Introduction

As Park et al. (Reference Park, Littleton, Chambers and Chambers2011, 8; Hountondji Reference Hountondji and Hoppers2002) argue, it is high time we stopped reducing ‘what might be construed as indigenous social theory to data, rather than recognising it as theory’. It is time to ‘put indigenous knowledges to work’ rather than just treating them with ‘exquisite politeness’ (Gillett Reference Gillett2009, 11; Park et al. Reference Park, Littleton, Chambers and Chambers2011, 8). Indigenous voices speak to similar frustrations. The Te Hau Mihi Ata research project in New Zealand, for example, was set up ‘to negotiate spaces for and develop processes of dialogue that allow for a deeper level of interaction between matauranga Maori (Maori indigenous knowledge) and science’. ‘The genesis of the project was motivated by community concerns at the framing of matauranga Maori (indigenous knowledge) as only relevant in a traditional context’. In response, the project sought to ‘unlock’ the innovation potential of Maori knowledge, people and resources’ (Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Roberts, Smith, Tiakiwai and Hemi2012, 11–12) by considering how it might inform new biotechnologies in unanticipated ways.

My aim in this paper is more modest. First I introduce the Maori theory of whakapapa; what it is, how it is understood; how it is employed by Maori and by non-Maori academics in New Zealand. My hope is this brief overview of current thinking around ideas of whakapapa as social and scientific theory may inspire a wider community to examine these ideas more closely and consider employing them in innovative ways. To conclude, I point briefly to how whakapapa might be ‘unlocked’ or ‘put to work’, as archaeological theory.

Whakapapa is loosely, and reductively, translatable as genealogy or ancestry, but includes connotations of layering, and to lay flat (Lander Reference Lander2017; Ngata Reference Apirana2019; J. Roberts Reference Roberts2006; Salmond Reference Salmond2019). Like other indigenous theories recently favoured by archaeologists, whakapapa is ‘inherently values based’ (Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Roberts, Smith, Tiakiwai and Hemi2012, 12). It constitutes a moral and ethical framework for living founded in what western theory would describe as a posthuman world—namely, a world which does not acknowledge any fundamental division between humans, other living forms and the material, spiritual and social environments in which all live (M. Roberts Reference Roberts and Keenan2012; M. Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Haami, Benton, Scatterfield, Finucane, Henare and Henare2004, 4). Whakapapa is both theory and practice; it is a way of thinking, being and acting. M. Roberts (Reference Roberts2010, 1) describes it as a ‘mind-map’, ‘a genealogical framework upon which spiritual, spatial, temporal and biophysical information about a particular place is located’.

While whakapapa has much in common with western ideas of genealogy and evolutionary theory, there are fundamental differences (Gillett Reference Gillett2009; Salmond Reference Salmond2019). As Hudson et al. (Reference Hudson, Roberts, Smith, Tiakiwai and Hemi2012, 13) argue with respect to scientific knowledge, critical ‘differences lie in the way knowledge is assembled and in the ways in which people, practices and places become connected and form knowledge spaces’. These differences are powerful, and the difficulties which arise when seeking to develop ‘a creative interface between different knowledge systems’ should not be underestimated. However, with time, positive engagement, acknowledgement and respect, a ‘negotiated space’ can be opened (Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Roberts, Smith, Tiakiwai and Hemi2012, 14).

Indigenous voice

Archaeologists are increasingly employing indigenous theories to interpret archaeological materials. Among the attractions of indigenous theories is their foundation in fundamentally ‘otherwise’ posthuman ethical and moral worlds (cf. Alberti et al. Reference Alberti, Fowles, Holbraad, Marshall and Witmore2011). Unsurprisingly a common subject for interpretation is forms of ‘artwork’. Whether ancient, modern or contemporary, art is a forum through which people seek to explore and express something of the profundities of life and living—art takes the shape of a material enquiry into the world. Shamanism, for example, has been highly influential in the interpretation of southern African rock art (Dowson Reference Dowson1998; Tomášková Reference Tomášková2013). More recently, perspectivism (Viveiros de Castro Reference Viveiros de Castro1998; Reference Viveiros de Castro2004) and animism (Willerslev Reference Willerslev2007) have attracted considerable interest.

Unfortunately, academic use of these indigenous theories is fundamentally dependent on an anthropological interpreter, commonly a single authoritative voice, to make them accessible to other academics, including archaeologists. Indigenous voices come to us in academic anthropological writing, rather than speaking directly for themselves. Many archaeologists find this situation unsatisfactory and indigenous voices are increasingly heard directly in published archaeological writing (e.g. Nicholas Reference Nicholas2010). In addition, archaeologists have actively sought insight in published indigenous writing, such as the work of Vine Deloria (Reference Deloria2003).

