Introduction

In advanced economies, citizens express a growing distrust of political elites. At the same time, inequality has reached a level unseen since the beginning of the twentieth century.Footnote 1 Economists and political scientists broadly discuss this predicament. New studies link inequalities with, for example, support for radical populism and right-wing parties.Footnote 2 Furthermore, economists show that, particularly in Europe, the political conflict is organized chiefly along class lines.Footnote 3 Low-income and less educated voters support Euroskeptic political movements because they have no interest in further integration of the European Union.

A growing number of scholars argue that mitigating the damaging effects of inequality requires increasing taxes on top incomes.Footnote 4 Indeed, in recent decades both top income taxes and overall progressivity of tax systems were on a precipitous decline in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.Footnote 5 It is documented in the literature and might imply a welfare loss because lower taxes for the rich are not associated with concurrent higher economic growth.Footnote 6 Moreover, empirical evidence shows that lowering taxes for the affluent might increase economic inequality.Footnote 7

If the choice of the tax system has significant distributional implications, a crucial question arises—what conditions make governments follow progressive tax policies? This question is a subject of thorough inquiries in social sciences. We add to the existing literature by analyzing the specific case of the tax reform introduced in 2022 in Poland.

In May 2021, the Law and Justice ruling party proposed a reform, whose main political slogan was “making the tax system fair.”Footnote 8 It was aimed at lowering the taxation of low income and increasing the taxation of high income. The main reason behind the reform was an exceptional regressivity of the Polish tax system. Blanchet, Chancel, and Gethin estimate the ratio of the top 10 percent to bottom 50 percent effective tax rate in Poland to be 0.71, meaning that the top earners effectively pay lower taxes than the bottom half of the society. It is the fourth lowest ratio among the twenty-six European countries and the United States. One of the main reasons for the regressivity of the tax system in Poland is a little progressivity of income taxation.Footnote 9

The taxpayers to be most affected by the proposed reform were the self-employed with high incomes. The initial cost of the reform was fairly small (0.2 percent GDP), with high redistributive effects. However, the final overhaul—passed by the Parliament after four months of public consultations—had a significantly higher cost (0.7 percent GDP) and considerably lower redistributive effect. The changes introduced during the public consultation period were most beneficial for those who were supposed to be the most affected—self-employed reporting high incomes.

We analyze the public debate around the tax reform, which finally led to the diminution of negative effects of the reform on the wealthy. To this end, we use the novel theoretical framework for empirical analysis proposed by Babic et al.Footnote 10 The framework integrates working mechanisms of business power from the existing literature into one unified model. In this model, a clear distinction between structural and instrumental power is replaced by dyadic power relations between various actors. In other words, business power emerges as a complex phenomenon from the interplay of more straightforward forces (e.g., media campaigns or business lobbying).

Our analysis employs both qualitative and quantitative (text-mining) methods to investigate press articles on the tax reform published during the public consultation. Based on this, we show that although the reform was beneficial for most of the taxpayers, the discussion around it in the media had a predominately negative tone. The discourse was dominated by business associations, with very little activity of trade unions. In addition, negative media coverage was supported by a low level of public trust in the government. Both factors made it difficult for the ruling party to oppose the business narratives and convince voters, forcing the administration to cater to business interests and water down the reform.

Our article is organized as follows. The second section contains a literature review on the political economy of tax systems and the impact of business power on tax reforms. In the third section, we describe the details of the tax reform in Poland and the changes introduced during the public consultation period. In the fourth and fifth sections, we present the methods and data used, while in the sixth, we show the study results. Finally, in the conclusion section, we place our article in the literature, showing our empirical and methodological contribution.

Literature review

Democracy and redistribution

The understanding of redistributive politics and the relationship between democracy and inequality in economics as well as subdiscipline is still in an inchoate state. A classical argument from political economy and comparative politics results from the premise of median voter control and suggests that in a market democracy growing inequality should be spontaneously offset by stronger support for more progressive taxation. This reasoning was first outlined in the 1980s by Meltzer and Richard, who extended the research by Romer and Roberts.Footnote 11 Later, in the 2000s, several scholars elaborated on that theory.Footnote 12 The belief that democratic institutions lead to progressive taxation stems from the reasoning that democratic authorities respond to the demands and preferences of society to a greater extent than authoritarian governments. High economic inequalities should therefore change the preferences of the median voter and consequently, the policy outcomes.

However, this proposition has severe limitations. Firstly, empirical evidence shows the puzzling paradox of solid, unequal democracies that, nonetheless, have little or no redistribution, even if it is at odds with the median voter interests. Secondly, the research on political economy proposed several theories explaining why median voters do not have to support redistribution, despite the easily demonstrated profits it can bring them.Footnote 13 Finally, the research on political representation shows that interest of the median voter and policy outcomes might be divergent. For instance, politicians can use a variety of techniques to escape the penalty of decreased support by deceiving or bypassing voter preferences.Footnote 14

