Introduction

The 2007 global financial crisis substantially changed the nature of the relationship between financial industry firms and society. A stream of corporate scandals and the collapse, or nationalization of large firms in the wake of the crisis (e.g., Bears Sterns, Northern Rock, and Lehman Brothers in the United States, as well as ABN-AMRO and Royal Bank of Scotland in Europe), seriously tarnished the public image of the financial services industry. Investment banks, insurance providers, and hedge fund managers, largely held responsible for the crisis, especially in the context of regulatory failure,Footnote 1 found themselves scrambling to rebuild their public image and restore a modicum of trust within society at large.

This article examines the impact of the financial crisis on one aspect of these efforts: namely Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).Footnote 2 Firms’ CSR commitments and disclosures not only came under the spotlight during the crisis, revealing weaknesses in structures of corporate governance, but were also seen as a panacea for ameliorating the financial impact of the crisis.Footnote 3 Perhaps not surprisingly, our question has already attracted considerable scholarly attention.Footnote 4 For many scholars, a chief concern has been the extent to which the financial crisis has negatively impacted firms’ CSR commitments. They argue that CSR commitments are costly and, despite providing potential long-term net financial benefits, are an easy way to save money in times of economic uncertainty.Footnote 5 In short, in order to survive in times of crisis, firms are often incentivized to focus on the “vital” aspects of business and are therefore expected to put CSR commitments on hold.

Our analysis examines this perspective, focusing on the assumptions linking a firm's immediate economic and financial context to their CSR commitments. Building on recent insights regarding the institutional determinants of CSR,Footnote 6 we argue that this line of thinking is too “agent-centric”: It assumes that firms single-handedly determine their CSR commitments outside of the external constraints of their respective fields of economic governance and modes of market and state regulation. Current institutional approaches to CSR elaborate on how the broader social environment within which firms operate shape and influence a firm's decision to engage in and disclose CSR commitments. For example, how varieties of capitalism,Footnote 7 different business and regulatory systems,Footnote 8 and structures of corporate governanceFootnote 9 shape firms’ CSR commitments.

A less developed but important insight of this literatureFootnote 10 relates to firms’ “visibility.” Firms that are more visible to the public and that receive more public scrutiny tend to experience more pressure to make and disclose information on their CSR commitments. In fact, effectively communicating details about CSR commitments through formal disclosure procedures becomes a way for firms to shape their public image and claw back public trust.Footnote 11 Our central purpose in this article is to further develop these insights and engage in more explicit theorizing about how visibility and public scrutiny act as additional institutional constraints, and offer opportunities, on how firms disclose information on CSR commitments, especially in the context of economic hardship. First, we contend that financial volatility leads firms to engage in more comprehensive and extensive reporting of their CSR commitments. Our argument is that crises have their own “demonstration effects,” increasing firms’ visibility. Crises work to highlight the dubious activities of CEOs, investment managers, and other industry actors and can expose industry efforts to avoid more stringent regulation in the post-crisis period. Second, we examine how attention in the news media can increase a firms’ visibility, thereby increasing public scrutiny and challenging a firm's stock of public trust as well as its public image. Our contention is that intense news media attention drives firms to increase reporting on CSR commitments.

We test our argument using a unique dataset comprising information on CSR disclosures for over 170 European firms operating in financial services and other sectors for the financial crisis period (2007 to 2012).Footnote 12 Importantly, our dataset allows us to compare finance to other sectors and, hence, to control for sector-specific differences.Footnote 13 Our focus on the financial sector in Europe during the financial crisis also constitutes a type of “least likely case” for our argument. A financial crisis is an extreme form of economic downturn and the assumption we seek to challenge is that firms facing economic hardship will be incentivized to jettison their CSR commitments. Finding evidence that this assumption does not hold during this time of extreme economic hardship, stress, and volatility should imply greater generalizability for our theory.

Controlling for a number of alternative explanations, our statistical analysis produces several key findings. First, we find robust evidence showing that firms tend to engage in more comprehensive CSR reporting during times of extreme financial volatility. This finding challenges the assumption that firms invariably decrease their CSR engagements during times of economic hardship. Second, we find that firms’ CSR reporting is positively correlated with increased public scrutiny. Faced with mounting public pressure, firms tend to engage in more extensive reporting. Our findings therefore support research linking CSR engagement and CSR disclosure to how firms manage their public image and shape their reputation.Footnote 14 Third, we find that firms operating in the financial services industry are not uniquely susceptible to these effects. In fact, our findings show that finance is slightly more resistant to the impact of public scrutiny than firms operating in other sectors. Though financial firms do tend to respond to public scrutiny by more extensive CSR reporting, this effect is not proportional to the extreme levels of public scrutiny they faced during the height of the financial crisis.

Economic hardship, crises, and CSR

Many scholars predict a distinctly negative relationship between periods of crisis and CSR. The underlying logic is derived from a broader literature linking CSR to a firm's financial performance and its short-term financial concerns.Footnote 15 Though ramped up CSR can improve a firm's bottom line,Footnote 16 this does not hold during times of financial crises, economic downturns, or general market volatility, which create uncertain business environments. The central assumption is that firms, seeking to maximize profits and shareholder value, only engage in CSR when it is financially feasible. A harsh economic climate or sharp economic downturn puts pressure on firms’ so-called “non-vital activities.”Footnote 17 Hence, when resources are tight, firms are forced to cut back expenses and are incentivized to jettison CSR commitments.

