Introduction

As human beings, we move through different tempi and temporalities. All human beings engage actively with the past, but in highly varying manners. Independent of whether people are trying to detach themselves or relate and attach to the past—or rather pasts—these are used physically and materially. This detachment or connection can also refer to reference points from which the past is reintroduced (Jones Reference Jones2007). Noticeably, these reuses and reintroductions and renaissances always contain a transformation of the old. Similarly, when a memory appears, it always includes a transformation. When we recall and remember, it is not the old memory that is being recalled; in the process of remembering, a link to a new memory is created (Olick Reference Olick1999, 340). This change that takes place through the memory of past actions and events is always something on its own terms, a transformation of that which is remembered (Gadamer [Reference Gadamer1960] 2001, 270–311). In other words, a reuse is not simply a repetition, but an alteration. In prehistory this may, for instance, act out through a reburial in an older mound, when structures of the past are being reused, when old forms and types are being recycled, and when artefacts produced centuries earlier are being kept, managed and engaged with newly produced objects.

In Viking Age Scandinavia, the past appears to have held significant importance. Within Scandinavian Viking Age archaeology, the use of the past (or rather pasts) has been studied primarily through burials, in particular the reuse of mounds and the occurrence of antiquities in the graves (Andrén Reference Andrén2013; Artelius & Lindqvist Reference Artelius and Lindqvist2005; Arwill-Nordbladh Reference Arwill-Nordbladh, Pettersson and Skoglun2008; Fahlander Reference Fahlander2018; Reference Fahlander, Aspöck, Klevnäs and Müller-Scheeßel2020; Glørstad & Røstad Reference Glørstad, Røstad, Vedeler and Røstad2015; Hållans Stenholm Reference Hållans Stenholm2012; Lund & Arwill-Nordbladh Reference Lund and Arwill-Nordbladh2016; Williams Reference Williams, Alexandersson, Andreeff and Bünz2014). In his review article of the field, Anders Andrén (Reference Andrén2013) points out that memory clearly played a vital role in Viking Age Scandinavia, as testified by the raising of rune stones, the reuse of graves and the use of material objects as vehicles of remembrance. Furthermore, the commemorative aspects of rune stones, their effects and affects and their references to past traditions have been explored (Danielsson Reference Danielsson2015; Lund Reference Lund2020). As within identity studies in Viking Age archaeology, cultural memory in relation to migration has also been enhanced by these studies (Naum Reference Naum2008; Roslund Reference Roslund2001). Based on a study of British Roman period objects, Chris Gosden (Reference Gosden2005) has identified how object types may affect the construction of new object types, and thus turned attention to how specific forms might invite these creations. Similarly, the ways in which a form, or what we today may define as a typology, was kept and maintained has been explored in research on Viking Age coins (Burström Reference Burström2014) as well as on pendants, where some object forms reappear and make reference to object types that are 600 years older (Arwill-Nordbladh Reference Arwill-Nordbladh, Pettersson and Skoglun2008). Scholars working with Anglo-Saxon England have also pointed out the intensive use of and references to the past, linked to pre- and post-conversion conceptualities of the landscape (Lund & Semple Reference Lund, Semple, Lund and Semple2020; Reynolds Reference Reynolds2009; Semple Reference Semple1998; Reference Semple2013; Williams Reference Williams1997). Thus, clearly the use of the past also played a part in how humans understood and conceptualized the world in which they lived. In the following, the theoretical foundation for reassessing the past in the Viking Age will be explored via an attempt to address the use of kerbstones on mounds in several eastern Norwegian cemeteries as a way of dealing with time depths. These approaches to time and temporality, studied through the use of kerbstones, may provide insights into how the past was perceived in the Viking Age. Moreover, Norwegian kerbstones and their potential ability to work with humans across time may reveal a relevance beyond Viking Age studies. Superficially insignificant as they are, in this context kerbstones can be used as a catalyst for opening the range of materials considered in temporal approaches in Viking Age studies. As will be demonstrated, use of the past in the past has often been studied through the lens of power strategies. However, in this paper other threads will be followed, exploring reuse in the light of affectivity and of the construction of relations across time with the ambition to approach how materials, structures, humans and memories may work on each other across time.

Reassessing the pasts in the past

The use of the past was accentuated as a theme at the beginning of the 1990s as part of the examination of the cultural landscape, particularly within British archaeology. The theme was unfolded within various rather different studies that shared a focus on the use of monuments, predominantly from the Neolithic period and the Bronze Age (Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Bradley and Green1991; Bender Reference Bender1993; Bradley Reference Bradley1993; Thomas Reference Thomas and Tilley1993; Reference Thomas1996). In addition to sharing an emphasis on spatial analyses, in terms of the landscape perspectives these studies were closely connected to the metaphors of reading material culture as text, including Roland Barthes’ famous notions of the death of the author. This led to a focus on how different human beings could have diverging ideas of the same monument, depending on their social roles, and an appreciation of how the constructors of a monument could not necessarily predict how the monument would function or be perceived by future generations (just as the author could not foresee the reader's experience of a text). The inherence of post-processualism, in terms of perspectives on how diverging social groups may have perceived the same landscape differently, also made a significant contribution. The use of the past was further explored as a phenomenon, in particular in the research of Richard Bradley (Reference Bradley2002) and Laurent Olivier (Reference Olivier2004; Reference Olivier2011). Whereas the contribution of the first included an appreciation of how the use of the past in relation in particular to monuments include a development of a sense of place, the latter drew our attention to the fact that the past (or rather pasts) are always physically present in the present, in our immediate surroundings in terms of the buildings, roads, pieces of furniture, books, and the entire material world, i.e. in our present environments. Thereby, indirectly studies of the use of the past also emphasize the closeness of archaeology and heritage studies. The use of the past in the past was a distinct part of the post-processual and interpretive archaeology wave, but as a field of study it was more or less abandoned in the following decades (Lund & Sindbæk Reference Lund and Sindbæk2021). However, several perspectives introduced in other parts of archaeology may strengthen the need for renewed attention to the use of the past in past societies. In this manner, the phenomenon of reuse is synchronized with other aspects of the human pasts that have been reassessed in recent years, in terms of a focus on capacities of material culture, the attention to relationality in archaeology and the consequences of what has been termed the affective turn.

Archaeological examinations of assemblage theory have turned our attention to the relational aspect in the construction of assemblages and their acts on other units (Fowler Reference Fowler2013; Jervis Reference Jervis2019; Lucas Reference Lucas2012). In contrast to materiality studies, which put their weight on the properties of material culture, studies of assemblage have shifted the focus to include the capacities of artefacts as well as of assemblages (Fowler Reference Fowler2013). Here, it is central to differentiate between the properties and the capacities of materials and material culture. The properties relate to the qualities of the materials and objects, and can be accessed through a study of these qualities, whereas the capacities are forces which may be activated or not activated at various times and contexts, and are thus dependent on the properties of the object, but also of the relations that they are part of. Attention on capacities allows us to notice effects caused by the use, or mere presence, of specific objects. In addition, using the past is about relationality (Fowler Reference Fowler2017). As artefacts, forms, structures, or sites are being reused, a physical or referential relationship is being created. This connection moves across time. Furthermore, in recent years, studies of the sensuous effects and emotions have been brought into archaeological research (Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2013; Harris Reference Harris, Sørensen and Bille2016; Tarlow Reference Tarlow2012). This has brought forward an awareness of the physical bodies of humans of the past and their reactions toward material culture. Yet this paper will attempt to give attention to aspects of affect that moves beyond studying senses and emotion only, in line with a number of recent studies (Crellin & Harris Reference Crellin and Harris2021; Jones Reference Jones2020; Jones & Cochrane Reference Jones and Cochrane2018). Several scholars have identified how a study of not only the material qualities of artefacts and structures, but also their potential affect, may give insight into how we may approach the interaction between humans and objects and its potential relations. These perspectives put weight on materials or archaeological remains to be affective on their own terms in ways which are clearly historically situated (Alberti et al. Reference Alberti, Jones and Pollard2013; Crellin & Harris Reference Crellin and Harris2021; Danielsson Reference Danielsson, Alberti, Jones and Pollard2013; Danielsson et al. Reference Danielsson, Fahlander and Sjöstrand2012; Jones & Cochrane Reference Jones and Cochrane2018). These perspectives, with their attentiveness towards affective capacities and relationality, can be helpful for understanding the consequences of reusing and reassessing material culture.