Considering the latest studies and state-of-the-art research, the consensus regarding progressive taxation and democracy is far from being established. In recent decades, many empirical studies using extensive datasets have been conducted. For instance, Acemoglu et al., through empirical investigation of panel data, demonstrate that democratization increases taxation as a fraction of GDP but does not influence the level of inequality.Footnote 15 Scheve and Stasavage show that during the last century, only war mobilization resulted in a considerable rise in tax progressivity. No political event (e.g., the establishment of universal suffrage) had a similar effect.Footnote 16 Limberg and Seelkopf came to very similar results on the historical roots of wealth taxes.Footnote 17 However, Seelkopf and Lierse, studying introductions of four central taxes from 1800 to 2015 in 131 countries, show that democracy plays a part in social development enabling the introduction of progressive taxes.Footnote 18

The absence of unequivocal findings in the research based on the median voter theory lends support to alternative theories, explaining the introduction of progressive taxation. Some scholars suggest that to rationalize variation in the level of taxation and redistribution in democracies, we should investigate economic elites rather than voters. Fairfield strongly supports this approach, building her research on Winters's studies on oligarchy, research on power resource theory in welfare state literature, and Hacker and Pierson's investigation into the so-called winners-take-all politics.Footnote 19 Affluence and economic resources, according to this viewpoint, are easily translated into political influence. Furthermore, the level of organization among economic elites, typically within the business environment, plays an important part in this process.

Conceptualization of business power

In the mainstream political science, scholars published many studies about business power. The first wave of interest in the subject took place from the mid-1950s till the 1980s, when it was discussed in the Marxist and radical pluralists circles.Footnote 20 The main drawback of Marxists' and radical pluralists' work was that it was only limited to theory and not subjected to empirical verification. Therefore, the supposed unique position of business was too immutable and absolute to be permanently accepted in the academic circles. As a result, it was quickly criticized by scholars like Vogel and ultimately abandoned in the 1980s.Footnote 21 Apart from a few exceptions, business power was largely ignored in mainstream political science circles in the next decade.Footnote 22

However, after years of lost academic standing, the intellectual inquiry on business power gained momentum again in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Many studies on the impact of financial institutions on states were conducted. For instance, Bell and Hindmoor empirically document how governments in the United States and the United Kingdom were forced by structural power embodied in the “systemic risk” to bail out banks during the financial crisis.Footnote 23 A similar study, with contrasting results though, was conducted by Culpepper and Reinke, who analyzed bank bailouts in four large economies. This study asserts that structural power can work in favor of banks only if they strongly rely on domestic markets and cannot threaten the government with moving headquarters abroad, which happened in Germany and the United Kingdom, but not in France and the United States.Footnote 24

Currently, two main research perspectives on business power dominate political science and subdisciplines.Footnote 25 First, instrumental approaches explore more direct, observable, and concrete power relations between actors and are based on methodological individualism. In this method, analyses may involve the purposeful acts of business actors intended to affect the state, such as lobbying, direct participation in governmental bodies, or political donations. Second, structural approaches use methodological holism and focus on indirect, unobservable, and abstract power relations. As a rule, studies employing this approach assume a form of structural dependency between the state and business. Moreover, structural approaches also entail discursive approaches, emphasizing the “power of ideas.”Footnote 26 By endorsing certain interpretations and excluding others, discursive power alters perceptions of actors and affects a policy-making process.

Recently, much has been done to integrate structural and instrumental approaches into one hybrid perspective. Although many authors have previously combined both powers in their analysis, to the best of our knowledge, Babic et al. were the first to call this a hybrid approach.Footnote 27 This integration attempt is motivated by the belief that the distinction between instrumental and structural power is artificial and should be replaced with the assumption of their interaction. Many scholars emphasize structural power as a signaling tool that establishes the rules of the political battle before it begins.Footnote 28 Furthermore, the outcome of the battle is determined by instrumental power. Before the beginning of a political process, some actors may be in a privileged position, but the success of implementing their objectives depends on their instrumental activity. Another strand of hybrid approaches stresses the importance of ideas and discourse.Footnote 29 According to this viewpoint, structural power is determined by the perceptions and preferences of political actors and the general public, which can be affected by a deliberate activity of business actors.

Business power in tax policy-making process

These theoretical foundations of research on business power form the basis of analyses concerning the impact of business on a tax policy-making process. In other words, the research on the impact of business power on tax changes describes a specific political process, but most often it looks at it through the conceptual lenses created in research on business power in general. Tax reforms are frequently examined at various stages of their implementation. From an early stage of agenda setting among policy makers, which is normally inaccessible to the public, to the consultation process in which various public interests determine political choices, until the final shape of the reform is established. Whereas other economic measures, such as trade liberalization or sectoral regulation, have vague distributional implications, progressive tax changes normally carry explicit costs for economic elites. As a result, despite a possible variation in attitudes and preferences, affluent actors usually resist changes threatening their income or wealth and, consequently, their overall social advantage. This resistance manifests itself through instrumental and structural power.

There are two main sources of instrumental power to be distinguished (Table 1). The first concerns the relationship between business and policy makers. For example, representatives of business organizations can influence the tax policy during public consultations, but also in a less visible way, through informal ties or partisan linkages. However, resources can also be a source of instrumental power. In this case, business can benefit from its cohesion, expertise, media access, and, of course, money. For instance, a preferential media access may serve economic elites in an indirect way by moulding public opinion. An extensive coverage of business viewpoints creates social exposure to narratives that favor certain interests. And this affects the views of both policy makers and voters.