The same insights have been applied to understanding CSR commitments during the global financial crisis of 2007. Within this uncertain business climateFootnote 18 firms were less liquid and therefore harder pressed to justify a continued stream of resources to CSR. “The most important negative impact of CSR to companies is the potential cost for the implementation of CSR initiatives,”Footnote 19 and this is only exacerbated during times of crisis. Firms try to “avoid the negative effects of crises by remedial actions: such as cutting costs by laying off workers, postponing investments, reducing budgets for the following year in a contraction manner, consuming less.”Footnote 20 For Njoroge (Reference Njoroge2009), CSR initiatives can be delayed, or cancelled, because of a financial crisis. Fernadez-Feijoo Souto (Reference Fernadez-Feijoo Souto2009, 43) argues that the stakes are even higher: “CSR in periods of crisis is a threat to firms’ survival.” Empirical tests seem to bear out these assumptions. Most notably, Karaibrahimoglu's (Reference Karaibrahimoglu2010) content analysis of annual non-financial reports shows that companies decreased their reporting of CSR projects in response to the financial downturn.

Recent advances in the broader CSR literature, however, challenge this assumption about the negative link between economic hardship and CSR commitments. Scholars drawing on insights from theories of institutionalism have highlighted the extent to which CSR decisions are not made in a complete vacuum nor are they wholly within “the realm of voluntary action.”Footnote 21 Instead, CSR is also shaped by factors beyond the control of firms and located in the institutional context within which they operate.Footnote 22 Institutionalism, in other words, challenges the agent-centric perspective of the determinants of CSR commitments that has largely been adopted by management studies.Footnote 23 Jacob (Reference Jacob2012) shows in a case-study that CSR can positively affect a company's reputational value, and firms, therefore, will increase CSR on topics that primary stakeholders deem important. For our purposes, institutionalism questions the extent to which firms are free to jettison CSR commitments during times of economic hardship.

Scholars have adopted an institutional approach to CSR by variously examining firms’ general business environment or “broader social context.”Footnote 24 Scholars point out important differences within CSR commitments as they relate to state and market regulations, systems of corporate governance, and institutionalized norms of appropriate corporate behavior, as well as states’ capacity to monitor firms’ activities.Footnote 25 One prominent approach applies insights from the “Varieties of Capitalism” literature to studies of CSR. From this perspective, firms operating under the conditions of a liberal market economy (LME) tend to adopt more “explicit” forms of CSR to compensate for the missing institutionalized arrangements characteristic of coordinated market economies (CME).Footnote 26

Similarly, scholars have highlighted the fact that CSR is shaped by important sector-level differences. On one level, CSR operates through a kind of “corporate peer pressure” where firms operating in a specific industry implement, monitor, and enforce “regulatory mechanisms to ensure fair practices, product quality, workplace safety.”Footnote 27 On another level, firms operating in the same sector tend to face “similar challenges” and, by extension, similar “CSR patterns and regulations are likely to develop, affecting CSR standards and forcing CSR policies implemented by firms in those industries to converge.”Footnote 28 As demonstrated in Jackson and Apostolakou (Reference Jackson and Apostolakou2010), so-called high impact sectors, such as extractive industries, automobile manufacturing, and chemicals manufacturing, face unique challenges and risks related to the environment, consumer protection, and the economy, and hence, are more likely to make CSR commitments to offset these risks. Sector-specific institutional differences are not confined to the state and can instead be transnational, impacting firms across any number of countries and producing isomorphism among firms operating in similar sectors.Footnote 29 These pressures are particularly salient for multinational corporations. As scholars working in the field of international business studies point out, multinational corporations have to contend with different and often competing host-state institutions that can inform their CSR commitments.Footnote 30

Finally, scholars emphasize how a firm's visibility, and hence, related scrutiny by the public and the news media, affects its CSR decisions. First, visibility tends to vary by industry: Firms operating in so-called “high-impact” industries (like extractive industries) compared to “low-impact” industries (like consumer services) are simply more visible.Footnote 31 At the same time, firm visibility can be exploited by a number of external stakeholders. Environmental NGOs, consumer protection groups, and regulators, for instance, can increase public pressure on firms to implement or keep their CSR commitments.Footnote 32 Equally, the news media monitors firms’ behavior and calls attention to socially irresponsible activities, making it more likely that companies will engage in CSR.Footnote 33 Finally, firms can also be directly targeted by consumer boycotts and, thereby, face considerable reputational risks. An emerging line of scholarship marries insights from social movements theory and organizational theory and shows how firms targeted by consumer boycotts use CSR commitments and disclosures to actively reshape their public image and bolster their reputation.Footnote 34

Firm visibility, financial crises, and public scrutiny

A central purpose of this article is to contribute to these recent advances in institutional approaches to CSR. We do so by further developing insights about firm visibility and public scrutiny and examining how these factors shape CSR commitments. To this end, and in what follows, we examine firm visibility in terms of two main factors: financial crises and public scrutiny.

First, financial crises do not only affect a firm's bottom line. Instead, crises have “demonstration effects”Footnote 35 that link a firm's behavior to the causes of the crisis and can work to negatively impact a firm's level of public trust. Periods of extreme financial volatility expose the negative externalities of financial sector involvement in regulatory issues. Excessive financial sector influence over financial regulations increases during periods of financial boom when private-sector actors find themselves relatively unopposed by countervailing interests.Footnote 36 Large-scale events like financial crises, however, can magnify financial fluctuations and shine a light on weak regulations.