Folded time

In addition to an appreciation of capacities, relations and affects, a comprehension of uses of the past in the past also calls for a perception of how time works. One way of approaching this is through the concept of folded time. The concept of topological folding is based on the work of Michel Serres, and has previously been used in Viking Age studies to explore the ways in which past and present met at specific locations. These studies opened up an understanding of time which was not simply linear. Rather, these studies pointed out that, through rediscovery and return to the same location, the clear distinction between past and present was blurred. As Ing-Marie Back Danielsson points out, the reconstructions of person from the late Viking Age may lead to the existence of a multitemporal figure, in which time may be perceived not as linear, but as folds. Similarly, re-engagement with the same site or place may, as Elin Engström points out, constitute itself as an occurrence, within which time folds (Danielsson Reference Danielsson, Bohlin and Gemzöe2016a, 196–7; Engström Reference Engström2015).

The philosopher Gilles Deleuze's notion of folds may theoretically be of use here, as it represents a reflection of the manners in which matters disclose themselves over time, exploring how and if an event may endure (Deleuze Reference Deleuze2015). As Deleuze points out, even when the same type of action appears as a repetition, such as the blow of a hammer on an anvil, each blow differs. So, even when a similar action takes place, or a similar piece of material culture appears, it is different from the previous and the following. The similarities can thus never explain the singularities (Deleuze Reference Deleuze1994: see also Williams Reference Williams2011). We may ask ourselves how the singularities of each of the instances elude each other despite the overwhelming similarities. In other words, if the same type of material culture is in use in two different time spans, and are thus reactivated and reused, how may we perceive this similarity of use? These notions may only indirectly appear to apply to the conditions of the archaeological record. It does, however, raise questions of what reuse of material culture is. Further, the concept of the fold may be useful in relation to time, where the use of the past may be compared by analogy to the physical phenomenon, such as those of the folding Caledonian mountains. Parts of Scandinavia are part of the Caledonian mountain range. These mountains were folded in the Caledonian orogeny in the Ordovician to Early Devonian period. Mountain foldings such as these were produced as the old bedrock was pushed downwards, which brought the older oceanic crust eastwards and placed it on top as a thrust fault. What makes the Caledonian folds relevant as an analogy for the uses of the pasts in Viking Age Scandinavia is that it breaks with the conceptual perspective of time as linear in its physicality. It reminds us that we are constantly surrounded by physical structures which are much older than our presence and that their time can be read as not being linear (se also Olivier Reference Olivier2011). The past is, in other words, present here and now. As Gavin Lucas points out (Reference Lucas2005), building on the philosophy of Husserl, archaeological material is essentially multitemporal. In addition, it reminds us that a linear conceptualization of time is not always the most relevant. These conditions were also premises during Viking Age Scandinavia.

Power, agency and affects—what is acting upon what?

The studies of reuse in the Viking Age have been interpreted as expressions of a power strategy in which the claiming of ancestry came into use as a means to gain or maintain power (see for instance Bill & Daly Reference Bill and Daly2012; Christensen et al. Reference Christensen, Baastrup, Gelskov and Nielsen2015, 149; Pedersen Reference Pedersen, Andrén, Jennbert and Raudvere2006; Skre Reference Skre and Skre2007, 466; Thäte Reference Thäte2007). Generally, within Viking Age archaeology, interpretations of the construction, acquisition and maintenance of power tend to be built upon a structural Marxist conception of power in which power was believed to be maintained through the control of status objects. These notions also contain the idea that power was constructed through a deception performed by the social elite toward the lower social layers. This interpretational framework includes the use of the past as a means of manipulation by the elite (Lund & Sindbæk Reference Lund and Sindbæk2021; for a similar critique of the use of the power concepts within archaeology in general, see Crellin & Harris Reference Crellin and Harris2021). These interpretations of the use of the past as a power strategy thus built upon the premise that a scheming elite managed to construct links to past monuments in order to remain in their social position. Yet, already with the concept of power in Michel Foucault's writing in 1982, this perception of power was defied, as Foucault demonstrated that power only occurs when it is accepted by the party who is lowest in the hierarchical relationship (Foucault Reference Foucault1982). This insight also challenges the perception of the use of the past as a power strategy. Foucault's notions of power have other challenges, however. As Lynn Meskell (Reference Meskell1996, 8–9) points out, by presenting power as inscribed on bodies through discursive discipline, Foucault undervalues the active corporality of the body. She points out the limitations of the models of domination (and resistance) in which the focus has been on power strategies, which take for granted that all-consuming energy and labour is invested to maintain a position of power. With such a simplification of the social dynamics, the relevance of studying the life experiences of the individuals involved is overlooked and underestimated (Meskell Reference Meskell1996, 8–9). By examining the use of the past in a specific context of time and space, we may gain insights which take us beyond power balances. We may gain an understanding of how various social groups actively created relations to phenomena from the past, and in other cases how they, through deliberate oblivion, rejected specific features from the past. Such studies may provide us with an understanding of how time was perceived in this context. These elements are part of fundamental aspects, such as the identity of a social group, as pointed out in research on cultural and collective memory (Assmann Reference Assmann1995; Connerton Reference Connerton1989; Nora Reference Nora1989), and also of how people perceived the world in which they live; in other words, in ontology. Furthermore, an active use of the past consists of the creation of relationships between the past and the contemporary. Thus, a study of the use of the past is an examination of which types of connectedness were considered relevant in a specific context.

