Introduction

Readymade is a term from the world of modern art theory and practice. It describes art created from existing fully formed, usually modified objects that are not considered materials from which art is made, often because they already have a non-art function. The main argument of this paper is that certain Palaeolithic artefacts may be considered to have been made following similar concepts and techniques, in order to preserve a mnemonic value (their visual memory, that of their manufactures, as well as that of their itineraries). I present a theoretical framework for this claim as well as a case study from the Palaeolithic period.

Prehistoric findings have been linked to the world of art (see Lascaux and ‘Venus of Willendorf’ in The Oxford Dictionary of Art; Chilvers Reference Chilvers2004a,Reference Chilversb), but the following question has not yet been developed nor explored: were ideas and processes known today from the world of modern art theory applied by prehistoric populations in a manner that, while not itself a mode of art, should be considered a mode of behaviour and existence? I do not imply that these prehistoric Readymade items were made with the intention to create art (Readymade art) as we term it today. Rather, I contend that the concepts and techniques behind the creation of Readymade objects according to modern art theory were practised as part of the manner in which prehistoric people perceived and interacted with their world.

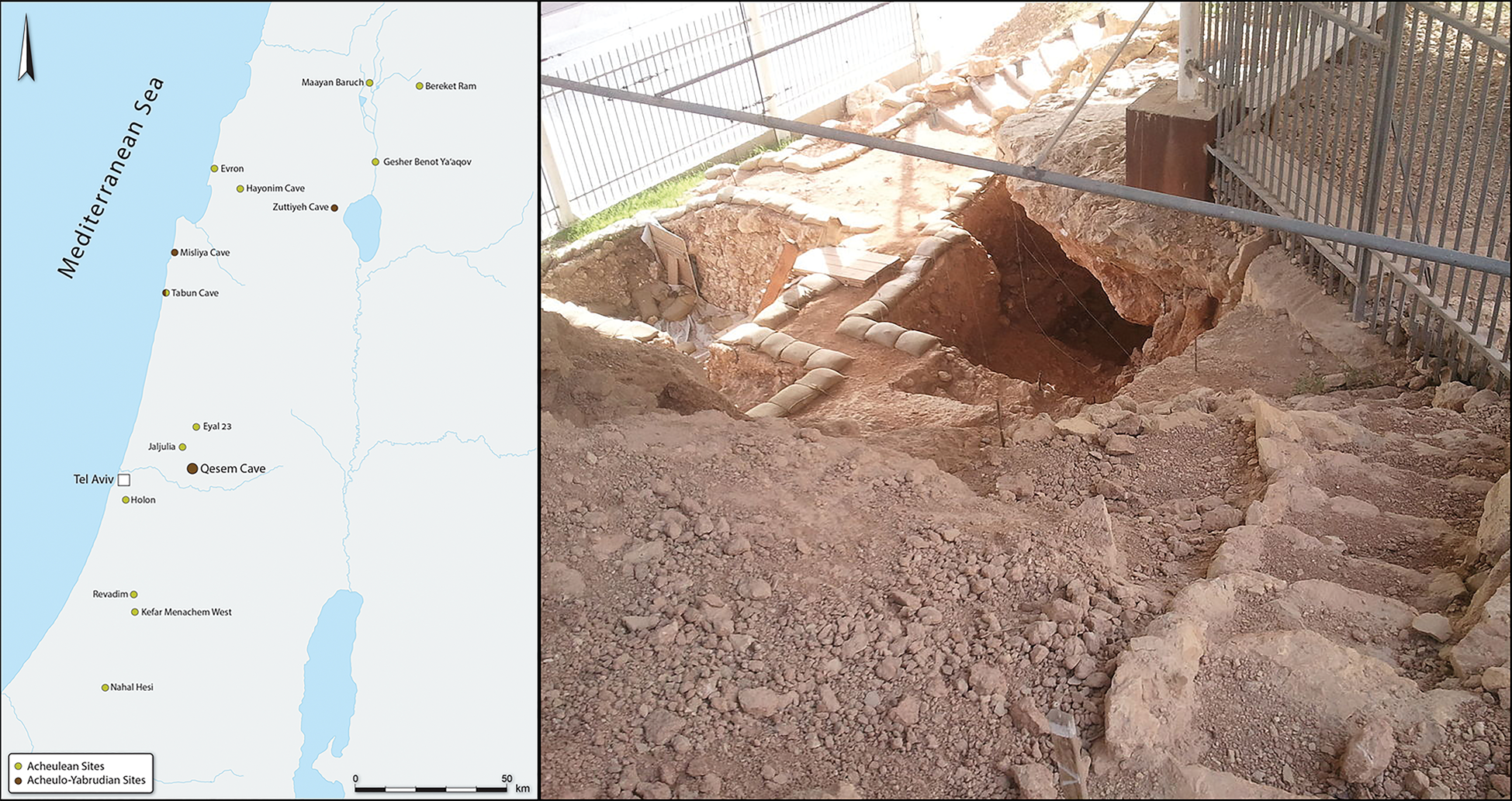

The case study will focus on the phenomenon of ‘double patina’ (or post-patination flaked items; PPF items) from the Late Lower Palaeolithic site of Qesem Cave, Israel, assigned to the Acheulo-Yabrudian Cultural-Complex (AYCC) and dated to about 420,000–200,000 bp. I focus on specific items: PPF scrapers made on fully patinated ‘old’ modified items. PPF scrapers are items that were made by earlier groups, abandoned, covered in patina and then later picked up in the vicinity of the site and brought to the cave to be recycled into scrapers. As Figure 1 shows, the morphology, colour and old modifications of the patinated surfaces were maintained and fully preserved on the ‘new’ recycled end-item, and the new post-patina modifications consist only of reshaping the working edge of the scraper.

Figure 1. (a) Post-patination flaked scraper from Qesem Cave that preserves the morphology and colours of the fully patinated ‘older’ blank: (b) Frontal view of the dorsal face of the recycled scraper; dashed line shows the patinated blank's original outline prior to recycling.

I claim that these items, characterized by unique and prominent features, are readymade objects; recycled according to readymade techniques, and following readymade concepts, in order to preserve their memory onwards in a specific manner. I argue that the intentionally preserved surfaces of the ‘old’ item, a result of readymade processes, makes it possible to comprehend the conceptual characteristics of the recycled item in new ways. I suggest that the selection and slight modification of these items, perhaps characterized and conceived of as ‘gifts from the ancestors’, reflect a Palaeolithic worldview that connects human and non-human agents, as well as the present and the past. As a result of readymade processes, these recycled scrapers served both as functional tools and medium tools that allowed their users to reconnect with ancestors—both human and non-human—as well as with familiar landscape features, acting as mnemonic objects. I present a case study of these tools along with theoretical background to show how they can be considered manifestations of readymade concepts and techniques.

