actors.

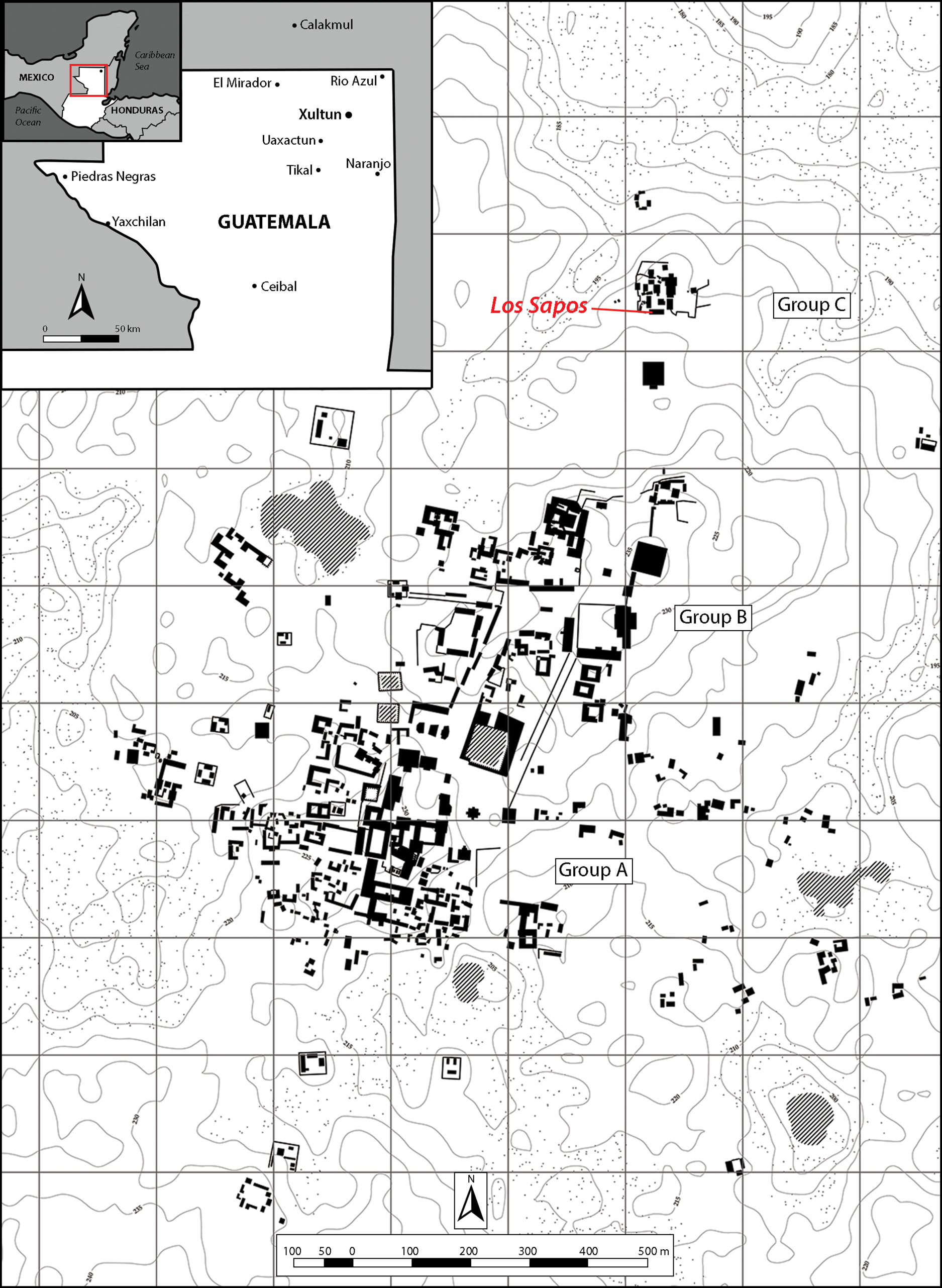

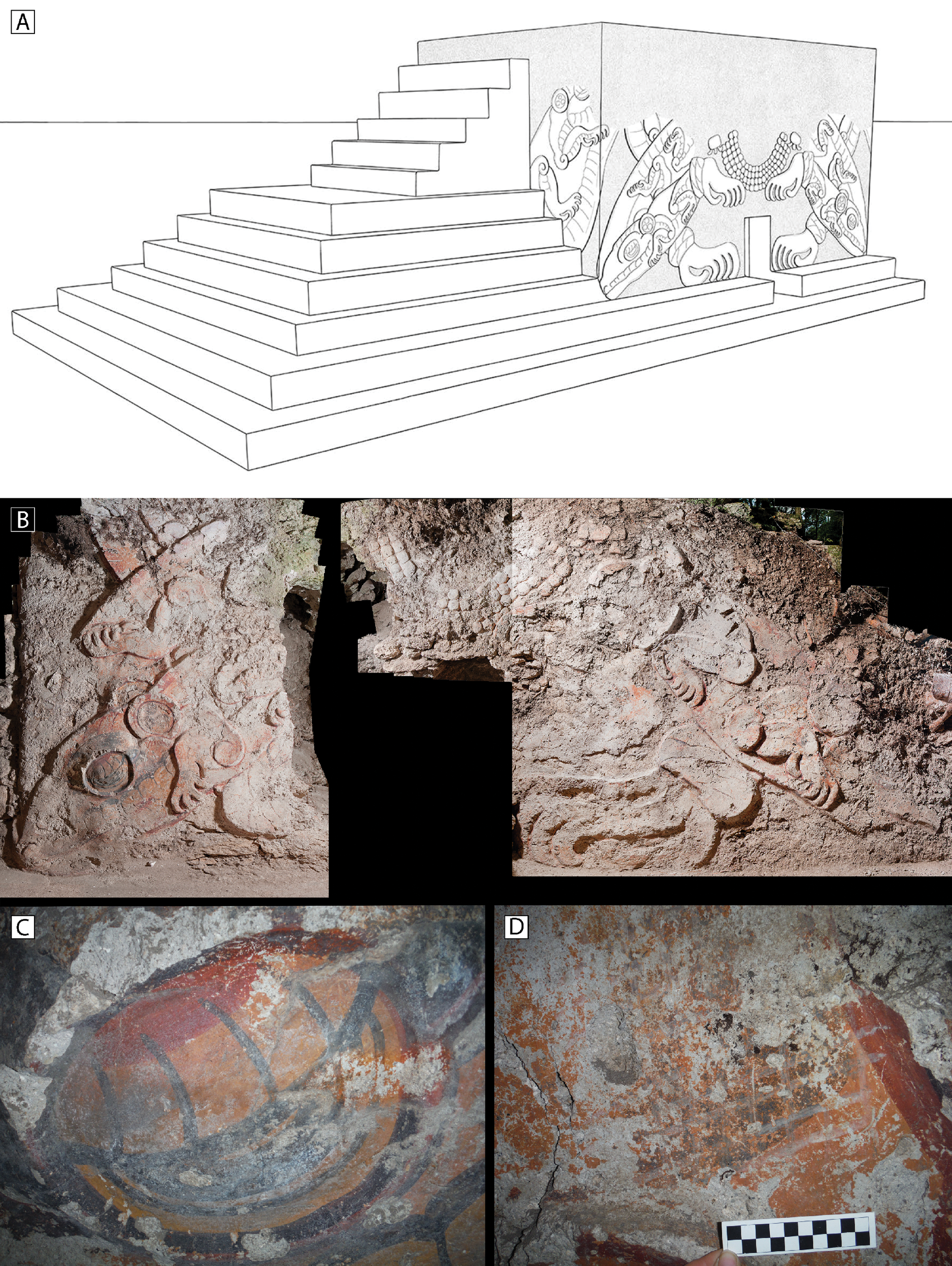

In this article, we present an analysis of one particular deposit recovered at the Classic Maya site of Xultun, Guatemala (Fig. 1). In addition to analysing its structure and assembly, we include an evaluation of the relationships indicated by the contents and the context of the offering. This approach draws inspiration from the ontological turn in archaeology (e.g. Alberti & Bray Reference Alberti and Bray2009; Alberti & Marshall Reference Alberti and Marshall2009; Henare et al. Reference Henare, Holbraad and Wastell2007), which incorporates indigenous ontologies into archaeological interpretive frameworks. As Harrison-Buck (Reference Harrison-Buck2015, 65) explains, recent approaches depart from traditional definitions of animism as a set of beliefs (Tylor [1871] Reference Tylor1993) and instead consider ‘a relational ontology centred on relationships between human and “other-than-human” agents’ (e.g. Haber Reference Haber2009; Harrison-Buck Reference Harrison-Buck2018; Harvey Reference Harvey2006). We consider a problematical deposit as evidence of a ritual discourse between human and non-human social actors, namely individuals from Xultun and a supernatural entity that embodied a particular sweat bath structure. Enveloping the façades of the Xultun sweat bath, Los Sapos, is an individual with limbs composed of iguana/toad conflations positioned so that the doorway is between their legs (Fig. 2). As one entered or exited this sweat bath, one also entered and exited this figure's body, blurring the boundaries between body, being and place (Reference ClarkeClarke in press). Centuries after the personified sweat bath had been entombed, Xultun residents re-entered this context and added a large, complex offering that appears to be an intentional reference to the structure's identity. As there is a considerable history in the negotiations with personified sweat baths in Mesoamerica, we argue that it is possible to evaluate the relationship among offered materials as well as between multiple social actors engaged in this ritual discourse.

Figure 1. The location of Los Sapos at the site of Xultun with the site's global position illustrated within the inset map. (Map of Xultun produced by Carlos Chiriboga, 2016, elaborated by Mary Clarke, 2019.)

