Introduction

Former lobbyist Jack Abramoff's guilty plea on 3 January 2006, is supposedly the most serious example of a lobbying corruption scandal in US history. This unprecedented scandal raised serious concerns over the use of lobbyists. It also stigmatized other firms that engaged in lobbying. Before the Abramoff scandal, the lobbying industry had grown by 8 percent on average during the previous eight years. In 2006, the year of the Abramoff scandal, the lobbying industry showed a growth rate of 1.7 percent. Abramoff's scandal left a prominent scar on the lobbying industry and firms engaged in lobbying.

According to expectancy violation theory, social disapproval of culpable firms leads people to reappraise their prior expectations of these firms. Shareholders may believe that some business operations are violating broader social norms.Footnote 1 Moreover, firms sharing similarities with culpable firms also experience negative spillover.Footnote 2 Even though these bystander firms were not convicted in court, they were nevertheless stigmatized by shareholders.

How, then, do stigmatized bystander firms recover their legitimacy? The memory of an illegal wrongdoing stays in people's minds for quite some time. In this situation, even though firms may launch a variety of firm-initiated antidotes, the proposed remedies have severe limitations in integrity violation cases.Footnote 3 In this situation, institutional remedies that increase transparency can effectively mitigate such concerns. At a time of vulnerability, credible third-party involvement can effectively recover a firm's lost legitimacy.Footnote 4 Institutional remedies that curtail the downside risk associated with culpable behavior can significantly increase the firm's transparency and credibility.

To test our hypotheses, we use two events around the Abramoff scandal. First, we examine shareholders’ reactions to the negative spillover of stigmatization using the guilty plea of the notorious lobbyist Jack Abramoff in 2006. Second, we show how an institutional remedy works as a legitimacy-restoring device by introducing the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act (HLOGA) of 2007.

We use firms’ stock performance to explore shareholders’ reactions. Previous literature has focused on shareholders’ reactions to schema-relevant information,Footnote 5 as stock performance is one of the most important performance indicators. Along these lines, we focus on shareholders’ reactions in our study.

Focusing on S&P 500 firms from 2000 to 2007, we find that shareholders penalized firms that engaged in lobbying. Among firms that lobbied, those bystander firms with supposedly more dubious connections (such as those that had revolving-door lobbyists) were punished more. We contribute to the literature by showing how expectancy violation can be restored by an institutional remedy. We find that the firms that received more penalties enjoyed more favorable reactions from shareholders following the announcement of a legal remedy, given that a third-party remedy helped restore their legitimacy. We also find that firms with more revolving-door lobbyists experienced additional legitimacy restoration and credit from their shareholders.

The remainder of this article proceed as follows: We first introduce our empirical context. Next, we discuss categorization theory and expectancy violation theory. Then, we develop our theoretical arguments, which explain negative spillover to bystander firms and their potential to regain credibility. Then, we establish the hypotheses tested in our study. Next, we specify how we test our hypotheses and explain our results. In the empirical section, we introduce another study to test our hypotheses, focusing on the Enron scandal and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Finally, we discuss our findings and limitations of the study.

Context

Lobbying is a nonmarket strategy in which “a concerted pattern of actions taken in the nonmarket environment [creates] value by improving its overall performance.”Footnote 6 Overall firm performance is determined by the social and political context of the environment.Footnote 7 Scholars have considered nonmarket strategies as critical strategic behaviorsFootnote 8 and have largely examined the positive effect of nonmarket strategies on firms.Footnote 9 By the 2000s, nonmarket strategies had become recognized as a wide field of research.Footnote 10 Nonmarket strategies are divided into strategic corporate social responsibility and corporate political activity (CPA).Footnote 11 Specific CPA strategies include participation in trade associations, testimony before Congress, campaign contributions, donations, participation in political action committees (PACs), and lobbying.Footnote 12

Along the lines of corporate political activity research, past studies in lobbying have found that lobbying activities in many countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom, have led to positive performance outcomes, such as more government contractsFootnote 13 or less litigation.Footnote 14 Mostly, lobbying studies have argued that lobbying can “buffer” regulations and “bridge” firms with lawmakers.Footnote 15 By buffering, these firms can shape public policy,Footnote 16 decrease regulation,Footnote 17 and bargain with lawmakers.Footnote 18 Generally speaking, shareholders want to see increased firm performance by engaging in strategies, whether they are market or nonmarket strategies. It is no surprise that the stock market reacts favorably to firms’ lobbying activities. For example, using event study methodology, Brodmann, Unsal, and Hassan found that firms that invested in lobbying expenditures gained higher cumulative abnormal returns before the announcement of firm-sponsored bills that passed in the US Congress.Footnote 19 They used the events of 2,554 bills passing in the US Senate and House of Representatives.

Similarly, Hassan, Unsal, and Hippler confirmed that shareholders showed favorable stock reactions on the date of a firm's class-action announcement when the firm engaged in lobbying.Footnote 20 Their finding illustrates shareholders’ belief that lobbying boosts firm value. Primarily, studies involving shareholders’ reactions to firm lobbying have investigated shareholders’ positive reactions.

However, on 3 January 2006, one of the most calamitous events in the US lobby industry took place. The former lobbyist Jack Abramoff was found guilty of corrupting government officials in the United States. He was a lobbyist for Native American tribes seeking to develop casino facilities on their reservations. Birnbaum and Balz described this corrupt lobbying case as “the biggest corruption scandal to infect Congress in a generation.”Footnote 21 It is unsurprising that “as a condition of the plea, Abramoff provided evidence that led to the conviction of more than 20 elected representatives, congressional staff, and executive branch officials.”Footnote 22

After Abramoff pled guilty in court in 2006, many politicians, including Senator Barack Obama, collectively argued that more transparency was necessary to prevent corrupt lobbying. It was generally agreed that the 1995 Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA) was not enough to block corrupt lobbying activities. The required information disclosure on lobbying in the 1995 LDA was insufficient in providing enough transparency. The 1995 LDA also lacked sufficient regulations on revolving-door lobbyists, a considerable source of opacity in lobbying. In response to the call for a stricter law, the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act was introduced in 2007. In addition to higher requirements for preparing lobbying reports, HLOGA required a one-year ban that would forbid revolving-door lobbyists from contacting former colleagues in the government.Footnote 23 HLOGA was finally enacted on 14 September 2007.