The simplistic approach to power in previous studies of the past in the past and in archaeology in general has, in the last 15–20 years, been replaced by, but potentially also given way to, the agency debate (see for instance Barrett Reference Barrett, Robb and Dobres2000; Dobres Reference Dobres2000; Robb Reference Robb, Renfrew and Bahn2005). The potential agency of objects entered the forefront of the archaeological discourse (with perhaps Gosden Reference Gosden2005 as the prime example). This debate has, however, also turned into a game of Old Maid, in the sense that focus is on ‘who has it’ rather than on the effects of agency and on how the game moves around the table (Fig. 1). The current affective turn (see, for instance, Danielsson Reference Danielsson, Alberti, Jones and Pollard2013; Jones & Cochrane Reference Jones and Cochrane2018; Pethick Reference Pethick2015) may have the potential to direct the attention from the actants and from the cards to the game, so to speak. A focus on affects, or what in Germanic languages would be described as Einwirkungskraft, allows us to look into how things work on each other and with what forces. Rather than asking what the agency of, for instance, a phenomenon such as kerbstones is, we may question how kerbstones affected humans in the past, what activates them, and why they are more relevant in some periods than others. It is through physical engagement with human beings that objects can evoke memory (Jones Reference Jones2007, 22–6). By acknowledging that affects are embodied states, and through studying material objects’ affecting presence in the present, we may identify traces of emotional experience in the past (DeMarrais Reference DeMarrais2013, 103). Furthermore, these affects do not solely deal with emotions and sensuous aspects of past lives; affects contain the influences that objects may have had on humans in the past. In some instances they may even be prime or relevant movers of actions, as will be explored in the following, where I will argue that kerbstones were used on a small group of Viking Age mounds due to the kerbs’ capacity to mediate ‘a sense of the past’. As the past was actively used through various types of material culture in Viking Age Scandinavia, from small objects to whole landscapes of monument (Lund & Arwill-Nordbladh Reference Lund and Arwill-Nordbladh2016; Lund & Sindbæk Reference Lund and Sindbæk2021 with references), an attempt will be made in this analysis to explore how and why this was a desirable capacity for these kerbstones at this specific site during the Viking Age.

Figure 1. (Left) the Old Maid card from the game of Old Maid; (right) the Scandinavian and northern German version, the game of the cat ‘Black Peter’. The author claims that the focus in the agency debate has been on ‘who has it’ rather than giving attention to the effects and movement of the game (of social interaction) itself. (Thomas Rowlandson, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons & Julie Lund.)

Kerbstones. Connections to the past?

The use of kerbstones has a long tradition in south Scandinavia. In the Neolithic period, kerbstones were used in megaliths, as they were placed around the long mounds that covered a dolmen (Dehn Reference Dehn, Laporte and Scarre2016, 65–6; Midgley Reference Midgley2008, 51–6). Kerbstones surrounding burial mounds were also in use in the Bronze Age in these regions. In the Bronze Age the kerbs were partly hidden or covered by the barrow. One of the most detailed examinations of the construction of Bronze Age mounds is at Borup Eshøj I, where the kerbstones had two different construction phases, consisting of an inner stone platform and an outer, later stone pavement partly built of plane stones; but this was only visible for an intermediate phase during and possibly prior to the construction of the mound (Frost et al. Reference Frost, Løvschal, Lindegaard and Holst2017, 1–12). Thus, the kerbs were only known to the people who took part in or were present at the construction of the mound, and thereby the hiding of the kerb was part of the process of constructing the mound. Yet the kerbs from the Bronze Age mounds became visible when the mounds were worn down, as water and gravity caused erosion. Thus, in later prehistory a visible kerb in south Scandinavia could indirectly bear witness to the old age of the mound. The use of kerbs does, however, vary regionally. In Østfold, eastern Norway, most mounds with kerbstones originate from the Roman and Migration periods (Løken Reference Løken1974a; Petersen Reference Petersen1916; Resi Reference Resi1986).

The mounds with kerbstones also appear to have attracted new burials in the Viking Age. An analysis of kerbstones from Early and Late Iron Age in Vestfold and Østfold, Norway, shows clearly that there is no link between the size of the mound and the presence or absence of kerbstones. It has been claimed that the kerbstones are purely functional, meant to prevent the soil from eroding from the mound (Andersen Reference Andersen1952). However, other scholars have pointed out that the kerbstones are not necessary for the construction of the mound (Løken Reference Løken1974a, 153–4), as mounds with and without kerbs do not show any other diagnostic differences. In other words, there is no purely functional explanation for the kerbstones. Potentially, the use of kerbstones surrounding the Iron Age mounds might be citing the Bronze Age mounds through the use of kerbs, this time not inside, but instead at the foot of the mound (se also Jones Reference Jones2007 for an additional discussion of citational fields; and Lund & Arwill-Nordbladh Reference Lund and Arwill-Nordbladh2016 for an example of usage within Viking Age mortuary archaeology). However, as Bronze Age mounds do not dominate the same regions in Scandinavia as Iron Age mounds, such references would be to mounds in other regions. Though of varying sizes of stone, in general the use of kerbstones shares properties across time. They are stones placed to mark the expansion of the mound and they demarcate the extent of the mound. Across time they denoted what (in terms of exterior as well as content) was inside it, and what was not.

Kerbstones in Østfold, Norway. A Viking Age phenomenon?

The 6000 graves from the Viking Age make up on of the largest groups of prehistoric finds in present-day Norway. Few of these finds are from larger cemeteries, but are mostly found as single monuments or in small groups of graves (Solberg Reference Solberg2003). The Østfold region in southeast Norway is, however, dominated by a few large cemeteries with long continuity, including Hunn and Store-Dal. Around 270 graves from the Viking Age have been found in Østfold (Pedersen et al. Reference Pedersen, Stylegar and Norseng2003, 338–9). The outer structures of these graves are divergent, and may consist of stone settings or more commonly a mound, but also include burials without outer structures. The interiors of the graves are also highly varied, and these include cremation as well as inhumation graves (Lund Reference Lund2013). During the Viking Age, diverging types of burial rituals were practised (Lund Reference Lund2013; Price Reference Price2010; Reference Price2014). Kerbstones are a common feature on Norwegian Iron Age mounds. Trond Løken has made the largest comprehensive examination of burial traditions and the grave mounds from Østfold and Vestfold in eastern Norway. On the basis of this analysis, Mari Østmo has pointed out that the use of kerbstones around the round mounds was not unusual in the Late Iron Age, which includes the Merovingian period and the Viking Age, thus lasting from approximately 550 to 1050 ad (Løken Reference Løken1974a,Reference Løkenb; Østmo Reference Østmo2005). A closer examination of these analyses demonstrates that most of the Late Iron Age mounds that had kerbstones in Østfold were from the Merovingian period and not the Viking Age. According to Løken, 10 per cent of the Late Iron Age round mounds in Østfold had kerbstones (Løken Reference Løken1974a,Reference Løkenb). This low number may be even smaller, if we examine its foundation: a detailed study of the burial mounds from Østfold shows that only a very few of them—six round mounds from the Viking Age with kerbstones—can be identified. These mounds are located at Hunn, Store-Dal and Store Tune in Østfold (Løken Reference Løken1974a). The presence of kerbstones on these mounds and their potential to create references and connection to pasts will be examined, as it will be argued that they may have been used in the Viking Age to construct a sense of age. Whereas creation of mounds in itself bore a referential element to the past in the sense that it was an ancient tradition, and whereas the reuse of mounds was a common phenomenon in the Viking Age (Artelius & Lindquist Reference Artelius and Lindqvist2005; Hållans Stenholm Reference Hållans Stenholm2012; Pedersen Reference Pedersen, Andrén, Jennbert and Raudvere2006; Thäte Reference Thäte2007), the use of kerbstones was, in other words, an unusual means of creating a link to the past.

