Introduction

American business organizations powerfully shape the trajectory of the American political economy.Footnote 1 It matters how business organizations respond to societal issues and social movements. This article aims to advance our understanding of American business organizations’ responses to Black Lives Matter (BLM), with a particular focus on the US Chamber of Commerce, the “most powerful business lobby in American history,”Footnote 2 as well as state-level and regional chambers of commerce.

The #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) movement was established when George Zimmerman was acquitted for shooting Trayvon Martin. Following the killings of Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Sandra Bland, Freddie Gray, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Jacob Blake, and many other Black and Brown people, this movement has grown, culminating in unprecedented protests following the brutal murder of George Floyd.

My examination of American business responses to BLM begins with the US Chamber of Commerce, the world's largest national business federation. Since the 1970s, the US Chamber has engaged in aggressive interest group advocacy or “organized combat,”Footnote 3 with far-reaching consequences for the American economy and society. In recent years, the US Chamber has spent more than a billion dollars on lobbying and campaign contributions.Footnote 4

As the world's lobbying capital, Washington, D.C., is of course “a world unto itself with its own motivations and self-interest.”Footnote 5 To shed light on developments in local communities, this article also includes the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) activities of state and regional chambers, which have developed in parallel with, and with varying degrees of input and coordination from the US Chamber. The ways in which business organizations across the United States respond to racism and BLM has important consequences for the American economy and society: “[G]iven the clout of the American business community, any sign that executives are reorienting their political practices to address the nation's growing political and social dysfunction is welcome.”Footnote 6

This raises the questions: How have the US Chamber and chambers across the United States responded to BLM and the challenges of DEI, the toolkit and language that the business community uses to signal that it is responsive to concerns about racial inequality, including some of those raised by the BLM movement?Footnote 7 To what extent have business stances and actions changed? Because the literature on American business responses to BLM is in its infancy, this article builds on fieldwork, careful observation,Footnote 8 and archival research to delineate this “fundamentally novel empirical terrain,”Footnote 9 advance an argument, and set an agenda for future work on the relationship between BLM and business organizations.

This research matters because of the role that business can play in helping to overcome racial inequities and racial resentment:

Businesses and business leaders are uniquely suited to help aid in what King called the struggle for genuine equality, because they control so many critical financial and economic levers. Through thoughtful corporate social activism, particularly when it complements public policy reforms, activists and capitalists can help undo some of the lasting legacies of America's original sin on matters of race.Footnote 10

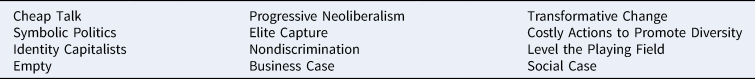

The extent to which business organizations and individual businesses contribute to these goals will depend on their stances and actions. It is safe to assume that a substantial number of chambers and businesses continue with business as usual. These cases of nonresponse are not the focus of this article. For chambers that do respond to BLM I offer the following typology of stances and actions in Table 1.

Table 1. Stances and actions, from empty and weak to radical and transformative

Cheap talk, symbolic politics, and identity capitalists have one thing in common: a focus on words, show, and talk rather than on costly and meaningful action. In this vein, Leong points to the problem of “identity capitalists”: “those who do nothing of substance but showcase their superficial affiliation with members of racial outgroups.”Footnote 11 The claim here is not that rhetorical commitments in support of DEI or BLM by representative bodies such as chambers are unimportant and inconsequential, but that they are problematic if they are used as a deliberate low-cost strategy to substitute for meaningful action.

Progressive neoliberalism, elite capture, and nondiscrimination contain elements of symbolic politics,Footnote 12 but their overall emphasis is somewhat different: When confronted with social pressure and critiques from activists, elites and progressive neoliberals focus on words and action to advance diversity, while steering developments in a market-conforming direction. In this vein, radical authors disparagingly refer to “neoliberal democrats and the capitalist blocs they serve.”Footnote 13 Following Fraser, we can distinguish between Donald Trump's reactionary populism, progressive neoliberalism, and progressive populism. In Fraser's words, “The progressive neoliberal program for a just status order did not aim to abolish social hierarchy but to ‘diversify’ it, ‘empowering’ ‘talented’ women, people of color, and sexual minorities to rise to the ‘top.’”Footnote 14 In the elite capture view,Footnote 15 elites co-opt identity politics to pursue corporate DEI goals, which allows them to emasculate movements such as BLM and pursue goals that are not in lockstep with the constituencies they ostensibly represent.

Roemer's conceptions of equality of opportunity are relevant here. According to his nondiscrimination principle,

In the competition for positions in society, all individuals who possess the attributes relevant for the performance of the duties of the position in question [should] be included in the pool of eligible candidates, and … an individual's possible occupancy of the position be judged only with respect to those relevant attributes.Footnote 16

Despite the popular legitimacy of the nondiscrimination principle, the racism that gave rise to BLM shows that we have a long way to go. By affirming their support for the nondiscrimination principle, business organizations can make a valuable contribution, even if more radical and critical voices view this as garden variety progressive neoliberalism.

The third category encompasses bolder and more transformative actions that chambers can undertake. Roemer's first conception of equality of opportunity is relevant here, according to which:

society should do what it can to “level the playing field” among individuals who compete for positions, or, more generally, that it level the playing field among individuals during their periods of formation, so that all those with relevant potential will eventually be admissible to pools of candidates competing for positions.Footnote 17

As Roemer points out, the level-the-playing-field principle “goes farther than the nondiscrimination principle”—it may require an equalization of educational expendituresFootnote 18 or other costly investments. Bold, transformative, and costly actions are undertaken by actors with a sincere commitment to principles that goes beyond narrow self-interest. If chambers do try to level the playing field by diversifying their own membership or changing the legal framework to advance the cause of racial equity, this can have far-reaching effects because chambers are politically potent and well-resourced organizations. Even if this third category does not fully encompass the demands of the BLM movement, which encompass a much broader range of issues than corporate DEI, actions in this category are more far-reaching, ambitious, and transformative.

In sum, various criteria can be used to distinguish “cheap talk” from deeper and more transformative action. Key elements are (1) alignment of private goals and public statements, (2) meaningful rather than symbolic actions that involve (3) real resources and organizational change, and (4) some degree of stickiness in this new orientation. Footnote 19

Between progressive neoliberalism and transformative change: An outline of the argument

I argue that the Equality of Opportunity Initiative (EOI) of the US Chamber and state- and regional-level chamber initiatives have the potential to help address problems of racial inequality and racial resentment. The chamber's EOI seeks to help overcome barriers that have prevented African Americans from participating in the American economy as business owners/entrepreneurs, managers, and workers. As such, it can be characterized as next-generation progressive neoliberalism, or progressive neoliberalism 2.0. In certain respects, the US Chamber's EOI goes beyond a progressive neoliberal vision of nondiscrimination: the US Chamber has acknowledged that it is necessary to take action to help “level the playing field.” This raises the question: Can the US Chamber reorient some of its massive lobbying war chest and lobbying power, which has grown vastly in recent decades,Footnote 20 to combat racism and racial inequalities? To date, the US Chamber's support of legislation to help close race-based opportunity gaps seems largely symbolic when it is compared to the organizations’ broader lobbying activities against the social regulation of the economy, but the existence of this legislative agenda gives the initiative some credibility.

Cheap talk, symbolic politics, and identity capitalists have certainly not disappeared, and the similarities between the US Chamber's EOI and current DEI efforts, on one hand, and Chamber and business DEI stances in the 1960s and 1970s, on the other, raises the question of whether current efforts can succeed where previous efforts have failed. This article nevertheless draws attention to sincere, bold, and, in some cases, costly action by American business leaders to advance the cause of racial equity. Among American business organizations that are explicitly committed to addressing racial inequalities, there is near-universal agreement on the nondiscrimination principle. But as I describe, some state- and regional-level chambers of commerce have made bold and genuine attempts to push beyond this realm to advance racial equity. Leong suggests that there are opportunities for preventing identity capitalism “if we're willing to be uncomfortable and do difficult things because they are right,”Footnote 21 and the following text provide examples of American business leaders who are doing just that. The Joplin Area Chamber of Commerce in Joplin, Missouri provided bold and outspoken support for BLM, which led to a backlash and social movement-oriented politics that helped to diversify the Joplin chamber's membership. Other chambers have pushed the envelope with racially progressive positions. Much evidence suggests that popular mobilization and social pressure following George Floyd's brutal murder was a turning point or critical juncture that enabled and accelerated this progress.

Before proceeding, I detail my research methods. In the absence of existing literature on the responses of the US Chamber and chambers of commerce to BLM, one of the main contributions of this article is to provide a rich empirical description of this phenomenon. In “circumstances where knowledge of a topic is minimal,” description is of fundamental importanceFootnote 22—in “order to do good social science … you need solid empirical data.”Footnote 23 This article draws on archival researchFootnote 24 and semistructured interviews, a “potentially invaluable tool for collecting data”Footnote 25 that is frequently recommended for theory building and shedding light on new and unexplored topics. Interviewing “is hard to do well,” and the quality of the interviews is decisive.Footnote 26 These challenges are particularly serious with business elites, a population that is well versed in techniques of impression management.Footnote 27 Readers can judge whether the author's efforts bore any fruit. Approximately two dozen interviews were conducted with US Chamber officials; chamber CEOs, presidents, and staff; as well as businesspeople and nonprofits in 2021–22; these are listed in the appendix. I have supplemented these interviews with evidence of action and historical contextualization whenever possible. While this evidence is imperfect, I hope that it provides a foundation that others can build on with more systematic and representative data.