Figure 2. The sweat bath, Los Sapos: (A) reconstruction of Los Sapos depicting both preserved façades and the adjoining staircase; (B) composite photograph of Los Sapos north façade (Courtesy of National Geographic Society, 2012); (C, D) detailed photographs of the painted iconography.

Ritual work in an animate world

The distinction between what is sacred and what is profane has shaped archaeological interpretations of past perceptions of the world. Rationalist, Western thought informs us that ceremonial or sacred locations are conscripted or contained, marked off and easily distinguished from the domestic or quotidian sphere of everyday life (Eliade Reference Eliade1959). Similar dichotomies have been suggested for ritual practice. Repetitive and layered with symbolic action, ritual practice, as Durkheim (Reference Durkheim1915) argues, necessarily differed from other performed actions, implying utilitarian practice, not to mention related objects and domestic places, were devoid of symbolic meaning (see Arnal & McCutcheon Reference Arnal and McCutcheon2013 and Brück Reference Brück1999). Scholars engaging with indigenous perspectives of objects, places, and daily life, however, argue that these heuristic tools inappropriately apply western epistemological notions. Specifically, they create divisions between symbolic and utilitarian modes of action where none exist (Alberti & Marshall Reference Alberti and Marshall2009; Bird-David Reference Bird-David1999; Groleau Reference Groleau2009, 398; Hallowell Reference Hallowell1960). This is particularly prevalent in animistic societies (Ingold Reference Ingold2006), such as those of Mesoamerica.

In indigenous Mesoamerican thought, ritual and religion are regarded as work in active terms where faith as well as practice are expressed through actions involving a perceived equivalence. The word meyah or ‘work’ in modern Yukatek Mayan is used, for example, to describe and equate actions such as a shaman's ritual performance, a farmer's act of burning a field and a woman's work of cleaning and sweeping a house (Hanks Reference Hanks1990, 334–5, 364). In Classic period Mayan texts, work in the royal court is likewise equated to that of manual labour, drawing parallels between ‘burdens’ of captive taking and those of cultivating agricultural fields (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006, 225). In a similar manner, ‘ceremony’ is understood in quotidian terms. Among the modern Mixtec community of Nuyoo, Monaghan (Reference Monaghan and Monaghan2000, 32) observed that ‘instead of officiating at a rite, practicing a ritual, or performing a ceremony, officiants are “feeding” or “straightening” or “sweeping”.’ These action-oriented expressions of the Mesoamerican belief system create, as McAnany (Reference McAnany2010, 63) argues, a ritual practice in which ‘ritual performance trumps abstract knowledge of theology, and religious pedagogy emphasizes practical epistemology over ideology.’

Akin to the understanding of faith and performed work, indigenous people of Mesoamerica have not, for the most part, drawn distinctions between the natural and supernatural as is done in Judeo-Christian beliefs. Rather, the supernatural is perceived to dwell within the natural (Monaghan Reference Monaghan and Monaghan2000, 27), creating an animate landscape densely populated by non-human social actors. Features within and certain materials of the natural landscape present opportunities to converse with and otherwise engage supernaturals. This perception of the world is echoed in Mesoamerican cosmogony. In place of an ex nihilo mode of creation, creator deities made or shaped people from the already animate material in the world (e.g. Beliaev & Davletshin Reference Beliaev and Davletshin2014; Christenson Reference Christenson2003, 60; Guiteras Holmes Reference Guiteras Holmes1961, 311; Tedlock Reference Tedlock1996, 215). Although a unified version of these events does not exist, creation is generally understood as a consequence of multiple beginnings, trails, and demises triggered by the confrontations and misdeeds of different gods. In several modern myths from Maya communities, a sequence of three or four eras of creation have been recorded, where former peoples, having offended or slighted the gods, brought about their own demise (Christenson Reference Christenson2003, 66, 70–90; Tedlock Reference Tedlock1996, 66–73). Embedded in these narratives is the notion that the current population is dependent on the continued satiation of the gods, an asymmetrical structure of ‘original debt’ (Earle Reference Earle and Gossen1986, 170) paid through ritual work.

The primary form of debt repayment and ritual work is providing gods with sustenance through prayer, offerings and sacrifice. Underlying these actions is the manner of converting a substance to an essence so that it may be readily consumed by gods (Graulich & Olivier Reference Graulich and Olivier2004, 125). By burning proffered materials, an offering becomes smoke and essence as well as sustenance. Depicted in swirling tendrils of vapour or scent, this essence wafts from smoking braziers as well as other sources, including aromatic flowers, freshly prepared food, and the mouths of individuals (Taube Reference Taube2004). Other sources of divine nourishment are blood (Graulich Reference Graulich2005) and the bodies of humans and animals (Christenson Reference Christenson2003, 235–9; Tedlock Reference Tedlock1996, 164–6). The origin of sacrifice as payment is traced by many Mesoamerican peoples to primaeval covenants with gods and the earth (Monaghan Reference Monaghan1995). According to a K'iche narrative from Cubulco (Shaw Reference Shaw1971, 52–3), the ancestors hurt the earth when they first harvested it. As they were pulled out from the earth, weeds and trees cried out to god, asking for intervention. God reached a settlement between them, where the earth consented to endure the pains of cultivation and provide food and resources for humans so long as humans would feed the earth in return, both with their bodies at death and by satiating its hunger with chocolate, wine, liquor and beer throughout their lifetime.

Failure to perform the ritual work that upheld the covenants had tangible impacts on the lives of the living. The gods would react viciously; they might withhold food and much needed rains (Earle Reference Earle and Gossen1986, 163; Girard Reference Girard1962, 153–4; López Garcia Reference López Garcia2010, 79–121; Wisdom Reference Wisdom1940, 439), allow sickness and prevent recovery (Guiteras Holmes Reference Guiteras Holmes1961), and, as has happened in earlier epochs, instigate a revolt of objects, leaving people at the mercy of their own hostile household goods (Christenson Reference Christenson2003, 70–90; Gossen Reference Gossen2002, 171–3; Tedlock Reference Tedlock1996, 66–73). Demands of exchange or offerings of payment were required in countless contexts. Clearing a forested area to make a milpa [corn field], for example, necessitated negotiation (Thompson Reference Thompson1963, 139), as did house construction. Among the Tzotzil of Zinacantan, Vogt (Reference Vogt1969, 461) documented a ritual referred to as the hol chuch [good heart]. Halfway through the process of building a new house, a hole was dug into its unfinished floor and an offering of blood, smoke and liquor was fed to the earth in exchange for the materials used in its construction. ‘If it is not fed’, according to one Q'eqchi individual (Monaghan Reference Monaghan and Monaghan2000, n. 15), ‘the house will eat you. It wants meat’, likening the house to a jaguar or ferocious beast. Interactions with animate materials and places called on the covenant, expecting exchange and demanding repayment (see McAnany Reference McAnany2010, 70–79). This is particularly true of the Mesoamerican sweat bath.

Personifying the Mesoamerican sweat bath

The traditional Mesoamerican sweat bath is a place for healing and hygiene, one frequently used by midwives in postpartum and perinatal care. However, these places are more than structures: they are relatives, ancestors, and supernatural beings. Chinchilla Mazariegos (Reference Chinchilla Mazariegos2017, 105) notes that among the K'iche’ of Santa Clara la Laguna, Guatemala, ‘the sweat bath is Saint Anne, the mother of Mary, the mythical grandmother who helps healers treat disease and allows midwives to see unborn children inside their mother's womb and fix them if misplaced’. The equivalence of person and place is not unique to this community in western Guatemala. Among the modern Totonac of Puebla, Mexico, Ichon (Reference Ichon1973, 120–22, 151, 297–8) documents the veneration of a group of mothers and grandmothers, the Natsi'itni, who own and preside over the entrance of the sweat bath. Both divine and dangerous, the Natsi'itni demand offerings from the Totonac in order to ensure the life and well-being of newborn infants (Ichon Reference Ichon1973, 333). Negotiations with these animate beings embodied in sweat baths is also found among the modern Otomi of Central Mexico. Galinier (Reference Galinier1990, 152–3; Reference Galinier2004, 61–4) describes post-partum rituals where Otomi mothers must feed the sweat bath offerings of cornbread in order to appease its anger provoked by the presence of blood. The ritual work of negotiating with these structures was not exclusive to mothers and midwives. Among the Mam of Santiago Chimaltenango, Guatemala, Wagley (Reference Wagley1949) explains that the sweat bath where one was first bathed remains an important place as it is also the location where an individual's afterbirth is buried. ‘Each individual should therefore know where his afterbirth was buried’, recounts Wagley (Reference Wagley1949, 23), because ‘one may be sick and the soothsayer's divinations may indicate that the treatment calls for prayers to be offered in front of the sweathouse in which one was “first bathed” and in which the “afterbirth” lives.’ Sweat baths are known as mother or grandmother figures who are both beneficent and pernicious: as such they command attention and are seen as active members of Mesoamerican communities.