Whakapapa is a social theory with a strong, accessible indigenous voice. A special issue of The Journal of the Polynesian Society, focused on whakapapa, has highlighted the influential work of Maori scholars during the early twentieth-century development of anthropology in New Zealand (Lythberg & McCarthy Reference Lythberg and McCarthy2019). As part of this work, the national Board of Maori Ethnological Research, Te Poari Whakapapa, established by Apirana Ngata, identified anthropology as a key vehicle for promoting Maori self-identified development (McCarthy & Tapsell Reference McCarthy and Tapsell2019; Ngata Reference Apirana2019). Numerous Maori-authored publications have subsequently described and interpreted whakapapa for both Maori and non-Maori audiences (Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Ahuriri-Driscoll, Lea and Lea2007; Mahuika Reference Mahuika2019; J. Roberts Reference Roberts2006; M. Roberts Reference Roberts2010; Reference Roberts and Keenan2012; Reference Roberts2013). For those who wish to find it, Maori scholarship on whakapapa is accessible in published forums and need not be read through an anthropological interpreter.

Beyond academic writing, whakapapa remains fundamental to both everyday and ceremonial Maori life. Some contexts for the practice of whakapapa are socially restricted, such as formal or ceremonial events on marae where speeches based in whakapapa are delivered by authoritative cultural experts. But whakapapa also resides in museums, in cultural centres, and is lived everywhere, every day, even in the use of humble objects (Maihi & Lander Reference Maihi and Lander2008). It can be encountered and experienced by any visitor to New Zealand who chooses to take an interest.

What is whakapapa?

Western genealogies are presented as a formal ordering of persons arranged as a branching tree. There is presumed to be a ‘correct’ structure (cf. Ingold Reference Ingold2007; Reference Ingold2011). In contrast, whakapapa are dynamic and relational, ‘a cosmological system for reckoning degree of similarity and difference, determining appropriate behaviour, and manipulating existing and potential relationships to achieve desired effects’ (Henare Reference Henare, Henare, Holbraad and Wastell2007, 57). Whakapapa are not essentialist schemas that determine who a person is, or who is/is not a member of a specific group. Whakapapa do not fix identities; they frame possibilities. They set out differences and commonalities in a contingent, positioned frame rather than in categorical terms. A whakapapa always speaks to the requirements and desired outcomes of the particular persons, context and situation in which it is presented—it is always contextual, situated and purposeful.

A key metaphor for whakapapa is the gourd plant or hue, Cucurbita lagenaria vulgaris (Neich Reference Neich1993, 39), never a tree (Ngata Reference Apirana2019, 26). In contrast to the metaphor of a fixed, rigidly upright, branching tree, a gourd plant takes its shape and direction from the context or environment in which it grows. It is a vine which scrambles along the ground, up and over whatever it encounters. Whakapapa is situated knowledge (cf. Haraway Reference Haraway1991). A whakapapa speaks from a specific geographically, socially, even mythically embodied place. In addition, it speaks purposefully. Although its direction is open and contingent, it is always responding to a stated problem, question or purpose. A whakapapa can never become generalized truth; it is always specific and explicitly purposeful and therefore also ethically and morally engaged.

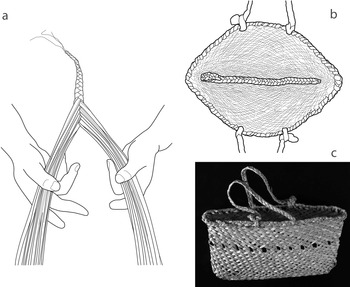

Whakapapa is materialized in many, if not all, Maori art forms. Most spectacular of these is the decoration on and in a whare whakairo, a large decorated meeting-house which forms part of the marae complex where events are held to mark life-crisis celebrations and hold important meetings. Formal speeches based in whakapapa take place both inside and on the open ground directly in front of the house. The wood carvings, woven tukutuku boards and painted kowhaiwhai rafter designs which adorn the house all speak in whakapapa, each in their own way. Kowhaiwhai designs, for example, take the form of trailing gourd plants (Neich Reference Neich1993; Reference Neich2001), and were once common on canoe paddles and gourd containers (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Kowhaiwhai designs based on the growing habit of the gourd plant or hue (left). Early nineteenth-century incised gourd container. The background fill of the design has been simplified to highlight the formline or manawa lines. Length 32 cm. (Collection of the British Museum. Starzecka et al. Reference Starzecka, Neich and Pendergrast2010, 42, no. 187.) (A) Early nineteenth-century painted canoe paddle or hoe. Complete length including handle (not shown) 202.5 cm. (Auckland Museum, 22068.3. Neich Reference Neich1993, 68.) (B) Late eighteenth-century painted canoe paddle or hoe. Complete length including handle (not shown) 180 cm. (Cambridge University Museum, Cook collection; Neich Reference Neich1993, 64.) (Drawings: Penny Copeland.)