Leveraging Abramoff's lobbying scandal, Borisov, Goldman, and Gupta found that lobbying firms receive more hostile reactions from their shareholders when a catastrophic scandal occurs.Footnote 24 Furthermore, these reactions worsen if firms use a higher percentage of revolving-door lobbyists. Their study sheds light on the negative responses of shareholders to a firm's lobbying activities. However, even though this study made considerable contributions to the lobbying literature, it did not capture the same shareholders’ flipped responses when the government introduced stricter rules on lobbying. Thus, in this article, we broaden previous studies on shareholders’ responses to lobbying using two events—one negative and one positive.

Previous scholars have documented that regulatory reforms influence shareholder value positively. Using an event study, Lin et al. reported that the announcement of anticorruption reforms in China in 2012 increased shareholder value.Footnote 25 Interestingly, the firms that bribed less before the regulation reforms benefited more from the legal remedy. Where market institutions were more developed, anticorruption reforms increased shareholder value more, and broken political connections mattered less.

A similar event study in IndiaFootnote 26 showed that regulatory reforms concerning corporate governance increased shareholder value for firms in India. Clause 49, proposed in 1999, requires public firms to be more transparent. To do so, these public firms must implement “audit committees, a minimum number of independent directors, and CEO/CFO certification of financial statements and internal controls.”Footnote 27

Not all regulatory reforms, however, have increased shareholder value. In the United States, the impacts of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act on shareholder value have been negative.Footnote 28 Upon the introduction of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, firms cross-listed on the stock market experienced a decrease in shareholder value, indicating that the stock market expected high-disclosing firms to experience more costs because of an increased regulatory burden. In addition, firms from countries with more transparent corporate governance than the United States suffered more, suggesting that shareholders may consider such oversight as “regulatory overkill.”Footnote 29

Theory Development

Integrity violations happen when a person or an organization does not comply with social norms. Past research has found that integrity violations elicit an exaggerated response and are punished excessively.Footnote 30 Unlike capability failures, integrity failures lead people to be concerned about the motivation behind the wrongdoing.Footnote 31 According to Connelly et al., an integrity failure refers to “a specific situation wherein the firm's motives, honesty, and/or character fall short.”Footnote 32 Violating moral expectations is much costlier than violating capability (ability to execute) expectations.Footnote 33 For example, when Arthur Andersen was caught in an integrity expectation violation, regardless of the firm's capabilities, the stock market penalized its clients. As a result, the maximum penalty is levied on the culpable firm when illegal activity is revealed.Footnote 34

At the same time, people categorize the social world by classifying “social space into groupings of actors or objects with similar characteristics, and such groupings facilitate social actors’ schematic processing and sensemaking of the world around them.”Footnote 35 By classifying social space in this manner, “categories provide a cognitive infrastructure that enables evaluations of organizations and their products, drives expectations, and leads to material and symbolic exchanges.”Footnote 36 Thus, this categorization helps people reduce their information-processing needs.Footnote 37

Taken together, expectancy violation theory and category theory suggest that people expect firms to behave in compliance with social norms. Violating this expectation is very costly for firms. However, the penalty attached to an expectancy violation is not limited to culpable firms; it also spills over to bystanders that share similar characteristics with the culpable firms. At the time of the expectancy violation and the spillover of a bad reputation, bystander firms can hardly prove that they are not culpable.

Many studies on negative spillover focus on specific industries and show how a focal firm's wrongdoing can affect other firms in the same industry.Footnote 38 This approach makes sense, given that shareholders categorize firms with similar characteristics to lessen their cognitive burden in understanding firms, such as using the industry as an easy-to-recognize category.Footnote 39 Roehm and Tybout used an experiment to show that a negative spillover happened within the same product category when a scandal involved commonalities between the brand and its competitor. In other words, a hamburger scandal at Hardee's would generate negative spillover effects to Burger King.Footnote 40 In addition, Volkswagen's emissions scandal negatively spilled over to its industry rivals (e.g., Ford and BMW).Footnote 41

Interestingly, scholars have increasingly spotted the phenomenon that a spillover could happen across industry boundaries as well. Aranda, Conti, and Wezel reported that the legalization of marijuana generated positive spillover effects to the alcohol industry.Footnote 42 Given that marijuana has medical benefits, alcohol has been purported to be “safe and even beneficial for health.”Footnote 43 The legalization of marijuana led the public to reconsider the vilified image of the alcohol industry. If positive spillover can happen across industries, the same could be true for negative spillover. When does a spillover happen across industries? When the strategic behavior associated with the catastrophic event encompasses many industries, the stigmatization associated with such strategic behavior works as a category setter. Moreover, the firms exhibiting similar strategic behavior will be classified as a stigmatized category, differentiating themselves from firms that do not exhibit similar strategic behavior. This phenomenon is considered “stigma by association.”Footnote 44 For this reason, scholars suggest that stigma can be “a vilifying label that contaminates a group of similar peers.”Footnote 45

Ocasio argues that what “the decision-makers focus on, and what they do, depends on the particular context in the situation they find themselves in (Situated Attention).”Footnote 46 Andrews et al. further explain that “individuals are rational but have limited attentional capacity, which influences their situational assessment and forms subsequent action.”Footnote 47 How does a society recognize an external event that influences situated attention? With a critical event, investors and people may realize the political activities of each firm in which they invested. The public will begin its situational assessment once a corrupt scandal is debunked. At times, public attention can even trigger institutional transformation.Footnote 48 Observers, including shareholders, begin to pay attention to newly emerging information about firms once a rare crisis happens.Footnote 49 In the case of corrupt lobbying scandals, the newly highlighted information includes the firm's previous political activities and the possibility of engaging in unethical lobbying. The level of relatedness to the scandal (e.g., the level of engagement in lobbying and the ratio of hiring revolving-door lobbyists) can provide new evaluative tools for shareholders.

Consequently, lobbying works as a category setter when a strategic behavior is shared with other firms. For example, Dixon-Fowler, Ellstrand, and Johnson found that female CEO appointments decreased other female-led firms’ share prices by approximately 0.58 percent.Footnote 50 The emergence of attribution due to the categorization of all female CEOs taints the image of bystanders with female CEOs, leading to deteriorated firm value. As this example shows, the conceptualization of a taken-for-granted industry category gives way to a new categorization when a particular attribute or strategic behavior attracts salient attention.Footnote 51

Beyond the easily visible and taken-for-granted category setter such as an industry, a salient wrongdoing associated with a strategic behavior can also be a category setter.Footnote 52 Here, a taken-for-granted categorization occurs based on homogeneity.Footnote 53 By being grouped into a stigmatized category, firms associated with stigmatized strategic behavior are considered culpable.Footnote 54 Such a spillover of culpability is also known as “categorical delegitimization.”Footnote 55

Utilizing this concept, we examine how an entity's corrupt lobbying behavior can penalize bystander firms. Even when shareholders demand to monitor firms’ lobbying activities,Footnote 56 they assume that firms are generally expected to behave in a socially accepted manner.Footnote 57 Shareholders typically believe that lobbying will be done responsibly in good faith by ideal political citizensFootnote 58 in public politics.Footnote 59 Illegal lobbying activities violate shareholders’ expectancy, resulting in legitimacy loss.