As financial markets become increasingly stressed and more volatile, regulators are more prone to re-regulate specific industries, and industry actors can find it difficult to justify the furtherance of self-regulation and their close involvement in regulatory decision-making processes. Faced with the possibility of more stringent regulation imposed from a regulatory agency, many firms opt to impose more stringent self-regulations themselves.Footnote 37 As Moon (Reference Moon, Habisch, Jonker, Wegner and Schmidpeter2005) argues, firms tend to engage in (transparent) CSR to anticipate the threat of stricter national or supranational regulation.Footnote 38 Additionally, in the wake of the crisis, firms experience a decline in legitimacy, i.e., the social acceptance of firms and their activities.Footnote 39 Faced with higher public criticism, firms find themselves fighting to regain their social license to operate, or, in other words, their public consent.Footnote 40 To gain or secure legitimacy from main stakeholders, and to manage reputational risks, companies will report more on sustainability, particularly on issues of governance and environmental policies.Footnote 41 Crises implicate firms in economic downturns, undermining a firm's position in society, diminishing trust, and ultimately harming the value of a firm's brand. Restoring public trust and rebuilding a brand is dependent upon the provision of publicly available information on firms’ social and environmental responsibilities.Footnote 42 CSR reporting is therefore a way for firms to effectively communicate information about their CSR commitments.Footnote 43 These insights lead to our first hypothesis.

H1: Financial Volatility: the greater the levels of financial volatility, the more firms will engage in extensive reporting of their CSR commitments.

News media attention can also function to increase firms’ visibility and, subsequently, increase pressure to engage in and report CSR commitments. The news media can subject firms to the threat of public exposure, functioning as a watchdog that informs the public about corporate activities and hence, poses a threat of public exposure.Footnote 44 Along with NGOs and consumer protection groups, the news media acts as an additional “external stakeholder” monitoring and reporting on corporate (mis)behavior.Footnote 45 The media can be critical in mobilizing social movements, which is particularly noticeable within the environmental sphere.Footnote 46 A study by Schreck and Raithel (Reference Schreck and Raithel2018) finds that visibility, which they operationalize as media coverage, has a significant, positive effect on the CSR disclosure. They conclude that firms use sustainability reports to respond to external pressure since high levels of visibility lead to more legitimacy pressures.

Furthermore, the news media can enhance the salience of regulatory issues, increase the public scrutiny of particular firms and particular industries, and name and shame firms by further implicating them in an economic downturn, or by highlighting socially irresponsible activities (or even jettisoning such activities). Public scrutiny causes firms to be more sensitive to social and political stakeholders and therefore drives the willingness to engage in sustainability.Footnote 47 For Culpepper (Reference Culpepper2011), the critical difference is between so-called “quiet politics” and “loud politics.” During periods of quiet politics, when there is little media attention and issues remain less salient, firms can fly under the radar of public attention. However, focusing events and increased media attention can magnify issue salience turning quiet politics loud. Under these conditions of extreme media scrutiny, firms may find themselves constrained in their ability to carry any number of functions, including attempts to decrease or diminish their CSR commitments. These insights lead to a second hypothesis.

H2: Public Scrutiny: the higher the levels of media attention, the more firms will engage in extensive reporting of their CSR commitments.

Finally, we make a comparison between financial services corporations and firms operating in other sectors (e.g., manufacturing, telecommunications, retail, etc.). As such, we build on insights that CSR has important sector-specific differences,Footnote 48 many of which are transnational in character and can lead to a type of isomorphism of CSR commitments within specific sectors of activity. For this study, the unique role of financial service providers (banks, insurers, fund managers, etc.) in the financial crisis should impact their decisions to report more extensively on their CSR commitments. After all, financial services firms were deeply implicated in the financial crisis, especially in terms of weakening the financial regulatory architecture at the national, EU, and international levels.Footnote 49 In fact, many scholars have indicated that the crisis was at least partly the result of regulatory capture: a situation where financial services firms were determining the content of financial regulation themselves.Footnote 50 Finally, financial services firms not only faced conditions of extreme financial volatility during the crisis, in some instances leading to their collapse or (re-)nationalization, but were also subject to considerable naming and shaming practices in the news media. This leads to our third hypothesis.

H3: Financial Sector: during times of financial volatility and increased public scrutiny, financial services firms will engage in more extensive CSR reporting than firms operating in other sectors.

Research design

The aim of this article is to examine the effects of the financial crisis on European firms’ CSR reporting. Our focus on European firms acknowledges that the financial crisis was a variegated phenomenon that took on different shapes and had different impacts in different parts of the world. In other words, despite being interconnected, it would be misleading to conflate the U.S. sub-prime mortgage crisis with the European sovereign debt crisis. Our focus on Europe therefore allows us to control for some of these differences. In Europe, the crisis played out primarily as a sovereign debt crisis with several EU member state governments being unable to pay down national debt or to bailout highly indebted banks. The mechanisms of the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), which is tasked with controlling inflation, limited governments’ ability to react to the crisis. Indeed, the fact that all the firms considered in this analysis are also part of the European Union further justifies our focus on EU firms.

The remainder of this section explains how we have operationalized our four hypotheses, as well as various control variables, and provides details on data collection and data reliability. Descriptive statistics for all indicators used in this analysis can be found in the online appendix.