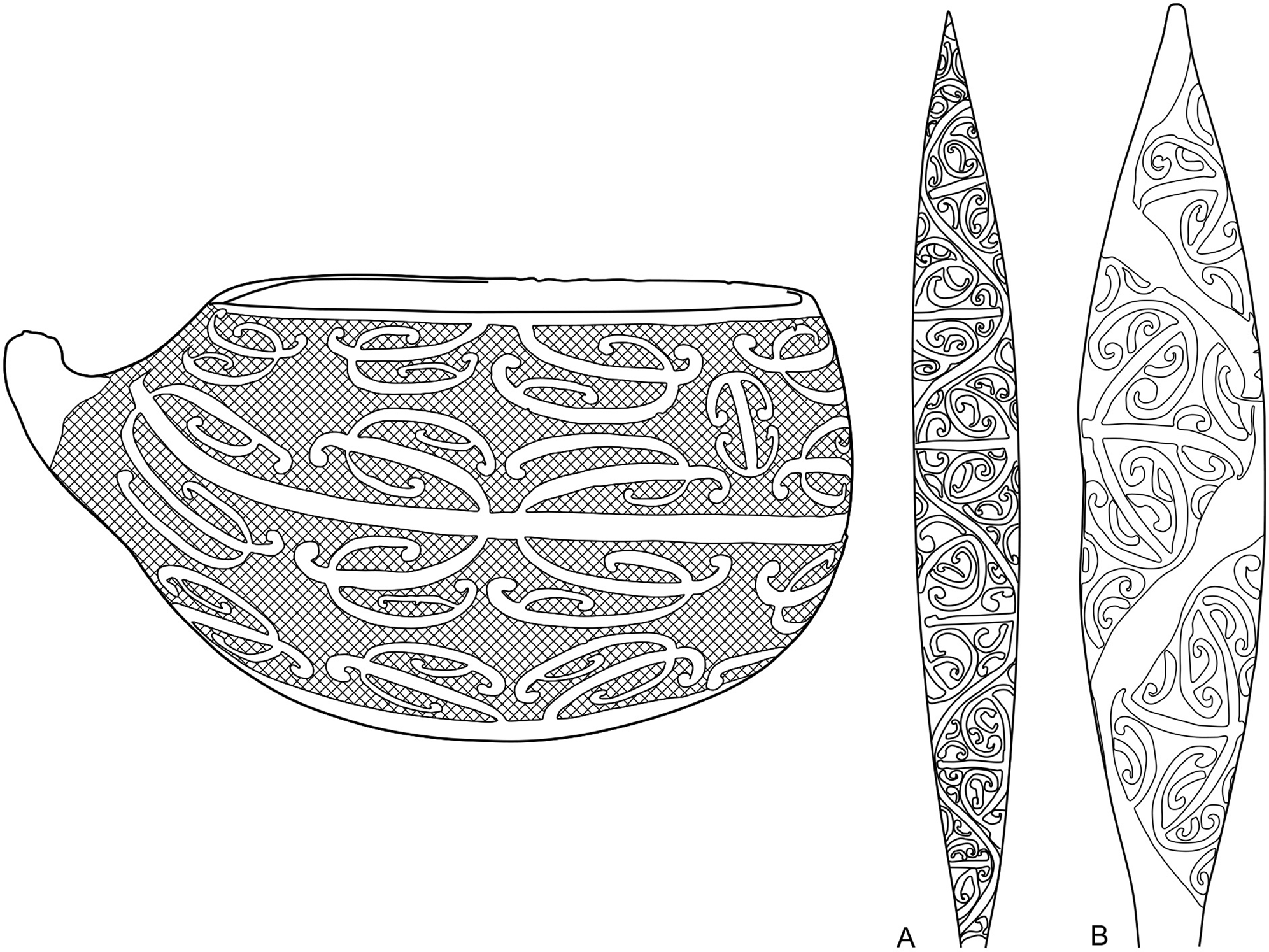

But whakapapa is also everyday practice. Take, for example, the woven flax basket, the kete, possibly the most ubiquitous and versatile item of all Maori material culture. Most people in New Zealand have one and most Maori have several. They are used for anything and everything; as planters, to carry laundry, a purse for formal social occasions and more metaphorically as ‘baskets of knowledge’ (Maihi & Lander Reference Maihi and Lander2008). They may even be employed to carry dreams (Maihi & Lander Reference Maihi and Lander2008, 70). Thus the social lives of kete are entwined with those who use them; ‘every kete has a story’ (Maihi & Lander Reference Maihi and Lander2008).

Construction of a kete follows a parallel path to the narration of a whakapapa. It begins with a foundation plait, as shown in Figure 2a, drawn from a 1921 photograph by James McDonald (Salmond & Lythberg Reference Salmond and Lythberg2019). The initial threads are fine and thin but build substance as additional strips of prepared flax, harakeke (Phormium tenax), are progressively worked in. The long, unplaited flax ends are then used to weave the body of the kete, in the process encasing the foundation braid inside the kete to form its base (Fig. 2b). When finished, the foundation braid lies hidden inside (Fig. 2c), unless the kete is opened out for use.

Figure 2. Weaving a flax kete. (a) Beginning a foundational braid or whiri from which the weaving of a kete will be grown. (Drawn from a 1921 Alexander Turnbull Library photograph PA1-q-257-42-5. Paama-Pengelly Reference Paama-Pengelly2010, 43.) (b) The completed foundation braid runs along the inside, forming the base of a finished kete. (Drawing: Penny Copeland.) (c) In a completed kete the braid is hidden from outside view. (Photograph: Andrew Crosby, author's collection.)

