Introduction

The archaeological study of religion and various activities that show degrees of religiosity (hereafter ‘the religious’) used to be perceived as a narrowly defined specialist field (cf. Insoll Reference Insoll2011, 1). More recently, the religious has become a firmly established theme in general archaeological enquiry (cf. e.g. Hodder Reference Hodder2010; Insoll Reference Insoll2004; Reference Insoll2011; Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2007; Whitley & Hays-Gilpin Reference Whitley and Hays-Gilpin2008). However, this appears to lead to an ironic, unintended consequence: the concept of religion is deconstructed as a clearly definable category of archaeologically recognizable practices/phenomena. Many recent high-resolution contextual studies have revealed the tremendous diversity of religious phenomena (cf. Insoll Reference Insoll2004) and scholars have noted the virtual impossibility of defining religion and the religious by emically recognizing past beliefs with references to the spiritual, supernatural and transcendental—the commonly accepted constitutive entities/elements of religion/the religious (e.g. Keane Reference Keane2010).

Consequently, the following research trends have emerged: (X) a focus on the recognizability of the spiritual, supernatural and/or transcendental and, when their reference/involvement are confirmed, concentrating on a detailed, context-specific investigation regarding how they were referred to, the way in which certain activities were conducted by referring to them, and what effects those activities yielded (cf. e.g. Insoll Reference Insoll2011, Part I); and (Y) giving up the attempt to recognize references to/involvement of the spiritual, supernatural and/or transcendental altogether and, instead, focusing on some formal/stylistic characteristics of religious activities, such as the recursive enactment of certain actions and/or utterances, as analytical units that can be characterized as the religious (e.g. Thomas Reference Thomas and Insoll2012).

These are natural developments resulting in the rapid accumulation of high-quality case studies. However, it must be noted that the Y-type research unwittingly diminishes the significance of the archaeological study of religion/the religious as a unique research field. In Y-type research, religious activities tend to be treated as forming just one of the general social domains or sub-systems where the social (i.e. social order, social system of meaning/value, power, etc.) is reproduced. Meanwhile, importantly, a growing emphasis on the context-specific elements of religions/the religious in both X- and Y-type research leads to the inadvertent avoidance of their diachronic-historical investigation. Therefore, examination centres solely on their synchronic-contextual elements/components. The monumental compendium The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual & Religion (Insoll Reference Insoll2011), for instance, assembles works concerning specific elements and constitutive characteristics of ritual and religion and case studies investigating specific ritualistic-religious categories and/or their unique spatio-temporal settings, all extremely data-rich and of high quality. However, it is noticeable that no specific section nor significant portions are dedicated to long-term historical/comparative themes. The regional case studies featured in the volume also focus on the theme-based, thick description of how specific elements of ritual and/or religion can be approached and understood. So the long-term trajectory of change in ritualistic/religious practices has rarely been investigated (Insoll Reference Insoll2011). This trend is being further accelerated by the fast-spreading influence of flat ontology- and relational ontology-based approaches across the current archaeological theoretical landscape (e.g. Alberti et al. Reference Alberti, Jones and Pollard2013; Crellin Reference Crellin2020; Hamilakis & Jones Reference Hamilakis and Jones2017). I return to this point later.

As the synchronic-contextual-relational increasingly becomes the subject of theoretical and methodological archaeological endeavour in general and in the study of religion/the religious in particular, I feel that the diachronic-historical elements of religious phenomena and how one can make sense of their long-term transformation deserve more attention and more theoretical-methodological investment. Here, I understand the diachronic-historical transformation as the sequence of punctuated drastic changes in the way religious practices were conducted and in the assemblage of mental and material phenomenal units involved in/mobilized for their conduct. This is crucial because, first, although this is a truism, one of the constitutive characteristics and strengths of archaeology is its ability to study the long-term historical transformation of human beings and their modes of existence. Second, it is worth noting that religion has been investigated by pioneers of social sciences, such as Emil Durkheim and Max Weber, as one of the most fundamental social phenomena (Durkheim Reference Durkheim2008; Weber Reference Weber1963). In their work, they try to reveal the mechanism as to how order—which constitutes the social—emerges and is maintained and changed by religious thoughts, imaginations and activities through time. They believe that the study of religion enabled them to reveal the fundamentals, both synchronic and diachronic, of the social. In all, it is more than reasonable to suggest that we need to investigate both the synchronic-contextual-relational and the diachronic-historical-causal elements of religion/the religious if we intend to contribute to the understanding of human beings as social beings through archaeologically studying religion/the religious.

To re-introduce diachronic-historical perspectives to the archaeological study of religion/the religious:

1. I shift the emphasis in defining/recognizing religion/the religious from what makes ‘religion’ religion to how practices that show degrees of (not strictly definable) religiosity function (i.e. how they contribute to the reproduction of society/sociality).

2. I grasp religion/the religious not by what they refer to (e.g. the spiritual, the supernatural and the transcendental) in their operation, but by certain social functions they fulfil. Later, I argue that coping with/overcoming the uncertainties and unpredictability of the world in which people live are the functions that religion/the religious fulfil and, accordingly, this paper defines religion/the religious as unique communicative domains through which the indeterminacy of and risks generated by the world are processed and reacted to, often, but not always, by referring to the unfamiliar and the otherworldly.

At this point, it is beneficial to turn to the works of the sociologist Niklas Luhmann (Reference Luhmann, Bednarz and Baecker1995; 2012; 2013a,b). Luhmann's ‘functional-structural’ approach to the generation and reproduction of sociality and its transformations—a brief summary of which can be found in Mizoguchi (Reference Mizoguchi2020, 5−7)—suits my purpose. It provides a highly inclusive and flexible model, enabling the examination of how a certain range of thoughts and deeds and their media are assembled/networked in an emergent manner to form a self-reproducing domain (such as religion/the religious). Through this approach, I also investigate how this domain affects/is affected by the way other factors/entities exist and operate outside it—some of them also form self-reproducing domains. According to Luhmann, religious activities are differentiated from other types of human communicative activities, such as political and economic activities, by their reference to a distinction between the familiar and unfamiliar and between this world and the other world in their conduct (Luhmann Reference Luhmann, Brenner and Hermann2013a, 183). This definitional recognition/categorization derives from Luhmann's general understanding of society as differentiated into several communicative domains/communication systems including the religious. Such a domain, according to Luhmann, reproduces itself in a self-referential manner and selectively responds to what is happening outside itself by constituting, reproducing and utilizing its own boundary. Such a boundary marks the inside and the outside and the beginning and the end of the domain/system (Luhmann Reference Luhmann, Bednarz and Baecker1995, chs 4 & 5). The presence of a certain item, the utterance of a certain word/phrase, an execution of a certain bodily action, and so on, can mark, delineate and embody such a boundary, (re-)activating a certain set of expectations for a certain type of communicative action by evoking certain feelings, images and memories associated with the expectations. Such expectations include what the appropriate subject matters for the communicative acts are and what consequence(s)/effect(s) the acts would lead to/generate (Luhmann Reference Luhmann, Bednarz and Baecker1995, chs 4 & 5).

Returning to Luhmann's definition, the distinction between familiar and unfamiliar and this world and the other world is drawn upon in one's expectations of others regarding the appropriate subject matter for religious communicative acts and in one's expectations of their consequences and effects. What is of particular importance for the following argument concerning the archaeological recognizability/definability of religion/the religious is that, despite the necessity of referring to the distinction between familiar and unfamiliar and between this world and the other world in choosing the appropriate thoughts and deeds for the religious communicative domain, the above-mentioned boundary itself can be marked by virtually anything as long as a marker can indicate the division between the inside and the outside of the domain. That marking takes place in the form of helping/compelling those who are in the domain to feel, think and act in ways that are meaningful and appropriate for the continued existence/reproduction of the domain. That means anything can be a component of the boundary (material, mental, living, non-living, animate, inanimate, utilitarian, symbolic, mundane and heavenly), differentiating the inside and the outside of the religious domain of communicative acts if it evokes a distinction between familiar and unfamiliar and this world and the other world. In short, anything, themselves not necessarily of unfamiliar/the-other-worldly/supernatural/transcendental nature, can mark certain practices as religious. This highlights the unique difficulty of archaeologically differentiating/distinguishing the religious communicative domain from the other communicative domains: (A) because we can only archaeologically investigate material components of the boundary of the religious communicative domain as the traces of that domain; and (B) because anything, including that which does not have anything overtly to do with the unfamiliar and the otherworldly, can be a component of such boundary.