CSR reporting

We measure CSR using the GRI database.Footnote 51 GRI maps out principles and detailed indicators for reporting on every aspect of CSR performance, combining economic and environmental indicators with social performance.Footnote 52 Empirical studies comparing GRI to similar databases, such as the Dow Jones Sustainability Index and the KMPG International Survey of CSR Reporting, show its superior reliability and coverage,Footnote 53 something that is reflected in its widespread use by firms in the European Union and in countries of the OECD.Footnote 54

The GRI database consists of CSR reports and evaluations for individual firms per year. Importantly, GRI data comprises information on CSR disclosures and therefore not actual CSR activities or outcomes. We justify the use of disclosure data in two ways. First, our theoretical framework focuses on the reputation-building activities of firms facing economic hardship. Indeed, through CSR reporting, companies are able to showcase their CSR commitments; they illustrate that their operations are consistent with social expectations and norms.Footnote 55 A company's CSR reporting is a tool for companies to communicate their CSR activities to external parties. Second, recent research suggests that the credibility of CSR reporting is dependent on whether companies adhere to leading reporting standards like the GRI. These standards function both as a means for companies to formulate their CSR strategies and for stakeholders to subsequently evaluate them.Footnote 56 Therefore, reporting on CSR and actual CSR activities are strongly correlated.Footnote 57

The data used in this analysis is limited to EU firms, and includes firms form Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, the United Kingdom, Hungary, Italy, Sweden, Germany, Spain, France, Greece, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Ireland, for the period 2007–12. An important contribution of this analysis is how nuanced changes to financial volatility and public scrutiny impact CSR reporting. As such, we only include firms committed to yearly CSR reporting (i.e., firms that are missing reports for certain years are excluded). Our data therefore comprises 151 individual firms and 734 CSR reports for the six years of this study. A complete list of firms used in this study, as well as a breakdown of firms by country, can be found in the online appendix.

The GRI index scores firms’ CSR reporting on a six-point scale that ranges from C to A+, capturing variation in the extensiveness of a firm's reporting. High scores, like “A+,” are given to reporting practices that provide extensive detail on a very large number of CSR commitments including an inclusive range of performance indicators covering “economic,” “environmental,” “labor practices and decent work,” “human rights,” “society,” and “product responsibility” categories. Low scores like “C” are given to reports that give only very basic details. In the timeframe of our research, firms used the GRI 3.0 standard for reporting.Footnote 58 Firms can choose to assess their own reports (level C, B, or A) against the criteria of the GRI Application Level or to either have a third party offer a second opinion or request a GRI check, resulting in a “plus” (+) added to the application level afterwards. For the purposes of this analysis, we only use third-party checked and GRI checked reports, and hence, we recoded the ranking system on an ordinal scale ranging from 1 (C), 2 (B), and 3 (A). The higher a firm's scores, the more extensive the CSR reporting is.

Financial volatility

We measure financial volatility using data derived from the European Central Bank's Composite Indicator of Systemic Stress (CISS).Footnote 59 CISS measures the current state of instability in European financial markets, bringing together data on five segments of the financial system: the sector of banks and non-bank financial intermediaries, money markets, securities markets, as well as foreign exchange markets. Yearly data on financial stress in each country were calculated from monthly values and are appropriate for the data on firms’ GRI scores, which are measured annually. Financial volatility values range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating greater levels of volatility. Determining each firm's home country allowed us to link data on national financial volatility to firms’ GRI scores. CISS data present an ex post measure of systemic risk.Footnote 60 As such, and in order to mitigate issues of endogeneity, financial stress values for the year preceding the GRI reports were used in the regression analyses. This approach to measuring the effects of the financial crisis on GRI marks an important advance on existing studies. Existing studies treat the financial crisis as a single, monolithic event that does not vary over time nor across countries. Indeed, most existing scholarship operationalizes the crisis using a binary indicator distinguishing simply between the pre-crisis and post-crisis periods.Footnote 61 CISS data allows us to examine correlations between volatility and CSR reporting in each of the six years of our data set, as well as to capture important fluctuations in volatility in different countries in different years.

We argue that CISS data provides a fine grained and compelling measurement of financial volatility. It is important to note that scholars have long used more general macro-economic indicators to control for economic hardship in studies of CSR. As noted above, existing research suggests that the decision to report on CSR commitments is also related to a firm's immediate economic environment. That is, firms will be less likely to engage in and report CSR if operating in “relatively unhealthy economics environments where the possibility of near-term profitability is limited.”Footnote 62 Research measures the relative economic health that firms’ encounter in terms of inflation and weak business and consumer confidence. As expected, there are problems of multicollinearity if we were to include these indicators along with our CISS data in our regression models. As such, we have performed a series of robustness tests and present the results below. The data, all drawn from World Development Indicators include Inflation (higher scores = higher inflation), Business Confidence (higher scores = greater confidence), and Consumer Confidence (higher scores = greater confidence).

Public scrutiny

Public scrutiny is measured as the amount of news media coverage of each individual firm in our dataset for the entire period of the study and measured on a yearly basis. To this end, and using the online database Factiva, we searched for all mentions of each individual firm in our dataset by name (either full name or full name and acronym) for each year of our study.Footnote 63 We did this in two ways. First, we coded for all mentions in all the national newspapers in a firm's home country. This provided our measurement of national public scrutiny. Second, we coded for all mentions in all newspapers that are not in a firm's home country. This gave us our measurement of international public scrutiny. Examining national and international scrutiny separately gives us insight into the unique transnational pressures that firms may face relative to the pressures that they may face at home. However, examining the data shows a very high level of correlation between our two measures of public scrutiny.Footnote 64 Therefore we opted to use a third indictor, public scrutiny, which combines national and international public scrutiny. Public scrutiny was log-transformed to normalize distribution.

Comparing the financial services sector to other sectors

Part of our goal in this analysis is to compare the effects of the financial crisis on CSR reporting in finance to firms in other sectors of economic activity. To this end, and using data from the GRI dataset, we have coded all 170 firms in our dataset in terms of their main economic sector of activity, making a key distinction between financial industry firms (including banks, insurance providers, and securities firms) and firms from all other sectors. Overall, there are thirty-two different economic sectors in our data. A full breakdown by sector is available in the online appendix.

Control variables

In addition to operationalizing our hypotheses, we also included several control variables in our analysis. These are largely derived from the broader institutional CSR literature.