Qesem Cave

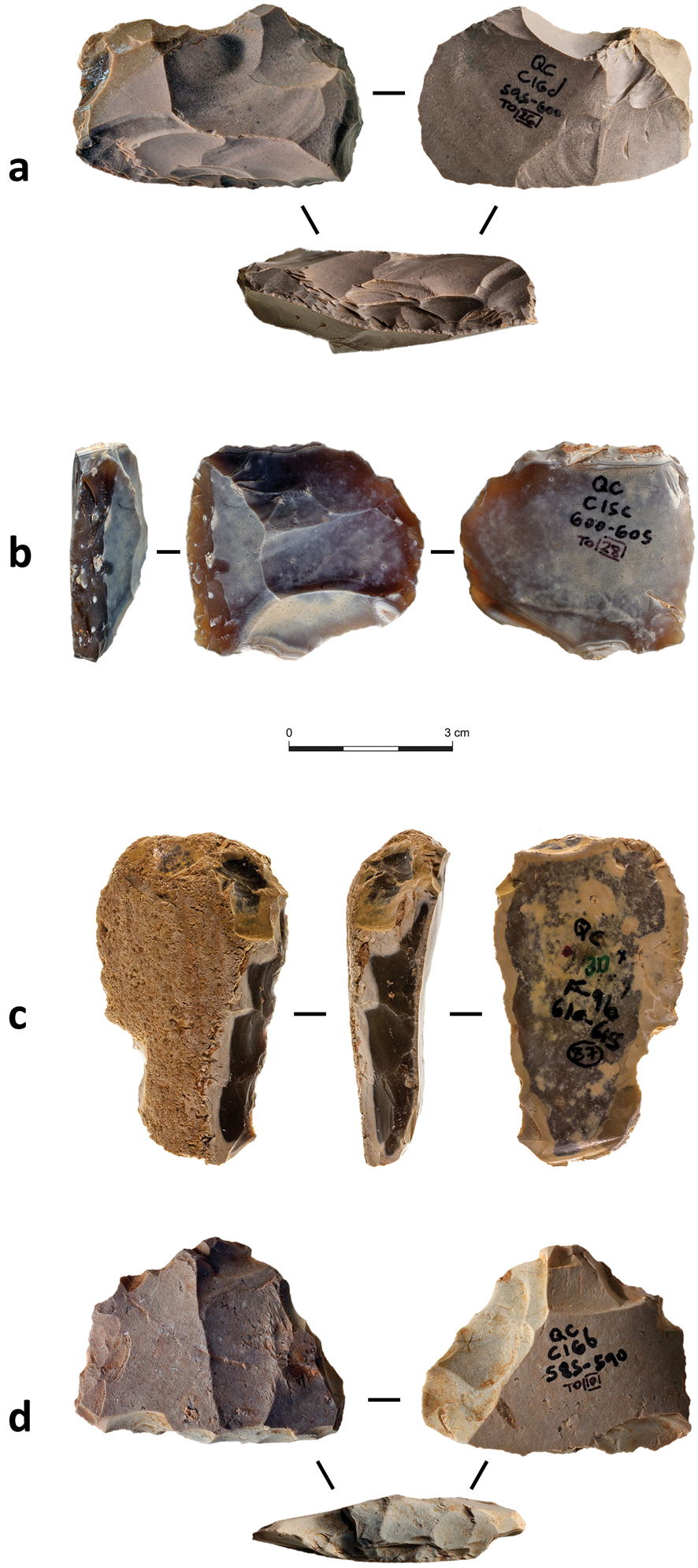

Qesem Cave is dated to 420,000–200,000 bp and situated about 12 km east of the Mediterranean coast of Israel. Ongoing excavations have exposed a stratigraphic sequence of more than 11 m of deposits. Bedrock has not yet been reached (Fig. 2). No younger or older Palaeolithic occupations were discovered at the site, thus implying a single cultural complex, albeit a long temporal span for the AYCC (Barkai et al. Reference Barkai, Rosell, Blasco and Gopher2017; Reference Barkai, Blasco, Rosell, Gopher, Pope, McNab and Gamble2018 and references; Gopher et al. Reference Gopher, Parush, Assaf and Barkai2016).

Figure 2. Location map and an inside look at Qesem Cave.

The rich and well-preserved lithic assemblages represent the complete chaîne opératoire for laminar production and fragmented chains for other trajectories (scrapers, stone balls, bifaces). Most lithic assemblages were assigned to the Amudian blade industry (laminar production), apart from several assemblages in which scrapers (most of which are Quina and demi-Quina) dominated the shaped items (22–51 per cent of the tools) and are thus assigned to the Yabrudian industry. In terms of general field relations and chronometric resolution, the two industries seem to be contemporaneous and part of a single technological repertoire.

Lithic recycling is another technological trajectory in evidence at the site in all archaeological contexts. A technological analysis reconstructed several modes of recycling at Qesem (Parush et al. Reference Parush, Assaf, Slon, Gopher and Barkai2015): handaxes recycled to cores, recycled scrapers, the production of small blades and flakes with sharp edges from a ‘parent’ flake or blade (core-on-flake), and the collection and recycling of patinated flaked items exhibiting post-patina modifications. The latter will be the focus of this paper (see Efrati et al. Reference Efrati, Parush, Ackerfeld, Gopher and Barkai2019; Lemorini et al. Reference Lemorini, Bourguignon, Zupancich, Gopher and Barkai2016; Parush et al. Reference Parush, Assaf, Slon, Gopher and Barkai2015; Venditti Reference Venditti2019 and references).

Micro-vertebrate and avifauna analyses at Qesem Cave picture the surroundings of the cave as a mosaic of different localities, from open paleo-environment localities with sparse vegetation to shrubland, Mediterranean forest, rocky areas and riverbanks (Maul et al. Reference Maul, Smith, Barkai, Barash, Karkanas, Shahack-Gross and Gopher2011; Sánchez-Marco et al. Reference Sánchez-Marco, Blasco, Rosell, Gopher and Barkai2016). Qesem Cave also provides a good example of a site whose surroundings are rich in lithic sources; 41 such localities have been identified around the cave (Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Agam, Barkai and Gopher2016). Lithic materials at Qesem Cave were obtained by both surface collecting and sub-surface extraction from secondary and primary sources, where a large variety of flint types were collected and used (Boaretto et al. Reference Boaretto, Barkai, Gopher, Berna, Kubik and Weiner2009; Lemorini et al. Reference Lemorini, Bourguignon, Zupancich, Gopher and Barkai2016; Verri et al. Reference Verri, Barkai and Bordeanu2004; Reference Verri, Barkai and Gopher2005).