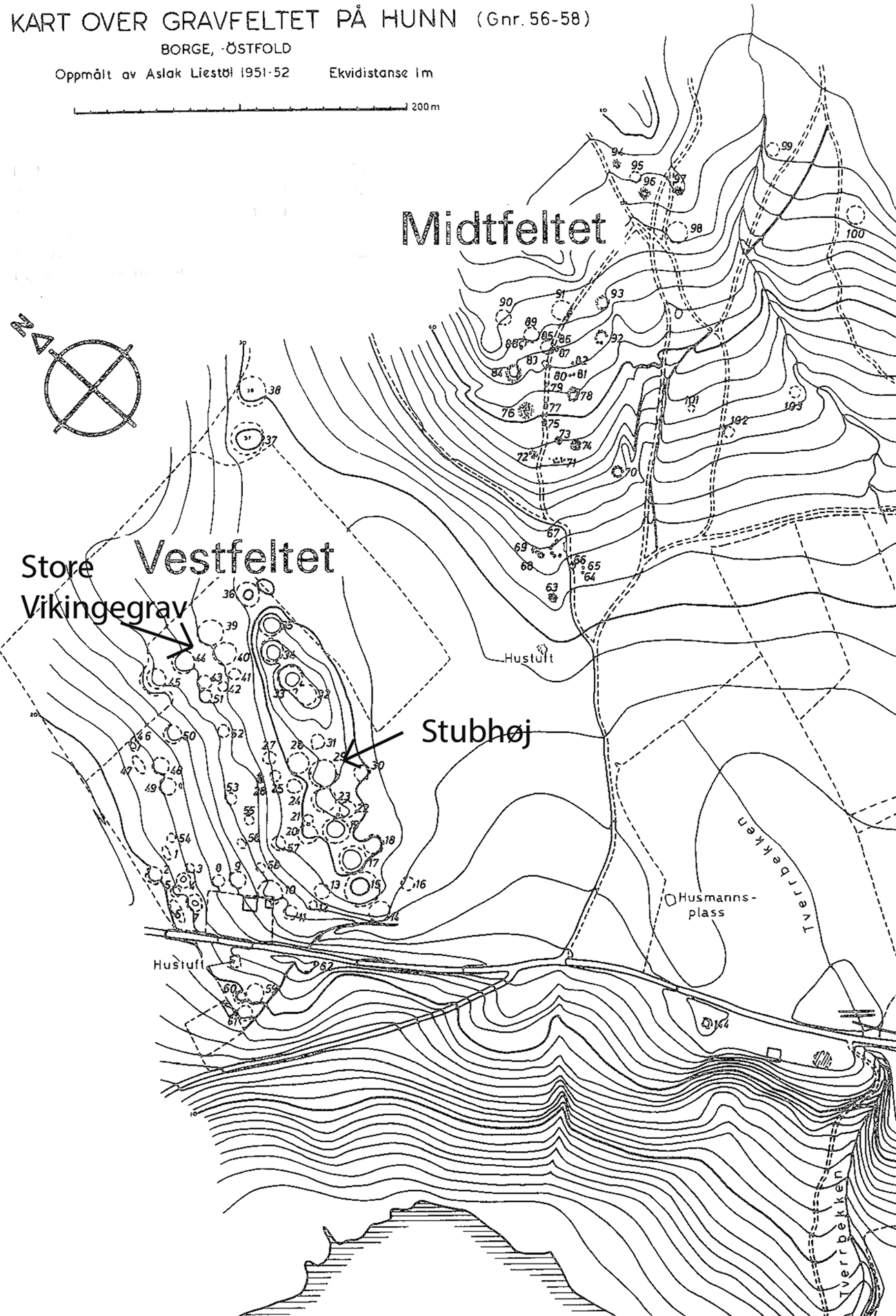

Kerbed mounds at Hunn

The cemetery at Hunn, Borge, in Østfold consists of no less than 145 visible burial mounds, of which 57 have been archaeologically excavated. The total number of burials is unknown. The site has an unusually long continuity of use from the Late Bronze Age to the Viking Age (1100 bc–ad 1050) with burials in all the periods in between (Resi Reference Resi1986; Reference Resi, Østmo and Hedeager2005). The burial custom is almost exclusively cremations, but three Roman period graves (1–400 ad) and three Late Iron Age graves (550–1050 ad) are inhumation graves (Resi Reference Resi1986). The cemetery has three clusters, termed respectively Vestfeltet, Midtfeltet and Sydfeltet (West, Mid and South fields). The Vestfeltet contains Roman period and Migration period graves (ad 1–550) in particular, but was generally in use during the Iron Age (500 bc–ad 1050). The interiors of the burial mounds show a clear division between mounds from the Roman period from Hunn, which contain a central cairn covered with soil, whereas the burial mounds of the Late Iron Age, including the Viking Age (ad 550–1050) consist of soil exclusively (Resi Reference Resi1986, 13). The majority of the Roman period mounds have regular kerbstones (Resi Reference Resi1986, 14). Only two of the kerbed moundsFootnote 1 are round mounds from the Viking Age: F.48/A.L.50 ‘Store Vikingegrav’Footnote 2 and F.44/A.L.46 (Fig. 2). These two mounds are located in the Vestfeltet (West Field) of the cemetery, placed next to burial mounds from the Roman period. The first of these mounds shows elaborate similarities to a much older mound at the same site, the mound F.19/A.L.29 ‘Stubhøj’. These mounds will be described in detail, in order to grasp the resemblances between these graves across time.

Figure 2. Map of the Vestfeltet and Midtfeltet cemeteries at Hunn, Easter Norway. (From Resi Reference Resi1986, pl. 70.)

The round mound F.48/A.L.50 Store Vikingegrav was surrounded by kerbstones of tightly placed, angular stones in a wall-like structure. The kerb was not removed during excavation and is still located in situ (Fig. 3). In the centre of the grave was the remains of an osteologically poorly preserved inhumation grave with a large number of objects which could typologically date the grave to the Late Viking Age (Resi Reference Resi1986, 83). The grave goods included a sword, an axe, a shield, spurs, two drinking horns, whetstones, a steatite bowl and iron-bronze fragments, which have been interpreted as the remains of a penannular brooch. The vast majority of graves with weapons are male graves (though notice Hedenstierna-Jonson et al. Reference Hedenstierna-Jonson, Kjellström and Zachrisson2017 (with references); Moen Reference Moen2010). Most of the penannular brooches from male graves dating to the tenth century ad have been identified as belonging to a social group closely related to the early establishment of kingship (Glørstad Reference Glørstad2010, 90, 114–61, 254–86; 2012). Even the soil from the Store Vikingegrav mound may be examined in order to gain insights into the use of the past at the construction of the grave (for a discussion on the use of soils in the construction of mounds in the Viking Age, see Cannell Reference Cannell2021; Cannell et al. Reference Cannell, Bill and Macphail2020). The soils from the mound contained concentrations of charcoal, ceramics, burnt bones and pottery. Ceramics ceased to be in use in Norwegian prehistory at the transition from the Migration to the Merovingian periods (c. ad 550), centuries prior to the construction of the mound. Thus, the layers used to construct the mound most likely were the remains of a former settlement or grave dating from the period in which the location and pottery were in use, that is, between the Bronze Age and the Migration period.

Figure 3. The F.48/A.L.50 Store Vikingegrav at Hunn, eastern Norway, during excavation with the kerbstone in situ. (From Vibe-Müller Reference Vibe-Müller1951, 168.)