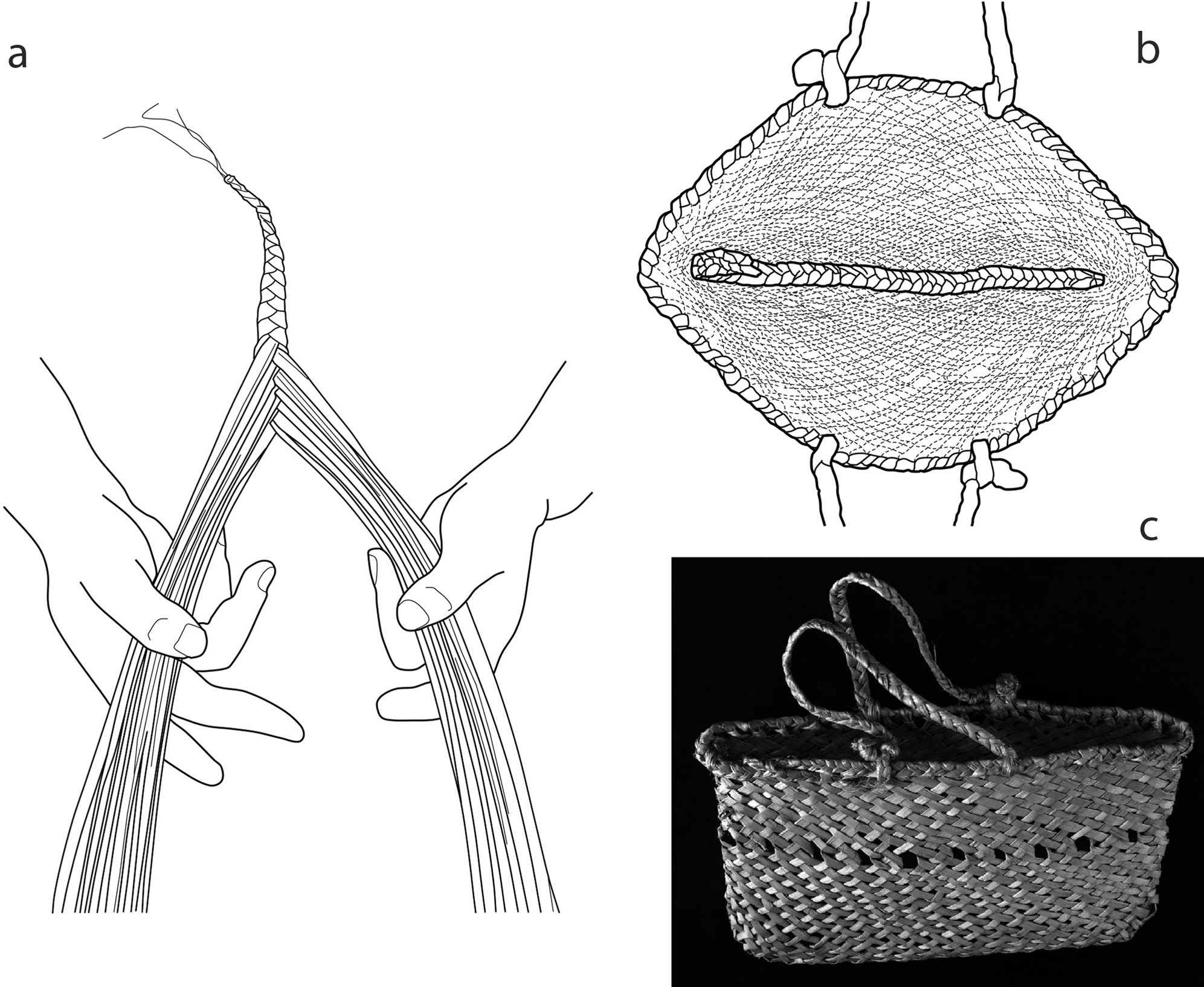

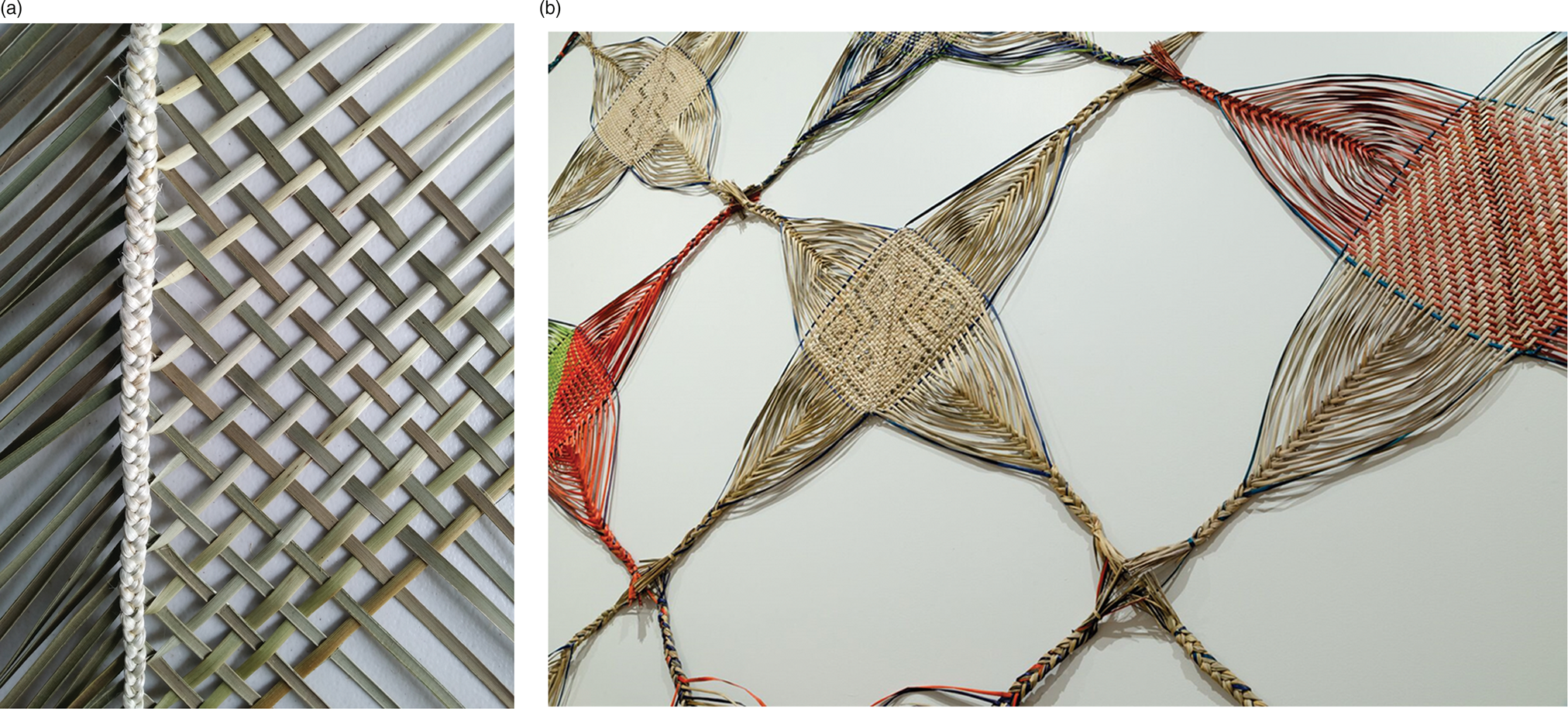

In her most recent installation, Flat Pack Whakapapa, multi-media artist Maureen Lander explores this connection between kete, whakapapa and weaving, linking it also to genetics (Lander Reference Lander2017). Her work was displayed in the exhibition space at the Dowse Art Museum in 2017 and is currently touring other venues across New Zealand (Mata Aho Collective 2017; Dowse 2017; Lander Reference Lander2017). The installation is composed of three parts; diy-DNA, Flat-Pack Whakapapa and Kit-Set Whanaungatanga (Fig. 3). Each part plays provocatively with the idea that because whakapapa is ‘always with us’ it can be ‘packed down’, ‘carried around, reconfigured and added onto later’; ‘whakapapa grows with us’ (Dowse 2017).

Figure 3. Three components of Maureen Lander's installation Flat-Pack Whakapapa, as displayed in the Dowse Art Museum Exhibition Space, 2018. On the rear wall: diy-DNA, 2017, haraheke, muka. (Collection of the Dowse Art Museum, purchased 2017.) In the right foreground: Flat-Pack Whakapapa, 2017, harakeke, muka. (Collection of the artist.) Along the left side wall: Kit-Set Whanaungatanga, 2017, harakeke, Teri dyes. (Collection of the artist and her weaving collaborators.) (Photograph: Mark Tantrum.)