The article is organized as follows. The next section discusses the US Chamber's National Summit on Equality of Opportunity and its EOI. I then place current American business responses to BLM in a historical context by comparing the EOI and current DEI efforts with US Chamber stances in the 1960s and 1970s as well as Nixon's Black capitalism movement. I then turn to the actions and responses of state-level and regional chambers of commerce, including Joplin, Missouri. The section on theorizing strategic considerations of American business responses to BLM is followed by a conclusion that reflects on the wider implications of the argument and on the lessons learned.

The US Chamber's National Summit on Equality of Opportunity and Equality of Opportunity Initiative

One month after Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd, the US Chamber convened its National Summit on Equality of Opportunity. This online town hall forum on equality of opportunity gaps was attended by ~6,000 business and other users.Footnote 28 At the opening of that event, the outgoing US Chamber CEO Tom Donahue stated:

We fundamentally believe that all Americans should have the opportunity to earn their success, rise on their own merits and live the American dream. But we know today that is not the case. Too many are held back by the color of their skin. Many black Americans are deeply limited by inequalities in our education health care housing and the criminal justice system. Too many face insurmountable barriers.

Donahue stressed the need to take action to ensure the “dignity of every man woman and child” and to take “long overdue” action to close opportunity gaps: “Our responsibility to serve our country at this moment in history is very important.”

The CEO of AT&T Randall Stephenson remarked: “It's a moral obligation; this is an issue of justice. What we are dealing with,” he maintained, “is patent pervasive injustice as it relates to the black community and the interactions with law enforcement.” “Corporate American cannot sit this one out.” Summit participants went on to stress the “structural disadvantage that is holding back black children, workers, business owners from truly reaching their potential.”

Participants acknowledged that <1 percent of Fortune 500 CEOs are Black; that it is necessary to increase the overall pool (overall Black representation in American business), rather than hire it away; that a lack of capital is a barrier for African American business growth. US Chamber President Suzanne Clark concluded the event by stating that the goal is to “create a powerful movement…. Business is a force for good…. We can and must be a champion for all.”

Rather than the public relations spin and defense of the status quo one might expect from a powerful lobbying organization, the US Chamber's National Summit on Equality of Opportunity presented a refreshingly sober assessment of the glaring socioeconomic and racial inequalities in the United States. This event kicked off the EOI, to which I now turn.

The US Chamber of Commerce's EOI has two strands, states Rick Wade, who leads the US Chamber's EOI and has served as Senior Vice President of Strategic Alliances and Outreach at the US Chamber since 2018: “Part of the EOI is advancing policies. The other part of it is advancing private sector solutions.”Footnote 29 Wade remarks that as an “Obama Democrat,” working for the US Chamber “was not part of the career trajectory or plan.” Wade's journey into the US Chamber began when he met Susanne Clark, the current president and CEO of the US Chamber, in Philadelphia at the 2016 Democratic National Convention. Clark asked Wade to become involved with the chamber, and he set out to think strategically about how the chamber can “be inclusive” and “become more engaged with diverse communities across America.”Footnote 30

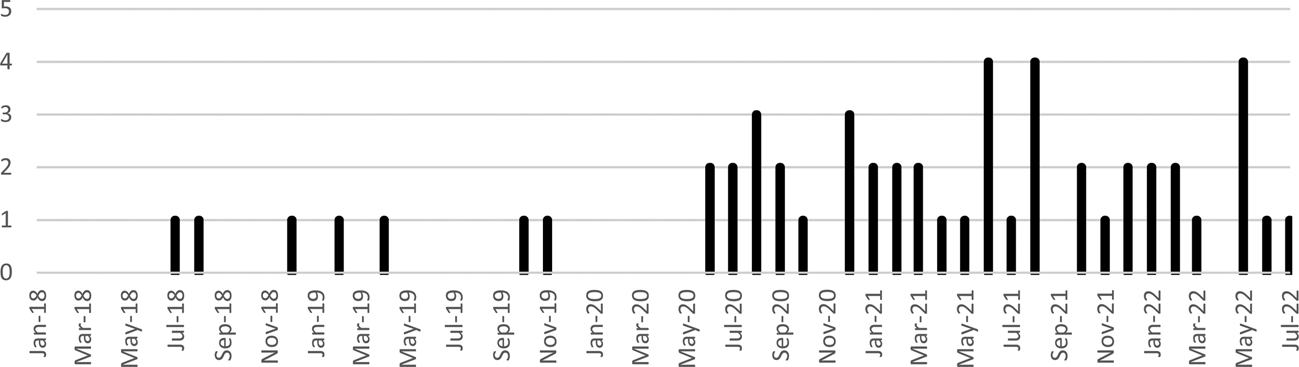

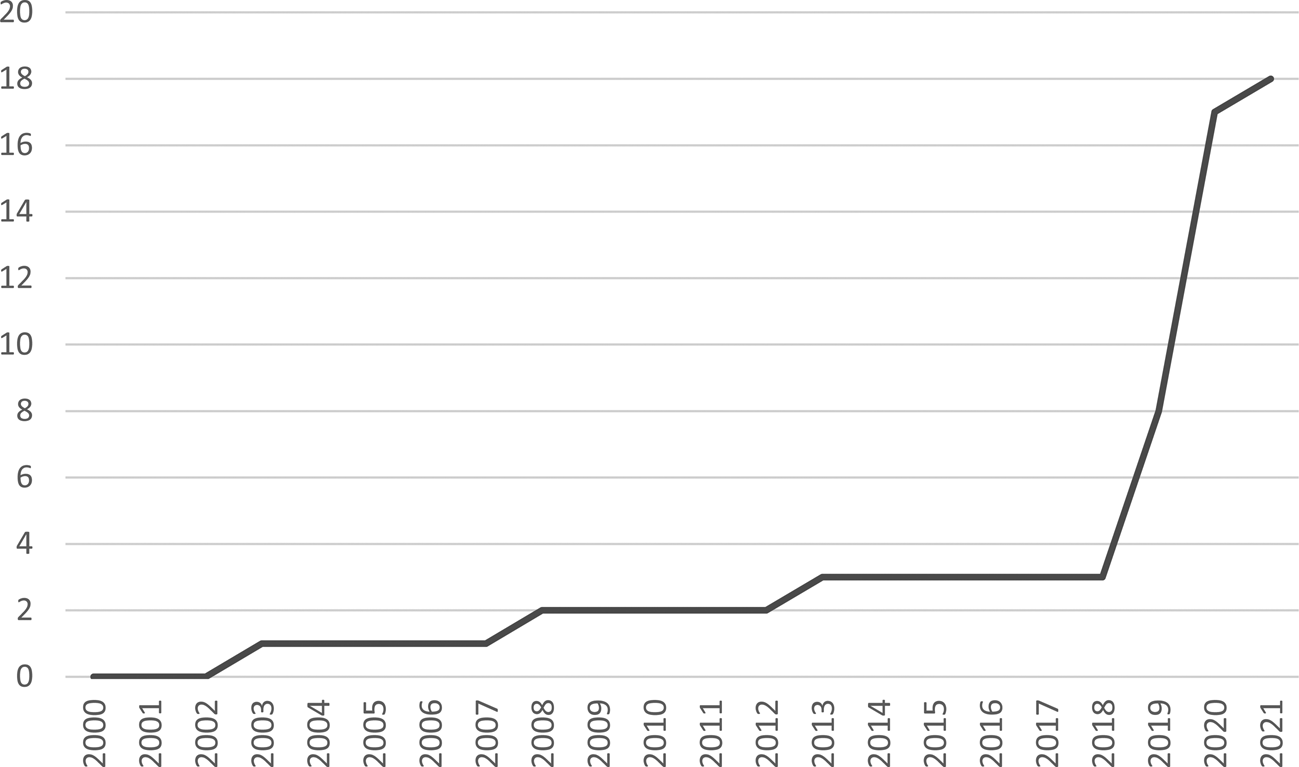

Wade, who has been working full-time for the US Chamber since 2018, stresses the importance of “timing” and the murder of George Floyd for advancing the EOI agenda: “Even if you had been engaged before the tragedy of George Floyd,” he recalls, business engagement “increased exponentially” following Floyd's murder: “In a time that was about the murder of George Floyd and the pandemic that was disproportionately affecting black and brown people the consciousness of these issues was at an all-time high.” Wade “decided that the Chamber had to be a leader in this moment in time. This was a historic moment that was a critical turning point in our recent history.” Wade was convinced that the chamber “had to step up at this leadership moment.”Footnote 31 As we can see in Figure 1, the frequency of chamber EOI-related press releases increased significantly following Floyd's murder on May 25, 2020:

Figure 1. Number of EOI-related press releases 2018–22.

Note: This figure shows the number of pieces from each month posted under “Latest Content” at https://www.uschamber.com/major-initiative/equality-of-opportunity-initiative Accessed on 26 August 2022.