Here, we should remind ourselves that, as mentioned in the beginning, it is virtually impossible to recognize emically what was supernatural/transcendental in the past and what was not (Keane Reference Keane2010). It is equally difficult to ascertain whether the supernatural/transcendental and the ordinary/natural/immanent were differentiated at all (Keane Reference Keane2010). Besides, as Luhmann argues, the religious communicative domain reproduces itself in a self-referential manner as the other domains do (Luhmann Reference Luhmann, Brenner and Hermann2013a), meaning it generates and transforms the operational mode of its self-reproduction and its differentiation from the other domains through its own operation. So that which is ‘religious’ is in a state of constant change/transformation and always implies indeterminacy.

The above observations and findings compel us to accept that we cannot recognize the presence and operation of the religious communicative domain per se by its archaeologically recognizable material expressions. Rather, we can only study archaeological phenomena that appear to show degrees of religiosity. For this, we must come up with ways to recognize religiosity without referring to the distinction between the familiar/mundane and the unfamiliar/supernatural/transcendental.

Now, I critique the resonance of the synchronic-contextual approach to the religious (the trend to be problematized in this paper) with the rapidly rising and spreading influence of ‘flat ontologies’ across the landscape of contemporary archaeological interpretive endeavours (e.g. Alberti et al. Reference Alberti, Jones and Pollard2013; Hamilakis & Jones Reference Hamilakis and Jones2017). I critique flat ontologies-based approaches to help formulate an alternative archaeological approach to religion/the religious. A flat ontology (e.g. Harman Reference Harman2002; Reference Harman2011) recognizes the whole range, or assemblage, of material entities/differences, including the living, non-living, animate, inanimate, units of feelings, units of thought/perception, and so on, to have each its own mode of existence and the potential of affecting the way in which other such entities/differences exist. This understanding of the world and of being deconstructs unitary/singular causation, teleology, dualistic/Cartesian world views, and the privileged status given to human beings and to any specific human category (often White men) over other beings and other human categories (e.g. Alberti & Marshall Reference Alberti and Marshall2009). This philosophical stance promotes the focus on the constant and contingent occurrences of change of any scale and nature to any number of such entities/differences that may/may not lead to changes/networked-relational responses in understanding continuity and change (cf. e.g. Crellin Reference Crellin2020). In this view, categorizing social phenomena into distinct domains and trying to find causal connections between them (and between them and non-social factors) is not so important. This is because social realities are constituted by meshed relations among everything that emerges, is sustained, territorialized, de-territorialized and transformed in different manners at different sites (whose boundaries are also open and changing) of different scales and characters (i.e. individuals, groups, places, etc.). Advocates of flat ontologies observe and describe what is meshed, in which manner, at what scale, and how this meshing affects that which is meshed, leading to change.

I wholeheartedly accept the power of flat ontologies-based approaches in the nuanced, interpretive description of correlated phenomenal units that can be recognized and investigated archaeologically, and fully recognize its potential to sensitize and empower us radically to relate our archaeological understandings of the past to our daily experiences of contemporary social realities (e.g. Crellin Reference Crellin2020, 221−4). I am also aware of its significant implications for the understanding and possible incorporation of ‘animistic’ ontologies to the study of the religious (cf. Porr & Bell Reference Porr and Bell2012). I return to this point later. Nevertheless, it seems that advocating flat ontologies excessively favours the synchronic-contextual over the diachronic-historical by strategically ignoring causal elements in the networking/assembling of things, prioritizing their flat, mutual relationality. Although I am fully aware that advocates of flat ontologies recognize the causal agency/power of the emergent effect of the meshing/assembling of a certain set of mental and material phenomenal units of various scales (e.g. De Landa Reference De Landa2006), I believe that the excessive emphasis on fluidity in the meshing of things/phenomena prevents us from examining how and why the mode of the meshing/assembling changes.

Additionally, I suggest that flat ontology-based approaches are powerful in making sense of continuous changes in the way practices were conducted and in the assemblage of mental and material phenomenal units involved in/mobilized for their conduct in a cumulative manner, but are not powerful in making sense of the long-term sequence of punctuated drastic changes in the way practices were conducted and in the assemblage of mental and material phenomenal units involved in/mobilized for their conduct. As described later, there are often recognizable points in human history when both the mode of the meshing of mental and material phenomenal units and what were meshed (i.e. mental and material phenomenal units that were distributed, connected, separated and inter-penetrated) were drastically changed.

To overcome this unintentionally generated tendency, I look again to Niklas Luhmann's framework. Luhmann's grasping of religious acts as generating a religious communicative domain that, together with other types of such domains, constitute society as a whole derives from the ontological position that communication constitutes the smallest and the most basic unit of social phenomena (Luhmann Reference Luhmann, Bednarz and Baecker1995, ch. 4; Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2020). The modes/patterns of ever-transforming meshes of connections/relations among a whole range of material entities/differences, including the living, non-living, animate, inanimate, units of feelings, units of thought/perception, and so on, that constitute the foundation of sociality, are constituted through individual communicative acts situated in communicative domains. From this point of view, I propose to differentiate and choose the domain of communicative acts as an archaeologically recognizable (see below) and analytically and heuristically privileged phenomenal unit where effects that are generated by the changing networking/meshing/constellation of material entities/differences cause observable effects (i.e. change(s)) to itself and to the other domains constituting society as a whole.

Along with the adoption of communication as the basic analytical unit or the study of change, I argue that regaining the sense of causality and reinstating the categorization of causal units as a significant analytical task are necessary and of crucial importance for re-introducing diachronic-historical perspectives to the study of archaeology in general and the archaeological study of religion/the religious in particular. I propose that the study of religion/the religious cannot be achieved unless we shift our emphasis from what makes ‘religion’ religion to which practices generate (not strictly definable/recognizable) religiosity and how they work or how they contribute to the reproduction and transformation of society/sociality in a religious manner. To put it differently, we need to approach religion/the religious not for the specification of what they are about, but for the understanding of how they emerge and how they work. This proposition redefines religion/the religious by what function it fulfils—for how it works for the constitution/reproduction of society/sociality, not by what they are concerned with (such as undefinable and emically unapproachable entities/concepts such as the supernatural/transcendental). In summary, we need to re-introduce causal explanatory potential to the archaeological investigation of religion/the religious by differentiating it as a communicative domain where a network/assemblage of material differences generates a certain mode/modes/patterns of religious functional effects.

By drawing upon these critical observations on the current state of the archaeological study of religion/the religious and thoughts for its future, I offer the following concrete strategy for constructing a novel procedural framework for the archaeological study of the long-term change of religion/the religious.

1. Re-defining the religious

‘Religious activities constitute a distinct communicative domain that functions by responding to and processing the uncertainties and risks that the world (as the synthesis/unity of the social and the natural as a phenomenon) generates’. The word ‘function’ here is meant to reproduce itself and continues affecting the state of the other domains constituting society as a whole in a self-referential manner. The word ‘respond’ here is meant to enable people to cope with uncertainties and risks they may encounter in their lives by portraying them as the effect of the unfamiliar/the otherworldly (including the supernatural and the transcendental). ‘Process’ is meant to enable people to choose how to make sense of and come to terms with the realized risks (i.e. disappointments/bereavements/devastations, etc.) by portraying them as the effects of the unfamiliar/the otherworldly (including the supernatural and the transcendental). Both the responding and processing take place by perceiving and portraying certain uncertainties and risks generated by the world as inevitable and by, often, but not necessarily always, attributing their causes to the unfamiliar/the otherworldly (including the supernatural/transcendental). As repeatedly mentioned, however, it is highly difficult in the first place to ascertain references to/beliefs in the other worldly/supernatural/transcendental for archaeological evidence emically. Therefore, references to/beliefs in the otherworldly/supernatural/transcendental are bracketed out and are considered only when possible and necessary.