Aside from unmodified flint materials, ‘old’ flaked patinated flint items were also surface-collected for recycling (Efrati et al. Reference Efrati, Parush, Ackerfeld, Gopher and Barkai2019; Lemorini et al. Reference Lemorini, Bourguignon, Zupancich, Gopher and Barkai2016), as were ‘old’ handaxes and spheroids. All are believed to have been collected from older archaeological Acheulian sites (Agam et al. Reference Agam, Wilson, Gopher and Barkai2019; Barkai et al. Reference Barkai, Gopher, Solodenko and Lemorini2013; Barkai & Gopher Reference Barkai and Gopher2016). Thus, it is well evidenced that the inhabitants of Qesem Cave were highly acquainted with the different resources available both in the cave area and farther afield, and were able to locate and transport large quantities of rock, animal body parts, firewood and most probably other essentials to the cave (Barkai et al. Reference Barkai, Blasco, Rosell, Gopher, Pope, McNab and Gamble2018).

Post-patinated flaked items (‘double patina’)

The presence of patinated flaked items that were then recycled into new tools was brought to our attention during fieldwork and material analysis. These items appear in all assemblages and layers at Qesem Cave, together with items made from fresh, unpatinated flint. The patina at Qesem Cave varies in type, colour and texture. The layer of patina also differs in colour and texture from the natural colour of the flint (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Post-patination flaked items from Qesem Cave.

The subject of flint patination, and the patination of other rock artefacts, started at the end of the nineteenth century, with the work of Judd (Reference Judd1887). Since then, studies on flint and rock patina vary in terms of subject and terminology (Nadel & Gordon Reference Nadel and Gordon1993; Purdy & Clark Reference Purdy and Clark1987). Patina has often been studied in an attempt to distinguish mixed assemblages, or to understand colours and types of patina in relation to conditions of site formation and post-depositional processes, as well as environmental conditions (Burroni et al. Reference Burroni, Donahue, Pollard and Mussi2002; Curwen Reference Curwen1940; Dorn Reference Dorn1988; Goodwin Reference Goodwin1960; Howard Reference Howard1999; Reference Howard2002; Hurst & Kelly Reference Hurst and Kelly1961; Purdy & Clark Reference Purdy and Clark1987; Rottländer Reference Rottländer1975; Schmalz Reference Schmalz1960). In other studies, it became part of an attempt to document evidence for lithic recycling (Amick Reference Amick2015; Baena Preysler et al. Reference Baena Preysler, Ortiz Nieto-Márquez, Torres Navas and Bárez Cueto2015; Belfer-Cohen & Bar-Yosef Reference Belfer-Cohen and Bar-Yosef2015; McNutt Reference McNutt and Goren-Inbar1990; Peresani et al. Reference Peresani, Boldrin and Pasetti2015; Romagnoli Reference Romagnoli2015).

The phenomenon of recycled items made from ‘older’ patinated items that were collected and modified for reuse is prevalent at many Early to Upper Palaeolithic sites in the Levant and beyond (e.g. Agam & Barkai Reference Agam and Barkai2018; Amick Reference Amick2015; Belfer-Cohen & Bar-Yosef Reference Belfer-Cohen and Bar-Yosef2015; Corchón Rodríguez Reference Corchón Rodríguez1994; Efrati et al. Reference Efrati, Parush, Ackerfeld, Gopher and Barkai2019; Iovita et al. Reference Iovita, Fitzsimmons, Dobos, Hambach, Hilgers and Zander2012; Peresani et al. Reference Peresani, Boldrin and Pasetti2015; Romagnoli Reference Romagnoli2015; Shimelmitz Reference Shimelmitz2015; Vaquero Reference Vaquero2011), as well as in sites dated to later periods (e.g. Galili Reference Galili1987; Galili & Weinstein-Evron Reference Galili and Weinstein-Evron1985; Gopher Reference Gopher1990; Hole Reference Hole1959; Kuijt & Russell Reference Kuijt and Russell1993; Makkay Reference Makkay and Bökönyi1992; McDonald Reference McDonald1991; Parush et al. Reference Parush, Yerkes, Efrati, Barkai and Gopher2018; Vaquero Reference Vaquero2011). Such items are often termed ‘double patina’ in prehistoric research (Amick Reference Amick2015; Goodwin Reference Goodwin1960; Vaquero Reference Vaquero2011) because the newer modified surfaces are easily distinguishable from the old ones due to colour and texture differences. Any new modification also testifies to a gap in time between the previous life-cycle of the patinated flint item and its new one. We classified patinated flaked items as items ‘that have been modified again, thus leaving newer scars in unpatinated, or less patinated, condition’ (Efrati et al. Reference Efrati, Parush, Ackerfeld, Gopher and Barkai2019; Goodwin Reference Goodwin1960, 68). These newer scars expose the natural colour of the flint, or a different kind of patina alongside old scars covered with older patina.