Shareholders witnessing corrupt lobbying will assume a high possibility of bystander firms engaging in a similar wrongdoing.Footnote 60 Given that corrupt lobbying is an integrity-violating wrongdoing in which the very motive is questioned, the spillover of culpability can be severe for bystander firms under the same lobbying category.Footnote 61

A bystander firm is deemed culpable when the firm falls under the same category as the culpable firm.Footnote 62 When bystander firms are cognitively grouped under the same category, they become similarly stigmatized. Here, stigma refers to the notion that “once connected to stereotypes, firms are generalized to groups of similar peers since categories are, per definition, groupings based on perceptions of similarity.”Footnote 63 Yet not all firms categorized under the culpable category are stigmatized at the same level. When a strategic behavior is stigmatized, the level of association with the stigmatized behavior will be commensurate to the level of culpability. The variance in culpability will be present within a category.Footnote 64 Bystanders sharing higher associability with the stigmatized behavior are seen as more salient in the shareholders’ eyes. They receive a more significant penalty from a higher level of “guilt by association.”Footnote 65 For example, active engagement in lobbying shows a strong association with lobbying, which is stigmatized around the scandal. These firms will be subjected to more suspicion (compared to firms that lobby less) from their shareholders. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H1: Bystander firms that engage in more lobbying will experience more market value decreases when a stigmatizing scandal occurs.

Lobbyists’ main assets are the people they know,Footnote 66 as relationships grant firms access to political insiders. By leveraging those relationships, politically connected firms take advantage of them.Footnote 67 For this reason, McGrath states that the three most essential things in lobbying are “contacts, contacts, contacts.”Footnote 68 In the lobbying industry, connections are scarce resources that are pivotal to lobbying.Footnote 69 When choosing lobbyists close to politicians and government officials, there are no better candidates than ex-politicians and ex-government officials. These so-called revolving-door lobbyists are valuable in obtaining favorable political outcomes for lobbying firms.Footnote 70 Revolving-door lobbyists are individuals with “personal connections through previous employment [who] thoroughly understand the legislative process.”Footnote 71 Past research has found that more than half of all lobbyists hired by firms are former congresspeople or Senate members.Footnote 72 Because “Washington is all about connections,”Footnote 73 McCrain showed that a 1 standard deviation increase in having private connections through revolving-door lobbyists is associated with an 18 percent increase in revenue.Footnote 74 This happens because revolving-door lobbyists have better access to political insiders than their non-revolving-door counterparts.

Once a corrupt lobbying scandal is revealed, a firm with more revolving-door lobbyists appears more suspicious. The higher suspicion associated with revolving-door lobbyists will generate greater dismay in the shareholders. The stronger the anger is from shareholders’ dismay, the higher the potential there is for moral hazard, referred to as “betrayal aversion.”Footnote 75 This is because shareholders assume that lobbying will be conducted in good faithFootnote 76 in public politics.Footnote 77

With respect to utilizing private connections, shareholders find it difficult to gather information on how revolving-door lobbyists work. The increased information gap regarding a firm's lobbying activities (from the shareholders’ standpoint) could exacerbate their concern regarding the firm's likelihood of participating in illegal lobbying activities. According to categorization theory, shareholders fill in missing information by leveraging other firms’ information.Footnote 78 By doing so, shareholders assume that their firm's behavior may work similarly to the culpable firms’ behavior.

Further, when the wrongdoing is associated with a lack of transparency, the stigma spillover of the firm's behavior is exacerbated. Such a lack of transparency leads shareholders to imagine the worst. For example, if firms used more revolving-door lobbyists with private connections, shareholders’ concerns would increase with regard to the firm's possibility of engaging in illegal lobbying activities. When shareholders notice that personal connections with politicians are pivotal in the wrongdoing, firms that hire revolving-door lobbyists will also be deemed culpable. Those firms that frequently engage in lobbying will lose more credibility. Therefore, we argue:

H2: Among bystander firms, firms that engage more in lobbying and have a higher ratio of revolving-door lobbyists will experience more market value decreases when a stigmatizing scandal occurs.

Ingram and Clay classified institutions as (1) public or private and (2) centralized and decentralized.Footnote 79 The state often runs public institutions. Private institutions are usually voluntary because the rules cannot be forced on all entities: “In the centralized form of these institutions, a central authority sets rules, incentives, and sanctions for noncompliance.”Footnote 80 This is not the case concerning decentralized institutions. These institutions need a powerful authority with the right to impose sanctions. This characteristic of sanctions for noncompliance by centralized public institutions creates credibility for institutional remedies to fix integrity failures.Footnote 81 When the negative impact of a wrongdoing spreads beyond the culpable firm, both the culpable firms and bystander firms try to remedy the situation. However, it is difficult to regain lost legitimacy from the shareholders.Footnote 82 These shareholders doubt the true intention behind such moves,Footnote 83 given that any strategic moves are firm-discretionary actions. Self-made efforts by firms that have lost legitimacy are less impactful in stopping or reversing the negative spillover of the wrongdoing.Footnote 84 There are limitations to firm-strategic moves in curtailing the negativity spilled over from outside the firm.

In contrast, an institutional remedy can increase the transparency and credibility of a firm's discretion in this situation. When a credible third party develops a new institutional arrangement that decreases the likelihood of potential violations regarding shareholders’ expectations, the stigma levied on bystander firms will lessen. Pozner, Nohliver, and Moore showed that improvements in external monitoring by governments result in increased firm reliability.Footnote 85 Legal remedies decrease firms’ chances of a wrongdoing by enforcing a stricter monitoring system and heightening transparency. This argument supports the notion that external monitoring can substitute for the failure of firms’ internal controls.Footnote 86

Prior research has found that audiences assign more value to institutional remedies compared to firm-initiated rehabilitative efforts.Footnote 87 Perceivers believe that corrections initiated by a trustworthy third party are objective with a low possibility of manipulation, even when only incomplete information about the particular action is available.Footnote 88 Therefore, legitimacy restoration occurs when new regulations mitigate concerns about a wrongdoing. It is natural for an institutional correction to receive favorable reactions from perceivers.