2. Specifying the subject and the scope of the study according to the re-definition

Adopting this heuristic re-definition means those archaeological phenomena that can be investigated as responses to/processing of the uncertainties and risks generated by the contemporary world are all recognized as religious phenomena. Thus we can avoid becoming entangled in the impossibility of specifying the subject and scope of our investigation. This definition also strategically derives from the tradition of sociological-functionalist approaches to religion (cf. Luhmann Reference Luhmann and Barrett2013a; Parsons Reference Parsons1951) for the purpose of making sense of the long-term change of the religious by correlating archaeological religious phenomena to the variables (i.e. the significant sources of risks and uncertainties of respective archaeological phases/temporal phases of archaeological investigation) that can also be approached archaeologically.

3. Setting up an operational theoretical model

As a precondition for such responding and processing to take place, a certain range of communicative acts, which constitute the mode of responding and processing, needs to be reproduced. What is important here is the fact that noone can prove that the unfamiliar/the otherworldly/supernatural/transcendental that are referred to in religious communicative acts really exist, and that is the case in the past as well as in the present. This makes inevitable the very fact that such interaction/communication continues is the only foundation upon which responding and processing can be judged as meaningful.

Such communication (i.e. religious communication) needs to take place when necessary, often after various lengths of time-space gaps. For this to be made possible, its mode needs to be internalized by its (potential) participants. Furthermore, religious communication is a certain set of mutual expectations about who should behave in what manner in a particular domain of communicative acts that need to be generated and shared by people who are potentially involved in the reproduction of that domain. For such a set of mutual expectations to be reactivated when necessary, various tangible, intangible, material and non-material devices need to be in place, internalized and embodied by those who are potentially involved in the communication, thus spatially and temporally marking the domain of the interaction/communication and differentiating it from the other domains.

Using the above strategy, this paper formulates and proposes an application procedure for the study of the long-term change of religious practices. The procedure comprises the investigation of the following: (A) what uncertainties and risks of the world were generated and differentiated in a certain social formation; (B) how they were responded to and processed in terms of the content of the communication and the character of its material media; and (C) how the mode of responding and processing changed as society changed. In short, the correlation/co-transformation of the religious communicative domain with changing uncertainties and risks that the world generates is investigated. The applicability of the framework will be illustrated with relevant pre- and proto-historic Japanese archaeological evidence.

Proposing the procedure

To analyse the long-term transformation of the religious communicative domain by examining its correlation/co-transformation with changing uncertainties and risks generated by the world, first, I must formulate a general model outlining how the domain is reproduced. As already mentioned, I do this by drawing upon the framework of the sociologist Niklas Luhmann, who grasps communication as the minimum and the most basic of social phenomena and whose continuation generates a ‘system’ that reproduces itself in a self-referential manner (i.e. drawing upon its own past experience) by selectively reacting to the complexity of its environment (comprising other communication systems and other elements, both social and natural) (Luhmann Reference Luhmann, Bednarz and Baecker1995; Reference Luhmann and Barrett2012; Reference Luhmann and Barrett2013b).

For any communicative act (i.e. an utterance, a bodily movement, etc.) to be continuously connected to the next communicative act to form a distinct communicative domain/system, those who are involved in such domains need to share a set of mutual expectations as to (X) how the others would act and (Y) how the others would expect one to act in a certain circumstance (Luhmann Reference Luhmann, Bednarz and Baecker1995; Reference Luhmann and Barrett2012; Reference Luhmann and Barrett2013b). That is because we cannot observe, in real time, what is going on in the minds of the others, rendering it inevitable that we would guess how they would act in a certain circumstance. The existence of such mutual expectations enables those who are involved in such a sequence of communicative acts to choose either to comply or not with the expectation, further enabling them to decide how to react to others’ choices and their concrete expressions. For the mutual expectations to be activated, certain ‘markers’ that evoke and activate such mutual expectations and function as the ‘boundary’ between the inside and the outside of the domain (i.e. indicating what is relevant/irrelevant for the continuation of the sequence of communicative acts) need to be differentiated. Such markers can be certain utterances, body actions and material items/material differences. These material items/material differences include both portable and immobile ones, the latter including buildings, landscapes, natural phenomenal-scapes such as the sky and elements such as temperature, weather, and so on. In the archaeological investigation of the religious communicative domain, two fundamental subject matters are part of our investigation:

• how to recognize these boundary markers; and

• how to reconstruct the mutual constitution and mediation between these boundary markers and certain communicative acts (chosen by drawing upon the mutual expectations evoked/activated by the presence of those markers).

If we define society as a phenomenon that is constituted by communicative acts that generate, differentiate and deal with the uncertainties and risks generated by the world, construct regularities out of their own operations in different manners, and are mutually connected in such a way as to engender emergent properties including sociality, this means that different societies with different ‘complexities’ regarding how certain communicative domains are differentiated, situated in a certain time-space horizon and linked/connected/inter-penetrated:

• would generate different uncertainties and risks to be dealt with and, accordingly,

• the communicative domains that are differentiated, the kinds of mutual expectations that are needed to reproduce those domains and the sets of markers that mediate their reproduction would all be different between different societies with varying complexities.

To summarize, the following can be deduced:

A. Different ‘communicative domains’, with different kinds of mutual expectations and different sets of markers differentiated for their reproduction, would be differentiated between different societies with different complexities.

B. The trace of the reproduction of a certain religious communicative domain can be recognized in the form of its distinct markers and the media of its reproduction.

C. The content(s) of a certain religious communicative domain can be approached through the examination of the way in which such markers/media emerge/are assembled/are networked and through the examination of what they represent/signify/embody/evoke.

D. By correlating those observations with the characteristics/complexity (as defined above) of a certain society and the uncertainties and risks it generates, the concrete content(s) of the religious communicative domain which that society generates can be reconstructed.

Drawing upon these, I can formulate a programme for the archaeological reconstruction of the long-term transformation of religion/the religious, comprising three operational stages.

Stage 1: Reconstructing the type(s) of uncertainties and risks that are responded to and processed by its religious communicative domain by examining the structure/organization/complexity of a given society.

Stage 2: Reconstructing how such uncertainties and risks are responded to and processed in/by the religious communicative domain by examining what the markers/media of its boundary represent/signify/embody/evoke.

Stage 3: Reconstructing how such representation/signification/embodiment/evocation contributes to the responding to and the processing of the uncertainties and risks by examining how such markers emerge/are assembled/are networked.

The Stage 1 investigation can be conducted by reconstructing the uncertainties and risks emerging from the ecological and socio-cultural/historical environment/content of a given society and its dominant subsistence, production and exchange systems that structure the time-space distribution of the differentiated communicative domains.

The Stage 2 investigation can be conducted by examining the system of meaning constituted by the archaeologically recognizable/approachable markers/media.

The Stage 3 investigation can be conducted by examining the things or occurrences that are represented/signified by the markers/media, reflecting the contents of the uncertainties and risks that must be reacted to and processed.

Case study

The following long-term change of the religious communicative domain can be reconstructed to have unfolded in the Japanese archipelago between c. 10,000 bce and ce 700 by applying the above-illustrated framework.

It should be emphasized that I do not intend to provide an exhaustive introduction to the archaeology of this period; relevant episodes and facts will be selected to illustrate applicability and potential of the framework formulated above. The cases chosen are selective, accordingly, and whereas those that are chosen for the study of the period between c. 10,000 and 600 bce are mainly from eastern Japan, those that are chosen for the study of the period from 600 bce onward are from western Japan. There certainly exist regional differences in the tempo and character of change between regions; but they are chosen to represent and exemplify the overall trend of what was happening across the archipelago (admittedly, excepting the Hokkaido and Okinawa islands). It should also be added that each phase of the long-term transformation process, punctuated by drastic transitions, saw gradual changes going on within it (e.g. Barnes Reference Barnes2015; Habu Reference Habu2004; Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013).