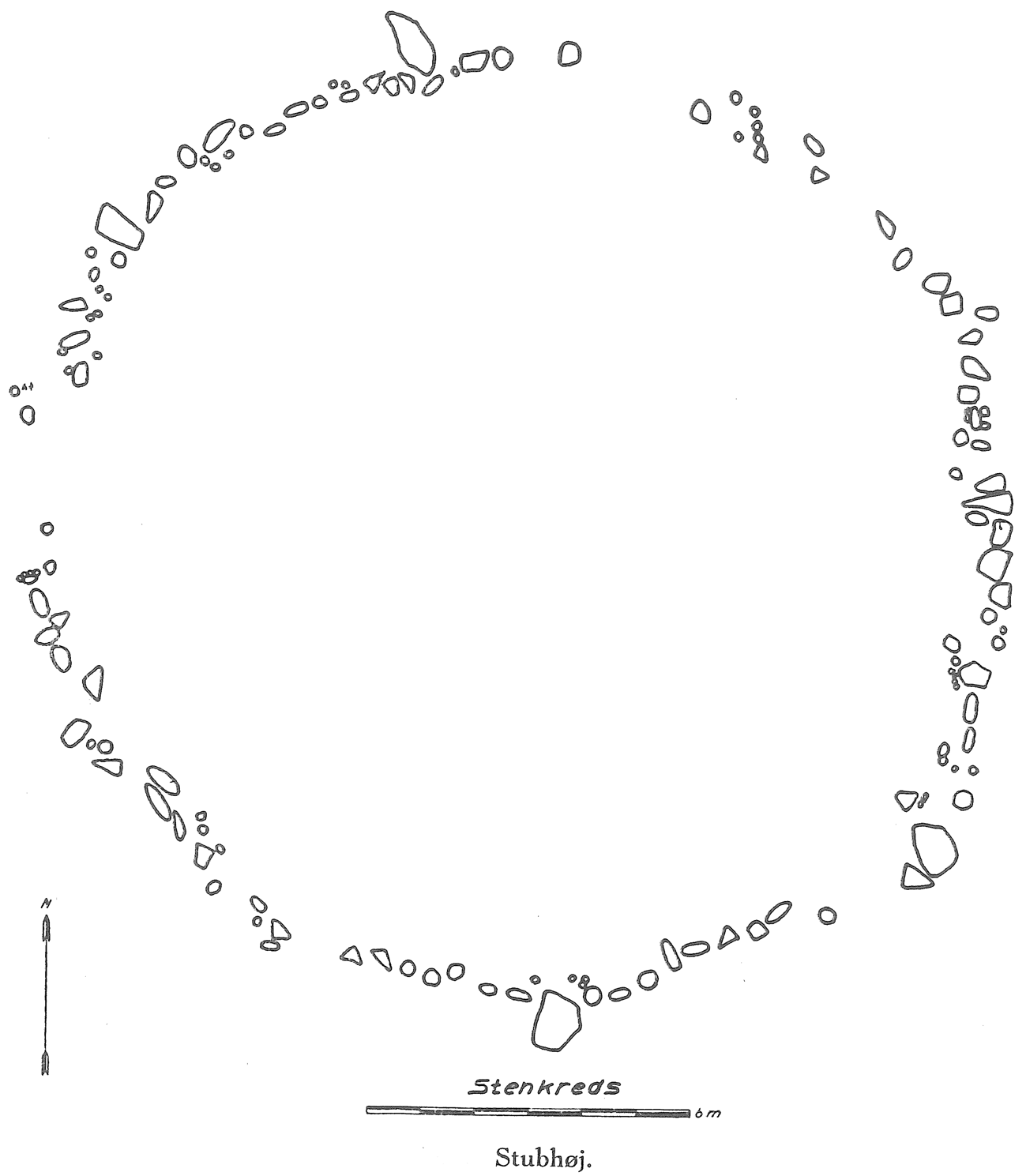

At the excavation of Store Vikingegrav, it was noticed that the kerb of the mound resembled the Roman period mounds at the site (Resi Reference Resi1986, 13–14; Vibe-Müller Reference Vibe-Müller1951) (Fig. 4). Among the Roman period mounds at Hunn was one of the richest graves of early Roman period Norway. In outward appearance, the most significant of the Roman period mounds is this very same mound: F.19, A.L.29 ‘Stubhøj’ (Fig. 5). As Stubhøj has the most significant location on the top of the hill/ridge, and is is the most noticeable point in the sightline, it is the most obvious inspiration for the outer appearance of Store Vikingegrav. Stubhøj mound is located on top of a ridge and is surrounded by a kerb very similar to the kerbstones later placed at Store Vikingegrav (Fig. 6). Even the location of Store Vikingegrav imitates Stubhøj, as it is located on the same slope of the ridge, just below Stubhøj.

Figure 4. The reconstructed round mound F.48/A.L.50 Store Vikingegrav at Hunn, eastern Norway, with the original kerbs in situ. (Photograph: Julie Lund.)

Figure 5. The reconstructed round mound F.19/A.L.29 Stubhøj at Hunn, eastern Norway, with the original kerbs in situ. (Photograph: Julie Lund.)

Figure 6. Drawing of the F.19/A.L.29 Stubhøj at Hunn, eastern Norway, during excavation with the kerbstones in situ. (From Laursen Reference Laursen1951, 144.)

There is also a noticeable resemblance between the interior of the two graves. In the inhumation grave Stubhøj, the grave goods included a sword, a spearhead, a shield, two bronze spurs with silver inlays and gold foil, two drinking horns, a gold finger ring, round and rectangular silver mounts and bronze fragments (Resi Reference Resi1986, 70–72). Stubhøj belongs to the very small group of so-called princely Lübsow graves in northern present-day Poland, Germany, Denmark and Norway containing Roman imports. The Lübsow graves in Scandinavia diverge from the dominating cremation burial tradition in the area in their time (Eggers Reference Eggers1953; Lund Hansen Reference Lund Hansen1987; Resi Reference Resi1986, 200; Schuster Reference Schuster2010). The weapons place Stubhøj as a weapon grave in group 2, consisting of a group of graves believed to have belonged to the social elite (Ilkjær & Carnap-Bornheim Reference Ilkjær and von Carnap-Bornheim1990, 361). If we compare the grave goods of Store Vikingegrav and Stubhøj, we may notice the spurs in particular. Spurs in Viking Age graves are not very common, and only a few have been found in Østfold (Petersen Reference Petersen1951, 36–8). Spurs in Roman period graves are highly unusual. These Roman period spurs from Stubhøj belong to a small group of very high-quality spurs meant for display found in a few graves spread across northern and central Europe (Böhme Reference Böhme1991; Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen1989; Tejral Reference Tejral, Pesla and Tejral2002). They have silver inlay, which could also have made them highly visible in the performance of the funeral ritual (Fig. 7). They are very rare and are typically found in combination with gold finger-rings and Roman imports and are interpreted as the top of the social elite (Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen1989, 184–5; Solberg Reference Solberg2003, 95–6). Furthermore, like Store Vikingegrav, in addition to full weapon equipment and shield, Stubhøj contained two drinking horns, an artefact type which is found exclusively in the small group of well-equipped Roman period graves with Roman imports. As an inhumation grave, Stubhøj displays a marked change in the burial custom of its time. From the Late Bronze Age to the Roman period B2, the custom had been exclusively cremation graves. Stubhøj, and mound 6 in the nearby cemetery of Store-Dal, are the oldest inhumation graves in the Norwegian Roman period. The burials thus break with the burial custom of the previous 1100 years. Overall, the Stubhøj grave and Store Vikingegrav have clear resemblances in the interior of the graves, being inhumation graves with full weapon equipment including shields, the rare occurrence of drinking horns, and the extremely rare occurrence of spurs. Furthermore, the outer resemblance between the Stubhøj mound and the Store Vikingegrav mound is striking. The location in the landscape on the ridge is similar, yet Stubhøj is situated with a better visibility from afar, whereas the best spot for this type of location was already filled with other mounds in the Viking Age (Fig. 2). The kerbstones surrounding Store Vikingegrav are elaborate, at some places almost built rather than laid out, as the excavators noticed; but the size of the stones and the material, the local granite, is identical to the kerbstones on Stubhøj. The similarities between the interior of the Roman period grave and the Viking Age grave are intricate and specific. They may have been known to the participants of the Viking Age burial and for those who shared the oral history of that occasion. Yet, what connected them directly was the exterior of the graves, and in particular the kerbstones. These similarities were available for everyone visiting the cemetery, independently of whether they knew of the content of the burial. Thus it was the use of the kerbstones constructed in such a similar way to the Roman period mound and placed in a similar location in the landscape that created and materialized the relation between the two mounds. By choosing to use kerbstones as a demarcation of the mound, Store Vikingegrav simultaneously differs from almost all of the other known 270 Viking Age graves of Østfold, which most likely are only a fraction of the original number of Viking Age graves in the region.