First, a central insight in extant studies is that large firms tend to engage in more CSR than smaller firms.Footnote 65 Large firms are both more visible to the public than smaller firms and their superior resources make CSR easier to implement. Firm size is operationalized using GRI data indicating whether firms in our dataset are (1) small firms, (2) large firms, or (3) multinational firms. A small firm has a headcount under fifty and a turnover and balance sheet under ten million a year. If a firm exceeds these numbers, it is considered a large firm. Multinational firms, on the other hand, are defined as firms that produce goods or deliver services in more than one country.

Second, scholars have pointed out that firms’ decisions regarding CSR commitments might be motivated by inter-sector competition. Firms engage in less CSR when there is either too much or too little inter-sector competition. Too much competition means that a firm's profit margins are narrow and that these firms will not want to spend money on CSR. Too little competition, and firms will have little incentive to use CSR to enhance their “competitive advantage.”Footnote 66 We measure competition by combining two different scores using data from the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI): namely, “domestic competition” and “foreign competition.” The resulting index, Competition, has values ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 = very low competition and 5 = very high competition.

Third, firms’ CSR engagements increase if there are strong and well-enforced state regulations in place to ensure such behavior. Robust legal systems, which effectively protect outside investors, reduce the incentives for insiders to act in irresponsible ways, such as engaging in the manipulation or obfuscation of a firm's earnings to conceal their own rent-seeking behavior.Footnote 67 We use data on countries’ legal systems from the World Justice Projects Rule of Law index (2012). Year-level data includes values that range from 0 (no legal enforcement) to 1 (perfect legal enforcement).

Fourth, we control for varieties of capitalism and for sectoral impact. Firms operating in LMEs face different and more explicit and pronounced pressures to carry out CSR commitments than firm in CMEs.Footnote 68 Following data presented in Jackson and Apostolakou (Reference Jackson and Apostolakou2010, 379), we created a dummy variable distinguishing between LMEs and CMEs. LMEs (coded as 1) include the United Kingdom and Ireland. CMEs (coded as 0) include Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, Italy, Sweden, Germany, Spain, France, Greece, the Netherlands, and Portugal. Additionally, we introduce a dummy variable for high impact versus medium-low impact industries. Again, we use data from Jackson and Apostolakou (Reference Jackson and Apostolakou2010, 379). High impact sectors (coded as 1) include automobiles, basic resources, chemicals, construction and materials, food and beverage, oil and utilities, retail, and utilities. Medium-low impact sectors (coded as 0) include banks, consumer goods, consumer services, financials, insurance, media, technology, telecommunications, and travel and leisure.

Fifth, scholars have pointed out a link between CSR and the business education environment. CSR reporting will be more extensive if firms “operate in an environment where normative calls for such behavior are institutionalized, for example, in important business publications, business school curricula, and other educational venues in which corporate managers participate.”Footnote 69 The education environment can pose a normative pressure on firms by setting standards for legitimate organization practices.Footnote 70 We measure business education environment using GCI data on the quality of management schools. Values range from 1 = worst, to 7 = best.

Finally, CSR might be a function of employer-employee relations. The thinking is that CSR reporting is more extensive if firms “belong to trade and employers’ associations, but only if these associations are organized in ways that promote socially responsible behavior.”Footnote 71 CSR reporting tends to be more extensive when firms engage in institutionalized dialogues with unions, employees, community groups, investors, and other stakeholders. To measure these relations, we again use GCI data on labor-employer relations. Scores range from 1 = very poor relations, to 7 = very good relations.

Analysis and findings

To test the relative explanatory power of our hypotheses, we estimate a series of multi-level regression analyses with random intercepts at two levels: year and country. As CSR reporting takes on three ordered values, we estimate the models using ordered logistic regression. A test for multicollinearity among our independent variables revealed problems of high correlation between three control variables: competition index, legal system, and labor-employer relations.Footnote 72 We therefore test legal system and labor-employer relations in separate regression models treating the results as a robustness test for our analyses.

Our main regression results are presented table 1 in four different models. Model 1 is a “baseline” model where we only include our control variables. Models 2 and 3 test H1 and H2 respectively. Model 4 includes all our variables. H3, predicting differences related to firms engaged in financial service provision, is examined in each model via the control variable financial services industry where the reference category is non-financial industry firms.

Table 1: Multi-level Ordinal Logistic Regression Analysis of the Determinants of CSR Reporting

Notes: Odds ratios with t statistics in parentheses. Number of Countries = 15; Number of Year-groups = 90.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