Readers may wonder whether the EOI should be taken seriously, which is understandable, as Wade remarks: “The chamber didn't have a lot of street credibility in this space.”Footnote 32 The US Chamber has opposed the civil rights movement in the past.Footnote 33 However, the fact that the US Chamber now publicly encourages members of Congress to cosponsor legislation to address systemic inequalities in education, employment, entrepreneurship, criminal justice, health, and wealth development—that it is putting some of its “lobbying muscle” behind legislation that can help to reduce structural inequality in opportunity gaps—adds some credibility of the EOI initiative.Footnote 34 To date, the US Chamber has thrown its weight behind more than 20 EOI-related pieces of legislation on Capitol Hill. Regarding private-sector solutions, in partnership with the National Association of Corporate Directors, the chamber has committed to identify, prepare, and connect 250 Black executives to corporate boards by the end of 2022. This board diversity initiative is “a specific tangible private sector effort to try to deal with the gaps.”Footnote 35

The programmatic orientation of the EOI strongly foregrounds the business case; it uses an economic lens to analyze racism, and it stresses the benefits for business and society that can be attained by overcoming race-related inequalities. To be sure, Wade remarks, “We understand the moral imperative: it's the right thing to do…. The moral case is 100% the moral case,” which “we fought for 400 years.” However, Wade stresses that the business case for racial equity “became a centerpiece” of the case he made at the US Chamber. Wade's thesis is:

If we can articulate race in a way that folks understand the economic value…. The money we are leaving on the table or off the table…. There is a measurable economic benefit, it is not a zero-sum game. We all win by addressing these inequalities in America…. If we address the racial inequalities in America, the GDP grows by 8 trillion dollars.Footnote 36

The eight trillion dollar figure refers to the potential gains that could be achieved by 2050 if the United States is able to close the racial equity gap, according to a study by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation.Footnote 37 Along these lines, Wade points to studies showing that more diverse and inclusive companies are more profitable, and that addressing racial inequalities can help make the US economy more competitive.Footnote 38 It is easy to see how this agenda finds support in the business community.

A national network of approximately 500 state and local chambers of commerce have signed on as members of the EOI. “That powerful infrastructure and backbone across America gives us reach.” Wade explains what it means that they signed onto the EOI as partners: “They signed on that they would start that same conversation in their state and local communities. Begin a dialogue and put in place an equality of opportunity agenda.” Wade stresses the need to “Get to work advancing real policy and private sector solutions rooted locally.” Thus, it is not necessary for chambers to focus on all EOI areas, “In your local community you may decide to just focus on one. The point is: get in on the game!”Footnote 39

One of the notable characteristics of the EOI is the top-level support this initiative has received from the chamber's new leaders. “This work is the whole of Chamber effort,” Wade says of the EOI. Chamber President and CEO Suzanne Clark supports this agenda—Wade states that he and Clark “always had a shared understanding and shared values.”Footnote 40 Wade worked with the entire executive leadership team, and especially Neil Bradley, the chamber's Executive Vice President and Chief Policy Officer, as well as Michelle Russo, the Chief Communications Officer—together, these three people are the architects of the town hall forum and the EOI.

Wade avers that he's “trying to get something done: how do we sustain that and make it not a moment but a movement? How do we make it not just a conversation but real action? That's what this agenda seeks to do.” Under Wade's pragmatic and charismatic leadership, the US Chamber has committed to making substantial progress advancing equality of opportunity. “It's the moral thing to do, it's the right thing to do, it's good for our economy…. Let's get out of our boxes put our cards on the table and build a better America.”Footnote 41

In the absence of systematic data regarding EOI-related progress, we are forced to speculate about the effectiveness of this endeavor. Can the power of private enterprise and the carrot of economic benefits help the country to overcome racial resentment? Can the chamber wield its formidable lobbying power to advance meaningful institutional reform? Can the chamber's EOI succeed where previous efforts have failed?

To get a sense of EOI related action at the time of writing, I spoke with Marcel Bucsescu, the senior director for credentialing and strategic engagement at the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD). The NACD has been working on diversity and inclusion for a long time. It is difficult to get underrepresented groups into boardrooms and change boardroom culture, Bucsescu points out.Footnote 42 Concerning Board Diversity Accelerator Initiative, which is a collaboration between the NACD and the US Chamber, Bucsescu lauds the “almost organic collaboration” with his counterparts at the US Chamber. Concerning the progress that has been made on this initiative, which was set up at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in November 2020, as of mid-March 2022, 147 Black business executives had participated in the program. Considering this, the 250 goal by the end of 2022 “is a little ambitious.” “We have more work to do,” “we aspire to do more,” Bucsescu concludes.Footnote 43 The next section provides some historical context for current initiatives by examining US Chamber stances in the 1960s and 1970s as well as Nixon's Black capitalism movement.

Comparing the US Chamber's Equality of Opportunity Initiative with efforts in the 1960s and 1970s including Nixon's Black capitalism movement

Pressures to address racial inequalities are not new, and business initiatives to address racial disparities are not as novel as they may seem. This section draws on archival research and secondary literature to suggest that there are considerable parallels and similarities between the US Chamber's EOI and current DEI efforts on one hand and US Chamber and more general business efforts in the tumultuous 1960s and 1970s.

In the brochure “Corporate Options for Increasing Minority Participation in the Economy” published in 1970, US Chamber President Arch N. Booth wrote:

The National Chamber of Commerce believes that the opportunity to become a business owner—to succeed or fail in a business—should be available to all…. Few businessmen will argue against the need for all of the Nation's institutions to make it possible for all of our people to have an equal opportunity to participate in the economic system. Many businessmen want to help to open such opportunities.Footnote 44

The chamber laid out “Corporate Options for Increasing Minority Participation in the Economy”:

-

Step One: The Commitment of Top Management

-

Step Two: Involvement of the Organization

-

Step Three: Involvement of the Community

-

Step Four: Organizing for Action

-

Step Five: Identification of Resources

-

Step Six: Determination of PrioritiesFootnote 45

The chamber presented action items such as management training programs, loans, credit, financing, and venture capital for minority businesses. These remain a major focus of DEI today, half a century later. The chamber stressed that these “goals and priorities should be a plan of action rather than a public relations gimmick.”Footnote 46

The chamber provided a clear rationale for this agenda: “It is to the advantage of the community, and the Nation as a whole, that a greater proportion of minority groups seek self-employment and entrepreneurship as a career objective.” The chamber encouraged businessmen and organizations “to learn more about such efforts and to explore ways in which they may cooperate in the encouragement of and the development of entrepreneurship among minority groups.”Footnote 47

As we can see in the following excerpt, considerable social pressure motivated chambers to address these issues:

Where chambers are not doing so, business and professional people need to reappraise the basic role of their chamber in the community. The day when local chambers can limit their activities to promotion or to economic issues is past. The times demand broad business involvement in community affairs through modern chambers of commerce, organized and staffed to lead and support such involvement.Footnote 48

In the remainder of this section, I discuss the broader political context—more specifically Richard Nixon's Black capitalism initiative between 1968 and 1972—and the impact of these initiatives.

When he was running for the presidency in 1968, Richard Nixon used “black capitalism” to get more Black votes.Footnote 49 Nixon supported “black capitalism” to promote “black ownership … black jobs, black opportunity … a share of the wealth and a piece of the action.”Footnote 50 Nixon established the Office of Minority Business Enterprise (OMBE) to increase funding for and expand federal procurement from African American– and Hispanic American–owned businesses. His goal was to co-opt Black Power, “an oppositional, but elastic, concept which the Republican candidate stretched into a mainstream proposal for black capitalism.”Footnote 51

Black capitalism was not uncontroversial: It was critiqued by anticapitalists and antinationalists. In his book Black Awakening in Capitalist America, opponent Robert Allen wrote that “The corporatists are attempting with considerable success to co-opt the black power movement.… Their strategy is to equate black power with black capitalism.”Footnote 52 Much like BLM today, within the “black capitalist movement,” there were voices who supported stronger welfare programs, income redistribution, and an “‘economic bill of rights’ that demanded a redistribution of wealth and a guaranteed minimum income for American families.” But there were also those who did well for themselves who supported entrepreneurship and free enterprise.Footnote 53

While some were genuinely committed to Black capitalism, others saw it as a political ploy.Footnote 54 For the latter, the program was symbolic and a public relations strategy—the goal was to create success stories.Footnote 55 According to Baradaran,

Ultimately, black capitalism was anemic and utterly unresponsive to the needs of the black community. But it was vague enough to offer just the hope needed to cool the anger as it was about to spill over…. The harvest of black capitalism was the retreat of the black radical groups from center stage and the emergence of a more pragmatic, moderate, and “business-oriented” black leadership.Footnote 56

Black capitalism was not the only project that sought to promote African American entrepreneurship and enterprise in this era. Operation Breadbasket in Chicago (1966–71) had similar goals, and despite its much smaller scale, it contributed toward the economic advancement of African Americans by generating 4,516 jobs for them in Chicago. By 1971, “the black community of Chicago was gaining $57.5 million annually from Operation Breadbasket's justice work. These dollars translate into $319.8 million in the 2016 economy.”Footnote 57

In the end, these initiatives did not significantly increase entrepreneurship or property ownership among people of color; yet one should not underestimate their attractiveness for some African Americans. As Beltramini observes, “[M]ore than the desire to end poverty, black families yearned to be consumers in an affluent society. They did not contest capitalism, only their exclusion from it.”Footnote 58 For the White socioeconomic elite, Black capitalism was undeniably useful as it “turned out to be a very effective antidote to militant black uprisings.”Footnote 59 While Black capitalism did not achieve its stated objectives, it did succeed in subverting African American radicalismFootnote 60 and the threat it presented to the interests of the dominant class: The radical voices that emerged from the Black liberation movement of the 1960s “were not content with talk of shattering glass ceilings,” instead, they wanted to shatter the system.Footnote 61

To sum up, half a century before the EOI, the US Chamber of Commerce expressed support for equal opportunity, management training, and financing to promote minority businesses. Although further historical research is needed, it appears that the US Chamber did support Nixon's Black capitalism movement.Footnote 62 Nixon met with chamber leaders at the White House, and a Telecast dialogue with 20,000 business and community leaders from across the country on urban problems was reportedly a “smash hit.”Footnote 63

Several lessons emerge from this section: In both historical periods, the chamber responded to popular mobilization by accommodating social pressure and advocating for business and market-friendly measures to help mitigate racial inequalities. However, with the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that the US Chamber and related DEI efforts in the 1960s and 1970s had a very limited impact. The circumstances and events that gave rise to BLM in the 2010s are a sobering testament to the failure of these efforts. Insufficient resources, organizational stickiness, and limited follow-through may have contributed to this outcome. Whether the institutionalization and organizational backing of the EOI will be sufficient to overcome the obstacles that stood in the way of previous efforts to advance racial equality is unclear. The US Chamber and chambers across the country should carefully study their own history and previous involvement with DEI-related initiatives to learn lessons for the present.