In Figure 3, diy-DNA is positioned along the rear wall. It consists of huge DNA strands made from rolled flax leaves with braided muka [flax fibre] which visitors can walk amongst. It is a gentle provocation to question and challenge new biotechnologies such as Ancestry DNA websites and gene manipulation processes. It is also explorative; ‘diy-DNA opens a space to consider why similar narratives unfold within different cultures and religions, and how mythology, science and technology have all been used to try to understand where we come from, and what makes us who we are’ (Dowse 2017).

On the wall to the right is Flat-Pack Whakapapa. It draws on two core meanings of whakapapa: to line up, as in genealogy, and to lie flat or place in layers. A continuous line of opened (flat-packed) kete extends vertically up the wall and down into a horizontal pile. Each kete is joined to its neighbours by the ends of its four finishing braids (see Figure 4). The four vertical kete are ancestors, who came before us but ‘guide us into the future’; the top horizontal kete is the present, and our descendants follow into the pile beneath. Every kete, every person, is both unique in themselves and composed by connections to multiple others (Dowse 2017).

Figure 4. (Left) The foundation braid and initial weaving for a section of Flat-pack Whakapapa. Maureen Lander, Whiri Commencement (Whakapapa) for Flat-Pack Whakapapa (work in progress) 2017. (Photograph: courtesy of the artist.) (Right) Detail of several whakapapa sections of Kit-Set Whanaungatanga. Note how each section is grown from four foundation braids or whiri, which also join each section to its neighbours. (Photograph: Shaun Matthews.)

This theme of composition in others continues in the largest part of the installation located on the left wall, Kit-Set Whanaungatanga. It is a collaborative work by Maureen and a group of weavers called her A-team—her awhina team, meaning to help and befriend. Kit-set Whaunangatanga is about family (whanau) and our social networks of kin, friends, colleagues and others. As in Flat-Pack Whakapapa, each person is a kete woven from a single foundation braid (whakapapa) and completed with four finishing braids which reach out and join directly to four more, and on from them to all others (Figs 3 & 4). All members of the A-team wove several kete, ‘each with a predetermined set of criteria that included technique, size, colour and pattern. Even so, as in the narrating of whakapapa, every weaver had some freedom to express their skills, creativity and individuality’ (Dowse 2017).

Flat-Pack Whakapapa visually and conceptually sets out the fundamental principles of whakapapa while also asking us to question, challenge and critique claims which potentially erode its open, situated way of knowing—claims which run counter to its ethical and moral foundations. It is these characteristics of whakapapa which make it powerful in Maori lives, and potentially also as academic theory.