The process through which a grandmother figure became synonymous with the sweat bath is reflected in Mesoamerican mythology. Having translated and compared all known accounts of this myth, Chinchilla Mazariegos (Reference Chinchilla Mazariegos2017; Reference Chinchilla Mazariegos, Scherer and Tiesler2018) notes that this goddess is both the grandmother and foe of twin heroes, individuals who, following their defeat of this goddess, go on to create the conditions for human life. The means of this deity's defeat is quite consistent in that she is almost always burned or killed inside the sweat bath, where some myths specifically locate her death within the structure's doorway. One example from the modern Chatino of Tepenixtlahuaca, Oaxaca, Mexico, includes the hero twins stating upon their victory: ‘You will remain here, holy mother, and you will eat from what the children who will be born in the future give you. If they don't feed you, the children will die; everyone will come to you to have strength’ (Bartolomé Reference Bartolomé1984, 11, trans. Chinchilla Mazariegos Reference Chinchilla Mazariegos2017, 110). Once killed or trapped in the sweat bath, the goddess becomes the structure, an understanding that is also evident in ethnohistoric documents from Mesoamerica. In the Nahua Codex Magliabechiano (Nuttall Reference Nuttall1903, f. 77r), the face of the goddess Tlazoteotl is placed directly over the doorway of a sweat bath, making it quite clear that she presided over its entrance (Fig. 3) (Alcina Franch Reference Alcina Franch2000, 215–312). During difficult deliveries documented among the Mexica of the Colonial period, midwives prescribed sweat bath treatments and called out to the goddess Toci (‘our grandmother’) or Temezcalteci (‘grandmother of the sweat bath’) for aid (Sahagún Reference Sahagún, Anderson and Dibble1950–1982, bk 6, 142, 149, 151–60).

Figure 3. The Nahua Codex Magliabecchiano depicting a sweat bath with the goddess Tlazoteotl's face centred above the doorway.

Although these mythological figures vary over the course of Mesoamerican history, they have similar personalities, which Chinchilla Mazariegos aptly summarizes:

[T]he grandmother is at once a primary creator goddess and an aggressive antagonist of the young heroes … her grandchildren, by birth or adoption. Her personality ranges from a nourishing maternal figure to a pathetically lewd old hag and a rancorous child-eater. While not always explicitly identified with the earth, her behavior is consonant with the notion of the earth as a voracious mother who yields her fruits reluctantly and ultimately consumes her children. Overpowered by the heroes, the grandmother acquired an equally duplicitous role as the model midwife—the sweat bath—who delivers children on condition of being properly fed and appeased, but who may also retain them at will. (Chinchilla Mazariegos Reference Chinchilla Mazariegos2017, 128)

The Mesoamerican sweat bath is a place embodied by this duplicitous deity who holds sway over life and death. Failing to perform the ritual work that fed and cared for this being could have disastrous, if not fatal, consequences. Given the severity of this work, the low number of deposits recovered in and around sweat baths is surprising, particularly in Classic Maya contexts. With a total of eight excavated sweat baths, many of which included deposits with several thousand pottery sherds and large frequencies of obsidian, chert, bone, and ground stone materials (Child Reference Child2006; Mason Reference Mason1935; Satterthwaite Reference Satterthwaite1952), the site of Piedras Negras has perhaps the most robust evidence of these negotiations. Due to the inclusion of large amounts of ritually repurposed refuse, these offerings were interpreted as garbage dumps (Child Reference Child2006, 486, 539–40; see also Child & Golden Reference Child, Golden, Stanton and Magnoni2008). By emphasizing relational ontologies over typological categories, we argue that a deposit recovered in front of a sweat bath, Los Sapos, which shares traits with the Piedras Negras sweat bath offerings, is instead a record of a ritual discourse between certain Xultun individuals and a personified sweat bath.

Xultun and the sweat bath, Los Sapos

Located on an elevated karst upland along the southern margin of the Bajo de Azucar in the Petén region of Guatemala, Xultun was an important centre of Lowland Maya civilization (Fig. 1). The first evidence of occupation at Xultun dates to the Middle and Late Preclassic period (c. 600 bc–ad 250; Table 1), with the site reaching its apogee in the Early Classic period (c. ad 250–550) (Urquizú & Pérez Reference Urquizú, Pérez, Hurst and Beltrán2019). During the subsequent years of the Late Classic period (c. ad 550–800), Xultun was a political ally as well as adversary to powerful polities such as Tikal (Houston Reference Houston, Danien and Sharer1992, 66–7), Los Alacranes (Garrison & Stuart Reference Garrison, Stuart, Laporte, Arroyo and Mejía2004, 853), Caracol (Garrison & Stuart Reference Garrison, Stuart, Laporte, Arroyo and Mejía2004, 853) and Motul de San José (Grube & Nahm Reference Grube, Nahm and Kerr1994). It was also actively producing monuments (ad 889) and maintaining its reservoirs (980–1080 cal. ad) well into the Terminal Classic period (c. ad 800–1050). This large, urban centre was organized on a north–south axis, its architecture forming three general groups. The two southern groups, connected by parallel causeways, contain expansive plazas surrounded by numerous stelae, temple pyramids, ballcourts, palatial or administrative complexes and residential groups that extend into the periphery. To the north of these two groups and down a significant slope in the topography is the site's third group. Although this isolated area became a multi-functional residential complex in the Late to Terminal Classic periods (Wildt Reference Wildt2015), architecture dating to the Early Classic period indicates this area was an elaborate, ceremonial centre. Included in this early phase is the sweat bath, Los Sapos.

Within the corpus of Classic period Maya art and architecture, Los Sapos is an outlier. Its rectangular form, with a low, narrow entry in its north façade, is similar to most known sweat baths, as is its firebox located within the structure's steam chamber along its central axis. However, unlike most known sweat baths, Los Sapos emphasized the performed interaction with a central figure depicted on its exterior façades (Fig. 2). Poised in a squatting position, this figure wraps around the steam chamber where the doorway is between the figure's legs. Individuals exiting the structure, therefore, emerged as if (re)birthed from this being's body or contained place, perhaps equating the steam chamber with a hollow, womb-like interior. Use of the structure engaged other body parts as well. Defined by a staircase on the east façade, its back or spine could be scaled, leading from the length of this being's body to the top of the structure. The roof could have functioned as a platform or stage, particularly one that positioned performers on top of the figure's head or perhaps within its mouth. As the Classic Maya at Xultun used this sweat bath, therefore, they also confronted the embodied being.