Among the bystanders tainted by the negative spillover of a wrongdoing, those firms associated more with the culpable stigmatized strategic behavior will be penalized more. Accordingly, at the time of the legal remedy, those firms that were penalized more will experience more legitimacy recovery. Given that the legitimacy rehabilitation is the action of a credible third party, institutional remedies assure that all firms will be expected to satisfy the minimum requirements due to the third party's sanction power.Footnote 89 Those firms penalized more at the time of the disclosure of corrupt lobbying may enjoy enhanced legitimacy restoration when the new lobbying regulations are introduced. Thus, we posit the following:

H3: Bystander firms that engage in more lobbying will experience more market value increases when a credible third party announces a legal remedy.

Introducing a new institutional remedy for an integrity failure with compulsory requirements and credible sanctions gives shareholders assurance that the wrongdoing is unlikely to happen again in the future.Footnote 90 When a new institutional remedy is introduced, those penalized firms will receive the most credit. The information gap and lack of accessibility will be highest for strategic behaviors characterized by the most insufficient information to shareholders. When a credible third party—a central public authority—takes control and promises potential sanctions if firms fail to abide by the rules, credibility gains will be highest for those associated with the highest penalty.Footnote 91 This is in line with expectancy violation theory in that “when a negative expectation is positively violated, a very intense positive emotional reaction ensues, which overcomes any initial negative feelings generated by the violation of expectations.”Footnote 92

A credible remedy to fix the underlying problem of an integrity violation will allow shareholders to reassess and make new judgments about bystanders painted with the same brush.Footnote 93 Past research has found that using highly connected revolving-door lobbyists will increase the likelihood of being involved in illegal activities.Footnote 94 A one-year ban on former government officials becoming revolving-door lobbyists works to loosen the tight connection between these lobbyists and government officials, thereby enabling bystanders to recover from the stain of illegitimacy.Footnote 95 For this reason, firms with more revolving-door lobbyists will recover more of their legitimacy when they engage in additional lobbying. Because the loss of legitimacy from the negative expectancy violation is more significant, the institutional remedy can help those firms (that engage in lobbying more and that hire more revolving-door lobbyists) enjoy more legitimacy rehabilitation. Thus, we argue the following:

H4: Among bystander firms, firms that engage more in lobbying and have a higher ratio of revolving-door lobbyists will experience more market value increases when a credible third party announces a legal remedy.

Method

Data and Sample

To create the sample, we merged diverse data sources. First, we collected Standard and Poor's (S&P) 500 firm lists from 2000 to 2005. Excluding duplicate firms, we had 651 firms. Second, we collected firms’ cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) using data from Thomson Datastream. Because of missing values in calculating the CARs, we were left with the stock price movements of 563 firms. Third, we collected firms’ lobbying activities from 2003 to 2005 using data from the Center for Responsible Politics. In our sample, 356 of the 563 firms lobbied from 2003 to 2005. Fourth, we collected other firm-level financial and accounting data from Compustat. Fourth, we added the industry regulation, each firm's level of diversification, and each firm's visibility. Lastly, we excluded firms if they had confounding events around the guilty plea (Event 1, the guilty plea on 3 January 2006) and the event of a legal remedy (Event 2, HLOGA was passed in the Senate on 18 January 2007). After merging all the data, 171 firms remained for Event 1, and 93 firms remained for Event 2. More firms were dropped in Event 2 because of confounding effects, delisting, and acquisitions.

Measures

Dependent variable

We selected firms’ abnormal returns to capture their reactions to the two events and used the event study methodology.Footnote 96 A firm's CAR was calculated using a two-day window (–1, 0), following McWilliams and Siegel (Reference McWilliams and Siegel1997), who noted that a period of two days would not capture the effect of the event's impact on the CARs. We multiplied two dependent variables by 100 to generate the percentages. Following the previous study,Footnote 97 we examined the stock price movement around the announcement of Abramoff's guilty plea on 3 January 2006, to capture the adverse reactions of investors. We also captured HLOGA's passage in the Senate on 18 January 2007. Among the essential dates regarding HLOGA, we chose the date that the Senate passed the law because it clearly showed that a legal remedy would be implemented. From the shareholders’ view, introducing the new law in the Senate was not enough to gauge the possibility of the new lobbying act passing. However, once it was passed, the shareholders could regard this new regulation as highly likely to be enacted. The fact that the Senate passed the law meant that newer and more impactful information was available to them.Footnote 98 In addition, after the Senate passed HLOGA, its fate was quite predictable, as 83 of 100 senators voted for the new law.Footnote 99 This tendency was replicated in the House of Representatives. When HLOGA was passed in the House of Representatives, 411 of 432 voted in favor of it.Footnote 100

Independent variable

For Event 1, following measurement used by Borisov and colleagues, we gathered the total lobbying expenditures from 2003 to 2005.Footnote 101 Because the corrupt lobbying conviction occurred in 2006, we added the previous three years of lobbying expenditures. For Event 2, we collected how much firms spent on lobbying in 2006. After the announcement of Abramoff's guilty plea in January 2006, firms’ lobbying expenditures in 2006 reflected their lobbying behavior after the guilty plea. We logged the lobbying expenditures for Events 1 and 2 to reduce skewness.Footnote 102

Moderating variable

We measured the use of revolving-door lobbyists to capture their closeness to politicians and government officials. The Center for Responsive Politics provides information on lobbyists’ work experience in the government. We used this data, which captured lobbyists’ previous official positions in the government (e.g., lawmakers and employees who worked for the legislature or executive branch). For example, if a lobbyist had worked as the former chief counsel to the Senate Commerce Committee, we regarded this individual as a revolving-door lobbyist. To create the moderating variable, we counted the firm's total number of lobbyists and revolving-door lobbyists during two periods: (1) from 2003 to 2005 and (2) in 2006. We then divided the number of revolving-door lobbyists by the total number of lobbyists to calculate the ratio.