Applying whakapapa in New Zealand scholarship

For many years, Mere Roberts has championed whakapapa as scientific and social theory. It is largely through her work that the application of whakapapa has moved beyond Maori scholarship and practice into scientific research (M. Roberts Reference Roberts2010; Reference Roberts and Keenan2012; Reference Roberts2013; M. Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Haami, Benton, Scatterfield, Finucane, Henare and Henare2004). Roberts trained as a biologist, initially in zoology, but her work is fundamentally interdisciplinary, cross-cultural and collaborative. She has held academic positions in biology, medicine, environmental science and anthropology, publishing widely across these fields. In its open engagement across the layered worlds of academic disciplinary practices, and across Maori and science-based ontologies, her career exemplifies whakapapa in practice.

Roberts’ whakapapa of natural and material worlds have been especially influential. Using the whakapapa of kumara or sweet potato, Ipomea batatas, as her starting-point, she draws out how ‘Maori knowledge concerning the origin and relationships of material things like the kumara is visualised as a series of co-ordinates arranged upon a collapsed time-space genealogical framework’ (M. Roberts Reference Roberts and Keenan2012, 40). There are fascinating resonances here with the work of geographer Doreen Massey (Reference Massey2005). A key principle is ‘ascribing origins and the “coming into being” (or ontology) of each known thing’ (M. Roberts Reference Roberts and Keenan2012, 41), a relational process which may draw in varying combinations of plants and animals, and ‘permits the inclusion of non-biological phenomena’ such as celestial bodies, while also precluding any possibility of a nature/culture divide (M. Roberts Reference Roberts and Keenan2012, 40–41).

Stepping off from Roberts work, whakapapa has been employed to evaluate emerging new biotechnologies such as GMO Generically Modified Organisms (Gillett Reference Gillett2009; Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Roberts, Smith, Tiakiwai and Hemi2012; M. Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Haami, Benton, Scatterfield, Finucane, Henare and Henare2004). The relational character of whakapapa makes it especially well-suited to studies which evaluate combinations of factors, for example the intertwining of genetic and environmental factors which underlie distinctive patterns of disease and ill-health in Maori communities (Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Ahuriri-Driscoll, Lea and Lea2007). Park et al. (Reference Park, Littleton, Chambers and Chambers2011) chose a whakapapa approach to examine the spread and impact of tuberculosis in Pacific populations. Tuberculosis is well known to have social as well as biological and environmental risk factors, and in their study Park et al. highlight among other influences the critical impact of immigration policies, calling into question the ethical and moral principles embodied in these policies.

Two features of this emerging body of work stand out. First, it is fundamentally located in debates concerning the moral and ethical contexts of research. Hudson et al. (Reference Hudson, Ahuriri-Driscoll, Lea and Lea2007, 45) speak in particular of ‘dual accountability’, the requirement both to be accountable to the interests of Maori kin and community and to enforce rigorous academic research practice. While often uncomfortable, these dual pressures do have the power to enrich and enhance standards of research practice (cf. O'Regan Reference O'Regan and Nicholas2010; Rika-Heke Reference Rika-Heke and George2010). Secondly, the majority of work engaging with whakapapa has been directed towards the development of culturally informed social policies, rather than seeking solutions to scientifically defined research questions. This is in part because reframing the moral and ethical context of research through whakapapa inevitability challenges the appropriateness and applicability of the questions being asked. In other words, it not necessarily the case that Maori theory such whakapapa cannot inform research solutions, but rather that we have been asking scientific questions of little relevance to Maori. A broadening of research objectives might draw in Maori scholars and enrich scholarly debate more generally.

Applying whakapapa in archaeology—an international reach?

The qualities of whakapapa which I have chosen to highlight are its moral and ethical embeddedness and its insistence on contextually informed, multiple forms of relating. These qualities have strong resonances with other open-ended methodologies and posthumanist theories employed by archaeologists, particularly feminist writers such as Karen Barad, Elizabeth Grosz and Donna Haraway (see Alberti & Marshall Reference Alberti and Marshall2009; Marshall Reference Marshall2000; Reference Marshall2008; Marshall & Alberti Reference Marshall and Alberti2014). They also resonate closely with Joan Gero's call to value, even highlight, the ambiguities inherent in all archaeological data (Gero Reference Gero2007; Reference Gero2015).