The actions and responses of state-level and regional chambers of commerce

The US Chamber of Commerce is a powerful lobbying force in Washington, D.C., but progress against racism will be limited unless it takes place in local communities, businesses, and state capitols across the country. This makes the activities of regional- and state-level chambers so important. Is there anything of substance going on here?

To answer this question, this section provides a first cut or cursory survey of the EOI and DEI-related activities of state-level chambers of commerce in Florida, Georgia, Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, as well as regional chambers in Bentonville, Arkansas; Harrison, Arkansas; Chattanooga, Tennessee; and Loudoun County, Virginia. This is not a random or representative sample, but it does provide a glimpse into what some engaged chambers are doing to advance DEI. Many of these chambers are in states with comparatively high state-level racial resentment scores.Footnote 64 If business leaders around the country are taking meaningful action, perhaps some real progress can be made.

I use the evidence in this section to make five points. First, the examples in this section show a great deal of diversity regarding the chambers’ approaches to advancing the DEI and EOI agenda. These approaches include race equity training, CEO Pledges for Racial Equity, legislative action on criminal justice reform and hate crimes, and broader approaches that seek to tackle childhood poverty and inequalities of opportunity at the state level. This diversity is a strength, not a weakness, as a one-size-fits-all approach would be less well attuned to local peculiarities and lead to a lower participation rate.

Second, chamber leaders emphasize the benefits of EOI-related activities for business and for attracting employees and highly skilled professionalsFootnote 65 during the current labor shortage. Third, the examples that follow show that some chambers are pushing the envelope and taking racially progressive positions that go beyond what some of their member companies are willing to support. This suggests that some chamber and business leaders are trying to engage in meaningful change. Fourth, there is almost universal agreement that the murder of George Floyd prompted chambers and businesses to take more and bolder action than they had been doing up to that point.

The origins of the Florida Chamber Foundation's Florida Equality of Opportunity Initiative (FEOI) reach back to 2015/2016, when Florida Chamber President & CEO Mark Wilson stressed the importance of economic opportunity as opposed to economic equality. While this implies a clear rejection of the left-wing or progressive populist agenda, it does not represent a bare-bones endorsement of nondiscrimination. As Kyle Baltuch, who serves as Senior Vice President of Equality of Opportunity at the Florida Chamber Foundation, points out, it is often said that people should pull themselves up by their bootstraps. The problem with this is that many people (for example children) don't have bootstraps.

Accordingly, the FEOI focuses on childhood poverty, educational quality and outcomes, and workplace diversity throughout Florida. Like the US Chamber's EOI, the FEOI foregrounds the economic and business rationale for investments to reduce barriers to opportunity: “Childhood poverty is a constraint on economic growth.… Children in poverty today are the workforce of tomorrow…. The talent of the future will be more diverse.”Footnote 66 The overall normative vision of the FEOI is one in which “everyone has a seat at the table and a legitimate equal opportunity for earned success.” In addition to reducing childhood poverty, the FEOI aims to ensure that 100 percent of third graders in Florida are reading at their grade level.Footnote 67

The FEOI's distinctive approach is to measure indicators such as childhood poverty and educational outcomes in every zip code in Florida, to facilitate cooperation between different stakeholders and target resources and problem-solving capacities in the most efficient and effective manner. Eventually, the hope is that best practice models will be found that can be replicated. While the business case is clearly central for the FEOI, it is informed by an aspiration to “slap business leaders in the face with reality and how it impacts them,” and a realization that “everyone does not have an equal opportunity to succeed. Let's do something about it!”Footnote 68 “It is our responsibility as Americans to ensure that everybody has the opportunity to succeed.” George Floyd's murder “supercharged” the FEOI and led to a more holistic approach and a realization that “issues are deeply interconnected.”Footnote 69

The FEOI is ambitious in its goals to reduce childhood poverty, improve educational outcomes, and champion diversity and inclusiveness in Florida workplaces.Footnote 70 As the FEOI evolves, the Florida ScorecardFootnote 71 is being expanded to include up to 70 different indicators, which will allow those involved with the FEOI to diagnose and perhaps address the specific problem(s) faced by inhabitants of each zip code. In addition, the FEOI is working on incentivizing new coalitions to work together. Reflecting on what has led certain zip codes to pull ahead and make progress, Baltuch states that “one needs a strong business leader and a chamber that's willing to participate.”Footnote 72 The importance of strong chamber and community leadership becomes clear in the section on Joplin, Missouri.

A focus on diversity and inclusion has been part of the Georgia Chamber of Commerce's (GCC)'s DNA since 2016, when the GCC began to increase its engagement with minority business partners and members. By now, its annual DEI summits are among the largest events organized by the GCC, remarks GCC President and CEO Chris Cark.Footnote 73 In addition, the GCC is providing platforms for DEI networking and programming, which will soon include a DEI training course for rural leaders. In addition to encouraging and supporting the DEI councils of local chambers, the GCC has helped to pass legislation on hate crimes and repeal citizen's arrest legislation. “We have been told that our engagement was crucial for passage,” remarks Clark.Footnote 74 There has been “just a little” bit of push back against these initiatives: “No one wants to engage in these efforts in a reactionary context nor are many interested in being ‘woke.’ Most want and like our fact driven–long term prosperity focus.” Concerning the influence of George Floyd, “We were working here prior to Floyd but that incident did provide motivation from many companies to engage.”Footnote 75

Following Floyd's murder and the unrest that followed, calls came in from small businesses owners who asked: “What can and what should we do?”Footnote 76 recalls Christine Ross, who served as president and CEO of the Maryland Chamber of Commerce (MCC) from 2016–21. Only a few weeks later, the MCC launched a six-part webinar series to showcase best practices for developing strategies to promote DEI in the workplace. Ross stresses the important role this initiative has had in spreading best practices from large best-in-class firms to small members of the chamber, as well as allowing “hundreds of business leaders to normalize a conversation they didn't even know how to start.” The MCC is prioritizing an EOI-inspired legislative agenda, which includes the Second Chance Task Force to promote the integration of ex-offenders into the labor market.Footnote 77

The Pennsylvania Chamber of Business and Industry (PCBI) has a strong focus on criminal justice reforms. In 2019, Pennsylvania was the first state to pass clean slate legislation, which serves to seal certain criminal records from public view, thereby helping people with criminal records, which includes a disproportionate number of African Americans, to get jobs. This legislation passed with the support of the PCBI. Gene Barr, President and CEO of the PCBI, states that he “like[s] what Rick [Wade] is doing with EOI. We can't guarantee outcomes, but we should be able to be sure that we give equality of opportunity.”Footnote 78

Barr points out that criminal justice reform “helps to get additional people into the workforce.” “For us, in addition to the workforce side, it seemed like the right thing to do from a moral basis to give people a second chance.” In promoting this legislation, the PCBI worked together with the REFORM Alliance, the Justice Action Network, and other civil society organizations. This work was facilitated by a convergence of political interests: a push from the left from a fairness perspective and from the right, the rising cost of incarceration. As we will see, some companies are having substantial success hiring reentry candidates. In addition, the PCBI is prioritizing affordable childcare and transportation that disproportionately affect African Americans and can help bring more people into the Pennsylvania workforce. As Barr points out, the overriding goal is to “bring as many citizens forward as we can.”Footnote 79 Economic and business interests can lead chambers to take meaningful action.

