Animals—particularly livestock—form key yet still significantly undertheorized components of early state political economies. Across the long history of thinking about the origins of the state and the workings of state finance in preindustrial contexts, scholars have highlighted the formative roles played by technologies like crop cultivation, storage, irrigation networks and recording systems (D'Altroy & Earle Reference D'Altroy and Earle1985; Hirth Reference Hirth2020; Wittfogel Reference Wittfogel1957; Wright & Johnson Reference Wright and Johnson1975). And while many have articulated the important roles of livestock and pastoralism in early states (e.g. deFrance Reference deFrance2009; Zeder Reference Zeder, Rothman and Stein1994), these approaches have tended to view animals as interchangeable with other agricultural products. That is, animals are depicted simply as a source of calories, protein, or fibre. While important, the relegation of the value of livestock to the realm of subsistence has tended to flatten the particular qualities of livestock—including their mobility, their nature as animate beings, and their relationships of interdependency with human caretakers—which frequently made them subject to intense political attention. In this article, we argue that livestock represented a special category of wealth in early states that merits further analysis. Examining the politics and economics of the early state through the lens of the animal not only restores an important element to our analyses of state societies, but also allows us to trace vital connections across multiple dimensions of state power and its limits. We demonstrate this approach in two case studies: the Inca in the central Andes and Ur III in southern Mesopotamia.

Political economy, livestock and approaches to the early state

In placing animals centre-stage in the analysis of early states, we follow the lead of other ‘social zooarchaeologists’—as well as the wider ‘animal turn’ across the humanities (Boyd Reference Boyd2017)—who have begun to examine the place of animals within socio-political structures (Arbuckle & McCarty Reference Arbuckle, McCarty, McCarty and Arbuckle2014; deFrance Reference deFrance2009; Grossman & Paulette Reference Grossman and Paulette2020; Russell Reference Russell2011). While much previous work has focused primarily on the consumption of animals (particularly through the ever-popular lens of feasting), we argue that animals acted as a complex ‘glue’ that held together multiple domains of the body politic. As stores of value, objects of taxation and tribute, means of production, pack animals, and key military elements, domesticated livestock in particular were crucial to state finance and territorial integration. As animate beings that were owned and controlled, they supplied both walking metaphors of political subjectivity (Arbuckle & McCarty Reference Arbuckle, McCarty, McCarty and Arbuckle2014) and the media for sacrificial and divinatory spectacle (McAnany & Wells Reference McAnany, Wells, Wells and McAnany2008). At the same time, animals allowed some households and other social groups various levels of autonomy from the dominance of the early state (e.g. Salzman Reference Salzman2004; although see Honeychurch Reference Honeychurch2014). Documenting these dimensions, and the tensions between them, are vital components to an integrative approach to the political economies of early states.

With our examination of livestock in early states through the lens of ‘political economy’, we situate our intervention within a broad tradition of historical materialist analysis that foregrounds the relationships between state making and the realms of material production and reproduction (Earle Reference Earle2002; Smith Reference Smith2004). The term ‘political economy’ refers to the ways in which the production, distribution and consumption of human labour and its products determine pattern the access to and reproduction of power within a society (Roseberry Reference Roseberry1989, 44; Earle Reference Earle2002, 1). In line with this approach, we begin with the premise that, among other core functions, states are built around institutions concerned with the hegemonic appropriation, management and circulation of resources including land, water, human labour and livestock (D'Altroy & Earle Reference D'Altroy and Earle1985; Rosenswig & Cunningham Reference Rosenswig and Cunningham2017).

Yet the mobilization of multiple forms of wealth—including livestock—in projects of state finance also articulates with other sources of social power. Mann's (Reference Mann1986) analytical framework usefully distinguished ideological, economic, military and political sources of power. While we differ from Mann in giving greater primacy to the economic, his broadly integrative approach encourages us to consider the multiple sources of social power and to think creatively across divergent perspectives on the state. Building on this framework, we can systematically explore how livestock played key roles not only in expanding the economic sources of power of early states, but also facilitated the exercise of violence, the integration of new territorial forms, and projects of subject formation.

As scholars from Max Weber to Charles Tilly have argued, the exercise and control of violence forms a key basis for the reproduction of state power. The development of both military ‘war machines’ and ‘ritual economies’ predicated upon the violent destruction of humans and animals not only reproduced the military and ideological sources of power, but, in necessitating the mobilization of resources, had significant implications for strategies of institutional finance. As the case studies suggest below, finance in early states often focused on supplying animals—as sacrificial victims, means of transporting materiel, and, indeed, active participation in combat—for the purpose of state-sanctioned violence.

The state as the political ordering of territorialized space forms a related perspective that runs through much of the seminal literature on state formation, both ancient and modern (Anderson Reference Anderson1979; Smith Reference Smith2015). This approach foregrounds the state as a particular spatial scale, with fundamental implications for economic connectivity, military coercion and claims of political sovereignty. While not a necessary condition for large-scale projects of integration, animals, in their ability to transport humans, things and themselves across broad swaths of territory, were repeatedly mobilized for these ends across the history of preindustrial states, particularly when we look over the long term at the emergence of expansive imperial polities.

The state as project of subject formation has coalesced more recently as a focus for inquiry, with the varied projects of both homogenizing and differentiating subjects forming a vital basis for rule. Drawing particularly on the work of Gramsci and Foucault, scholars have sought to understand how the experiences of labour, techniques of government and state-produced media combine to shape both the making of individuals into subjects and the development of state-oriented subjectivities (Alonso Reference Alonso1994; Kosiba Reference Kosiba, Papadopoulos and Urton2012). Animals have often played key roles in these dynamics, both as objects of institutionalized labour processes and as the sources of powerful naturalizing metaphors.

Finally, we recognize that states were (and are) incomplete projects (Graeber Reference Graeber2004; Scott Reference Scott2009). Particularly in ancient states, the claims of kings, governors and other institutional actors should be read not as reflections of political reality but as part of ‘a cohering discourse of desire’ (Richardson Reference Richardson2012, 4). In seeking to understand what early states could and could not do (Covey Reference Covey and Shimada2015; Yoffee Reference Yoffee2005), it can be insightful to critically examine the effective limits of state control and influence. As we show, even in the highly centralized cases of Ur III and the Inca, important (and often animalized) informal and autonomous economies lay partly or fully beyond the reach of the state.

Case studies

The two case studies—the Ur III state (c. 2112–2004 bce) in southern Mesopotamia and the Inca state (ce 1400–1532) in the central Andes—serve to illuminate our arguments in two important respects.