Control variables

We controlled for firm size, as it is highly related to lobbying activities.Footnote 103 We measured firm size using total assets (logged). Following previous research,Footnote 104 we controlled for firm performance using the return on equity (ROE). Because our dependent variable is the stock price movement, ROE is a better measurement than the return on assets (ROA) to capture firm performance. We controlled for industry effects using SIC one-digit classifications. To control for the influence of another crucial political strategy, political action committee (PAC) contributions were controlled using the log of the total number of PACs. Finally, we controlled for whether a firm was in a high regulation industry, as many previous studies have indicated that firms in a regulated industry have more incentives to lobby.Footnote 105 Following the previous study's method,Footnote 106 we coded 1 as firms in a highly regulated industry, and 0 otherwise. We also controlled for lobbying breadth. We measured the average number of agencies involved in lobbying.Footnote 107

In addition, we controlled for several financial variables that could affect the hypothesized relationships. First, we controlled for liabilities, measured by the ratio of assets to liabilities.Footnote 108 Second, we controlled for Tobin's Q, calculated as the market value divided by its replacement value.Footnote 109 Third, we controlled for the tangibility ratio, measured by tangible to total assets.Footnote 110 Additionally, we controlled for return uncertainty, calculated as the standard deviation of the daily returns of each firm from 275 to 30 days before Events 1 and 2, respectively.Footnote 111

We controlled for the media visibility of each firm. For Event 1, we counted the number of Wall Street Journal (WSJ) articles reporting on each firm from 1 January 2003 to 2 January 2006. For Event 2, we searched the number of WSJ articles from 4 January 2006 to 17 January 2007. We then logged the number of articles. More visible firms tend to increase their lobbying activities. Additionally, more visible firms would attract further attention.

We controlled for industry regulation as a regulation probability using RegData.Footnote 112 Al-Ubaydli and McLaughlin calculated the regulation probability for each industry based on two factors: texts in federal regulations and their relevance to each industry.Footnote 113 Under highly regulated industries, firms have incentives to lobby the government to set favorable rules and standards for their firms. For Events 1 and 2, we used RegData for 2005 and 2006, respectively. In addition, some firms may operate in multiple industries, which could impact the firms’ categorization. Therefore, we controlled for diversification. The level of business diversification for each firm was measured by the Berry-Herfindahl index.Footnote 114 We obtained the data from the Compustat business segment data.Footnote 115 We first calculated the Herfindahl-Hirschman index from the business segment data for each firm. We then deducted the value from 1 to create the Berry-Herfindahl index.

Finally, we added Team Jack, given that Abramoff engaged in illegal lobbying with his team members, and some were also found guilty in court. Thus, following the previous literature,Footnote 116 we controlled for Team Jack by creating a ratio variable indicating firms that hired the twenty-one lobbyists on his lobbying team. There is the possibility that shareholders may show more adverse reactions to firms associated with Team Jack.

In analyzing Event 2, we used additional variables to capture the firm's changed nonmarket behaviors after the guilty plea announcement. First, we controlled for the change in lobbying expenditures. The difference between the firm's lobbying expenditures in 2006 and its average expenditures from 2003 to 2005 was calculated and divided by the average lobbying expenditures from 2003 to 2005. Second, a PAC contribution change was added. The PAC contribution difference between PAC contributions during two periods, (1) from 2003 to 2005 and (2) in 2006, was calculated and divided by the average PAC contribution from 2003 to 2005. Furthermore, we added several change variables. Following the same way of measurement, we added revolving-door lobbyists’ change and lobbying breadth change.

Empirical strategy

We argue that lobbying firms will experience a more negative market reaction around the announcement of the verdict from the court (Event 1) and a more favorable market reaction around the legal remedy (Event 2).

The abnormal return (AR) on stock j of day t is estimated by:

Rjt is the daily stock return of stock j at time t, and $\widehat{{R_{jt}}}$![]() is the expected daily stock return on stock j at time t. ARjt is the actual daily stock return minus the expected daily stock return.

is the expected daily stock return on stock j at time t. ARjt is the actual daily stock return minus the expected daily stock return.

N denotes the number of sample companies. CAR t for the event window [–1, 0] is the sum of abnormal returns in the two days.Footnote 117 The formulation is as follows:

In this equation, j denotes each company; t denotes time; t 1 is the beginning date (–1); and t 2 is the event window's ending date (0). We use –210 to –11 days; thus, the estimation window covers 200 trading days. We exclude firms with fewer than 30-day stock returns. Following the method of previous studies, we tested different windows as the robustness check. We found that a more extended (e.g., [–2, 1]) window shows the impact of the guilty plea and the passage of the new lobbying act in the Senate on the shareholders’ responses.

Results

We argue that lobbying firms will experience a more negative market reaction around the announcement of the verdict from the court (Event 1) and a more favorable market reaction around the passage of the new act (Event 2). This also means that lobbying and non-lobbying firms should experience different stock market movements around the two events. For example, when Jack Abramoff pleaded guilty, lobbying firms should have received more hostile reactions from the shareholders, compared to non-lobbying firms. Conversely, applying the same assumption, lobbying firms should have gotten more favorable responses from the shareholders than non-lobbying firms when the new lobbying act was launched. To test the different reactions around the two events, we create a matched sample with firms that did not engage in lobbying between 2003 and 2005 using SIC industry classifications (SIC one-digit) in the listed firms. Then, we use propensity score matching based on firm performance (ROE) for Events 1 and 2.

We conducted two separate analyses. For Event 1, we tested the difference between the CARs of firms engaged in lobbying and those of firms that did not lobby around Abramoff's guilty plea. We calculated a two-day event window (–1,0). For Event 1, the CAR for lobbying firms is –0.76 percent, whereas the CAR for non-lobbying firms is –0.55 percent, and the difference is statistically significant based on the t-test result (t = 4.4392). We gain the same results from different CAR ranges, such as a three-day window (–1, +1). Thus, we confirm that lobbying firms experience harsher reactions from their shareholders when the corrupt lobbyist is punished.

Table 1. Matching results: Differences in CAR between lobbying and non-lobbying firms at Event 1.

Also, for testing Event 2, we examined the difference in the CARs of firms that participated in lobbying and not around the passage of HLOGA in the Senate. We use the same two-day event window (–1, 0). Table 4 shows that the CAR for lobbying firms is 0.73 percent. In contrast, the CAR for non-lobbying firms is 0.66 percent, and the difference is statistically significant based on the t-test result (t = –2.5142). Results with a three-day window (–1, +1) and a different two-day window (0, +1) are qualitatively the same. Consequently, we find that lobbying firms receive more positive responses from their shareholders than non-lobbying firms.

Table 2. Matching results: Differences in CAR between lobbying and non-lobbying firms at Event 2.

After we certify that lobbying and non-lobbying firms show different stock price movements around the two events, we run two different regressions. Thus, we have two descriptive statistics tables. Tables 3 and 4 present all variables’ descriptive statistics and correlation matrices for each event. We find that lobbying expenditures in 2006 and lobbying expenditure changes in Table 4 are highly correlated. We orthogonalize the two variables using the Gram-Schmidt procedure to mitigate potential problems.Footnote 118 By removing the common variance, this technique creates transformed uncorrelated variables with each other.Footnote 119

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and pairwise correlation matrix, lobbying scandal, Event 1. N = 171.