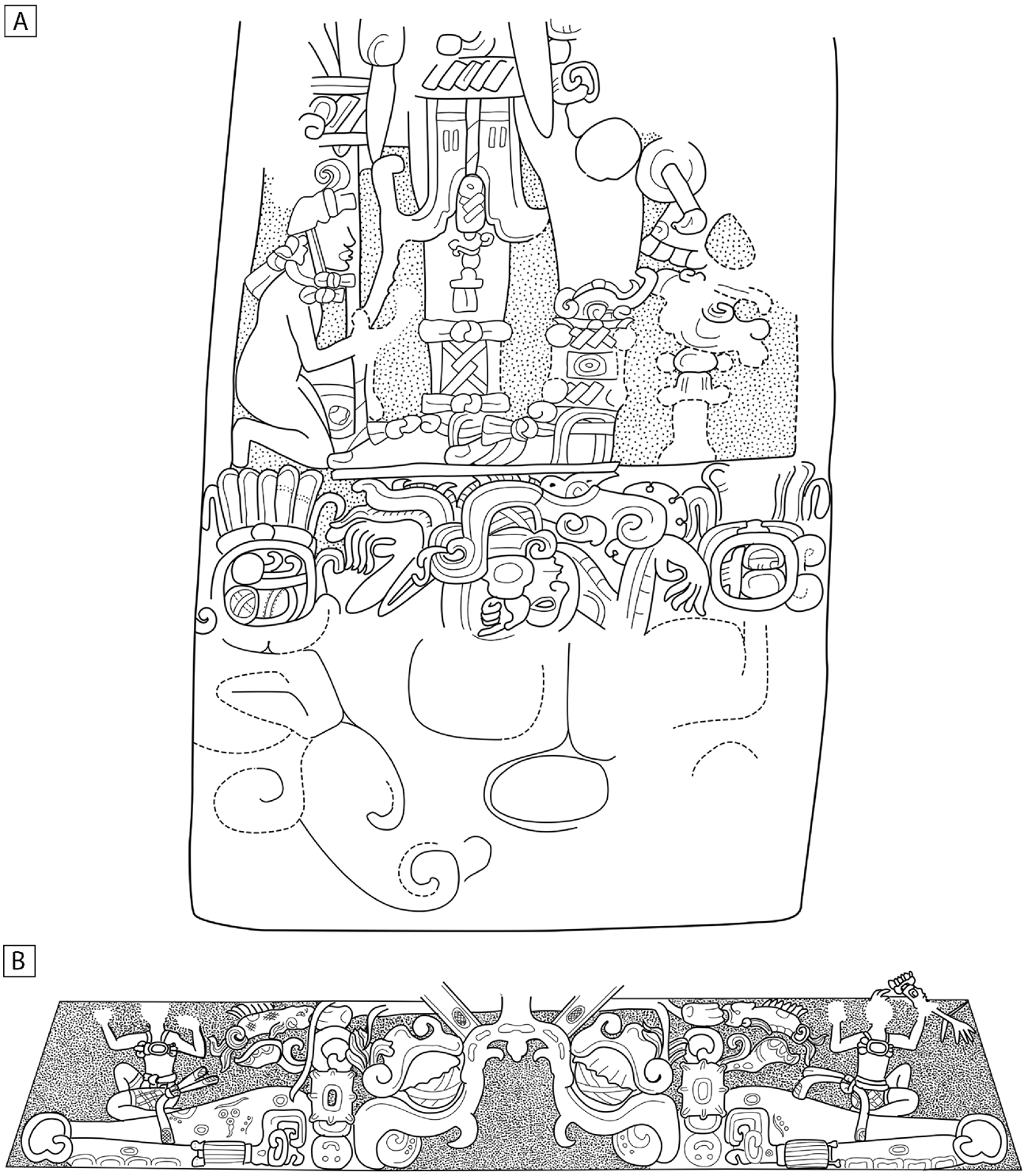

The figure represented at Los Sapos is quite unique, in that there are but a few comparisons within the corpus of Maya art (Clarke Reference Clarkein press). The most iconographically analogous deity from Early and Late Classic period imagery is a female goddess nicknamed the ‘Yaxha Goddess’ (Tokovinine Reference Tokovinine2013, 41). Depicted in her reptilian form on Yaxha Stelae 6, 10 and 13, she floats in an oceanic setting surrounded by anemones, while also functioning as a toponymic register that signifies a specific place (Fig. 4A). Labeled as te'nal yax chan ch'e’n or ‘tree corn [place] the blue-green sky cave’, the location embodied by this deity, as Tokovinine (Reference Tokovinine2013, 41–2) describes, was the blue-green centre of the world. The time-renewal events commemorated and portrayed on the Yaxha monuments, therefore, were performed in this sacred place that was located above or accessed through her mouth. This goddess is also referenced in Classic Mayan texts. Although her name remains undeciphered, Nondédéo and colleagues (Reference Nondédéo, Lacadena, Garay, Kettunen, Vázquez Lopez, Kupprat, Vidal Lorenzo, Munoz Cosme and Iglesias Ponce de Leon2018, 337, n. 3) have proposed a translation of ‘ix.tzutz.sak’. Marc Zender (pers. comm., 2019) tentatively reads her name as ‘the lady who finished (?made) squash seed(s)’ or ‘lady squash-seed-finisher (?maker)’, alluding to an association with germination cycles, particularly their completion. This goddess is also depicted on what Houston (Reference Houston1996) describes as a symbolic sweat bath. Ornamenting the outer sanctuary of Palenque's Temple of the Cross, her head and upper limbs emerge from an oceanic environment (Fig. 4B). Akin to the Yaxha examples, her wide-open mouth acts as an entrance to a sacred place referred to in Palenque inscriptions as Matwil, a watery place of divine origin and ancestral emergence associated with the sea, conch shells and water birds (Stuart Reference Stuart2005, 79, 169). Similar conceptions of place are described throughout Mesoamerica, and it appears that during the Classic period, the Classic Maya anchored it within the body of a reptilian goddess tentatively named ‘ix.tzutz.sak’. It is this figure and embodied place that we argue is represented at Los Sapos.

Figure 4. Representations of the reptilian goddess from the Classic period: (A) Yaxha, Stela 13 (after a field sketch by Ian Graham); (B) the entablature of the symbolic sweat bath, the Temple of the Cross, Palenque, Mexico (after an illustration by Karl Taube).

The offering at Los Sapos

Built in the Early Classic period, Los Sapos was in use as a sweat bath for approximately 250–300 years. The end of its use-life (562–651 cal. ad) was paired with a burial event (Fig. 5). First, an adult individual was interred within a cist tomb extending beyond the structure's doorway. With feet directly in the doorway, this individual was, according to Wildt (Reference Wildt2015), positioned as if being birthed from the structure (Fig. 5B), although see Hannigan (Reference Hannigan, Hurst and Beltrán2019) for a more in-depth analysis of this adult burial. Human interments are frequently recovered in liminal spaces, akin to the Los Sapos doorway (e.g. Ambrosino Reference Ambrosino and Christie2003; Balanzario Reference Balanzario, Nalda and Balanzario2011; Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1994; Haviland Reference Haviland2014, 406–7); however, human burials are rarely found in association with sweat baths (cf. Smith Reference Smith1950, 96). In addition, many of the lower limb elements, particularly the patellar and femoral fragments, show clear evidence of burning (Figs. 5E & 5F). Second, the interior of both the cist tomb and structure were filled in using basket-loads of sediment (Fig. 5C) poured from above, after which Los Sapos was entombed within a subsequent construction phase.

Figure 5. Early to Late Classic period burial located with the doorway of Los Sapos: (A) schematic of the sweat bath; (B) burned bones in situ with the fill context surrounding the remains (Photograph: Jennifer Wildt, 2012); (C) flow patterns visible in the structure's interior fill; (D) recovered skeletal elements (Photograph: David Del Cid, 2019); (E, F) Evidence of burning on distal left femur.

Centuries later, the Classic Maya re-entered the cist tomb (Fig. 6). Radiocarbon dates place this second event within the Late to Terminal Classic period (776–971 cal. ad); however, the inclusion of Pabellon pottery, diagnostic of Xultun's Terminal Classic period (c. ad 850–1050), suggests the later end of this range. Approaching from the west, the Maya removed part of the cist tomb's masonry and the majority of the interred individual's remains. All elements above the distal epiphyses of the femora were removed, leaving behind only those positioned directly within the structure's doorframe. In their place, the Maya built a fire (Fig. 6F) and added a large ritual deposit, which included 1743 ceramic sherds, the remains of a juvenile human, numerous animal bones (n = 521), complete and broken chipped, pecked and ground stone tools (excluding obsidian) and unworked chert flakes (n = 387), among other materials. In the following sections, we present analyses of ceramic materials and both human and faunal remains recovered within what appeared to be a problematical deposit. These analyses aim to identify the treatment and relational position of the assembled materials, and also the particulars of each artifact class, be it a species or iconographic representation.

Figure 6. Details and contextual positioning of materials included in the Los Sapos deposit: (A) schematic of the sweat bath; (B) pottery assemblage; (C) cranium (Photograph: Jennifer Wildt, 2012); (D) postcranial skeleton (Photograph: Jennifer Wildt, 2012); (E) oxidation ring from burning event; (F) burn patterning on the cist-tomb's masonry; (G) north profile of the cist tomb.

Pottery assemblage

The deposit was predominantly of ceramic sherds (n = 1,743) and they were included in all stages of assembly. They have the potential to reflect the locations or multiple sequences of burning as well as the relational difference in artifact treatment, both prior to and during deposition. Ceramic materials were, therefore, reassembled and each of the related sherds were evaluated to determine continuities and differences in their treatment and position. Of the 1,743 sherds, a minimum vessel count of 124 was identified (only including rim sherds), with only 38 of those vessels forming refits (Supplementary Table 1). However, there were also 16 distinct body sections that formed refits, although they did not include a related rim fragment (n = 83 sherds). Body fragments from unslipped vessels were excluded from refit analyses (n = 440), as their similarities make them difficult to differentiate without compositional analyses. Of the 38 vessels and 16 vessel bodies that formed refits, 33 (22 vessels and 11 bodies) suggest in situ breakage and 17 (11 vessels and 6 bodies) illustrate a wide distribution throughout levels and quadrants in the deposit area, probably created through scattering.

Vessels and bodies that were broken in situ show varying degrees of burning. Vessel #6 was complete when deposited, but was excavated in seven fragments (Fig. 7A). The burn patterning along its exterior suggests that it was deposited whole, exposed to a single source of heat while still complete, and subsequently broken. Vessels and bodies that are more fragmented, however, suggest a different treatment and process of assembly. The four sherds that comprise Vessel #16 (Fig. 7B), for example (38.5 per cent complete), show continuous burn patterning along all shared margins of sherds with direct refits. This pattern is also noted in certain refit body fragments (Figs. 7C & 7D). The evidence of burning noted on the more fragmentary vessels indicates that burning was either part of the pre-depositional treatment or the observed burn patterns were artifacts of earlier use-lives. In the case of the latter, these fragmentary vessels would correspond to the ritual use of broken objects that, rather than being discarded, were set aside for future ritual work. When broken in situ, these potentially re-used vessel fragments were placed and stacked in the deposit without added burning, contrasting the treatment of complete vessels.

Figure 7. Selected vessel fragments mentioned in the text: (A) vessel #6; (B) vessel #16; (C) body #21; (D) body #23; (E) vessel #13; (F) vessel #1; (G) body #31; (H) graffiti sherd with head. All shown with 2 cm scales. (Photographs: David Del Cid, 2019.)

A total of 17 vessels were broken and then scattered throughout the deposit area. The associated sherds of Vessel #13 (Fig. 7E), an example of a complete vessel, were recovered in multiple, non-joining quadrants within 0.30 m of one another. These sherds were direct refits that presented different levels of heat exposure along their shared margins. As indicated by the distribution and burning on the associated sherds, this complete vessel was broken as a pre-depositional treatment where its broken fragments were added at different times to different places and exposed to varying levels of heat likely after deposition. Heat exposure observed on other refit vessels scattered throughout the deposit varied considerably. Notably, 29 of the 30 fragments comprising Vessel #1 show no signs of heat exposure despite their inclusion in contexts where burn patterning was noted on other vessel fragments. All 14 fragments of Body #31 demonstrate some degree of heat exposure; however, these patterns are shared across their exterior, but certain sherds exhibit distinct burn patterns on their interiors. These examples indicate a similar pre-depositional treatment. Prior to being scattered, placed, stacked and, in some cases, burned, these complete and highly fragmented vessels were broken into smaller fragments and added at different points in the process of assembly as well as in different locations.

Two sherds from the deposit were also incised with graffiti. One rim fragment presents a cross-hatching pattern, whereas another example, a body fragment, includes a human head (Fig. 7H). As they did not match other sherds within the recovered materials, either as direct or indirect refits, both sherds were identified as orphan sherds. One additional patterned modification was noted on Body #21, discussed earlier, where certain refit sherds present patterned peck marks across the exterior (Fig. 7C).