Table 1. Sources of instrumental and structural power in tax policy making.

Source: Partly adapted from Fairfield (Reference Fairfield2015).

Structural power operates through less visible channels of influence, that is the perceptions of individual actors. On the one hand, policy makers can anticipate disinvestment potential and then leverage these concerns to support revisions to the proposed policy. Disinvestment potential can mean both the suspension of investments by companies, layoffs, and the risk of capital outflow abroad. On the other hand, business actors may use threats of divestment to influence public opinion and government officials. It should be emphasized that the structural power can hinder tax policy regardless of its actual effect, which cannot be known before the implementation.

Despite various available strategies for circumventing resistance, empirical evidence shows that establishing progressive taxation might be difficult in countries where economic elites possess both powers and additionally are well organized. Fairfield (Reference Fairfield2010) studies tax reforms in Latin America and shows that variation in instrumental power in Chile and Argentina explains different political outcomes.Footnote 30 Whereas in Chile, strong instrumental power eliminated progressive tax reforms from the political agenda, in Argentina, weaker instrumental power allowed for a significant increase in corporate tax. Bell and Hindmoor (Reference Bell and Hindmoor2014) demonstrate how the Australian government withdrew from introducing the Australian Mining Tax due to industry pressure.Footnote 31 The study shows that business, by shaping ideas, can convince the public opinion that tax hikes may cause disinvestment. Similarly, Babic et al. (Reference Babic, Huijzer, Garcia-Bernardo and Valeeva2022) evaluate the effects of structural power on the result of the dividend tax abolition in the Netherlands.Footnote 32 The study indicates that as long as there was a threat of industry exit, the Dutch government maintained the need to abolish the tax. However, once the threat had disappeared, the reform was promptly revoked.

Details of the tax reform in Poland

Motivation behind the reform and its initial shape

There were two main reasons for a little progressivity of the taxation of income in the Polish tax system before the tax reform was proposed. The first one was almost no progressivity in the tax wedge for employment contracts. The difference in the tax wedge between single workers earning 167 percent of the average wage and their counterparts earning 67 percent (the standard OECD measure of the tax wedge progressivity) equalled 1.3 pp. There was only one OECD country with a lower value in 2020 (Hungary). Low-income workers were particularly disadvantaged—the total compulsory payment wedge for single workers earning 67 percent of the average wage equaled 39 percent, well above the average in the OECD countries (34 percent).Footnote 33

The second was a relatively low taxation of the self-employed reporting high incomes. According to the Ministry of Finance data based on tax returns, the average effective taxation (including social security contributions and allowances) of the high-income self-employed (with incomes 2–4 times the average annual income) equaled 26 percent in 2017. It was almost one-third lower than that of similar workers on employment contracts (37 percent).Footnote 34 This was the reason for the spread of fictitious self-employment among high-income workers. It is thought to refer to almost 170,000 self-employed—every tenth business in Poland.Footnote 35

These problems have been pointed out many times by experts and international organizations. For example, the OECD Economic Surveys for Poland repeatedly indicated that there is room for comprehensive income tax and social security contributions (SSCs) reform aimed at boosting the employment of low-skilled workers, strengthening social cohesion, and increasing tax compliance.Footnote 36

On 15 May 2021, the Law and Justice ruling party, presented the “Polish Deal”—a plan of reforms for the recovery from the pandemic crisis. One of the main elements was a comprehensive reform of income taxation, considered to be a response to the aforementioned challenges. It included the following actions:

• Introduction of a tax-free amount of PLN 30,000 a year;

• Increase of the second income tax bracket of 32 percent—from PLN 85,000 to 120,000 a year;

• Elimination of the health insurance contribution tax deduction (before the reform, most of the contribution of 9 percent was deductible from tax liability);

• Replacement of lump-sum health insurance contribution for self-employed by a proportional contribution of 9 percent; and

• Introduction of a middle-class tax relief for workers on employment contracts. It applied to selected taxpayers who earned between PLN 5 701 to PLN 11 141 (approximately from 100 to 200 percent of the average wage).

Thus, the reform plan covered a wide range of instruments. Altogether they were to be beneficial for most taxpayers—68 percent of workers on employment contracts, 39 percent of self-employed, and 91 percent of pensioners (by the primary source of income), and unfavorable for 12, 60, and 5 percent, respectively (neutral for the rest).Footnote 37 The lower the income, the benefits were to be the bigger. In the case of workers on employment contracts, the reform plan lowered the tax wedge for earnings lower than the average wage, remained the same for income ranging from 100 to 230 percent of the average wage and increased the tax wedge for higher earnings. In the case of self-employed, the cross-point equaled around 120 percent of the average wage—the reform was expected to decrease the tax wedge for lower earnings and increase for higher earnings. Also pensioners—most of whom have a relatively low income—were among the reform biggest beneficiaries.