Figure 7. The spurs with silver inlays from F.19/A.L.29 Stubhøj at Hunn, eastern Norway. (From Laursen Reference Laursen1951, 151.)

The similarities between the two graves are too strong to be coincidence. The resemblance between the two graves, which are separated by c. 600 years, points towards a complex relationship between them. The similarities in the outer appearance of Stubhøj and Store Vikingegrav indicate that the latter was constructed to mimic the former. Andrew Jones’ concept of citational fields is relevant here (see also Danielsson Reference Danielsson2016b; Jones Reference Jones2007; Lund & Arwill-Nordbladh Reference Lund and Arwill-Nordbladh2016; Williams Reference Williams2016, for discussion of citational fields in Viking Age archaeology). Potentially, details of the burial rituals performed at Stubhøj in the Roman period were kept as part of oral history through the centuries in the local communities. The fact that the deceased was buried with a very rare pair of Roman spurs indicate that this could be an individual whose actions were well known in the local community in the lifetime of the buried one. Unique Roman imports were acquired through gift giving between Roman authorities and Germanic tribes or individuals, presumably as part of the creation of alliances (Hedeager & Kristiansen Reference Hedeager and Kristiansen1981; Hedeager & Tvarnø Reference Hedeager and Tvarnø1991; Jensen Reference Jensen2003; Lund Hansen Reference Lund Hansen1987). The acquisition of the spurs could thus be part of an event that had lived on in the oral history of the community of the receiver of the spurs. With such a scenario, the Viking Age burial in Store Vikingegrav could deliberately have been acted out in a manner which bore reference to a distant and mythical, but very specific past (for a distinction between genealogical and mythical pasts, see Gosden & Lock Reference Gosden and Lock1998). A story of an event can live on almost unchanged through approximately 200 years and on occasion up to 500 years (Hedeager Reference Hedeager2011; Schmidt Reference Schmidt and Robertshaw1990; Vansina Reference Vansina1985, 82–91; see also Andrén Reference Andrén1997, for a critical discussion of the relationship between oral history and archaeology). Burial rituals of the Viking Age indicated that aspects of the Old Norse mythology were acted out as part of the mortuary rituals in a manner which has been interpreted as a funerary drama, underlining the performative aspect of the burials (Andrén Reference Andrén1992; Price Reference Price, Hays-Gilpin and Whitley2008; Reference Price2010; Reference Price2014; for a full discussion of the changes in studies of Viking Age graves, see Lund & Sindbæk Reference Lund and Sindbæk2021, with references). Aspects of Late Iron Age myths have been documented to live on through a similarly long time. The myths of the god Týr, whose hand was bitten off by the wolf Fenris, can be identified on numerous Migration period bracteates from Scandinavia and are written down as a pagan myth in thirteenth-century Christian Iceland (Axboe Reference Axboe2004; Hedeager Reference Hedeager, Downes and Ritchie2003; Reference Hedeager2011). Thus it is an example of oral history living on over 800 years concurrently in this part of Europe. Considering how significant the creation of the Stubhøj burial must have been, breaking with an 1100-year-old tradition of cremating the deceased, it is not unlikely that the memory of the burial rituals lived on in the collective memory (Assmann Reference Assmann1995; Connerton Reference Connerton1989; Nora Reference Nora1989). Moreover, as the grave goods included artefacts acquired by gift giving, and potentially materialised an alliance between Roman authorities at Limes and a social group or leader from the region of Østfold, and as the burial custom broke so significantly with traditions, the performance of the burial had the potential to live on in the collective memory for a considerable span of time. Yet, the 600 years separating the construction of Stubhøj and Store Vikingegrav exceeds the average lifetime of oral history. That the specific content of a Roman period grave had lived on as part of the oral history of the place for such a long period is, in other words, possible but not obvious. Such an interpretational scheme would include a long continuity of people related to the place, and thus imply that the people living in this area and in this community had a relationship to the users of the place in the previous centuries.

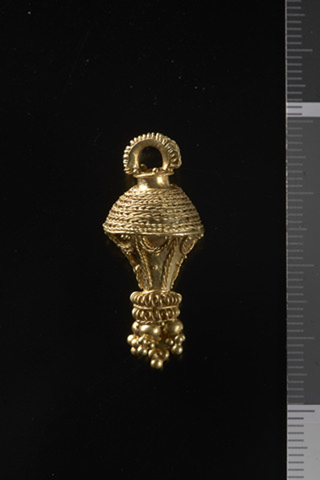

Thus, in the Viking Age, the very mound that is being referenced, imitated, or reinterpreted through the construction of Store Vikingegrav through the kerbstones, the location of the mounds in the cemetery and the grave goods and burial custom, is the one which contained the most prominent grave, constructed 600 years earlier. Several different scenarios can explain why people in the Viking Age could have understood these burial mounds as being particularly significant. In spite of the exterior resemblance between Stubhøj and Store Vikingegrav, the interior of the grave structure differed in one aspect. Stubhøj contained a grave cairn under the soil capping, as is typical for Roman period mounds in the region. The inhumation grave was located under three slabs placed under the cairn. In contrast, Store Vikingegrav was constructed of soil only (Resi Reference Resi1986, 63–85). Possibly the content in terms of grave goods was kept as part of oral history of the location, whereas the grave custom was not. An alternative scenario to oral history with deep time is that the in-depth knowledge was due to break-ins during the Viking Age in older graves. Break-ins or reopening of graves is a well-known phenomenon in Viking Age Scandinavia as well as in Early Medieval Europe, in pagan as well as in Christian contexts. The main purpose appears to be the acquisition of unique or rare artefacts (Aspöck Reference Aspöck2011; Bill & Daly Reference Bill and Daly2012; Capelle Reference Capelle, Jankuhn, Nehlsen and Roth1978; Klevnäs Reference Klevnäs2016; Klevnäs et al. Reference Klevnäs, Aspöck, Noterman, Van Haperen and Zintl2021; Lund Reference Lund2017; Myhre Reference Myhre, Hansen and Bjerva1994; van Haperen Reference van Haperen2010). In addition to break-ins of Viking Age graves during the Viking Age, a small selection of finds indicates that potentially older graves, and those specifically from the Roman period, were opened also. The Roman period gilded silver pendants with filigree work, so-called berlocks, are artefacts which typically occur in female graves in the Roman period, including in HunnFootnote 3 (Resi Reference Resi1986, 68–70). The berlocks appear in graves which are also equipped with Roman import artefacts (Lund Hansen Reference Lund Hansen1987). Such a berlock pendant from the Roman period has been found in a Viking Age grave in the cemetery at the trade site of Birka, Sweden (Arwill-Nordbladh Reference Arwill-Nordbladh, Pettersson and Skoglun2008). Berlocks have, however, also been reproduced in at least one instance. In the Viking Age female grave from Aska, Östergötland, Sweden, reproduction berlocks were among the grave goods, thus artefacts of a type and form that is otherwise exclusively found in the Roman period, 700 years earlier (Arwill-Nordbladh Reference Arwill-Nordbladh, Pettersson and Skoglun2008). Consequently, either this type of object was passed on as heirlooms through 25 generations, even though this artefact type does not appear in finds in the intervening 700 years; or, alternatively, the type was rediscovered by breaking into or reopening graves, a type of action not unusual in the Viking Age (see Lund Reference Lund2017 with references, for a discussion on the reopening of Viking Age graves). Though few in number, these finds indicate that some people in the Viking Age had intimate knowledge of the content of well-equipped Roman period graves of the type, which also included Roman imports.