Also recovered within the deposit were 10 ceramic figurine fragments. These recovered fragments were all distinct: refits between them were not possible. However, certain figurines were deliberately broken; meanwhile, others may have a thematic relationship with the structure. Three figurine fragments depict human heads, two of which show that their noses or mouths were deliberately broken (Figs. 8A–C). As the cessation of breath, as opposed to the absence of a heartbeat, marked the end of life, these two figurines appear to have been sacrificed. A broad-brimmed hat worn by one of these sacrificed figurines appears to be similar to those worn by women vendors depicted in the Classic period Calakmul murals (Fig. 8A; Carrasco Vargas et al. Reference Carrasco Vargas, Vázquez López and Martin2009). This figure possibly represents a woman with a similar occupation. Another head fragment wears a headdress that appears to be a reptile with one eye open and one eye closed (Fig. 8C), suggesting a liminal placement, perhaps between night and day or death and life (Finamore & Houston Reference Finamore and Houston2010, 252). Another figurine fragment depicts a slightly different reptile (Fig. 8D): specifically, it is portrayed open-mouthed with its tongue exposed. The larger figurine fragments depict sections of human bodies. A particularly complete example depicts a seated woman with one breast exposed and a child holding on to her side (Fig. 8E). The other notable fragment depicts the lower, front half of a human body with a missing element positioned between its legs (Fig. 8F). This broken element is curious, given the context, perhaps alluding to birth with something or someone, now missing, emerging from between the individual's legs. This fragment is also the only figurine to be extensively burned.

Figure 8. Figurine fragments mentioned in the text: (A, B, C) representations of human heads; (D) depicts a reptile; (E) shows a woman and child; (F) appears to be the lower half of a human with evidence of burning. All scales 2 cm. (Photographs: David Del Cid, 2019.)

Human remains

The skeletal remains of a juvenile human were located just north of the sweat bath's doorway, both within a basin formed by the sweat bath's sunken drain and surrounded by an ashy matrix (Figs. 6C & 6D). This individual was excavated during the 2012 field season where, due to time constraints, the individual was excavated vertically rather than horizontally from a trench profile (Wildt Reference Wildt2015). Original documentation of the juvenile remains suggests that the skull corresponded to a 12-year-old individual, while the postcranial remains were from a different individual of 1.5–2 years of age (Wildt Reference Wildt2015, 173). Several years later, a more thorough analysis of these remains was conducted, which focused on preservation and the burial context, as well as age-at-death, taphonomic alterations and trauma (Hannigan Reference Hannigan, Hurst and Beltrán2019).

The recovered skeletal elements are relatively complete and well preserved. The sample includes a number of small bones, such as phalanges and unfused sacral elements (Fig. 9). Despite the preservation of these small bones, there were many skeletal elements missing: the right humerus, radius and ulna, the left scapula, nine vertebrae, three ribs, three deciduous incisors and a number of hand and foot bones. The incomplete nature of the skeleton and its apparent disarticulation prevent a confident classification as a primary burial (Duday Reference Duday2009, 25). Neither do the well-preserved skeletal elements indicate a secondary burial context following Jones’ (Reference Jones2018, 220) definition: ‘the collection and redeposition … of skeletal elements in a location different from the original place of decomposition’. These discrepancies suggest that the juvenile interment may have been a primary burial that was altered through secondary treatments, defined by Moutafi and Voutsaki (Reference Moutafi and Voutsaki2016, 784) as ‘complete or partial disarticulation, selective or random bone removal and/or retention, limited or extensive relocation inside or outside the grave’. It is possible that some of the missing elements are the result of an incomplete recovery at the end of the 2012 excavation. It is just as possible that the missing juvenile elements were removed from the primary burial in antiquity, following decomposition. Such behaviour has precedents in Maya mortuary practices. Bone removal from primary interments is documented in several cases (e.g. Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Chase1994; Novotny Reference Novotny2017; Scherer Reference Scherer2015, 99), although this practice is rarely noted in offertory contexts (cf. Ambrosino Reference Ambrosino and Christie2003; Domenici Reference Domenici and Wrobel2014; Tiesler Reference Tiesler, Tiesler and Cucina2007).

Figure 9. Juvenile skeleton. Vertebrae are organized into groups of cervical/thoracic/lumbar but are not necessarily in the correct order; phalanges/carpals/tarsals are arranged at the base of the image; unsided and unidentified fragments/elements are located in groups left of the juvenile. (Photograph: David Del Cid., 2019)

The initial age-at-death estimations suggested that two separate individuals were represented in the juvenile remains (Wildt Reference Wildt2015). The age-at-death analysis for the older juvenile was conducted using tooth eruption, whereas the age range for the younger juvenile was constructed using the ossification rate of vertebrae (Wildt Reference Wildt2015, 173). In our reevaluation, an age-at-death estimation was constructed based on an analysis of ossification rates of various skeletal elements following criteria established by Scheuer and Black (Reference Scheuer and Black2000) and Schaefer and colleagues (Reference Schaefer, Black and Scheuer2009). Both a closed metopic suture and the lack of an anterior bar on the ventro-lateral aspect of the articular pillar of the first cervical vertebra indicate that the age-at-death of the individual was 2–4 years. This age-at-death estimate is also consistent for the entire skeleton including dentition, indicating that one, rather than two individuals are represented.

The inclusion of this juvenile individual within a problematical deposit appears to be uncommon. Similar deposits, defined as either a termination or problematical deposit, rarely include juvenile human individuals (cf. Iglesias Ponce de León Reference Iglesias Ponce de León1988; Wrobel et al. Reference Wrobel, Shelton, Morton, Lynch and Andres2013). Instead, the remains of human individuals of this age are more commonly included in deposits that are interpreted as sacrificial offerings (e.g. Kieffer Reference Kieffer2015; Massey & Steele Reference Massey and Steele1997; Scherer Reference Scherer, Garrison and Houston2018; Tiesler et al. Reference Tiesler, Cucina and Romano Pacheco2002; Reference Tiesler, Chinchilla Mazariegos, Chi, Chay, Gómez, Arroyo and Méndez Salinas2012) or related to acts of ancestor veneration (e.g. Carroll Reference Carroll2015; Hotaling et al. Reference Hotaling, Saturno, Beltrán and Suzuki2017; Źrałka et al. Reference Źrałka, Koszkul, Hermes, Velásquez, Matute and Pilarski2017). However, observations pertaining to perimortem trauma noted during our analysis prevent the interpretation of sacrifice for this individual.

Cut marks or other perimortem trauma were not indicated on the individual's remains. While evidence of burning was present on one half of a vertebral neural arch, it was absent from all other studied remains. Because evidence of perimortem trauma is widely used to determine if juvenile remains were sacrificial offerings, the dearth of osteological evidence, in this case, presents a challenge. Burning as a method of juvenile sacrifice is commonly documented among the Classic Maya, where evidence of burning is pervasive and clearly exhibited on the skeletal remains (e.g. Chinchilla Mazariegos et al. Reference Chinchilla Mazariegos, Tiesler, Gómez and Price2015; Scherer Reference Scherer, Garrison and Houston2018). However, not all methods of perimortem trauma leave clear evidence. Different methods of heart extraction, as Tiesler and Cucina (Reference Tiesler and Cucina2006, 59) illustrate, do not present evidence of perimortem trauma. Children sacrificed as an offering to water/earth/fertility deities, according to Domenici (Reference Domenici and Wrobel2014, 57), were killed by drowning or throat slitting, actions that often do not leave discernable marks. The absence of perimortem trauma exhibited on the juvenile's remains, therefore, does not dismiss the possibility that this individual was included in this deposit as an offering.

Faunal assemblage

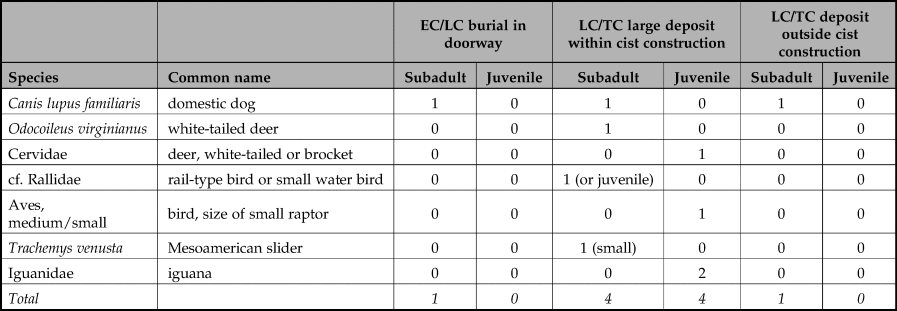

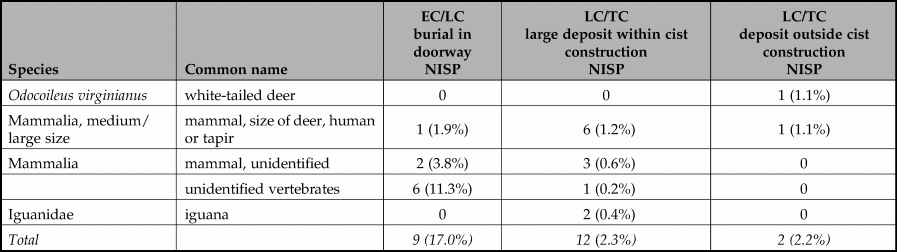

Specimen counts for animals are reported as number of individual specimens (NISP) and minimum number of individuals (MNI). NISP was calculated conservatively, in that fragmented single elements from the same context were counted as one specimen, rather than individual fragments (for example, four pieces of a dog humerus were counted as one humerus, unless other characteristics such as size or side could clearly lead to the identification of two dog humeri). Thus, while NISP overestimates the number of individual animals in the deposit, it provides a close approximation of the number of individual bone elements recovered. In the cases of armadillo scutes and turtle shells, the number of scutes and carapace fragments are reported, along with a conservative estimate of the number of entire armadillo or turtle shells. MNI was quantified by estimating the minimum number of individual animals based on characteristics such as repeating elements of the same side, animal ages and chronological periods. MNI thus provides a better estimation of the true number of animals. In addition to species identifications and element counts, other characteristics were noted, including animal bone fusion and age, evidence of natural modifications such as root etching and rodent gnawing and evidence of burning, cut marks and other anthropogenic modifications.