In recent work, I have employed whakapapa as archaeological method and theory for the analysis of Maori whalebone pendants—objects which are considered artworks (Lyons & Marshall Reference Lyons and Marshall2014; Marshall Reference Marshall and Thomas2020; Marshall & Alberti Reference Marshall and Alberti2014). With the exception of one small fragment, none of these objects have secure archaeological provenance, so although they are exceptional in many ways, they are difficult to interpret and little has been written about them. My purpose was to use a whakapapa approach to open up our thinking about these objects to new possibilities. By drawing on a wider range of data, including the work of contemporary bone carver Brian Flintoff (Reference Flintoff2011), I sought to develop a broader understanding of their meaning and significance in Maori lives past and present. Whakapapa was a particularly appropriate analytical choice for these objects, because in themselves they embody whakapapa. Their design and narrative materializes both a specific telling of whakapapa and the principles on which whakapapa is founded.

My application of whakapapa stayed close to its Maori and New Zealand origins, and it follows the well-trodden path in archaeology of employing indigenous theory to explore art objects. However, whakapapa has the potential for greater reach, beyond New Zealand and beyond archaeological art objects.

Given the forums in which whakapapa has already entered academic debate in New Zealand, an obvious area of international research where it could make a contribution is the application of genetics in archaeological studies. This new and fast-moving field is symptomatic of two features of contemporary archaeological research: the extraordinarily large bodies of data which can now be produced, sometimes very simply and cheaply, and the extraordinarily rich array of interdisciplinary forms of data potentially available to address any archaeological question. Employing these vast, diverse databases effectively and appropriately presents stiff challenges. An object lesson in just how challenging this might prove is the development of radiocarbon dating. There has been a very long road through initial simplistic assumptions, confusions and contradictions, repeated programmes of radiocarbon hygiene, to reach radiocarbon enlightenment and confidence. A similar path is envisaged for the application of contemporary and ancient DNA research in archaeology. Limitations in western evolutionary theories encourage simplistic, reductionist interpretations (see Ingold Reference Ingold2007; Reference Ingold2011; SAA 2019, for critiques). Lessons in building cross-cultural approaches to scientific practice, already being addressed in New Zealand as whakapapa becomes more widely employed, could inspire new modes of analysis and lead to more insightful outcomes.

For example, we might try weaving insights from Mere Roberts’ whakapapa of kumara, sweet potato, with analysis of the genetics of modern Pacific sweet potato varieties and ancient DNA analyses of the small selection of archaeological specimens recovered in the Pacific. The aim would be a uniquely interdisciplinary, cross-cultural whakapapa of Pacific sweet potatoes. The foundation braid for such an analysis might focus on the homeland of sweet potato, South America. On the other hand, given the diversity of conventional and novel data available, a new form of foundation and weaving technique might be needed. When Toi Te Rito Maihi began weaving kete from seaweed in 1992, she quickly learnt that, due to the brittle nature of the drying seaweed, a conventional foundation braid and weaving technique could not work. A specific weaving technique tailored to each type of seaweed or kelp was in fact required (Maihi & Lander Reference Maihi and Lander2008, 72–4). To employ whakapapa as scientific and social theory will similarly require improvization and innovation.

A case in point is how to interpret the past of Pacific people. Conventional archaeological accounts of Pacific prehistory have generally sought to distil out master narratives from multiple strands of evidence. For example, Kirch and Green (Reference Kirch and Green2001) employed a process they described as triangulation. Evidence from three disciplines, linguistics, ethnology and archaeology, was triangulated to identify points of convergence and produce a distilled essence for interpretation of past events. Many more forms of evidence have since become available. Especially prolific are data arising from genetic analyses of people, plants and animals. Fortunately, however, whakapapa works in the opposite way to triangulation. Rather than distilling down, whakapapa opens up the evidence base, drawing in and weaving together multiple strands of diverse data, while also seeking to maintain the disciplinary integrity of each strand. It is an approach well suited to our surprising new condition of overwhelming riches of data.

Conclusion

Whakapapa is well-established in New Zealand as both theory and practice. It is fundamental to Maori society, past and present, and it has emerged as a powerful forum for the development of social policy in a range of contexts. It is also increasingly employed to inform academic research across a variety of disciplines. My primary purpose in this paper has been to bring this work on whakapapa to the attention of an international audience. With this in mind, I have highlighted those features of whakapapa which have already demonstrated power to inform interdisciplinary and cross-cultural research, and to challenge our research cultures. Above all, whakapapa is purposeful, engaged research. It demands work where something is actually at stake for all participants and subjects. Such work produces both novel insights and morally and ethically enriching outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This paper would never have been written without the encouragement and advice of Maureen Lander, Toi Re Rito Maihi and Julie Park. Many thanks to Maureen Lander, and to The Dowse Art Museum for permission to use images from Flat-Pack Whakapapa. Thank you to Penny Copeland for her beautiful figure drawings.