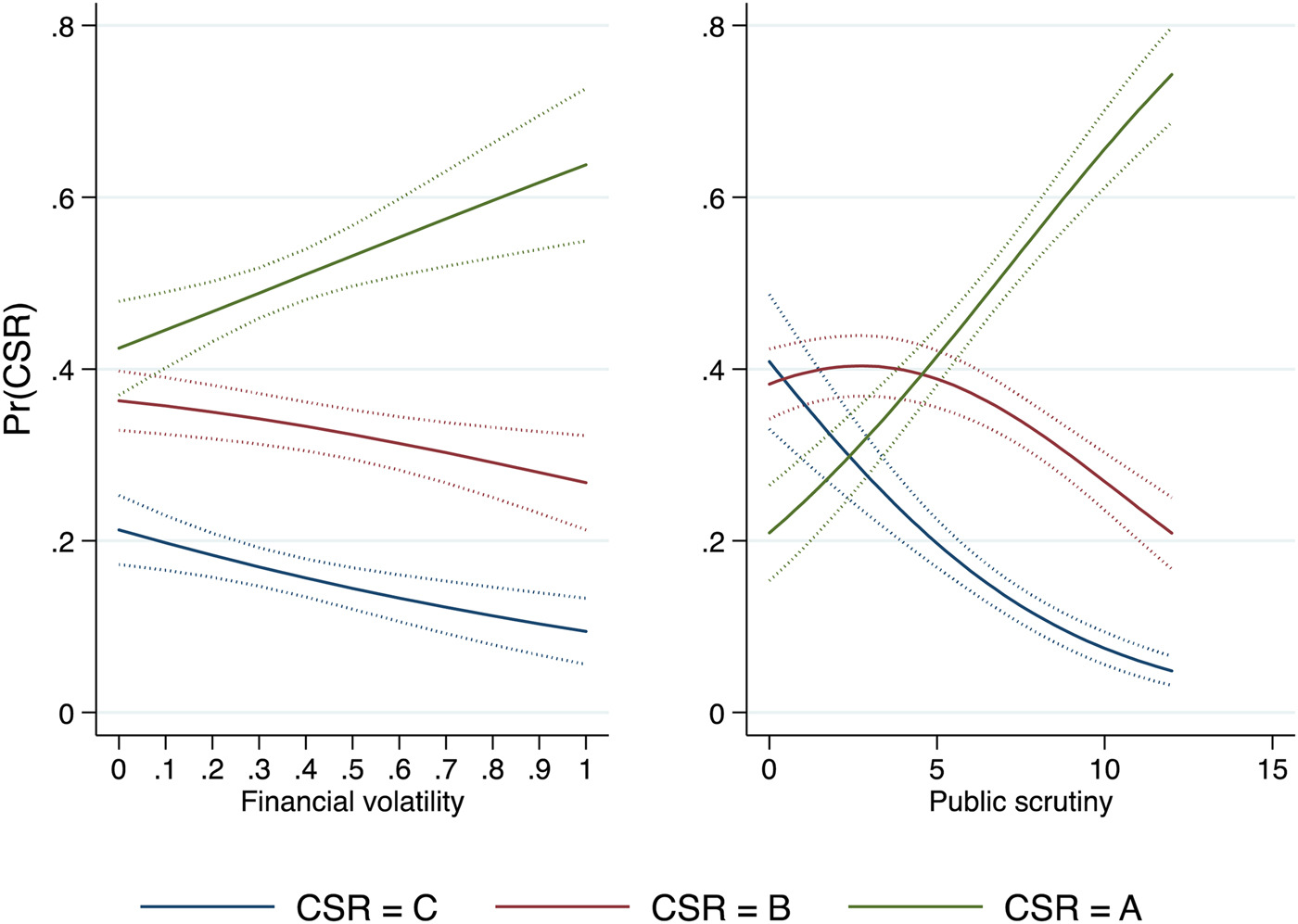

The results in table 1 provide strong support for H1, predicting a positive correlation between high levels of financial volatility and more extensive CSR reporting. Specifically, as we can see in model 2, with each additional increase in financial volatility the odds of more extensive CSR reporting are about 4.4 greater. Marginal effects, presented in figure 1, help interpret these results. In the left-hand figure, we can see that the probability of firms receiving a high CSR reporting score (A) increases from about 40 percent to nearly 70 percent as financial volatility moves from 0 (very stable) to 1 (very volatile). At the same time, the probability of having lower CSR reporting scores (B and C) decreases as financial volatility increases. Our findings clearly challenge existing studies predicting a negative correlation between economic hardship and financial crisis and firms’ CSR reporting. Importantly, this positive correlation suggests that the link between financial crisis and CSR reporting is not wholly structured by a firm's bottom line. Even though CSR might be costly and an easy thing to jettison during uncertain and economically challenging times, the fact that extensive CSR reporting increases as the crisis deepens reflects our argument that firms understand the importance of rebuilding public trust especially during trying times.

Figure 1. Marginal effects of financial volatility and public scrutiny on CSR Reporting

Regression results also support H2. Specifically, there appears to be a strong positive correlation between public scrutiny and more extensive CSR reporting. The news media appear to play a crucial role in bringing firms to the attention of the public and, in turn, pressuring firms to report more extensively on their CSR commitments. As presented in model 3, we see that each additional news media “mention” increases the odds of more extensive CSR reporting by a factor of about 1.3. The marginal effect of public scrutiny on CSR reporting are also telling. The right-hand figure in figure 1 shows a marked upswing in the probability of firms having higher CSR reporting scores as public scrutiny increases, moving from a 20 percent probability to about an 80 percent probability. As expected, the probability of having lower CSR scores decreases as public scrutiny increases. Firms facing intense news media coverage appear to engage in more extensive CSR reporting.