It should not be misunderstood that the four-phase long-term transformation process, which is to be illustrated, is a unilinear ‘evolutionary’ process. The uncertainties and risks that characterize each of these phases were generated by an assemblage of factors that themselves did not ‘evolve’ but were formed by historically contingent conditions. It should also be noted that shifts from one phase to the next in the process might coincide with ontological shifts. However, the way in which the shift is explained (i.e. in terms of change in the uncertainties and risks to be responded to and processed and in the way the uncertainties and risks were responded to and processed) does not coincide with the form and content of the ontology of the people of respective phases, nor was such a coincidence intended (cf. Porr & Bell Reference Porr and Bell2012). The issue regarding how we can respect and incorporate emic epistemic-ontological perspectives into the framework, which this paper is proposing will be tackled in a future study.

It should also be emphasized that the religious communicative domain is a self-reproducing domain, and it selectively responds to changes that take place in other communicative domains that generate uncertainties and risks. It would be certainly desirable to describe fully how the other communicative domains operate. However, mainly from shortage of space, this paper focuses solely on the operation of the religious communicative domain.

The Initial Jomon through to the Final Jomon period (‘Phase 1’: c. 10,000–600 bce)

This phase, during which time the procurement of food and other resources was based upon hunting, fishing and foraging, saw the cumulative development/refinement of technology for the efficient utilization of seasonal resources (Noshiro et al. Reference Noshiro, Kudo and Sasaski2016; Sasaki & Noshiro Reference Sasaki and Noshiro2018). Sedentism developed as the post-Pleistocene warming enhanced the carrying capacity of regional ecotones, leading to a slow but steady population increase (Imamura Reference Imamura1996). It also brought about the gradual formation of regional communal groupings that can be recognized archaeologically by differentiating between large settlements, with the traces of various extra-subsistence, communal activities such as burials and various rituals, and smaller settlements surrounding them (Kobayashi Reference Kobayashi2004). The smaller settlements might have been seasonal settlements occupied by segments of larger communal/corporate groupings such as clans, and the larger ones the ‘base’ where those smaller groups gathered to live for certain seasons of the year (we shall come back to the supportive evidence for this inferential modelling later), together forming a regional unit. From the second half of the Early Jomon phase onward, such regional units became fairly equally spaced in some certain regions of eastern Japan such as the southern Kanto, suggesting the formation of communal territories (Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2005). However, such a system appears to have been highly vulnerable to various environmental, demographic and other socio-natural/cultural fluctuations, often resulting in abrupt population decreases and social collapses. The most dramatic of these took place around the Chubu and Kanto regions of central Japan toward the end of the Middle Jomon (Imamura Reference Imamura1996) (although the exact cause(s) of this event, marked by an abrupt decrease in population size, remains unclear: see Crema & Kobayashi 2020).

Uncertainty in the annual availability of seasonal subsistence resources, as reflected in occasional settlement system collapses, would have been the constitutive uncertainty and the major source of risks of the phase. The stabilization of the membership of descent and larger communal groupings, suggested by the establishment of the above-mentioned regional settlement systems, the emergence of pottery style zones and the formation of clear burial agglomerations/clusters in individual cemeteries (often situated at the centre of regional centre-type large settlements) made up of distinct burial areas for a moiety/lineage/lineage segment-type grouping (Fig. 1), would have produced uncertainty in finding marriage partners, in exchanging resources and in regulating intra- and inter-communal relations. Thus, these were significant sources of uncertainty, risk and personal/communal panic of the phase as well. Uncertainties and risks generated through the reproduction of various social relations of the above-mentioned kinds would have been enhanced and exacerbated by climatic fluctuations, suggesting that those domains would have formed a unified background against which the ontology of the people of this phase was constituted.

Figure 1. An example of regional centre-type large settlements: the Nishida, Iwate Prefecture. (After Iwate Prefectural Board of Education 1980; from Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013.)

Seasonally distinct labour organizations, generated through procuring seasonally different assemblages of available resources, would have generated seasonally differentiated modes of social, and hence power, relations between different categories of people. Those seasonally changing modes of labour and social-power relations would have connected different categories of people to seasonally different/seasonally changing assemblages of animals, plants, landscape terrains and features, and so on, rendering the relationships among different categories of people and living and non-living creatures/material differences in contact with them to be fluid, interpenetrating and interchangeable. Through such fluidity, interpenetrability and interchangeability among living and non-living beings and other material differences that inhabited and constituted the world, we can comprehend the bases of an ‘animistic’ ontology (‘animism’ here being defined as follows: ‘[a]n expression of a relational idea of human–environmental relationships’: Bird-David Reference Bird-David1999, cited in Porr & Bell Reference Porr and Bell2012, 162). This would also have constituted what the religious communicative domain of this phase needed to process or ‘tame’.

For responding to and processing risks, the religious communicative domain appears to have been internally differentiated into, while mutually inter-penetrating, several sub-fields—each marked and embodied by different material items/material differences of different natures and scales, as shown below—which processed different uncertainties. Concurrently, the fluidity, interpenetrability and interchangeability between living and non-living beings, and other material differences, caused by seasonally changing modes of labour organization, sets of animals, plants and other resources, seem to have rendered different ‘representations’. The term might be misleading in that those representations themselves might have been perceived to have their own thoughts, wills and vitalities, as far as ‘animistic’ ontologies are concerned (cf. Bird-David Reference Bird-David1999). Here, living and non-living creatures and features and their parts, such as insects, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, landscape features, human sexual organs, and so on, are densely juxtaposed with no clear boundaries between them and often depicted in conjoined states in material items such as pottery, clay figurines and various ‘non-utilitarian’ items (again, the term might be misleading for the same reasons as above) (cf. Higuchi et al. Reference Higuchi, Takafumi and Kobayashi2011) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Katsuzaka type pottery from the Middle Jomon period. (From Higuchi et al. 2011.)