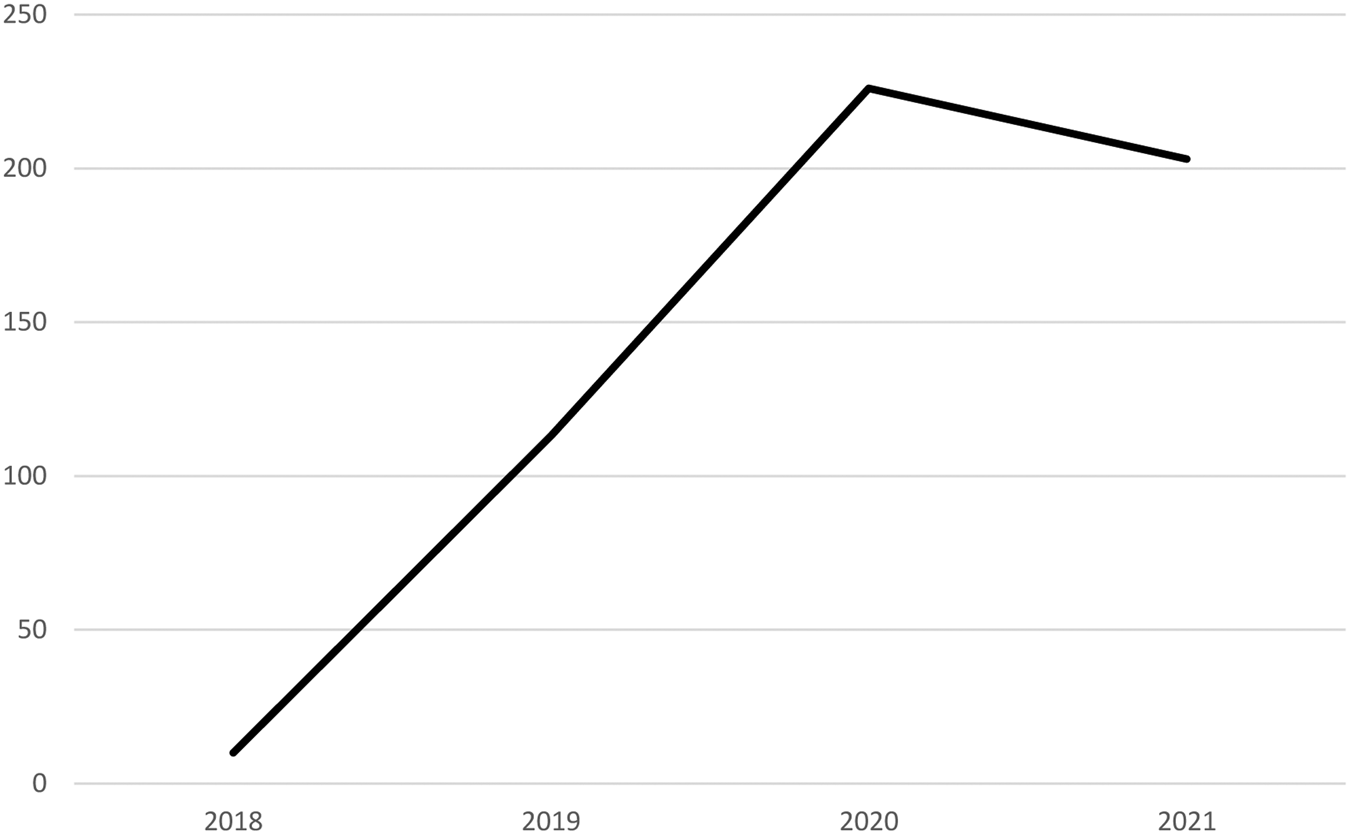

Due to space constraints, this article can only provide a glance at what companies are doing to promote the EOI agenda and address racial and socioeconomic inequalities. Flagger Force, a traffic control company headquartered in Pennsylvania, provides a good illustration. Since this company was established in the early 2000s, it has hired formerly incarcerated people, and this program was formalized in October 2018. Flagger Force's reentrants tend to be of lower socioeconomic status, and often have less than a high school education. Seventy-five percent of this population identify as an ethnic or racial minority.Footnote 80

Figure 2. Number of reentrants employed by flagger force in its 2nd chance program from 2018–21.

Source: Flagger Force.

To date, Flagger Force has employed more than 550 reentrants in its 2nd chance program (Figure 2). From the company's perspective, this program is a successful talent acquisition strategy; for formerly incarcerated individuals, who are disproportionately minorities, this program provides a welcome and all-too-rare chance to regain a foothold in the labor market. When workers are in short supply, companies may become proactive in hiring minorities, including ex-offenders. By doing so, companies can help to reduce racial and socioeconomic inequalities.

The New Jersey Chamber of Commerce (NJCC)'s EOI agenda is closely informed by the US Chamber's template. While the chambers in Maryland and Pennsylvania have prioritized criminal justice reform, the NJCC has decided to move forward by creating a diversity and inclusion committee and by intensifying its cooperation and partnership with the African American Chamber of Commerce of New Jersey.Footnote 81

Lorne Steedley began his work as Vice President for Diversity and Inclusive Growth at the Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce (CACC) in November 2020. Among other things, he was tasked with delivering of a CEO Pledge for Racial Equity. Steedley researched best practices and came up with a pledge that was delivered to many local business executives in spring 2021. This pledge stresses the need for “open and candid conversations” “to overcome challenges created by centuries of unequal access to opportunity.” It reads:

We will educate ourselves and share the history of systemic racism in Chattanooga and Hamilton County and the barriers that continue, so that as we recognize them, we can find new ways to overcome them…. We will use our influence and position to amplify unheard voices and support policies that lead to racial justice…. We will improve the employment, training, advancement, support, and success of people of color in our workforces. We will evaluate contracting and procurement efforts with the intention to grow and expand business participation of marginalized businesses of color. We will continue our work by engaging in CEOs for Racial Equity meetings to address the issues of racism, injustice and bias in our organizations and community.Footnote 82

In my interview with him, Steedley provided many business reasons to embrace this agenda, including its necessity for maintaining economic viability; the existence of large, dynamic, and expanding markets in Africa; and the importance of this agenda for talent acquisition and retention. How have member companies of the CACC responded? Steedley states that he got “a lot of support but also questions.Footnote 83 Seventy businesses signed the pledge.Footnote 84 The fact that many business leaders have yet to sign the pledge can be seen as an indication of indifference or of continuing racial resentment or fear of backlash the current polarized environment; but the fact that many businesses have been hesitant to sign could also suggest that it is not empty, hollow, or meaningless.

Arkansas does not have a reputation as a racially progressive state; in 2016, Arkansas had the highest state-level racial resentment score in the United States.Footnote 85 One might therefore view Arkansas as a most likely case for nonresponses, cheap talk and symbolic politics, and a least likely case for bold chamber support of BLM. Yet the examples in the following text suggest that both interests and values have prompted chambers in Arkansas to take action to advance the cause of racial equity.

Graham Cobb, who served as president and CEO of the Greater Bentonville Area Chamber of Commerce (GBACC) from 2017–22, points out that Bentonville in northwest Arkansas has “not been a historically diverse region. Over the past few years that has changed.” Many Fortune 500 companies have their headquarters in Bentonville and, recently, Bentonville has been one of the fastest-growing counties in the country. It is hard to overestimate the importance of Walmart's influence, as the world's largest retailer, on the GBACC's support for equality of opportunity: “[O]ur largest employer needs the most talented people to come here and call it home…. The Chamber has to play a role.… Some of the smartest people in the world are coming to Arkansas,” remarks Cobb.Footnote 86

During the past years, the GBACC has deepened and accelerated its DEI focus. When he got started on this, Cobb recalls, “We need to do some work” to get up to speed, “not just start off with statements that sound hollow. We don't have a plan we don't know what needs to be done.” The GBACC's focus on underrepresented groups, which includes race equity training as well as legislation to prosecute hate crimes, has grown since Floyd's murder. Ben-Saba Hasan, Walmart's Chief Culture Diversity Equity & Inclusion Officer sits on CBACC's board and is an important influence. In addition, “We can learn from the Walton family who are laser focused on access,” Cobb remarks. “This is an economic issue…. Systemic racism is an economic constraint.”Footnote 87 Bentonville is unique in Arkansas, and few chambers across the United States can draw on comparable resources to promote DEI and attract high-skilled, highly educated professionals. But this example illustrates the relevance of the business case even in states with comparatively high levels of racial resentment. When “doing what's right for business” is “seeking equitable opportunity,” “chambers [can] play a unique and valuable role” by allying with underrepresented groups and supporting DEI.Footnote 88

Since 2019, Bob Largent has served as president and CEO of the Harrison Regional Chamber of Commerce (HRCC), approximately two hours east of Bentonville. Largent was tasked with developing and implementing a strategic plan for economic development—a first for the organization—in which diversity and inclusiveness are an integral part: “We're all about creating jobs, opportunities and prosperity for the whole community.”Footnote 89 This entailed the creation of a Diversity & Inclusivity Committee. Harrison has been labeled the “most racist town in America” in a viral YouTube video that has racked up more than 10 million views. As the HRCC responded to the challenge of rebuilding Harrison's reputation, the organization condemned racism, hatred, and bigotry and expressed support for a hate crimes law. While some people in Harrison and in nearby areas are bigots and racists, Largent stresses that most are not. As the HRCC has countered bigotry and racism, it has built upon the practices of member companies such as FedEx Freight, for whom diversity is an important part of their corporate culture.Footnote 90

By spring 2022, the HRCC's DEI efforts had exceeded what one would expect of an organization with modest resources that was merely seeking to minimize reputational damage. Activities in 2021–22 included an event with NBA All-Star Sidney Moncrief to “educate on and experience diversity and inclusion.” In addition, the HRCC hosted the first ever community wide Unity in the Park event, together with DuShun Scarbrough, the Arkansas Martin Luther King Jr. Commission, George Floyd's uncle Selwyn Jones, and others. HRCC has hosted the statewide MLK Jr. Day event and has encouraged HRCC member companies to highlight Juneteenth. Thousands of people have been impacted and influenced. Amy Deere, who is responsible for organizing DEI events at the HRCC, takes her work seriously:

I am so proud of the work I am privileged to collaborate on here at the Chamber…. This is not effortless or unintentional work. Working on DEI and trying to help with DEI education and opportunities for a community is not something you work on for a short period of time, putting in the smallest amount of effort, and expect to be done. DEI work done anywhere should be recognized as an ongoing effort to learn and work toward change to help improve lives.Footnote 91

The HRCC's DEI activities are notable considering Harrison's overwhelmingly White demographics.