First, both are particularly well documented in comparison with many other early states. Unusually detailed insights into the Ur III political economy are possible thanks to the approximately 100,000 published cuneiform tablets (Englund Reference Englund, Papadopoulos and Urton2012, 431; Sharlach Reference Sharlach2004, 1–3). Early colonial texts by Spanish and indigenous authors have also provided fundamental insights into the Inca political economy (D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy2015; Murra Reference Murra1975), albeit with significant biases towards a top-down and often idealized vision of the workings of state administration. These textual insights are increasingly complemented by archaeological research, particularly in the Inca case, where the past century of archaeological research on the Inca has been substantial (Alconini & Covey Reference Alconini and Covey2018), with empirical results including a growing number of published zooarchaeological assemblages. By contrast, there are few published zooarchaeological data for the Ur III period, exceptions being the small assemblages from Nippur (Boessneck & Kokabi Reference Boessneck, Kokabi and Zettler1993) and Uruk (Boessneck Reference Boessneck1993).

Second, with their histories of rapid political expansion, highly centralized economies and extensive bureaucratic record-keeping, the Ur III and Inca empires stand as useful ‘limit cases’. Given that the production, circulation and consumption of livestock appear to have played particularly key roles in these two particular political projects (in contrast with, for instance, the Mexica in late preconquest Mesoamerica), the case studies outline the outer bounds of the potential impacts of animals on early state projects.

There are also important differences that separate the two cases. The alluvial plains and waterways at the core of the Ur III polity contrast with the Inca montane heartland. The Inca Empire was also much larger than the Ur III territory (1.96 million versus 256,000 sq. km, following maps in D'Altroy (Reference D'Altroy2015) and Steinkeller (Reference Steinkeller, Bang, Bayly and Scheidel2020)). The suite of domesticated mammals forms a third contrast. In the Andes, there were two large animals (llamas and alpacas [the domesticated camelids]), in addition to dogs and guinea pigs; a more complex package defined third-millennium Mesopotamia, including sheep, goats, pig, cattle, donkeys, dogs and horses.

Animals in the Ur III Period

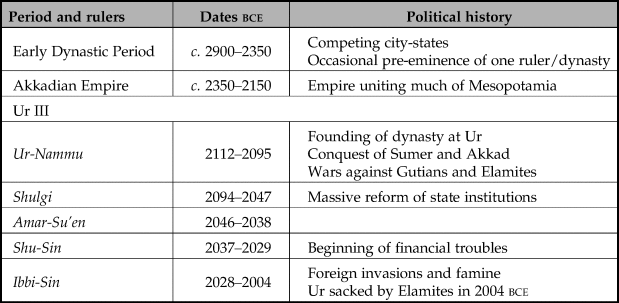

Ur III was the last major native Sumerian state in Mesopotamia. The dynasty began in 2112 bce, when Ur-Nammu, the governor of Ur, set out to conquer the other Sumerian cities (Table 1; Stępień Reference Stępień2009, 10–15). The exact nature of the Ur III state is much debated; here, we largely follow the interpretations of Steinkeller (Reference Steinkeller, Gibson and Biggs1987; Reference Steinkeller, Bang, Bayly and Scheidel2020), Stępień (Reference Stępień2009) and Sharlach (Reference Sharlach2004).

Table 1. Chronology of Mesopotamia during the third millennium bce.

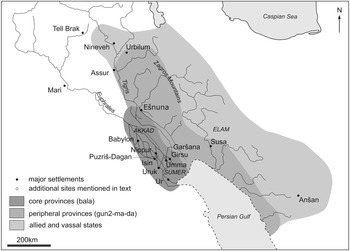

A pivotal moment for the Ur III state coincided with the 48-year reign of Ur-Nammu's son Shulgi, who introduced several major reforms. These reforms restructured Sumerian society into a streamlined imperial system. Some were ideological, including the formal deification of the king. Structural changes included the creation of a standing army and the standardization of bookkeeping, weights and measures and the calendar. The Ur III polity was also reorganized into three regions (Fig. 1), each with a unique relationship to state power and its fiscal regimes. The outer zone consisted of tribute-paying vassal states and allies. In the second zone, the peripheral provinces, the state settled soldiers, who paid taxes annually in animals to the state. Royal collection centres, especially Puzriš-Dagan, were set up to facilitate these transactions.

Figure 1. Map of the Ur III polity. (After Roaf Reference Roaf1990, 102.)

Within core provinces of Sumer and Akkad, the Ur III state placed a military commander (šagina), usually a non-local elite who reported to the crown via the sukkal-mah [state chancellor], in charge of royal estates. The crown also maintained royal ‘industrial’ complexes for the production of key commodities like woollen textiles. These royal domains existed in parallel to the traditional temple estates of each core province, which were placed under the administrative control of governors (ensi), usually a member of the local elite. Together, these institutional sectors existed side-by-side with more informal ones, including ‘private’ family-based production and exchange, mercantile activity and lending (Garfinkle Reference Garfinkle2004; Steinkeller Reference Steinkeller, Hudson and Van de Mieroop2002). Another potentially important economic sector was agricultural land collectively owned by kinship groups (Diakonoff Reference Diakonoff1974). To extract resources from the temple domains, the Ur III state instituted a taxation system (especially the bala) which required extensive mobilization of corvée labour from the free population (Klein Reference Klein and Sasson1995, 844–6; Steinkeller Reference Steinkeller, Gibson and Biggs1987, 16–17; Stępień Reference Stępień2009, 16–28).

Shulgi's three successors ruled the Ur III state for another 43 years (Stępień Reference Stępień2009, 28–50). Their reigns were characterized by increasing anxiety over foreign invaders, in particular the Amorites (Steinkeller Reference Steinkeller, Bang, Bayly and Scheidel2020, 67). The later years of Ibbi-Sin's reign saw famine and military disaster, with the defection of the governor of Isin and the Elamite sack of Ur in 2004 bce delivering the final blows to the Ur III state (Stępień Reference Stępień2009, 46–7).

Finance

Whether appropriated through taxation or raised directly within the royal domain, animals were a crucial means of finance. Here, we focus on the mobilization of domestic mammals—sheep, goats, cattle, and equids—although we recognize that fish (especially ‘carp’ suhurku6 or eštubku6) and fowl were also harvested, raised by specialists and collected by institutions in large numbers. Many temple administrations featured overseers of fowlers (ugula mušen-dù) and fishermen (ugula šu-ku6) (Borelli 2020). Regarding the mammalian livestock, the c. 12,000 texts from Puzriš-Dagan indicate that these species served multiple functions: the storage of value, provisioning for soldiers and other state dependents, sacrifices to gods (including the deified king) and gifts to elites (see e.g. Grossman & Paulette Reference Grossman and Paulette2020; Sallaberger Reference Sallaberger2004; Zeder Reference Zeder, Rothman and Stein1994, 180). In addition, caprines, cattle and equids were important means of production in both the core and the peripheral provinces: cattle and donkeys provided traction for cereal production, while sheep and goats produced fibre for textile production.