The opportunities for political use of the reform seemed to be significant. The estimated number of reform beneficiaries was much larger than the number of those to lose—the numbers equaled 17.8 m and 2.7 m, respectively. The reform was supposed to have significant redistributive effects. The cumulated gains of the bottom nine deciles were presumed to be PLN 24 bn (1 percent of GDP), and the losses of the single tenth decile were to be PLN 19 bn (0.8 percent of GDP). The total fiscal balance of the reform was only slightly negative—it amounted to about PLN 5 bn (0.2 percent of GDP).Footnote 38

The final shape of the reform

The tax reform dominated the politics in Poland in the summer of 2021. The project of the legal act introducing the changes was published on 26 July, submitted to the Parliament on 8 September, and passed by the Sejm (lower house of the Polish parliament) on 1 October. In this period, which we later refer to as public consultation,Footnote 39 three critical adjustments to the initial reform plan were put in place:

• Reduction in the rate for the simplified settlement method for self-employed representing IT (from 15 to 12 percent) and the healthcare sector (from 17 to 14 percent);

• Introduction of a preferential health insurance contribution of 4.9 percent for self-employed paying a flat income tax; and

• Inclusion of the self-employed in the tax relief for the middle class.

These three changes were neutral from the perspective of workers on employment contracts and pensioners. The beneficiaries were self-employed, mainly those with relatively high incomes. The extension of the middle-class tax relief lowers the tax wedge for the self-employed with income ranging from around 100 to 200 percent of the average wage, while the preferential health insurance contribution benefits the income higher than 200 percent of the average wage. Also, IT specialists and medical professionals on self-employment (mainly doctors and dentists) usually achieve relatively high incomes.

As a result, changes significantly lowered the redistributive effect of the reform and increased its fiscal cost. While the changes had little effect on the average benefit in the first nine deciles, the average loss of the tenth decile households has dropped by almost half. The total cost of the reform increased by PLN 12 bn (0.5 percent of GDP)—to a large extent, benefiting top earners (in comparison to the initial shape of the reform).Footnote 40

Moreover, the changes in the reform introduced during the public consultation period kept the prereform motivation for fictitious self-employment. The initial version of the reform was supposed to lower the difference between the tax wedges for a worker on an employment contract and a self-employed—both earning three times the average wage—from 20 to 14 pp. The final version brought that level almost entirely back—to 18 pp.

Figures 1 and 2 sum up the tax wedges before, during and after the reform and their redistributive effects in the initial and final versions.

Figure 1. The tax wedges before, during and after the reform.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Figure 2. The redistributive effects of the initial and final tax reform.

Source: Myck et al. (Reference Myck, Oczkowska and Trzciński2021).

The reform was further watered-down in 2022, when the income tax rate in the first bracket was reduced to 12 percent, a special deduction of health contribution for some self-employed was introduced and the middle-class tax relief was abolished. This roughly doubled the total cost of the reform. The changes introduced in 2022 are beyond the scope of this article; however, they were also affected by the mechanisms described in the following sections.

The research method

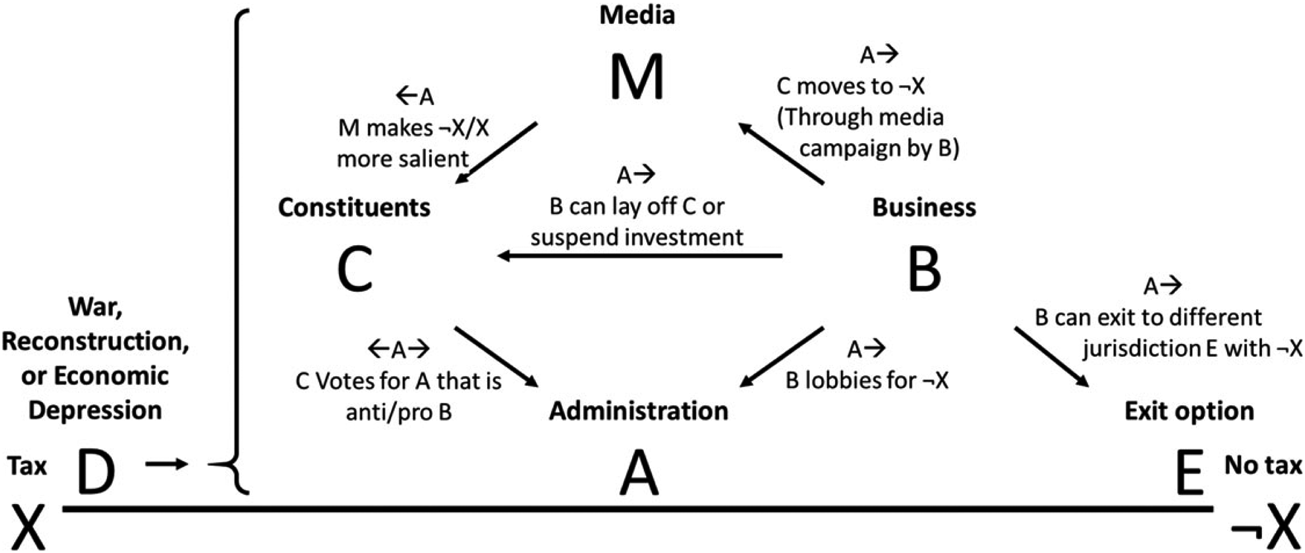

We apply the framework proposed by Babic et al. (Reference Babic, Huijzer, Garcia-Bernardo and Valeeva2022) to extract the operating mechanisms of business power from the media debate around the reform. The essence of the framework is presented in Figure 3. It is the so-called hybrid approach comprising instrumental and structural power analyses. As the authors indicate, in this conceptualization, “the structural power stems from the perceived availability of various dyadic instrumental capacities on behalf of business.” In this framework, perceptions play a crucial role in the dynamics of business power. In addition, the framework arises from the observation that businesses would probably have little leverage from direct instrumental power without indirect mechanisms: the credibility to fire workers, move abroad or influence the media.Footnote 41

Figure 3. The framework for analysing the working mechanisms of business power.