The business case for DEI is also prominent at the Loudoun County Chamber of Commerce (LCCC), near Washington, D.C. The LCCC's push to promote DEI began in 2019. The initial impetus was to diversify the LCCC as an organization, including the LCCC's own board of directors, to better reflect the growing diversity in Loudoun county and improve the organization's own performance, remarks Tony Howard, the LCCC's President & CEO.Footnote 92 This reflects a growing consensus that DEI is “good for business!” Along these lines and since the war for talent is “fierce,” the LCCC is working to provide its members, including small businesses, with a “toolkit of best practices.” Floyd's murder was a “moment of racial reckoning” for the country and, following it, Howard issued a thoughtful statement, denouncing the “clear criminal act carried out by officers of the Minneapolis Police Department and drawing attention to “centuries of oppression and terror here in America…. It is no longer enough for this Chamber to simply oppose inequality, injustice, and discrimination. It is time for us to act.”Footnote 93

A substantial number of chambers of commerce across the country, including many in states with high levels of racial resentment, have taken similar stands following Floyd's murder. The next section of this article turns to the city of Joplin, where the area chamber has provided bold and outspoken support for BLM, at some cost to itself.

Bold chamber support for Black Lives Matter in Joplin, Missouri

One of the most notable examples of chamber support for BLM in this article can be found in the city of Joplin, in southwest Missouri. This example shows what loud, social movement–oriented politics is possible when chambers are willing to take bold action to advance racial justice. Two weeks after Floyd's murder, Tobias Teeter, who at the time served as CEO of the Joplin Area of Commerce, published “An Open Letter to Our Community.” This letter is remarkable for its bold language, frank diagnosis, and call to action. I excerpt portions of the letter here:

We at the Joplin Area Chamber of Commerce (JACC) are heartbroken and enraged by the continued, violent mistreatment of the Black community. The unjust and tragic murders of George Floyd and many others in the Black community cannot be ignored … we stand with Black people in the Joplin community and beyond who continue to experience violence and racism.

Meaningful changes and contributions will start with how we operate the JACC. For 103 years, the benefits and privileges of membership to this institution have been enjoyed, almost exclusively, by white business owners. And until a generation ago, almost exclusively, by white male business owners. We acknowledge our institution has been part of the problem of institutionalized racism and sexism where decisions, public policies, and business deals benefit the white privileged, thus reinforcing long-standing racial, gender, and class inequities.

I'm holding myself accountable. I'm holding the Joplin Area Chamber of Commerce accountable. This will include making changes to our hiring practices and employment manual to ensure equitable inclusion of people of different races, ethnicities, gender identities, sexual orientations, ages, social classes, and physical and mental abilities or attributes. Also, dedicating more resources to ensure Joplin's Black-owned businesses, entrepreneurs, and business professionals are included, supported, and championed.

Just as we acknowledge being part of the problem, the Chamber challenges area police departments, municipalities, businesses, schools, and nonprofits to (1) REVIEW your policies, procedures … (*This includes use-of-force reforms for our local police departments …); (2) ENGAGE your stakeholders … and (3) REPORT the findings of your reviews to your stakeholders and seek feedback for ongoing accountability and improvement to (4) REFORM your policies.

Regrettably, we cannot change the past but we should do everything we can to change the future of this nation. It starts here, in Joplin. It starts now, with us.Footnote 94

This is an unconventional letter for a business organization. Teeter says that he “thought this was a pretty clear opportunity to put a stake in the ground and say we can do better.”Footnote 95 What prompted him to write and publish this letter without prior consultation with the JACC board of directors?

There were background conditions or structural pressures that pushed him in this direction: there was “a huge labor shortage” in Joplin, and Teeter saw it as his job to “attract and retain this talent pool.” In Teeter's view, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) is an important tool to attract these people to Joplin. As important as these structural factors are, a meeting in the JACC's Leadership and EDI committee, which was chaired by Shonte Clay-Fulgham at the time, was the proximate cause.Footnote 96

That very emotional meeting took place shortly after Floyd was murdered. Participants asked, “where is our country going to go from here?” Teeter began by getting a take on everyone's feelings: “What was the temperature in the room?” At that meeting, Clay-Fulgham challenged Teeter and said: “If I am going to be part of this chamber, I need this chamber to say something and make a [public] statement.”Footnote 97 Teeter took a pen and wrote his Open Letter in one hour. His bold statement in support of BLM and the strong value orientation that underlies it resembles Max Weber's “ethics of conviction,” epitomized by what Martin Luther said at the Diet of Worms: “Here I stand; I can do no other.”

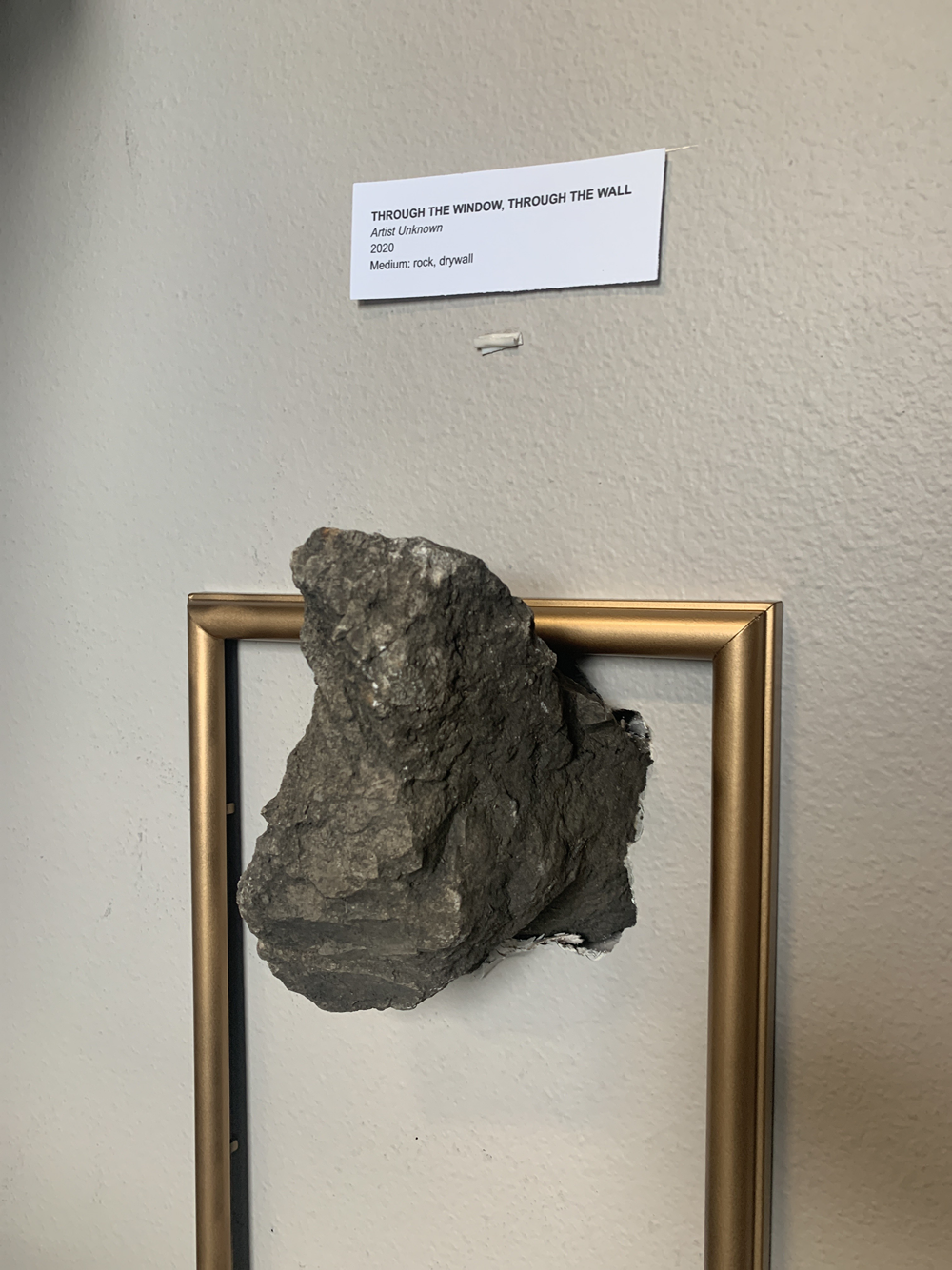

It did not take long for the backlash to arrive on Facebook; there were calls to boycott the chamber, and for Teeter to resign. He was threatened 15–20 times, and there were counterprotests that culminated in an antichamber movement. The JACC's board of directors was split and provided only tepid support. “They were not overwhelmingly joyously in the boat,” Teeter recalls. Before Teeter was scheduled to give a speech in front of the city council, a rock was thrown through the glass door of the JACC (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The entrance of JACC following the attack.

Source: Tobias Teeter, personal communication with author.

The attacker shoved the boulder into the drywall for effect (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Boulder in drywall of the JACC following Teeter's Open Letter to Our Community.

Source: Tobias Teeter, personal communication with author.

Approximately 40–50 White-owned businesses, a fair representation of the JACC across sectors and industries, canceled their membership in the JACC. These businesses exercised one of the most powerful tools that business has—the power of “exit” or disinvestment. “It was tricky times,” Teeter recalls.Footnote 98 That this pressure did not bring down Teeter is a testament to the latter's courage and leadership. “Thank goodness we have Toby!” exclaims Nanda Nunnelly-Sparks, who is involved in racial justice and social justice work in Joplin and who rallied the community around the chamber during this impasse. “Yes, it's about time! It's about time for this to be spoken out,” Nunnelly-Sparks says of Teeter's letter. Referring to the backlash, she says that “It got very ugly,” but “change is hard for some people and coming to terms with structural racism is hard.”Footnote 99

Then another remarkable thing happened: The community came out and rallied around the JACC. Many people attended the Unity Walk organized by the JACC following Floyd's murder (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Unity Walk organized by the JACC following Floyd's murder.

Source: Tobias Teeter, personal communication with author.