Following preliminary work on PPF items from Qesem Cave (Efrati et al. Reference Efrati, Parush, Ackerfeld, Gopher and Barkai2019), it is assumed that patinated flaked items were collected and brought from outside the cave to be used as lithic material for the production of ‘new’ items. Their recycling seems to have been intentional, since fresh items that do not show any sign of patination are found in abundance in the same contexts and in larger quantities. Moreover, all recycled patinated items indicate that they were selected mostly based on their knapping potential in relation to selected wanted technological trajectories used, and reflect a calculated selection of ‘old’ patinated items. Thus, it seems that specific older patinated artefacts were collected according to desired properties such as size and appearance based on different technological needs. Furthermore, the colours and textures of the recycled patinated items vary greatly. These items were probably collected from older sites in different environments and localities out of the multiple environmental areas identified in the cave's surroundings (Bradley Reference Bradley2002; Efrati et al. Reference Efrati, Parush, Ackerfeld, Gopher and Barkai2019; McDonald Reference McDonald1991; Romagnoli Reference Romagnoli2015; Vaquero Reference Vaquero2011).

It has often been suggested that flint recycling is a result of scarcity of lithic materials, which promotes a maximization of lithic resource profitability, including the collection and recycle of ‘old’ patinated flaked items (Hiscock Reference Hiscock2015). The same is argued regarding the recycling of double patinated items (Amick Reference Amick2015; Peresani et al. Reference Peresani, Boldrin and Pasetti2015; Romagnoli Reference Romagnoli2015). According to Amick (Reference Amick2015), one of the factors that seem to increase the likelihood of lithic recycling (including that of double patinated items) is scarcity in lithic sources, the value of the lithic resource and saving the costs involved in acquiring fresh material. Romagnoli (Reference Romagnoli2015) describes the economic advantages of the practice as stems from layer L in Grotta del Cavallo, Italy. According to her, the scavenging of patinated items outside the cave and their transport and use in the site suggest that this recycling trajectory demonstrates a high level of planning that stems from the need and choice to maintain economic costs related to time constraints (Romagnoli Reference Romagnoli2015, 209).

However, it seems that this was not always the case, and recycling has also been documented in areas where lithic materials were abundant (Baena Preysler et al. Reference Baena Preysler, Ortiz Nieto-Márquez, Torres Navas and Bárez Cueto2015; Parush et al. Reference Parush, Assaf, Slon, Gopher and Barkai2015; Verri et al. Reference Verri, Barkai and Bordeanu2004; Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Agam, Barkai and Gopher2016). The same can be said regarding the collection of old flaked patinated items as workable materials at Qesem Cave, which does not necessarily imply a shortage in lithic materials. Hence, this recycling of patinated items at Qesem Cave was not the result of a shortage of lithic sources but rather seems to reflect a coherent, culturally based behaviour coupled with practical needs. It is important to note that full and partial chaînes opératoires of different types of items and tools, made of fresh unpatinated flint, are present at all contexts of the cave, while recycled patinated items amount to c. 12 per cent of all assemblages, indicating a recurrent phenomenon practised in addition to the constant supply of fresh nodules and blanks produced elsewhere than the cave (Barkai et al. Reference Barkai, Blasco, Rosell, Gopher, Pope, McNab and Gamble2018; Efrati et al. Reference Efrati, Parush, Ackerfeld, Gopher and Barkai2019). Moreover, it was recently demonstrated that bifaces and shaped stone balls were also collected from older Acheulean sites in the vicinity of the cave for both practical and perceptual reasons (Agam et al. Reference Agam, Wilson, Gopher and Barkai2019; Assaf et al. Reference Assaf, Caricola and Gopher2020), suggested to be viewed as acts of appreciation towards the functional benefits of these items as well as their ancestral essence.

Thus, I suggest that the selection and collection of old patinated flaked items should be viewed in the framework of modes of ancient ecological knowledge and ecological use of resources. This set of behaviours combined necessities and cultural choices that were most probably based on world-views and perceptions, economical and functional preferences, as well as on relationships and interactions between humans and the world they lived in (objects, nature, material, animals, etc.: Arthur Reference Arthur2018; Boivin Reference Boivin2008; Boivin & Owoc Reference Boivin and Owoc2004; Conneller Reference Conneller2011; Efrati et al. Reference Efrati, Parush, Ackerfeld, Gopher and Barkai2019).

As mentioned above, Qesem Cave is dominated by scrapers. Whether recycled from patinated artefacts or not, scrapers at Qesem Cave appear in large numbers and are present in all assemblages and contexts of the cave. Use-wear and residue analysis conducted on hundreds of scrapers from the site ascribe these items to tasks related to hide working, bone working, and even plant and meat processing (Lemorini et al. Reference Lemorini, Bourguignon, Zupancich, Gopher and Barkai2016; Zupancich et al. Reference Zupancich, Nunziante-Cesaro and Blasco2016). They were probably used primarily for the processing of hides, bones and meat of fallow deer, which dominate all the faunal assemblages of Qesem Cave.