Animals functioned prominently in taxation, which took several forms in the Ur III state. The best-known of these is the bala (‘rotation’), obligatory payments in kind collected by the crown from the temple sectors of each of the two dozen core provinces (Sharlach Reference Sharlach2004). There is some debate about the flow of animals in the bala system (Adams Reference Adams2006; Englund Reference Englund, Papadopoulos and Urton2012, 457; Sharlach Reference Sharlach2004, 134–42; Steinkeller Reference Steinkeller, Gibson and Biggs1987, 24). Specifically, it is unclear whether the crown collected animals from the temple sector via the bala or merely distributed animals (especially cattle and sheep) back into temple domains. But in any event, animals took on a crucial role in mediating the relationships of indebtedness between ensi and king, province and empire via the bala system.

The crown extracted animal wealth in three ways. First, there were the masdaria obligations, paid by the ensi and other temple officials to the crown in livestock and silver (Sharlach Reference Sharlach2004, 162). Through this and other taxes, the crown collected large quantities of animal wealth. For example, the province of Lagash owed 10 per cent of sheep, goat and cattle offspring, as well as the same portion of the wool and dairy production each year (Englund Reference Englund, Papadopoulos and Urton2012, 457). Second, there was the gun2-ma-da [tax of the provinces], paid annually to the crown by soldiers settled in the peripheral provinces, drawing on the significant animal wealth of the piedmont and montane regions. Soldiers sent live animals—sheep, goats, cattle and sometimes gazelle or other wild animals—to Puzriš-Dagan (Adams Reference Adams2006; Michalowski Reference Michalowski1978; Sharlach Reference Sharlach2004, 162–3; Steinkeller Reference Steinkeller, Gibson and Biggs1987). Finally, raiding was a significant source of income and of animal wealth in particular (Garfinkle Reference Garfinkle, Neumann, Dittmann, Paulus, Neumann and Schuster-Brandis2014, 357).

While extracting animal wealth, the Ur III state also produced its own on its extensive royal domains. In addition to the royal domains operated by a šagina, in some case, the royal family directly controlled the temple economies of certain provinces, as appears to be the case at Ur and Uruk (Sharlach Reference Sharlach2004, 6). We know little about affairs of the royal domains, but the assumption is that they operated in the same way as the better-known institutional economies of the temples, where cattle, equids and especially caprines were amassed in large numbers. One text from Girsu (TUT 27:10’-r.8) indicates 74,533 sheep and goats in the temple's herds (Sallaberger Reference Sallaberger, Breniquet and Michel2014a, 106). The herd managed by the royal province of Ur is estimated to have included 320,000 sheep (Sallaberger Reference Sallaberger, Breniquet and Michel2014a, 106). Meat production, provisioning the armies and workers and the supplying of temples with sacrificial animals were major goals of institutional animal management (see Sallaberger Reference Sallaberger2004). Adams (Reference Adams2006, 144) speculates that the ‘centrifugal’ movement of animals from royal administrative centres to temples and provincial elite ‘may have been the real glue holding the empire together’. Secondary products also formed a vital aspect of institutional wealth accumulation. Cattle and, to a lesser extent, donkeys ploughed and prepared fields for cultivation (Borrelli Reference Borrelli2020, 46; Van Lerberghe Reference Van Lerberghe, Ismail, Sallaberger, Talon and Van Lerberghe1996, 114), facilitating the production of surplus grain, while sheep and goats produced wool/hair. Both of these commodities were essential for institutional finance, mobilized to supply dependent workers and consigned to merchants for exchange (Sallaberger Reference Sallaberger, Breniquet and Michel2014a, 97).

Political subjectivity

Within the imperial core, Sumerian society consisted of several status groups, each experiencing distinct political subjectivities mediated through labour appropriation (Englund Reference Englund, Papadopoulos and Urton2012; Steinkeller Reference Steinkeller, Garfinkle and Molina2013; Wright Reference Wright1998). Most Sumerians were erin2 [free citizens], a multi-class social category comprising smallholders, the ensi and everyone in between (Steinkeller Reference Steinkeller, Garfinkle and Molina2013). Adult male erin2 owed 15 days per month to the temple institutions, for which they were compensated in barley, wool, and other commodities and, for higher-ranker erin2, usufruct rights to plots of land (Englund Reference Englund, Papadopoulos and Urton2012; Wright Reference Wright1998, 64).

Below the erin2 were semi-free ‘menials’ (Steinkeller Reference Steinkeller, Garfinkle and Molina2013, 365) or ‘corporate slaves’ (Englund Reference Englund, Papadopoulos and Urton2012, 432) who belonged to institutions. They included UN-íl [male porters], guruš [male workers], and geme2 [female workers]. These individuals possessed few rights, but could not be bought and sold. Working full-time, they were provided with monthly rations of barley (30 l for women, 60 l for men) (Englund Reference Englund, Papadopoulos and Urton2012; Wright Reference Wright1998). Finally, though playing a minimal role in the institutional economies, sag (chattel slaves) were bought and sold with silver. They worked full time for similar minimum monthly rations of barley apportioned according to their gender (Wright Reference Wright1998).

Animals and their products played a significant role in the making of these subjectivities. First, the traction provided by cattle and donkeys acted as labour multipliers in surplus grain production, which was dispensed by institutions as rations to workers. Second, the increased scale of institutional livestock production relied on dependent and contracted pastoralist labour. Finally, wool production played a singularly important role in political subjectivity and (gendered) labour appropriation. Plucking, sorting, combing, dyeing, spinning and weaving all required massive labour investments (Breniquet Reference Breniquet, Breniquet and Michel2014; Firth & Nosch Reference Firth and Nosch2012, 72). For instance, 15,000 women worked in the institutional workshops of Lagash. Echoing textile labour practices in other time periods (from Inca workshops to the factories of the Industrial Revolution), the Ur III state followed long-standing Mesopotamian traditions in appropriating primarily female labour as textile production was scaled-up from the domestic to the institutional domain (McCorriston Reference McCorriston1997; Zagarell Reference Zagarell1986).

In addition to facilitating certain forms of labour and labour appropriation by institutions, we also suggest (pace Grossman & Paulette Reference Grossman and Paulette2020) that animals provided important metaphors of subjectivity in the Ur III state. Others have noted that Mesopotamian administrators treated humans and animals analogously (Algaze Reference Algaze2001; Tani Reference Tani2017). Bookkeepers punctiliously tracked the age, sex and health status in a schema that rendered both human labour and animal holdings as abstracted (and seemingly fungible) units of management. Additionally, royal texts mobilized pastoral imagery as a metaphor for political subjectivity, with the king referring to himself as a ‘shepherd of the people’ (e.g. Klein Reference Klein and Sasson1995, 848). This literary trope, taken up and expanded upon by later Mesopotamian dynasties, conveyed that the king protected his flock and provided it with abundance, while naturalizing kingly authority (Winter Reference Winter, Gibson and Biggs1987).