Nunnelly-Sparks asked: “Why are we boycotting something that is trying to right a wrong? Instead of boycotting the chamber let's bring ourselves, our dollars, our cents to the chamber.” Her specific idea was to help overcome barriers to access for Black-owned businesses that would like to get involved with JACC. She did this by “raising money to pay for [chamber] memberships” for these Black-owned businesses through the Langston Hughes society, an African American nonprofit based in Joplin. “If you're a small minority run business $500 is a lot…. That's how it began.”Footnote 100 The Langston Hughes society ended up paying for a substantial number of memberships, which contributed to a notable increase in the number of minority-owned businesses in the JACC between 2018 and 2021 (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Minority-owned businesses in the Joplin Area Chamber of Commerce, 2000–21.

Source: Joplin Area Chamber of Commerce, 2022.

Some supporters were willing to contribute resources, but not in public. Nunnelly-Sparks believes “that those people that left [the JACC] thought: the chamber is going to dissolve, there won't be anything left. But there are enough good people that we aren't going anywhere.” What began as a letter after Floyd's murder ended up as a social movement that to some extent reconstituted the JACC as an organization. Nunnelly-Sparks reflects on this dynamic:

It's always better to change something from the inside rather than from the outside and beating the doors down. For me, it's always better to work with people than to constantly work against. If they [the 40–50 white owned businesses that cancelled their memberships] are leaving and we are part of the chamber and they come back, they will be working with us…. The chamber has made itself more accessible. We helped the chamber, but the chamber is also doing things to help minority owned businesses as well.Footnote 101

Nunnelly-Sparks concludes: “There has been a shift in the community. It has opened up this conversation. I don't see it as being shut anytime soon…. I definitely feel we're moving forward toward greater racial justice.”Footnote 102 While Teeter and Clay-Fulgham have moved on to pursue other attractive job opportunities, the momentum of the EDI movement in Joplin continues: The JACC has launched an EDI Leadership Pledge which was signed by 24 local businesses in 2021 and 43 in 2022,Footnote 103 and “we took the pledge” door stickers can reportedly be found all over Joplin. The JACC Board has indicated that they want to continue these EDI efforts under the new Chamber President Travis Stephens.Footnote 104

In the absence of systematic data, it is unclear to what extent the JACC is representative of chambers across the country, and it is too early to know what the outcome of these initiatives will be; but this appears to be an extreme case of transformative, risky, and, at least in the short run, costly business action. What has been going on at the JACC goes beyond progressive neoliberalism and suggests that under certain circumstances, business organizations can be bold agents of transformative change by taking a loud public position in support of BLM and diversifying their own membership.

Theorizing American business responses to Black Lives Matter: Strategic considerations

In this penultimate section of the article, I return to the US Chamber to theorize American business responses to BLM in the broader contexts of American capitalism and its critics, business response strategies to political challenges, and different factions of BLM. As one of the world's most formidable business organizations, “The US Chamber of Commerce is notorious for waging big, dramatic fights in the public eye” against regulation.Footnote 105 Shortly after he became CEO of the US Chamber, Donahue stated: “My goal is simple—to build the biggest gorilla in this town—the most aggressive and vigorous business advocate our nation has ever seen.”Footnote 106 Until recently, the US Chamber of Commerce made “little pretense of bipartisanship.”Footnote 107 On the contrary: It has been a “hard right influence machine” “operating on a scale unprecedented in American history,”Footnote 108 the advocacy of which “has been a principal factor encouraging the GOP's long rightward march.”Footnote 109 A group of scholars submit that the US Chamber has been integral to the hijacking of Congress by corporate and monied interests.Footnote 110

On the face of it, the US Chamber's EOI is markedly different from previous instances of business mobilization when business launched a direct challenge—a frontal assault—on policies such as the New DealFootnote 111 and on the move toward greater social regulation of business in the postwar decades. Beginning in the 1970s, the US Chamber of Commerce and other leading American business organizations launched a “sustained intellectual and lobbying offensive”Footnote 112 that has substantially shaped politics, policy, and distributive outcomes in recent decades.

More than anything else, Lewis F. Powell's confidential 1971 memorandum “Attack on American free enterprise system” epitomizes this aggressive business stance. Powell implored business to:

Conduct guerilla warfare against those who propagandize against the system…. It is essential that spokesmen for the enterprise system—at all levels and at every opportunity—be far more aggressive than in the past…. There should not be the slightest hesitation to press vigorously in all political areas for support of the enterprise system.Footnote 113

Powell's goal was to defend and promote economic freedom and “the enterprise system.” Viewed in this general sense, there is some continuity between the Powell memo, DEI-related efforts in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and current business responses to BLM: One of the principal objectives of business advocacy in each era is to steer policy developments in a business-friendly direction.

To understand the distinction between aggressive business advocacy and more accommodative business responses to social pressures such as BLM, it is necessary to take the larger strategic context into consideration. Sometimes, business is on the warpath and can proactively set the agenda; but at other times, especially in moments of turbulence and crisis, it is necessary for business to swim with the tide while promoting its broader strategic interests. In both cases, business seeks to influence policy outcomes. Which role business plays depends on the strategic context and the political opportunity structure.

The US Chamber's EOI was not created out of nothing; shortly after Trump became president, the chamber began a strategic shift, an attempt to disentangle its brand from the GOP.Footnote 114 The chamber's EOI is part of this broader shift in the political-economic environment, which has also seen the rise of Susanne Clark as chamber president and CEO, as well as the rise of a few progressive-left politicians and the emergence of a Biden administration coalition of progressive neoliberals and progressive populists.Footnote 115 In this conjuncture, the US Chamber seeks to steer policy developments in a “business-friendly” direction to ensure that BLM does not become an attack on the “American Free Enterprise System,” as Lewis F. Powell called it in his confidential memorandum almost half a century ago.

The business organizations in this paper engage with BLM and DEI in various ways, but they are united not only by their opposition to racism but also their defense of broader business class interests. While denouncing racism, these organizations oppose the demands of radical BLM activists such as Mary Hooks, who states: “We are going to have to commit to doing things a different way. And you can decide to call it what you want, you can call it socialism, or whatever, but it is about dismantling capitalism and doing the work of living together.”Footnote 116 The overarching goal is to preserve business dominance or at least a business-led compromise; the outcomes to be avoided are an imposed compromise or a business defeat.Footnote 117

Nothing in this article suggests that the emergence of BLM in 2013 was without impact on American businesses; but much evidence suggests that Floyd's murder and the unprecedented protests that followed it was a turning point or critical juncture for American business responses to BLM. Before that point, partisan divides over this issue—Trump's repeated attacks on BLM, and the much lower support for BLM along Republicans had made it difficult, and potentially risky for companies and business organizations to loudly express their support—were they to do so, they ran the risk of alienating customers, provoking boycotts, and so forth. This calculation changed following Floyd's brutal murder when cities across the country were burning or experiencing substantial social unrest. As participants in the National Summit on Equality of Opportunity emphasized, “domestic tranquility” and social stability are important, and its unravelling hastened the arrival of the US Chamber's EOI and related initiatives.

As noted in the preceding text, now that BLM is considered legitimate in parts of the organizational field, business has responded by denouncing racism, but at the same time by advancing a more moderate and reformist policy agenda than the more radical progressive voices in BLM. Here, it is important to distinguish between different factions or strands of activism within BLM. While BLM “cannot be identified with any single leader or small group of leaders”; #BlackLivesMatter “can be picked up and deployed by any interested activists inclined to speak out and act against racial injustice,”Footnote 118 the overall policy orientation of BLM is progressive, interventionist, and redistributive in its orientation.Footnote 119

The US Chamber's EOI shows that America's leading business organization has adopted racially progressive positions. Nevertheless, the legislative agenda of the US Chamber and BLM remains very far apart. The former's response to the challenge posed by BLM is to denounce racism while advocating for moderate and reformist legislation concerning, for example, increased diversity on corporate boards, additional support for minority businesses, and giving formerly incarcerated Americans a second chance. BLM, by contrast, supports public investments that go well beyond the Biden administration's Build Back Better framework and encompass a radical redistribution of wealth. And as we know, the chamber has vigorously and aggressively opposed the Build Back Better legislation.

Here, it may be useful to introduce a conceptual distinction that goes beyond Roemer's distinction between measures to level the playing field by creating more equal starting points, and nondiscrimination that bars racial discrimination when participants compete for positions. In this article I have suggested that many chambers are moving from the latter toward the former. While this constitutes progress, it also has clear limitations, as it will not be sufficient to eliminate inequality. The more radical position, which would be truly transformative, is to reduce inequality between positions in the economy, for example by taxing capital as Piketty has suggestedFootnote 120—and this is opposed by all chambers.

Before concluding this section, I place the EOI relation to different voices and policy orientations within the BLM movement. BLM represents an attempt to challenge and overcome systemic racism in the United States and beyond. But does it necessarily also represent an attack on capitalism and on the American free enterprise system? For Ransby, BLM “inescapably positions itself in opposition to neoliberal racial capitalism.” BLM activists “understand … that racial justice is economic justice and vice versa.”Footnote 121 Despite this assessment and the policy demands listed in the preceding text, whether BLM is inescapably opposed to capitalism without racism is unclear. As was the case in the 1960s and 1970s, there are both moderate, reformist voices—including, it is fair to assume, most (if not all) Black entrepreneurs and businesspeople—well as radical anticapitalist voices and currents within the BLM movement. American business organizations clearly support the former and oppose the latter.