Source: Babic et al. (Reference Babic, Huijzer, Garcia-Bernardo and Valeeva2022).

We build upon this framework, trying to catch the main mechanisms of shaping perceptions in the media articles and experts' comments on the tax reform in Poland: how the business power influenced constituents’ perception of the proposed reform through media (B→M→C), how it directly threatened constituents with potential layoffs, suspended investment (B→C) or exit to another country (B→E), and how external factors, such as a war or a pandemic, were pronounced in the decision-making process (D).

We perform both qualitative and quantitative analysis on the dataset of press articles concerning the tax reform published during the public consultation process (see “The Dataset” section for details). We divide the analysis into five steps:

1. We report the number of instances the external experts expressed their views in the media to show how significant was the involvement of different groups in the public debate around the reform.

2. We perform a sentiment analysis of the comments provided by external experts and a sentiment analysis of the journalists’ texts (the texts in which the journalist does not use external comments). The sentiment analysis is performed in two ways. First, by using the R programming language package called sentimentr. It is a sentiment analysis package based on a dictionary look-up approach that combines weighting for valence shifters (negation and amplifiers). It is designed to provide a better accuracy than a simple dictionary look-up, while displaying fast processing times. Sentimentr allows to calculate an average sentiment of the whole paragraph or article by averaging the sentiment values of individual sentences. The positive words are assigned a value of 1 and negative words a value of –1. However, the averaging of sentences’ scores, combined with the weightings for valence shifters, the additional negative values up-weighting and zero values down-weighting, impedes defining the obtainable sentiment value range. The negative values indicate negative sentiment, and positive values—represent a positive sentiment. To use the sentimentr package, which operates on the English lexicon, all the texts have been translated from Polish into English using the cloud-based Google Translate software. Second, each comment and article are subjectively assessed by the authors as displaying either a positive, neutral, or negative sentiment. The texts with positive sentiments are then assigned a value of 1; neutral sentiment is assigned 0 and negative sentiment is assigned –1. This is performed for two reasons: (a) to provide the sanity check to the results of the sentimentr usage and (b) to obtain results for the groups for which the sample of comments is too low to effectively use a dictionary look-up method (more details in the “Results” section).

3. We qualitatively draw the main narratives using the comments of external experts by investigating each comment and classifying them into groups of similar narratives.

4. We analyze the public opinion surveys about the tax reform carried out during the public consultation process to look at the voters' perception of the debate on the reform.

5. We analyze the process of developing amendments to the reform, which significantly reduced its redistributive effect, including the arguments politicians used to prove the changes.

We divide the actors engaged in the debate on the reform into five groups, according to their affiliation. We start by distinguishing three groups traditionally involved in social dialogue—employer organizations, trade unions, and public administration. Then we add the so-called third sector—nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and higher education institutions. Finally we gather other business representatives, not affiliated with an employer organization, in a group which we call “advisory services and the banking sector” (as the experts from tax advisory companies and banks are the dominant part of the group). In the following text we describe these groups in detail, in the order that appears later in the results section.

The first group of actors is the representatives of advisory services and the banking sector. These experts are often invited to comment on technical issues related to taxation and the macroeconomic impact of the reform. They usually represent large entities—multinational advisory companies or banks (largely state-owned). Ex ante, their attitude to the reform is not apparent. The second is representatives of employer organizations. This group consists of business lobbying associations, directly interested in overthrowing or considerably modifying the reform that hit primarily their members. The five most influential associations in Poland are the Business Centre Club, Confederation Lewiatan, Employers of Poland, Federation of Polish Entrepreneurs, and Union of Entrepreneurs and Employers. When considering the business power usage later in the analysis, we concentrate mainly on the activity of this group of actors. In Poland, such associations to a large extent represent the interests of small and medium enterprises. It is consistent with the features of the analyzed tax reform, as the reform applied to large companies to a relatively small extent (large companies are usually CIT payers, while the reform concerned primarily changes in PIT and health contribution). The third group is formed by the representatives of NGOs and higher education institutions—mainly experts from think-tanks and universities. We consider them as expressing independent opinions toward the reform, with the proviso that a relatively strong position in the public debate is held by think-tanks funded by business (especially the Civil Development Forum). The fourth group of actors is the representatives of public institutions, especially ministries and public think-tanks (e.g., Polish Economic Institute). From definition their attitude to the reform is expected to be positive. Finally, the last group is formed by the representatives of trade unions. As most of the benefits of the reform goes to employees at the expense of entrepreneurs, therefore, ex ante, one may assume a positive stance to the reform of this group of actors. However, as can be seen later in the analysis, their position in the public debate is relatively weak.