* Significant at the .05 level.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics and pairwise correlation matrix, lobbying scandal, Event 2. N = 93.

* Significant at the .05 level.

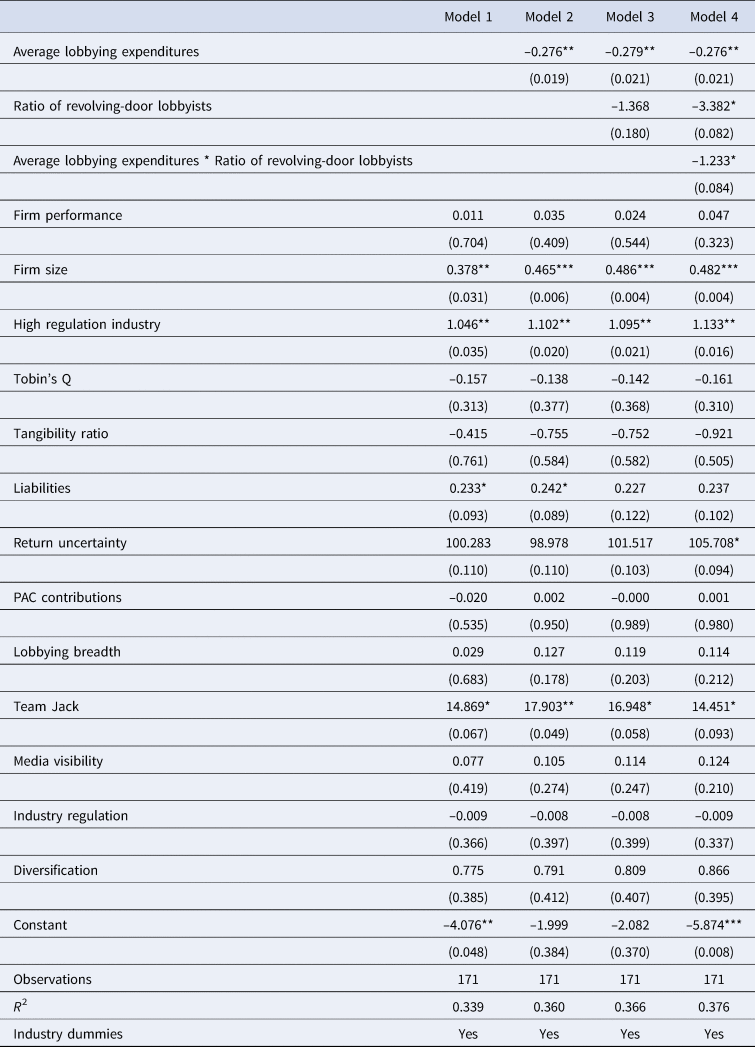

Model (1) in Table 5 contains only the control variables. Model (2) shows a negative relationship between lobbying expenditures and CAR. When the firm participated more actively in lobbying, it triggered a more negative spillover effect when Abramoff's guilty plea was announced (β = –.276; p = .019), thereby supporting H1. In Model (4), we tested the boundary condition of the ratios involving the revolving-door lobbyists. The results show that having a higher level of revolving-door lobbyists magnifies the negative relationship between lobbying expenditures and CAR (β = –1.233; p = .084), thus supporting H2. A graphical representation of this interaction effect is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Interaction effect of revolving-door lobbyists on the negative relationship between the level of lobbying and shareholders’ reactions.

Table 5. Regression results, Jack Abramoff lobbying scandal, Event 1. N = 171.

Robust p-values are in parentheses: *** p < .01; ** p < .05; * p < .1.

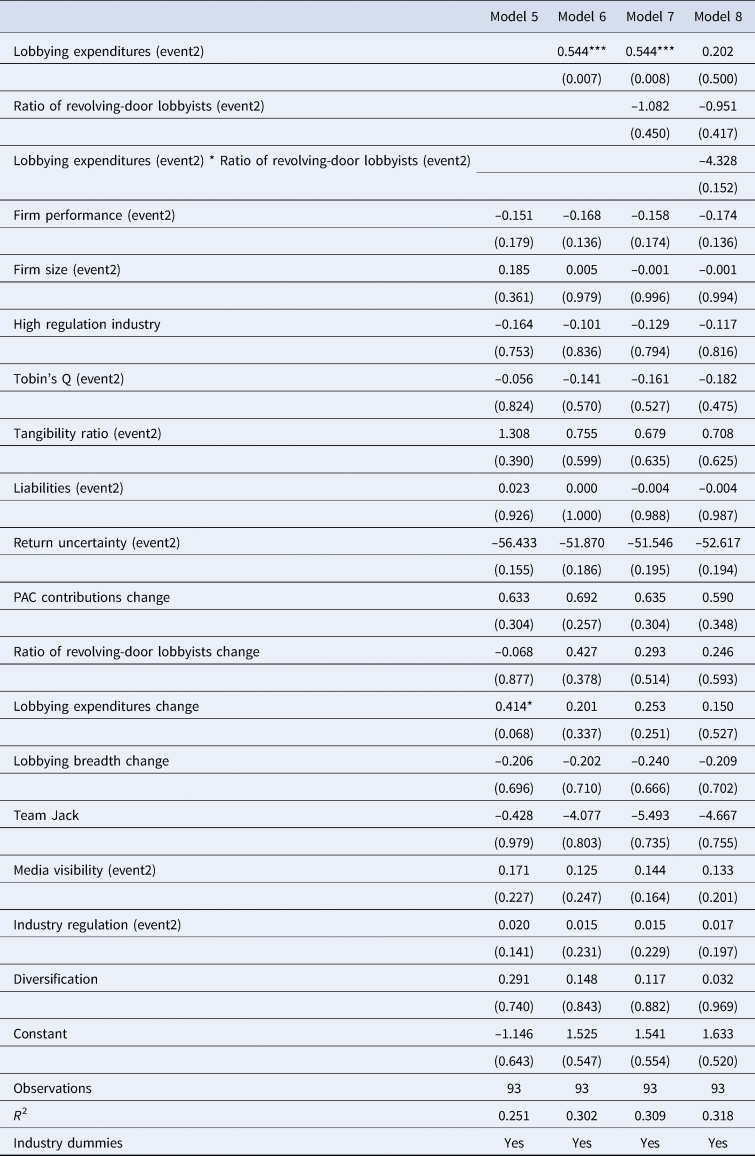

Table 6 displays the results of the positive news about lobbying (Event 2). In Model (5), only the control variables are included. Model (6) examines investors’ reactions to the announcement of amending the current lobbying law. As we hypothesized, the results confirm that investors from firms with a higher level of lobbying engagement showed favorable attitudes toward the government's external monitoring (β = .543; p = .007). Thus, H3 was marginally supported. Finally, in Model (8), we explored the moderating effect regarding the ratios of revolving-door lobbyists. The results failed to reach statistical significance (β = –4.328; p = .152). As a result, H4 was not supported.