Violence

While animals were regularly sacrificed in large numbers as part of temple ritual activities, there is little evidence of the spectacles of mass animal slaughter seen in the Inca case. Nevertheless, animal imagery helped naturalize violence. As in other Mesopotamian dynasties, Ur III kingship was associated with lions, the archetypal enemy of livestock. Seals of Mesopotamian kings frequently depict the king wrestling lions and, by extension, protecting the herd. Yet, in a case of symbolic inversion, the king also was the lion. The paradox is clear in the praise poem ‘Shulgi, King of the Road’. Prior to claiming to be a shepherd of the people, Shulgi declares ‘I am a fierce-faced lion’ (Klein Reference Klein and Sasson1995, 848). The king as both shepherd and lion captures the contradictions at the heart of Mesopotamian statecraft, with its dual provision of security and violence.

The state also mobilized animals in military endeavours, especially donkeys or equid hybrids. Direct evidence for their use in the Ur III period is surprisingly limited. Nevertheless, the Standard of Ur, dating to the tweny-sixth century bce, suggests equids pulled four-wheeled battle carts (Ławecka Reference Ławecka2017) as well as transporting baggage and equipment. Tsouparopoulou and Recht (Reference Tsouparopoulou, Recht, Recht and Tsouparopoulou2021) also argue that dogs were used in warfare, with possible active roles in combat or scouting for the Ur III army.

Territorial integration

While much of the transportation in Sumer relied on waterways (Algaze Reference Algaze2001), animals played an important role in integrating territory under Ur III hegemony. First, equids facilitated overland trade, particularly with northern Mesopotamia and the Zagros. Indeed, donkeys figure prominently in texts and artwork in third-millennium northern Mesopotamian cities such Nagar (Tell Brak), Ebla and Mari (Sallaberger Reference Sallaberger, Butterlin, Margueron, Muller, Al-Maqdissi, Beyer and Cavigneaux2014b). Donkey-riding ‘mounted messengers’ (ragaba) were so common—and the flow of information that they enabled across the territory of the state so important—that their records comprise an entire genre of Ur III texts (e.g. D'Agostino & Pomponio Reference D'Agostino and Pomponio2002). Similar to Inca tambos, special rest houses (e2-kas4) were set up at regular intervals to provide food and rest for equids and their riders (Veldhuis Reference Veldhuis2001).

Second, through their periodic movement, animals served to connect productive pastoralist landscapes directly to the imperial core. This was perhaps most conspicuous in the collection of the gun2-ma-da, which created an annual stream of tens of thousands of animals flowing from the peripheral provinces to the royal collection centre at Puzriš-Dagan. In parallel with the mobilization and movement of soldiers across the empire, the state-driven flow of animals into the inner provinces would have made visible to all the hierarchical integration of Ur III territory.

Animals outside the state

The limited amount of zooarchaeological data makes our approach to animals outside the Ur III state indirect, since most texts document the administrative activities of the institutional economies. A few private (or semi-private) records exist (e.g. Nippur and Garšana), but exclusively from elite households; the Garšana texts, for example, document a royal family member's estate (Owen & Mayr Reference Owen and Mayr2007). These texts can hardly be taken as representative of everyday economics across the household and informal sectors, but they do offer some insights.

One striking contrast between the private household texts and those of institutions from Puzriš-Dagan, Umma, Girsu and Ur is the mention of pigs. The Garšana documents, for example, mention the construction of piggeries (é-šah) (Owen Reference Owen, Lion and Michel2006). This situation contrasts with extremely few references to pigs in the institutional corpus. Pigs were important features of the household and informal sectors of the Sumerian economy, perhaps even the dominant source of meat in some households. Indeed, among the published Ur III faunal assemblages, pigs are the most common taxon (45 per cent NISP) at Nippur (Boessneck & Kokabi Reference Boessneck, Kokabi and Zettler1993) and represent 32 per cent of the fauna from Uruk (Boessneck Reference Boessneck1993). The relative lack of textual attestations of pigs does not indicate that pork was unimportant in the Sumerian diet, but rather suggests that Ur III state institutions almost completely ignored this major feature of the agropastoral economy.

In addition to pigs, much sheep and goat herding must have taken place beyond the gaze of the state—or, indeed, in opposition to it or its goals. While the steppe-sown dichotomy has been critiqued (e.g. Arbuckle & Hammer Reference Arbuckle and Hammer2019; Makarewicz Reference Makarewicz2013), mobility afforded by caprine herding could have offered an escape route from the state (Salzman Reference Salzman1999, 38). On a more mundane level, the nature of institutional sheep and goat herding probably provided opportunities for graft. Ur III texts record contracts between herders and officials, deliveries of animals, biannual corralling of sheep for plucking and accounting of dead stock. They do not, however, document animal management itself, which took place beyond the direct gaze of the state (Adams Reference Adams2006). In fact, Adams (Reference Adams2006) argues that shepherds (sipa) in the Ur III texts often acted more as liaison between administrators and on-the-ground animal caretakers. Herders may have had a significant amount of liberty in deciding where and how sheep and goats were managed and the possibility for skimming may have been tempting—and perhaps even necessary given the high risks and low rewards faced by herders in Ur III contracts (Adams Reference Adams2006, 149). Tani (Reference Tani2017, 125–50) suspects skimming from institutional herds occurred frequently based on expected and reported birth rates and herd losses in ancient Mesopotamian texts.