The dataset

We compile a dataset of press articles concerning the tax reform published between 15 May 2021 and 1 October 2021, that is between the day of the announcement of the “Polish Deal” and the day when the final legal act including amendments in favor of the high-income self-employed was passed by the Sejm. We consider articles from the three most opinion-forming Polish newspapers: Rzeczpospolita, Gazeta Wyborcza, and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna—as ranked by the Institute of Media Monitoring for 2021. The ranking is based on the number of citations of articles/statements of one medium used by other media. Therefore, the three newspapers can be considered as having the greatest impact on the public discourse.Footnote 42

We study the electronic versions of the paper editions and include in the dataset all the articles that have anything to do with the tax reform. Additionally, we have separately distilled all the comments of external experts used in the articles—usually short (1–5 sentences) statements. The initial dataset consisted of 359 articles and 378 comments. Then, we divided all the articles and comments into two groups: general and technical. The first group concerns the core idea of the reform—the number of beneficiaries and those to lose in the reform, the redistributive effects and the macroeconomic and fiscal consequences. The second group deals with issues related, for example, to the tax settlement manners and deadlines, the interaction of the reform with the pension system or the financial condition of the local governments. In our further analysis, we use only the general articles and comments, as we aim to study the perceptions of the redistributive idea behind the reform rather than technical solutions. As a result, our final dataset consists of 156 articles and 207 comments. We classify all the comments by the experts’ affiliation according to the division we made in the previous section. Due to copyright issues, we cannot make our dataset publicly available. Instead, we share a complete list of articles included in the dataset for potential replication or further use.Footnote 43

Results

How has business influenced media? (B → M)

Business representatives dominated the debate around tax reform throughout the public consultation period. Experts representing employer organizations provided over 40 percent of all comments in the analyzed media. Together with advisory and banking sector representatives, businesses covered approximately 75 percent of all comments (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Number of comments by experts’ affiliation.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

The most striking observation is the discrepancy between the employer organizations and trade union presence in the media. The nature of the reform should raise a dispute between these two groups, as, to a large extent, the reform focused on redistribution from well-paid businesses to low-paid employees (as indicated in “Details of the Tax Reform in Poland” section). However, Poland has one of the weakest systems of workers' bargaining in the European Union, with a low level of trade union coverage, especially in the private sector.Footnote 44 The weakness of this system is also visible in the media debate—the trade union representatives were hardly present in the debate on tax reform, providing only 5 out of 208 comments in the analyzed media the during public consultation period. As a result, the advantage of business representatives in the media was overwhelming.

As expected, the sentiment of the comments of the employer organizations’ representatives was strongly negative. In the five selected groups, experts from employer organizations had the most negative sentiment—both in the subjective and objective (dictionary look-up) analyses (Figure 5). On average, the advisory and banking sector as well as NGOs and the higher education sector also had a negative sentiment. However, in the last case, the sentiment was closer to neutral, especially in the objective analysis. The sentiment of public institutions and trade union representatives was positive (as expected), but their share in the total number of comments was marginal and, therefore, probably had a low impact on the general outlook of the reform in the media. It is worth noting that, generally, the sentiments obtained by the dictionary-based method are similar to the sentiments obtained by the subjectively labeled data.

Figure 5. The sentiment of comments by experts’ affiliation—subjective analysis and dictionary look-up.

Note: the public institutions and trade unions are not included in the dictionary look-up due to the insufficient number of comments provided for a reliable analysis (see Figure 4).

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

Business representatives' high involvement affected the way journalists presented the reform. There are two arguments in favor of this hypothesis. First—over time, the sentiment of journalists became similar to that of employer organizations’ representatives. At the beginning of the public consultation—after the initial presentation of the reform—the sentiment of the journalists was close to neutral. However, with the ongoing debate, the negative sentiment among journalists was growing steadily, finally becoming on a par with the negative sentiment of employer organizations' experts (this observation results from both subjective and objective analyses; see Figure 6). Second, there are multiple examples of the narratives of business representatives included in the titles of the articles, for example “This is not the time for higher taxes for entrepreneurs,” “Business: the government does not play fair with us,” and “There is no consent to a drastic increase in taxes for companies.”Footnote 45 Overall, around one-fifth of all articles in our database comprise a business threat in the title or the headline (see more about business narratives in the following subsection).

Figure 6. Evolution of the sentiment of employer organizations’ representatives and journalists—subjective analysis and dictionary look-up.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

What narratives did business use? (D; E; B → C)

We identify four main narratives used by the business to threaten public opinion and influence tax reform. In the following text we present the narratives with the examples of comments included in the articles.