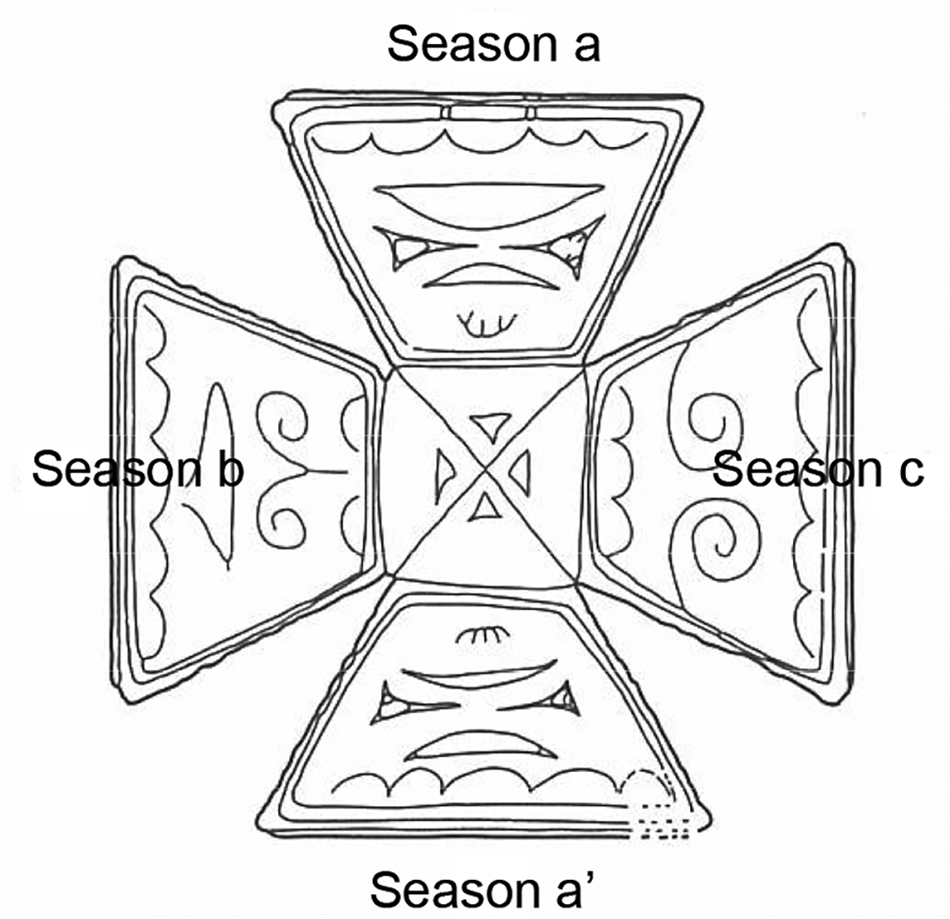

For instance, the unique development of clay (sometimes stone) figurines depicting pregnant women, animals and plants would have embodied (not metaphorically but, regarding animistic epistemologies and ontologies, the figurines might be perceived as actual, tangible, or literal; cf. Porr & Bell Reference Porr and Bell2012) connections between the cyclic regeneration of animal and plant life and that of human life signified/symbolized by the fertility of women. Various ritualistic cares would have been taken for the well-being of women, interchangeable with that of plants and animals. This very interchangeability is well embodied by the pots on which clay figurine-like human depictions are embedded in the assemblage of animal and other depictions, possibly including that of landscape features (cf. Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2020). Some pots appear to have symbolized the cyclic flow of the seasons (Fujita Reference Fujita2007) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. An opened-up-cube representation (seen from above) of a square bowl-shaped vessel from the Asahi site, Niigata Prefecture. Note the wavy line motif with different numbers of waves and different combinations of linear and geometric motifs on the panels. (After Fujita 2007.)

Most items of highly symbolic (or, perhaps more appropriately, ‘animistic’) nature were used and discarded, at times in large amounts, at above-mentioned regional centre-type large settlements (from the Middle Jomon onwards) (cf. Fujimura Reference Fujimura1999). Central and eastern Japanese examples often took a concentric circular form (Fig. 1). Generally, the innermost area was occupied by burials (as mentioned, divided into a number of clusters, likely distinct burial units for communal segments such as moieties/lineages), that were surrounded by storage facilities and further surrounded by pit dwellings (Fig. 1) (e.g. the Nishida site of Iwate prefecture: Iwate Prefectural Board of Education 1980). In addition, these circular spaces were divided into multiple segments that appear to have been related to communal group divisions and can be connected to above-mentioned burial clusters situated at the centre of those settlements (Taniguchi Reference Taniguchi2005). Some of those circular settlements were designed to mark certain directions from the centre. For example, the lines of sight of those who stood at the centre of the settlements were designed to be drawn by standing stones situated at certain positions towards prominent mountain peaks of the environs, which could signify the annual flow of time (Miyao Reference Miyao and Kobayashi1999).

Those constitutive traits of the regional centre-type large settlements of central and eastern Japan suggest that such spaces would have been designed to process (1) the uncertainty relating to seasonal subsistence resource procurement, significantly mediated by the figurines, pots and other symbolic items that were used and discarded there; (2) the uncertainty relating to intra- and inter-group relations, significantly marked by the segmentation of settlement and cemetery spaces and mediated through various practices conducted there; and (3) the uncertainty relating to the reproduction of animal, plant and human life, significantly mediated by the cyclic conception of the flow of time, marked and signified by the spatial structure of the settlements and the parallel spatial division of pottery surface into bounded segments, ‘dwelt in’ by various living and non-living creatures and features.

In all, it was difficult to intervene and change by human acts those types of uncertainties and risks that were made sense of and overcome through various communicative acts mediated by those material items/differences. Here, the relationship between human beings and natural beings tended to be materialized as symmetrical, interpenetrating and mutually transformative. In that sense, the religious communicative domain reproduced itself not by referring to the otherworldly, but referring to the untamed this-worldly.

The Yayoi period (‘Phase 2’: c. 600 bce–ce 200)

This phase witnessed the rapid increase of social complexity and the scale of social integration. Although not solely, it was significantly ignited by the beginning of rice paddy-field agriculture and accelerated by the expansion of interaction and exchange networks (for background information, see Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013). The introduction, from the southern coastal region of the Korean peninsula, of systematic paddy-field rice farming (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013) would have led to the ‘hierarchization’ of uncertainties and risks (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2020). This meant that the uncertainties and risks generated by rice farming, as the dominant field of labour/production activity (concerning the spatio-temporal horizon scale it occupied and because rice was a major food source: cf. Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2019), made rice-farming-related uncertainties and risks a priority over other types of uncertainties and risks (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2020).

There were several significant changes to material items that marked the religious communicative domain and mediated the reaction to and processing of the uncertainties and risks that characterized the phase. One of the most important is that the juxtaposition and interpenetration of living and non-living beings disappeared almost completely in Phase 2. Where conjoined/mutually inter-penetrating states on certain material culture items, most typically on pottery (see Fig. 2), had characterized Phase 1, depictions that are clearly distinct and identifiable characterized Phase 2. Certain insects, animals and human categories (that are commonly dualistically identifiable as either female and male), tools (such as pestle and mortar) and architectural structures (such as raised-floor buildings) are depicted either individually or in groups (Fig. 4a) (see e.g. Society of Yamato Yayoi Culture 2003) or, in rarer cases, forming a sequential order (Fig. 4b) (see e.g. Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, 171−80). They do not appear to be (the embodiment of) animistically animated and interpenetrating/interchangeable beings. They appear to signify certain living beings that occupy certain spatio-temporal positions in a mythological narrative sequence or system that explain the origin and order of the world (and the uncertainties and risks it implied) (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, 171−80). When depicted singly, a given living being or an item would have evoked/activated the knowledge of the whole or a certain part of such a narrative sequence/system, dictating to those with access to the item how s/he should think and act to fulfil the role allocated to her/him in the mythological order.

Figure 4. A piece of Yayoi pottery from the late phase of the Middle Yayoi period (a), and a Dotaku bronze bell with depictions of various creatures, human figures, and a raised-floor building (b). (a) From the Karako-Kagi site, Nara Prefecture. Note two human figures holding an implement (probably a halberd) and a shield, four fish, a deer with an arrow stuck on its back, and a raised-floor building. (From Society of Yamato Yayoi Culture 2003.) (b) Said to be from Kagawa Prefecture (height: 42.7 cm). Note the flow of scenes from the top to the bottom (a–f) tracing the pseudo-evolutionary/hierarchical sequence from insects through amphibians, birds and mammals to humans (and a raised-floor building). See Mizoguchi (Reference Mizoguchi2013, 171−80) for detailed analysis and interpretation. (From Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013.)

When depicted as forming a sequence or a system, like a small number of the Dotaku bronze bells (Fig. 4b; Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, 171–80), the portrayed creatures, human individuals and tools would not have been perceived as having their own lives and vitalities that could directly affect the lives of those who accessed them (compared to the creatures depicted in the Jomon era, where they would have been believed to have inherent vitality and agentive powers themselves). Instead, they represent a mythological narrative that explains the genesis and the order of the world to instruct those with accesses to them how to live their lives, structuring their beliefs and effectively telling them how to respond to and process the uncertainties and risks of their world. Concerning the sequence depicted on the Dotaku bronze bells, different creatures and features appear to have been situated in an evolutionary/hierarchical system/order. The depiction of insects was followed by that of amphibians, then animals, then further followed by human beings, and ended in the depiction of an architectural structure (a raised-floor building) (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, 171–80). Various inferential-interpretive models have been put forward, but the following can be said for sure:

• The genesis and the order of the world was depicted to be evolutionary-hierarchical in which human beings were situated at the highest position.

• The vitalities and agentive powers of the creatures, that characterized the depicted relationship among humans, other living beings, and non-living beings in Phase 1, became abstracted (and tamed) in the form of their respective roles/functions situated in the evolutionary-hierarchical narrative system.

• The above would have marked the end of the animistic-shamanistic mode, so to speak, of the reproduction of the religious communicative domain.