Animals in the Inca Empire

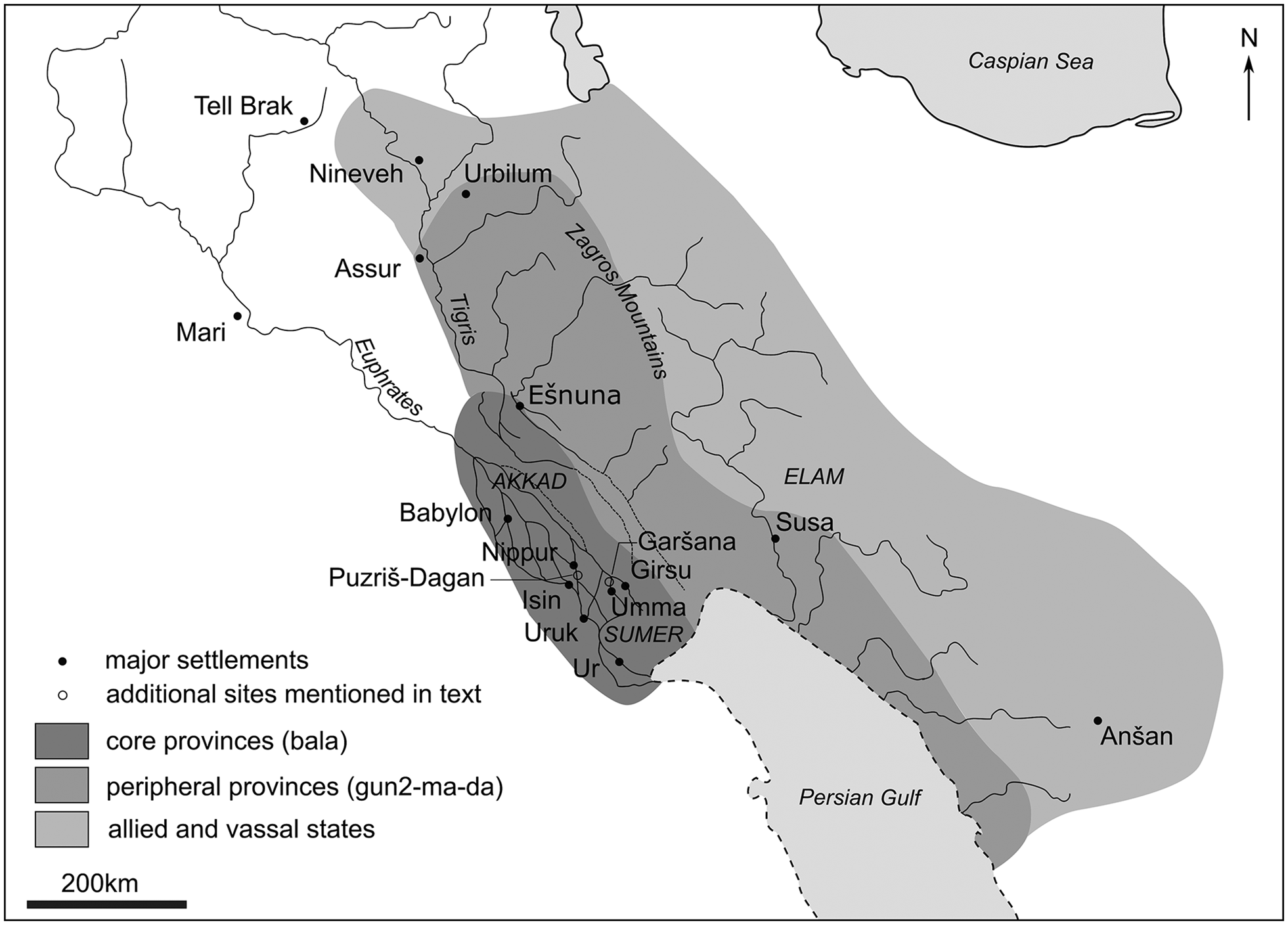

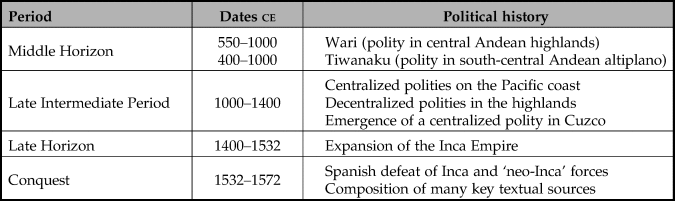

The Inca Empire was the largest and most transformative state project in the preconquest Americas (Fig. 2). Beginning around ce 1400, it expanded from a regional polity in the Cuzco valleys to an empire integrating hundreds of political communities from the intensive agriculturalists of the Chimú Empire on the Peruvian north coast to the fisher-foragers and hunter-horticulturalists of central Chile and Argentina (Table 2; Alconini & Covey Reference Alconini and Covey2018; D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy2015). While there were important ecological differences across this vast area, the preceding millennia of mobility and exchange had also ensured that a broad suite of animals were already exploited across much of western South America: domesticated camelids (llama and alpaca), dogs, guinea pigs and ducks, as well as wild camelids (guanaco and vicuña), deer, vizcachas, fish, shellfish and birds (Capriles & Tripcevich Reference Capriles and Tripcevich2016; Stahl Reference Stahl, Silverman and Isbell2008).

Figure 2. Map of the Inca Empire. (After D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy2015, figure 1.1.)

Table 2. Chronology of the central Andes.

The upper levels of imperial administration were organized territorially, with over 80 provincial governorships grouped into the four sectors that constituted the Inca empire of Tawantinsuyu. Beneath these levels, Inca subjects were ideally organized decimally with nested units up to 10,000 members, although such a fundamental reorganization of socio-political hierarchies seems to have been attempted only in the core provinces closer to Cuzco (D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy2015, 354–6). This administrative structure oversaw a political economy that can broadly be described as tributary, with goods and services due to the state and temple systems via corvée obligations (Kolata Reference Kolata2013, 144–5; Murra Reference Murra1968). In addition to mobilizing corvée labour for state projects of production and infrastructural expansion, the Inca state relocated entire communities of labourers. These activities were coordinated by the administrative hierarchy's accountants via the quipu record-keeping system (Lechtman Reference Lechtman, Henderson and Netherly1993).

In parallel with the Ur III state, comparative analyses have tended to see the Inca as a particularly centralized form of early absolutist state, with strong top-down interventions that sought (often successfully) to reorganize Andean political economies substantially (e.g. Kolata Reference Kolata2013). Others have complicated this picture, arguing for the agency of intermediate (non-Inca) elites (Malpass & Alconini Reference Malpass and Alconini2010) and spatially heterogeneous patterns of selectively intense rule (Williams & D'Altroy Reference Williams and D'Altroy1998).

Finance

Andean economies under Inca hegemony can be provisionally understood as comprising four main divisions: the administrative state, the shrine system (including the temple of the Sun), the royal estates and subject communities (with resources held at the household and supra-household levels) (D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy2015; although see Moore Reference Moore1958). The agricultural sector was central in shaping provincial strategies across the empire: through the appropriation of land, the reorganization of the labour force through mit'a corvée obligations, and investment in terracing and storage facilities, the state was able to generate and manage an unprecedented surplus of maize and tubers (D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy2015; Kolata Reference Kolata2013; Kosiba Reference Kosiba, Alconini and Covey2018).

Pastoralism formed a second important sector of the Inca economy. Colonial textual sources have provided major insights into the institutions of livestock management in the Inca political economy (Flores Ochoa Reference Flores Ochoa1970; Murra Reference Murra, Leeds and Vayda1966; Reference Murra1975). According to these texts, livestock and pastures were appropriated from conquered communities and recategorized (in parallel with agricultural lands) along the tripartite divisions of state, temple and community properties (Cobo Reference Cobo and Hamilton1990, 211–16). In addition, all wild camelids were claimed as property of the temple of the Sun.

The bureaucratic state and religious institutions raised camelids in domain herds, with colonial sources suggesting that these herds were sometimes substantially larger than those belonging to households and communities (Murra Reference Murra, Leeds and Vayda1966). In addition, there were ‘private’ estate herds that appear to have existed as part of royal domains alongside the bureaucratic state (Quave Reference Quave, Alconini and Alan Covey2018). The positions of specialized herders (llamacamayocs) and hunters were also redefined and their efforts to maximize production through new forms of herd management were supervised by the state's quipu-based bureaucracy (Flannery et al. Reference Flannery, Marcus and Reynolds1989, 107–13).