Economic deterioration (B → C): Higher taxes for well-paid businesses mean slower growth, loss of competitiveness, lower investments, and layoffs. This narrative is also related to other arguments used (described in subsequent two narratives)—higher taxes for those who are better-off hit the “most productive” part of the economy and may cause an exodus of specialists. Examples:

The project would make sense if it supported investment through investment incentives for entrepreneurs. To achieve that, you cannot take their money away. You should leave it. Footnote 46

[The reform] is purely distributive, not developmental. Footnote 47

Polish small and medium enterprises react with withdrawal, low investments and slower development. In the long run, it does not help in building the potential of the economy. Footnote 48

On the one hand, the government focuses on economic growth and investments, including attracting foreign investors. On the other hand, it sharply increases the fiscal burden. In our opinion, these are two opposite strategies that cannot coexist. In this situation, it is hard for entrepreneurs to plan business development. Footnote 49

Penalty for resourcefulness (B → C): Progressive taxes hit those who contribute the most to the economy and lower the incentives for personal development. This argument may be particularly persuasive in a postcommunist, fast-growing, catching-up economy like Poland. Voters may be against higher taxes for the better-off because they hope to become better-off in the future. Examples:

After all, it cannot be that the enormous financial transfers for the needy take place mainly at the expense of the most productive people. Footnote 50

More significant redistribution of income from higher earners to lower earners will discourage citizens from being more active and weaken competitiveness. Footnote 51

Increasing the labor costs of the most qualified workers creates further wage pressure and reduces the competitiveness of enterprises responsible for innovation, which we need so much. We understand helping the poorest, but these proposals show that when it comes to taxes, we prefer working-class jobs at the expense of those with high value-added. It may also discourage investors. Footnote 52

High earners will bear the cost of the reform.… It can be called punishment for too high earnings. Footnote 53

Exit option (E): Companies/high-qualified specialists will move to another tax jurisdiction. In this respect, three countries were mentioned in the debate as the potential destinations for tax avoidance: Cyprus, the Czech Republic, and Estonia. Examples:

The unfavorable situation for entrepreneurs and the self-employed may lead them to look for better conditions in other countries. Footnote 54

It is about the fate of 700,000 entrepreneurs on flat PIT that can relocate their shared service centres abroad. Footnote 55

The rise in taxation of people with higher earnings, either employed under an employment contract or self-employed, is disturbing. In the best case scenario, it may cause wage pressure, while in the worst case scenario—the escape of the best specialists abroad. Footnote 56

Announced changes may very effectively lead to pushing out of the Polish market tens of thousands of IT specialists. Footnote 57

Despite many tax facilitations for Cypriot companies being lifted a couple of years ago, there is still a way to establish a company with minimal formalities. It is worth noting that there is no minimum share capital in Cyprus, and there is no obligation to cover it. Footnote 58

Some Polish clients mention Polish Deal as a reason for setting up companies in the Czech Republic. Footnote 59

Wrong timing (D): A crisis and a recovery are not good times for a large-scale tax reform. The business used the circumstances related to the COVID-19 crisis to evoke a sense of threat. In this reasoning, the tax reform will deepen the uncertainty and hinder investments needed for recovery. Interestingly, the ruling party used the same reasoning to present the package of reforms (including the tax reform) as the idea of a new, fairer economic system for a new time. Examples:

Recovering from the pandemic, we face chaos instead of order. In addition to the external uncertainty that is the pandemic, we also deal with uncertainty created by the government. Footnote 60

After more than a year of a pandemic, the situation of many entrepreneurs is tough. This is not the time for increasing burdens.… The government should not bother with it now. Footnote 61

We raise the burdens in a situation of considerable uncertainty related to the pandemic and its economic consequences. Footnote 62

The pandemic is the worst time for raising taxes. Footnote 63

How does the debate confuse voters? (M/B → C)

Despite the estimated number of beneficiaries of the reform significantly exceeding the estimated number of those to lose (17.8 m and 2.7 m, respectively; see “Motivation behind the Reform and Its Initial Shape” section), most of the public expressed a feeling that they would suffer from the reform. According to the survey conducted in mid-June (around four weeks after the initial presentation of the reform) on a representative sample of Polish adults, only 23 percent of respondents agreed that they would benefit or rather benefit from the reform. The percentage was lower than the percentage of respondents indicating that they would lose or rather lose in the reform (30 percent) (Figure 7). Similar results were obtained in surveys carried out in early August (2.5 months after the presentation of the reform) and in the first half of September (close to the end of the public consultation). In each of them, the share of respondents who believed they would not benefit from the reform (either lose or stay neutral) significantly outstripped the respondents agreeing that they would be in the beneficiaries group.Footnote 64

Figure 7. The discrepancy between public feeling about the reform and the estimated share of beneficiaries and those to lose in the reform.

*The survey was carried out from 7 to 17 June 2021 on a sample of 1,218 people—representative of the adult population of Poland (including 60.8 percent—CAPI method, 26.7 percent—CATI, and 12.6 percent—CAWI). The question asked: “Do you expect to benefit or lose from the announced tax changes personally?” The question was asked only to people who had heard about the reform.

The discrepancy between the official estimations and the expectations of the taxpayers about the reform may be explained by at least two factors. One is the indolence of the ruling party in signaling the main idea and potential benefits of the reform to the general public. The other is a strongly negative and worsening sentiment regarding the reform in the media, driven by business representatives actively incorporating their narratives in the public discourse. Both factors worked as mutually supportive components. In addition, the general mechanism was probably strengthened by a shallow trust in the government in Poland. Just 27 percent of respondents in Poland have confidence in their national government—the second lowest share among the OECD countries.Footnote 65 This disbelief is driven rather by a low level of general trust in politicians than a low level of trust in a specific party, as the ruling party still leads in most of the election polls. Furthermore, the low level of trust helps explain why the ruling party's effort to oppose negative opinions about the tax reform was met with confusion rather than reinforced support among many voters. The bewilderment can be seen in the previously mentioned survey. About 15 percent of all respondents declared that they did not know whether they benefit from the reform.