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor represents a strain of thinking that aims to critique not just racism but also racism and capitalism together. Her book documents the struggles of activists in the 1960s who connected Black poverty, institutional racism, and capitalism. She approvingly quotes Black Panther leader Huey P. Newton who stated: “We have two evils to fight, capitalism and racism. We must destroy both racism and capitalism.”Footnote 122 As she explains,

The reality is that as long as capitalism exists, material and ideological pressures push white workers to be racist and all workers to hold each other in general suspicion. But there are moments of struggle when the mutual interests of workers are laid bare, and when the suspicion is finally turned in the other direction—at the plutocrats who live well while the rest of us suffer.Footnote 123

She continues, “[R]acism, capitalism, and class rule have always been tangled together in such a way that it is impossible to imagine one without the other. Can there be Black liberation in the United States as the country is currently constituted? No.”Footnote 124 By contrast, she criticizes elites’ vision for Black liberation, which is limited to “increasing black business subcontracts and … expanding the percentages of blacks in management … and cultural integration into the mainstream of white America—which, of course, is no vision at all.”Footnote 125 The existence of well-to-do Black folks “would vindicate American capitalism.”Footnote 126

To what extent will American business be able to influence, shape, and in effect co-opt BLM in the years to come? Davies reflects: “BLM's lack of clear leadership figures, its flat organizational structure, and its diffuse and mobile centers of activity mean it may prove to be a movement impossible to co-opt. Only time will tell. What we can be certain of, though, is that there will always be some mainstream politicians and institutions that are trying to do just that.”Footnote 127

Discussion and conclusion

The response of American business organizations to BLM and to the challenges of diversity and inclusion is of unquestionable public interest. Mizruchi has lamented America's “ineffectual elite,” which has:

retreated into narrow self-interest, its individual elements increasingly able to get what they want in the form of favors from the state but unable collectively to address any of the problems whose solution is necessary for their own survival…. The American corporate elite has provided leadership in the past. It is long past time for its members to exercise some enlightened self-interest in the present.Footnote 128

With the EOI and its arguments about the benefits for business and American capitalism that can be achieved from overcoming race-related inequalities, the US Chamber of Commerce is providing some leadership and enlightened self-interest. The regional and state-level chambers surveyed in this article are adopting racially progressive positions, often at some cost to themselves, and going beyond what many of their member companies are willing to support.

Many aspects of the US Chamber's EOI represent next generation progressive neoliberalism, or progressive neoliberalism 2.0, which, in addition to helping to address and combat the pathologies of racial bias and racial resentment, aims to steer this emerging agenda in a business-friendly direction. If the US Chamber's aggressive advocacy and the considerable organizational and institutional resources can be used to support “a major overhaul of our cultural ecology,”Footnote 129 then we will make some progress, even if it is largely within the broader ambit of neoliberal capitalism.

It is too early to tell how successful this agenda will be for remedying problems of pervasive racism and racial injustice, as well as the glaring socioeconomic disparities that pervade the United States. Future research would benefit greatly from additional evidence in several areas. Concerning actors’ motivations and intentions, are they cynical, narrowly self-interested, or sincerely committed to advancing the cause of racial equity? Better evidence of the actions taken by business organizations and their member companies, for example regarding the resources committed, would also be beneficial. No less important, we need better data concerning the results on the ground: To what extent do these actions improve socioeconomic outcomes for Black and Brown people as well as the structure and fabric of the American economy and society?

Previous experiences are sobering. As this article has shown, equal opportunity, management training, and financing for minority businesses were already on the agenda of American business organizations including the US Chamber of Commerce during the 1960s and 1970s—but with the benefit of hindsight, it is clear that these initiatives had a very limited impact. Long before BLM, companies have invested billions in diversity structures,Footnote 130 to little effect: “Diversity initiatives have, thus far, failed to improve the numbers of workers of color and white women in measurable numbers, particularly in high-status occupations. Other interventions are necessary to make this change.”Footnote 131 This is why the example of Joplin, Missouri, where the chamber's leader and members of civil society pushed for bold and transformative change, is important. There is almost universal agreement that Floyd's murder prompted chambers and businesses to take more and bolder action than they had up to that point.

While it is essential to recognize how far DEI- and EOI-related initiatives have come, an awareness of their limitations is no less important. The Biden administration's most ambitious Build Back Better proposals had the potential to substantially improve the lives of many people of color—but the US Chamber engaged in aggressive advocacy to weaken and kill this legislation. Will it be possible to retain the existing EDI momentum when the country is in a state of normalcy rather than in an acute crisis? Will companies go beyond talking the talk to walk the walk? Martin Schwartz is skeptical. Schwartz is President of Vehicles for Change (VfC), the largest low-income car ownership program in the country. Over the past two decades, VfC has assisted more than 7,500 families, 90 percent of whom are single mothers and 85 percent are minorities. Schwartz says:

A lot of corporations made these big statements that they were going to invest a ton of money in social equity programs. They made it sound like they were going to do all this stuff. I haven't seen any of it. But what have you done and what is the impact of what you have done? I don't feel like we've made that much progress.Footnote 132

Although many chambers across the country have gotten on the EOI/EDI bandwagon, many have opposed an increase of the minimum wage, which is of vital importance to working people of all races and ethnicities. As valuable as EOI/EDI initiatives are, it seems unlikely that they will transform the deep structural inequalities of power and wealthFootnote 133 that pervade contemporary capitalism.

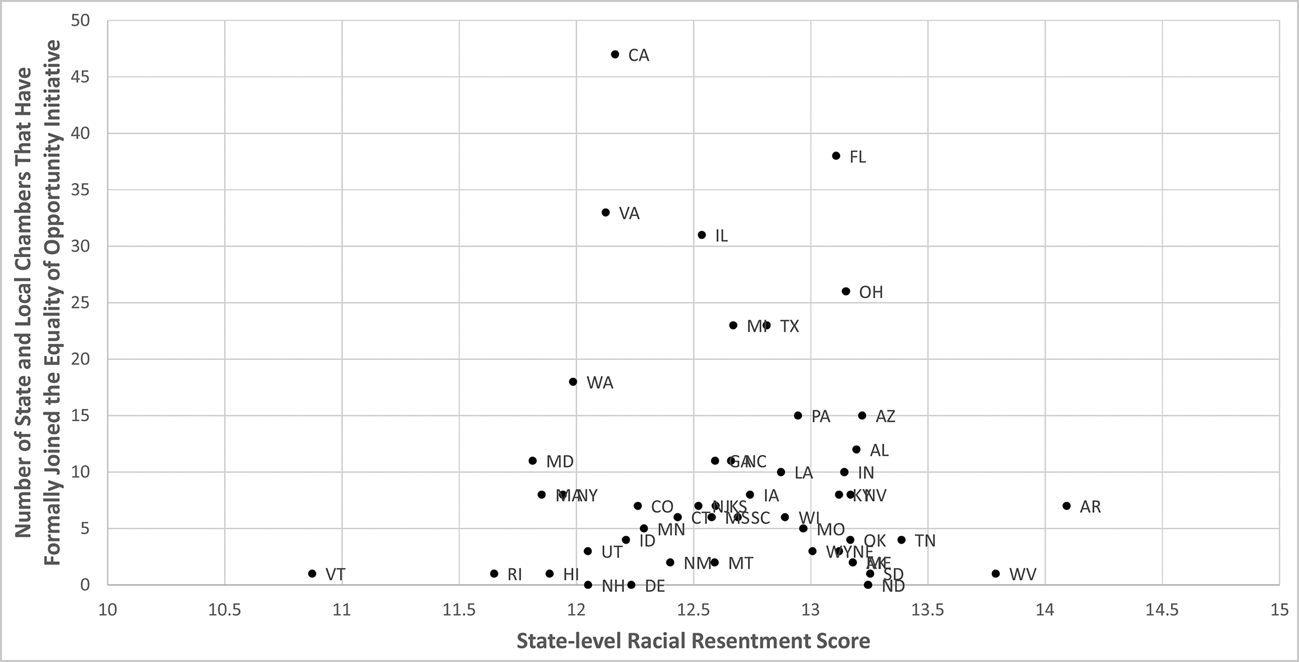

Future research should also pay closer attention to geography. Figure 7 plots the relationship between the state-level racial resentment scores and the number of chambers in each state that have joined the EOI as partners. To combat racial resentment, it would be beneficial if there is a positive association between the number of chambers engaging in EOI and racial resentment so that EOI-related activities are more prevalent and widespread in states with higher racial resentment scores.

Figure 7. The relationship between the state-level racial resentment scores and the number of chambers in each state that have joined the EOI as partners.

Instead, we find a slight negative association between the number of chambers engaged in EOI-related activities and state-level racial resentment scores. On average, states with higher levels of racial resentment have fewer chamber engaging in EOI-related activities than states with lower levels of racial resentment. This suggests an additional limitation of current approaches. Furthermore, have chambers been willing to take a stance against voter suppression legislation in Georgia, Texas, and other states? It seems not.

In conclusion, there are many unanswered questions. Hacker and Pierson have stressed the “need to encourage moderate elements of the business community to go to bat for the mixed economy.”Footnote 134 Is the US Chamber's EOI a signal that American business organizations have become more open to a mixed economy? If the progressive neoliberalism 2.0 agenda is successful, America's dominant class can breathe a sigh of relief because this program does not fundamentally threaten their material interests. Even so, a country in which all people including African Americans have a real shot at living their own American Dream would be a genuine step forward. The leadership provided by some chambers provides grounds for cautious optimism. It is hard to disagree with Schwartz: “We have a tremendous amount of work to do.”Footnote 135 One thing is certain: More research is needed on American business responses to BLM.

Acknowledgements