Despite these textual accounts, the limited visibility of pastoralist landscapes has tended to diminish the salience of the sector in modern archaeological syntheses (although see Nielsen Reference Nielsen2009). How did pastoralism fit into the broader Inca political economic order? D'Altroy and Earle's (Reference D'Altroy and Earle1985) influential model of staple versus wealth finance in Inca and other ‘archaic states’ leaves livestock in a liminal position. Livestock formed a clear element of staple finance in the original model: as ‘subsistence goods’ produced by agropastoralist households, they could be mobilized to provision state personnel (D'Altroy & Earle Reference D'Altroy and Earle1985, 188).

But camelids were also the source of both primary and secondary products in ways that remained unaccounted for and point towards their much more central role in translations between staple and wealth spheres. Both as live animals with low rates of reproduction and through a range of primary and secondary products (notably meat, fibre and long-distance transportation), camelids served as a major mode of value accumulation and storage. Camelids (domesticated and wild) provided much of the raw materials to fashion fine cloth, the Inca wealth good par excellence (Lechtman Reference Lechtman, Henderson and Netherly1993). D'Altroy and Earle (Reference D'Altroy and Earle1985, 195–6) included textile production in their model, seeing it as a point of articulation between staple and wealth finance as mediated by the labour of attached craft specialists. However, camelids not only supplied the means of production for the creation of wealth; they also represented wealth in themselves. Recognizing this allows us to consider the multiple roles played by camelids in staple–wealth conversion — both directly via foddering and indirectly via the costs of camelid specialists.

In some cases, state and shrine herds were tended via labour tribute from commoners (D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy2015; Kolata Reference Kolata2013). In other cases, particularly on large state farms and royal estates, llamacamayoc labour was provided by yanacona [personal retainer] and mitmacona [resettled community] herding specialists (Gyarmati & Varga Reference Gyarmati and Varga1999; Quave Reference Quave, Alconini and Alan Covey2018). Zooarchaeological evidence suggests that the Inca state used this labour to intensify specialized forms of animal husbandry, with camelid age profiles in both the central and southern Andes suggesting broad shifts towards a greater emphasis on fibre and transport as secondary products (e.g. Madero Reference Madero1994; Sandefur Reference Sandefur, D'Altroy and Hastorf2001). In some areas, centralized corrals provide additional evidence for pastoralist intensification and centralized herd management (e.g. Makowski et al. Reference Makowski, Córdova, Habetler and Lizárraga2005).

Political subjectivity

The accumulation and distribution of animal wealth intersected with the making of new political categories that sought to redefine the place of human and non-human subjects. Through their roles in state finance, animals were important in the making of imperial subjectivities (cf. Kolata Reference Kolata2013; Kosiba Reference Kosiba, Alconini and Covey2018) as communities and individuals were incorporated into new relationships with the Inca state and its intermediaries. Some of these relationships rested upon social classes that existed prior to the Inca expansion (e.g. hereditary lords and commoners), while others entailed the formation of new kinds of subjects (e.g. retainer classes such as the yanacona and new elite leaders in contexts of low prior social hierarchy).

Camelid herds were one of the major resources that the Inca alienated from subject communities. While the state fully expropriated community herds in some cases (e.g. during expansion into the Titicaca Basin: Murra Reference Murra, Leeds and Vayda1966), it seems this expropriation was often nominal, involving little change to everyday management. Nevertheless, the Inca used this strategy to earmark a portion of the camelid herds and/or their products for the state and temple domains (Kolata Reference Kolata2013; Moore Reference Moore1958). If, as some modern ethnographic accounts suggest, camelids were understood as members of deeply entwined multi-species kin groups (ayllus: Flannery et al. Reference Flannery, Marcus and Reynolds1989, 37), such interventions into community herds had the potential to reshape local ontological understandings of relatedness and obligation at an intimate level.

Appropriated livestock also played further roles in subject formation through their circulation in state practices of incorporative exchange and consumption. Camelid herds and camelid-fibre cloth were instruments of coercive gifting to the provincial elite, forming a central feature of Inca prestational politics (Kolata Reference Kolata2013). Camelids’ mobility and value (reflecting labour investment in husbandry) were qualities that made livestock gifts so useful to the state and potent to their receivers. Archaeologically, we can see these strategies through state-oriented camelid feasting (e.g. Knudson et al. Reference Knudson, Gardella and Yaeger2012; Miyano Reference Miyano2021) and, perhaps, the extension of camelid pastoralism into new regions during the Inca expansion (e.g. Troncoso Reference Troncoso2012).

A second intersection between animals, state finance and the making of new imperial subjects lay within Inca bureaucracy. Just as censuses quantified the empire's human subjects, so the state and religious herds were enumerated in counts every November (D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy2015, 356–8; Molina [1575] Reference Molina, Bauer, Smith-Oka and Cantarutti2011, 65). Indeed, in some regions, human labourers and camelids were the first and most important tributary categories to be counted (Murra Reference Murra1975).

Beyond enumeration, there are additional parallels between the Inca bureaucratization of pastoralism and the appropriation of surplus labour through new social categories that broke with existing modes of community-based labour mobilization (Murra Reference Murra1968; Rowe Reference Rowe, Rosaldo, Collier and Wirth1982). The alienation of camelids from their local communities, their segregation by sex and colour and the extraction of value from them have suggestive parallels with, for instance, the acllacuna [cloistered women dedicated to specialized labour for the state]. As with some of the state herds, women designated as acllas were relocated from their home communities and housed in special enclosures where (among other things) they processed camelid fibre, with some of the women subsequently selected for high-value sacrifices (Turner & Hewitt Reference Turner, Hewitt, Alconini and Covey2018, 267).

Violence

Camelids were central to Cuzco's ability to project force across the length of the Andes. In addition to providing logistical support to the Inca's armies, large caravans provided the possibility of meat on the hoof (D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy1992, 81–93; Murra Reference Murra, Leeds and Vayda1966). This ability to provide transportation and subsistence would have been vital in many of the low-productivity Andean landscapes where living off the land would have been difficult even for relatively small armies. Indeed, the capture of the massive Titicaca Basin herds in the early years of expansion may have provided an important stimulus to the Inca war machine, ultimately enabling the imperial breakout from the central and south-central highlands.

Animals were also at the centre of the state's displays of ritual violence. Along with human sacrifice and the burning of large quantities of high-value cloth, the large-scale killing of animals formed a central part of the Inca ritual economy (Kaulicke Reference Kaulicke, Cerrón-Palomino and Hernández Astete2021, 113). Such sacrificial offerings functioned as conspicuous forms of wealth destruction and may have drawn primarily on domain herds. Cobo ([1653] Reference Cobo and Hamilton1990, 126–50) enumerates the sacrifice of at least 1500 camelids in Cuzco's yearly ritual cycle, while Betanzos ([1557] Reference Betanzos, Hamilton and Buchanan1996, 136) suggests that 5000 camelids might be slaughtered upon the death of the Inca ruler.