In this phase, the degree to which human intervention could reduce, or react to, uncertainties and risks increased, and the relationship between humans and natural beings shifted from a mutual transformative one to the one where the former was intervening in the state of the latter. For instance, this phase witnessed, for the first time, the depiction of human beings modifying the state of natural beings (e.g. in hunting scenes). (There exist a small number of Late Jomon pots depicting ‘hunting scenes’; but they, interestingly, only depict bow and arrow and an animal commonly inferred as a bear. The non-depiction of human individuals in the scenes suggests a different ontological relationship between human beings and natural beings from what is depicted in this phase: Fukuda Reference Fukuda2019.) The hierarchization of uncertainties and risks progressed in tandem with the hierarchization of social relations and led to the formalization and esotericization of certain religious knowledge. This knowledge was increasingly exclusively possessed by the elite, resulting in a shift from the animistic-shamanistic mode to the priesthood mode of the reproduction of the religious communicative domain. Depictions of priest-like figures on the pots which, considering the contexts where they were excavated, would have been used at religious-ritualistic scenes vividly illustrate this.

In some such examples, priest-like figures hold a halberd and a shield, suggesting that the rituals included mock battles (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2020, 19–20; Fig. 4a). This inference is supported by the presence of various types of weapon-shaped items, including halberds and shields, made of wood (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2020, 19–20; see Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, 131−4, especially 133, fig. 6.10). Ethnographic examples from Asian rice-farming areas show that such mock battles were conducted against evil spirits disrupting the growth of rice or to encourage the growth of rice by threatening its own spirit (Iwata Reference Iwata1970). In any case, these inscribed figures are likely to depict actual scenes of ritual activities. This marks a fundamental departure from Phase 1. Those inscriptions were made on a smoothed surface to signify and represent the acts conducted by a certain individual(s) and the tools, animals and material items that were used/involved in the acts. In contrast, in the case of Jomon pottery, as interpreted above, such a surface would have been created and perceived as a microcosm itself, in which creatures inhabiting the life-world and features comprising the physical structure of the life-world were recreated to ‘live’ there. In stark contrast, the Yayoi pottery surface functions as a blank canvas on which representations/signifiers of something else, including not only entities such as creatures and features but also actions such as ritual conduct, were depicted (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2020, 20).

It is vital to note that the pots on which scenes of ritual conduct/actions were inscribed would have been brought to and used at such scenes as those the depictions themselves illustrated. This suggests that the inscriptions and the depicted scenes instructed those who were present at such scenes with the pot with its inscribed entities how to act. Now, the religious communicative domain was functioning to instruct people about how to react to and process the uncertainties and risks of the world (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2020, 20).

As the instructional function of the religious communicative domain increased, guiding people about how they could process rice paddy-field farming-generated uncertainties and risks by revealing how the world came to be and how it works, it appears to have become progressively more esoteric. The Dotaku bronze bells, a material item exemplifying and epitomizing the way the religious communicative domain of this phase functioned, suddenly disappeared, and, as if replacing them, keyhole-shaped burial mounds emerged as the most significant boundary marker of the transformed religious communicative domain, marking the beginning of the next phase (cf. Iwanaga Reference Iwanaga1997), the Kofun (‘ancient tumuli’) period (cf. e.g. Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, chs 9 & 10). If these ritual items had been used both in elite and common religious communicative scenes, their use would have continued into the Kofun period as ordinary ritual materials. Their abrupt disappearance from the archaeological evidence strongly suggests that they came to be used exclusively by the elite in the elite religious communicative domain (which would have become an exclusive field marked by/formalized with increasingly esoteric knowledge; see below). Here, they were so detached from the world of the commoners that once the elite changed their way of conducting religious communications (i.e. by constructing keyhole-shaped tumuli and burying the dead in them), the Dotaku and other items used exclusively in the elite religious communicative domain no longer instructed commoners about how to react to and process the uncertainties and risks of the world, and were destined to disappear (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, chs 9 & 10).

The Final Yayoi through the Earlier Kofun period (‘Phase 3’: c. ce 200–500)

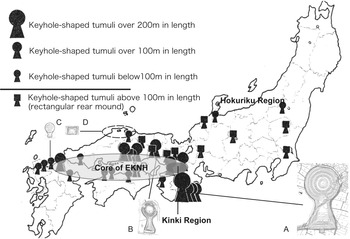

The period leading to the emergence of the earliest keyhole tumuli, definitionally marking the beginning of the Kofun period in Japanese pre-history (cf. Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013), witnessed the formation of an extremely wide interaction network horizon covering almost the entirety of western Japan and the western part of eastern Japan, across which the earliest keyhole tumuli were constructed (the ‘Early Kofun Network Horizon’, hereafter EKNH; Fig. 5) (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2009; fig. 10). This was ignited by the following parallel, mutually enhancing processes that were set in motion during Phase 2 (see above): (a) the increasing density and frequency of inter-communal contacts and the growing reliance on them by communities, and particularly their elite (residing at the regional central place-type settlements), for their reproduction; (b) the intensification of inter-communal competition over dominance in such contacts, and over the exchange of goods (including iron material of iron tool production; steel-making technology was not introduced nor adopted/established in the archipelago before the fifth century ce/the middle Kofun period), information and people; and (c) the rise of the Chinese empire as the ultimate source of authority and the legitimation of dominance (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2009; Reference Mizoguchi2013, 220−40). These factors, together with the rapid and vast expansion of the horizon/network of inter-communal interaction, would have made the elite communicative domain a crucial one out of the internally hierarchically differentiated religious communicative domain for the reproduction of society, and rendered the uncertainties and risks generated by its sustenance a vital set of uncertainties and risks to be reacted to and processed. This requirement appears to have been fulfilled with the metaphorical embodiment of the dead chief as the supreme priestly figure of the order of the world. This newly emerged mode of the reproduction of the religious communicative domain overcame regional differences and barriers in the way the uncertainties and risks were reacted to and processed compared to the previous phase.

Figure 5. Network horizon represented by early keyhole tumuli. Note the size differences. Some examples of different-shaped tumuli: (A) Hashihaka; (B) Yoro-Hisagozuka; (C) Taniguchi; (D) Onari. (After Hirose Reference Hirose2003; from Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013.)