Supplementary Table 2 shows the overall results of the fauna analysis, organized by construction phase and time period. The fauna are divided among four categories: the Early/Late Classic period fill from within the sweat bath chamber; the Early/Late Classic period burial located in the doorway that was partially removed; the Late/Terminal Classic period problematical deposit in front of Los Sapos; and the Late/Terminal Classic period remains from deposits found on the west façade and further east along the north facade. Significantly, 79.4 per cent of all faunal remains were recovered from the problematical deposit. The remainder of this section will focus on this context.

The majority of identified animal bones were iguanas (Iguanidae, 23.4 per cent overall). Cane toads (Rhinella marina) and unidentified toads or frogs (Anura) were the second most common animals by NISP (17.1 per cent), although deer bones, particularly those of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), were also common (11.6 per cent). Unidentified mammal long bone shaft fragments may have belonged to humans, deer, dogs, or any of the other medium-to-large mammals. Birds made up almost 20 per cent of the material, and those identified were mainly turkeys (Meleagris sp., 3.5 per cent) and water birds (2.4 per cent). Attempts were made to identify the iguanas, anurans, turkeys and fragmentary bird bones down to exact species, but without a direct comparative collection on hand this would be impossible in most cases. Based on the teeth shape of the iguanas, it would appear at least one is a green iguana (Iguana iguana). Future analyses of the material, preferably with comparative physical specimens of the different reptile, amphibian, and bird specimens, would allow for more precise identifications of individual taxa.

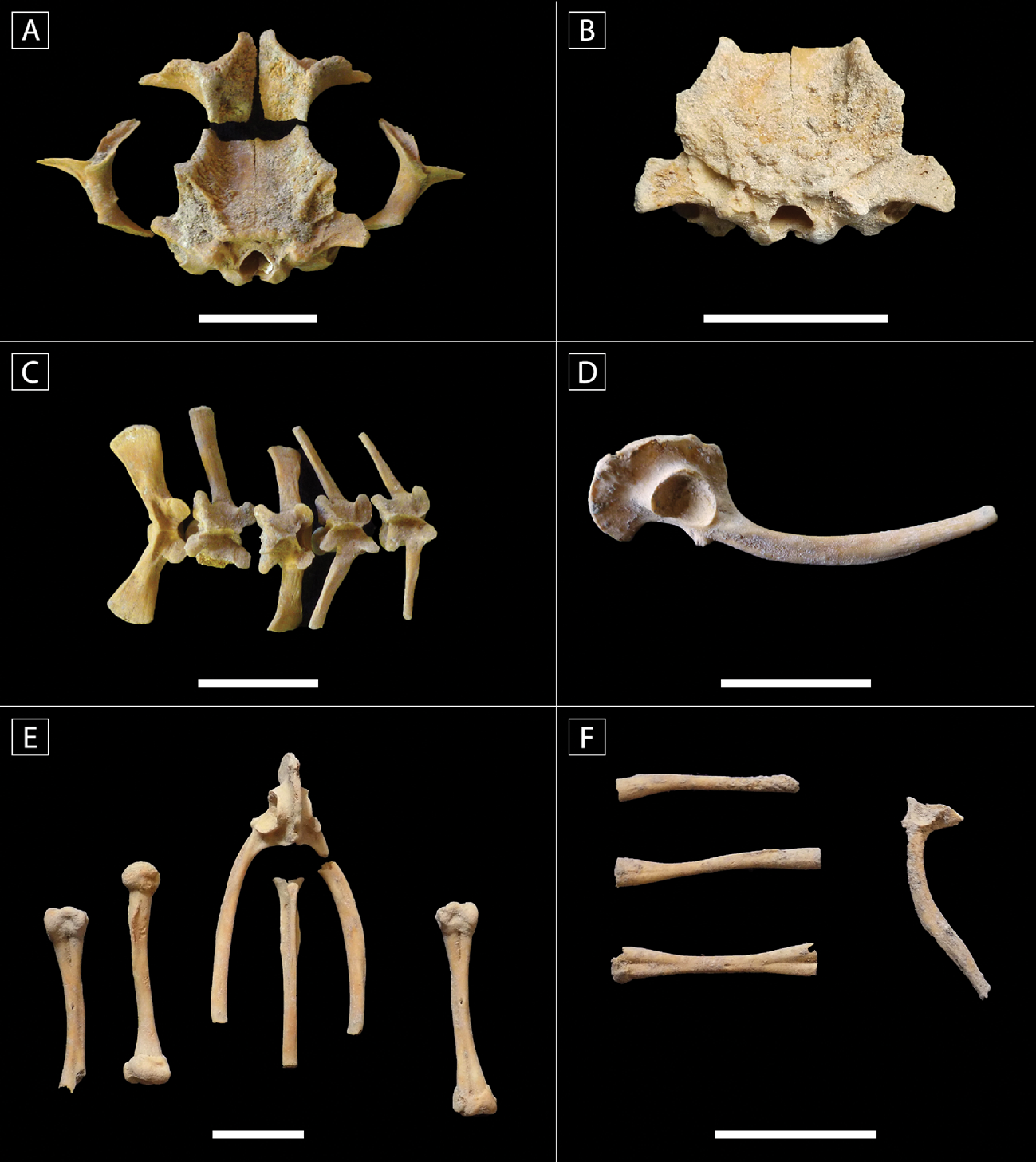

The analysis of the minimum number of individuals reveals a more accurate assessment of the number of animals (Supplementary Table 2). At least 30 individuals were recovered, 26 of which were vertebrates, along with four shells. The shells were found clustered together, and include two freshwater species (an apple snail and a freshwater mussel), and two marine gastropods (an olive shell and small conch); all except the mussel were intentionally modified with cut marks or drilled holes. Most vertebrate taxa were represented by one individual each, although in some cases there were multiple individuals of the same taxon, which may have been intentionally placed. For example, there were two partial gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) crania (Fig. 10), although no other gray fox skeletal elements were recovered, suggesting that the crania were placed alone in the deposit. Scattered throughout were three adult white-tailed deer skeletons, along with a fourth juvenile deer that may have been the same species, but due to its young age (all elements were unfused), it was impossible to discern whether it was a juvenile white-tailed deer or a brocket deer (Mazama sp.). At least three water birds that resembled rails (cf. Rallidae) were also recovered, and appear to be older juvenile or subadult individuals based on their lack of fully developed leg bones.

Figure 10. Two partial parietal/frontal bones from a gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) cranium. Scale 2 cm.

There were also four iguanas, including two large and two small individuals, based on their size and repeating same-sided elements (Fig. 11). The iguanas appear to have been deposited originally as complete skeletons, since many cranial and postcranial elements from the four individuals were recovered; likely the missing fragments remained in the parts of the deposit that were not excavated, or deteriorated post-deposition. Finally, two large adult cane toads and at least one (although possibly two based on differences in size) small unidentified frogs or toads were also found (Fig. 12). It is unlikely that the iguanas and toads were chance intrusions in the deposit, in part because the deposit was sealed, because these animals cannot burrow several metres into soil, because there was a lack of the more common intrusive animals usually found in Maya deposits (i.e. rodents) and because, as will be mentioned, some of the iguana bones were burned.