Recycled scrapers almost fully covered in patina are of interest, not because of their large number, but rather because of their outstanding appearance and their central role in the processing of different animal parts. These items appear alongside fresh-made scrapers. The recycling process did not change the item's original appearance very much and left the previous life-cycle of the item clearly visible. Thus, they are easily distinguishable from the fresh-made scrapers. The only modification is the retouching of the scraper's active edge, and in some cases a few newer removals from the old artefact's ventral face. This manner of modification fully preserves the morphology of the original patinated artefact; the varying colours, textures and patterns of the patina as well as its previous surface modifications remain visible and dominant (Figs 1 & 4). This indicates that the patinated items were selected according to preferred properties, as mentioned, following a selection that is based on their suitable characteristics for specific technological trajectories practiced at Qesem Cave, and maybe also for their colours and textures (Efrati et al. Reference Efrati, Parush, Ackerfeld, Gopher and Barkai2019; Lemorini et al. Reference Lemorini, Bourguignon, Zupancich, Gopher and Barkai2016).

Figure 4. Post-patination flaked scrapers from Qesem Cave that preserve the morphology and colours of the fully patinated ‘older’ artefact.

In light of their prominent features, I propose that recycled scrapers made on fully patinated flaked artefacts should be considered a very early example of the concept of Readymade from modern art theory. I propose that these items exhibit visual characteristics that enable argument that they were collected due to and made (recycled) according to Readymade concepts and techniques according to modern art theory.

Readymade theory

Readymade art items are common objects that have been selected and superficially altered, isolated from their original functional context and displayed as a work of art. Despite their isolation from their original context, Readymade objects still present and represent it in their new context. The term was first coined by Marcel Duchamp. One of his more famous Readymade pieces is ‘Fountain’—a urinal made of porcelain that he signed with a pseudonym and submitted to an exhibition (Chilvers & Glaves-Smith Reference Chilvers and Glaves-Smith2009; Roberts Reference Roberts2007; Reference Roberts2010).

Readymade describes the art movement which began with Duchamp's work and whose practitioners were active during the early twentieth century. However, more importantly, Readymade is also the working technique of producing an object from other existing objects. The technique itself was used before the movement and after it ceased to be active, up until today (Roberts Reference Roberts2007). As a working technique, it is integrated with other techniques and is manifested by multiple contemporary artistic groups and designers; any political or social meaning that was originally associated with the Readymade movement has largely been stripped away.

I contend that scrapers made from ‘old’ fully patinated artefacts from the Palaeolithic period are Readymade in concept as well as technique, in the same way that art from the pre- and post-Readymade movement, stripped of its social and political connotation, can nonetheless be considered conceptually and technically Readymade. My claim relates only to the stages of the working technique, to the technical aspects of producing the item from an existing object, and to any possible personal experiences the creator might undergo. I believe these stages and experiences are universal, and not particular to any historical period or place.

Instead of projecting the term Readymade into a present (or future) human history, I try to project it into the past, to the Palaeolithic period, and claim that back then Readymade and the concepts behind the creation of Readymade items were not modes of art but rather responses to how prehistoric people perceived and interacted with the world. In this prehistoric world-view, human and non-human beings (such as stones and other objects) alike were considered as persons and ‘alive’ (Alberti & Marshall Reference Alberti and Marshall2009; Arthur Reference Arthur2018).

As a response to these kinds of perceptions, I suggest that the process of Readymade was initiated in lithic technology during the Palaeolithic period in order to preserve memory visually. Under this framework (that of Palaeolithic research and lithic analysis), I term Readymade as the process and selection of specific material items, and the decision to include those in a different context than their original one. As part of that, there are two levels of Readymade processes, one in the ‘collection’ (concept) of the material, and the other in the ‘modification’ (technique) of the re-designed item. Mnemonic memory plays a role in these processes as well. In the process of ‘collection’ it is the spark within the collector that prompts the identification and collection of the item. Later, in the process of ‘modification’, mnemonic memory dictates the pattern of recycling, so as to preserve the original surface and markers of the collected item, while adding new features to it. Thus, during the process of creating a Palaeolithic Readymade object, the socio-cultural experiences and values of the time are poured into the object itself.