However, these rituals should not be reduced to their financial cost alone. As is clear from descriptions (e.g. Molina [1575] Reference Molina, Bauer, Smith-Oka and Cantarutti2011, 41) of choreographed processions, the infliction of pain, multiple forms of killing and the post-mortem manipulation and immolation of flesh and blood, camelids were constitutive elements in violent spectacles. On display was the state's ability to intervene in the production of different forms of value and even personhood.

The figure of the caparisoned sacred llama (raymi napa: Molina [1575] Reference Molina, Bauer, Smith-Oka and Cantarutti2011, 56–61), substituting for the person of the Inca sovereign, stood at the other end of a spectrum and fitted within a broader Andean pastoralist conjunction of human and livestock as deeply related categories (Allen Reference Allen2002; Cagnato et al. Reference Cagnato, Goepfert, Elliott, Prieto, Verano and Dufour2021). This granting of human-like qualities to camelids took place within the deeply hierarchical context of the state's ability both to produce and destroy wealth: just as qualities of personhood and status could be extended to non-humans, so they could be removed through political acts of subjugation and the sacrificial destruction of both wealth-in-animals and wealth-in-people (cf. Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2017).

Territorial integration

Animals—through camelid caravanning—also formed the basis for the long-distance integration of the fractured Andean landscape into a coherent political territory. Just as camelids had played important roles in previous periods of heightened inter-regional connectivity during the Early and Middle Horizons (Tomczyk et al. Reference Tomczyk, Giersz, Sołtysiak, Kamenov and Krigbaum2019; Weber Reference Weber2019), so they helped shape the spatiality of Inca hegemony.

Andean landscapes of mobility were reshaped and reclassified to facilitate state movement of resources and people: the state integrated pre-existing trail systems into a formalized royal road network (capac ñan) of highways, bridges and waystations ostensibly restricted to official state use. While this network has fruitfully been understood in terms of its roles in military logistics (D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy1992) and the materialization of imperial ideology (DeMarrais et al. Reference DeMarrais, Castillo and Earle1996), it is worth highlighting its role as the infrastructure for animal-based mobility. Archaeological evidence for the massive flow of animals can be found at the waystations (tambos) along the capac ñan, many of which had significant corral space dedicated to the sheltering and provisioning of camelids (Casaverde Rios & López Vargas Reference Rios, & S and Vargas2013; Hyslop Reference Hyslop1984, 291).

While not all scholars have seen a central role for long-distance caravanning in the Inca period, instead arguing for the primacy of human porterage (D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy1992; D'Altroy & Earle Reference D'Altroy and Earle1985; Murra Reference Murra, Leeds and Vayda1966), camelid caravans clearly did supply distant communities with staples such as maize and dried fish (Aland Reference Aland, Alconini and Covey2018; Gyarmati & Varga Reference Gyarmati and Varga1999). Such regional and long-distance connections enabled a broad range of state projects across the Andes, from the provisioning of administrative centres in strategic yet unproductive highland locations (e.g. Pumpu in central Peru at 4090 masl) to the support of mining and ritual sites located in even more hostile locales (e.g. Abra de Minas in northwestern Argentina at 4240 masl). In this sense, the ‘selectively intense’ patchwork of Inca hegemony that confounds simple core-periphery models—particularly in the provinces of Collasuyu located far to the south of Cuzco—was deeply reliant on long-distance camelid mobility.

Animals outside the state

Textual sources continue to dominate the literature on animals and the Inca state, often fostering a top-down, Cuzco-centric perspective. The colonial archive contains clear statements about an Inca imperial order radically reshaping the management and distribution of animals (domestic and wild) and regulating the movement of humans and animals along formalized road networks (D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy2015, 370). Yet we need to remember that these were political claims about how the imperial economy ought to work rather than how it necessarily worked out in practice (Covey Reference Covey and Shimada2015; Garrido & Salazar Reference Garrido and Salazar2017).

For instance, synthetic accounts of Inca foodways often rely on colonial texts to infer a relative lack of meat (particularly camelid meat) in commoner diets (e.g. Jennings & Duke Reference Jennings, Duke, Alconini and Covey2018). But did the state try to regulate everyday foodways in the provinces? Or did these statements, instead, relate to specific contexts of state-hosted diacritical feasting? While zooarchaeological evidence for commoner diets remains to be synthesized across the region, some faunal assemblages from the central Andes suggest a rather less regulated picture, with camelid meat consumption both higher and more homogenous across households than a top-down model of restriction would imply (Quave Reference Quave, Alconini and Alan Covey2018; Sandefur Reference Sandefur, D'Altroy and Hastorf2001).

Other animals were potentially even more difficult to incorporate within the state's political economic apparatus. Guinea-pig production persisted outside the reach of the state, providing a household-level complement to local subsistence and ritual economies with few infrastructural or labour costs (Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2008). And despite Inca claims to the contrary, hunting and fishing would have been particularly difficult to oversee fully (Aland Reference Aland, Alconini and Covey2018), offering communities access to a range of what might even be thought of as ‘escape animals’ (compare Scott Reference Scott2009, 199–201).

Discussion

The Ur III and Inca case studies demonstrate the multiple roles played by livestock as sources of social power. Building on Mann's framework, the foregoing analysis centres on how livestock circulated and accumulated in the political economy of the early state, while tracing their articulations with the exercise of violence, territorial integration and projects of subject formation. Both cases were characterized by particularly high degrees of political and economic centralization, exceptional levels of labour mobilization and large royal and temple domains holding a significant portion of available land and livestock resources. Thus, we stress caution in drawing over-generalized conclusions about the roles played by animals within the diverse economic forms of the premodern state (Earle Reference Earle2002; Hirth Reference Hirth2020). Nevertheless, the parallels between our case studies and other state political economies highlight important possibilities for further comparative research.

Certain types of domesticates—large mammals like camelids, cattle, equids and caprines—repeatedly emerged as attractive resources for state finance projects. Some, like sheep and camelids, facilitated the conversion of staple surplus or pastureland into wealth in the form of primary and secondary products. Others, like cattle and equids, served as labour multipliers in agriculture and transportation. Animals were also deeply embedded within culturally specific regimes of value. But we suspect the real importance of livestock in political economies was their flexibility: at different moments, animals could be sources of fibre, on-the-hoof provisions, sacrifices, or highly valued gifts. In Marxian terms, animals appear at different moments as subjects of labour, as instruments of labour and as products of labour.

This capacity of certain livestock types to be flexible sources of wealth and thus serve multiple roles in premodern state finance is particularly visible in economies that focused upon a limited number of species. The Inca's heavy reliance on camelids finds a clear parallel with the roles of cattle as sources of dairy staples, meat and hides, as ritual sacrifices and as pack animals in the southern African Iron Age. During its nineteenth-century emergence, for instance, the rapidly expanding Zulu state made the flow of cattle one of its primary concerns, taxing vassals in cattle, seeking cattle as war booty and granting gifts of captured cattle to loyal soldiers and to establish patron–client relationships (Chanaiwa Reference Chanaiwa1980).