How did the business interests infect politicians? (B/C → A)

The tensions around the reform led to the introduction of business-friendly amendments to the final bill. In the case of each of the three changes described in “The Final Shape of the Reform” section, the rationale for them was to reduce social resistance against the reform and increase the business support, which was directly communicated by the politicians. As an example, we describe the process of developing the preferential health insurance contribution of 4.9 percent for self-employed paying the flat income tax. This is the most important out of the changes introduced during the public consultation, in terms of both: (a) the fiscal cost (around PLN 5 bn, i.e. 0.2 percent of GDP) and (b) watering-down the redistributive effect (all the benefits went to self-employed with high income—at least twice the average wage).

The information that the government considered introducing a preferential health contribution for the self-employed first appeared in the middle of August 2021—after three months of heated public debate on the reform. The media reported that the politicians think of the solutions to ease the negative perception of the reform among voters and business representatives.Footnote 66 The leaks were confirmed in the first week of September, just before the project of the legal act introducing the reform was submitted to the Parliament. Again, the indicated aim was to “reduce the resistance to the reform,” mainly from the business representatives, but also from the business-friendly MPs of the ruling coalition (as reported by a usually well-informed journalist).Footnote 67 The preference for the business was justified as a compromise. “The health contribution rate … after many talks with business representatives, including the small and medium enterprise spokesman, was reduced by almost a half, to 4,9 percent. This is a healthy compromise”—argued Jan Sarnowski, deputy finance minister responsible for introduction of the reform.Footnote 68

As reported by the media, in the period between the emergence of the idea of a special relief for the business and its announcement, closed-door negotiations were held between the government and business representatives. They were attended by a mediator—Bartłomiej Wróblewski, the Head of the parliamentary Special Committee for Deregulation.Footnote 69 “It was about finding solutions acceptable to both sides, so that the most important features of the Polish Deal could be implemented, … and at the same time to limit the increase in the burden on small and large companies”—Wróblewski said after the preferential health insurance contribution was announced.Footnote 70

This example shows that the business used both the instrumental and structural power to water-down the tax reform—as distinguished by the traditional approach to business power analysis. However, the key role was played by creating negative perceptions on the reform. The public pressure left a strong mark on politicians, who had to react to restore the image of the reform and save the chances of its adoption.

Conclusion

The case of the tax reform in Poland accurately illustrates how business power can indirectly influence policy outcomes. The tax reform, initially proposed by the ruling party in May 2021, aimed at reducing the tax burden for low-income taxpayers and increasing the tax burden for high-income taxpayers, primarily the self-employed. However, throughout the public consultations, the reform was gradually watered-down. The government made significant concessions to business associations and finally substantially reduced the progressivity of the reform.

Our analysis demonstrates that business representatives dominated the debate around the tax reform, covering three out of four comments in the media. Furthermore, the sentiment of business representatives' comments was, on average, more negative compared to other groups. We also find out that over time initially slightly negative sentiment of journalists was gradually decreasing and converging with the strongly negative sentiment of business representatives. This finding suggests that business could have effectively influenced the general stance of the media regarding the reform. The debate confused the public opinion, creating among many voters a false belief that they will suffer from the reform. Finally, the government introduced business-friendly amendments to the final bill and admitted that the main aim of the changes was to increase business support and reduce social resistance against the reform.

Our contribution to the literature is twofold. The first is empirical. We provide evidence of how business power can sabotage unfavorable reforms—similar to some of the studies we mention in the literature review section. In our case study, business power is exercised under unique conditions: in a postcommunist country with weak trade unions as well as little trust in government. A similar background of tax reform introduction was examined in Fairfield's research on Latin America, although the use of business power in Eastern Europe seems to be understudied.Footnote 71 In this context, we strongly emphasize the key role of creating perceptions in building the environment for or against specific regulations. We complete to Shiller's work, which identifies “stories” as the fundamental driver of many economic events, as well as Bell's work, which reveals how ideational processes adopted by different government officials mediate structural power.Footnote 72 We document some well-known narratives used by business representatives to oppose redistribution and progressive taxation. First, the argument about economic deterioration, which suggests that increasing taxes for high earners will thwart economic progress (e.g., cause lower investments and layoffs). This narrative is prevalent in political science literature and can be interpreted as a manifestation of the structural power of the business.Footnote 73 Second, the reasoning emphasizing that high taxes are a penalty for resourcefulness. This argument is especially interesting in a middle-income country such as Poland, where many people are still financially catching up. Therefore, we might expect that preference for redistribution is, to some extent, determined by the prospect of upward mobility.Footnote 74

The second contribution is methodological. To our best knowledge, our article is the first application of the unified framework proposed by Babic et al.Footnote 75 We show how the method may be used in explaining business power mechanisms and that it has the potential to become a valuable tool for researchers. Moreover, we improve the proposed framework by adding a quantitative element—the sentiment analysis of the media coverage. The analyses of business power usually need a careful qualitative element—this is what we do in a large part of our article. However, we believe that adding a quantitative input gives additional reliability to the results obtained.

Conflict of interest

None.