Table 6. Regression results, legal remedy, Event 2. N = 93.

Robust p-values are in parentheses: *** p < .01; ** p < .05; * p < 0.1.

Additional Case: The Enron Scandal and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act

Because Abramoff's case is known as “the biggest congressional corruption scandal in generations”Footnote 120 in US history, this study may lack generalizability. It is quite challenging, however, to identify a comparable corrupt lobbying scandal with relevant data. We found sixteen corrupt lobbying scandals in the United States and the United Kingdom.Footnote 121 Legal remedies resulted in four cases. Out of these four cases, we could identify only one case that we could analyze with lobbying data: the Enron scandal in 2001. For the other three cases, either stock market data and/or lobbying data are unavailable (see Table A1 in Appendix A). Enron is a comparable historic corruption case that involves lobbying.Footnote 122 Because corruption can be broadly defined as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gains,”Footnote 123 the Enron case would be included in corruption cases.

Enron was one of the most powerful energy companies in the world. It was the fifth-largest firm on the Fortune 500 company list. In the middle of 2001, analysts on Wall Street began to question the credibility of Enron's financial statements. The Securities and Exchange Commission started investigating both the company and its auditor. On 8 November 2001,Footnote 124 Enron admitted its malpractice in accounting. The auditor, Arthur Andersen, was convicted as well.

The impact of the Enron scandal was not limited to Enron itself. The wrongdoing was an outcome of a collaboration with the external auditor. Shareholders at other companies abruptly had to pay attention to their own firms’ auditors. Having hired Arthur Andersen could have signaled the possibility of committing similar fraud. Due to the simple fact of using Arthur Andersen as the firm's auditor, bystander firms were categorized together with Enron and experienced negative spillover.

At the same time, shareholders were naturally more suspicious of those firms with ties to politicians. The public could not imagine a firm being that audacious in committing a wrongdoing without the backing of Capitol Hill.Footnote 125 To the shareholders’ eyes, engaging in lobbying activities was enough to worsen their preoccupations about the possibility of their firms engaging in a similar wrongdoing as Enron when they hired Arthur Andersen.

This scandal precipitated a confidence crisis in the financial markets and brought about a legal remedy—the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. In response to the Enron scandal, Senator Paul Sarbanes and Representative Michael G. Oxley introduced the bill on 14 February 2002. The Senate considered it on 8 July 2002,Footnote 126 and on 25 July 2002, the House and Senate agreed to pass the law. The newly launched law requires companies in the United States to keep more comprehensive records in their bookkeeping.Footnote 127 After the intervention of this third party, shareholders could ease their worries about firms possibly engaging in corruption. The biggest beneficiaries were the bystanders categorized with Enron that had hired Arthur Andersen. Owing to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the shareholders of those companies once again perceived their firms as legitimate. Even among those firms that had hired Arthur Andersen as their external auditor, politically connected firms enjoyed more positive responses from their shareholders.

In conclusion, the Enron scandal shares many similarities and is suitable for additional analysis. First, the Enron scandal also sparked a new categorization at the center of the scandal. Shareholders grouped firms into whether they used Arthur Andersen or not. Usually, external auditor information would not attract attention from shareholders. However, if this information becomes a critical factor in a firm's wrongdoing, it begins to push the firm into the limelight. Being categorized along with Enron became enough of a reason to punish firms in the shareholders’ eyes. Second, a credible third-party remedy followed. Owing to the introduction of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, shareholders could restore their trust in firms’ legitimacy and maintain their social expectations toward these firms. Lastly, similar to the Jack Abramoff scandal, a boundary condition exacerbated shareholders’ worries about the wrongdoing—trying to be close to lawmakers. For the reasons above, we argue that Enron is an ideal setting to reverify our findings from the Jack Abramoff scandal.

Method

Samples

We first identified S&P 500 firms for 2001 (Event 1) and 2002 (Event 2). Then, we found the CARs from the Event Study through Wharton Research Data Services. Finally, after matching the dependent variable (CARs) with the independent moderating control variables, we examined the confounding effects during the event window. Our final sample sizes for Events 1 and 2 were 192 and 175, respectively.

Measures

Many variables were identically measured, as we did in the main analysis. Table B1 shows these variables.

Dependent variable: CAR (–1, 0). We used the same measurement method as in the Abramoff lobbying scandal. The Event 1 date is 8 November 2001. The Event 2 date is 8 July 2002.Footnote 128

Independent variable: Using Arthur Andersen. We coded S&P 500 firms according to whether they hired Arthur Andersen as their external auditor in 2000 (a year before the Enron scandal was debunked) or not. We used the same binary variable for Events 1 and 2, as the time period between Events 1 and 2 is less than a year. Further, because the Enron scandal was debunked in November, firms did not have a chance to find other auditors for 2002. Thus, we used the same independent variable for both events. Finally, we determined whether the firm hired Arthur Andersen or not by reading the firm's 10-K report.

Moderating variable: Lobbying expenditures. We measured the firm's lobbying engagement by summing its lobbying expenditures before the Enron scandal. We used the same moderating variable for Events 1 and 2, as the time period between Events 1 and 2 is less than a year. We accrued the firm's lobbying expenditures from January 1998 to June 2001 and logged the variable to reduce skewness.

Control variables. Most of the controls are identical to those in our main study. However, the Enron scandal was mainly a corporate accounting and auditing fraud case with substantial lobbying.Footnote 129 Therefore, we controlled for additional variables. First, we controlled for accounting misstatement. We measured bystander firms’ accounting misstatements during the last three years before the Enron scandal. An accounting misstatement reflects accounting and auditing misconduct. We used the Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases (AAERs) data.Footnote 130 Second, we controlled for the same industry as Enron. We captured whether the firm was in the same industry as Enron or not. This is similar to the Team Jack variable in the Abramoff lobbying scandal case, as it demonstrates closeness to the culpability. Third, to capture the firms’ changed lobbying activities, we controlled for a change in lobbying expenditures (logged) from two time periods: (1) January 1998–June 2001 and (2) July 2001–June 2002. We calculated the differences between periods (2) and (1) to measure the change in lobbying expenditures.