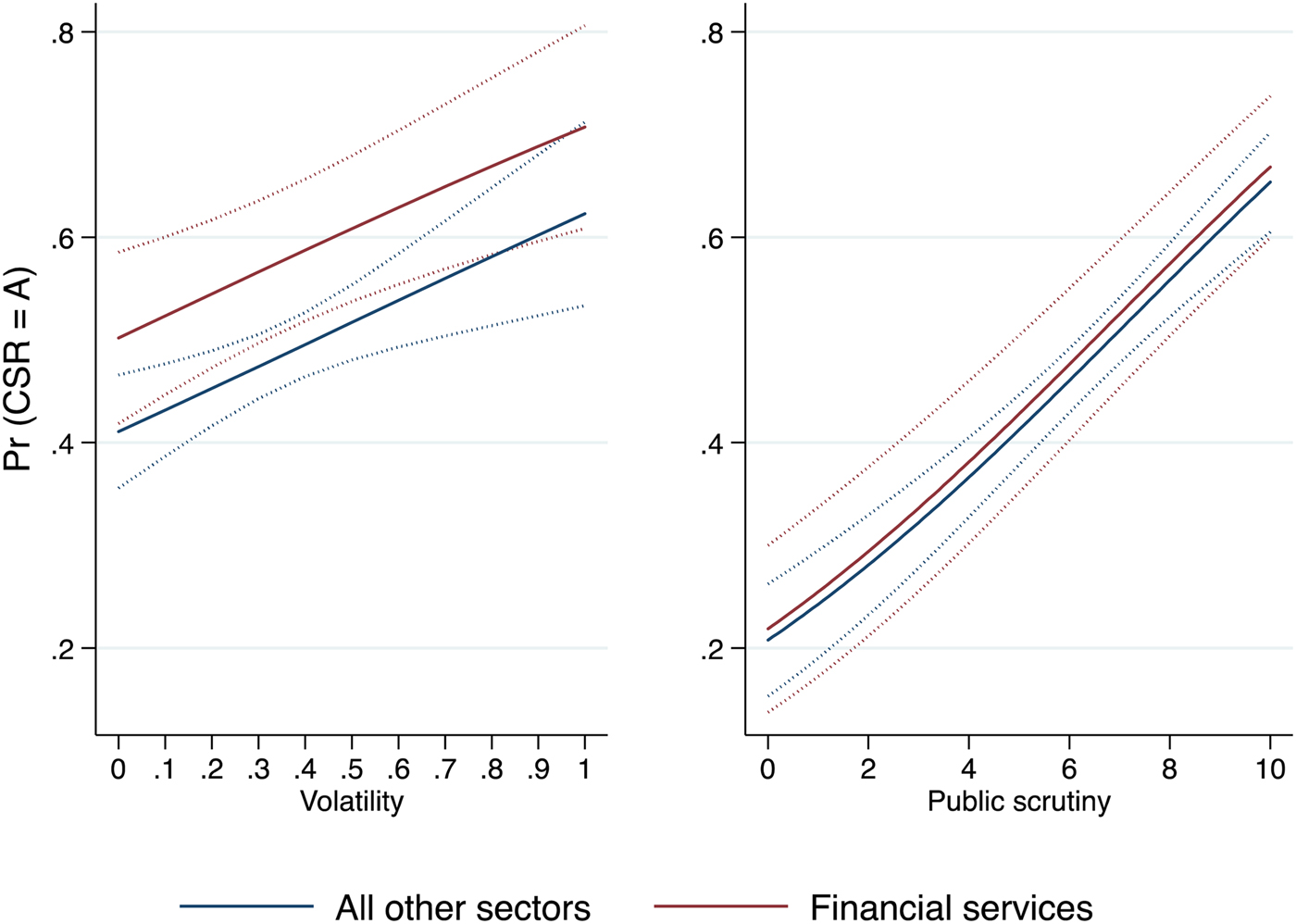

The results for H3, examining potential sector-specific differences related to firms operating in the financial services industry, are mixed. The results are either not significant (as in models 1 and 2) or significant but negatively correlated with CSR reporting (as in models 3 and 4). While this finding may appear to contradict our expectations in H3, we need to be careful in interpreting the results as they are likely sensitive to differences in the specifications in our various models. Indeed, examining marginal effects for financial volatility and public scrutiny can shed some light on these differences between finance and firms in other sectors. Figure 2, plotting the marginal effects for financial volatility and public scrutiny on CSR reporting (based on the results in models 2 and 3, respectively) show that there are actually few differences between financial service providers and firms in other sectors. In both cases, we can see that the likelihood of firms receiving a high CSR reporting score increases dramatically as financial volatility and public scrutiny increase. While financial service providers have slightly higher values than firms in other sectors, these differences are non-significant given overlap in confidence intervals.

Figure 2. Effects of financial volatility and public scrutiny on CSR reporting

While it seems that there are only negligible differences between financial firms and firms in all other sectors, there are nevertheless large differences in actual news media coverage. In fact, our data shows that public scrutiny disproportionately targets finance, at least in the period covered in this analysis. Indeed, from 2007 to 2012 firms operating outside of finance received about 4,300 news media mentions per year. By contrast, finance, in the same period, has anywhere from 12,000 mentions in 2007 to nearly 30,000 mentions in 2012. While public scrutiny may drive firms to increase extensive CSR reporting, the impact of public scrutiny on CSR reporting is not incremental, where each additional news media mention leads to proportionate increases in CSR. Turning quiet politics loud is not a function of the raw amount of news media mentions. Instead, the process appears to require a certain threshold of increased news media attention and additional mentions above this do not add significantly to how public scrutiny affects CSR reporting. Financial sector firms are perhaps slightly less sensitive to news media attention, but they are certainly not impervious to its effects.

Robustness tests

We provide two tests for the robustness of our results to assess the sensitivity of our models to alternative specifications. Results are presented in table 2.

Table 2: Multi-level Ordinal Logistic Regression Analysis of the Determinants of CSR Reporting

Notes: Odds ratios with t statistics in parentheses. Number of Countries = 15; Number of Year-groups 90.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

The first test is related to our main finding, namely that financial volatility drives firms to increase, rather than decrease, the extensiveness of their CSR reporting. It is important to provide a robustness test for this finding given the extent to which it challenges existing scholarship. To this end, models 1, 2, and 3 examine the determinants of CSR using alternative measures for financial volatility mentioned above, namely inflation, consumer confidence, and business confidence. Results for inflation and consumer confidence show no significant differences in the models, while business confidence shows a negative correlation with CSR. In other words, as business confidence decreases, firms engage in more extensive reporting of their CSR commitments. These results provide more support for our main finding and suggest that our financial volatility indicator is not driving the results in a particular direction.