Part of this flexibility offered by animals as wealth was predicated on their mobility. This mobility enabled territorially expansive states to rely on animals as payment of taxes or tribute from distant regions to the imperial core (recall the Ur III gun2-ma-da tax paid by peripheral provinces). Hirth (Reference Hirth2020, 177–88) has noted the significant costs of transporting tribute and taxes in imperial settings, which tended to prioritize wealth finance (and in some cases, commodity and representative monies) above staple finance strategies over the long term. Animals provided a unique solution to transportation costs. Additionally, foraging species offered particular advantages: caprines, cattle and camelids could forage as they moved across the arid grasslands of Mesopotamia and the Andean highlands. The mobility of animals as wealth thus made them ideal assets for large-scale taxation and redistribution systems (as in the mobilization of pigs across the Italian peninsula to provision the Late Roman imperial pork dole: Barnish Reference Barnish1987), while often creating new demands for infrastructural investment.

In parallel to the centripetal movement of animal finance into early state cores, animal mobility was also central to the centrifugal projection of military and infrastructural power into the provinces. Particularly in the Inca case, there are indications of growing reliance on the logistical support offered by large domesticated mammals. The emergence of ‘animalized’ war machines was crucial to the integration of many other early states, with a key example provided by the combined rise of horse-mounted warfare and defensive wall systems during the Warring States Period which set the stage for the subsequent unification of China under the Qin (Shelach-Lavi et al. Reference Shelach-Lavi, Jaffe and Bar-Oz2021).

Territorial integration within expansionist states was undergirded in many instances by the construction of road networks, waystations and animal pens. Meanwhile, the consequent escalation in political economic scale led to information management concerns and the deployment of new techniques of bureaucratic quantification (e.g. the booms in quipu and tablet production in the Inca and Ur III cases), with a strong emphasis on tracking the production and circulation of animal wealth. The quantification of animal economies, in turn, fostered novel understandings of value, hierarchy and the human–animal relationship.

Herd animals, notably camelids in the Andes and caprines in Sumer, were repeatedly deployed as powerful new metaphors for human subjectivity. While the twentieth and twenty-first centuries provide examples of animals as central elements in discourses of dehumanization, we highlight the much deeper genealogies of these metaphors in the history of the state. In his studies of animal domestication and herding in the ancient Near East, Tani (Reference Tani2017, 110–14) has argued that the relationships of property, control and domination over herd animals provided a new hierarchical schema of subordinated life. In combination with bureaucratic techniques, these hierarchies opened up new possibilities for states to categorize, dehumanize (and sometimes specifically ‘animalize’) their subjects, especially labourers. Particularly in the Ur III case, this logic of the ‘bureaucratized herd’ formed a powerful part of the ideological apparatus that some early state institutions deployed to articulate and naturalize inequalities. But human–livestock metaphors have a double nature: as the Inca case demonstrates, the selective personification of animals could also form an important arena for state politics.

These deployments of human–animal categories also naturalized relationships of political supremacy. The herder–herd relationship, for instance, could be appropriated to naturalize the power of the ruler. Indeed, the concept of the sovereign as shepherd was frequently used throughout Near Eastern and Mediterranean elite discourses, including in the Biblical and Homeric texts, declining in usage only in the late first millennium bce (Varhaug Reference Varhaug2019). In other cases, there was greater emphasis on the violent constitution of rulership through identification of the ruler as hunter (Allsen Reference Allsen2006) or even as predator (Lau Reference Lau and Staller2021).

The material and the symbolic came together perhaps most spectacularly in those instances where early states managed ritual economies (McAnany & Wells Reference McAnany, Wells, Wells and McAnany2008) based on the accumulation and destruction of animal vitality. The killing of large numbers of animals is an element of statecraft that appears repeatedly across early state societies, whether through feasting (more common in the Ur III case) or through dramatic immolation (as in many Inca state rituals). In some cases—as with the sacrifice of cattle at the late Shang capital of Anyang (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Jaffe, Kim, Sturm and Jaang2021)—there was a reliance on the pastoralist sector to finance these state performances, while in other cases—for instance, the capture and sacrifice of wild predators for Mesoamerican states like Teotihuacan and Copan (Sugiyama et al. Reference Sugiyama, Fash and France2018)—such rituals relied upon formalized networks of hunting and long-distance trade. As the ritualized killing of wild animals outside the state's urban centres, hunting formed an additional mode for mixing political performance with political economy, particularly through its enactment of elite claims over particular species and/or rural spaces (Allsen Reference Allsen2006).

Finally, there are several ways that animal economies may have acted in opposition to the exercise of early state power. The spatially extensive nature of many animal production systems meant that they were often less amenable to the effective exercise of state surveillance and accounting than other sectors (e.g. crop production, mineral extraction and crafting). While we recognize the difficulties in detecting the frictions in formal livestock economies (from foot-dragging to the delivery of substandard animals to the skimming of herd production), these would have been important contradictions within early state political economies. In addition, animals also often formed important parts of informal sectors that existed largely beyond the gaze of the state (and, by extension, the textual archive). In our case studies, the production or exploitation of pigs in Mesopotamia and guinea pigs, deer, and marine animals in the Andes all largely fell outside the formal sectors of the state economy. The methodological implications here are basic but important: with some exceptions (e.g. texts documenting elite household property management (Owen & Mayr Reference Owen, Lion and Michel2006)), texts only document formal sectors, with zooarchaeological evidence of informal practices forming a necessary complement to text-based studies of early state economies (Price et al. Reference Price, Grossman and Paulette2017; Pruß & Sallaberger Reference Pruß and Sallaberger2004).

Beyond these ‘everyday forms of resistance’ (Scott Reference Scott1985), there are also ways that some types of livestock production could enable people actively to rebel against or escape from the state. Mobile pastoralists’ ability to resist the state is an oft-repeated idea with an intellectual history stretching back to Ibn Khaldun and Exodus, although one that certainly needs to be evaluated carefully (Arbuckle & Hammer Reference Arbuckle and Hammer2019; Honeychurch Reference Honeychurch2014). As the two case studies suggest, however, pastoralist economies were often partly incorporated into state institutions—rather than existing in simple subservience or opposition to these early states, animal economies provided a paradoxical set of both opportunities for and limitations upon the effective exercise of state power.

Although traditional models of premodern political economies have emphasized labour, land and water as the fundamental resources accumulated and managed by early state administrations, livestock formed a unique kind of wealth that merits greater theoretical and empirical attention. The specific qualities of animals—including their mobility, animacy and overall flexibility—meant they often connected across economic sectors and across spatial scales in unique and powerful ways. As such, animals could strengthen state institutions and integrate territories, while also offering ways for non-state actors to undermine state power at local and household levels. The recognition of animals as key resources in early state economies—through a combination of textual and zooarchaeological analyses—offers the possibility of better understanding early state institutions as heterogenous, both powerful and existing in symbiosis with the informal activities of subject communities and households.