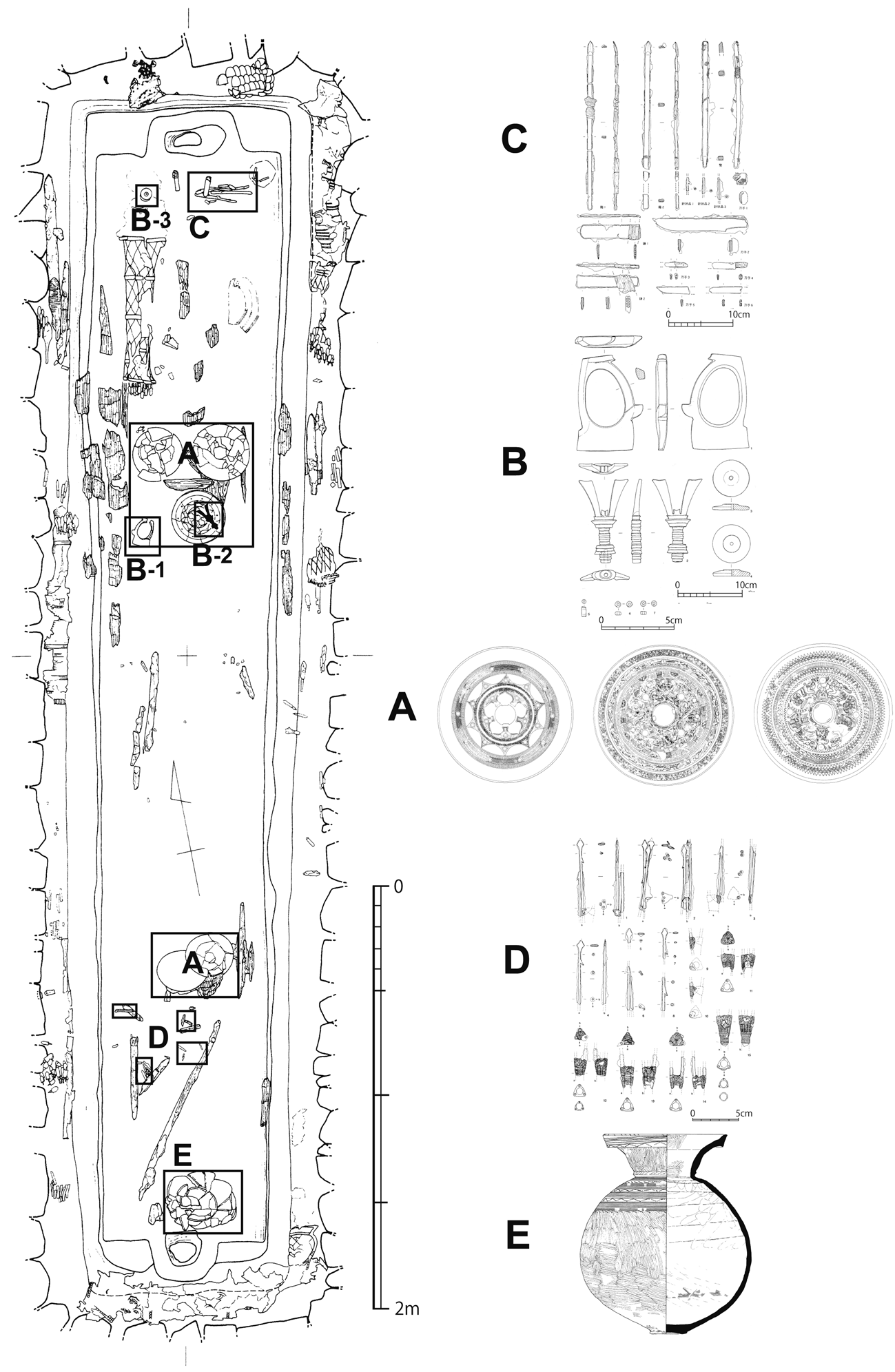

The typical grave goods assemblage of the Early Kofun period (Fig. 6), homogeneously shared wide across the EKNH (Fig. 5), comprised distinct function-specific sets of items such as those for woodworking, farming, fishing, fighting/warring and ritual that were differentially placed on the bottom of the cist, surrounding the body (Fig. 6) (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, 249−54). The iron tools comprising those sets often consisted of (A) weapons, (B) woodworking implements, (C) agricultural implements and, albeit rarely, (D) sea fishing implements. ‘D’ is an interesting component, significant for the consideration of the nature of the assemblage regarding the fact that fishing implements are commonly found in tumuli situated far away from the sea (Fig. 6D). These appear to represent the significant spheres of social life, in terms of all the important types of labour and, hence, the major sources of uncertainties and risks (i.e. (A) weapons = communal defence, (B) woodworking implements = wood handicraft, including those used for agricultural work, (C) agricultural implements = agricultural activities, and (D) sea fishing implements = sea fishing activities (cf. Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, 236−7). The iron tools, in this sense, metaphorically represent significant interfaces with different sources of uncertainties and risks, generated by both the natural and socio-cultural environments experienced by people. In addition, the tools classified under (B), (C), and (D) might also have represented the three environmental-natural components of the entire life-world, with (B) representing the mountain, (C) representing the floodplain and (D) representing the sea.

Figure 6. The placement of different categories of artefacts with distinct symbolic meanings: the Yukinoyama tumulus, Shiga Prefecture. (A) Bronze mirrors; (B) stone implements; (C) iron woodworking tools; (D) iron fishing implements; (E) pottery globular jar. (After Fukunaga & Sugii Reference Fukunaga and Sugii1996, with additions; from Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013.)

The assemblage also often included mirrors called ‘Sankaku (triangular) - en (rimmed) - shinju (with the deity-beast motif) - kyo (mirror)’ (Fig. 6A). At present, scholars are involved in a fierce debate as to whether the typologically earlier categories of the specimens were made somewhere in the domain of the Chinese Wei dynasty or where they were distributed (i.e. the present-day southern Kinki region; e.g. Fukunaga et al. 2003). Regardless of where they were made, however, one can safely say that they represented an alien system of meaning and contacts with authority and power residing outside the domain within which the communities (and their elite) could potentially communicate. Again, the dead chief buried with them signified a competency in contacting the other/the outside of the life-world and, therefore, effectively, was symbolically rendered to embody and represent this world.

Overall, many of the attributes of the earliest keyhole tumuli metaphorically represented the world—the integration, work and history of which were symbolized by the tumulus and by the dead chief who was buried in there. The attributes also represented the three main environmental-natural components of the lived-world (i.e. the mountain, the floodplain and the sea) and the distinct activities conducted in them. Moreover, the keyhole tumulus was utterly new in terms of its gigantic scale, as well as its shape—beyond comparison with its regional predecessors. Hence, it was alien even to those who constructed it and buried their elite dead for the first time. In short, the earliest keyhole tumulus represented the beginning of the history of the integration, and that of the working of the world across which the tumulus and the mortuary custom embodied by it were adopted (cf. Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, 236−40).

At this point, the fate of the world was perceived to be embodied by the bodies of the dead chiefs (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi, Renfrew, Boyd and Morley2015, 271–4). Beyond this, the mortuary communicative domain reproduced through their mortuary ceremonies, including the construction of gigantic keyhole tumuli, became the dominant religious communicative domain where the uncertainties and risks generated by the world, not an animistic one occupied by equally vital and mutually connected living and non-living beings, but the one that is the synthesis of hierarchically classified natural and socio-cultural uncertainties and risks. Here, the hierarchy that was developed throughout Phase 2 was reacted to and processed in a monumental manner, the details of which were hidden from the view of the commoners. The chief was the embodiment of the world, and her/his presence was now signified in a truly monumental form, to be seen and experienced by the whole community. Now, the whole community would have come to feel that it was being watched over and protected by the dead chief and his or her successor(s), reacting to and processing the uncertainties and risks of the world on behalf of all.

At this point, the hierarchical top of the sources of uncertainties and risks became occupied by those generated through the maintenance of interactions with the other communities distributed across the vast EKNH and beyond and their reactions and processing were conducted through the reproduction of the mortuary-religious communicative domain formed and structured around the body of the ‘communal’ chief.

The Later Kofun period through the Asuka period (‘Phase 4’: c. ce 500–650)

The decline and eventual cessation of the construction of keyhole tumuli characterized this phase. The monumental display with the keyhole tumulus of the operation of the religious communicative domain was replaced by Buddhist temples during this phase.

The cessation of the construction of the keyhole tumulus, around the sixth century ce, coincided with the establishment of a centralized hierarchy that replaced the alliance/confederacy of local polities characterizing Phase 3 (cf. Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, 297−320). This is, among other types of evidence, indicated particularly clearly by subtle differences in certain material items distributed by the central authority and deposited with dead local chiefs and leaders as grave goods. Izumi Niro has shown that the formation of a pyramidal hierarchy can be clearly recognized by the differences between (a) those buried with a sword, often with a gold-gilded, decorated hilt; (b) those buried with equestrian gear and/or a sword without a decorated hilt; (c) those buried with arrowheads; and (d) those buried without grave goods (Niro Reference Niro1983). These differences clearly show the increasingly fixed nature of the hierarchical relationship between the giver and the receiver of such items, with the latter, the local chiefs, becoming increasingly detached from their fellow community members. The above phenomenon is likely to have represented the diminishing significance of the communally shared sense of uncertainties and risks that were reacted to and processed by the chief on behalf of her/his (increasingly his) fellow community members. The diminishing significance of the sense of commonality, as shown below, holds a key to the understanding of the implications of the introduction of Buddhism (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, ch. 11).