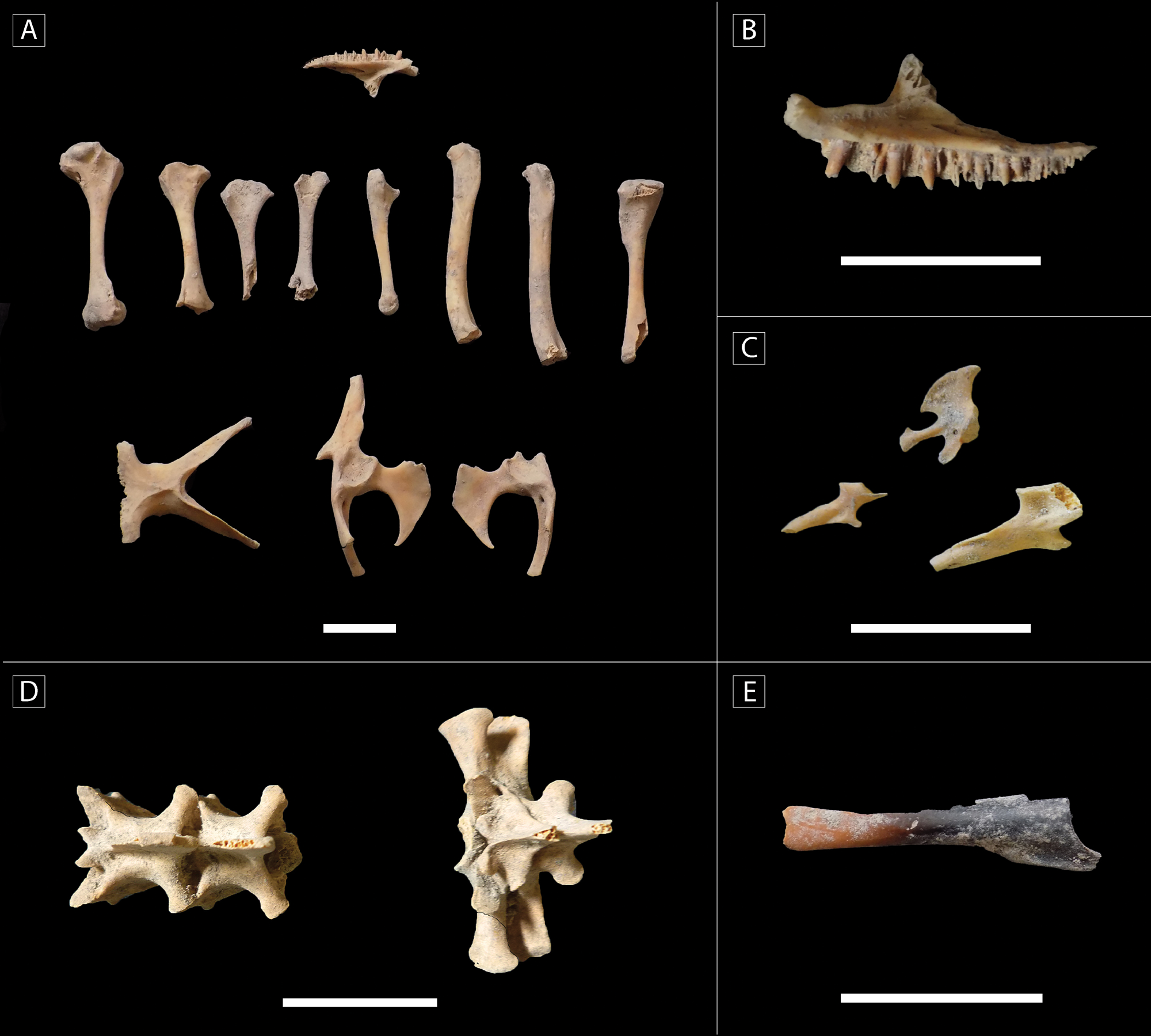

Figure 11. Some of the skeletal elements belonging to the four iguanas (Iguanidae): (A) mixed skeletal elements (humeri, femurs, tibia, ulna, maxilla, sternum, and pelvis); (B) maxilla, close-up; (C) unfused pelvic bones belonging to juvenile iguanas; (D) large thoracic and lumbar vertebrae of an older individual (note these two sets of vertebrae are fused); (E) a burned ulna. All scales 2 cm.

Figure 12. The assortment of toad bones placed in the offering: (A) cranium of one of the large cane toads (Rhinella marina); (B) partial cranium of the second large cane toad in the offering; (C) vertebrae of large cane toads (mixed, from both toads); (D) innominate (pelvis) of one large toad; (E) assorted elements from a large cane toad (tibiotarsi, humerus, pelvis, urostyle); (F) assorted elements from a small toad or frog (humeri, tibiotarsus, pelvis innominate). All scales 2 cm.

As Table 2 shows, many animals added to the deposit were juveniles or subadults. As was mentioned, the partial skeleton of a very young deer was included. The unfused radius of a dog was also recovered, indicating it was less than a year old. Concerning the possible rail birds, two tibiotarsi and two tarsometatarsi had unformed/fused ends, suggesting these belonged to a juvenile bird (Fig. 13). In the case of the iguanas, there were at least two larger and two smaller, and therefore younger, individuals.

Figure 13. Examples of juvenile animals in the deposit: (A) leg elements of a young stilt-legged bird (femur, tibiotarsi, tarsometatarsus; note proximal ends of bones are not yet fully developed); (B) unfused pelvic bone of a very young deer; (C) unfused humerus missing proximal head of a subadult deer, an older individual than B. All scales 2 cm.

Table 2. Subadult and juvenile individuals recovered from different contexts, according to MNI estimates. Subadults are near-adult size with unfused or fusing appendages. Juveniles have unfused appendages and are considerably smaller than adult size. No young animals were recovered from the EC/LC construction fill context.

For the most part, evidence for burning was limited (Table 3). Only 2.3 per cent of specimens in the deposit were burned. Burning does not appear to be concentrated in a particular area. Interestingly, two of the iguana bones were burned black, including a partial ulna and the spinous process and arch of a broken vertebra (found near but not adjacent to each other). This indicates that, although the entire termination deposit consisted of an ashy matrix, most of the bones were not exposed to flame. Except for the clearly burnt bones, most do not exhibit the signature browning inherent in bones placed near a heat source. It is likely the iguanas were deposited as articulated skeletons and not defleshed, since cranial and postcranial elements are represented, and vertebrae tend to be found concentrated in certain lots. The burnt elements appear to be the result of exposure to a short-lived flame.

Table 3. Evidence of burning within the assemblages. Percentages based on number of individual specimens within the context area, including unidentified vertebrates but excluding terrestrial snails. No evidence of burning was recovered from the EC/LC construction fill context.

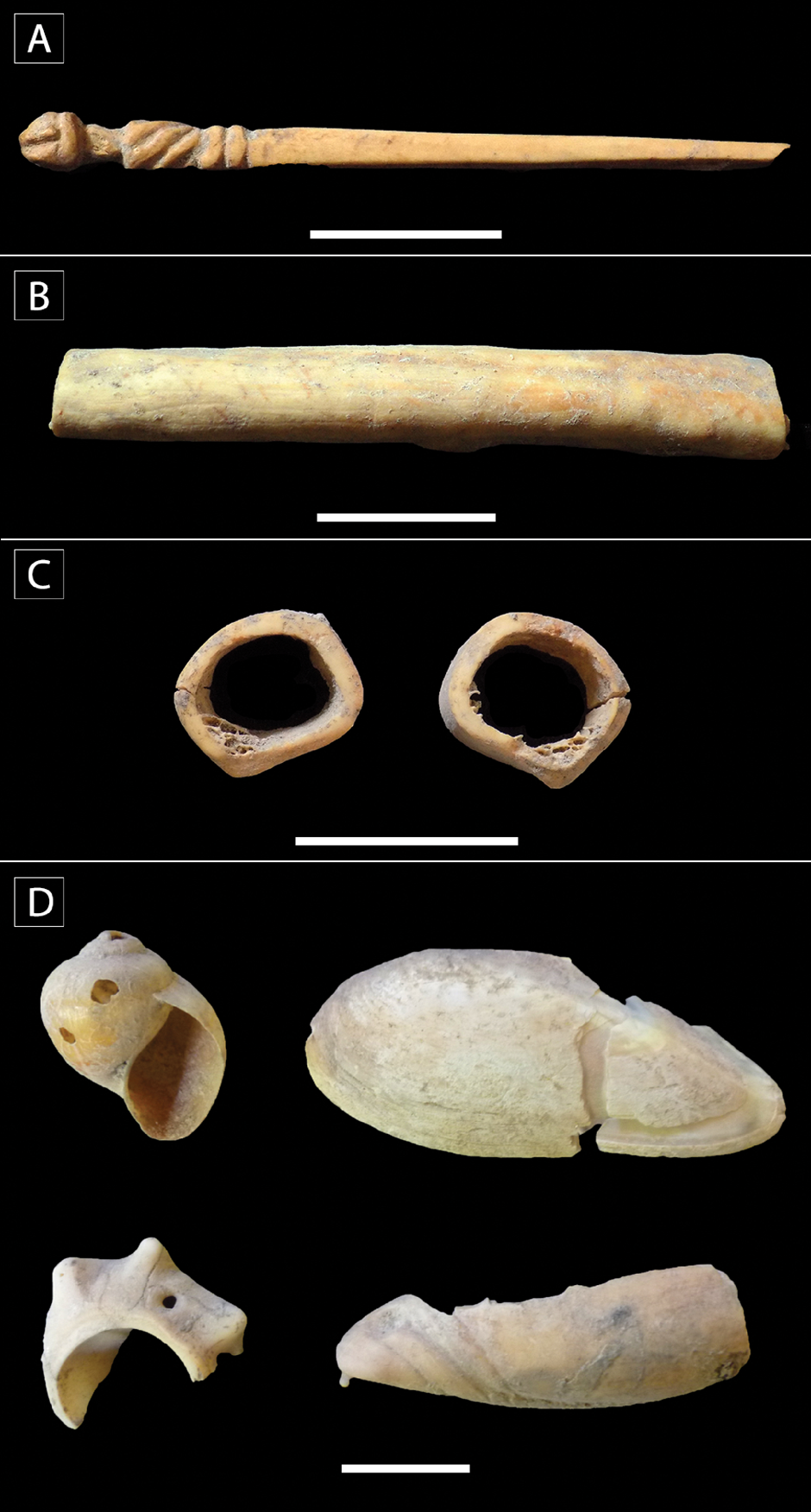

There is slightly more evidence of cutting, incising and polishing of bones, as well as most of the shells (5 per cent of specimens) (Fig. 14). These artifacts appear to have been crafted for ornamentation, hinting at their life before final interment with the deposit. Three of the dog bones were cut, two in the form of bone tubes. At least five mammal bone pins were recovered, two of which appeared to be either a broken fragment or an awl in the process of production, possibly formed from a deer antler. Three large bone rings carved into possible beads were recovered as well, at least one carved from what appears to be the humerus of a white-tailed deer. Only three bones were found with potential butchery-style cut and scrape marks, although since these were fragments, we cannot rule out that these, too, may have been the results of crafting activities.

Figure 14. Examples of bone artifacts found in the deposit: (A) a finely crafted pin; (B) one of the bone tubes found in the deposit, this example having been carved across the exterior surface and not possible to identify to species; (C) two ‘rings’, probably cut from the same bone; (D) the four shells found together in the deposit: an apple snail (Pomacea flagellata), a freshwater mussel (Unionidae), a fighting conch (Strombus pugilis) and an olive shell (Olividae). All scales 2 cm.