One more Viking Age grave at Hunn had kerbing; the round mound F.44/A.L.46 was surrounded by relatively large, uniform kerbstones. The mound contained a cremation grave, including a number of undefinable iron objects, boat nails, burned human bones and fragments of a comb made of bone or antler, which can be dated typologically to the Early Viking Age (Resi Reference Resi1986, 81). It contained the cremated bone of one adult individual of indeterminable sex, and animal bones (Holck Reference Holck1997, 290). The mound was filled with sherds from at least two ceramic vessels, two fragments of flint and a clay lining, pointing towards the mound being constructed with soil from a cultural layer from a prehistoric settlement. Thus, in several ways, the grave created links to the past. Remains of Stone and Bronze Age settlements have been identified in Sydfeltet [the south field] of the Hunn cemetery (Resi Reference Resi, Chilidis, Lund and Prescott2008). The use of materials sourced from older graves or settlements to create the mound simultaneously connected Store Vikingegrav and F. 44/A.L. 46 to a much less specific past. These connections were physical and material. When a grave was constructed with the material from hundreds or thousands of years older remains of lived lives or of burials, time folded, while the references to the kerbstones surrounding the prominent Roman period mound created a direct connection to a specific past. This reuse of matter made the cultural layer endure (for a discussion on endurance, see Olsen Reference Olsen2010, 107–8), while simultaneously altering it. These cultural layers were never a specific structure with defined limits but were produced by a multitude of actions. When they are sourced as raw material for a mound in the Viking Age, they are transformed by these actions and made into new matter. Through their links to the past, the reality of the presence of ceramics was recognisable to the social groups that used them in the Viking Age, independently of whether the cultural layers were chosen as raw material or the use was purely accidental. These matters made a fold in time, where a distant past was brought into the contemporary.

The long continuity of the place must certainly have evoked a sense of deep time for anyone visiting Hunn during the Viking Age. Considering that the Viking Age mounds with kerbstones appear to be using the most conspicuous Roman period graves as a citational field, it raises the question of whether the constructors of the Viking Age mounds knew of the content of the Roman period graves, and of whether this knowledge was built upon. Either this information had been passed on orally, or it was obtained through the reopening of Roman period graves in the Viking Age. In other words, the capacities of the kerbstones are not merely defined by their materials as stones. A simplistic materialism approach would be to reduce them to just that: a bunch of stones. It is not their properties that are central here, but their capacities. Left only with oral history, the narratives of the burials would have little chance of surviving across centuries. The material qualities of the kerbstones on the Roman period graves made them endure. Further, they had capacities to trigger or construct memory. That the kerbstones are in use, fall out of use and are returned to and used in a later phase informs us that the kerbs work and are at certain points in time perhaps irrelevant and at other times clearly relevant. Even though today we can acknowledge the similarities between the interiors of the two graves, these similarities have not been directly accessible to the participants of the burial rituals of Store Vikingegrav through a visible connection, as they had never seen the burial rituals at Stubhøj. What they did have access to in the Viking Age was the exterior of the graves, and in addition potentially knowledge of the burial custom of the Roman period grave, either kept through oral history or gained through the reopening of graves. Thus, it was the tangible kerbstones, physically accessible for people in the Roman period, the Viking Age and even today, that created a connection across time.

Rather than reducing the reuse of the past to manipulative strategy of the elite, one may ask what role the past, or pasts, took during the Viking Age in this place. Independent of the motives for reuse, it clearly was part of the identities and self-perception of the social groups that conducted the burial actions. Considering that the specific, referenced mound of the Roman period included the material traces of long-distance relations in terms of alliances, this specific past and relation may still have mattered to people of the Viking Age. In addition, the grandeur of the Stubhøj mound in terms of its placement in the landscape and its sense of deep time made it relevant again in the Viking Age.

Store-Dal and Tune-Grålum

Similar scenarios to that at Hunn take place at two other cemeteries located in the area at the cemetery Store-Dal in Østfold, situated less than 2 km east of Hunn, and at the cemetery Tune-Grålum, 10 km north of Hunn. These sites have continuity from the pre-Roman Iron Age to the Viking Age. They each contain one Viking Age mound with kerbstones which appears to imitate a Roman period mound with Roman import and a gold berlock (Hougen Reference Hougen1924; P. Løken Reference Løken2002, 9, 33; T. Løken Reference Løken1974b, no. 248; Petersen Reference Petersen1916, 48–50) (Fig. 8). Mound 145 at Store-Dal was found north of a cairn (Petersen Reference Petersen1916, 25–6) and is in all likelihood a Viking Age secondary grave in a burial mound from the Roman or Migration Period. The find of flint in the mound soil further indicates that the mound was at least partly constructed with soil from an older activity layer, presumably from a Neolithic or Bronze Age settlement. This type of reuse of older cultural layers has also been identified in other Scandinavian sites (Artelius Reference Artelius2005; Artelius & Lindqvist Reference Artelius and Lindqvist2005; Fahlander Reference Fahlander2016; Hållans Stenholm Reference Hållans Stenholm, Andrén, Jennbert and Raudvere2006; Thäte Reference Thäte2007). Along with Stubhøj in Hunn, the imitated mound 6 from Store-Dal is the earliest known inhumation grave in Norway since the Bronze Age (Solberg Reference Solberg2003, 94). Similarly, the Viking Age inhumation grave no. 248 at Tune-Grålum with kerbstones may have imitated graves with Roman import at this cemetery (Løken Reference Løken2002, 9, 33) (Fig. 9).

Figure 8. The gold berlock from mound 6 at Store-Dal, eastern Norway (l = 3.3 cm.). (From Petersen Reference Petersen1916.)

Figure 9. Store-Dal cemetery. Star = Roman Period mounds with kerbstones; diamond = the Viking Age mound 145 with kerbstones. Mound 6 is the largest mound with kerbstones located to the southeast. Mound 5 is directly south of mound 6. (Map by Astrid Tvedte Kristoffersen and Julie Lund, based on Petersen Reference Petersen1916.)

The utility of mounds with kerbstones and construction materials also demonstrates a two-folded use of the past on these sites. The construction soil of the mounds is formed by the activity layer from Stone or Bronze Age settlements, whereas the very rare use of kerbstones links the Viking Age graves to the most prominent of the Roman period mounds. So, through the construction of the grave mound, a connection was made to a more specific past in terms of references to the Roman period mounds, while simultaneously using the materials of what must clearly have appeared to constructors as the remains of human activity from a less specific past.