During Phase 4, the elite became increasingly unconcerned about the well-being of their respective communities and instead focused on more diverse and specialized matters. The individual elites, both of the centre and the peripheral regions, were now assigned increasingly specific tasks by the paramount chieftain (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, ch. 11). According to historical research, by the end of the sixth/early seventh century, the elite of different powerful clans residing in the present-day Nara and Osaka prefectures where the seat of the paramount chieftain was located were assigned specialized roles in governance and the running of the court (e.g. Kumagai Reference Kumagai2001, 183−9). While they were still responsible for the well-being of the members of their respective clans, their worldly concerns were increasingly focused not only on their own survival, which required the successful completion of their assigned roles amid the ever-intensifying power struggles in the court, but also on the running of the emergent state under their governance. These domains presented the elite with a range of novel uncertainties and risks, including those generated from dealings with polities in the Korean peninsula, including militaristic interventions (Kumagai Reference Kumagai2001, 249−51).

The introduction of Buddhism into the archipelago is widely recognized to have resulted from the emergent governing class's desire to emulate the world religion pursued by the Shui dynasty of China and the Koguryo and Shilla kingdoms of the peninsula. These peoples were rivals of the unified polity developed out of the Kofun period confederacy of regional chiefdom-type polities on the periphery of the sphere of Chinese intervention and influence (e.g. Inoue Reference Inoue1974, ch. 5). This inference has been largely verified. In addition, competition with and attempts to gain control over those peninsula polities would have required the authorities to evaluate (and discredit) their deeds by referring to a unified and universal value system. Buddhism would have functioned as a universal system of reference for this kind of value judgement. However, the fact that the essentials of Buddhist teaching also aligned with the rising need for the elite to forge connections and deal with a world of uncertainties and risks that had become much wider and deeper than their former parochial communal concerns cannot be ignored. In other words, Buddhism would have taught the individual elite how to act as individuals living individual lives in the world (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, 321–5).

The oldest Buddhist temple with a fully excavated central complex is the Asuka-dera (or Hoko-ji) temple, built between the end of the sixth century and the beginning of the seventh century ce (Kumagai Reference Kumagai2001, 207–11). The pagoda of this temple, which supposedly contains the bones (called Shari) of the Buddha in its foundation platform, was surrounded by three Kon-do [golden halls] installed with Buddhist images. The halls were enclosed within corridors, and its main gate opened to the south. The Ko-do [lecture hall] was situated right outside the enclosure to the north (Kumagai Reference Kumagai2001, 207–11). Based on the line of interpretation followed in this study, it is important to note the positioning of the pagoda—placed in the centre of the complex; hence, it is awarded the highest significance. The pagoda was designed to symbolize the once physical existence of the Buddha and embody his personal enlightenment, which is why it contains his physical remains. When it was excavated, the remains, the Shari, at the Asuka-dera were revealed to be a combination of coloured glass and crystal beads, deposited with other types of personal accessories, weapons and pieces of armour; resembling, as an assemblage, the typical Late/Final Kofun period grave goods assemblage. Kimio Kumagai compares the significance attributed to the pagoda with the Kofun mortuary practices and suggests that the pre-existing custom of worshipping ancestral spirits, which was widespread in the Late Kofun period, characterized the way in which Buddhism was introduced in the archipelago (Kumagai Reference Kumagai2001, 207–11). However, what appears to be more important is the fact that the significance of the pagoda gradually came to equal that of the Kon-do and the Ko-do in the configuration of the temples built subsequently. The changing trends included shifting to building two pagodas instead of one, as decorative additions to the main Kon-do in the Yakushi-ji type, built at the turn of the seventh century (Uehara Reference Uehara, Kondo and Yokoyama1986). In addition, the Ko-do became incorporated into the enclosure. This process suggests that the most significant spot of the temple shifted from where the physical remains of the Buddha were to the contents of his teaching, embodied by the configuration of Buddhist images inside the Kon-do and the lectures conducted in the Ko-do. In the seventh century, it became increasingly important to gain an understanding of the way in which individuals could achieve enlightenment (Mizoguchi Reference Mizoguchi2013, 321–5).

The increasing importance of Buddha's teachings reflected by changing spatial structure/organization of Buddhist temples symbolized the doctrinization of the way the religious communicative domain was reproduced and the methodologization of the way the uncertainties and risks of the world were reacted to and processed. Now, the uncertainties and risks of the world appeared to individuals, as far as the elite class is concerned, as assemblages that were different among them, and the individual was tasked to cope with the weight of the world by committing to the religious communicative domain in a doctrinized/methodologically specified manner.

Concluding remarks

This article

• recognized that religious practices form a distinct communicative domain;

• defined the character and function of such domain; thus, it reproduces itself in a self-referential manner by referring to a distinction between familiar and unfamiliar and between this world and the other world, and it allowed human groups to respond to and process the uncertainties and risks generated by the world (where the world comprises society and the environment as the totality of possibilities and potentialities for human thoughts and deeds); and

• explained the long-term transformation of the religious communicative domain as the result of changes in the way it mediated/helped/directed people in their reacting to and processing of the uncertainties and risks generated by the world.

To summarize the outcome of this case study briefly, the state of archaeological material exemplifying each phase is italicized.

In Phase 1 (from the Initial through to the Final Jomon period of the Japanese archipelago), the uncertainties and risks generated by hunting and gathering-based ways of life were seasonally changing and not hierarchically distributed in their spatio-temporal constellation. They were reacted to and processed by the religious communicative domain which rendered the relationship among different categories of living and non-living creatures/material differences perceived as fluid, interpenetrating and interchangeable (i.e. animistically interconnected). This was embodied by various material items such as pottery on which various living and non-living beings were depicted as mutually interpenetrating with no clear boundaries between them.

In Phase 2 (the Yayoi period), the uncertainties and risks generated by a rice paddy-field farming-based way of life were hierarchized as the most serious uncertainties and risks. They were reacted to and processed by the religious communicative domain, which explained the genesis and the (hierarchical) order of the world, instructing people about how to follow such an order. The acceleration of this trend led to the esotericization of the contents and media of the religious communicative domain and the establishment of the priest-chief-type figures as the specialist/expert conductors of related acts and exclusive owners of related knowledge. Various living beings, including insects, amphibians, other mammals and human beings as well as tools and buildings were depicted and at times situated in a clearly sequential-evolutionary-hierarchical order. Further, the depiction of the scene of religious-ritualistic conducts also emerged.

In Phase 3 (the Final Yayoi through the Earlier Kofun period), the stylistic formalization and exaggeration/monumentalization of the content(s) and material media of the religious communicative domain, further stimulated by the formation of a vast network horizon within which an increasing amount of goods/resources, information and people moved around/were exchanged and circulated, culminated in the emergence of the keyhole-shaped tumulus as a dominant locale for the reproduction of the religious communicative domain.

Phase 4 (the Later Kofun period through the Asuka period) witnessed the introduction of a ‘world religion’: Buddhism. This coincided with the elite becoming increasingly detached from the concerns of their respective communities, rather concentrating on more diverse and specialized matters. Individual elites were now assigned increasingly specific tasks by the paramount chieftain. This trend led to the deconstruction of the communal mode of reacting to and processing the uncertainties and risks generated by the world and the individualization, methodologization, and doctrinization of such a mode, embodied by the spatial structure/organization of Buddhist temples.

The procedural framework that this article has proposed, that is, a three-stage investigation-reconstruction of the way a society responded to and coped with the uncertainties and risks they faced by differentiating, mobilizing, connecting and separating certain mental and material phenomenal units (see above), as the case study shows, enables us to explain how the long-term sequence of punctuated drastic changes in the way practices were conducted and in the assemblage of mental and material phenomenal units involved in/mobilized for their conduct came about, in fact, regardless of such practices being recognized as religious or otherwise. This concrete procedural framework can be further developed and refined by applying it to cases from different regions of the world and different temporal phases of the world in pre- and proto-history.

Acknowledgements

I thank two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions. I also thank the late Sarah Nelson, Fumiko Ikawa-Smith, Gina Barnes, Junko Habu, Simon Kaner, Mark Hudson and the late Leo Aoi Hosoya for their encouragement and advice over three decades in situating my work on Japanese pre- and proto-history in the landscape of world archaeology. Any shortcomings are my responsibility. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant no. JP20H01350).