In his book The Past in Prehistoric Societies, Richard Bradley discusses a similar idea that is related in collecting long-forgotten old objects in prehistory and charging them with meaning long after their original one has been forgotten which, in turn, also dictates the decision on how to treat it; a logistic, purposeful decision made by the new owner:

Portable material culture may have circulated long after its production because some items had been regarded as heirlooms and others had been rediscovered after they were first deposited. That would not have been true of the ways in which people in the past modified the appearance of the land, by building earthworks or by other projects. These were always present and would have posed a problem to later generations. In fact their very survival presented several choices: they could be ignored or even destroyed, or their significance would need to be interpreted. Their physical fabric might even be renewed. This is not a simple matter of ‘continuity’, but results from strategic decisions that may have been made long after the original roles of these features had been forgotten. In principle, each excavated context provides a snapshot of one particular moment … The landscape is where different time scales intersect, and archaeologists have always accepted that. What they tend to forget is that this was equally true for people in prehistory who would also have come to terms with these traces of the past. (Bradley Reference Bradley2002, 156)

My attempts to link Palaeolithic material culture to Readymade concepts according to art theory, revealed three Readymade characteristics of the Palaeolithic items, identifiable during the process of collecting the patinated artefacts and producing the scrapers (Readymade objects) and expressed in or visible on the finished product.

First, the process of conceiving and creating a Readymade object differs from the making of a new object from scratch. In modern art, the Readymade technique is strongly connected to the idea of handcraft. The ‘inner self’ as an expressive self of the artist is no longer seen as the only truth in the world of art, and the Readymade artist is no longer seen as a ‘creator’ but also as a ‘manipulator’ of existing objects. These new dimensions dictate a different relationship between the eye and the hand that comes into play in the creation of a new object from an existing one, as well as a different thought process (Roberts Reference Roberts2007; Reference Roberts2010). In the case of the Palaeolithic scrapers, the decision to retouch and modify only a certain part of the older collected patinated artefact in order to give it a new life-phase can also be viewed in light of Readymade concepts.

Second, a Readymade object always exhibits visual interplay between presentation and representation. Instead of creating an object, or a representation of it, from scratch, the artist uses an existing object that, when presented anew, represents itself. The artist does not need to ‘persuade’ the ‘audience’ that the finished piece, or some details in it, are something else—it is exactly what it appears to be (Roberts Reference Roberts2007).

Third, being dissociated from its original context, the Readymade object incorporates both the non-artistic context and non-artistic hands of others as well as the artistic context and skills of the artist. It is a constellation of commodities as well as an artistic act. Readymade as a working technique thus establishes a mode of interaction between humans, objects and technological and technical processes (Roberts Reference Roberts2007).

A different process of conceiving and creating

The process of conceiving and creating a scraper from an existing fully patinated artefact differs from the making of a new scraper from an unmodified, newly selected, unaltered material, or a newly produced blank. This can also be seen as analogous to the concept of the Readymade. The material from which the knapper begins the process of creation is a finished product in which the morphology of the original object is to be maintained insofar as is possible, thus allowing the creator limited options for styling and reshaping. The hand and eye now become linked through the selection and arrangement of materials, forcing a shift in technical base from the techniques used for shaping an unmodified flint nodule to the organization and manipulation of an already modified flint item.

The interplay between presentation and representation

A finished scraper made on a fully patinated artefact, similar to Readymade objects, exhibits interplay between presentation (the appearance and use of the artefact) and representation (its role as a signifier in its new life-phase). This middle ground is, in my opinion, where these items project their significance and play their role in the behaviour and practice of the people involved in their making. It is also where these objects intersect with cosmological and ontological perceptions. This interplay is also displayed visually on the finished product: the patinated flaked item collected for the shaping of a scraper is already of the exact desired size and appearance. Hence, as a finished product, post-recycling, the PPF scraper preserves the majority of the patinated modified surfaces of the old artefact. The new end-product thus presents a newly modified item with its new function while still representing the old item (Fig. 1).

However, size and morphological appearance were not the only criteria according to which patinated artefacts were collected and recycled in that manner. I propose that additional characteristics were involved in the process of their collection, recycling and further use. These are related to the biography of the collected items, and even more so to their itineraries (Hahn & Weiss Reference Hahn, Weiss, Hahn and Weiss2013; Kopytoff Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1988), also visually preserved and thus exhibiting a similar interplay between presentation and representation.

Itineraries of objects: biographies of things and travelling objects

The itineraries of an object refer to its biography as well as its movement in time and space; that is, an object not only has a biography, but also moves within a network. The network has nodes constituted as crossings between things and people. As biography is a linear concept, the term itineraries allow for the expression and exploration of this network of lines. The term expresses the mutual transformations caused by the interaction between people and things (Hahn & Weiss Reference Hahn, Weiss, Hahn and Weiss2013).