Evaluating relational ontologies at Los Sapos

Originally classified as a problematical deposit, comprehensive analysis of the items included in the Los Sapos offering presents an opportunity to evaluate the means to which materials mediated a ritual discourse. This offering reflects a series of actions that aimed at converting offerings into essence in the hopes of generating real change in the present. In some cases, burning was the means of conversion. Certain items were carefully placed into the deposit as whole objects as the fire within the vacated cist tomb was blazing, whereas others were added as the fire began to cool and burn unevenly. The latter appears to be the case with the juvenile human individual as well as certain fauna and ceramic vessels, each reflecting different levels of heat exposure. Incomplete materials showing evidence of extensive use-lives, such as ceramic materials and worked bone, particularly the broken pins, were also included in the offering. Only select items within this ritually repurposed refuse were acted upon. While some were burned, most were broken or smashed and then scattered or intentionally stacked within the offering. Although certain contents were intentionally placed, we did not identify a pattern in the assembly that indicates either the position of or the spatial relationships between placed items were significant. That said, there do appear to be thematic relationships among the offered items.

The artifacts included in the deposit reflect a certain logic in that they appear to have been chosen at least in part because they had a direct association with the structure's identity. This is perhaps most evident in the juvenile human remains, the juvenile deer and bird bones and the figurine of an aged mother, all of which relate to notions of birth and parturition. These related offerings can be attributed to the sweat bath's function as a place of birth and purification, but also the primordial place and generative role attributed to the goddess ‘ix.tzutz.sak’. There is also a clear bias towards aquatic animals. The four clustered shells, rail birds, iguanas, and cane toads recall the watery iconography that surround representations of this deity and the characterization of Matwil, the primordial place she is said to embody at Palenque. It cannot be determined for certain, but it appears that the number of shells, toads and iguanas was significant, and may have been four (in the case of the toads, it was difficult to discern whether there were three or four). Iguanas were known to be consumed during feasts, such as described by Landa in the Yucatan Postclassic Muan festival (Tozzer Reference Tozzer1941, 164); a mix of multiple iguanas and toads, however, seems to be unique to this deposit, especially given that they were also represented as figurine fragments. It would appear that they were intended to mimic the structure's external iconography; however, based on the ceramic materials from fill surrounding the structure, the façades were probably hidden from view at the time of re-entry. The individuals who made the offering were not those that used the sweat bath, since Los Sapos had been entombed for approximately 200–300 years by the time the final offering was put in place. Therefore, the inclusion of thematically related materials suggests that this figure's identity may have been preserved in part of a social memory. Indeed, personified sweat baths are found throughout Mesoamerican history, many of which continue to hold important roles as social actors within contemporary Maya communities. For most of Mesoamerican history, indigenous perspectives of the personified sweat bath have had much in common. In order to secure the conditions for human life, the twin heroes killed the ferocious and cruel grandmother goddess after which she became the sweat bath. These structures are mother and grandmother figures who may offer help or elect to destroy or consume a living population.

The connections between modern or historic conceptions of sweat baths and those of the Classic period are admittedly tenuous, although they are not entirely absent. For example, old goddesses are represented as midwives aiding in scenes of supernatural birth (Taube Reference Taube, Kerr and Kerr1994). What remains unclear, however, is if these old goddesses were understood as the mythological figures who, as a result of being defeated, became the sweat bath. The limited iconographic sample from Classic period Maya sweat baths instead show that the reptilian goddess ‘ix.tzutz.sak’ embodied these structures; this relationship perhaps also indicated an antiquity to the process of her becoming the sweat bath, one that was anchored in social memory and perhaps recounted as myth. The individual recovered within the doorway of Los Sapos may support this interpretation. Burning was observed on these human remains, but their fragmentary nature prevents a conclusive identification of the individual's sex, and also yields a wide age range of 12+ years (Hannigan Reference Hannigan, Hurst and Beltrán2019). Perhaps alluding to her defeat, ‘ix.tzutz.sak’ is also depicted in a manner similar to defeated captives. As illustrated in the Yaxha examples discussed earlier, rulers perform period renewal rituals—actions tied to those of the hero twins that secured the conditions for human life—while standing on top of her head or within her mouth. Similar performed interactions are suggested by the Los Sapos architecture; one ascended the body of ‘ix.tuztz.sak’ in order to stand on top of her head or within her mouth. Although these connections remain loosely tied to later accounts of Mesoamerican mythology, our evidence indicates that long after Los Sapos had been entombed, the Xultun population re-entered the cist tomb, removed most of an individual's burned remains and negotiated with the embodied entity. Their actions and offering suggest that, although buried, this personified sweat bath continued to have an active role in Xultun society well into the Terminal Classic period.

Xultun's permanent abandonment followed shortly after the deposit's assembly. Depopulation of the site had begun around c. ad 650–780, but the site's reservoirs, the primary sources of water, continued to be maintained until about cal. ad 980–1080, suggesting continued occupation. This gradual process of what is popularly referred to as the Maya ‘collapse’ can be seen across the Petén. As sites throughout this region were no longer engaging in monumental projects, Xultun inhabitants were still attempting to hold on to their Classic period reality. Not only did they commission and erect a new monumental stela, the last known in the Petén region; they also made this elaborate offering. By burning, breaking, suffocating and otherwise sacrificing the deposit's contents, they fed the supernatural being embodied in Los Sapos a considerable sum of vital life force or k'uh. The inclusion of a juvenile human alongside other references to birth are particularly significant, as they reflect traits held in common among the goddesses embodied in Mesoamerican sweat baths. The identity and agency of the reptilian deity ‘ix.tzutz.sak’ was perhaps similarly understood. As the analogous examples suggest, this pernicious persona is ‘consonant with the notion of the earth as a voracious mother who yields her fruits reluctantly and ultimately consumes her children’ (Chinchilla Mazariegos Reference Chinchilla Mazariegos2017, 128). Given this identity and her perceived agency, an offering on this scale was most certainly an attempt at negotiation. Not yet ready to be the consumed children, Xultun inhabitants sought to pacify this being by offering her an exchange or offered substitution, akin to k'ex offerings discussed by Taube (Reference Taube, Kerr and Kerr1994). The conditions leading to this offering may have been understood as the supernatural entity attempting to expel them from the landscape possibly considered under her control. Rather than being a casual or convenient collection of both ritual and refuse items, the contents of the Los Sapos offering may, therefore, be an act of resilience, a strategy employed by a population seeking to maintain its hold on life at Xultun.

Conclusions

Although it is frequently difficult to determine the motive and history behind the placement of a ritual deposit in Maya archaeology, the circumstances of the Los Sapos sweat bath, with its unusually well preserved outer façade and intact offering within, allow a rare opportunity to assess such a practice. Careful excavation and stratigraphic dating retrace the history of the deposit, revealing that the final large offering took place centuries after the sweat bath had been ceremonially buried. The offering's content, including a human child, juvenile and aquatic animal remains and birth and parturition symbolism exhibited on the figurines, demonstrate associations with the sweat bath's later iconic role during the Postclassic and post-Contact periods as a place where women give birth. The cane toads and iguanas in the offering are a direct reference to the painted and sculpted stucco façades, indicating that those who made the deposit were familiar with what had been on the outside surface, even if they could no longer clearly see it during the Terminal Classic period. The Early Classic depiction of a crouching figure with limbs composed of iguana–toad conflations, perhaps the goddess ‘ix.tzutz.sak’, enveloped the structure, and may have been understood as both an embodied entity and the intended recipient of the final offering. Had the Los Sapos structure lacked its external façade, our ability to interpret the offering's contents would have been limited. Furthermore, if the contents of the offering had not been dated in association with the surrounding matrix, we may have misidentified this offering as a problematical or termination deposit made when the building was buried, rather than centuries later.

The similarities and differences among problematical deposits, we argue, suggest a common logic to ritual work among the Classic Maya. Although we cannot read the entire transcript of this discourse, it does not eliminate the reality that other layers of meaning (such as the significance of colour or texture, the representative nature of the items, be it social or geographic) were understood by those present during assembly. The distinctions we draw between the prescribed and specific—repurposed refuse in comparison to materials thematically related to place—do not aim to elevate one class of material above the other, but rather to evaluate how particular negotiations may be understood within the material assemblages that have, for the most part, been broadly classified. Because the function of the sweat bath Los Sapos is understood and its personified identity visually represented on its surfaces, we are able to illustrate the presence of an ontological relationship and question how this deposit reflects a material discourse between human and non-human populations. While it is not always possible to reconstruct such connections, our data suggest that the selection, treatment and assembly of problematical deposits were particular to circumstance and tailored to place.

Acknowledgements

This paper has profited immensely from discussions with many people over the years: Sarah Newman, David Carballo, Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos, Alexandre Tokovinine, Julia Guernsey, Stephen Houston, David Stuart, Karl Taube, Bill Saturno, Franco Rossi, Elisa Mencos, David Del Cid, Edwin Román Ramírez, Jenny Wildt, Martin Rangle, Jane Rehl, Laura Health-Stout, Catherine Scott, Maria Codlin, Kathleen Forste. We would like to acknowledge the members of the Dolores, El Cruce, Santa Elena, Uaxactun, and other communities who shared their expertise and contributed to the recovery of this deposit. Finally, the paper has also profited from funding by Holden Williams, the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, National Geographic Society Expeditions Council Grant (#EC0655-13), a David Scott Palmer award from Boston University's Center for Latin American Studies, and Boston University's Archaeology Program.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Tables 1 & 2 may be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774320000281