One other remaining challenge to our findings is that our results are unique to the European Union and/or the European sovereign debt crisis. European firms traditionally engage in “implicit” forms of CSRFootnote 73 and their response to the financial crisis may have resulted in exaggerated forms of “explicit” CSR (leaving implicit CSR structures unchanged). However, our analysis includes an important distinction between LMEs, where scholars have identified that explicit forms of CSR are most prevalent, and CMEs, where we tend to see implicit CSR. The results in tables 1 and 2 suggest that our dummy LME indicator shows no significant differences in any of the models and hence between these “varieties” of welfare capitalism. Further tests of the reliability of our findings would require extending our analysis to other countries or regions, but at the same time retaining a fine-grained measure of financial volatility consistent with the data used here.

Lastly, as a result of issues of multicollinearity discussed above, we were unable to include several control variables that are commonly used to examine institutional determinants of CSR. In our robustness tests (models 4 and 5) we replaced competition index with two alternative indicators: legal system and labor-employer relations. Given their highly-correlated nature, it is perhaps not surprising that these alternative indicators, like the competition index, show no significant differences in any of our models. More importantly, by changing model specifications we did not affect the findings in our main models and hence there is little evidence that the main models are not sensitive to these changes in model specifications.

Conclusions

Our analysis examines the determinants of CSR reporting and, in particular, the effects of the financial crisis and public scrutiny on CSR reporting of firms operating in the financial sector. Our main aim was to present and test a more theoretically rigorous framework for how financial volatility and visibility impacts firms’ CSR decisions. As such, we build on recent advances in the CSR literature related to institutionalism. We also challenge the view that firms will jettison CSR commitments during times of economic hardship and financial volatility. We argue that financial crises carry important non-economic costs, especially those related to a firm's position in society, declining levels of trust, and the fear of more stringent national and supranational regulation. Financial crises, or moments of extreme financial volatility, have demonstration effects that can implicate firms from certain economic sectors in a crisis and thereby shine a light on their behavior. The news media also plays an important role in drawing public attention to these same firms. Taken together, demonstration effects can drive firms to rebuild public trust by engaging in more extensive reporting on their CSR commitments.

We tested these arguments using a unique dataset. Results supported two of our hypotheses: increased financial volatility and increased public scrutiny are strongly and positively correlated with more extensive CSR reporting. However, our results show that financial service providers are not uniquely susceptible to the pressures related to firm visibility even during times of extreme financial volatility. Instead, our findings show that finance is slightly more resistant to these effects. While financial firms do tend to respond to public scrutiny by engaging in more extensive CSR reporting, this effect is not proportional to the extreme levels of public scrutiny they faced during the height of the financial crisis.

Our analysis contributes to a growing literature on the institutional determinants of CSR. In addition to challenging the view that economic hardship has a negative impact on CSR, our analysis builds on recent research in the field of international business studies. In particular, while most studies examine financial crises using a dummy variable for the crisis, we use a fine-grained measure that captures the transnational and systemic character of financial volatility. Moreover, we include an indictor measuring public scrutiny that captures news media attention both nationally and internationally.

Our analysis focused exclusively on EU firms. This had the benefit of allowing us to control for various contextual factors that are otherwise difficult to observe in statistical analyses of this kind. Nevertheless, the question remains about generalizing our findings beyond Europe. To what extent, for instance, have U.S.-based firms reacted to the same pressures in the same ways? Further studies could use our approach to examine demonstration effects and public scrutiny in different contexts and perhaps also for longer time periods. Barring that, scholars could also expand on our dataset by including more European countries. Eastern European countries are unfortunately absent from our dataset (a function of data availability). While these data are not readily available in the GRI data, one approach would be to merge GRI data with other sources, like the Dow Jones Sustainability Index and the KMPG International Survey of CSR Reporting. The challenge of doing this, however, is determining how to merge data that tends to measure the same thing but in different ways. Indeed, part of the larger problem is settling on a definition, and consequently measurement, of CSR. As Votaw (Reference Votaw1972, 25) pointed out decades ago, “corporate social responsibility means something, but not always the same thing to everybody.” Further, our empirical analyses focused on the reporting of CSR, assuming a close interconnection between actual CSR commitments and CSR reporting. Further research should test whether firms actually increase both their CSR reporting and their CSR activities, or that the CSR reporting is rather symbolic, and firms simultaneously decrease actual investment in CSR.

Our results have specific scholarly and policy implications. First, while not our primary focus, our analyses found only little evidence supporting many of the main explanations of CSR in the existing literature. Specifically, we found little evidence that labor-employer relations, consumer confidence, quality of management schools, inflation, or a country's legal system have any bearing on CSR reporting. This stands in sharp contrast to leading existing studies. Of the “usual suspects,” only competition, business confidence, and sector impact appear to affect a firm's reporting on CSR commitments. These results, especially as they relate to labor-employer relations and quality of management schools, have direct policy implications. Policies meant to enhance CSR based on manipulating these factors are therefore very likely off base. Instead, a firm's decision to engage in, and report on, CSR is far more a function of exogenous factors that governments would be hard pressed to transform into policy initiatives. This finding also supports the view that most CSR reporting is “reactive” rather than “proactive.” As our results show, extreme financial volatility and increased news media attention are key to getting firms to engage in more extensive reporting on their CSR efforts. Pressure to increase CSR commitments have less to do with a firm's bottom line and more to do with non-economic concerns over their public reputation and perceptions of trust amongst the general public.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/bap.2018.28.