An object shifts along life-phases and this movement evokes someone's curiosity along the way (Bradley Reference Bradley2002; Hahn & Weiss Reference Hahn, Weiss, Hahn and Weiss2013). Objects such as the ‘old’ patinated artefacts discussed here are mobile too. The past connotations of the patinated artefacts were chosen to be preserved during their next life-phase as scrapers. In that way, they are always embedded in a multitude of contexts. By keeping the patinated surfaces almost completely intact after the process of recycling, their previous roles, uses and meanings are kept as a memory while new roles, uses and meanings are added.

In addition to use value, some moments of an object's life also have a mnemonic value attached to the object. That is, it has associations inherited in the collected object for the collector/user that assist in remembering something familiar (Harries Reference Harries2017; Malafouris Reference Malafouris, DeMarrais, Gosden and Renfrew2004; Sutton Reference Sutton, Knappett and Malafouris2008). I argue that the collected ‘older’ patinated artefact can be viewed in this manner. The old patinated artefacts were intentionally preserved in the process of recycling them into scrapers—because their surfaces visually present their itineraries. In turn, the ‘old’ surfaces, visually present, represent mnemonic values that create mnemonic experiences for their new users. Thus, while recycled scrapers made on fully patinated artefacts are produced as functional tools, they also function as mnemonic memory objects: they remind their owners about specific events and/or places in the item's lives, or in the owner's life.

I believe it is probable that, while collecting these items, people recognized, from the patinated surfaces, that they had been modified before. Furthermore, in the process of recycling, the knapper might intentionally have chosen to preserve the previous modified surfaces of the patinated artefact out of appreciation for the work of someone else—a human ancestor, as well as out of a sense of familiarity with the process of knapping. As a new tool with a new function, the itineraries of the fully patinated artefact are still preserved on the end-item after recycling (for similar ethnographic and archaeological examples, see Crowell Reference Crowell, Fitzhugh, Hollowell and Crowell2009, 222; Whyte Reference Whyte2014). As such, it takes part in the interplay between presentation and representation.

However, in addition to considering their meaning as the past creations of a human ancestor, I believe we should consider the possibility that these blanks were collected from sites and locations that were meaningful to the collectors (e.g. Reimer Reference Reimer2018). This charges them with a certain value that has to do not only with the scars made by previous knappers and the representation of the past life of a group of people; they are also charged with the value of the chosen location that affords the object its characteristic patina-colour, qualities and circumstances (Reimer Reference Reimer2018 refers to the same idea, calling it ‘pieces of places’). This can be due to ontological properties that were chosen to be presented on the recycled scraper, possibly in memory of a specific site/environment from which it was collected. Certain chosen colours might even have been significant to the collector's/knapper's life and social status (Arthur Reference Arthur2018, 102–3; Berleant Reference Berleant2007; Taçon Reference Taçon1991). In the almost complete preservation of the scars and colours of the older patinated item, the recycled items represent older items and their itineraries as well as people's various mnemonic values and experiences.

Mediators of function and cosmology/ontology

The finished recycled scraper is an object that can instantly be confirmed to belong to more than one context—an old one which involved people and their natural environment, and a new one which involved a different group of people and new tasks. I believe that preserving the previous contexts of the old patinated flaked artefact onwards, into the new finished scraper, was inherent to the process and meaningful to the object's creator. It allowed the object, like Readymade objects, to become a mediator of its different contexts as well as an agent mediating between different objects and persons (in the past and in the present), and between them and their natural environment.

To conclude, memory is inherent to the Readymade process. In my opinion, and as presented here, one cannot make (and see) the ‘memory’ preserved in the patinated scrapers of Qesem Cave without the processes they were going through—those of Readymade conceptual thinking and technique. Hence, in order to preserve the memory in the final recycled object, and come out with a mnemonic item, one has to follow Readymade concepts and technique.

Readymade stands for the difference between passing memory and preserved memory. Readymade processes are acts of memory preservation. The memory occurs with or without the act of Readymade; however, Readymade allows for its preservation and continued presence in a contextualized archaeological record. Art theory, in this case, provides a framework through which it is possible to view specific human actions reflected in mnemonic objects.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the grant UT41/4-1 ‘Cultural and biological transformations in the Late Middle Pleistocene (420–200 ka ago) at Qesem Cave, Israel: in search for a post-Homo erectus lineage in the Levantine corridor’ (A. Gopher, R. Barkai, Th. Uthmeier) of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

The subject was first presented in the ‘NeanderART 2018’ international conference held at the University of Turin, Italy. I would like to thank the organizers of the conference and session where this research was presented. I would also like to thank Sasha Flit and Pavel Shrago for the photographs in this paper.