Kerbing relations

Two diverging ways of using the past stand out in these examples: on the one hand the specificity of the past that is being imitated in terms of the references made to mounds with Roman imports; on the other hand, time is being folded through the use of profoundly older settlement sediments and other activity layers as part of mound building. The imitation of the Roman mounds demonstrates that reuse includes alteration. The mounds are typologically different in the interior, as the Viking Age mounds lack cairns. This reuse is referential, not material. The connection made to the distant and less distinct past by building the mounds from older cultural layers, on the other hand, is physical and material. In essence, through the imitations and references, and through the physical reuse features from the past, this produced a presence of the past in production. Furthermore, this reuse creates a link, a direct and physical connection, across time.

The past or pasts are being actively reused in many human activities for various reasons and purposes, consciously and unconsciously. Clearly, the past was also important to people in the Viking Age, as has been explored in numerous studies. There may be several very different reasons for this. We may never know what it meant or represented. Yet the sites from Østfold are examples of how specific pasts were emphasized and how different temporalities were consciously brought together. This specific exploration of the use of the past brings us closer to the variation in the ways in which the past could be used. It also indicates that not just any past was equally relevant here. By incorporating a less specific past in the mounds, the constructors of the mounds in the Viking Age created a connection to humans of a past that was otherwise lost to them. The simultaneous, specific reuse of the Roman past through the kerbstones shows that this relation was important. Rather than reducing this to a means of power, one may move the focus to their identity and self-perception and notice that this specific past was relevant for them, and thereby provide us with a closer insight into how these humans perceived themselves in this period.

The kerbs in Østfold used in the Viking Age were made up of locally collected stone. Building on the work of Karen Barad, Eloise Govier points out that matter plays a central part in the process of agential realism (Reference Govier2019, 53). However, what is at stake here is not the material qualities and properties of these stones, the substances in use, as they are simply local stones, presumably taken from the nearby scree. It is the ability of the kerbstones to work across time, or in other words, their capacities. The important matter is the relations which they create. Rather than simply underlining the effects of the materials—the stones in the kerb—what should be brought to the fore is the affects evoked using kerbstones. The kerbstones held potential energy as demarcations of the mounds through centuries. They marked what was inside and outside the mounds and the limitations of the grave monument. This energy is released kinetically as they are constructed as imitations in the Viking Age. Within the Viking Age, the kerbstones, older by 700 years, surrounding the Stubhøj structure affected humans and made them construct Store Vikinggrav with kerbs. Generally, in the Viking Age, the useful point of reference was the dominant Roman period mounds containing Roman imports. Thus, it is the particular affect caused by the kerbstones in this specific historical and contextual setting, not the general qualities of kerbs, which created the relations to the past. They were useful because kerbstones at this specific place had the capacity to simulate the very Roman mound in which the materiality of a particular set of social alliances was located.

We may ask how things come to endure (Fowler & Harris Reference Fowler and Harris2015, 127–9; Olsen Reference Olsen2010, 158–9)? What gave the kerbstones this resilience? Or, in other words, what made them relevant for the Viking Age? And as Siân Jones and Lynette Russell ask, how do authoritative narratives emerge and persist (Jones & Russell Reference Jones and Russell2012, 268)? Obviously, their mere physical qualities and properties played a part, as their durability as stone gave them the ability to endure. Furthermore, their properties as markers of boundaries between the mound and the surroundings may have worked through time, independent of the cultural context, as a fundamental feature for the bodies of humans and the bodies of objects (for a discussion on general features and qualities by which the human body relates to the world, see Lakoff & Johnson [1980] Reference Lakoff and Johnson2003). Yet it was not simply the properties of the kerbstones which gave them such persistent effects. Rather, it was their capacities to affect. Though seemingly insignificant, the kerbs which made the Viking Age mound blend in on these cemeteries with extremely long continuity, were also what differentiated these three from the other 267 graves, including those in other, contemporary mounds in the region which did not have kerbs. These changes happened with varying speeds and rhythms (see Crellin Reference Crellin2017). Thus, by focusing on the capacities of the reused material culture, and on the affects of it, a more nuanced perspective on Viking Age reuse potentially appears, in which the meeting points between different times are emphasized. This reuse indicates that the reused past was not picked randomly, but was chosen due to its capacity to connect human beings in the Viking Age with a particular set of social relations that would otherwise have ended 700 years earlier. Instead of searching for a one-size-fits-all explanation of reuse, a fruitful avenue to pursue may be to show more sensitivity towards the diversity within reuse, and thus explore how reuse unfolds and is expressed within this spatial and temporal setting. A perspective on reuse which focuses on capacities and affects aims at giving an insight into aspects of identities and self-perceptions, as it was specifically the Roman period graves which contained the material remains of long-distance contexts that were reused and referenced. The kerbs on the older mounds had affected people using the cemetery over time through centuries. The creation of the kerbs surrounding the Viking Age mounds at Hunn, Store-Dal, and potentially Tune-Grålum, gave them the ancient appearance of a Roman period mound, and thus had the potential to evoke a sense of being old, and of time depths. In the Viking Age, these cemeteries had already been in use for more than 1000 years. Thus, by creating a link to the past, they could also evoke a sense of belonging. As pointed out by scholars working with Anglo-Saxon England, the use of the past was in this period deeply linked to aspects of self-perception, identity, and of integration of the past landscape in new conceptualizations of the world (Semple Reference Semple2013). These notions resonate well with the use of the cemeteries in Østfold. When the relational affectivity is treated analytically, we may get a better grip on decision making and a better understanding of who and what is influencing whom and what. We may, in other words, nuance our understanding of decision making and thus also of the construction of power relations in the Viking Age. Using the kerbstones constituted collective actions which were part of an interplay between actors, matters and location in the landscape across time. Through the sense of age and attachment to the Roman period structures, Store Vikingegrav may have become ‘sticky with emotions’, as Oliver Harris has put it, and thereby made into a memorable place (Harris Reference Harris2009). As part of the self-perception of Viking Age Hunn, the specific past of the Roman Iron Age with Roman connections was a relevant point of reference for copying and imitation. Simultaneously, a much less defined past was reused and thereby altered through the construction of the mounds. Consequently, very different types of social relations and various relationships between time and memory were produced, maintained and expressed in the cemetery. Time thus moved within linear and non-linear dynamics, of which some turned out to be long lasting, as the kerbstones are still present at the mounds in Hunn in situ, where the mound within the kerbstones has been reconstructed from the soils of the excavated areas.

Acknowledgements

This paper was written as part of the project ‘Using the Past in the Past. Viking Age Scandinavia’ funded by the Research Council of Norway (project no. 250590). An earlier draft of this paper was presented at the session Capacious Archaeologies at the TAG 2019 conference in London. I wish to thank the organisers of the session, Ing-Marie Back Danielsson, Andrew M. Jones and Ben Jervis, and the participants for fruitful discussions. Further, I wish to thank Chris Fowler, Mette Løvschal and John Ljungkvist for their comments on an earlier draft of this paper at the workshop Time and Temporality in the Viking Age, and Martin Furholt and Rebecca J.S. Cannell for comments on and inputs to the paper. Finally, I wish to thank the two peer reviewers and the editor for their useful comments.