Results

Tables B2 and B3 show the correlation matrices for Events 1 and 2. Given that we added changed lobbying expenditures in the Event 2 analysis, we added the changed lobbying expenditures in Table B3. We found that firms’ lobbying expenditures and changed lobbying expenditures show a negative correlation, which captured the firm's changed lobbying activities after the Enron scandal was debunked.

Table B4 provides the regression results for the admittance of wrongdoing on 8 November 2001. Model (1) only contains the control variables. Model (2) shows the negative responses from shareholders around the Enron scandal (β = –1.083; p = .033). Thus, H1 was supported. Model (3) contains the independent variable and moderator. Model (4) provides the results of the interaction effect of bystanders’ engagement in lobbying. We tested when the firm participated in lobbying, and whether shareholders showed more hostile responses to the bystander. We failed to see statistical significance (β = –.087; p = .302). Thus, H2 was not supported.

Table B5 shows the results of the regression table around the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Model (5) only contains the controls. In Model (6), bystanders that hired Arthur Andersen experienced more positive reactions from shareholders (β = 1.224; p = .085). Therefore, H3 was supported.Footnote 131 Model (7) contains the independent variable and moderator. Model (8) shows the effect of the interaction term. We found that firms engaging in lobbying enjoyed a more favorable response from their shareholders when the new regulation was introduced (β = .179; p = .087). Thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported. Figure B1 shows its interaction effect among firms.

Discussion

We capture the negative spillover by investigating the shareholders’ (of the bystanders) responses. We argue that the negative spillover among bystanders varies, depending on their associability with the wrongdoing. We also add the boundary condition of insufficient transparency, which levies a greater burden on shareholders for collecting firm information. However, when an objective intervention occurs, those bystander firms gain positive responses from their shareholders, as the intervention restores legitimacy to the tarnished behavior. Because the institutional remedy promises increased transparency, those firms experiencing transparency issues can enjoy more favorable responses from their shareholders. To investigate our arguments, we mainly leverage a corrupt lobbying scandal in 2006 and the subsequent new regulation (HLOGA) in 2007. Further, to secure generalizability, we introduce another example—the Enron scandal and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.

We contribute to the literature in three ways. First, we broaden categorization theory by demonstrating the replacement of a categorization setter around a wrongdoing. Taken-for-granted industry categories give way to an emerging category when they are associated with a wrongdoing. Specifically, we show that strategic behavior (which is the source of a wrongdoing) draws attention from shareholders and works as a category setter. When the wrongdoing is revealed, shareholders punish those firms that engaged in the culpable strategic behavior. This change in evaluation occurs because the taken-for-granted categories do not stand when new and significant information becomes available. At this time, we find that causal reasoning replaces taken-for-granted thinking.Footnote 132

Second, we illustrate that the level of negative spillover differs based on the degree of culpability. By highlighting the within-variance among firms that participated in the culpable strategic behavior, we show that shareholders’ suspicion regarding the firm's likelihood of engaging in the wrongdoing is associated with the level of the firm's activity in having engaged in the culpable behavior.

Lastly, we introduce the role of a credible third party in legitimacy restoration. The level of restoration from the reputational loss due to the firm's association with the wrongdoing is commensurate with how much legitimacy was lost. When the suspicion of the wrongdoing is resolved via credible third-party involvement, those firms that lost the most credibility are the ones that regain the most legitimacy. The level of legitimacy restoration around the enactment of the new law is based on the magnitude of the initial legitimacy loss.

Our research is not without limitations. First, we did not fully capture whether firms changed their nonmarket activities after the negative news about lobbying. Given a yearlong gap between the negative and positive news concerning lobbying, firms may have had enough time to reorganize their political activities, such as broadening their use of internal lobbyists or changing lobbying firms. Although we added the change in revolving-door lobbyists, lobbying expenditures, and PAC contributions, other features of the firms’ political activities may have changed, thereby affecting investors’ perceptions.

Second, it is possible that the firm could have changed its pattern of hiring revolving-door lobbyists. After firms experienced a negative response from shareholders and witnessed the stigma attached to having revolving-door lobbyists, firms might have had the incentive to modify how they could use their existing revolving-door lobbyists better. As a result, firms may have refrained from putting these lobbyists on the front line. If revolving-door lobbyists are the best at doing the frontline work, preventing them from doing their best might not be deemed a viable strategy from the standpoint of shareholders. This is related to the reason that Hypothesis 4 was not supported. H4 argues that the intervention of a third party will be of greater benefit to those firms that hire more revolving-door lobbyists. However, if the firms changed their usage tactics of lobbyists and other nonmarket strategies after the scandal, shareholders would have updated their views toward the firms. Thus, introducing the new law did not have a more powerful impact in terms of firms relying more on revolving-door lobbyists.

Lastly, we mainly focus on shareholders even though there are different types of stakeholders. Examining the shareholders’ responses through stock prices has been a well-established research area in management. As various shareholders could have unique views regarding lobbying, picking only one type of stakeholder could limit a fruitful discussion on using multiple stakeholders. As shareholders prioritize the market, they might regard lobbying differently than the general public. Additionally, even among shareholders, individuals, and institutional investors, and even among the institutional investors themselves, they could view lobbying through different lenses. Future research could compare different types of stakeholders with respect to lobbying and could separate shareholders into different groups based on their stances toward lobbying.

Conclusions

We find that a culpable firm's illegal lobbying reduces the legitimacy of bystanders that actively engage in lobbying. We also find that proper third-party remedies stemming from a credible third party can restore firms’ legitimacy. In addition, while firms that hired revolving-door lobbyists received the harshest punishment at the time of the culpable event of a focal firm, these firms also recovered their legitimacy the most when an institutional remedy was introduced.

Appendix A

Table A1. List of corrupt lobbying scandals in the United States and the United Kingdom.

Appendix B

Table B1. Variables of additional analysis of the Enron scandal.

Table B2. Descriptive statistics and pairwise correlation matrix, Enron scandal, Event 1. N = 192.

Table B3. Descriptive statistics and pairwise correlation matrix, Enron scandal, Event 2. N = 175.

Table B4. Regression Results, Enron scandal, Event 1. N = 192.

Table B5. Regression Results, Enron scandal, Event 2. N = 175.

Figure B1. Interaction effect of lobbying expenditures on the positive relationship between using Arthur Andersen and shareholders’ reactions to the introduction of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.